Abstract

Background

There is a risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring from exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy.

Objective

This study was performed to systematically review the available evidence regarding the impact of in utero exposure to antidepressants on motor and intellectual disability outcomes in children.

Patients and Methods

A systematic literature search for published observational studies examining the effects of antidepressants on motor development or intellectual disabilities in children was conducted using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed/Medline, and Google Scholar.

Results

A total of 14 studies were included in this review. Studies have reported conflicting effects on motor development in infants with maternal exposure to antidepressants. Furthermore, not all of the studies included that assessed intellectual disabilities in infants found an association between maternal exposure to antidepressants and intellectual disabilities. However, methodological flaws existed in the studies, such as the use of scales with inadequate reliability or validity, a lack of statistical power, or confounding by indication or disease severity.

Conclusion

The available literature provides inconclusive evidence on the relationship between in utero exposure to antidepressants and adverse effects on motor development outcomes or neurocognitive skills. Further observational studies with robust methodologies are needed to comprehensively evaluate the potential risks of prescribing antidepressants during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The available evidence on the association between antidepressant use during pregnancy and poor motor development in offspring is inconclusive. |

The results of the reviewed studies do not suggest an association between in utero exposure to antidepressants and delayed adverse effects on intellectual ability in children. |

1 Introduction

Maternal depression encompasses mild and severe non-psychotic depressive conditions affecting pregnant women and new mothers. It includes depressive episodes that occur during pregnancy and up to a year after childbirth [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 10% of pregnant women and 13% of new mothers (up to 12 months postpartum) experience depression [3]. The growing incidence of maternal depression imposes a substantial social and economic burden on many societies; hence, it is now recognized as a global public health issue [4].

Untreated maternal depression is associated with higher rates of pregnancy-related complications, such as premature death of the infant, and poor fetal outcomes, such as low fetal growth and increased fetal heart rate [5, 6]. Untreated depression during pregnancy is also associated with a higher risk of preterm birth (< 37 weeks) and lower birth weight (< 2500 g) than in women without depression [7]. Furthermore, having depression during pregnancy is associated with a broad range of neurodevelopmental problems in offspring, such as negative behavioral, emotional, or cognitive outcomes, intellectual disabilities, and language impairment [8,9,10,11]. Observational studies have shown that persistent depression during pregnancy is associated with increased risk of delayed cognitive and behavioral development in children and with antisocial and violent behavior in teenagers [8, 9], which emphasizes the importance of adequate maternal depression treatment during pregnancy to prevent severe adverse outcomes for mother and child.

Despite the need for appropriate treatment of maternal depression during pregnancy, there is limited information available to guide clinicians [12]. The prevalence of antidepressant use during pregnancy worldwide varies from 1.8 to 7.3% [13,14,15]. Currently, a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is the most common treatment for moderate to severe maternal depression, while psychotherapy alone is recommended in mild cases [16,17,18]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most commonly used antidepressants during pregnancy [16,17,18]. However, antidepressants have their own set of adverse effects on maternal and fetal outcomes. Since they can pass the placental barrier, their use during pregnancy may potentially affect the neurotransmitter systems in the brain of the offspring, and may eventually influence neurodevelopmental outcomes [19]. Consequently, clinicians often face the risk–benefit dilemma of whether to treat mothers with antidepressants during pregnancy. There is a need for a systematic examination of the published literature to provide evidence on the use of antidepressants during pregnancy and on the potential risk of neurodevelopmental outcomes in the offspring.

Studies assessing the safety of antidepressant use during pregnancy report conflicting results [12, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. For example, several studies have linked prenatal exposure to antidepressants to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism spectrum disorder in children [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 31,32,33,34,35]. However, after addressing confounding bias through sibling design, the risk was moved to the null finding [33,34,35]. On the other hand, only a few studies have examined the potential impact of antidepressant use on other neurodevelopment aspects, such as cognitive and motor development, intelligence quotient (IQ), or language competence [12, 29, 36,37,38], and there is no consensus on the effect of prenatal exposure to antidepressants on motor and intellectual development in offspring [12, 29, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Therefore, this systematic review aims to evaluate the available literature concerning the prenatal use of antidepressants and its potential impact on motor and intellectual development in offspring.

2 Methodology

2.1 Data Sources

A systematic literature search for the papers published before December 2020 was performed in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed/Medline, and Google Scholar. The reference lists of the selected articles and the systematic reviews/meta-analyses identified through the search were also screened for additional publications.

2.2 Search Terms

Medical subject headings combined with relevant keywords were used to search the databases. The search terms for motor outcomes were “antidepressant” OR “tricyclic antidepressants” OR “TCA(s)” OR “selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors” OR “SSRI(s)” OR “serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors” OR “SNRI(s)” AND “children” OR “offspring” OR “pregnancy” OR “pregnant” OR “maternal” OR “prenatal” OR “antenatal” OR “gestational” AND “motor performance” OR “neuromotor performance” OR “motor activity” OR “motor skills” OR “motor outcome.”

For intellectual disabilities, the search terms were “antidepressant” OR “tricyclic antidepressants” OR “TCA(s)” OR “selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors” OR “SSRI(s)” OR “serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors” OR “SNRI(s)” AND “children” OR “offspring” OR “pregnancy” OR “pregnant” OR “maternal” OR “prenatal” OR “antenatal” OR “gestational” AND cognitive” OR “cognitive development” OR “intelligence” OR “intelligence quotient (IQ)” OR “low IQ” OR “intellectual development disorder” OR “intellectual disability” OR “mental retardation” OR “mental deficiency.”

2.3 Inclusion Criteria

We included papers that met the following criteria. The study population was children, between 0 and 18 years old, of mothers exposed to antidepressants during pregnancy. The exposure window was from 30 days before conception to the time of delivery. The exposure of interest was the mother’s use of antidepressants, including SSRIs, serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). We studied the transient effects of prenatal exposure to antidepressants on motor or intellectual development events that had been assessed either by medical diagnoses or by standardized psychometric instruments.

2.4 Selection of Studies

The initial search was limited to human studies published in English. The titles and abstracts of all articles found in the initial search were screened for primary evaluation. Only observational studies (cohort, case–control design, or their variants) available in full text were included. Two reviewers independently conducted the systematic literature search, screening, and reviewing of articles. Upon completion of the literature search, both reviewers shared their findings and reached a consensus for the final study selection. The current review adheres to the guidelines and checklist of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

2.5 Quality Appraisal

Once the selection process was complete, the baseline characteristics of all studies included (i.e., first author’s name, date of publication, study design, sample size, duration of antidepressant exposure, outcome measure, children’s age, and adjusted variables) were carefully examined. The methodological quality and risk of bias for each study were assessed using the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies (ROBINS-I) tool (Table 4).

3 Results

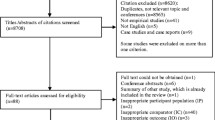

The initial literature search resulted in 813 articles. After excluding duplicates, non-English studies, and animal studies, 670 records were screened. Of these, 626 records were excluded after title/abstract screening. In total, 44 articles remained for full-text screening. Thirty articles were subsequently excluded: 20 for addressing other outcomes and ten for being reviews. Finally, 14 studies remained for use in this systematic review. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for article selection based on PRISMA. Tables 1 and 2 present the baseline characteristics and main findings of the studies included.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection. PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

3.1 Motor Development

3.1.1 Characteristics of the Studies Included

Ten studies examined the association between antidepressant use during pregnancy and poor motor development outcomes in offspring [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. The studies operationalized adverse motor development outcomes using an observer assessment scale or diagnostic codes (Table 1). Seven studies used psychometric evaluation instruments; six studies [40,41,42, 44, 47, 48] used either the 2nd or 3rd edition of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID-II and BSID-III), and one study used the Movement Assessment Battery for Children (Movement ABC) [45]. All psychometric evaluations were conducted by trained psychologists or occupational therapists who were blinded to the infants’ exposure status. Two studies assessed motor activity in infants by observing the infants physically with activity monitoring devices and the Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) [39, 46]. Physical observations were done by trained assessors who were blinded to the infants’ exposure status. One study based its outcome assessment on medical diagnosis by physicians in specialized care units [43].

3.1.2 Antidepressant Exposure

Antidepressant exposure was ascertained from self-reported questionnaires in five studies [39, 44, 45, 47, 48], while the remaining studies obtained exposure status from medical records. Most studies (six out of nine) specifically examined the association between maternal exposure to SSRIs and adverse effects on motor outcomes [39, 41, 43, 46, 48]. The timing of antidepressant exposure during pregnancy varied between studies, and only four studies classified antidepressant exposure by trimester [39, 44, 47, 48].

3.1.3 Bayley Scales of Infant Development

Using BSID-II or BSID-III, one study showed that the fine motor function performance in offspring of healthy mothers unexposed to antidepressants was 9.4% higher than that in exposed children [42]. However, these findings were not statistically significant (Table 1). In contrast, three studies showed a statistically insignificant higher score (ranging from 0.9 to 6.1%) in fine motor functions in offspring with in utero exposure to antidepressants in comparison to offspring of unexposed healthy mothers [40, 41, 44]. Notably, none of the studies considered the cumulative in utero exposure to antidepressants, nor the timing of the exposure by trimester (except one study). Casper et al. (2011) did link longer antidepressant use during pregnancy to adverse effects on motor development in offspring [47]. However, this study did not include a control group of unmedicated women with depression; therefore, confounding by indication cannot be ruled out.

Three studies showed that the score of gross motor function performance was 9.1–12.6% lower in children with in utero exposure to antidepressants in comparison to offspring of unexposed healthy mothers [40, 42, 48]. On the other hand, two studies demonstrated slightly higher scores (1.1–7.7%) in gross motor function in children with in utero exposure to antidepressants in comparison to unexposed children of healthy mothers [41, 44].

3.1.4 Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale

Two small studies examined the association of in utero antidepressant exposure with early motor development using NBAS and reported inconsistent findings. Zeskind and Stephens showed worse motor performance during sleep associated with in utero exposure to antidepressant (unspecified by trimester) in comparison to no exposure with healthy mothers [46]. Similarly, there was an association between maternal exposure to antidepressant during the third trimester and adverse motor outcomes in neonates in another study [39]. However, these differences in motor activity were no longer significant when adjusted for gestational age in both studies [39, 46].

3.1.5 Movement Assessment Battery for Children

One study reported insignificant worse motor development effects (using the Movement ABC test) in offspring following antidepressant exposure during pregnancy in comparison to those born to healthy mothers with no antidepressant use [45]. The composite motor score was 3.6% lower in children with maternal exposure to antidepressants in comparison to those without exposure to antidepressant.

3.1.6 Diagnoses of Motor Disorders

Brown et al. (2016) [43] conducted a large population-based study using data on singleton live births from the Finnish Medical Birth Register using medical diagnoses as the measure of motor outcome. No significant differences were observed in motor outcomes between offspring in the antidepressant-exposed group and in the unmedicated group with mothers who had depression (hazard ratio [HR] 1.18; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.81–1.72). The authors observed an insignificant increased risk of motor disorders in offspring of mothers with at least two antidepressant purchases compared to offspring of unexposed healthy mothers (HR 1.26; 95% CI 0.9–1.77). The risk increased with more refills of SSRI prescriptions (≥ 2) compared to only receiving one prescription; this might indicate confounding by depression severity, which the authors attempted to control for by adjusting for suicidal ideation and restricting the analysis to those with no other psychotropic agents [43].

3.1.7 Confounding Domains Assessed by the Included Studies

Table 3 shows the covariates evaluated by the studies included. Two potential confounders (maternal age and gestational age) were evaluated in all studies. Other variables controlled for in some studies including cigarette and alcohol use during pregnancy, the mother’s education level, the mother’s socioeconomic status, the mother’s IQ, and the duration of antidepressant exposure (Table 3). Nine out of ten studies assessed either the severity of the maternal depression or the maternal psychiatric history. Zeskind and Stephens’s study [46] was the only one that did not evaluate maternal depression or psychiatric comorbidity during pregnancy. The study mainly included postpartum mothers and was limited to measures of maternal treatment intensity in terms of number and duration of antidepressant use during pregnancy [46].

3.1.8 Risk of Bias

Of the ten studies assessing motor development as an outcome of maternal exposure to antidepressants, we considered nine studies [39,40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48] at moderate risk of bias and one study [44] at serious risk of bias (Table 4).

3.2 Intellectual Disabilities

3.2.1 Characteristics of the Studies Included

Five studies [45, 49,50,51,52] examined the association between maternal antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and the risk of intellectual disabilities in offspring. The studies used a psychometric instrument (BSID-II) and the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities [49, 50], the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) [45, 51], or diagnostic codes [52]. The psychometric assessment was done by trained psychologists or occupational therapists blinded to the offspring’s exposure status.

3.2.2 Antidepressant Exposure

In four studies, antidepressant exposure ascertainment was done through self-reported questionnaires [45, 49,50,51]. Maternal antidepressant exposure windows were specified in two studies, where the use of antidepressants went on throughout the pregnancy, starting from the first trimester, and this was a requirement for eligibility for the study [45, 50]. The other two studies did not restrict the timing or length of antidepressant use [49, 51, 52]. Most studies (three out of five) specifically examined the association between maternal exposure to SSRIs and adverse effects on intellectual performance outcomes [49, 50, 52].

3.2.3 Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence

Two studies used the WPPSI to examine the association between exposure to antidepressants during the entire pregnancy and detrimental effects on intellectual ability [45, 51]. In one study, the full IQ test score was similar between children exposed to antidepressants and unexposed children of healthy mothers (mean IQ score ± SD = 115 ± 14 vs. 115 ± 8; p = 0.92) [45]. The other study reported slightly higher full IQ scores (IQ = 112 ± 11) in unexposed children of healthy mothers than in antidepressant-exposed children (IQ = 105 ± 13) [51]. However, neither study found a statistically significant association between in utero exposure to antidepressants and adverse mental outcomes.

3.2.4 Bayley Scales of Infant Development and McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities

The McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities and the BSID were used in two studies to assess the risk of adverse effects on a child’s intellectual abilities following in utero exposure to antidepressants [49, 50]. Both studies included only mothers who used antidepressants throughout the pregnancy, starting from the first trimester. The performance in global IQ assessments was similar or slightly higher in exposed children compared to unexposed children of healthy mothers (Table 2). The results of global cognitive function assessments were comparable between exposed children and unexposed children of healthy mothers (Table 2). In both studies, there was no association between in utero exposure to antidepressants and adverse effects on the offspring’s cognitive development or intellectual ability compared to no exposure [49, 50].

3.2.5 Intellectual Disabilities Diagnosis

Viktorin et al. [52] used the Swedish national registers to conduct a retrospective cohort study comprising 179,007 infants. Infants exposed to antidepressants through their mother had a 33% higher risk of intellectual disability compared to unexposed infants of healthy mothers. However, the results were not statistically significant (relative risk 1.33; 95% CI 0.90–1.98) [52]. The specific timing of exposure to antidepressants and the length of exposure did not have an effect on the association between antidepressant exposure and intellectual disabilities in infants (Table 2).

3.2.6 Confounding Domains Assessed by the Studies Included

Table 3 highlights the covariates evaluated by the studies included that examined intellectual disabilities as an outcome. The maternal age and gestational age were evaluated by all studies. Covariates such as cigarette and alcohol use during pregnancy, the mother’s education level, the mother’s socioeconomic status, the mother’s IQ, and the duration of antidepressant exposure were considered in the studies (Table 3). Adjustment for the use of psychotropic drugs other than antidepressants occurred in three studies [50,51,52].

3.2.7 Risk of Bias

Of the five studies [45, 49,50,51,52] that examined the association between maternal antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and the risk of intellectual disabilities in offspring, we assessed two studies [51, 52] at low risk of bias, two at moderate risk of bias [45, 50], and one at serious risk of bias [49].

4 Discussion

This systematic review was conducted to examine published studies investigating the relationship between in utero exposure to antidepressants and the risk of poor motor development and intellectual disability outcomes in offspring.

The available evidence concerning the association between antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of adverse motor development is inconsistent. A recently published meta-analysis [30] reported a small effect (effect size = 0.22; 95% CI 0.07–0.37) in the direction of an increased risk of worse motor development outcomes in children exposed to antidepressants. However, given the marked variations in outcome measurements among the studies, particularly in methods used to quantify motor performance, the meta-analysis is subject to a moderate degree of heterogeneity (I2 = 56.6%; p = 0.002). Although the study suggested a possible association between in utero exposure to antidepressants and delayed motor development, it could not rule out the influence of different biases or of unmeasured confounding such as confounding by indication.

The results of the observational studies included found no association between antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and intellectual disability outcomes in offspring [45, 49,50,51,52]. Nulman et al. conducted a series of studies [49,50,51] to examine the differences in IQ between antidepressant-exposed and unexposed children, and found no significant association between intellectual disabilities and prenatal exposure to antidepressants. Methodologically, Nulman et al. [50] mitigated the concerns of a previous study [49] by the same authors about exposure misclassification in the first trimester by restricting the study cohorts to women who had used antidepressants throughout their pregnancy. In addition, Nulman et al.’s 2012 study [51] had fewer limitations than their previous studies [49, 50] and was assessed to be at low risk of bias using the ROBINS-I tool. This study overcame confounding by indication by including a control group of depressed mothers who did not receive antidepressants [51].

The findings summarized in this systematic review should be interpreted with caution given the many methodological limitations inherent to the observational studies included. The main problem that limits the validity of most studies is unmeasured confounding, particularly confounding by indication. In only two of the 14 studies, the researchers had an appropriate comparison group of untreated, depressed mothers to address confounding by indication [43, 51]. The risk of residual confounding is another major concern, as these studies had variation in the type of covariates adjusted or controlled for, and most studies did not control for several potential confounders in the analysis, such as the use of psychotropic drugs other than antidepressants, maternal and paternal psychiatric history, or other environmental or genetic factors. Only one study, by Brown et al. [43], controlled for maternal and paternal history of psychiatric diagnoses through matching siblings with discordant exposure status. Notably, sibling design may address time-invariant or shared confounders but may fail to address time-varying confounders. In comparison to non-sibling design, the risk of bias is higher in sibling design studies when the levels of confounders differ between the siblings [53].

Furthermore, the methods used to assess motor performance, intellectual disabilities, and the severity of the maternal depression varied greatly across studies in terms of validity and internal consistency. The BSID was the most commonly used scale for motor assessment in most studies. Other methods included the NBAS and Movement ABC. Of these, only Movement ABC is a neuropsychological test specifically for motor function impairment and has been reported to have high test–retest reliability and moderate construct validity [54] It was used in one study [45]. In contrast, although the BSID is regarded as the gold standard assessment tool for measuring the developmental functioning of infants and toddlers, its motor subscale is considered a poor predictor of later motor impairments [55].

Measures used to assess intellectual disability outcomes included the WPPSI-III, the Bayley Mental Development Index, and the McCarthy General Cognitive Index. Only the WPPSI-III is a scale specifically designed to provide a full-scale IQ score on general intellectual ability [56]. On the other hand, the type and severity of depression was assessed using a variety of scales, such as the self-rated Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, the Index of Parental Attitudes, the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale, the clinician-rated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and many more. In the studies included, these scales were used either individually or in combination. Taken together, the diverse range of assessment scales and their lack of validity made the results of the studies difficult to compare.

The ascertainment of the timing and duration of the prenatal exposure to antidepressants also differed greatly between studies, leading to exposure misclassification. Because of this, we could not find conclusive evidence on the association between maternal antidepressant exposure and adverse motor or intellectual effects in offspring. The studies used different methods to collect information about antidepressant use during pregnancy, including electronic medical registry data, medical record review, and self-report; however, no study reported adherence in drug use. Hence, there is uncertainty regarding the actual use of the prescribed antidepressants.

5 Conclusion

The studies reviewed were inconclusive in their findings concerning the motor and cognitive neurodevelopmental effects of in utero antidepressant exposure. Furthermore, several methodological limitations, such as confounding by indication and a lack of adjustment for potential confounders, existed in the reviewed studies. Therefore, future studies should use a more robust methodology to help clinicians make better informed risk–benefit assessments concerning the use of antidepressants during pregnancy.

References

Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. Perinatal depression: prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary. In: AHRQ evidence report summaries 1998–2005. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2005. p. 119. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11838/.

Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis C-L, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1775–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9.

World Health Organization. Maternal mental health. 2019. https://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/. Accessed 4 Mar 2019.

World Health Organization. Women’s mental health: an evidence-based review. Geneva: WHO Press; 2000.

Gentile S. Untreated depression during pregnancy: Short-and long-term effects in offspring. A systematic review. Neuroscience. 2017;342:154–66.

Wisner KL, Sit DK, Hanusa BH, Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen DL, Hunker DF, Perel JM, Jones-Ivy S, et al. Major depression and antidepressant treatment: impact on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:557–66.

Jarde A, Morais M, Kingston D, et al. Neonatal outcomes in women with untreated antenatal sepression compared with women without depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(8):826–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0934.

Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, Emond A. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2008;115:1043–51.

Hay DF, Pawlby S, Waters CS, Perra O, Sharp D. Mothers’ antenatal depression and their children’s antisocial outcomes. Child Dev. 2010;81:149–65.

Hay DF, Pawlby S, Waters CS, Sharp D. Antepartum and postpartum exposure to maternal depression: different effects on different adolescent outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:1079–88.

Tuovinen S, Lahti-Pulkkinen M, Girchenko P, Lipsanen J, Lahti J, Heinonen K, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy and child developmental milestones. Depression Anxiety. 2018;35:732–41.

El Marroun H, White T, Verhulst FC, Tiemeier H. Maternal use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medication during pregnancy and childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:973–92.

Bérard A, Zhao J-P, Sheehy O. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations in a cohort of depressed pregnant women: an updated analysis of the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013372.

Jimenez-Solem E. Exposure to antidepressants during pregnancy: prevalences and outcomes. Dan Med J. 2014;61(9):B4916.

Zoega H, Kieler H, Nørgaard M, et al. Use of SSRI and SNRI Antidepressants during pregnancy: a population-based study from Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144474. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0144474.

Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA. Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:544-e1.

Altshuler LL, Cohen LS, Moline ML, et al. The expert consensus guideline series. Treatment of depression in women. Postgrad Med. 2001;(Spec. No.):1–107.

Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):703–13.

Rampono J, Simmer K, Ilett KF, Hackett LP, Doherty DA, Elliot R, Kok CH, Coenen A, Forman T. Placental transfer of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants and effects on the neonate. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42:95–100.

Uguz F. Maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: a systematic review of the current literature. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38:254–9.

Zhou XH, Li YJ, Ou JJ, Li YM. Association between maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Molecular Autism. 2018;9:21.

Morales DR, Slattery J, Evans S, Kurz X. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: systematic review of observational studies and methodological considerations. BMC Med. 2018;16:6.

Mezzacappa A, Lasica PA, Gianfagna F, Cazas O, Hardy P, Falissard B, Sutter-Dallay AL, Gressier F. Risk for autism spectrum disorders according to period of prenatal antidepressant exposure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:555–63.

Man KK, Tong HH, Wong LY, Chan EW, Simonoff E, Wong IC. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy and risk of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:82–9.

Andalib S, Emamhadi MR, Yousefzadeh-Chabok S, Shakouri SK, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Vafaee MS, Michel TM. Maternal SSRI exposure increases the risk of autistic offspring: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:161–6.

Kobayashi T, Matsuyama T, Takeuchi M, Ito S. Autism spectrum disorder and prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;65:170–8.

Kaplan YC, Keskin-Arslan E, Acar S, Sozmen K. Prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;66:31–43.

Prady SL, Hanlon I, Fraser LK, Mikocka-Walus A. A systematic review of maternal antidepressants use in pregnancy and short-and long-term offspring’s outcomes. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2018;21(2):127–40.

Gentile S, Galbally M. Prenatal exposure to antidepressant medications and neurodevelopmental outcomes: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2011;128:1–9.

Grove K, Lewis AJ, Galbally M. Prenatal antidepressant exposure and child motor development: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2018;142:e20180356.

Clements CC, Castro VM, Blumenthal SR, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure is associated with risk for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder but not autism spectrum disorder in a large health system. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(6):727–34.

Castro VM, Kong SW, Clements CC, et al. Absence of evidence for increase in risk for autism or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder following antidepressant exposure during pregnancy: a replication study. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:708.

Sujan AC, Rickert ME, Öberg AS, et al. Associations of maternal antidepressant use during the first trimester of pregnancy with preterm birth, small for gestational age, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1553–62.

Brown HK, Ray JG, Wilton AS, et al. Association between serotonergic antidepressant use during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorder in children. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1544–52.

Man KKC, Chan EW, Ip P. Prenatal antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: population-based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2350.

Hjorth S, Bromley R, Ystrom E, Lupattelli A, Spigset O, Nordeng H. Use and validity of child neurodevelopment outcome measures in studies on prenatal exposure to psychotropic and analgesic medications: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(7):e0219778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219778.

Loebstein R, Koren G. Pregnancy outcome and neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to psychoactive drugs: The Motherisk experience. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1997;22(3):192–6.

de Araujo JSA, Delgado IF, Paumgartten FJR. Antenatal exposure to antidepressant drugs and the risk of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Cad Saude Publica. 2020;36(2):e00026619. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00026619.

Smith MV, Sung A, Shah B, Mayes L, Klein DS, Yonkers KA. Neurobehavioral assessment of infants born at term and in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Early Human Dev. 2013;89:81–6.

Hanley GE, Brain U, Oberlander TF. Infant developmental outcomes following prenatal exposure to antidepressants, and maternal depressed mood and positive affect. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:519–24.

Casper RC, Fleisher BE, Lee-Ancajas JC, Gilles A, Gaylor E, DeBattista A, Hoyme HE. Follow-up of children of depressed mothers exposed or not exposed to antidepressant drugs during pregnancy. J Pediatr. 2003;142:402–8.

Galbally M, Lewis AJ, Buist A. Developmental outcomes of children exposed to antidepressants in pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:393–9.

Brown AS, Gyllenberg D, Malm H, McKeague IW, Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S, Artama M, et al. Association of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure during pregnancy with speech, scholastic, and motor disorders in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:1163–70.

Austin MP, Karatas JC, Mishra P, Christl B, Kennedy D, Oei J. Infant neurodevelopment following in utero exposure to antidepressant medication. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:1054–9.

Galbally M, Lewis AJ, Buist A. Child developmental outcomes in preschool children following antidepressant exposure in pregnancy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:642–50.

Zeskind PS, Stephens LE. Maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy and newborn neurobehavior. Pediatrics. 2004;113:368–75.

Casper RC, Gilles AA, Fleisher BE, Baran J, Enns G, Lazzeroni LC. Length of prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants: effects on neonatal adaptation and psychomotor development. Psychopharmacology. 2011;217:211–9.

van der Veere CN, de Vries NKS, van Braeckel KNJA, Bos AF. Intra-uterine exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), maternal psychopathology, and neurodevelopment at age 2.5 years: results from the prospective cohort SMOK study. Early Hum Dev. 2020;147:105075.

Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Gardner HA, Theis JG, Kulin N, Koren G. Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to antidepressant drugs. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:258–62.

Nulman I, Rovet J, Stewart DE, Wolpin J, Pace-Asciak P, Shuhaiber S, Koren G. Child development following exposure to tricyclic antidepressants or fluoxetine throughout fetal life: a prospective, controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1889–95.

Nulman I, Koren G, Rovet J, Barrera M, Pulver A, Streiner D, Feldman B. Neurodevelopment of children following prenatal exposure to venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or untreated maternal depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1165–74.

Viktorin A, Uher R, Kolevzon A, Reichenberg A, Levine SZ, Sandin S. Association of antidepressant medication use during pregnancy with intellectual disability in offspring. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1031–8.

Frisell T, Öberg S, Kuja-Halkola R, Sjölander A. Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology. 2012;23(5):713–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230.

Croce RV, Horvat M, McCarthy E. Reliability and concurrent validity of the Movement Assessment Battery for Children. Percept Mot Skills. 2001;93:275–80.

Anderson PJ, Burnett A. Assessing developmental delay in early childhood: concerns with the Bayley-III scales. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017;31:371–81.

Gordon B. Test review. In: Wechsler D, editor. The Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, (WPPSI-III) , vol 19. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. Canadian Journal of School Psychology. 2004. p. 205–220.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by NA-F and AA. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by NA-F, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

The contents of this manuscript are solely the authors’ views and should not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of the Saudi Food and Drug Authority.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Fadel, N., Alrwisan, A. Antidepressant Use During Pregnancy and the Potential Risks of Motor Outcomes and Intellectual Disabilities in Offspring: A Systematic Review. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 8, 105–123 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-021-00232-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-021-00232-z