Abstract

This paper aims to investigate whether a wealth endowment, such as an inheritance or a gift, can increase the chances of getting divorced, using Dutch panel data for the period from 2002 to 2016. According to the literature, different factors may lead to the breakdown of a marriage; however, the role played by inherited wealth has never been explored so far. Starting from the idea that the receipt of an inheritance might have an impact on various aspects of an individual’s life, estimations of a Cox proportional hazard ratios model are performed and tests are carried out to establish which variables, with particular attention being given to inherited wealth, act as drivers in increasing the chances of withdrawing from a marriage. The findings suggest that when the wealth endowment has been received by the wife, this increases the chances of the couple separating. This signals that receiving an inheritance/gift changes the bargaining power between the couple: for the husband, it does not represent an incentive to divorce, while the results suggest that the wife might perceive a change in the bargaining power, increasing the likelihood of marital disruption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, one of the main issues in many countries and many economic organizations (such as the OECD) has been closing the gender gap between women and men. Gender equality concerns not only rights but also power and benefits, which include, for example, the reduction of poverty. The reduction of poverty is reflected in the economic dependence of women in households; very often, after marriage and/or giving birth to a child, a woman has to leave her job or opt for a part-time position. To put the spotlight on the Netherlands, which represents the country of my analysis, Statistics Netherlands (CBS) says that ‘only 52% of women are economically independent, and only 54% of women are convinced that it is important to be able to support themselves and their children’. Bearing this in mind, does this economic dependence represent an obstacle to withdrawing from a marriage that is no longer working out? Could ‘monetary help’ have an impact in the household, and how could this change the bargaining power between the couple? These and other similar questions represent the motivation for my analysis. What I would like to do in this study is to provide evidence of a potential increased likelihood of divorce caused by the receipt of an inheritance or a transfer. According to the literature, the motives for divorce are a consequence of different factors such as religion, family-related features, the presence of children, and so on (Amato and Afifi 2006). In addition, the probability of future divorce depends strongly on female participation in the labour market. Interruptions in participation in the labour market caused by marriage, as well as by the birth and presence of children, can have long-term effects through lower future wages associated with less labour market experience, making a woman more economically dependent on her husband (van der Klaauw 1996; Pestel 2017).

The objective of this paper is therefore to study whether receiving an inheritance or a transfer can, in some way, increase the chances of getting divorced. The contribution of my paper is twofold: first, this work represents, to the best of my knowledge, one of the first to provide evidence on the relationship between wealth endowment and divorce. Secondly, the results of my paper contribute to the literature on bargaining power in couples, since I show how a money endowment affects the decision-making process. In addition to this, what I am demonstrating is that the receipt of an inheritance within the household can lead to a break in the balance within the couple, leading potentially to a marital conflict.

My empirical methodology involves the use of the DNB Household Survey (DHS), a Dutch panel data set collected by the CentERdata that allows both the psychological and the economic aspects of financial behaviour to be studied. This panel survey was launched in 1993 and comprises information on work, pensions, housing, mortgages, income, possessions, loans, health, economic and psychological matters, and personal characteristics. For reasons of data availability and to have a representative sample of the Dutch population, I concentrate my analysis on Dutch households of couples in the years from 2002 to 2016.Footnote 1

Starting from the idea that the receipt of an inheritance could affect different aspects of an individual’s life, I perform a Cox proportional hazard ratios model to estimate the probability that a married couple divorces, and the way in which this probability varies through time, identified by the duration of the marriage. My aim is to understand the role of the receipt of an inheritance/gift, differentiating between inheritances/gifts received by the husband and those received by the wife, and the role of other covariates that might have an impact on the transition probability. The findings suggest that when the inheritance/gift is received by the husband, there is a significant negative impact on the likelihood of getting divorced, while when the inheritance/gift is received by the wife, this increases the chances that the couple will separate. One possible interpretation of these results is that the receipt of an inheritance/gift changes the bargaining power between the couple: for the husband, who is probably already in the dominant position in the household, the endowment of wealth by means of an inheritance or a gift does not represent an incentive to divorce, while the results seem to suggest that the wife might perceive a change in the bargaining power between the couple, resulting in an increase in the chances of marital disruption. This result is also confirmed when differentiating between the case in which the income of the wife belongs to the bottom quintiles of the distribution, and when her income lies in the top classes of income distribution.

Possible concerns might arise about whether any causal conclusion can be drawn from this work: the receipt of an inheritance is an endowment of wealth that is only included in my analysis (as will be explained in more detail in the description of the main variables) if it comes before divorce (the inheritance/transfer variable has been constructed as a lag variable to avoid any simultaneity between the receipt of an inheritance and divorce). Moreover, I also conduct the analysis excluding endogenous regressors (such as the variable recording the number of children in the household), and the results still hold.

The rest of the paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework. Section 3 describes the data. Section 4 provides the empirical methodology, the main findings and some robustness and heterogeneity checks. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 Literature Framework

For years, the role played by inherited wealth as a fundamental driver of matrimonial strategies has represented a very interesting topic. As pointed out by Pasteau and Zhu (2018), the importance of inherited wealth in nineteenth-century Europe was highlighted by Thomas Piketty in his work Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014). Piketty provided insights into the rigid structure of the societies of ‘patrimonial capitalism’ in France and Great Britain at that time. In his work, Piketty (2014) argued that recent decades have seen a return of the importance of inherited wealth in those two countries, together with an increase in wealth inequality, which may lead to a renewed importance of inherited wealth in mating choices.

An inheritance can be conceived as ‘unearned income’ that, according to the life-cycle model, has an impact on economic and other outcomes (Imbens et al. 2001). Brown et al. (2010) treated a receipt of inheritance as a wealth shock and found that it was associated with a significant increase in the probability of retirement, especially when the inheritance was unexpected. The role of wealth in modelling labour decisions has been broadly considered for its effects on early retirement (Krueger and Pischke 1992; Bloemen and Stancanelli 2001; Brown et al. 2010), on labour market participation (Bloemen and Stancanelli 2001), and on hours worked (Imbens et al. 2001; Henley 2004). Along these lines, inheritance might, for example, affect labour supply (Joulfaian and Wilhelm 1994); indeed, Bloemen and Stancanelli (2001) found that wealth has a significantly positive impact on reservation wages and a negative impact on employment probability (higher levels of wealth result in higher reservation wages, and higher reservation wages are associated with a lower employment probability).

Recent evidence has focused on the effect of receiving an inheritance on labour force participation (LFP) in married couples, finding that bequests might, indeed, increase the bargaining power of the recipient, affecting his/her LFP, and providing new evidence of the ability of spouses to commit to a fully efficient allocation of resources within the household (Blau and Goodstein 2016). Many aspects of wealth changes, and their impact on consumption choices, have been studied with reference to real estate wealth changes (Calcagno et al. 2009), including inheritance receipt and its impact on labour supply (Brown et al. 2010). Recent findings have extended these views and investigated the potential effects of receiving an inheritance on other personal features of individuals, such as, for example, the intention to bequeath (Stark and Nicinska 2015).

As pointed out in the Introduction, the aim of this work is to provide evidence on another, more personal, aspect of an individual’s life, that is, divorce. Exploring the vast literature, the motives for divorce are a consequence of various factors that affect the risk of divorce. Indeed, religion has a clear negative effect on the likelihood of divorce (Amato and Afifi 2006). The effect of a parental divorce can be significant and substantial; people whose parents divorced (when they were growing up) might have higher chances of divorce than other people. By contrast, having children is associated with lower odds of divorce (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2006a). Recent studies have focused on the introduction of unilateral divorce legislation (Stevenson and Wolfers 2006; Wolfers 2006); in this vein, allowing people to file a divorce unilaterally increases individual well-being (Stevenson and Wolfers 2006) and children’s well-being (Reinhold et al. 2013), and might reduce domestic violence (Pollak 2004; Brassiolo 2016).

Needless to say, features other than a wealth endowment might affect the chances of getting divorced: the motives for divorce might also rely on other, more personal, features such as, for example, patience.Footnote 2 In this regard, the literature has highlighted the important link between time preferences and marital stability; impatient individuals will seek to exit a marriage as soon as a shock occurs. An illustration of the correlation between impatience and marriage stability is found in the work of Compton (2009); the author, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) data, found that more patient individuals tended to remain in a marriage after a marital shock, while more impatient individuals tended to look for a ‘way out’. Similar results come from the conviction that marriage can be considered as the result of spouses’ willingness to invest in the long-term viability of the marriage and to accept short-term disadvantages, giving rise to a lower propensity of divorcing (Compton 2009; De Paola and Gioia 2017).

Furthermore, a woman’s labour force participation can be a cause of divorce (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2006b); indeed, marriages with a working wife run a higher risk of divorce than marriages in which the wife is unemployed (Cherlin 1979; Spitze and South 1985; South and Spitze 1986; Greenstein 1990; Tzeng and Mare 1995; Babka von Gostomski et al. 1998; South 2001; Poortman and Kalmijn 2002). Along these lines, generally, women showing characteristics appreciated and valued in the marriage market appear less likely to work outside the home (Grossbard-Shechtman and Neuman 1988). Indeed, an increase in the expected earnings of the woman actually appears to increase the probability of dissolution of the marriage and reduce the propensity to remarry (Becker et al. 1977). In studies of female labour supply, for example, there is growing awareness that both marital status and fertility decisions are strongly related to female labour supply decisions, and can no longer be considered to be exogenous from a life-cycle perspective (van der Klaauw 1996). In addition, the probability of future divorce depends strongly on female labour market participation. Interruptions in labour market participation caused by marriage, as well as the birth and presence of children, can have long-term effects through the reduction in future wages associated with less labour market experience, making the woman more economically dependent on her husband (van der Klaauw 1996; Pestel 2017).

3 Data and Institutional Framework

3.1 Institutional Framework

Before proceeding with the description of the data, it would be interesting to give a brief illustration of the divorce rules in the NetherlandsFootnote 3 and to consider some changes in divorce procedures that have occurred in the last two decades in the Netherlands.

3.1.1 Divorce in the Netherlands

As reported by the CBS, between 1 April 2001 and 1 March 2009 it was possible for married couples in the Netherlands to convert their marriage into a registered partnership; this partnership could then be annulled without the parties having to go to court. For some couples, this so-called ‘flash divorce’ (flitsscheiding) was a serious alternative to divorceFootnote 4; the increase in the number of flash divorces almost completely compensated for the decrease in the number of divorces in years prior to 2009. As shown in Fig. 1, the highest numbers of flash divorces were recorded in the years from 2003 to 2005, when around 5000 couples annually separated using this procedure. The number of flash divorces was at its lowest in 2001, when the procedure was introduced, and in 2009, when it was rescinded.

Certain arrangements must be made before a divorce, a legal separation, or the termination of a registered partnership can occur. First of all, the couple wishing to legally separate, divorce, or terminate their registered partnership have to draw up a settlementFootnote 5 in which they set out their agreement concerning (possible) children, maintenance, pensions, and other matters; they then submit a petition for divorce to the court through a lawyer. There are three ways in which married partners can separate: divorce; legal separation (the partners are still married but they do not live together); and dissolution of the marriage after legal separation.Footnote 6 After the court issues a divorce decree, the individuals must finalize the divorce by recording it in the registry of births, deaths, marriages, and registered partnerships in the municipality where they married.

One important issue to be considered when talking about divorce is the cost of divorce proceedings. The costs comprise:

-

Court fees These must be paid to file a petition for divorce;

-

Legal fees These are the costs related to the (possible) engagement of a lawyer to file the divorce petition with the court; and

-

Mediation fees The couple may also wish to engage a mediator.Footnote 7

So far, the rules related to divorce in the Netherlands seem to be the same as the rules elsewhere; however, the Netherlands has different rules from other countries concerning the financial consequences of marriage. In many countries, marriage does not affect the assets of the spouses; possessions, except for their premarital assets, gifts, and inheritances, are deemed to be mutual property from the day the couple marry. The same cannot be said for the Netherlands. Couples who do not arrange a marriage settlement are automatically married under the ‘community of property’; this means that, through marriage, all their assets, including all their premarital assets, gifts, and inheritances, become common property.Footnote 8 At this point, since this paper deals with inheritance and gifts, it is useful to mention how inheritances and transfers are taxed in the Netherlands, since inter-vivos transfers might sometimes represent close substitutes for inheritances, and may come with tax advantages.

3.1.2 Information on the Taxation of Inheritances and Gifts in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, gifts and inheritances are subject to different principles, depending on the ‘intergenerational relationship’ between the provider of the gift/inheritance and the recipient. One of the most glaring aspects that comes to mind when talking about a donation or an inheritance is related to paying taxes; however, according to the Belastingdienst, there are some exemptions, depending on the amount of the gift/inheritance and also depending on the relationship with the donor. For example, in 2016, the maximum tax-exempt amount that could be given by a parent to her son, daughter, or foster child was about 53,000 euros, once in the lifetime of the child. It is also possible to make a tax-exempt donation to a child of about 5300 euros in each year. In Appendix C, I present some examples concerning exemptions and tax rates on donations/inheritances.

3.2 Data Description and Descriptive Statistics

The empirical analysis relies on the DNB Household Survey (DHS), a Dutch panel study collected by the CentERdata, a survey agency at Tilburg University specializing in internet surveys. The panel survey was launched in 1993 and comprises information on work and pensions, accommodation and mortgages, income and health, assets and liabilities, and economic and psychological concepts. The questionnaires are sent to respondents on the internet, the respondents fill in the questionnaires on their home computers, and then the answers are sent back in the same way. This implies that the questionnaires are self-administered and that individuals can answer at the most comfortable time for them. It is important to note that the selection of panel members for the survey does not depend on internet access; indeed, households without a computer or an internet connection are provided with the necessary equipment. I focus on Dutch households of couples during the years 2002–2016.Footnote 9

When dealing with panel data, it is commonplace to fear that the members who leave the panel will systematically differ from those who remain in it and that therefore the dataset is not actually representative of the population (Winkels and Withers 2000). Hence, following Fitzgerald and Gottschalk (1998), I then tested whether the attrition in panel data was random: I therefore estimated a probit in which the dependent variable assumes the value one for households which drop out of the sample after the first wave and zero otherwise using as explanatory variables all variables that might affect the outcome variable of interest. After that, as pointed out by Outes-Leon and Dercon (2008), I examined the pseudo-R-squared from attrition probit, as it can be interpreted as the proportion of attrition that is non-random. Fortunately, the pseudo-R-squaredFootnote 10 is equal to 0.0077, a very low value that excludes that there is an attrition bias in my data.

A complete description of all the variables can be found in Table 1 in “Appendix A”. Instead, descriptive statistics are reported in Table 2 in “Appendix A”; considering that I am dealing with household couples, I differentiate between wife, husband, and household characteristics.

On average, it appears that there are wide differences in the personal incomes of spouses; indeed, the mean net annual income of wives (around €6000) is much lower than that of husbands (around €16,000). This fact is also reflected in the percentage of working wives (around 44%) being lower than the figure of around 60% for working husbands; concerning educational attainments, no great differences arise from the comparison between women and men even though, focusing on university education, it appears that the percentage of husbands with a university education is higher than the percentage of wives (around 13% versus 7%, respectively). Finally, it might be worth noting that the mean duration of marriage, the variable that represents my time period for the empirical analysis presented in next section, is around 23 years, which is quite high considering that, overall, the average age of household members ranges between 53 and 55 years old.Footnote 11

3.2.1 Main Variables of Interest

As explained so far, the aim is to study whether the receipt of a money endowment, being it an inheritance or a gift,Footnote 12 might lead to marital disruption. With this in mind, I present the time-series of the different marital statuses of the individuals in my sample.

As shown in Fig. 2, the frequency of divorce is quite low compared with the frequency of marriages. For this work, I constructed the dependent variable ‘divorce’ as a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 if the couple divorced in a certain year and the value of 0 otherwise.

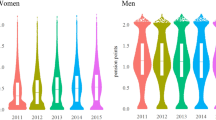

The other feature of concern related to the receipt of an inheritance/gift; in relation to this, and with the aim of avoiding cases in which the couple were divorced before the inheritance receipt, I created a lag variable for the respondents who received an inheritance. This variable takes the value 1 when the individual received an endowment in the previous year and 0 otherwise. The percentage of people who received an inheritance represented around 6–8% of my sample population. Since I was dealing with couples, I made a distinction between cases in which the inheritance/gift was received by the husband and cases in which it was received by the wife (see Fig. 3); in this way, when conducting the empirical analysis, I was able to capture any bargaining power that was present between the couple.

One possible concern could be related to the fact that the inheritance/gift, even if it was received by an individual, was perceived to have been received at the couple level, so that, although the recipient was his/her spouse, the non-recipient partner answered the question positively; however, the number of cases (around 50 couples) in which both spouses affirmed that they had received an inheritance/giftFootnote 13 was very small.

Of course, features other than a wealth endowment might affect the chances of divorce; for this reason, I control for some variables related to the household, such as the mean age in the household, the difference in age between the spouses, the educational level of the head of the household and the differential in educational attainments between the partners, the income of both partners, and whether (and how many) child(ren) were present in the household. As for the last of these variables, I report on the number of child(ren) present in the household since the number of children in the household could have a different impact on the chances of getting divorced than the mere presence of children in the household.

4 Empirical Analysis and Results

In order to better understand the link between receiving an inheritance/gift and the chances of getting divorced, and so to exploit the duration of the relationship of the spouses more successfully, I adapted a survival analysis model using the Cox proportional hazard ratios model.Footnote 14 The Cox (1972) model is expressed by the hazard function denoted by \(h\left( t \right)\); in this case, the hazard function can be interpreted as the risk of divorcing at time \(t\). Hence, it can be estimated as follows:

where \(t\) represents the survival time, \(h\left( t \right)\) is the hazard function, determined by a set of \(p\) covariates \(\left( {x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots , x_{p} } \right)\), and the coefficients \(\left( {b_{1} ,b_{2} , \ldots , b_{p} } \right)\) measure the impact. The term \(h_{0}\) is called the baseline hazard. In particular, I estimated the probability that a married couple divorced, and the way in which this probability varies through time, identified by the duration of the marriage (in years).Footnote 15 The aim is to understand the role of the receipt of an inheritance/gift, differentiated between those received by the husband and those received by the wife, and the role of other covariates that might affect the transition probability. The data were therefore treated as is generally done in survival analysis or unemployment duration models, with the time analysis being the duration of the marriage and the potential failure being identified as the end of the marriage (that is, the divorce). In this way, I was able to follow the couples until the separation occurred.Footnote 16 Thus, I estimated the hazard function \(h(t)\) that determines the probability that the couple moved from marriage to divorce at time\(t\), that is, the risk of divorcing at time\(t\), which is identified as the duration of the marriage. The set of covariates for which I controlled (presented and discussed in the previous section) were, for example, whether the recipient of the inheritance was the husband or the wife, few dummy variables for the educational level of the head of the household, and the personal net annual income of both partners (in logarithmic form). I also included the gap in the educational level between the spouses with the aim of capturing the bargaining power, if any.

4.1 Main Results

In Table 3 in “Appendix B”, main estimates are presented. It appears that, when the inheritance/gift is received by the husband, there is a negative and significant impact on the likelihood of getting divorced, while when it is received by the wife, this increases the chances that the couple will separate. This suggests that receiving an inheritance/gift changes the bargaining power between the couple: for the husband, who is probably already in the dominant position in the household, a wealth endowment does not represent an incentive to divorce, while for the wife, it appears that she might perceive a change in the bargaining positions of the couple, increasing the chances of marital disruption.

As for the control variables, it is interesting to notice that the presence of child(ren) in the household seems to deter divorce.Footnote 17 This result is in line with the literature supporting the fact that children increase marital stability, particularly when they are very young (Huber and Spitze 1980; Waite and Lillard 1991; De Graaf and Kalmijn 2006a). However, it has to be said that, contrary to what is generally thought, women often ask for divorce despite the presence of children (Brinig and Allen 2000).

At this point, an important piece of information that might be worth including is the amount of the inheritance received by the individualsFootnote 18; therefore, since the individuals were asked to report the amount of the inheritance/gift they received, I exploited this information, using, as a control, the amount of the inheritance/gift received (in logarithmic form), instead of the dummies indicating who benefited from the wealth endowment.

The results, presented in Table 4 in “Appendix B”, confirm the previous findings. It appears that also in this case the bargaining power changes after an inheritance/gift has been received. Indeed, it appears that a gender effect is present, suggesting that, when the inheritance/transfer is received by the wife, divorce is more likely to occur. This fact could be partially related to some traits that I could not observe. Kalmijn et al. (2004) argued that the validity of economic explanations of divorce (that is, the high likelihood of divorce if the woman is in paid work and has attractive labour market resources), is conditional on cultural values. Indeed, cultural hypotheses have argued that the chances of divorce increase if the woman adheres to emancipatory norms, independent of her labour market position.

Following this line, the negative and statistically significant coefficient of the difference in educational level in the household again supports the importance of the bargaining power between the couple. Indeed, as long as the difference in educational attainments increases, keeping the education of the head of household, for which I controlled, constant (meaning that the educational attainment of the wife is becoming lower), the decrease in the chances of getting divorced signals the low bargaining power of the wife.

4.2 Robustness and Heterogeneity Checks

A recurring aspect in the analyses carried out so far is linked to the presence of children in the household. As mentioned up to this point, the literature suggests that having children could be a deterrent to marriage so as to avoid, for example, problems not only for parents but also for the growth of their children. For this reason, I therefore performed a dividing analysis between those who have children living together within their household or not. Indeed, the results, reported in Table 5 in “Appendix B”, suggest that the likelihood of a marriage breakdown occurring in couples who have cohabiting children is very low. Conversely, when there are no children present in the household, the likelihood of divorce occurring when the wife has received the inheritance is positive and significant. Going back to the main findings, presented in the previous section, it appears that the bargaining power between the couple is an important aspect that deserves special attention. Along this line, I analysed whether the results change when considering the income distribution of the wife, the less ‘powerful’ figure in the couple. I longs to the bottom quintiles of the distribution, and those for which the income lies in the top classes of the wives’ income distribution. The results are reported in Table 6 in “Appendix B”; it appears that the inheritance receipt increases the chances of getting divorced when the wife’s income is low. A possible interpretation of this could lie in the fact that, potentially, women whose income is at the bottom of the income distribution represent those whose bargaining power in the marriage is non-existent or very low, so that an inheritance receipt might constitute empowerment leading towards marital disruption. On the other side, I did not observe any increase in the chances of getting divorced for the cases in which the wife belongs to the top levels of income distribution; as for the results for the previous specifications related to the inheritance receipt by the husband, for wives with high incomes, when bargaining power between the couple could potentially be almost equal, a wealth endowment, such as an inheritance or a transfer, does not represent an incentive to divorce. In addition to that, since we cannot exclude that it may be the husband that initiates divorce, the inheritance may change the value of marriage and bring about marital conflict. Indeed, the fact that lesser educated or lower-earning women are more likely to divorce than higher-educated or higher-earning women could be due to the reaction of lesser educated husbands, if there is positive assortative mating. Along this line, considering the first column of Table 6 in “Appendix B”, the negative and statistically significant coefficient of the difference in educational level in the household supports the importance of bargaining power between the couple; indeed, as long as the difference in educational attainments increases, the decrease in the chances of getting divorced signals the low bargaining power on the side of the wife. Therefore, the fact that there is a gap in education within the household can give rise to a potential marital conflict and therefore be a cause of divorce. Hence, I carried out a final and further analysis which exploits precisely the difference in level of education present within the family unit. I then performed the estimation by differentiating between the case in which the gap is positive or not: if the gap is positive, this indicates that it is the husband who has a higher level of education than the wife. In the opposite case, obviously it is the wife who has a higher level of education than her partner. Therefore, in line with expectations, it appears that when the man is less polite than his wife, then the probability that a divorce will occur is positive (results reported in Table 7 in “Appendix B”).

5 Final Remarks

It is therefore clear that the reasons that can lead to divorce are different. Certainly, among these there is the monetary component. Generally, it is often thought that it is the man who opts for the breakup of marriage. In spite of this, this work aims to demonstrate that, when the balance within the couple changes, it can be the wife herself who takes control of the situation and tries to regain her independence. Obviously, there can be several factors, that unfortunately with the data at my disposal I was not able to measure, that certainly corroborate for this situation to occur; just think, for example, of the quality of marriage which can certainly play a fundamental role (it seems reasonable to suppose that divorce is more likely to occur when the quality of the marriage is very low). Secondly, one possible concern could be that an individual who expects an inheritance could opt to separate from his/her partner in order to avoid the possibility of having to split the amount he/she will receive in the future. Aware of the fact that there may be various limitations related to the analysis carried out so far, however, this work represents, at least to the best of my knowledge, one of the first studies of the link that exists between having received a wealth endowment and divorce. The results presented in this work appear robust to different specifications; indeed, the robustness and heterogeneity checks contribute to the support of the thesis in question.

Overall, this work can represent a good starting point for future research that could analyse and expand on this relationship. All in all, I have shown, in line with what Gray (1998) found, that wives, with some proper incentives, are responsive to changes in their bargaining positions within marriage. This has valuable welfare implications for divorce law reforms and for designing social and economic policies. Along this line, as pointed out in Brinig and Allen (2000), this suggests that divorce incentives should be re-examined as the forces affecting net benefits from marriage may be quite complicated, and perhaps asymmetric between men and women. Indeed, any change in divorce law related to the financial wellbeing of divorcing women could have important consequences for the welfare of individuals in families that do not opt for dissolution.

6 Appendices

6.1 A. Appendix A: Description of Variables and Descriptive Statistics

6.2 B. Appendix B: Regression Tables

6.3 C. Appendix C

The exemptions and rates for gift and inheritance tax are corrected each year with an inflation correction. An exemption means that the recipient pays donation tax only if the value of the donation is higher than a certain amount. The following tables report the gift/inheritance exemptions.Footnote 19

In the case in which the value of the donation is less than or equal to the exemption amount then the recipient does not pay gift/inheritance tax; on the other hand, if the value of donation is higher than the exemption amount, the recipient has to pay tax on the amount that exceeds the exemption. The amount of gift/inheritance tax to be paid depends on the relationship with the donor/deceased and the value of the donation (Tables 8, 9, 10).

Notes

More details about the choice of these years are provided in the next section.

For the time being, the data at my disposal do not allow me to construct a measure for patience. However, it would definitely be useful to control for this aspect too, and this may be an area for future research.

The information provided comes from the Rijksoverheid (the Dutch government) and the Belastingdienst (the Dutch Tax and Customs Administration).

In March 2009, the government stopped allowing the flash divorce option, and the divorce procedure reverted to earlier conditions. More detailed information about flash divorces can be found in Kabatek (2019).

Settlements are usually, but not necessarily, drawn up by a lawyer; moreover, there is no obligation to draw up a settlement.

If the couple have a registered partnership, are in agreement, and do not have children, the partners can also terminate their relationship out of court.

Though not required, a mediator can help individuals make arrangements that work for both of them. In some cases, legal aid is available to cover some of the costs involved; if the couple have legal expenses insurance, the insurer may reimburse them for some or all of their costs.

However, it is important to highlight that, even if this seems the natural course of events, there is the possibility of contesting the community of property in court; it might therefore be the case that, during the divorce proceedings, the recipient of a huge wealth endowment as a gift/inheritance goes to court so that the received inheritance is treated as his/her own.

These years were chosen because in the years before 2002 this survey was the VSB-CentER savings project, and in 2002 there were some changes, both in the direction and management of the survey and in the sampling procedure, and some individuals also dropped out from the survey; with this in mind, I started the analysis from 2002 so that I was sure that I could follow the couples over time.

Results not reported but available upon request.

Even if the duration of the marriages may appear long, it is in line with the ages of the individuals making up the couples. Indeed, the couples with long marriages were the ones whose ages were higher. So as not to lose any observations, I decided to keep them in my sample, but also noted that when conducting the analysis without those observations the results hold.

The exact wording of the question asking about an inheritance receipt was “Did you receive any inheritances and/or gifts in (year)?”. The data did not allow me to distinguish whether the wealth endowment was an inheritance or a gift.

As a robustness check (results not provided in the paper but available upon request to the author), I also conducted the analysis without the cases in which both partners stated that they had received an endowment the year before, and the results hold.

I am aware that the model used is not generally a common choice. However, it is actually intended. In fact, exploiting the data available, I am able to capture and identify the divorce as if it were some kinds of marriage failure. So, I decided to opt for a duration model also to offer a new estimation model to study this phenomenon. Nevertheless, I would like to say that I also performed other methods of estimation models, such as for example OLS with fixed effects, but results (not reported but available upon request) were exactly the same.

Unfortunately, I am unable to verify whether the couple is formally married or has signed a cohabitation contract; otherwise, it would have been very interesting to perform checks in that direction too.

Those who were already divorced at the beginning of the time period in the analysis are not present in my data set.

I also conducted various analyses so to test the robustness of this result. I therefore performed the analysis without any covariates except my variables of interest, I added other covariates such as for example the region of residence, I also excluded potential endogenous regressors such as the number of children in the household. In all cases, the results still held.

Unfortunately, I do not have information about the type of inheritance/gift so I could not distinguish whether the inheritance consisted of money, land, or other assets; in addition, the data did not tell me who made the bequest or the transfer.

For convenience, I report data from the last year of the time period analysed in this work.

References

Amato PR, Afifi TD (2006) Feeling caught between parents: adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well-being. J Marriage Fam 68(1):222–235

Babka von Gostomski C, Hartmann J, Kopp J (1998) Soziostrukturelle bestimmungsgründe der ehescheidung. Eine empirische Überprufung einiger hypothesen der familienforschung [Social-structural antecedents of divorce]. Zeitschr Soziol Erziehung Sozial 18(2):117–133

Becker GS, Landes EM, Michael RT (1977) An economic analysis of marital instability. J Polit Econ 85(6):1141–1187

Blau DM, Goodstein RM (2016) Commitment in the household: evidence from the effect of inheritances on the labor supply of older married couples. Labour Econ 42:123–137

Bloemen HG, Stancanelli EG (2001) Individual wealth, reservation wages, and transitions into employment. J Law Econ 19(2):400–439

Brassiolo P (2016) Domestic violence and divorce law: when divorce threats become credible. J Law Econ 34(2):443–477

Brinig MF, Allen DW (2000) ‘These boots are made for walking’: why most divorce filers are women. Am Law Econ Rev 2(1):126–169

Brown JR, Coile CC, Weisbenner SJ (2010) The effect of inheritance receipt on retirement. Rev Econ Stat 92(2):425–434

Calcagno R, Fornero E, Rossi M (2009) The effect of house prices on household consumption in Italy. J Real Estate Financ Econ 39(3):284–300

Cherlin A (1979) Work life and marital dissolution. In: Levinger G, Moles OC (eds) Divorce and separation: context, causes and consequences. Basic Books, New York, pp 151–166

Compton J (2009) Why do smokers divorce? Time preference and marital stability. In: WP: Department of Economics, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B (methodol) 34(2):187–202

De Graaf PM, Kalmijn M (2006a) Change and stability in the social determinants of divorce: a comparison of marriage cohorts in the Netherlands. Eur Sociol Rev 22(5):561–572

De Graaf PM, Kalmijn M (2006b) Divorce motives in a period of rising divorce: evidence from a Dutch life-history survey. J Fam Issues 27(4):483–505

De Paola M, Gioia F (2017) Does patience matter in marriage stability? Some evidence from Italy. Rev Econ Household 15(2):549–577

Fitzgerald J, Gottschalk MR (1998) An analysis of sample attrition in panel data. J Hum Resour 33(2):251–299

Gray JS (1998) Divorce-law changes, household bargaining, and married women’s labor supply. Am Econ Rev 88(3):628–642

Greenstein TN (1990) Marital disruption and the employment of married women. J Marriage Fam 52:657–676

Grossbard-Shechtman SA, Neuman S (1988) Women’s labor supply and marital choice. J Polit Econ 96(6):1294–1302

Henley A (2004) House price shocks, windfall gains and hours of work: british evidence. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 66(4):439–456

Huber J, Spitze G (1980) Considering divorce: an expansion of Becker’s theory of marital instability. Am J Sociol 86(1):75–89

Imbens GW, Rubin DB, Sacerdote BI (2001) Estimating the effect of unearned income on labor earnings, savings, and consumption: evidence from a survey of lottery players. Am Econ Rev 91(4):778–794

Joulfaian D, Wilhelm MO (1994) Inheritance and labor supply. J Hum Resour 29(4):1205–1234

Kabatek J (2019) Divorced in a flash: the effect of the administrative divorce option on marital stability in the Netherlands. IZA DP No. 12150

Kalmijn M, De Graaf PM, Poortman AR (2004) Interactions between cultural and economic determinants of divorce in the Netherlands. J Marriage Fam 66(1):75–89

Krueger AB, Pischke JS (1992) The effect of social security on labor supply: a cohort analysis of the notch generation. J Law Econ 10(4):412–437

Outes-Leon I, Dercon S (2008) Survey attrition and bias in young lives. In: Young lives technical note 5. Oxford: University of Oxford

Pasteau E, Zhu J (2018) Love and money with inheritance: marital sorting between labor income and inherited wealth in the modern partnership. In: Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Paper 23/2018

Pestel N (2017) Marital sorting, inequality and the role of female labour supply: evidence from East and West Germany. Economica 84(333):104–127

Piketty T (2014) Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pollak RA (2004) An intergenerational model of domestic violence. J Popul Econ 17(2):311–329

Poortman AR, Kalmijn M (2002) Women’s labour market position and divorce in the Netherlands: evaluating economic interpretations of the work effect. Eur J Popul 18(2):175–202

Reinhold S, Kneip T, Bauer G (2013) The long run consequences of unilateral divorce laws on children—evidence from SHARELIFE. J Popul Econ 26(3):1035–1056

South SJ (2001) Time-dependent effects of wives’ employment on marital dissolution. Am Sociol Rev 66(2):226–245

South SJ, Spitze G (1986) Determinants of divorce over the marital life course. Am Sociol Rev 51(4):583–590

Spitze G, South SJ (1985) Women’s employment, time expenditure, and divorce. J Fam Issues 6(3):307–329

Stark O, Nicinska A (2015) How inheriting affects bequest plans. Economica 82(s1):1126–1152

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2006) Bargaining in the shadow of the law: divorce laws and family distress. Q J Econ 121(1):267–288

Tzeng JM, Mare RD (1995) Labor market and socioeconomic effects on marital stability. Soc Sci Res 24(4):329–351

van der Klaauw W (1996) Female labour supply and marital status decisions: a life-cycle model. Rev Econ Stud 63(2):199–235

Waite LJ, Lillard LA (1991) Children and marital disruption. Am J Sociol 96(4):930–953

Winkels J, Withers S (2000) Panel attrition. In: Rose D (eds) Researching social and economic change: the uses of household panel studies. Routledge, London

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1802–1820

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees for all valuable advices. I also wish to thank Jochem de Bresser, Adrian Kalwij, Marike Knoef, Mariacristina Rossi, Arthur van Soest and Davide Vannoni for suggestions and support. I am also grateful to the participants of SEHO2019 (Lisbon) and SIE2019 (Palermo). Please note that part of this paper comes from my thesis dissertation, available at https://pure.uvt.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/28575968/PhDThesis_Basiglio.pdf

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basiglio, S. ‘Take the Money and Run’: Dutch Evidence on Inheritance and Transfer Receiving and Divorce. Ital Econ J 8, 585–605 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-021-00165-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-021-00165-0