Abstract

Background

Several oral drugs are recommended to be taken with large amounts of water for reasons such as peptic ulcer prophylaxis. On the other hand, there are many patients with diseases that restrict water intake, and the actual frequency of patients receiving prescriptions in these conflicting situations is not clear.

Objective

Using a large claims database in Japan, this study aimed to determine the proportion of patients aged ≥ 75 years on fluid restriction who received drugs whose drug package insert mentioned “a large amount of water intake is needed when taking the drug”.

Methods

We performed a prescription survey of older patients over 75 years of age using the Japan Medical Data Centre (JMDC) claims database. Out of approximately 8800 oral drugs used in Japan, we defined 29 drugs for which package inserts noted that a large amount of water intake is recommended during drug administration. We defined diagnosis codes for some common diseases for which restricted water intake is likely recommended: heart failure (NYHA class III or IV), liver cirrhosis with ascites, and chronic kidney disease stage 5, including dialysis patients.

Results

Of 5968 patients aged ≥ 75 years (men 47.7%), 320 (5.4%) patients with heart failure (2.8%, n = 170), liver cirrhosis (0.7%, n = 40), or chronic kidney disease (1.9%, n = 113), diagnoses likely associated with the need for fluid restriction, were prescribed drugs for which abundant fluid at intake was recommended. Among 29 identified drugs, 15 drugs were administered to older patients over 75 years with fluid restriction due to said diseases.

Conclusions

Of patients 75 years and older with disease likely requiring water restriction, 5.4% faced the dilemma of following advice to restrict fluid intake due to their diagnoses or to adhere to instructions in drug package inserts to have abundant fluid intake when taking the drug. Our study raises awareness regarding the dilemma of water restriction and intake in clinical settings, highlighting the importance of considering individual patient needs. These real-world findings emphasize the need for information and guidelines to assist healthcare professionals in navigating this dilemma and making informed decisions for the benefit of their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For some drugs, it is recommended to drink large amounts of water when taking them internally. These drugs are being administered to patients aged 75 years and older with conditions that require fluid restriction. |

Approximately 5.4% of patients aged 75 years or older who were diagnosed with conditions likely to require the need for water restriction faced a conflicting situation where they were recommended to consume large amounts of water due to drug instructions despite their medical conditions. |

Health care providers need to take into account the background of individual patients and guide them to the optimal amount of water to drink. |

1 Introduction

Several diseases are associated with the risk of fluid overload, and because at-risk patients may develop life-threatening complications such as peripheral or central edema, it is important that they adhere to prescribed fluid restriction. The need for fluid restriction must be carefully considered in patients with heart failure (HF), liver cirrhosis (LC), and chronic kidney disease (CKD). This is especially critical for patients with severe stages of these diseases. Mortality rates for patients with HF with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III and IV were reportedly between 12.1 and 26.5% over 20 months [1], for patients with LC with a Child-Pugh score of B or C for 2 years 40% and 65%, respectively [2], and for patients with renal dysfunction CKD stages 5, 40–50% over 4.9 years [3].

While these and other conditions may require fluid restriction, package inserts for several drugs that are commonly prescribed to patients with these conditions contain instructions recommending the intake of large amounts of water with the drug to prevent gastrointestinal impairment, renal impairment, dehydration (due to severe reduction of body fluids, perspiration, and often accompanied by hypernatremia), and tumor lysis syndrome (potentially accompanied by hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hyperuricemia). However, in the case of the above-mentioned diseases, where fluid restriction is often mandatory, patients may be confused by package inserts that state they should drink large amounts of water.

Resolving these concerns may require much effort by medical staff in assessing individual situations, such as the need to control water intake and educate patients about symptoms. However, the proportion of drugs that may cause the above-mentioned dilemma is unknown. From an epidemiologic point of view, it is important to understand the frequency of such controversial situations, especially in patients aged ≥ 75 years with the diseases in question. Therefore, we performed a cross-sectional, descriptive, hypothesis-generating prescription survey of older patients over 75 years of age using claims data in Japan to assess the frequency of package insert recommendations advocating abundant water intake in said patients with fluid-restricting conditions.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The JMDC (Japan Medical Data Centre) claims database contains anonymized patient data. The cumulative dataset contains approximately 13 million subjects (inpatients, outpatients, and pharmacy claims). All patients in the JMDC database have social insurance that cover working people and their families. As of September 2021, the database represented 10.0% of the Japanese population [4].

Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) data is a comprehensive evaluation system for assessing medical fees for acute inpatient care in Japan. DPC data is used to calculate medical expenses by classifying patients according to their diseases and treatments and defining the daily hospitalisation cost for each classification [5]. The classification of dementia followed the classification established by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [6].

2.2 Identification of Drugs Included in the Analysis

We identified 29 drugs with package inserts stating “a large amount of water intake is recommended during drug administration” among approximately 8800 oral drugs (with approximately 2600 components) used for drug therapy in Japan [7]. Briefly, we used drug package inserts uploaded by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) [8] for drugs marketed prior to December 2019. We searched for the following phrases in the package insert: (1) “a lot of/a large amount of water when taking drug”, (2) “recommend taking enough water/hydration”. Among these drugs, we excluded the following: (1) magnesium oxide and magnesium sulphate, which require drinking large amounts of water only when used to prevent urinary or kidney stones and (2) desmopressin, which includes the word ‘hydration’ in the package insert but does not urge patients to drink water. We included tolvaptan (an aquaretic drug indicated for HF since 2010 and for LC since 2013) and sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (agents that among other actions also promote diuresis; indicated for HF and CKD since 2021), which have the pharmacological effects of a diuretic [9] while the package inserts state the need for ‘hydration’, that is, extra fluid may be needed to maintain an adequate hydration state to compensate for the drug-induced removal of water.

2.3 Definition for Diseases Requiring Water Restriction

Patients who were considered to require water intake restrictions were assessed for the following diagnoses and using the following criteria: (1) HF with NYHA class III or IV using DPC data [10], (2) LC with ascites assessed using the Child-Pugh score using DPC data [11], and (3) CKD stage 5 or 5D (N185) using International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) [12].

2.4 Primary and Secondary Endpoint

The primary endpoint was to determine the proportion of patients who could be exposed to the dilemma of either following the recommendation to drink a lot of water when taking a drug or following the advice to restrict water intake because of their underlying conditions of HF, LC, or CKD. The secondary endpoint was to descriptively show the distribution of patients who were administered drugs whose package inserts recommended high water intake.

2.5 Ethics Approval and Statistical Analysis

This study was based on the ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects in Japan. There was no requirement to obtain informed consent since the patient data were anonymized before being accessed. In addition, because of the use of anonymized data in this study, the review by the institutional ethics committee was waived. Age is provided as categorical data because of the protection for identification policy of the JMDC. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviations, or the number with percentage. We employed the chi-square test to analyze categorical data and the Mann–Whitney U-test to analyze continuous variables in the groups with and without treatments that require a large amount of water intake.

We conducted comparisons of patients’ backgrounds for the following sub-groups: (1) patients without a prescription requiring a large amount of water, (2) patients with a prescription requiring a large amount of water, (2.1) patients with a prescription for tolvaptan and SGLT2 inhibitors within group (2), and (2.2) patients with a prescription requiring a large amount of water without tolvaptan and SGLT2 inhibitors within group (2). Specifically, we compared (1) versus (2), (1) versus (2.1), and (1) versus (2.2) using the aforementioned statistical tests. Data analysis was performed using JMP® 16 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Case Identification and Patients’ Background

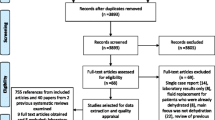

We used data from JMDC extracted from 273,932 inpatients over 75 years of age admitted between January and December 2019 (Fig. 1). After excluding patients with missing data, a total of 70,642 patients aged > 75 years were included in our study. Among them, 64,674 patients (men 46.6%; average body mass index (BMI) 22.0 ± 3.9 kg/m2) did not have prescriptions for drugs that require a large amount of water intake, while 5968 patients (men 47.7%; average BMI 22.3 ± 4.1 kg/m2) had such prescriptions (Table 1). Generally, the group with the prescriptions was older (p < 0.01) and had higher BMI (p < 0.01).

Among the patients with prescriptions, 3050 (men 51.3%; average BMI 22.8 ± 4.3 kg/m2) were treated with tolvaptan and/or SGLT2 inhibitors, while 3130 (men 44.2%; average BMI 21.8 ± 3.9 kg/m2) were treated with other drugs that require a large amount of water intake (Table 1). The tolvaptan or SGLT2 inhibitor group was older and had a higher BMI (p < 0.01) compared with the group without prescriptions. On the other hand, the ‘other drugs’ group was younger and had a lower BMI (p < 0.01) compared with the group without prescriptions.

Among the patients treated with tolvaptan or SGLT2 inhibitors, a higher proportion died (p < 0.01) and were transported by ambulance (p < 0.05), while a lower proportion had no dementia (p < 0.01) compared with patients without drugs requiring a large amount of water intake (Table 1). On the other hand, in the group treated with other drugs that require a large amount of water intake but without tolvaptan or SGLT2 inhibitors, the proportion of deaths was lower (p < 0.01) compared with patients without prescriptions for drugs that require a large amount of water intake. Among patients treated with drugs that require a large amount of water intake, the proportion of in-hospital deaths was higher (9.2% vs 7.6%; p < 0.01) compared with patients without treatment with such drugs.

3.2 Primary and Secondary Endpoints

For the primary endpoint (proportion of patients facing possible dilemma whether to increase or restrict water intake), among 5968 patients who were treated with drugs for which drug package inserts recommended use of a large amount of water intake, 5.4% (n = 320) had a conflicting situation in our study (Table 1). The number of patients with HF, LC, and CKD were 170, 40, and 113, respectively; three patients had more than one of these conditions.

For the secondary endpoint (distribution of 29 defined drugs among patients with HF, LC, or CKD), the four categories of situations identified that required increased water intake as indicated on the package inserts of 29 defined drugs were (1) gastrointestinal-related impairment, (2) renal impairment (including tumor lysis syndrome), (3) dehydration (including reduction of body fluids, perspiration, and hypernatremia), and (4) other (Table 2). Among the 320 patients with diagnoses associated with a likely need for fluid restriction, the most frequently prescribed drugs were tolvaptan (76.9%; 246/320), potassium chloride (14.1%; 45/320), and minocycline (4.1%; 13/320). We found that out of 29 drugs with drug package inserts recommending increased water intake, 15 drugs were administered to patients over 75 years of age with HF, LC, and/or CKD.

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report that a relatively high proportion (5.4%) of patients aged 75 years and older may face the dilemma of having to choose between the recommendation to drink a lot of water together with the administered drug, as stated in the drug package insert, or to follow the recommendation of fluid restriction to control the potential risk of fluid overload associated with their underlying diseases.

In this study, we used data from the health insurance dataset we obtained from JMDC on inpatients aged over 75 years who are covered by the medical care system for elderly in the later stage of life. In Japan, all individuals over 75 years old are incorporated in the medical care system for elderly in the later stage of life and most depend on the universal health insurance system. Patients covered by the medical care system for elderly in the later stage of life have lower co-payment of medical expenses, most of the patients are already retired, and the number of drugs is higher as compared with younger patients. Another reason why we focused on patients over 75 years old is that this is an often used cut-off age for elderly in Japan.

Patients may be at risk for congestion, or fluid overload, potentially resulting in pulmonary edema and worsening of HF, if they have not received adequate information from their prescribers or pharmacists about the appropriate administration of these drugs and possible need to restrict fluid intake despite instructions indicating the opposite in drug package inserts. Three patients in our study were found to have multiple conditions that may require fluid restriction. The presence of multiple discordant conditions (and multiple providers giving different advice to a given patient) may introduce ambiguities and differences in the interpretation of ‘water intake’ among patients and the medical staff [13,14,15,16,17]. This creates more severe problems in patients with complex chronic diseases, especially in those with multiple chronic diseases. Therefore, medical staff are expected to carefully monitor patients’ status when these drugs are administered.

Patients need to be informed about the appropriate amount of liquid to be ingested when taking tablets or capsules orally. In one study, 15.4% of the patients used only up to 60 mL of liquid when taking their tablets or capsules [18]. However, for certain drugs, some of which are listed in Table 2, ingestion of adequate amounts of fluid (e.g., at least 100 mL [19] or 200–250 mL [20] of water) together with intake is recommended to prevent upper gastrointestinal tract damage or to ensure that patients are adequately hydrated. Water requirements are estimated to be about 2.3–2.5 L/day for a population with a low level of daily activity [21]. On the other hand, data indicate that Japanese people consume only 1130 g/day from food and 1100 g/day from drink (total 2200 g/day) [22]. Therefore, the government is conducting educational activities to encourage people to drink an additional 2 cups (about 400 mL) [23]. Older patients are prone to dehydration and emergencies that may result in a visit to the hospital by ambulance because of (1) heat in combination with high humidity, especially in summer; (2) lower feeling of thirst among elderly. In fact, 1316 older patients (86.1% aged 65 years and older) died from heat stroke during summer in 2020 [24]. However, the adequate amount of water intake, especially in older patients with chronic diseases, is not well defined.

In this study, we excluded desmopressin according to the study criteria. However, patients prescribed desmopressin with conditions requiring fluid restriction (severe HF, CKD, LC) or with concomitant medications requiring high fluid intake may have a more serious fluid intake dilemma.

Another example of this potential dilemma is that patients on oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are at risk for drug-induced oesophageal disorders and should consume large amounts of fluids. Because NSAIDs are generally used only for short periods of time, most patients may not need to consider the potential risk of fluid overload due to large water intake with drug. On the other hand, NSAIDs are associated with nephrotoxicity, especially when used chronically, and can cause pre-renal damage and fluid retention, which is a particular risk in patients with impaired renal function. Acetaminophen may be one of the alternative drugs to NSAIDs, because intake of acetaminophen does not need large water intake. Moreover, drugs such as tetracyclines, marketed to treat skin infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections either through oral or intravenous administration in Japan, can be substituted with other antibiotics with different routes of administration to avoid water retention.

Although this study used 2019 practice data and therefore SGLT2 inhibitors were mainly used for diabetic patients, SGLT2 inhibitors have also been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with HF and CKD and are increasingly used for these indications. Because SGLT2 inhibitors are characterized by their positive effects on renal and cardiovascular function, drug modification is difficult for patients with renal or cardiac insufficiency. In addition, tolvaptan, a vasopressin V2-receptor antagonist, is administered for dehydration in HF and LC patients. Tolvaptan is expected to have effects not seen with other diuretics, such as not decreasing renal blood flow and having less effect on the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [9]. Therefore, tolvaptan is more likely to be beneficial in patients with HF and LC and should be used with appropriate fluid and sodium monitoring. Thus, while for drugs such as SGLT2 inhibitors and tolvaptan, which are highly effective in HF, LC, and CKD, increased hydration is recommended based on their pharmacologic actions, these drugs are likely not causing a dilemma. However, excessive water intake should in any case be carefully monitored because of the potential for sodium fluctuations and risk of fluid retention.

5 Limitations

There are some limitations of the present study that should be noted. First, this descriptive survey using a large claims database cannot assess any outcome such as the amount of water intake in each patient and frequency of appropriate instructions and monitoring by the medical staff.

Second, while excessive water intake may lead to complications such as HF and hyponatremia [25] that in extreme cases may possibly cause rhabdomyolysis [26], ‘adequate water intake’ is not defined in the Japanese package insert. The exact wording regarding recommended water intake, for example “a lot of water”, depends on the package insert, but not on the class of drug or the risk of dehydration. Specific indications in individual patients (e.g., regarding risk for pill esophagitis), are left to the responsible physician or pharmacist. The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) published a practical guideline for clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics specifying 1.6 L for daily hydration in older women and 2.0 L for older men [27]. Since the desirable water intake for an individual is context-dependent and differs markedly between individuals depending on their body size, body temperature, physical activity level, and kidney function, a precise quantitative definition of “large amounts of water” could not be made.

Third, our dataset is limited to older patients aged over 75 years. However, it is important to note that there may be differences in the need for and the pattern of drugs requiring abundant fluid intake between patients over and under 75 years old. Further investigation and analysis are needed to explore this aspect.

6 Conclusions

This study shows that 5.4% of patients aged ≥ 75 years may face the dilemma of following advice to restrict fluid intake due to their diagnoses or adhering to instructions in drug package inserts to have abundant fluid intake when taking a drug. Our study raises awareness regarding the dilemma of water restriction and intake in clinical settings, highlighting the importance of considering individual patient needs. These real-world findings emphasize the need for information and guidelines to assist healthcare professionals in navigating this dilemma and making informed decisions for the benefit of their patients.

References

Caraballo C, Desai NR, Mulder H, Alhanti B, Wilson FP, Fiuzat M, et al. Clinical implications of the New York Heart Association classification. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8: e014240.

Goldberg E, Chopra S. Cirrhosis in adults: overview of complications, general management, and prognosis. 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cirrhosis-in-adults-overview-of-complications-general-management-and-prognosis. Accessed 5 Oct 2021.

Marcello T, Natasha W, Bruce C, Andrew H, Chris R, Mei F, Finlay M, et al. Chronic kidney disease and mortality risk: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2034–47.

Katsuhiko N, Takashi T, Norihisa K, Shinya K, Yoshimitsu T, Takeo N. Data resource profile: JMDC claims database sourced from health insurance societies. J Gen Fam Med. 2021;22:118–27.

Central Social Insurance Medical Council. Outline and basic concept of the DPC system (DPC/PDPS). Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2011. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r985200000105vx-att/2r98520000010612.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2022.

Division of the Heath for the Elderly, Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly. Notification No 0403003. Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2006. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r9852000001hi4o-att/2r9852000001hi8n.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2022.

Medical economics division, Health Insurance Bureau. Information on the national health insurance drug price list and generic drugs. Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2022. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2021/04/tp20210401-01.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2022.

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Prescription drug information search. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. 2022. https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuSearch/. Accessed 9 Sep 2021.

Titko T, Perekhoda L, Drapak I, Tsapko Y. Modern trends in diuretics development. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;208: 112855.

Writing Committee Members, Yancy CW, Jessup M, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240-327.

Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646–9.

Japanese Society of Nephrology. Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline for CKD 2018. Japanese Society of Nephrology. 2018. https://cdn.jsn.or.jp/data/CKD2018.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2022.

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24.

Skou ST, Mair FS, Fortin M, Guthrie B, Nunes BP, Miranda JJ, et al. Multimorbidity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:48.

Mohottige D, Manley HJ, Hall RK. Less is more: deprescribing medications in older adults with kidney disease: a review. Kidney. 2021;2:1510–22.

Hall RK. Drawing attention to potentially inappropriate medications for older adults receiving dialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:425–7.

Bowling CB, Vandenberg AE, Phillips LS, McClellan WM, Johnson TM 2nd, Echt KV. Older patients’ perspectives on managing complexity in CKD self-management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:635–43.

Fuchs J. The amount of liquid patients use to take tablets or capsules. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2009;7:170–4.

Jaspersen D. Drug-induced oesophageal disorders: pathogenesis, incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22:237–49.

Tutuian R, Clinical Lead Outpatient Services and Gastrointestinal Function Laboratory. Adverse effects of drugs on the esophagus. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:91–97.

Sawka MN, Cheuvront SN, Carter R 3rd. Human water needs. Nutr Rev. 2005;63:S30-39.

Tani Y, Asakura K, Sasaki S, Hirota N, Notsu A, Todoriki H, et al. The influence of season and air temperature on water intake by food groups in a sample of free-living Japanese adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69:907–13.

“Drink Water for Health” Promotion Committee, Water Supply Division, Pharmaceutical Safety and Environmental Health Bureau, Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare. “Drink water for your health" promotion campaign. 2023. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/topics/bukyoku/kenkou/suido/nomou/index.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2023.

Director-General for Statistics and Information Policy. Annual heat stroke deaths by age group (5-year age group) (1995–2021). Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/tokusyu/necchusho21/index.html. Accessed 18 Mar 2023.

Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water, Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary, Reference Intakes, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate. National Academies Press. 2005. http://nap.nationalacademies.org/10925. Accessed 29 Jan 2022.

Katsarou A, Singh S. Hyponatraemia associated rhabdomyolysis following water intoxication. BMJ Case Rep. 2010;2010:bcr0220102720.

Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Goisser S, Hooper L, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:10–47.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 20K07186.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

KM, TS (Showa University), and JMDC Inc. collaborated on other projects according to the collaborative research agreement. JMDC Inc. did not intervene in data implementation according to the analyzed results of this study. KM received honorarium fees for presentations from JMDC Inc. and Abbvie. TS received an honorarium for presentations at Daiichi Sankyo, NIPRO, Nichi-Iko, Pfizer, Sandoz, Mylan, and Meiji Seika Pharma. BL has been employed by Baxter Healthcare Corporation. However, this funder was not involved in any aspect of this article. The Department of Hospital Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, Showa University received a budget from Ono with a contract research project according to the collaborative research agreement. HK owns shares of Meiji Holdings, Alfresa, Shionogi, Chugai, Eisai, Ono, Rohto, Towa, Daiichi Sankyo, Sawai, FUJIFILM, and Nipro. As a potential conflict of interest, in addition, Hospital Pharmaceutics received a research grant from Daiichi Sankyo, Mochida, Shionogi, Ono, Taiho, and Nippon-kayaku. AM has second-degree relatives who are employed and own shares in Terumo Corp. The other authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Availability of data and material

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics approval

The commercially available JMDC database used in this study contains anonymized processed information based on Japan’s Personal Information Protection Law, and individual informed consent is not required for provision and use. According to the ethical guidelines for clinical research in Japan, research using anonymized processed information is not required to be reviewed by an ethical review committee. Therefore, the use of anonymized data in this study is waived from review by the institutional ethics committee.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE recommendations. In particular, HK and KM contributed to the study conception, drafted the manuscript and collected the raw data. BL revised the manuscript. AW, AM, YK, KT, BL, and TS interpreted the data clinically. All authors took part in the discussions during manuscript preparation. All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koshizuka, H., Momo, K., Watanabe, A. et al. Dilemma Facing Patients Aged 75 Years and Older on Fluid Restriction When Drug Package Inserts Advise Use of a Lot of Water: A Cross-Sectional, Descriptive, and Hypothesis-Generating Study Using a Large Claims Database. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 521–529 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00382-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00382-2