Abstract

The Italian guaranteed minimum income programme is the topic of a heated debate scarcely supported by empirical evidence. We investigate the effects of the programme on the number of days worked by different types of vulnerable jobseekers who receive the related income transfer in 2019 and are subject to activation attempts by employment services. We use data from Tuscany, in many ways a typical Italian region. To draw causal claims, we adopt a difference-in-differences approach with multiple time periods and staggered treatment adoptions. Our findings suggest that the programme has very limited heterogeneous effects among different types of users but also that, all in all, it is rather employment-neutral, in the sense that it neither creates significant disincentives to work nor succeeds in creating sufficient employment opportunities to solve the problem of job insecurity. An anti-poverty strategy that does not feed further welfare dependency would require a qualitative leap forward in activation efforts by employment services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2023, a new Italian government, considering the RDC an instrument that disincentivises labour supply, decided to cancel the measure and replace it with two new policies. The first measure, called “Assegno di inclusione”, is a sort of GMI that is no longer intended for all poor people but only for those living in households where there are members who could not work, i.e. minors, elderly or disabled people. The second measure, called “Supporto per la formazione e il lavoro”, can only be applied for once, is not renewable, and is only intended for people who can work but are in poverty.

In Germany and the UK the policy more similar to RDC is a non-contributory unemployment benefit (respectively Arbeitlosengeld II and Jobseeker’s Allowance).

Generous income support is one of the pillars behind the so called flexicurity model, together with flexible labour markets and adequate active labour market policies. Indeed, a generous income support could increase the quality of job matches and, consequently, wages.

We do not take into account possible lock-in effects for recipients attending training courses because, as we will be explained in Sect. 3, this labour market policy involves a negligible number of them.

In France, the Revenu Minimum d’Insertion (RMI) was introduced in 1989. From the very beginning the eventual labour disincentive effect was under question. In 1997, in order to incentivise labour participation, the government introduced a deduction of labour income from the means-test used for RMI that was extended for the new measure that replaced it in 2001, the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA).

In Spain, a national minimum income scheme, the Ingreso Mínimo Vital has been introduced only in 2020, but the country has a long experience of regional measures. The first region that introduced a GMI was País Vasco in 1989, followed by the other regions over the 1990s.

They consider income support and Job Seekers Allowance and Unemployment Benefit for unemployed jobseekers.

A family is eligible for RDC if it has a disposable income lower than 6000 euro (multiplied by an equivalence scale and increased to 9360 euro if it lives in rented accommodation), an ISEE (Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator) not exceeding 9360 euro, real estate assets (dwelling house excluded) not exceeding 30,000 euro and movable assets lower than 6000 euro (increased based on the family size, the presence of children or disabilities). The poverty line is implicitly determined by multiplying the threshold of 6,000 for the equivalence scale, equal to 1 for single families and increased by 0.4 for each additional family member and by 0.2 for each additional family member under 18 of age, until a maximum of 2.1 or 2.2 in the presence of disabilities). Eligibility criteria and rules for determining the magnitude of the economic benefit have been criticised and proposals have been made for readjustment (Saraceno et al. 2021).

As for the incidence of undeclared work in Italy, according to recent estimates by ISTAT it is about 13% on average, with peaks in Southern regions. In Tuscany, the region referred to in this study, it is about 11% (e.g. Reyneri 2020).

Family caregivers of children under 3 years or of severely disabled members may be exempted from the registration.

The law views, as closer to the labour market, recipients not-employed from less than two years, who benefited of contributory unemployment benefits for no more than two years, already involved in labour activation measures according to their unemployment status (see Legislative Decree 150/2015), not involved in social activation measures (see Legislative Decree 147/2017).

The adequacy of a job offer is determined by PES on the basis of the distance from the workplace to the recipient’s residence, taking into account the consistency with previous professional experiences and the adequacy of remuneration.

As described in Maitino et al. (2021), PES workers apply the normative on sanctions only for recipients who do not show at the first interview, after much prodding, and not for the cases of those who do not accept suitable job offers or do not participate in suggested training courses or selection tests. Unfortunately, the number of sanctions that have been imposed is not known.

The causal effects presented concern regular work. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that the RDC also causes changes in undeclared work, but undeclared work is not observable in the data.

As described in Sect. 3, eligibility for the benefit is a function of household-level variables, some of which have to be below predefined thresholds. These variables are unfortunately not available. If they were, an alternative identification and estimation approach could have been based on a regression discontinuity approach with multiple assignment variables. Such already very complex approach should have been extended to a setting with multiple entry and outcome timings.

Since activation efforts have intensified over time with the introduction of navigators, it would not make much sense to focus – as is done in the event study perspective – on the effects at some elapsed time after entry. In fact, early entrants awaited navigators for a few months, while later entrants immediately saw navigators spring into action.

The share of missing educational degrees is 31% for treated units (and 28% of never-treated controls). Missingness is not equally likely across all types of users and across all entry groups. For instance, it is much more likely for foreigners than for Italians. The only way to use this variable would be to create an additional level of educational attainment labelled "missing." An analysis conducted even with the educational attainment so defined leads to results very similar to those obtainable without the educational attainment. This is not surprising because the high proportion of missing values makes the covariate rather uninformative. Alternatively, one could reduce the sample to only those cases where the covariate is not missing. Since missingness occurs mainly for certain user profiles, e.g., foreigners, this would be tantamount to redefining the target population of the estimates, which is undesirable.

References

Abadie A (2005) Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. Rev Econ Stud 72(1):1–19

Abbring JH, Van den Berg GJ (2003) The nonparametric identification of treatment effects in duration models. Econometrica 71(5):1491–1517

Athey S, Imbens GW (2022) Design-based analysis in difference-in-differences settings with staggered adoption. J Econom 226(1):62–79

Ayala L, Rodríguez M (2010) Explaining welfare recidivism: what role do unemployment and initial spells have? J Popul Econ 23(1):373–392

Baldini M, Gallo G, Lusignoli L, Toso S (2019) Le politiche per l’assistenza: il Reddito di cittadinanza

Bargain O, Doorley K (2011) Caught in the trap? The disincentive effect of social assistance. J Public Econ 95(9–10):1096–1110

Bargain O, Vicard A (2014) Le RMI et son successeur le RSA découragent-ils certains jeunes de travailler? Une analyse sur les jeunes autour de 25 ans. Economie Et Statistique 467(1):61–89

Bergmark Å, Bäckman O (2004) Stuck with welfare? Long-term social assistance recipiency in Sweden. Eur Sociol Rev 20(5):425–443

Bernhard S, Kruppe T (2012) Effectiveness of further vocational training in Germany—empirical findings for persons receiving means-tested. IAB-Discussion Paper, 10

Bodory H, Huber M, Lafférs L (2022) Evaluating (weighted) dynamic treatment effects by double machine learning. Economet J 25(3):628–648

Callaway B, Sant’Anna PH (2021) Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J Econom 225(2):200–230

Cappellari L, Jenkins SP (2014) The dynamics of social assistance benefit receipt in Britain. Saf Nets Benefit Depend Res Labor Econ 39:41–79

Card D, Chetty R, Weber A (2007) The spike at benefit exhaustion: Leaving the unemployment system or starting a new job? Am Econ Rev 97(2):113–118

Card D, Kluve J, Weber A (2018) What works? A meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. J Eur Econ Assoc 16(3):894–931

Council of the European Communities (1992) Council Recommendation of 24 June 1991 on common criteria concerning sufficient resources and social assistance in the social protection systems. Brussels 50:46–48

Crepaldi C, da Roit B, Castegnaro, C., and Pasquinelli, S. (2017). Minimum income policies in EU member states. EPRS: European Parliamentary Research Service. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/1338022/minimum-income-policies-in-eu-member-states/1946206/

Danzin E, Simonnet V (2014) L’effet du RSA sur le taux de retour à l’emploi des allocataires. Une analyse en double différence selon le nombre et l’âge des enfants. Economie Et Statistique 467(1):91–116

De Angelis M, Van Wolleghem PG (2022) Do the most vulnerable know about income support policies? The case of the Italian Reddito d’Inclusione (ReI). Ital Econ J 9:1–20

De Angelis M, Pagliarella MC, Rosano A, Van Wolleghem PG, Gallo G, Scicchitano S, Vittori C, Ricci A, Cirillo V, Raitano M, Ferri V (2019) Un anno di Reddito di inclusione. Target, Beneficiari e Distribuzione Delle Risorse, Sinappsi, IX 1–2:2–21

De Chaisemartin C, D’Haultfœuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am Econ Rev 110(9):2964–2996

De La Rica S, Gorjón L (2019) Assessing the impact of a minimum income scheme: the Basque Country case. J Spanish Econ Assoc 10:251–280

De Paz-Báñez MA, Asensio-Coto MJ, Sánchez-López C, Aceytuno M-T (2020) Is There empirical evidence on how the implementation of a universal basic income (UBI) affects labour supply? A systematic review. Sustainability 12(22):9459

Filges T, Geerdsen LP, Due Knudsen A-S, Klint Jørgensen A-M, Kowalski K (2013) Unemployment benefit exhaustion: incentive effects on job finding rates: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev 9(1):1–104

Filges T, Smedslund G, Due Knudsen A-S, Klint Jørgensen A-M (2015) Active labour market programme participation for unemployment insurance recipients: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev 11(1):1–342

Fitzenberger B, Völter R (2007) Long-run effects of training programs for the unemployed in East Germany. Labour Econ 14(4):730–755

Gallo G (2021) Regional support for the national government: Joint effects of minimum income schemes in Italy. Ital Econ J 7(1):149–185

Goodman-Bacon A (2021) Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. J Econom 225(2):254–277

Hansen H-T (2009) The dynamics of social assistance recipiency: empirical evidence from Norway. Eur Sociol Rev 25(2):215–231

Heckman JJ, Ichimura H, Todd PE (1997) Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: evidence from evaluating a job training programme. Rev Econ Stud 64(4):605–654

Heinesen E, Husted L, Rosholm M (2013) The effects of active labour market policies for immigrants receiving social assistance in Denmark. IZA J Migr 2(1):1–22

Hohmeyer K, Lietzmann T (2020) Persistence of welfare receipt and unemployment in Germany: determinants and duration dependence. J Soc Policy 49(2):299–322

Hohmeyer K, Wolff J (2007) A fistful of euros: does one-Euro-job participation lead meanstested benefit recipients into regular jobs and out of unemployment benefit II receipt? IAB-Discussion Paper, 32

Huber M, Lechner M, Wunsch C, Walter T (2011) Do German welfare-to-work programmes reduce welfare dependency and increase employment? German Econ Rev 12(2):182–204

Imai K, Kim IS (2021) On the use of two-way fixed effects regression models for causal inference with panel data. Polit Anal 29(3):405–415

Imai K, Kim IS, Wang EH (2021) Matching methods for causal inference with time-series cross-sectional data. Am J Polit Sci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12685

Imbens GW, Rubin DB (2015) Causal inference in Statistics, Social, and Biomedical Sciences. Cambridge University Press

ISTAT (2020) Dati statistici per il territorio—Regione Toscana, ISTAT, Ufficio territoriale per l’Emilia Romagna, la Toscana e l’Umbria

ISTAT (2022) Noi Italia 2022, Istituto Centrale di Statistica

INAPP (2022) Reddito di cittadinanza: evidenze dall’indagine Inapp-Plus

INPS (2021) Reddito/Pensione di Cittadinanza Reddito di emergenza, Report ottobre 2021

Kluve J (2010) The effectiveness of European active labor market programs. Labour Econ 17(6):904–918

Königs S (2018) Micro-level dynamics of social assistance receipt: evidence from four European countries. Int J Soc Welf 27(2):146–156

McCall B (1996) Unemployment insurance rules, joblessness and part-time. Econometrica 64(3):647–682

Maitino ML, Ravagli L, Sciclone N (2021) I percorsi d’inclusione lavorativa in Caritas (2021), Un monitoraggio plurale del Reddito di cittadinanza, Teramo

Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali (2022) Progetto di ricerca per la valutazione contro fattuale dei percorsi di inclusione per i beneficiari del Reddito di Cittadinanza, Rome

Monti P, Pellizzari M (2010) Implementing a guaranteed minimum income in Italy: an empirical analysis of costs and political feasibility. Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia, 67–99.

Mortensen D (1970) Job search, the duration of unemployment and the Philips curve. Am Econ Rev 60(5):847–862

Nifo A, Vecchione G (2014) Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The case of Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1628–1649

Pedrana M (2012) Le dimensioni del capitale sociale Un’analisi a livello regionale. G Giappichelli Editore, Torino

Piketty T (1998) L’impact des incitations financières au travail sur les comportements individuels: une estimation pour le cas français. Économie and Prévision 132–133:1–35

Ravagli L (2015) A minimum income in Italy (No. EM16/15). EUROMOD Working Paper

Reyneri E (2020) Lavoro nero, non solo una questione meridionale. lavoce.info, 7 July 2020, https://lavoce.info/archives/68317/lavoro-nero-non-solo-una-questione-meridionale/

Rønsen M, Torbjørn S (2009) Do welfare-to-work initiatives work? Evidence from an activation programme targeted at social assistance recipients in Norway. J Eur Soc Policy 19(1):61–77

Saraceno C, Marano A, Berliri C, Giorio AC, Centra M, Checchi D, Bozzao P, Ciarini A, De Capite N, Franzini M, Gori C (2021) Relazione del Comitato Scientifico per la Valutazione del Reddito di Cittadinanza. Roma, Ministero del Lavoro e delle Politiche Sociali. https://www.lavoro.gov.it/priorita/Documents/Relazione-valutazione-RDC-final.pdf

Sianesi B (2004) An evaluation of the Swedish system of active labor market programs in the 1990s. Rev Econ Stat 86(1):133–155

Sianesi B (2008) Differential effects of active labour market programs for the unemployed. Labour Econ 15(3):370–399

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J Econom 225(2):175–199

Terracol A (2009) Guaranteed minimum income and unemployment duration in France. Labour Econ 16(2):171–182

Van den Berg GJ, Vikström J (2022) Long-run effects of dynamically assigned treatments: a new methodology and an evaluation of training effects on earnings. Econometrica 90(3):1337–1354

Vooren M, Haelermans C, Groot W, Maassen van den Brink H (2019) The effectiveness of active labor market policies: a meta-analysis. J Econ Surv 33(1):125–149

Wolff J, Jozwiak E (2007). Does short-term training activate means-tested. IAB-Discussion Paper, 29

Wolff J, Nivorozhkin A (2012) Start me up: The effectiveness of a self-employment programme for needy unemployed people in Germany. J Small Bus Entrep 25(4):499–518

Wunsch C (2016) How to minimize lock-in effects of programs for unemployed workers. IZA World of Labor

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

This appendix is devoted to presenting the main results of the paper relying on the identifying assumption of conditional parallel trends based on a not-yet-treated group.

There are \(i=1,\dots ,N\) units, \(t=1,\dots ,\tau\) time periods, and \(g=1,\dots ,G\) entry timings into treatment, defining entry cohorts/groups. By assumption, once a unit becomes treated, that unit will remain treated in the following periods (irreversibility of treatment). Note that g is also a time counter, and that, for each entry cohort, the \(\tau\) available time periods can be partitioned into two temporal phases: every \(t<g\) is before entry; every \({\text{t}}\ge g\) is after entry.

Let \({G}_{g}\) be a binary variable equal to 1 if a unit is first treated in time period g and \({D}_{it}\) be an indicator variable for whether unit i has been treated by time t (= 1) or will receive treatment in the future (= 0).

Under the assumption that there is no interference between units (Stable-Unit Treatment Value Assumption), \({Y}_{it}\left(g\right)\) is unit i’s observed potential outcome at time t, \(t\ge g\), if the unit first becomes treated in time period g, while \({Y}_{it}\left(0\right)\) is unit i’s unobserved potential outcome at time t, \(t\ge g\), had that unit remained untreated. Causal effects for a given entry group g are defined as the group-time average tratment effect on the treated:

To identify the \(ATT\left(g,t\right)\) we now invoke the assumption of conditional parallel trends based on a not-yet-treated group, which states that—in the absence of treatment—the post-intervention outcome variations over time of actually treated units would have been the same of that units that will take up treatment in the future and that exhibit their same observable characteristics.

For each entry group g and for each \(\left(s,t\right)\in \left\{g, \dots ,\tau \right\}\times \left\{g, \dots ,\tau \right\}\) the assumption can be written as follows:

Since potential outcomes without the treatment are observed quantities in the control group, the assumption in [A2] makes it possible to use the information from the control group to impute the missing expectation of potential outcomes.

for the treated group had it not been treated. The resulting DiD estimator is as follows:

As in the main analysis, the covariates with respect to which we will assume conditional parallel trends are: sex (female/male); citizenship (Italian/other countries); age group (up to 29 years; 30–39; 40–49; 50 years or older); the sector in which the individual predominantly gained work experience prior to the launch of the programme (agriculture, manufacturing, construction, retail/tourism, cleaners/caretakers, other services, no sector since the individual did not work); the cumulative number of days worked divided by the cumulative number of workable days and we employ the “doubly robust” estimator put forward by Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) also in this supplementary analysis based on a not-yet-treated control group.

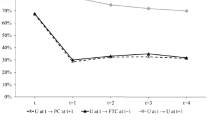

The aggregation of the \(ATT\left(g,t\right)s\) by calendar month estimated using the approach described so far is reported in Fig. 5.

Considering the different profiles of recipients as a whole, we estimate—aggregating the entire post-intervention period—a positive but very limited average effect of RDC on the treated equal to 0.69 monthly working days (95% Confidence Interval: 0.32; 1.05).

These results are more optimistic than those obtained under the never-treated approach, although the precision of these new estimates is not always excellent due to the dramatic reduction in the numerosity of the control group. However, comparability is limited since, with the not-yet-treated approach, we can only estimate effects for a maximum of 8 post-intervention time points, whereas with the never-treated approach we can estimate effects up to 22 post-intervention time points.

Appendix 2

See Table 3

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Maitino, M.L., Mariani, M., Patacchini, V. et al. The Employment Effects of the Italian Minimum Guaranteed Income Scheme Reddito di Cittadinanza. Ital Econ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00263-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00263-1