Abstract

Background

Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are at increased risk of pancreatitis. Data from a global safety database (GSD) were queried to identify risk factors for pancreatitis in vedolizumab-treated patients with IBD.

Methods

Takeda’s GSD was retrospectively queried for case reports (CRs) of adverse events (AEs) following vedolizumab treatment, from licensure (May 20, 2014) through March 31, 2021. Unsolicited and solicited CRs of pancreatitis were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) High-Level Term “Acute and chronic pancreatitis.” To examine factors associated with severe pancreatitis, serious CRs (serious AEs [SAEs]) were compared with SAEs from a comparator group of 600 random non-pancreatitis AEs. Comparisons were performed using t, χ2, and Fisher’s exact tests. Logistic regression was performed to adjust for covariates allowing backward selection.

Results

In total, 196 patients reported pancreatitis in > 700,000 patient-years of vedolizumab exposure. Pancreatitis was serious in 195 patients (99.5%), and non-pancreatitis AEs were serious in 195 of 600 (32.5%) in the random comparator group. In the pancreatitis group, 17 patients (8.7%) had a known history of pancreatitis versus none in the random comparator group. Younger age, vedolizumab indication of ulcerative colitis, concomitant medications (with a risk for pancreatitis), pancreatitis history, and comorbid conditions (especially ongoing pancreatitis) were associated with development of severe pancreatitis.

Conclusions

These analyses identified factors associated with pancreatitis SAEs in patients with IBD treated with vedolizumab, but do not suggest an increased risk of pancreatitis with vedolizumab. These findings will help inform which patients treated for IBD might have an elevated risk, regardless of treatment.

Plain Language Summary

People with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are at increased risk for inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis). Vedolizumab (VE-doe-LIZ-ue-mab), approved for the treatment of IBD, works by preventing cells that cause inflammation from entering the gut lining. We looked at a worldwide safety database to identify factors that may increase the risk for pancreatitis in people with IBD receiving vedolizumab. Since vedolizumab’s approval in 2014, 196 people had pancreatitis in > 700,000 person-years of vedolizumab exposure. Person-years account for the number of people in the study and for duration of treatment. Most (195 of 196) people with pancreatitis had serious cases. In a comparator group of people with random side effects other than pancreatitis, about one in three people had serious side effects. Among the 195 people with serious pancreatitis, 17 had a history of pancreatitis, compared with none in the comparator group. We found several factors that may increase the risk for serious pancreatitis: younger age, treatment for ulcerative colitis, previous pancreatitis, taking other medicines, and having additional medical conditions. The relatively few identified cases of pancreatitis from over 700,000 years of patient exposure does not suggest an increased risk for developing pancreatitis. These findings could be used to identify people treated for IBD who may have an increased risk of developing pancreatitis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are at an increased risk of pancreatitis; however, the role of IBD therapy in the development of pancreatitis is currently unclear. |

Data captured in a global safety database were queried to identify risk factors for developing pancreatitis among patients treated with vedolizumab, a gut-selective anti–lymphocyte trafficking agent. |

Risk factors associated with serious pancreatitis included age, indication of use, use of concomitant medications, pancreatitis history, and comorbid conditions. Such findings help to inform which patients treated for IBD might have an elevated risk of developing pancreatitis, regardless of treatment. |

1 Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), affects approximately 6.8 million people worldwide [1], with the highest prevalence of cases reported in Europe (505 and 322 cases per 100,000 for UC and CD, respectively) and North America (286 and 319 cases per 100,000 for UC and CD, respectively) [2]. The American College of Gastroenterology and the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation recommend administration of corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics (anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha [anti-TNFα] or anti-α4β7 integrin therapy) for inducing and/or maintaining remission in patients with UC or CD [3,4,5,6]. 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) are also recommended for the treatment of patients with UC [3, 5].

Vedolizumab is a gut-selective anti–lymphocyte trafficking agent approved for the treatment of moderate to severe UC and CD [7, 8]. It is a humanized anti-α4β7 integrin monoclonal antibody that selectively antagonizes gastrointestinal integrin receptors, consequently reducing lymphocyte trafficking into the intestine [9]. The efficacy and safety profile of vedolizumab treatment in patients with UC and CD has been demonstrated in the clinical setting [10,11,12].

Although IBDs mainly affect the bowel, extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are frequently observed in patients with UC and CD [13,14,15]. These EIMs can present in a wide range of organ systems, including the dermatological, hepatopancreatobiliary, musculoskeletal, ocular, pulmonary, and renal systems [15]. EIMs of the hepatopancreatobiliary system are estimated to affect approximately 50% of patients with IBD during the course of their disease, and include, among others, pancreatic disorders [13, 14].

These pancreatic disorders represent a heterogeneous group of pancreatic manifestations including acute, chronic, and autoimmune pancreatitis, asymptomatic imaging abnormalities, and asymptomatic elevation of pancreatic enzymes [14]. Acute pancreatitis is one of the most common pancreatic pathologies observed in patients with IBD, among whom the odds of developing acute pancreatitis has been estimated at 3.11 times higher (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.93–3.30) than that of the general population [16]. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis reported an elevated risk of developing acute pancreatitis in patients with IBD compared with patients without IBD (odds ratio 2.78 [95% CI 2.40–3.22]) [17]. When data are stratified by IBD type, the patient groups with UC and CD were both more likely to develop acute pancreatitis than patients without IBD (pooled risk estimates [95% CI] of 3.62 [2.99–3.48] for UC and 2.24 [1.85–2.71] for CD) [17].

Risk factors associated with developing pancreatitis are well documented. Smoking, alcohol abuse, and disease-related risk factors such as hypertriglyceridemia, autoimmune diseases, genetic mutations, infections, gall bladder disorder, IBD, and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) are extensively reported in the literature [18,19,20]. Cases of pancreatitis are also associated with the medical treatments used to treat patients with IBD such as endoscopic procedures and drug-induced pancreatitis [16, 18]. Drug-induced pancreatitis has been reported for patients taking first-line IBD treatments including 5-ASAs (mesalazine) and thiopurines (azathioprine, mercaptopurine, and sulfasalazine) [16]. Only a few cases of drug-induced pancreatitis have been reported for patients with IBD treated with biologics such as vedolizumab [21,22,23]. Reported incidences of drug-induced pancreatitis are generally collected via spontaneous case reports; as such, true incidences are likely to be underestimated.

Distinguishing IBD from pancreatitis in patients is often difficult owing to similarities in the clinical symptoms presented; for example, abdominal pain and diarrhea are typically experienced by both patient populations [15]. In addition, determining if the development of pancreatitis is related to the pathogenesis of IBD (an EIM) or from an extraintestinal complication, such as side effects of the IBD therapy, further complicates determination of etiology [16].

This study aimed to identify factors associated with pancreatitis in patients undergoing treatment for IBD among data captured in a large global safety database, to inform who might benefit from close monitoring, regardless of specific treatment.

2 Materials and Methods

Takeda’s Global Safety Database was queried for case reports of adverse events (AEs) following vedolizumab treatment, from licensure (May 20, 2014) through March 31, 2021, representing > 700,000 patient-years of exposure to vedolizumab at the time of the analysis. The Global Safety Database consists of all (serious and non-serious) post-marketing reports of AEs forwarded to Takeda by healthcare providers, patients, regulatory authorities, literature, investigators conducting post-marketing studies, and patient support programs. Serious AEs (SAEs) reported in clinical trials are also entered into the database. The estimated number of patient-years of exposure is calculated by the total number of vials sold (considering package size) divided by 6.5 (dosing interval considering 52 weeks per year) plus the total number of pens sold (considering package size) divided by 26 (dosing interval considering 52 weeks per year).

Unsolicited and solicited case reports of pancreatitis were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 24.0) High-Level Term “Acute and chronic pancreatitis,” which included the following Preferred Terms: “pancreatitis,” “pancreatitis acute,” “autoimmune pancreatitis,” “obstructive pancreatitis,” “pancreatitis necrotizing,” “pancreatitis relapsing,” and “chronic pancreatitis.” Unsolicited spontaneous reported cases of AEs were received directly from patients, healthcare professionals, regulatory authorities, and scientific literature; solicited reported cases of AEs were obtained from interventional clinical studies, observational studies, registries, patient support programs, and market research programs.

A comparator group was then extracted from Takeda’s Global Safety Database using data from 600 case reports of random non-pancreatitis AEs among patients with IBD treated with vedolizumab. In order to examine factors associated with serious pancreatitis, case reports in the comparator group meeting the regulatory definition of serious criteria were compared with serious case reports (SAEs) of pancreatitis. An AE was defined as serious if it (1) resulted in death; (2) was considered life-threatening; (3) required inpatient hospitalization or prolonged existing hospitalization; (4) resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity; (5) was a congenital anomaly/birth defect; and/or (6) was considered a medically important event or reaction. Case reports were returned in chronological order following query of the database and randomized using the randomization function in Microsoft Excel to eliminate a possible time effect.

Case reports were medically reviewed, and details of patient demographics (age and sex), vedolizumab treatment indication, medical history, use of concomitant medications, comorbid conditions, and time to AE onset were extracted.

Unadjusted comparisons were performed using t tests for continuous data, and χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data. A logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for covariates that allowed backward selection. Baseline characteristics included in the model were age, sex, vedolizumab indication for use, medical history, use of concomitant medications, and comorbid conditions. To account for differences in patient baseline characteristics between pancreatitis and random case reports, an adjusted analysis was performed using inverse probability treatment weighting to reduce biases on estimates of average group effects. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Extraction of Pancreatitis Group from the Global Safety Database

Over the approximate 7 years since the first regulatory approval of vedolizumab (> 700,000 patient-years of exposure to vedolizumab at the time of the analysis), a total of 196 patients in Takeda’s Global Safety Database were reported to have pancreatitis. The onset of symptoms of pancreatitis in two of these patients was positively re-challenged and reported previously [21, 22]. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

3.2 Comparison of Pancreatitis Group (SAEs) with Random Comparator Group

The majority of patients in the pancreatitis group reported SAEs (99.5%, n = 195/196). SAEs were reported by approximately one-third of patients in the random comparator group (32.5%, n = 195/600). The description and analyses used for the comparison of the pancreatitis group with the random comparator group were limited to patients with SAEs (195 in each group).

Table 2 summarizes patient demographics and clinical characteristics in patients reporting SAEs in the pancreatitis and random comparator groups. Patients in the pancreatitis group were younger (mean age 39.5 years) compared with patients in the random comparator group (48.8 years). Approximately equal numbers of patients were male (n = 92) and female (n = 90) in the pancreatitis group, whereas there were more females than males in the random comparator group (n = 115 and n = 75, respectively). For case reports with vedolizumab indication specified, the highest proportion of patients in the pancreatitis group had UC (40.5%), whereas CD was most often reported in the random comparator group (45.1%). An unadjusted comparison between patients with SAEs showed that females (p = 0.015) and CD (p = 0.001) were more common in the random comparator group versus the pancreatitis group.

A higher proportion of patients in the pancreatitis group had a relevant medical history compared with patients in the random comparator group (13.3% [n = 26/195] vs 2.1% [n = 4/195], respectively). Among the patients in the pancreatitis group, 8.7% (n = 17/195) had a history of pancreatitis, whereas none in the random comparator group had a history of pancreatitis.

In the pancreatitis group, 2.6% (n = 5/195) of patients had pancreatitis as a comorbid condition prior to exacerbation of the condition, usually leading to hospitalization and reporting it as an SAE, versus none in the random comparator group. Cholelithiasis was the most frequently reported comorbid condition in the pancreatitis group (7.2% [n = 14/195 patients]), whereas hyperlipidemia and diabetes were the most frequently reported in the random comparator group (5.6% [n = 11/195] and 5.1% [n = 10/195], respectively) (Fig. 1).

Alcohol abuse was reported for 0.5% of patients, and gall bladder disorder, hyperlipidemia, pancolitis, and PSC were all reported as comorbid conditions for 1.0% of patients in the pancreatitis group. Gall bladder disorder (0.5%), pancolitis (0.5%), and pancreatic cyst (1.0%) were reported for patients in the random comparator group.

The percentage of patients taking the five most common drugs in the pancreatitis group that have risk of developing pancreatitis listed in the prescribing information or summary of product characteristics is shown in Fig. 2. Although patient numbers are small, it is noted that infliximab was more often taken by patients in the pancreatitis group (n = 10) than the random comparator group (n = 1). Statins were more frequently taken by patients in the random comparator group (n = 10 vs n = 3 in the pancreatitis group), who were older.

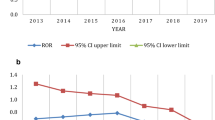

Time to SAE onset was reported for 13.8% (n = 27/195) of case reports in the pancreatitis group and 29.2% (n = 57/195) of case reports in the random comparator group. About half of the AEs were reported in year 1 for both the pancreatitis group and random comparator group (Fig. 3).

Results of the logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. Various factors including younger age, vedolizumab treatment indication for UC, use of concomitant drugs, history of pancreatitis, and presence of comorbid conditions were strongly associated with the development of pancreatitis.

4 Discussion

This retrospective cohort analysis using Takeda’s Global Safety Database of > 700,000 patient-years of exposure to vedolizumab at the time of analysis showed that a very small number of vedolizumab-treated patients with IBD reported pancreatitis (n = 196). Pancreatitis was serious in the majority of cases (n = 195).

In our analysis of serious case reports of pancreatitis that were reported to Takeda’s Global Safety Database, an approximately equal proportion of males (47.2%) and females (46.2%), with a mean age of 39.5 years, were included in the pancreatitis group. These findings are consistent with the accepted fact that UC and CD are known to affect men and women equally [24]. An unadjusted comparison between patients with SAEs showed that vedolizumab therapy for CD was more common in the random comparator group compared with the pancreatitis group (p = 0.001). This finding is consistent with a published analysis showing that patients with UC are more likely to develop acute pancreatitis than patients with CD, when compared with the general population [17]. Although a higher proportion of patients in the pancreatitis group were prescribed vedolizumab for UC therapy than the random comparator group (40.5 vs 38.5%, respectively), the difference was numerically minimal and not significant.

Of the concomitant medications evaluated (i.e., those with a risk of pancreatitis listed in the package insert), steroids and azathioprine were the most frequently taken by patients in both the pancreatitis and random comparator groups. This is consistent with corticosteroids and immunosuppressant therapies being recommended as first-line treatments for UC and CD [3, 25]. For patients in the pancreatitis group with relevant medical history available, 8.7% had a history of pancreatitis, whereas none in the random comparator group had a history of pancreatitis. PSC, diabetes, and cholelithiasis were the most frequently reported comorbid conditions for patients in the pancreatitis group, whereas hyperlipidemia and diabetes were the most common for patients in the random comparator group. The development of diabetes mellitus following an episode of acute pancreatitis is becoming more recognized, although the subtype of diabetes presenting in this context remains unclear [26].

Although time to SAE onset was reported infrequently for patients in both the pancreatitis and random comparator groups, available data extracted from Takeda’s Global Safety Database showed that the majority of SAEs occurred within the first year of starting vedolizumab. This is consistent with the literature, which reports onset of drug-induced pancreatitis within 2 days to 1 month post therapy, and up to 1 year in some cases [27]. Furthermore, these analyses were unable to control for other risk factors associated with pancreatitis; therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

In addition to the post-marketing case reports presented above, an integrated summary of safety data from six clinical trials evaluating vedolizumab in patients with IBD showed that only 0.7% of patients (n = 12/1723) taking vedolizumab developed acute or chronic pancreatitis; however, no association between taking vedolizumab and onset of pancreatitis was confirmed [28]. Furthermore, a literature search identified only three reported cases of pancreatitis in patients taking vedolizumab [21,22,23] (Online Resource 1, see the electronic supplementary material). Taken together, these findings do not support a risk of developing pancreatitis specific to vedolizumab treatment.

There were a few limitations of this analysis. This was a retrospective cohort analysis of AEs reported to a global safety database; therefore, the data presented herein are largely based on spontaneous case reports of AEs. Use of such data introduces the potential for reporting bias, which might in part explain the high rates of pancreatitis that were reported as SAEs. Furthermore, these case reports were frequently missing data. As such, the data should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the medical history of patients in the pancreatitis group included alcohol abuse [29], gall bladder disorder [30, 31], hyperlipidemia [32], pancolitis [33], and PSC [34], all of which are known risk factors for pancreatitis. The type of data included in the case reports was also limited; for example, duration of illness was seldom included. The higher the number of data types available for inclusion in an analysis set, the higher the number of potential risk factors analyzed.

5 Conclusions

This retrospective analysis identified several factors associated with 196 spontaneous case reports of pancreatitis captured in our large global safety database of > 700,000 patient-years of exposure to vedolizumab at the time of the analysis. Quantitative analysis of data extracted from the case reports indicates that younger age, vedolizumab indication for UC, concomitant medications, a history of pancreatitis, and comorbid conditions (especially ongoing pancreatitis) may be associated with the development of pancreatitis to the degree that it is reported as an SAE. Given that only 196 cases of pancreatitis were identified from the Global Safety Database of over 700,000 patient-years of exposure, our findings suggest that there is no evidence of a causal relationship between patients taking vedolizumab and the risk of pancreatitis. Findings can inform which patients undergoing treatment for IBD might have an elevated risk of developing pancreatitis, regardless of what treatment they are receiving. These findings are hypothesis generating, and further research to prospectively identify risk factors for developing pancreatitis in patients with IBD undergoing treatment may be of interest.

References

GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17–30.

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–78.

Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413.

Sulz MC, Burri E, Michetti P, Rogler G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Seibold F, Swiss IBDnet an official working group of the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Treatment algorithms for Crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2020;101(Suppl 1):43–57.

Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, Kucharzik T, Adamina M, Annese V, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(1):2–17.

Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):4–22.

Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Entyvio (Vedolizumab) prescribing information. Lexington: Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2021.

Takeda Pharma A/S. Entyvio INN-Vedolizumab summary of product characteristics. Vallensbaek: Takeda Pharma A/S; 2021.

Wyant T, Fedyk E, Abhyankar B. An overview of the mechanism of action of the monoclonal antibody vedolizumab. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(12):1437–44.

Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel J-F, Sandborn WJ, GEMINI 1 Study Group, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):699–710.

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel J-F, Sands BE, GEMINI 2 Study Group, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):711–21.

Loftus EV Jr, Feagan BG, Panaccione R, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, et al. Long-term safety of vedolizumab for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(8):1353–65.

Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, Lakatos PL, Navarini A, Rogler G. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(8):1982–92.

Ramos LR, Sachar DB, DiMaio CJ, Colombel J-F, Torres J. Inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis: a review. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(1):95–104.

Antonini F, Pezzilli R, Angelelli L, Macarri G. Pancreatic disorders in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2016;15(7):276–82.

Tél B, Stubnya B, Gede N, Varjú P, Kiss Z, Márta K, et al. Inflammatory bowel diseases elevate the risk of developing acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2020;49(9):1174–81.

Pedersen JE, Ängquist LH, Jensen CB, Kjærgaard JS, Jess T, Allin KH. Risk of pancreatitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease—a meta-analysis. Dan Med J. 2020;67(3):A08190427.

Weiss FU, Laemmerhirt F, Lerch MM. Etiology and risk factors of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Visc Med. 2019;35(2):73–81.

Roberts SE, Morrison-Rees S, John A, Williams JG, Brown TH, Samuel DG. The incidence and aetiology of acute pancreatitis across Europe. Pancreatology. 2017;17(2):155–65.

Mayerle J, Sendler M, Hegyi E, Beyer G, Lerch MM, Sahin-Tóth M. Genetics, cell biology, and pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(7):1951–68.

Picardo S, So K, Venugopal K, Chin M. Vedolizumab-induced acute pancreatitis: the first reported clinical case. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017222554.

Lopez RN, Gupta N, Lemberg DA. Vedolizumab-associated pancreatitis in paediatric ulcerative colitits: functional selectivity of the α4β7 integrin and MAdCAM-1 pathway? J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(4):507–8.

Lin E, Katz S. Acute pancreatitis in a patient with ulcerative colitis on vedolizumab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(5): e44.

Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369(9573):1641–57.

Lichtenstein GR, Shahabi A, Seabury SA, Lakdawalla DN, Espinosa OD, Green S, et al. Lifetime economic burden of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis by age at diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):889–97.e10.

Richardson A, Park WG. Acute pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus: a review. Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36(1):15–24.

Balani AR, Grendell JH. Drug-induced pancreatitis: incidence, management and prevention. Drug Saf. 2008;31(10):823–37.

Colombel J-F, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn W, Danese S, D’Haens G, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66(5):839–51.

Olesen SS, Mortensen LH, Zinck E, Becker U, Drewes AM, Nøjgaard C, et al. Time trends in incidence and prevalence of chronic pancreatitis: a 25-year population-based nationwide study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2021;9(1):82–90.

Fousekis FS, Theopistos VI, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK. Pancreatic involvement in inflammatory bowel disease: a review. J Clin Med Res. 2018;10(10):743–51.

Fagagnini S, Heinrich H, Rossel J-B, Biedermann L, Frei P, Zeitz J, et al. Risk factors for gallstones and kidney stones in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10): e0185193.

Gan SI, Edwards AL, Symonds CJ, Beck PL. Hypertriglyceridemia-induced pancreatitis: a case-based review. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(44):7197–202.

Barthet M, Hastier P, Bernard JP, Bordes G, Frederick J, Allio S, et al. Chronic pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease: true or coincidental association? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2141–8.

Mertz A, Nguyen NA, Katsanos KH, Kwok RM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease comorbidity: an update of the evidence. Ann Gastroenterol. 2019;32(2):124–33.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Adele Blair, PhD, and Jon Waldron, PhD, of Excel Medical Affairs, and funded by Takeda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was sponsored by Takeda.

Conflict of interest

JFW, TV, TZ, and WS are employees of Takeda and hold stock/stock options in Takeda. LL was a fellow of Takeda at the time of the analyses. YC and AA were interns of Takeda at the time of the analyses.

Availability of data and material

The datasets, including the redacted study protocol, redacted statistical analysis plan, and individual participants’ data supporting the results reported in this article, will be made available within 3 months from initial request to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. The data will be provided after its de-identification, in compliance with applicable privacy laws, data protection, and requirements for consent and anonymization. Data are available upon request via application at https://search.vivli.org.

Ethics approval

Not applicable because data are from a global safety database that contains spontaneous post-marketing reports from patients and healthcare professionals.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

JFW and TV were responsible for the study design, implementation, and data extraction. TZ and YC conducted the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in interpreting the results, contributed to the preparation of this manuscript, and read and revised each draft. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for submission and agree to be accountable for the work.

Additional information

Laurie Lee, Yue Cheng and Alicia Ademi: Affiliation at the time this analysis was conducted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wernicke, J.F., Verstak, T., Zhang, T. et al. Predictors of Pancreatitis Among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated with Vedolizumab: Observation from a Large Global Safety Database. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 557–564 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00386-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00386-y