Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic postsurgical pain are commonly prescribed opioids chronically because of refractory pain although chronic opioid use can cause various severe problems.

Objective

We aimed to investigate postoperative chronic opioid use and its association with perioperative pain management in patients who underwent a total knee arthroplasty in a Japanese real-world clinical setting.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using an administrative claims database. We used a multivariate logistic regression analysis to examine the association between perioperative analgesic and anesthesia prescriptions and postoperative chronic opioid use. We calculated all-cause medication and medical costs for each patient.

Results

Of the 23,537,431 patient records, 14,325 patients met the criteria and were included in the analyses. There were 5.4% of patients with postoperative chronic opioid use. Perioperative prescriptions of weak opioids, strong and weak opioids, and the α2δ ligand were significantly associated with postoperative chronic opioid use (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval], 7.22 [3.89, 13.41], 7.97 [5.07, 12.50], and 1.45 [1.13, 1.88], respectively). Perioperative combined prescriptions of general and local anesthesia were also significantly associated with postoperative chronic opioid use (3.37 [2.23, 5.08]). These medications and local anesthesia were more commonly prescribed on the day following surgery, after routinely used medications and general anesthesia were prescribed. The median total direct costs were approximately 1.3-fold higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use than those without postoperative chronic opioid use.

Conclusions

Patients who require supplementary prescription of analgesics for acute postsurgical pain are at high risk of postoperative chronic opioid use and these prescriptions should be given careful consideration to mitigate the patient burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This article describes postoperative chronic opioid use and its association with perioperative pain management in patients undergoing a total knee arthroplasty. |

Our results suggest that patients who require supplementary prescription of analgesics for acute postsurgical pain are at high risk of postoperative chronic opioid use. |

1 Introduction

Chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP), defined as pain that develops after a surgical procedure and persists for at least 3 months after surgery [1, 2], is the most frequent adverse event reported among patients undergoing a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [3]. A TKA is often performed for patients with end-stage or severe osteoarthritis (OA) to improve joint pain and mobility, and is reported to be cost effective when comparing a TKA with non-surgical options [4]. However, approximately 10–40% of patients report CPSP after a TKA [2, 5, 6], and the quality of life in some of these patients is either worsened or unchanged [7]. CPSP is a considerable issue for those affected and could represent a significant social issue in the future, as the rising number of TKAs as a result of the aging Japanese population (e.g., increasing knee and metabolic syndrome) leads to an increase in CPSP [8, 9].

Although opioids are commonly prescribed as an analgesic treatment for CPSP, those patients would be prescribed these long term because of refractory pain [10]. Chronic opioid use has side effects, including opioid endocrinopathy (e.g., sexual dysfunction, decreased energy, and depression) [10] and the development of tolerance, and in some cases, it can lead to abuse, addiction, and death from overdose [10, 11]. In particular, abuse, addiction, and overdose death of opioids are current global issues. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017 estimated that 40.5 million people were opioid dependent and 109,500 people died because of an opioid overdose worldwide [12]. Thus, long-term opioid use should be avoided unless it is specifically required for medical needs. The domestic and international guidelines for knee OA and the use of chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain restrict the prescription of opioids to patients with strong pain or contraindications for other non-opioid analgesics or to patients whose clinical and background characteristics are thoroughly assessed before prescription [13,14,15,16]. Considering those opioid issues, the guidelines, and the Japanese law for opioid prescriptions [17, 18], opioids have been generally restricted to patients who experience pain that cannot be managed by regularly prescribed analgesics (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], acetaminophen) in Japan. A previous study reported that few patients are prescribed opioids to manage CPSP after a TKA in Japan at 3 months or even 6 months after surgery [6]. This previous study aimed to determine the prevalence of CPSP and lacked any further information on opioid use. With limited data available from other studies, the real-world situation of chronic opioid use in Japan remains unknown.

Acute postsurgical pain is one of the risk factors of CPSP among patients who undergo a TKA [5,6,7, 19]; therefore, perioperative pain management can play an important role in alleviating CPSP and reducing postoperative chronic opioid use. We hypothesized that perioperative pain management would be associated with postoperative chronic opioid use in accordance with previous reports and the above-mentioned Japanese medical situations, but little information is available in a Japanese real-world clinical setting. Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the association between perioperative analgesic and anesthesia prescriptions and postoperative chronic opioid use among patients who underwent a TKA in Japan, by using a large-scale database of over 22 million patients to test the above hypothesis. We also exploratively investigated the direct costs among these patients as the information on the economic burden of these patients is scarce in this clinical setting.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using a hospital-based administrative claims database provided by Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). At the time of this study, as of March 2018, the database contained medical information from more than 22 million patients across Japan from 359 facilities, i.e., >20% of all the hospitals that participated in the diagnosis procedure combination (DPC)/per-diem payment system (DPC hospitals, hereafter) [20]. These DPC hospitals are capable of providing acute care for severely ill patients, but are not limited to acute care. The database contained information on demographics (e.g., age and sex) and both inpatient and outpatient claims data, including diagnosis, medical procedures, drug prescriptions, inpatient or outpatient status, and laboratory data.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We extracted the patient data recorded in the database from 1 April, 2008 through 31 March, 2018 (study period). Patients were included if they met all of the following criteria: a diagnosis record of knee OA (the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10, 2013] code: M179) identified during the study period; a TKA record (receipt code: 150050510) identified during the study period after the first diagnosis of OA; and the presence of any records at ≥90 days before the day of the TKA. This look-back period allowed us to examine the patients’ comorbidities.

Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: a record of joint re-replacement surgery (receipt code: 150256110) identified during the study period; a diagnosis record of rheumatoid arthritis (ICD-10 code: M06), malignancy (C00-D09), chronic cardiac failure (I50), or a renal disorder (N04, 10 or 14) identified before the month of TKA; or a diagnosis record of infection (A00-B83) identified during the period of hospitalization. Detailed disease codes for the exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

2.3 Outcomes and Definitions

The primary outcome was the presence or absence of postoperative chronic opioid use. The presence of postoperative chronic opioid use represented a continuous opioid prescription for ≥90 days between 8 and 360 days after the day of surgery, and otherwise an absence of postoperative chronic opioid use. Opioid prescription was identified using the claim prescription codes listed in Table 2 of the ESM. The duration of opioid prescription was calculated as the total number of days covered by the prescriptions, with an allowable gap of 14 days between prescriptions based on the date of prescription and supplied days for each prescription record. An opioid prescription was considered continuous when the gap between the end of the previous opioid prescription and the next opioid prescription was ≤14 days; otherwise, it was considered discontinued. Same days covered under overlapping prescriptions were not double counted. Postoperative chronic opioid use for ≥180 days between 8 and 360 days after the day of surgery was also examined. The secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay in days and the total direct costs in Japanese yen (JPY) (100 JPY = 0.94 US dollar, August 2019) spent by each patient between 8 and 97 days after the day of surgery. The total direct costs refer to all-cause medication and medical costs. Direct costs were categorized for pain-related and pain-unrelated medication, physical therapy, hospital charges, and other. They were further categorized for costs spent during and after hospitalization.

Perioperative prescriptions of analgesics included NSAIDs, opioids, the α2δ ligand, antidepressants, and acetaminophen, and perioperative anesthesia included the general, spinal, epidural, and local types. Opioids were examined separately as weak (e.g., tramadol, codeine) or strong (e.g., morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone), as classified in Japan. We examined all of the above medications, with the exception of general anesthesia, prescribed between a day before and 7 days after the day of surgery (perioperative period). General anesthesia was administered on the day of surgery. The prescriptions were identified using the claims codes listed in Table 2 of the ESM.

The patient background characteristics and perioperative comorbidities considered to influence pain were age, sex, body mass index [7, 21], sleep disorder [ICD-10 code: G47] and mental disorder [F01-99] during hospitalization [7, 21, 22], perioperative sedative use, and complications that cause pain (pain complication) such as lower back pain and neuralgia (Tables 3–4 of the ESM) [22]. Age and body mass index were examined on the day of surgery and on the day of hospital admission, respectively. Comorbidities were examined based on the diagnostic codes recorded in the outpatient or inpatient data in the 3 months prior to the day of surgery.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

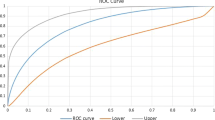

The patient background characteristics and perioperative prescriptions of analgesics and anesthesia were descriptively summarized as appropriate with mean ± standard deviation and median (interquartile range) for the total patients and patients with and without postoperative chronic opioid use. In order to examine the association between perioperative analgesic and anesthesia prescriptions and postoperative chronic opioid use for ≥90 and ≥180 days, we used multivariate logistic regression analyses. The statistical analyses were adjusted for the patient characteristics and preoperative comorbidities described previously, and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. A sensitivity analysis was performed for patients with ≥1 year of follow-up and without pain complications, using the outcome of postoperative chronic opioid use ≥90 days. The timing of the first perioperative analgesics and anesthesia prescribed during the perioperative period was examined using a histogram. The length of the hospital stay and direct costs were calculated for patients overall and separately for patients with and without postoperative chronic opioid use. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS release 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.6.1 (R Core Team, 2019; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3 Results

3.1 Patient Disposition

In total, 23,537,431 patient records were extracted from 1 April, 2008 through 31 March, 2018 (Fig. 1). Among these, 628,927 patients had a diagnosis record of knee OA, 32,156 patients underwent a TKA, and 19,636 patients had the first record ≥90 days before the day of surgery. After excluding 5311 patients who met the exclusion criteria, 14,325 patients comprised the analysis population, among which 770 patients (5.4%) met the criteria for postoperative chronic opioid use and 13,555 patients (94.6%) did not.

3.2 Background Characteristics and Perioperative Prescriptions

The background patient characteristics and perioperative prescriptions of analgesics and anesthesia are summarized in Table 1. The mean age ± standard deviation was 74.8 ± 7.4 years, and female patients comprised 80.5% of the overall analysis population. Age, sex, and body mass index were similar between patients with postoperative chronic opioid use and patients without postoperative chronic opioid use (74.9 ± 7.3 years; 80.5%: 25.7 [23.2–28.4] kg/m2). Preoperative pain complications were found in 38.7% of the overall population and were more prevalent among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (64.8%) than in patients without postoperative chronic opioid use (37.2%).

The most prescribed perioperative analgesics were NSAIDs and strong opioids, and they were prescribed to 13,505 patients (94.3%) and 13,129 patients (91.7%), respectively. The percentage of these prescriptions was similar among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (NSAIDs, 94.8%; strong opioids, 93.9%) and without CPSP (94.2%; 91.5%). However, more patients with postoperative chronic opioid use were prescribed weak opioids (52.6%) and acetaminophen (48.4%) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (weak opioids, 13.9%; acetaminophen, 39.5%).

General anesthesia was prescribed to the majority of the overall population (89.8%), and the least prescribed anesthesia was the local type (1.7%). A similar result was found among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (general, 90.6%; local, 5.2%) and patients without postoperative chronic opioid use (89.7%; 1.5%).

3.3 Association of Perioperative Prescriptions with Postoperative Chronic Opioid Use

Perioperative prescriptions of weak opioids, strong and weak opioids, or the α2δ ligand were significantly associated with postoperative chronic opioid use (adjusted odds ratio [95% CI], 7.22 [3.89, 13.41], 7.97 [5.07, 12.50], and 1.45 [1.13, 1.88], respectively; Table 2). Weak opioids and the α2δ ligand were prescribed more commonly on the day following surgery (43.5% and 32.6%, respectively; Fig. 2). The α2δ ligand was also prescribed to a similarly large proportion of patients (29.6%) on the day before surgery. Other analgesics were not associated with the day following surgery, and all except antidepressants were prescribed first to large proportions of patients on the day of surgery (strong opioid, 99.1%; acetaminophen, 74.8%; NSAIDs, 59.2%). Antidepressants were prescribed commonly a day before and after a TKA (31.7%, 30.2%, respectively).

Prescriptions of general and local anesthesia were significantly associated with postoperative chronic opioid use (3.37 [2.23, 5.08]; Table 2), and local anesthesia was prescribed commonly on the day following surgery (69.5%; Fig. 2). Other types of anesthesia were not associated with postoperative chronic opioid use. Spinal anesthesia was prescribed to the majority of patients on the day of surgery (99.7%), and epidural anesthesia was prescribed to the majority of patients on the day following surgery (93.1%). The results of the statistical analysis were similar to those for ≥1 year of follow-up, postoperative chronic opioid use ≥180 days, and without pain complications (Tables 5–7 of the ESM).

3.4 Hospitalization and Direct Costs

The median (interquartile range) length of hospital stay was 26 [21–33] days in the overall analysis population and was 2 days longer among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (28 [22–40] days) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (26 [21–33] days; Table 3). The median (interquartile range) total direct costs were 574,004 [413,661–896,572] JPY in the overall population and was higher by 171,055 JPY among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (737,562 [492,250–1,310,730] JPY) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (566,507 [407,368–874,118] JPY; Table 3). The pain-related medication costs spent during hospitalization were 4.3-fold higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (8728 [4251–14,777] JPY) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (2035 [650–5135] JPY), with a difference of >6000 JPY. Hospital charges were 1.2-fold higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (365,930 [238,650–718,130] JPY) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (302,290 [206,830–493,210] JPY); these charges were higher by >63,000 JPY.

4 Discussion

In the present study, we found that patients who were prescribed weak opioids, the α2δ ligand, and general and local anesthesia during the perioperative period were more likely to have postoperative chronic opioid use in agreement with our hypothesis. The total direct costs were 574,004 JPY, and the costs were 1.3-fold higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use than those without postoperative chronic opioid use.

The patient characteristics in our study were generally similar to those previously reported populations for TKA in Japan. The mean age of our analysis population was 74.8 years, and the mean age in a previous study for TKA was 72.0 years [6]. Female patients represented 80.5% in our study and approximately 80% in previous reports for TKA in Japan [6, 23, 24].

NSAIDs, strong opioids, and acetaminophen were prescribed to patients primarily on the day of surgery, and weak opioids, the α2δ ligand, and general and local anesthesia associated with postoperative chronic opioid use were commonly administered on the day following surgery. This prescription pattern suggested that acute postsurgical pain in patients with postoperative chronic opioid use was not sufficiently managed by medications (e.g., NSAIDs, strong opioids, and acetaminophen) that were routinely prescribed based on the general clinical pathway for TKA in Japan. In other words, we can speculate that these patients comprise a population who complain of strong pain in the early postoperative phase. Our results suggest that the patients who required additional classes of pain medications were at high risk of postoperative chronic opioid use; this was consistent with previous reports [5,6,7, 19] and our hypothesis. In addition, without a clear consensus on the definite duration of chronic opioid use, we conducted a sensitivity analysis adopting the minimum required period of continuous opioid prescription of ≥180 days. The sensitivity analysis results suggested that perioperative pain medication use and chronic opioid use might be associated with each other, regardless of the defining period of chronic opioid use. Therefore, careful consideration such as the prescription with an opioid exit plan may be required when prescribing opioids to patients at high risk of becoming chronic opioid users. However, other factors contributing to chronic opioid use may exist, including the doses or characteristics of healthcare professionals treating the patients, and thus warrant further comprehensive consideration.

Approximately 5% of our study population was continuously prescribed opioids, and the result was in line with a previous observational study in Japan that reported 3.4% (10 cases out of 298) of patients used opioids at 3 months [6]. Compared to Japan, opioids are more commonly prescribed in North America and Europe where over 94% of the world’s opioids is used [17]. For example, in the USA, more than 40% of patients were continuously prescribed opioids for 90–180 days after a TKA [25]. The low opioid prescription in Japan is partly owing to healthcare systems, regulations, and historical issues. For example, the Japanese healthcare insurance system does not cover oxycodone for non-cancer pain [18]. In addition, strict prescription restriction and storage rules under the Narcotics and Psychotropic Control Law apply to opioids [18]. However, patients who are continuously prescribed opioids should be closely monitored because of potentially serious side effects, although the chronic opioid prescription rate was low in the present and previous studies [6]. Therefore, for patients who require long-term opioid use, multimodal analgesia may be a better option. The combination of opioid and non-opioid analgesics is recommended for the opioid-sparing effect and the pre-emptive approach to pain management in patients undergoing a knee or hip arthroplasty [26, 27].

The median total direct costs were 1.3-fold higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use (737,562 JPY) than those without postoperative chronic opioid use (566,507 JPY). Furthermore, the direct costs of all categories were higher among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use than those without postoperative chronic opioid use, and postoperative chronic opioid use appeared to increase the overall direct costs. Among the cost categories, hospital charges of patients with postoperative chronic opioid use were particularly higher than those without postoperative chronic opioid use, with a difference of >63,000 JPY. As the median length of hospital stay was 2 days longer among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use, hospital charges were one of the largest contributing factors to the higher costs spent among patients with postoperative chronic opioid use.

4.1 Limitations

The main strength of this study is its large sample size; however, the study also has several limitations. First, our results may not be generalizable to the entire population undergoing a TKA in Japan because the database contained patient records from hospitals using the DPC/per-diem payment system but did not contain data from clinics or institutions not using the DPC/per-diem payment system. Nonetheless, the database covered over 20% of DPC hospitals across Japan as of 2018, and most cases of TKA in Japan are performed in DPC hospitals. Second, although we found an association between perioperative prescriptions of some medications and postoperative chronic opioid use, it is unclear whether the relationship is causal. In addition, as the present study is observational, we have to consider the existence of unmeasured confounding factors. Although we adjusted for measurable confounding factors in the logistic regression models (e.g., sex, age, perioperative comorbidities that influence pain), it might be insufficient. For example, we adjusted for mental disorders as one of the confounding factors but not for each disorder or the use of specific drugs used for these disorders. Further studies that overcome these limitations are needed to conclude the relationship is causal. Third, a link between opioid prescription and knee pain was assumed in the present study because the database does not give such detailed information, which means that such a link does not always exist. In order to mitigate this limitation, the logistic regression models were adjusted for complications that can cause pain and performed among a population without complications as a sensitivity analysis. Similarly, the costs spent for knee pain and a TKA could not be isolated from the costs spent for other clinical conditions. Therefore, we restricted our analysis to costs spent between 8 and 97 days after a TKA in an attempt to examine the costs associated with pain and a TKA. However, this duration may be insufficient. Fourth, limitations inherent to retrospective studies using hospital-based health claims, such as misdiagnosis, misrecording, and missing records, apply to this study.

5 Conclusions

Among patients who underwent a TKA in Japan, perioperative use of weak opioids, the α2δ ligand, and general and local anesthesia were associated with postoperative chronic opioid use. These medications were prescribed primarily on the following day of a TKA. These results suggested that patients who require supplementary prescription of analgesics for acute postsurgical pain are at high risk of postoperative chronic opioid use. In addition, patients with postoperative chronic opioid use had higher direct costs. Therefore, particular attention, such as prescriptions with opioid exit plans, may be required when administering opioids to these patients.

References

Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160:19–27.

Schug SA, Lavandʼhomme P, Barke A, The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain. Pain. 2019;160:45–52.

Gagnier JJ, Morgenstern H, Kellam P. A retrospective cohort study of adverse events in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery. Patient Saf Surg. 2017;11:15.

Kamaruzaman H, Kinghorn P, Oppong R. Cost-effectiveness of surgical interventions for the management of osteoarthritis: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:183.

Thomazeau J, Rouquette A, Martinez V, et al. Predictive factors of chronic post-surgical pain at 6 months following knee replacement: influence of postoperative pain trajectory and genetics. Pain Physician. 2016;19:E729–41.

Sugiyama Y, Iida H, Amaya F, et al. Prevalence of chronic postsurgical pain after thoracotomy and total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective multicenter study in Japan (Japanese Study Group of Subacute Postoperative Pain). J Anesth. 2018;32:434–8.

Bugada D, Allegri M, Gemma M, et al. Effects of anaesthesia and analgesia on long-term outcome after total knee replacement: a prospective, observational, multicentre study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2017;34:665–72.

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, et al. Accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance raises the risk of occurrence and progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2012;20:1217–26.

Kawata M, Sasabuchi Y, Inui H, et al. Annual trends in knee arthroplasty and tibial osteotomy: analysis of a national database in Japan. Knee. 2017;24:1198–205.

Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S105–20.

Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445–52.

Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019;394:1560–79.

Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI Recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2008;16:137–62.

Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, for American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113–30.

The Japanese Orthopaedic Association. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines adapted to Japanese by Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) Committee on clinical practice guideline on the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Research Society International 2012. (Japanese).

The Committee for the Guidelines for Prescribing Opioid Analgesics for Chronic Non-cancer Pain of Japan Society of Pain Clinicians (JSPC). Guidelines for Prescribing Opioid Analgesics for Chronic Non-cancer Pain. Tokyo: Shinko Trading Co Ltd; 2017. (Japanese).

Berterame S, Erthal J, Thomas J, et al. Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: A worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet. 2016;387:1644–56.

Onishi E, Kobayashi T, Dexter E, et al. Comparison of opioid prescribing patterns in the united states and Japan: Primary care physicians’ attitudes and perceptions. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:248–54.

Buvanendran A, Della Valle CJ, Kroin JS, et al. Acute postoperative pain is an independent predictor of chronic postsurgical pain following total knee arthroplasty at 6 months: a prospective cohort study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;44: e100036.

Medical Data Vision (MDV). Press release: Overview of claims database in March 2018; 2018. https://www.mdv.co.jp/press/2018/detail_953.html. Accessed 30 Sep 2022 (Japanese).

Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ, et al. Predictors of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:551–61.

Namba RS, Singh A, Paxton EW, et al. Patient factors associated with prolonged postoperative opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2449–54.

The Japan Arthroplasty Register. TKA/UKA/PFA Registry Statistics: February 2006 to March 2018. The Japan Society for Replacement Arthroplasty; 2018. (Japanese).

The Japan Arthroplasty Register. 2017 Annual Report. The Japan Society for Replacement Arthroplasty; 2018. https://jsra.info/pdf/JAR%202017%20Annual%20Report.pdf. Accessed 9 Aug 2019. (Japanese).

Namba RS, Inacio MCS, Pratt NL, et al. Persistent opioid use following total knee arthroplasty: a signal for close surveillance. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:331–6.

Golladay GJ, Balch KR, Dalury DF, Satpathy J, Jiranek WA. Oral multimodal analgesia for total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:S69-73.

Malan TP Jr, Marsh G, Hakki SI, Grossman E, Traylor L, Hubbard RC. Parecoxib sodium, a parenteral cyclooxygenase 2 selective inhibitor, improves morphine analgesia and is opioid-sparing following total hip arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:950–6.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Japan Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KN contributed to the concept and design of the study, data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. YL contributed to the concept and design of the study, data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. NE contributed to the concept and design of the study and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. RW contributed to the design of the study, data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. TU contributed to the concept and design of the study, data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. MD contributed to the concept and design of the study data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. SK contributed to the concept and design of the study, data analysis or acquisition, and data interpretation and development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

Kazutaka Nozawa was an employee of Pfizer Japan, Inc. during the conduct of the study and manuscript development, and is an employee of Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan, Inc. at the time of submission. Nozomi Ebata is an employee of Pfizer Japan, Inc. Ryozo Wakabayashi is an employee of Clinical Study Support, Inc. Yingsong Lin, Takahiro Ushida, Masataka Deie, and Shogo Kikuchi were not financially compensated for their collaboration in this project or for the development of this manuscript; however, Takahiro Ushida has received an honorarium from Pfizer Japan Inc. outside of this work. The authors have no other conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics Approval

This study did not require patient consent or approval from an institutional review board and independent ethics committee because the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects do not apply to studies that exclusively use de-identified data. Nonetheless, the ethics committee at Aichi Medical University was consulted, and the committee decided evaluation by the committee was unnecessary. This study was conducted in accordance with guidelines including the Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (Revision 3) issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The dataset that supports the findings of this study are available from Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), a commercial database provider. The dataset analyzed for this study cannot be shared publicly because of contractual agreements between Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. and medical facilities. For inquiries regarding access to the dataset used in this study, please contact Medical Data Vision Co., Ltd. (https://www.mdv.co.jp/).

Code availability

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nozawa, K., Lin, Y., Ebata, N. et al. Perioperative Analgesics and Anesthesia as Risk Factors for Postoperative Chronic Opioid Use in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Retrospective Cohort Study Using Japanese Hospital Claims Data. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 10, 331–340 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00363-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-023-00363-5