Abstract

Background

Adverse drug reactions are a recognised cause of hospital admissions. A small group of medicines carry a higher risk of adverse outcomes and are more frequently involved in hospital admissions than other medicines. These ‘high-risk medicines’ have been identified in previous research. However, it is less clear how to reduce the risks associated with these known high-risk medicines, or which high-risk medicines should be prioritised when implementing risk reduction interventions. Previous research has questioned the efficacy of pharmacist-led medication reviews in reducing hospital admissions and drug-related morbidity and mortality.

Objectives

In this study, we aimed to identify high-risk medicines through medication review to reduce iatrogenic disease; to determine a short list of high-risk medicines to target in medication reviews to achieve the greatest impact on reducing iatrogenic disease and patient harm; and to determine whether pharmacist-conducted medication reviews of high-risk medicines are safe and effective.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was undertaken in 16 general practices in one Scottish health board. All patients prescribed a high-risk medicine were identified and received a medication review from a pharmacist (3643 patients from a total population of 38,399). The pharmacist decided whether it was appropriate to continue the high-risk medicine, or if the medicine should be stopped or amended. The pharmacist made recommendations to the patient’s general practitioner (GP) for medicines to be stopped or amended, which the GP could choose to accept or not. Patient outcomes for all of the pharmacist’s recommendations were identified 1 year later to determine the effectiveness of the recommendations.

Results

High-risk medicines were prescribed to 3643 patients from a total population of 38,399 patients. The pharmacist made 440 recommendations for GPs to stop or amend high-risk medicines. GPs accepted 214 recommendations and rejected 226, giving an acceptance rate of 49 %. The 440 recommendations were then followed up 1 year later. The risk of having an adverse outcome was significantly reduced when the pharmacist’s recommendation to stop or amend a high-risk medicine was followed compared with rejecting the pharmacist’s recommendation and continuing the high-risk medicine unchanged (p < 0.001). A total of 22 adverse outcomes occurred when the pharmacist’s advice was rejected. Of these, 21 would have been prevented if the pharmacist’s recommendation had been followed and three resulted in hospital admission.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that medication reviews for high-risk medicines are safe and effective, with results achieved within 1 year of the initial review. It identified six high-risk medicines that could form the basis of targeted medication reviews in order to reduce iatrogenic disease. It also demonstrated that pharmacists are safe and effective at delivering medication reviews.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Targeted medication reviews of six key high-risk medicines can reduce iatrogenic disease in as little as 1 year. |

Pharmacists can deliver medication reviews safely and effectively. |

1 Introduction

Around 5 % of all hospital admissions are caused by adverse drug reactions, with a higher rate of up to 17 % in frail populations [1–4].

This is important in the context of polypharmacy. It is widely recognised that medication is the most common form of medical intervention: 80 % of people aged over 75 years take a prescription medicine [5]. Furthermore, there is an increasing burden of people with multiple co-morbidities. Current disease management guidelines focus on treating each disease in isolation, which results in significant levels of polypharmacy, and such guidelines do not take into account the holistic management of a patient [6]. Since work began on this study, a national polypharmacy guideline was published in Scotland to try to tackle inappropriate polypharmacy [7].

A small group of medicines is frequently implicated in hospital admissions, termed in this study as ‘high-risk medicines’. Medicines can have a higher risk of an adverse event because of three types of risk factor: the effect of the medicine itself, the result of combining two or more medicines, or patient-specific risk factors. Such high-risk medicines have been described by previous research [8] and a recent systematic literature review listed 46 tools to identify high-risk medicines and inappropriate prescribing [9]. In this study, the high-risk medicines were defined by the National Health Service (NHS) Highland Polypharmacy Guideline [10], which was a precursor to the Scottish Polypharmacy Guidance [7].

Therefore, this study was not about identifying the high-risk medicines that can cause adverse events. Instead, we hypothesised that by identifying all patients being prescribed known high-risk medicines and taking actions to minimise risk, the rate of iatrogenic disease associated with these medicines could be reduced.

The aim of our study was to identify a short list of high-risk medicines for which there is the greatest benefit to patients of targeted medication review. This short list could be used as a component of regular medication reviews in primary care by either pharmacists or GPs, with the aim of reducing iatrogenic disease and patient harm.

The value of medication review, including using a pharmacist to provide reviews, has been previously described [11, 12]. However, two large systematic reviews of 38 [13] and 32 [14] trials have found there is, at best, only weak evidence that pharmacist-led medication reviews are effective in reducing hospital admissions or drug-related morbidity and mortality. One of these reviews [13] calls for more trials of primary care-based pharmacist-led interventions to decide whether or not this intervention is effective.

We believe our study is the first to take a systematic approach to identify all patients in a defined geographical area who take a high-risk medicine, take appropriate action and then follow up 1 year later.

2 Method

2.1 Setting

NHS Highland is the largest geographical health board in the United Kingdom, covering approximately 32,500 km2 (12,500 miles2) and representing 41 % of the land mass of Scotland. The population, however, is only around 320,000 (6 % of the Scottish population). This research was conducted within the North area of NHS Highland; all 17 primary care medical practices were invited to participate.

2.2 Study Design

The study was a prospective cohort study.

2.3 High-Risk Medicines

High-risk medicines and high-risk medicine combinations were identified from the NHS Highland Polypharmacy Guidance [10] and developed with reference to additional information on anticholinergic drugs [15] and the STOPP/START tool (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions/Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment) [16]. The medicines and medicine combinations searched for in the study are listed in Table 1.

2.4 Patient Identification

All patients prescribed one or more of the high-risk medicines on a repeat prescription were identified via a search of the practices’ computerised prescribing system. There were no exclusions.

2.5 Medicines Review

The medicines review protocol was developed by an expert team of two primary care pharmacists, two hospital pharmacists and a consultant physician specialising in care of the elderly. The reviews were undertaken at the medical practices by a senior clinical pharmacist between June 2012 and February 2013. The review process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

All patients for whom a recommendation to alter a prescription was made were followed up 12 months later. This involved review of the medical notes by a team of primary care clinical pharmacists using a standard pharmaceutical resource [17] to describe and categorise the outcomes as one of the following:

-

Medicine stopped: no adverse consequences; adverse consequence; original medicine restarted; or alternative medicine started.

-

Medicine amended: no adverse consequences; adverse consequence; original medicine restarted; or alternative medicine started.

For all patients where the GP continued the medicine unchanged despite the pharmacist recommendation, the medical notes were reviewed to determine any untoward medicine-related effects including adverse drug reactions, hospital admissions or other medicine-related morbidity. Preventability of these effects was determined by reference to standard reference sources by two independent pharmacists [17]. These were categorised as one of the following:

-

Medicine continued: no adverse consequences; adverse consequences; or later actions taken.

2.6 Data Analysis

Data were recorded in a spreadsheet designed for the project by a team of primary care clinical pharmacists. Data were then analysed by the two authors working independently from each other and were cross-checked before recording the final outcomes.

A statistical analysis was undertaken using Fisher’s exact test to assess whether following the pharmacist’s recommendations altered the risk of having an adverse outcome related to a high-risk medicine. Fisher’s exact test was calculated using a 2 × 2 contingency table using GraphPad software [18]. Potential confounding factors in the decision to accept or reject the pharmacist’s recommendations were not controlled for.

2.7 Governance

This study was deemed service evaluation and hence was exempt from NHS ethical and research and development reviews.

3 Results

Sixteen of the seventeen primary care medical practices agreed to take part, with the one remaining practice expressing interest but was unable to participate due to a shortage of physician resources. The demographics of the 16 practices are provided in Table 2. The overall trend is of an older population (22 % aged over 65 years) living either in very remote small towns or very remote and rural small settlements.

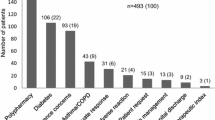

Of the combined practice populations of 38,399 patients, 9.5 % (3643) were prescribed one or more high-risk medicines. For the majority of these patients (87.4 %, 3184), the pharmacist deemed the medicine and monitoring to be appropriate, and that the benefits of continuing treatment outweighed the risks.

Recommendations to amend the prescription or deprescribe a high-risk medicine were made 459 times. Some of these recommendations involved one patient who took more than one high-risk medicine, therefore the evaluation is of 459 recommendations rather than 459 patients (21 patients had two recommendations, seven patients had three recommendations, the remainder had one recommendation). Of the 459 recommendations, 19 were for patients who were lost to follow up. Therefore, the final number of recommendations included in the study was 440. Of these 440 recommendations, 413 (94 %) were for patients aged over 60 years.

Of the 440 recommendations made, GPs accepted 214 recommendations and rejected 226, giving an average acceptance rate of 49 % (range 20–80 %, see Table 3). If the three GP practices with low acceptance rates are excluded, the acceptance rate is 61 %. Reasons for rejecting recommendations were varied: in some cases it was due to patient-specific clinical factors such as a patient’s reluctance to withdraw a hypnotic or patient willingness to accept the risks associated with a particular medicine combination. A pattern of lower acceptance rate (seen at three GP practices) may have been due to a lack of GP engagement with the study.

The 440 recommendations were then followed up 1 year later. No patients were lost to follow up. The results are summarised in Table 4. A detailed breakdown of the 440 recommendations is shown in Table 5.

In 22 (10 %) of the 226 rejected recommendations, an adverse event occurred. The 22 events are shown in Table 6. All but one of the events was the specific event that the pharmacist’s recommendation related to. Three events resulted in hospital admission and 19 resulted in an additional GP consultation.

In the group in which the pharmacist’s recommendation was rejected and the original medicine was continued, later action was taken by the GP in 24 % of cases. In 95 % of these cases, the action was the same as had been recommended by the pharmacist and was taken to reduce the risk of an adverse event. The most frequent actions were to stop a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or hypnotic, to reduce the dose of a hypnotic and to change to a safer NSAID.

In the group in which the pharmacist’s recommendation was accepted and the original medicine was stopped or amended, the original medicine had to be re-started in 16 % of cases. These medicines are listed in Table 7. The reason for medicines being re-started was identified from patients’ medical records: a reason was stated in 30 out of 35 cases. For all 30, the original medicine was re-started at the patient’s request due to a loss of symptomatic control without the medicine. Of these, 29 % were NSAIDs for pain; 29 % were hypnotics for insomnia and 23 % were tricyclic antidepressants frequently used in low doses at night only for anxiety/insomnia/pain symptoms. In no case was the need to re-start a medicine due to an adverse event. Although a loss of symptom control can be unpleasant or inconvenient for a patient, it is not considered to be an adverse event of equivalent importance to those listed in Table 6.

A statistical analysis was undertaken using Fisher’s exact test. Patients who were re-started on their original medicine were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the following data was entered in Fisher’s exact test: 179 accepted recommendations with no adverse outcomes; 226 rejected recommendations with 22 adverse outcomes. This study found that the risk of having an adverse outcome was significantly reduced when the pharmacist’s recommendation to stop or amend a high-risk medicine was followed compared with continuing a high-risk medicine unchanged (p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify the high-risk medicines for which a targeted medication review is most beneficial. Six high-risk medicine groups were identified, and therefore we recommend that regular review of these six groups would reduce patient harm. The six medicine groups are listed in Table 8; we have included a suggested action, although such actions are at the discretion of the prescriber because individual patient factors should also be considered.

This study also set out to determine if targeted medication reviews can be safely undertaken by a pharmacist. We have demonstrated that targeted medication reviews of high-risk medicines conducted by a pharmacist are both safe and effective. When the pharmacist’s recommendations were accepted, no adverse events were observed. In contrast, when the pharmacist’s recommendations were rejected, 22 preventable adverse events including three hospital admissions occurred. It is also likely that the pharmacist’s recommendations triggered later actions by GPs: in the group in which the pharmacist’s recommendation was initially rejected, the GP implemented the action at a later date in around 20 % of cases.

These findings support previous research which has described the value of pharmacist-conducted medication review [11, 12]. It also adds to the evidence base of primary care-based pharmacist-led medication reviews in reducing hospital admissions and drug-related morbidity, something called for by a previous systematic review [13].

Delivering high-quality pharmaceutical care is central to pharmacy strategy in Scotland [19]. It is hoped that as pharmaceutical care services develop, pharmacists in all settings will consider targeting medication reviews to the high-risk medicine groups identified in this study. However, such medication reviews need not be restricted to one profession. Medication review is a core component of the Quality and Outcomes Framework within the general medical services contract [20], so GPs may find it useful to target the high-risk medicine groups identified in this study.

Informal feedback from GPs during the study revealed that historically not all GPs in the practices included in the study took a holistic view to medication review. One GP commented: “I didn’t really see the value of this project until a triple whammy combination was pointed out to me. I realised I had never looked at the persons’ medicines holistically before so hadn’t considered the risk she was at”. Therefore, this study has already helped to inform better medication review among participating GP practices.

A weakness of our study is that outcomes were only reviewed after 1 year: it is unlikely that all outcomes would be observed within 1 year, and therefore a longer follow-up period would be useful. Therefore, we plan to carry out further research on the 440 recommendations in our cohort after 5 years.

A further weakness of our study was that we did not control for potential confounding factors in our statistical analysis. Our study was a prospective study which took a real-life approach. There were many potential confounding factors in the decision to accept or reject the pharmacist’s recommendations. The biggest confounder was the variability between GPs at the 16 practices in their clinical judgement on deciding whether or not to accept the pharmacist’s recommendation (see Table 3). Some GPs were less engaged in the study than others, perhaps due to time pressures or willingness to accept advice from a pharmacist. Controlling for this confounder was not possible without limiting the study to one GP practice, which would have resulted in the population size being too small. Further confounders include the patient being in an unstable condition (e.g. due to co-morbidity or life circumstances) so it being an inappropriate time to implement a change to medicines, GP knowledge of a patient’s past acceptance of medicine changes, and GP knowledge of a patient’s ability to cope with a change to medicines. Within our real-life study population, it was impossible to identify all the potential confounders. Therefore, we decided not to control for confounders. A future area for research would be to design a revised version of this study that did control for these confounders.

We do not believe there was any bias in the pharmacist’s reviews and recommendations. Each recommendation stated the evidence base upon which it was made, therefore reducing the risk of bias.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrated that medication reviews for high-risk medicines are safe and effective, and that pharmacists are effective at delivering medication reviews. It identified six high-risk medicines that could form the basis of targeted medication reviews in order to reduce iatrogenic disease.

References

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;289:1107.

Grant A, Guthrie B, Dreischulte T. Developing a complex intervention to improve prescribing safety in primary care: mixed methods feasibility and optimisation pilot study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004153.

Zhang M, Holman CDJ, Price SD, et al. Comorbidity and repeat admission to hospital for adverse drug reactions in older adults: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:a2752.

The Scottish Government and the British Medical Association. Quality and Outcomes Framework: guidance for NHS boards and GP practices, 2014/15. Edinburgh; 2014.

Dumbreck S, Flynn A, Nairn M, et al. Drug-disease and drug-drug interactions: systematic examination of recommendations in 12 UK national clinical guidelines. BMJ. 2015;350:h949.

Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates. NHS Scotland Polypharmacy Guidance. Edinburgh; October 2012.

Guthrie B, McCowan C, Simpson CR, et al. High risk prescribing in primary care patients particularly vulnerable to adverse drug events: cross sectional population database analysis in Scottish general practice. BMJ. 2011;342:3514.

Kaufmann C, Tremp R, Hersberger K, et al. Inappropriate prescribing: a systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 70(1).

NHS Highland. Polypharmacy: guidance for prescribing in frail adults. Version 3. Inverness; November 2011.

Zermansky A, Petty D, Raynor D. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ. 2001;323:1340.

Avery A, Rodgers S, Cantrall A, et al. A pharmacist-led information technology intervention for medication errors (PINCER): a multicentre, cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:1310.

Royal S, Smeaton L, Avery A, et al. Interventions in primary care to reduce medication related adverse events and hospital admissions: systematic review and meta-analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:23.

Holland R, Desborough J, Goodyer L, et al. Does pharmacist-led medication review help to reduce hospital admissions and deaths in older people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharm. 2008;65:303.

University of East Anglia. Drugs on the anticholinergic burden scale. Available at: http://www.uea.ac.uk/mac/comm/media/press/2011/June/Anticholinergics+study+drug+list. Accessed 5 Mar 2013.

Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, et al. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions) and START (Screening Tool to Alert Doctors to Right Treatment): consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;46:72.

BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. British National Formulary. Volumes 63–67. London, March 2012–2014.

GraphPad Software Inc. QuickCalcs, Fisher’s exact test 2 × 2 contingency table. Available at: http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/contingency1/. Accessed 27 Oct 2014.

The Scottish Government. Prescription for Excellence: a vision and action plan for the right pharmaceutical care through integrated partnerships and innovation. Edinburgh; September 2013.

The Scottish Government and BMA. Scottish Quality and Outcomes Framework 2013/14. Guidance for NHS boards and GP practices. Edinburgh; May 2013.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to the following: GPs and practice staff at all practices in North Highland; Tracy Beauchamp, Pharmacy Data Support Officer, NHS Highland—data entry; Lucy Dixon, Primary Care Clinical Pharmacist, North Highland, NHS Highland—data collection; Martin Wilson, Consultant Physician, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness—review of medication review tool; Martin Henderson, Head Pharmacist, Caithness General Hospital, Wick—review of medication review tool; Fiona Watson, Clinical Pharmacist, Caithness General Hospital, Wick—review of medication review tool; Derek Stewart, Professor of Pharmacy Practice, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen—advice on drafting paper; All patients who participated in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the NHS Highland Change Fund which enables local service developments to be piloted and evaluated.

Conflict of interest

Clare Morrison and Yvonne MacRae are employees of NHS Highland. Neither author has any other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

This study was a local service evaluation so was exempt from ethics approval.

Appendix 1: High-risk medicines pharmacist reporting tool

Appendix 1: High-risk medicines pharmacist reporting tool

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Morrison, C., MacRae, Y. Promoting Safer Use of High-Risk Pharmacotherapy: Impact of Pharmacist-Led Targeted Medication Reviews. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 2, 261–271 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-015-0031-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-015-0031-8