Abstract

Purpose

There are only limited data on drug utilization patterns in pediatric inpatients, especially on general wards. The aim of the study was to describe prescribing patterns and their associations with prescribing errors in a university children’s hospital in the German-speaking part of Switzerland.

Method

This was a subanalysis of a retrospective single-center observational study. Patient characteristics and drug use of 489 patients with 2693 drug prescriptions were associated with prescribing errors. Drugs were categorized by the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC), patients were categorized by age group according to European Medicines Agency guidelines, and prescribing errors were analyzed by type [Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification] and severity of error [adapted National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting (NCC MERP) index].

Results

The most frequently prescribed ATC classes were nervous system (N) (42.6%), alimentary system (A) (15.6%), and anti-infective drugs (J) (10.7%). Eighty-two percent of patients were prescribed an analgesic. Most drugs were prescribed for oral (47%) or intravenous (32%) administration, but the rectal route was also frequent (10%). The most frequently prescribed drugs were paracetamol, metamizole, and ibuprofen. The high number of metamizole prescriptions (37% of patients were prescribed metamizole) is typical for German-speaking countries. Older pediatric patients were prescribed more drugs than younger patients. A statistically significant difference was found in the rate of potentially harmful errors across age groups and for gender; children between 2 and 11 years had a higher rate of potentially harmful errors than infants under 2 years (p = 0.029) and female patients had a higher rate of potentially harmful errors than male patients (p = 0.023). Recurring errors were encountered with certain drugs (nalbuphine, cefazolin).

Conclusions

Our study provides insight into prescribing patterns on pediatric general wards in a university children’s hospital in Switzerland and highlights some areas for future research. Especially, the higher risk for prescribing errors among female pediatric patients needs further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This article gives an insight into prescribing patterns on pediatric general wards in a university children’s hospital in Switzerland and the properties of the prescribed drugs as well as the association of the prescriptions with patient age and gender. |

The top 20 most prescribed drugs are identified in different age groups. |

Prescribing errors associated with certain drugs or patients are described, to focus on in future research. |

1 Introduction

“Medication without harm” is still in the Global Safety Action Plan 2021–2030 of the World Health Organization [1]. It is known that children bear a higher risk for medication errors and especially prescribing errors [2,3,4]. The basis for any initiative to improve medication safety in a population is knowing their drug utilization. In pediatric inpatients, there is only limited data available on drug utilization [5]. Most pediatric studies focus on newborn patients [6,7,8,9], on pediatric outpatients [10], or on certain medications such as antimicrobial drugs [11], analgesics [12, 13], or antiepileptics [14].

On pediatric general wards, Rashed et al. [15] investigated drug utilization in five countries in different areas of the world and found that older patients (aged between 11 and 18 years) were prescribed more drugs than younger patients. The most frequently prescribed therapeutic groups in countries comparable to Switzerland such as Germany, the UK, or Australia were systemic anti-infectives, drugs for the nervous system and alimentary tract, and metabolism drugs, with the most frequent active ingredients being paracetamol, ibuprofen, and salbutamol.

In Austria, a neighboring country of Switzerland, Rauch et al. [16] investigated prescribing patterns in pediatric hospital care, where drug dispensing data from the hospital pharmacies was obtained. They found amoxicillin/beta-lactamase inhibitor, ibuprofen, and paracetamol to be the most frequently prescribed compounds.

In the French-speaking part of Switzerland, a study by Di Paolo et al. [17] on pediatric outpatients of the University Hospital Lausanne in 2005 and 2010 showed the most frequently prescribed 15 drugs accounted for 80% of all prescriptions, with ibuprofen and paracetamol being the most frequently prescribed. Recently, Tilen et al. [18] compiled a list of the 40 most frequently used drugs in pediatrics in Switzerland, based on drug consumption data from the hospital pharmacies for the compilation of nationwide harmonized drug dosage recommendations. They did not rank the drugs according to the frequency of usage.

2 Aim

To date, there are no data available on drug prescribing patterns on pediatric general wards in Switzerland, and only scarce data from Europe in general. Therefore, we aimed to provide insight on what drugs are prescribed in daily practice on pediatric general wards at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich and explore the characteristics of the drugs.

As prescribing errors are a major safety problem in pediatric patients, we also aimed to explore the types of errors that occur in association with the prescribed drugs and the characteristics of the patients to potentially find recurring errors that could be avoided in the future.

3 Materials and Methods

We conducted a subanalysis of a database compiled for a retrospective single-center observational study, which was published in March 2023 [19].

3.1 Patient Data

The database and the methods used to obtain these data are described in detail in a previous publication [19] of the same authors. The most important key points of our subset of data are as follows: we assessed the drug prescriptions of 500 patients (age 0–18 years) hospitalized at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich on six pediatric general wards (surgical and medical wards) between October and December 2019. The University Children’s Hospital Zurich is a tertiary care center. Drugs were prescribed by using a computerized physician order entry (CPOE) with limited clinical decision support including drug–drug interactions and check for duplicates. All prescriptions issued within the first 24 h of admission were recorded except for the following: parenteral nutrition, lipids, any blood cell transfusions, insulin, solutions for dialysis, solutions for fluid management such as normal saline solution, dextrose 5% in normal saline solution, dextrose 5%, or acetated Ringers. Only patients with at least one drug prescription were eligible for the study.

Patients were categorized into four age groups according to the European Medicines Agency guidelines [20]. As there were no preterm patients in our population, a preterm category was not included.

-

Newborn (term newborn infants): 0–27 days

-

Infants (infants and toddlers): 28 days to 23 months

-

Children: 2–11 years

-

Adolescents: 12–18 years.

3.2 ATC Classification

The anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system classifies the active ingredients of drugs in different levels [21]. Of all drugs prescribed, the name of the active ingredient, the trade name, and the related ATC code was recorded. ATC level 1 (anatomical/pharmacological group), ATC level 2 (pharmacological/therapeutic group), and ATC level 5 (chemical substance) were evaluated as outcomes.

3.3 Prescribing Errors

All prescriptions were checked by a pharmacist on prescribing errors and classified according to the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification v9.1, German Version [22, 23] into different types of errors. Dosing errors were assessed according to a manual presented in Supplement 1. The severity of harm was rated according to the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting (NCC MERP) index in the adapted version by Forrey et al. [24,25,26], with categories A = capacity to cause error, B = does not reach patient, C + D = no harm, E + F + H = temporary harm, G = permanent harm, and I = death. Error rates were calculated as overall error rates (NCC MERP severity A–I) and as potentially harmful error (PHE) rates for NCC MERP severity E–I.

Five percent of prescriptions were validated by a second pharmacist, and interrater reliability was calculated (see previous publication [19]).

3.4 Database and Statistical Analysis

The study database was built with Microsoft SQL Server 2019 Master Data Services. Evaluation and visualization of the anonymized data was carried out with Microsoft Power BI Desktop, and statistical analyses were conducted with RStudio 2022.02.1 and IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 27.

We intended to perform logistic regression to find factors that influence whether a prescription contains an error or not. We tested the following predictors: route of administration (ROA), ward, and age of patients. We found only models that, although significant, showed an effect < 0.1 (R2). Therefore, we decided to only analyze the data descriptively and to not use logistic regression. The number of prescriptions or number of errors were compared by t-test or one-sided ANOVA.

4 Results

Five hundred patients were randomly selected from 1608 eligible patients (see Fig. 1). Of these patients, 11 were neonates, 167 were infants, 222 were children, and 100 were adolescents. The number of newborns was very low as most patients at this age stay on the neonatal intensive care unit rather than on pediatric general wards. For this reason, we did not consider the sample to be representative and excluded newborns from the study.

Of the remaining 489 patients (Fig. 1), 210 were female and 279 male. The mean age was 6.2 ± 5.4 years, mean weight was 24.1 ± 19 kg, and mean height was 113.2 ± 38 cm. The patients stayed for a mean of 2.5 days and had on average 3.4 diagnoses.

4.1 Drugs Prescribed by Anatomical Class and Therapeutic Group (ATC Levels 1 and 2)

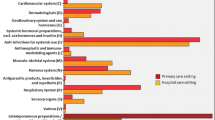

A total of 2693 prescriptions were analyzed. Table 1 shows that drugs for the nervous system (N) were prescribed most often, followed by drugs for the alimentary system (A), anti-infectives (J), and drugs for the musculoskeletal system (M). More than three-quarters (77.8%) of all prescriptions contained one active ingredient of these four main ATC classes. 423 patients received at least one drug for the nervous system (N), resulting in a proportion of 86.5% of patients.

Table 1 displays that analgesics (N02) and antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products (M01), which include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), accounted for 41.4% of all prescriptions.

Analgesics such as metamizole, nalbuphine, and paracetamol (N02) were prescribed to 400 patients (81.8%). Antiinflammatory and antirheumatic products such as ibuprofen and diclofenac (M01) were prescribed to 187 patients (38.2%). Antibacterials for systemic use such as amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefazoline, and amoxicillin (J01) were prescribed to 184 patients (37.6%), and the antiemetics and antinauseants ondansetron and granisetron (A04) were prescribed to 161 patients (32.9%).

4.2 Drug Prescriptions in Different Age Groups

Older patients were prescribed significantly more drugs than younger patients: adolescents were prescribed a mean of 5.9 drugs (95% CI 5.1–6.7), children 6.0 drugs (95% CI 5.4–6.5), and infants 4.7 drugs (95% CI 4.2–5.1). One-sided ANOVA showed statistically significant differences in the mean number of drugs prescribed between infants and children (p = 0.006). The top ten of all prescribed drugs differed among the age groups (Table 2).

4.3 Drug Prescriptions for Female and Male Patients

Female patients were prescribed a mean of 5.4 drugs (95% CI 4.9–5.9), whereas male patients were prescribed 5.6 drugs (95% CI 5.1–6.0). This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.680, t-test).

4.4 Routes of Administration (ROA)

Almost half of all prescriptions were prescribed for oral use (47%). The second most prescribed ROA was intravenous (32%), followed by rectal application (10%), inhalation (5%), nasal application (2%), topical application (1%), subcutaneous (1%), intramuscular (1%), and other routes (1%).

4.5 Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

Therapeutic drug monitoring was prescribed for ten different active ingredients. The most frequent were tacrolimus (11 prescriptions with TDM) and gentamicin (9 prescriptions with TDM). Furthermore, TDM was ordered for the following active ingredients: mycophenolic acid (7), phenobarbital (4), lamotrigine (3), valproic acid (2), brivaracetam (2), sirolimus (1), ciclosporin (1), levetiracetam (1).

4.6 The 20 Most Frequently Prescribed Drugs

As presented in Table 3, by far the most frequently prescribed active ingredient was paracetamol in 379 (77.5%) patients: 153 (31.3%) received it as regular medication, 198 (40.5%) prescribed “as needed,” and 28 (5.7%) had both regular and “as needed” paracetamol prescriptions.

4.7 Prescribing Errors and Characteristics of the Drugs and Patients

Most prescribing errors were of minor severity, NCC MERP grade A–D. In Table 4, the overall error rates and the rates of potentially harmful errors (PHE) are displayed for the ten most frequently prescribed active ingredients, for the four most common routes of administration, for female and male patients, and for the four age groups. The error rate of PHE did not differ significantly between routes of administration. The error rate of PHE between age groups differed statistically significantly (p = 0.024), with children experiencing more PHE than infants (p = 0.029). Female and male patients showed a significant difference in PHE overall (p = 0.035), and in the age group of children between 2 and 11 years (p = 0.026).

We investigated the PCNE type of errors that occurred in the top ten active ingredients and found the following peculiarities:

-

13 of the 24 PHE that occurred in paracetamol prescriptions were dosing errors (PCNE 3).

-

There were no underdosing errors (PCNE 3.1) observed with ibuprofen.

-

The high rate of PHE in nalbuphine prescriptions was a recurring error: the maximum number of repetitions allowed in case of acute pain was lacking.

-

Cefazolin was prescribed most of the times for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. A frequent error we detected was that the prescription was not stopped after surgery. These errors were rated as PCNE 1.2 “no indication for drug” and to be of minor harm.

-

83% of the errors that occurred in salbutamol prescriptions were due to lacking information (PCNE 5.2), but of minor severity.

-

Underdosing errors (PCNE 3.1) were observed most frequently with paracetamol (pain treatment) and midazolam (seizures emergency treatment).

-

Overdosing errors (PCNE 3.2) were observed most frequently with paracetamol (pain/fever treatment).

-

An inappropriate duplication of therapy (PCNE 1.4) occurred most often with drugs for the nervous system (N) and in particular with analgesics (N02).

5 Discussion

5.1 Drugs Prescribed by Anatomical Class and Therapeutic Group (ATC Levels 1 and 2)

The exposure prevalence of patients receiving a drug for the nervous system (N) is very high, at 86.5%. It must be considered that we only included patients who were actually prescribed at least one drug. Patients without any drug prescription were excluded. This influences the rate of patients that received a certain drug in relation to the total number of patients.

The three predominant ATC classes N, alimentary system (A), and anti-infectives for systemic use (J) were the same as found by Rashed et al. [15], but our findings differ regarding the classes respiratory system (R) and musculoskeletal system (M). In our study, class M was prescribed more frequently and class R less frequently. Rauch et al. [16] also found these three classes (N, A, and J) to be predominant in the hospital care setting, but found anti-infectives (J) to be the class with the highest frequency of prescription, whereas we found drugs for the nervous system to be the most frequently used.

The percentage of patients prescribed an analgesic (81.8% of patients) was higher in our study than found by Botzenhardt et al. [13]. They found that 56.8% of all patients received analgesics, including those without any drug prescription. If we correct our rate of 81.8% by calculating the rate including patients without any drug prescription, the rate is 76.1%, which is still considerably higher than Botzenhardt’s rate. At the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, an elaborate pain concept exists, which is based on international guidelines [27, 28], and regular pain assessment is an important tool [29]. Considering the prevalence of pain in hospitalized pediatric patients of 59–94% [30], the high prescription rate of analgesics appears to be reasonable. In addition, N02 analgesics such as paracetamol and metamizole were not only prescribed as analgesics, but also as antipyretics or spasmolytics (metamizole), which might have contributed to the high prescription rate.

5.2 Drug Prescriptions in Different Age Groups

Not surprisingly, cholecalciferol was the second most prescribed drug for infants and toddlers, as it is recommended for every infant up to the age of 1 year to take daily 400–500 E of cholecalciferol [31].

Children and adolescents have a similar pattern of drug prescriptions with the same five most frequently prescribed drugs, with the only difference in ibuprofen and ondansetron ranking.

The fact that older patients were prescribed more drugs than younger patients was also seen by Rashed et al. [15].

5.3 Drug Prescriptions for Female and Male Patients

We did not find a difference in the number of prescribed drugs for female and male patients. This contradicts the finding of Sturkenboom et al. [32], who described a difference in the number of prescribed drugs with an age-related gender reversal: older girls (over 10 years of age) were prescribed more drugs than boys of the same age, whereas in younger patients it was opposite.

Earp et al. [33] reported that boys are being rated to experience more pain than girls in pediatric pain assessment, suggesting that a gender bias exists in pediatrics. We compared the mean number of prescribed analgesics (paracetamol, metamizole, ibuprofen, and nalbuphine) for female and male patients, and found no difference: females were prescribed 2.6 analgesics/patient and males 2.5 analgesics/patient (p = 0.592). Therefore, we could not confirm the results of Earp et al. [33].

5.4 Routes of Administration (ROA)

The pattern of ROAs prescribed was similar to the pattern reported by Rashed et al. [15], with oral being the most frequent route, followed by intravenous administration. Only the rate of rectal route was remarkably higher with 10% versus 2.5% of prescriptions, which shows the high acceptability of the rectal route in the German-speaking part of Switzerland [34].

5.5 Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

TDM practice in pediatrics has not yet been well described [35]. Not surprisingly, the main therapeutic areas covered by TDM in our hospital were antibiotics, immunosuppressants, and antiepileptic drugs. Our findings offer an insight into TDM practice in a tertiary care hospital in Switzerland.

5.6 The 20 Most Frequently Prescribed Drugs

Paracetamol was by far the most frequently prescribed drug. This result is not surprising, as paracetamol is the analgesic and antipyretic drug of choice for children [36]. The high rate of metamizole prescriptions is a peculiarity in countries such as Switzerland, Germany, or Austria. A recent study of Zahn et al. [37] found 31.7% of pediatric inpatients (university hospital) were prescribed metamizole, which is comparable to our findings of 37.4%. In the study of Zahn, metamizole was predominantly (about 90%) administered intravenously (i.v.), whereas in our hospital, the rate of oral administration was 55% and that of i.v. administration was 43%.

Roughly half of our top 20 list was included in the top 40 list of most frequently used drugs in pediatric hospitals in Switzerland as described by Tilen et al. [18], except for the following: cholecalciferol, nalbuphine, salbutamol, cefazolin, oxymetazoline, diazepam, enoxaparin, clonazepam, acetylsalicylic acid, levetiracetam, clemastine. The gap between our findings might be due to the fact that our study focused on pediatric patients on general wards, whereas the data of Tilen et al. covered all drugs used at the hospitals (including emergency department, pediatric/neonatal intensive care unit, oncology, psychiatry, ambulatory patients, etc.).

Our top three active ingredients were also found as top three drugs in Germany in the study by Rashed et al. [15], but in a different order. Di Paolo et al. [17] also found, for the French-speaking part of Switzerland, paracetamol and ibuprofen to be the most frequently prescribed active ingredients. Ranking third, they listed normal saline (NS) as nose drops which does not appear in our top 20 list as we did not document use of NS.

In salbutamol prescriptions, it is noteworthy that the number of prescriptions was remarkably higher than the number of patients prescribed salbutamol. Salbutamol dosages are adjusted to the symptoms in the course of the treatment, and this adjustment generates a new prescription in the CPOE each time.

5.7 Prescribing Errors and Characteristics of the Drugs and Patients

The finding that no underdosing errors occurred in ibuprofen prescriptions contradicts the finding of Milani et al. [38], who found underdosing errors to be frequent in acute pain management with paracetamol and ibuprofen. An explanation for this might be the clear dosing recommendations used in our hospital by Swisspeddose [18] and PEDeDose [39].

The typical nalbuphine error that occurred frequently (lacking number of maximum repetitions on demand) could be prevented by further development of the CPOE with integrated “must” field for the number of repetitions. The very low rate of PHE for cholecalciferol is not surprising, as it is a low-risk drug.

We found that dosing errors were frequent in paracetamol and midazolam. As paracetamol was by far the most frequently prescribed drug, it is not surprising that it is also at the top of the table in terms of dosing errors. Midazolam, which is used in emergency treatment of seizures, is often underdosed. This suggests that the on-demand prescription for emergency seizure treatment contains a high rate of prescribing errors. Causes for this finding might be lack of adaption of the dosages on current patients’ weight, or that too little attention was paid to the reserve medication because it was not needed in the current scenario.

5.7.1 ROA

We found no difference in the error rates between the different ROAs and could not find literature supporting the idea that prescribing errors occur more often in certain ROAs. There are only studies about errors involving the ROA itself [40]. Therefore, we assume that the chosen ROA does not influence prescribing error rate.

5.7.2 Age Groups

Children had a statistically significantly higher rate of PHE than infants. As the risk for an error increases with the number of prescribed drugs and as children were prescribed significantly more drugs than infants, this is a plausible finding. Condren et al. [41] found children between 0 and 4 years to be at highest risk for experiencing a prescribing error. As they used other age groups, our results are not comparable. In the study of Glanzmann et al. [42] on a pediatric intensive care unit in our hospital, infants (28 days to 1 year) and adolescents had higher error rates than toddlers and children. Maaskant et al. [43] found newborn and infants to be at the highest risk of all age groups, which contradicts our finding. As pediatric patients are a heterogeneous population, it would be useful if future research would focus on differences in prescribing errors in different age groups.

5.7.3 Gender

Our result shows a relevant gender gap, with a greater risk for female pediatric patients and especially female children, for experiencing a PHE error than male patients. The overall error rate did not differ significantly, but only the rate of potentially harmful errors. This is a surprising finding with possible explanations being gender bias of the prescribers, a bias in the rating of error severity, or that this is a false-positive finding. We could not find a difference in the profile of drug prescriptions between female and male patients that would explain the higher PHE rate in females.

In adults, gender bias in medicine is known to impact treatment of patients [44], but little is known about gender bias in prescribing errors in pediatrics. To our knowledge there is no large study that investigated the difference in error rates between female and male pediatric patients. As there are no other studies that investigated differences in error rates between female and male pediatric patients, further research is needed to estimate whether there is a difference in potentially harmful prescribing errors, and if so, what the contributing factors are.

5.8 Limitations

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and the fact that we investigated the prescribing patterns of a random sample in a single center, which may weaken the generalizability of our results. Therefore, our study may not be comparable with other drug utilization studies, as we conducted a secondary analysis of data that were captured for another study [19]. Nevertheless, we analyzed a large number of patients and validated our findings through review by a second rater (previous publication [19]). The rater had access to all patient data for evaluation of the prescribing errors.

5.9 Interpretation

Prescribing patterns on pediatric general wards in Switzerland are similar to those in other countries, though there are features specific to the German-speaking area: high rates of metamizole prescriptions and higher rates of rectal administration than in other countries. Prescribing errors occurring frequently in certain active ingredients such as nalbuphine and cefazoline demand a closer look at an institution level. We seem to be the first to describe a difference in the error rate between male and female pediatric patients.

5.10 Further Research

In the future, the possible gender bias in pediatric patients should be considered and future studies should investigate whether there really is a difference in prescribing error rates between female and male pediatric patients, and what the reasons for this difference might be.

6 Conclusions

In this study we describe the drug prescribing patterns on pediatric general wards in a university children’s hospital in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. The most frequently prescribed drugs were paracetamol, metamizole, and ibuprofen. The high rate of metamizole prescriptions is typical for German-speaking countries. The rate of patients prescribed an analgesic (81.8%) is higher than in other studies, and may be interpreted as a good coverage of pain in pediatric patients. The most frequently used route of administration was oral followed by intravenous, with a considerably high rate of rectal administration. Cefazolin and nalbuphine had the highest rates of prescribing errors, which must be addressed in future quality assurance measures. A significant difference in the prescribing error rate occurred between the age groups of children and infants and between female and male patients, which requires further investigation.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to sensitivity, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ATC:

-

Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification System

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPOE:

-

Computerized physician order entry

- NCC MERP:

-

National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting

- PCNE:

-

Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe

- PHE:

-

Potentially harmful error

- ROA:

-

Route of application

- TDM:

-

Therapeutic drug monitoring

References

Global patient safety action plan 2021–2030: towards eliminating avoidable harm in health care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, McKenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114–20.

Gates PJ, Baysari MT, Gazarian M, Raban MZ, Meyerson S, Westbrook JI. Prevalence of medication errors among paediatric inpatients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2019;42(11):1329–42.

Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD, Wong ICK. The incidence and nature of prescribing and medication administration errors in paediatric inpatients. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(2):113–8.

Neubert A, Taxis K, Wong ICK. Drug utilization in the paediatric population. In: Elseviers M, Wettermark B, Almarsdóttir AB, Andersen M, Benko R, Bennie M, Eriksson I, Godman B, Krska J, Poluzzi E, Taxis K, Vlahović-Palčevski V, Stichele RV, editors. Drug utilization research. 2016;248–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118949740.ch24.

Mesek I, Nellis G, Lass J, Metsvaht T, Varendi H, Visk H, et al. Medicines prescription patterns in European neonatal units. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(6):1578–91.

Rosli R, Dali AF, Abd Aziz N, Abdullah AH, Ming LC, Manan MM. Drug utilization on neonatal wards: a systematic review of observational studies. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:27.

Gouyon B, Martin-Mons S, Iacobelli S, Razafimahefa H, Kermorvant-Duchemin E, Brat R, et al. Characteristics of prescription in 29 level 3 neonatal wards over a 2-year period (2017–2018). An inventory for future research. PLoS One. 2019;14(9): e0222667.

Krzyżaniak N, Pawłowska I, Bajorek B. Review of drug utilization patterns in NICUs worldwide. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41(6):612–20.

Taine M, Offredo L, Weill A, Dray-Spira R, Zureik M, Chalumeau M. Pediatric outpatient prescriptions in countries with advanced economies in the 21st century: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4): e225964.

Luthander J, Bennet R, Nilsson A, Eriksson M. Antimicrobial use in a Swedish pediatric hospital: results from eight point-prevalence surveys over a 15-year period (2003–2017). Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(9):929–33.

Menchine M, Lam CN, Arora S. Prescription opioid use in general and pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20190302.

Botzenhardt S, Rashed AN, Wong IC, Tomlin S, Neubert A. Analgesic drug prescription patterns on five international paediatric wards. Paediatr Drugs. 2016;18(6):465–73.

Egunsola O, Choonara I, Sammons HM. Anti-epileptic drug utilisation in paediatrics: a systematic review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2017;1(1): e000088.

Rashed AN, Wong IC, Wilton L, Tomlin S, Neubert A. Drug utilisation patterns in children admitted to a paediatric general medical ward in five countries. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2015;2(4):397–410.

Rauch E, Lagler FB, Herkner H, Gall W, Sauermann R, Hetz S, et al. A survey of medicine use in children and adolescents in Austria. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(10):1479–87.

Di Paolo ER, Gehri M, Ouedraogo-Ruchet L, Sibailly G, Lutz N, Pannatier A. Outpatient prescriptions practice and writing quality in a paediatric university hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142: w13564.

Tilen R, Panis D, Aeschbacher S, Sabine T, Meyer Zu Schwabedissen HE, Berger C. Development of the Swiss Database for dosing medicinal products in pediatrics. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(3):1221–31.

Satir AN, Pfiffner M, Meier CR, Caduff Good A. Prescribing errors in children: what is the impact of a computerized physician order entry? Eur J Pediatr. 2023;182(6):2567–75.

EMA. ICH E11 (R1) guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population. 2017 [cited 2022 25.11.2022]; international-conference-harmonisation-technical-requirements-registration-pharmaceuticals-human-use_en-1.pdf. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-e11r1-guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-pediatric-population-revision-1_en.pdf.

ATC/DDD Index 2022. 2021 2021-12-14 [cited 2022 2022-08-12]. https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/.

Association PCNE. The PCNE CLassification V 9.1. 2020 [cited 2022 20.06.2022]. Classification for Drug related problems.

Schindler E, Richling I, Rose O. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) drug-related problem classification version 9.00: German translation and validation. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):726–30.

Forrey RA, Pedersen CA, Schneider PJ. Interrater agreement with a standard scheme for classifying medication errors. Am J Health Syst Pharm: Off J Am Soc Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(2):8.

Garfield S, Reynolds M, Dermont L, Franklin BD. Measuring the severity of prescribing errors: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2013;36(12):1151–7.

Prevention NCCfMERa. NCC MERP index for categorizing medication errors algorithm. NCC MERP; 2001.

Core curriculum for professional education in pain. Seattle: IASP Press International Association for the Study of Pain; 2005.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Task Force on Pain in Infants and Adolescents. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108(3):793–7.

Twycross A. Guidelines, strategies and tools for pain assessment in children. Nurs Times. 2017;113(5):18–21.

Simons J, Carter B, Craske J. Developing a framework to support the delivery of effective pain management for children: an exploratory qualitative study. Pain Res Manag. 2020;2020:5476425.

SwissPedDose. Swiss database for dosing medicinal products in pediatrics. [cited 2022 25.11.2022]. https://db.swisspeddose.ch/de/.

Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM, Nicolosi A, Murray ML, Neubert A, Caudri D, et al. Drug use in children: cohort study in three European countries. BMJ. 2008;24(337): a2245.

Earp BD, Monrad JT, LaFrance M, Bargh JA, Cohen LL, Richeson JA. Featured article: gender bias in pediatric pain assessment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2019;44(4):403–14.

Lava SA, Simonetti GD, Ferrarini A, Ramelli GP, Bianchetti MG. Regional differences in symptomatic fever management among paediatricians in Switzerland: the results of a cross-sectional Web-based survey. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(1):236–43.

Leung D, Ensom MHH, Carr R. Survey of therapeutic drug monitoring practices in pediatric health care programs across Canada. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2019;72(2):126–32.

de Martino M, Chiarugi A. Recent advances in pediatric use of oral paracetamol in fever and pain management. Pain Ther. 2015;4(2):149–68.

Zahn J, Eberl S, Rödle W, Rascher W, Neubert A, Toni I. Metamizole use in children: analysis of drug utilisation and adverse drug reactions at a German University Hospital between 2015 and 2020. Paediatr Drugs. 2022;24(1):45–56.

Milani GP, Benini F, Dell’Era L, Silvagni D, Podestà AF, Mancusi RL, et al. Acute pain management: acetaminophen and ibuprofen are often under-dosed. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(7):979–82.

Higi L, Käser K, Wälti M, Grotzer M, Vonbach P. Description of a clinical decision support tool with integrated dose calculator for paediatrics. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(2);679–89.

Lesar TS. Medication prescribing errors involving the route of administration. Hosp Pharm. 2006;41(11):1053–66.

Condren M, Honey BL, Carter SM, Ngo N, Landsaw J, Bryant C, et al. Influence of a systems-based approach to prescribing errors in a pediatric resident clinic. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(5):485–90.

Glanzmann C, Frey B, Meier CR, Vonbach P. Analysis of medication prescribing errors in critically ill children. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(10);1347–55.

Maaskant JM, Vermeulen H, Apampa B, Fernando B, Ghaleb MA, Neubert A, et al. Interventions for reducing medication errors in children in hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10(3):Cd006208.

Hamberg K. Gender bias in medicine. Womens Health. 2008;4(3):237–43.

Acknowledgments

We thank Beat Bangerter from the University Children’s Hospital Zurich for his tireless technical support in the creation and use of the database.

Funding

This article was not funded, but the previous study (Prescribing errors in children: what is the impact of a computerized physician order entry? [19]) was funded by the grant for the scientific project of national reach 2014 of the Swiss Association of Public Health Administration and Hospital Pharmacists (GSASA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Principal investigator and supervision of the thesis of AS: AC—Conception, design, and methods: AC, AS—Data collection: AS—Medication review: AS, MP—Data analysis and initial manuscript: AS—Review, editing and final approval of the manuscript: AC, AS, MP, CM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Zurich granted approval (PB_2019-00030, project related to subsequent use of nongenetic personal health data).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent for further use of their health-related data was obtained of all patients.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Satir, A.N., Pfiffner, M., Meier, C.R. et al. Prescribing Patterns in Pediatric General Wards and Their Association with Prescribing Errors: A Retrospective Observational Study. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 619–629 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00392-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00392-0