Abstract

This paper investigates the bargaining agenda selection in a unionised duopoly with network effects. In contrast to the established result, in which under a pure monopoly the firm always prefers right-to-manage (RTM), it is shown that a sequential efficient bargaining (SEB) is preferred, provided that the network effect is sufficiently intense. Moreover, the monopolist may strategically commit either to the simultaneous efficient bargaining (EB), RTM or SEB to deter market entry, depending on the size of the fixed costs and the network intensity. The strengthening of the network effects has the following implications. First, the blocking agenda switches from EB/SEB (for low-/high-fixed costs of entry) to RTM. Second, high network intensity eliminates the possibility of using the negotiation agenda as a tool to create a barrier to entry. The duopoly under SEB always yields the most desirable social welfare level. However, the threatened monopoly may impede the achievement of the social first-best outcome due to the entry deterrence effect of the bargaining agenda’s strategic choice. The role of the network effect on welfare is various: high network intensity makes the desirable social outcome attainable. However, medium intensity of the network effect may lead to the least desirable welfare level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Network industries are among the fastest-developing sectors of advanced modern economics. Typical examples of network goods are telephone and software: it is natural to observe that the utility of a particular consumer from using a telephone or a piece of software increases with the number of other telephone or software users. The large-scale expansions of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets exemplify the increasing significance of those industries in day-to-day life.Footnote 1

In general, network goods are products in which the utility derived by one consumer/user increases with the number of other consumers/users of those goods, that is, the total sales of the goods enhance the welfare of each consumer (Katz and Shapiro 1985; Amir and Lazzati 2011). In addition, the number of other consumers/users of the product may directly affect the demand for the network goods also because it may speak for the product quality and availability of after-sale services for long-lasting consumers. Therefore, the consumers’ expectations about the total sales of the goods may in principle be affected by different mechanisms of output decisions and different production costs and thus by different labour market institutions.

Indeed, a central issue of labour market institutions in advanced economies is the selection of the bargaining agenda between firms and unions. Because of the interconnections between labour and product markets, the subject takes on considerable importance both for labour economics and industrial organization. The unionised firm literature presents the classical result that, when firms bargain only over wage and choose employment, i.e. according to the right-to-manage (RTM) model (e.g. Nickell and Andrews 1983), profits are higher than when they bargain also over employment, either simultaneously as in the efficient bargaining (EB) model (e.g. McDonald and Solow 1981) or sequentially as in the sequential efficient bargaining (SEB) model (Manning 1987a, b).

Dowrick (1990) first analysed the issue of the more profitable negotiation agenda in the context of unionised industries; this author has found “that profits under the Right-to-Manage model exceed those under Efficient Bargaining” (Naylor 2003, p. 59). Moreover, the negotiation outcomes of the RTM and SEB agendas have also been compared, and the conventional result of the established literature argues that “under unionized monopoly, the firm will prefer to keep employment off the bargaining agenda, whatever the degree of union influence over employment. In other words, the Right-to-Manage outcome generates higher profits than either the efficient or sequential bargains, for a given level of union influence over the wage” (Naylor 2003, p. 61). This is true particularly regarding a unionised monopoly in which strategic competitive effects are absent and thus wage costs (depending on the specific alternative bargaining arrangements) can never be used as a strategic device. Here, we first consider the monopoly case in which the network effects on the preference of the agenda cannot be obfuscated, with regard to the firm, by indirect strategic competitive effects.Footnote 2 Second, we analyse the case of monopoly with the threat of entry in which the network effects influence the preference of the agenda also through the strategic effects due to potential competition in both the product and labour markets.

The effects of firms’ strategic interaction and market entry on preferences over the bargaining agenda have been recently investigated by Bughin (1999), Vannini and Bughin (2000), Buccella (2011), (Fanti 2014, 2015) and Fanti and Buccella (2015). Moreover, it is natural to think that the choice of bargaining agenda may exert some influence on the behaviour of incumbents and entrants, although the investigation of this theme is rather scant. Nonetheless, the link between the presence of labour unions and the market structure and, consequently, the market entry, is rather relevant both on empirical (e.g. Chappell et al. 1992)Footnote 3 and theoretical grounds. In fact, from a theoretical perspective, a few articles have dealt with the presence of labour unions and entry such as Dewatripont (1987, 1988a, b), Ishiguro and Shirai (1998), Pal and Saha (2008), Mukherjee and Wang (2013). However, none of them have studied the choice of the bargaining agenda as an entry deterrence tool. Exceptions are Bughin (1999), Buccella (2011) and Fanti and Buccella (2015), in which the result that RTM dominates EB can be considered to be conventional in the pure monopoly, while in a monopoly with threat of entry, EB is predominant as a Nash equilibrium.

However, despite their relevance, all of those authors abstract from the possibility that goods in unionised industries present positive consumption externalities. Indeed, the presence of network effects is not innocuous. For instance, a recent growing body of literature has shown that network externalities may alter many established results of the industrial organization literature obtained basically by assuming non-network goods, especially in relation to oligopolies with managerial delegation (e.g. Hoernig 2012; Bhattacharjee and Pal 2014; Chirco and Scrimitore 2013).

The paper aims to consider the impact of the network effects on the preferences over the bargaining agenda first in the pure monopoly case (i.e., in the short run in the absence of firm competition) and then, in the long run, on the monopoly with the threat of entry when the strategic effects of potential competition are taken into account. In particular, the present paper attempts to answer the following questions: does the conventional result, that under pure monopoly a firm always prefers RTM to EB and SEB (with a corresponding conflict of interests between firm and union), hold true in the presence of network effects? What happens if there is the threat of market entry in the industry? May the incumbent still strategically select the EB agenda to deter entry? What are the consequences in terms of social welfare? The answers to these questions reveal that network effects may alter the established results of the previous literature.

As regards monopoly, our novel findings show that network effects matter. In fact, in contrast to the established result that a monopolist always prefers RTM, a SEB agreement is preferred, provided that the network effects are sufficiently intense (and the union’s bargaining power is not too high). Because the union and consumers always prefer the SEB agenda, the presence of network effects may solve the traditional conflict of interests between parties and achieve a Pareto-superior societal outcome.

We identify the following three effects of the network externalities related to the analysis of entry. First, when these externalities are sufficiently strong, the entry deterrence effect is always weakened, regardless of the bargaining agenda and the size of the fixed costs the entrant has to face. Second, as network externalities intensify, the entry deterrent agenda shifts from EB/SEB (in the case of low/high fixed costs of entry) to RTM. Third, for sufficiently high union bargaining power, a no univocal role of the network effect emerges. In fact, on the one hand, the presence of network effects allows the exploitation of the bargaining agenda for medium values of the network intensity; on the other hand, both relatively low and high values of the network effect facilitate the elimination of the agenda as a barrier to entry.

With regard to social welfare, the main results are as follows. The duopoly under the SEB agenda is always the most preferred bargaining institution from the society viewpoint. Nonetheless, the possibility that the bargaining agenda can be used as an entry deterrence tool impedes the achievement of the first-best social welfare. In this case, the role of the network effect is extremely various. In fact, if the intensity of the network is extremely high, the achievement of the desirable social welfare outcome is possible. However, if the network effect is of medium intensity, the entry is more likely to be deterred under the RTM agenda, which leads to the unwelcome result of reaching the least social welfare level.

Moreover, a number of testable hypotheses emerge from our analysis. In industries with sizable network externalities: (1) without the threat of entry, monopolists should prevalently choose an efficient bargaining arrangement, and (2) in the case of threat of entry: (2.1) when unions are strong, more competitive market structures should be prevalent both for low and high network effects; on the other hand, if the network effects are sufficiently strong but not too strong, a monopolistic structure should be relatively more often present, irrespective both of the size of the fixed costs and the type of bargaining agenda; (2.2) when unions are not strong, a monopolistic structure should be less common when network effects are very strong; and (2.3) the RTM should be the predominant bargaining agenda, especially when the fixed costs of entry are high.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents the basic monopoly-union bargaining model. Section 3 analyses the issue of potential entry and discusses the welfare implications. Finally, the last section summarises the main results and suggests directions for further research on the subject.

2 The Model

The simple mechanism of network effects here assumed is that the surplus that a firm’s client obtains increases directly with the number of other clients of this firm (i.e. Katz and Shapiro 1985). Following Hoernig (2012), Battacharjee and Pal (2014) and Chirco and Scrimitore (2013), the monopolist firm faces the following linear direct demand:

where q denotes the quantity of the goods produced, y denotes the consumers’ expectation about monopolist’s equilibrium production,Footnote 4 and the parameter \(n\in [0,1)\) indicates the strength of network effects (i.e., the higher the value of the parameter the stronger the network effects). The inverse demand function is:

where p is the price of goods. The monopolist’s profit function is:

where w is the wage per unit of output.

The efficient bargaining may be either simultaneous over wage and employment (EB) (McDonald and Solow 1981) or sequential, first over wage and then over employment (SEB) (Manning 1987a, b). In the cases of RTM and SEB, monopolist’s decisions are made in two stages. In the first stage, in the cases of both RTM and SEB, the monopolist-union unit bargains over wages w to maximise the Nash product. Then, following Katz and Shapiro 1985 and the above mentioned literature, we impose the additional “rational expectations” conditions, that is, consumers fulfil their expectations at equilibrium (i.e. \(y= q)\), in the second stage. In the third stage (1) with RTM, the monopolist chooses the quantity q (alternatively, the price p) to maximise profits and (2) with SEB, the monopolist-union unit negotiates over the quantity q (alternatively, the price p) to maximise the Nash product. On the other hand, under EB, the monopolist-union unit bargains simultaneously over wages w and quantity q to maximise the Nash product. As usual, our equilibrium concept is the subgame-perfect Nash equilibrium, and we solve this game using the backward induction method. Figure 1 summarises the timing of the game for each bargaining arrangement.

The union utility function is \(V=(w-w^{\circ })l\) (e.g. Pencavel 1985), where l is employment and w \(^{\circ }\) the reservation wage. Given the standard assumption of constant returns to labour, \(q=l\), it follows that

The bargaining solution is modelled by the following generalized Nash product

Using Eqs. (1)–(4) and solving the Nash product in Eq. (5), direct computations produce the expressions in Table 1. The Appendix provides the extensive derivations.

Based on the equilibrium outcomes for the alternative bargaining agendas in Table 1, we analyse the impact of the network effects in consumption.

Result 1 In a network industry:

the monopolist always prefers to bargain sequentially rather than simultaneously in the case of efficient bargaining. Moreover, it

-

1)

prefers SEB rather than RTM provided that the network effect is sufficiently high, and the lower the union’s power, the more likely a monopolist will be to prefer SEB;

-

2)

as expected, the union always prefers SEB rather than RTM. Otherwise, it may prefer SEB rather than EB, provided that its union’s power is high enough.

Proof

Given the outcomes in Table 1, we have:

-

1)

\(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}=(\pi ^{RTM}-\pi ^{SEB})=\frac{b(b-n(2-n))(2-b)^2(a-w^{\circ })^2}{4(2-n-b)^2(2-n)^2}\) from which it is directly obtained that \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}\frac{<}{>}0\;\Leftrightarrow \;1>n>n_1 =1-\sqrt{1-b} \); or, equivalently, that \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}\frac{<}{>}0\;\;\Leftrightarrow \;1>b>b_1 =1-(1-n)^2\), with \(\frac{\partial n_1 }{\partial b}>0\), \(\frac{\partial b_1 }{\partial n}>0\). It follows that the monopolist’s profit ranking is as follows: \(\pi ^{RTM}>\pi ^{SEB}\ge \pi ^{EB}\;\,\) \(if\;n=0; \quad \pi ^{RTM}>\pi ^{SEB}>\pi ^{EB} \quad if\;b>1-(1-n)^2;\pi ^{SEB}\ge \pi ^{RTM}>\pi ^{EB} \quad if\;b\le 1-(1-n)^2\);

-

2)

\(\Delta V^{RTM/SEB}<0;\;\Delta V^{EB/SEB}\frac{>}{<}0\;\Leftrightarrow b\frac{<}{>}\frac{2(2-n)}{4-n}\). It follows that the union utility ranking is: \(V^{SEB}\ge V^{EB}>V^{RTM}\;\, \quad if\;b\ge \frac{2(2-n)}{4-n};\) \(V^{EB}>V^{SEB}>V^{RTM}\;\, \quad if\;b<\frac{2(2-n)}{4-n}\).

Corollary 1

When network effects are sufficiently intense, the monopolist and the union agree on the SEB agenda.

Proof

From Result 1, it directly follows that, if \(1-(1-n)^2\ge \;b\ge \frac{2(2-n)}{4-n}\), the monopolist and the union prefer the SEB agenda. \(\square \)

Lemma 1

RTM and SEB wages are equal and lower than EB wages. Moreover, RTM and SEB wages are independent on n, while EB wages are increasing with n.

Proof

By simple inspection of the expressions for \(w^{RTM}\), \(w^{SEB}\) and \(w^{EB}\) in Table 1. \(\square \)

Result 1 and Lemma 1 contrast with the case of goods with no network effects in which the monopolist always gains larger profits with RTM rather than SEB and EB (Dowrick 1990), and profits under efficient bargaining are the same, regardless of whether the timing is sequential or simultaneous (Naylor 2003).

The economic intuition behind the above findings is that, in the presence of network externality, the profits with SEB are higher than EB, because the consumers’ expectations on the market size are not “known” when the wage is bargained at the first stage; thus, the SEB wage is independent of n. On the other hand, in the EB game, where the wage and employment are concurrently determined, the consumers’ expectations are so far realised, and the externality effect has a positive impact on the bargained wage. The economic rationale for this positive effect can be explained as follows. In contrast to SEB and RTM, under EB, the union knows the output (and, therefore, the employment) level inclusive of the externality effect on consumption. This is because consumers’ expectations are already realised when the wage is negotiated. As the consumption externality is simply the employment level itself (multiplied by n), then the union is able to negotiate a higher wage because the employment level is higher due to the network effect. Of course, the higher n is, the higher the employment and, thus, the bargained wage. As a consequence, it follows that \(w^{EB}>w^{SEB}\).

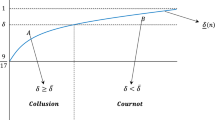

Figure 2 graphically illustrates Part 1 in Result 1, which reverses the conventional result with regard to the preferred agenda by firms and is worth to be commented more in detail. At first glance, the finding that \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}\frac{<}{>}0\) seems to be puzzling, because \(w^{RTM}=w^{SEB}\) while \(q^{RTM}<q^{SEB}\). Moreover, it is also valid that \(p^{RTM}>p^{SEB}\) in the [n,b]-space. Closer analytical inspection reveals that the monopolist, in equilibrium, produces at a point on the demand curve where the price elasticity of demand is larger under RTM than SEB, that is, \(\varepsilon ^{*RTM}(n,b)>\varepsilon ^{*SEB}(n,b)\). Depending on the values of [n,b], the elasticity (and mark-up) differential may increase or decrease; as a consequence, the price effects may dominate or not the quantity effects on the monopolist revenues. Figure 2 tells us that when \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}>( <) 0\), the price effect dominates (is dominated by) the effect on quantity variation.Footnote 5

Result 2 Consumers and society always prefer SEB rather than EB and RTM.

Proof

Simple comparison of the payoffs in Table 1 leads to the following rankings: \(CS^{SEB}>CS^{EB}>CS^{RTM}\Leftarrow \;n>0;SW^{SEB}>SW^{EB}>SW^{RTM}\Leftarrow \;n>0.\) \(\square \)

Result 3 Provided that the network effect is sufficiently high, the SEB arrangement is Pareto-superior (i.e. monopolist, workers and consumers prefers it). The proof directly follows from the previous results.

To sum up, network effects may be responsible for the elimination of undesirable conflicts regarding the bargaining agenda between parties and the occurrence of a Pareto-superior outcome.

3 Monopoly with Threat of Entry

In the previous subsections, we have analysed the preferences over the bargaining agenda of the monopolist and its union; however, we have considered the monopoly as the given market structure. In the following, we investigate the topic of the bargaining agenda selection in the context of market entry under consumption externalities.

In the traditional case of standard goods (i.e. without network effects) the strategic choice of the bargaining agenda for different market structures, namely duopoly vs. (pure or threatened) monopoly, has been studied by Bughin (1999), Buccella (2011), and more recently Fanti and Buccella (2015). Bughin (1999) and Buccella (2011) consider that the institutional arrangements in the labour market are the EB and the RTM agenda. They analyse different entry modes and constraints on the choice of bargaining scope: (1) committed bargaining, in which the incumbent firm chooses the bargaining agenda, and then the entrant “joins the pack” and adopts the agenda of the incumbent, and (2) flexible bargaining, in which the entrant freely chooses the agenda. Fanti and Buccella (2015) extend the previous literature to different timing specifications of the bargaining game.

The key results of Bughin (1999) are as follows: (1) in a duopoly with committed bargaining, firms prefer to bargain under RTM rather than EB, in clear conflict of interest with unions; (2) in the case of potential entry with committed bargaining, the incumbent can choose EB over RTM to deter the market entry of a potential competitor if the union has adequately low bargaining power. Using a conjectural variation model, Buccella (2011) confirms the results of Bughin (1999). Moreover, in a Cournot duopoly extended to the SEB agenda, Fanti and Buccella (2015) additionally find that SEB can also be used to deter entry in the case of committed bargaining.Footnote 6

In the present paper, we consider the three institutional arrangements of RTM, EB and SEB as in Fanti and Buccella (2015); however, for simplicity, we restrict the analysis to the case of monopoly with threat of entry with committed bargaining. We extend the previous work to the presence of consumption externalities (network effects) to investigate how those externalities modify the possibility that the bargaining agendas may be effective as a strategic deterrence tool.

3.1 Game Framework

Let us first consider the game’s framework and structure. The game, as usual, is solved via backward induction to derive sub-game perfect Nash equilibria. The first three stages are common to each arrangement. In the first stage, the incumbent firm-union unit chooses the bargaining agenda to introduce (RTM, SEB or EB). In the second stage, the entrant, taking into consideration its fixed costs, decides whether to enter the industry. Whenever entry is allowed, in the third stage, the entrant firm-union pair “joins the pack” and adopts the agenda of the incumbent pair. In the last stages, depending on the agenda, the sequence of moves is as follows. In the case of RTM and SEB, in the fourth stage, each firm-union bargaining unit simultaneously negotiates over wages, and then, in the fifth stage of the game, consumers fulfil their expectations. In the sixth and last stage of the game, firms compete in the product market and simultaneously select their output level (given the optimal wages bargained with the unions). However, under SEB, each union-firm pair bargains the employment level, taking into consideration the optimal wage previously bargained with the union and the market interaction with the rival firm. In the case of EB, in the fourth stage, consumers fulfil their expectations and, in the fifth and last stage of the game, each union-firm unit simultaneously negotiate the wages and employment, taking into account the product market interaction with the rival. Note that, under EB, in contrast with both RTM and SEB cases, the wage bargaining occurs contingent on the knowledge of the fulfilment of the consumers’ expectations in the preceding stage. Figure 3 summarises the timing of the game for each bargaining arrangement.

We define firm 1 as the incumbent and firm 2 as the potential entrant. In duopoly, the demand function becomes

The firms’ profit functions are

for the incumbent and the entrant, respectively. The term E represents an exogenous fixed cost that the entrant faces.

On the other hand, the union utility function is

The bargaining solution is now modelled by the following generalized Nash product:

Using Eqs. (6)–(9) and solving the Nash product in Eq. (10), straightforward calculations provide the expressions in Table 2. The Appendix provides the extensive derivations.

3.2 The Selection of the Agenda as Barrier to Entry

Let us consider the incumbent’s selection of the bargaining agenda as a strategic deterrence tool. To deter entry, the incumbent compares its monopoly profits with the duopoly profits after entry under the alternative agendas, taking into consideration the fixed costs of the competitor in the industry. Table 3 reports the payoffs. A closer analytical observation leads to the following result.

Result 4 The firm’s payoffs in Table 3 generate Fig. 4, characterised by thirteen regions in the relevant [n,b]-space.

Proof

See the Appendix

Following the reasoning of Bughin (1999), Buccella (2011) and Fanti and Buccella (2015), in the case of monopoly with threat of entry under “committed bargaining”, the incumbent firm (M) can strategically choose the bargaining agenda as an entry deterrence tool.

In the subsequent analysis, we impose the following restriction on the size of the fixed costs the entrant has to face.

Restriction 1 \(\max \pi _1^{i/D} {>}E{>}\min \pi _1^{j,k/D} ,\;i,j,k={} { RTM,SEB,EB}\; i\ne j,k\).\(\square \)

The economic meaning of Restriction 1 is straightforward: in fact, if \(\min \pi _1^{i/D} >E\), the fixed costs are extremely low, such that there is always free entry in the industry; in contrast, if \(E>\max \pi _1^{i/D} \), the size of the fixed costs is severely high for the potential competitor for which the market entry is always blockaded. Given Restriction 1, the incumbent firm strategically chooses the use of a precise bargaining agenda to deter entry if the following conditions apply:

Let us discuss conditions (a)–(c) in (11). Condition (a) simply states that, with committed bargaining, if the incumbent negotiates with the union under a precise agenda, fixed costs are higher than the duopoly profits under that agenda to block the potential competitor, because entry would be not profitable. Condition (b) specifies that the duopoly profits with the alternative agendas do not have to be larger than the monopoly profits of the selected agenda because, otherwise, the incumbent finds it more profitable to select one of the alternative agendas and accommodate entry. Condition (c) determines that, if more than one agenda complies with (a)–(b), the incumbent selects the agenda, which ensures the highest profits.

Application of conditions (a)–(c) in (11) under Restriction 1 to Result 4 leads directly to Result 5.

Result 5 The following holds:

-

a)

depending on the size of the fixed costs E , the incumbent firm in an industry with network effects may use at least one bargaining agenda to deter entry unless the union bargaining or the network effects are adequately high;

-

b)

if the union bargaining power is not too high and E is sufficiently low, the incumbent in an industry with network effects may use the EB agenda to deter entry for a wide range of the network externalities. However, the higher the network externality, the lower the possibility is to use the EB agenda;

-

c)

if E becomes adequately high, the EB agenda as an instrument to deter entry is replaced by SEB for low-medium and RTM for medium-high values of the network effects.

Proof

See the Appendix. \(\square \)

Figure 5 graphically depicts Result 5, which call for some brief comments. First, the incumbent can no longer strategically select a bargaining agenda to block entry to intensive network effects. This result is independent of the fixed costs’ size. Second, depending on the size of E, different bargaining agenda can strategically be used as a deterrence tool. In the case of low fixed costs (see left box, Fig. 5), EB prevails to prevent entry; however, it is not the unique agenda that can be exploited. In fact, there are two regions in the parameter space where also SEB and RTM can deter market entry. On the other hand, in the case of high fixed costs (see right box of Fig. 5), although EB might be potentially used as a barrier to entry, the incumbent never selects EB because it always finds it profitable to commit to SEB (for low-medium values of the network intensity) and RTM (for medium-high values of the network intensity) negotiations as deterrence tools.Footnote 7

Thus, the presence of the network effects strongly enriches and modifies the core results of Bughin (1999), Buccella (2011) and Fanti and Buccella (2015), according to which EB is the sole agenda to be used as an entry deterrent: in fact, on the one hand, the effectiveness of using EB to block entry in a unionised industry decreases as the network externality increases, and on the other hand, the RTM agenda may also be a strategic deterrence tool. More in general, the role of the network effect is to weaken the strategic use of the negotiation agendas as a barrier or even to eliminate any agenda as an entry barrier for low levels of the union’s power.Footnote 8

Therefore, this analysis evidences a crucial role of the network externalities. In particular, three major effects of the network externalities need to be highlighted. First, regardless of the size of the entry costs the potential competitor has to face, the network externalities always work in the direction of reducing the strength of the deterrence effect. Second, the strengthening of the network effects implies that the blocking agenda switches from EB/SEB (for low/high fixed costs of entry) to RTM. The rationale for this finding can be explained as follows. In general, more intensive network effects work in the direction of making the EB/SEB monopoly profitability (for low/high fixed costs of entry) higher than the RTM duopoly. In fact, the monopoly wage under SEB is independent of the parameter n, while network externalities have a higher positive impact on RTM than EB wages. However, when network externalities are not too intense, the EB/SEB duopoly profits are lower than RTM. This result occurs because the positive impact of the network effects on EB/SEB duopoly prices does not overcome those effects on wages. As a consequence, the critical value of the fixed cost for the entrant under RTM is higher than EB/SEB, and the incumbent can strategically commit to the latter agendas to deter entry. This status changes when the network effects become sufficiently high; their positive impact on EB/SEB duopoly prices overcome that on wages, and the overall profitability of those agendas is higher than that on RTM. Therefore, the fixed cost threshold for the entrant under EB/SEB increases, and the incumbent can strategically select RTM to deter market entry.

Third, for adequately high values of the union bargaining power, a no univocal role of the network externalities arises. In fact, relatively low/high values of the network effect act in the opposite direction and eliminate the possibility of using the negotiation agenda as a tool to create a barrier to entry while the network effects allow the use of the bargaining agenda to deter entry only for medium values of the network intensity.

To sum up, network effects play an important role on entry.Footnote 9

3.3 Welfare Considerations

Let us consider the welfare effects of the proposed model. A wide characterisation of the effects of the network externalities on social welfare was largely unexplored. Given the social welfare payoffs in Tables 1 and 2, a straightforward analytical inspection reveals the following result.

Result 6 A duopoly with SEB always leads to optimal social welfare outcome.

Proof

See the Appendix. \(\square \)

Let us first consider the welfare effects of the entry game with committed bargaining.Footnote 10

Result 5 states that, in an industry with consumption externalities, the monopolist can strategically select the appropriate bargaining agenda to deter entry except for values sufficiently high of the union bargaining and network effects. Figure 6 shows the social welfare regions generated by Result 6. Figure 7 overlaps the parameters’ space in which Results 5 applies (i.e. Fig. 5) at the social welfare regions of Fig. 6 (bold lines). In the case of low fixed costs, EB deters entry for low-medium values of the union bargaining power. However, the presence of network effects reduces the opportunity to block entry with respect to standard goods. A straightforward graphical inspection of Fig. 7 reveals that, in the presence of low fixed costs of entry, the region in which EB blocks entry falls in Regions IV and V, reported in the proof of Result 6 in the Appendix and graphically depicted in Fig. 6.

Consequently, the society ends up with the second-last welfare level. In the area where SEB blocks entry, which partially covers Regions I–V of the social welfare ranking in the proof of Result 6 reported in the Appendix, the entry deterrence is not strictly welfare detrimental (the monopoly profits under SEB are higher than the duopoly profits under EB and RTM), except for the small welfare detrimental triangle area, which falls into Region V. In fact, SEB allows reaching either the second-best (Regions II and III)Footnote 11 or the third-best outcome (Region IV). On the other hand, when the fixed costs are high, the area in which EB blocks entry is replaced by SEB/RTM for low-medium/medium-high values of the network intensity.

These findings confirm and broadly extend the insight of Fanti and Buccella (2015), who challenge the idea that the efficient bargaining agenda, both in the simultaneous and sequential mode, is socially efficient due to its potential deterrence effect in a long-run perspective; i.e. when potential entry is allowed. In this respect, Fig. 8 depicts the rather complicated area representing the parameter space in which the strategic use of the bargaining agendas is welfare damaging in the presence of low/high fixed costs.

From Result 5 we also know that there are two areas in which the incumbent cannot strategically select any negotiation agenda to deter entry: when the union bargaining power is sufficiently high (with enlarging ranges of n as b approaches the unity) and when network effects are relatively intense (with enlarging ranges of b towards the extreme values when n approaches the unity). From Result 6, the government has a clear indication in those areas; a duopoly with SEB ensures the overall highest welfare level.

Thus, we observe that the role played by the network effect on welfare is not unambiguous. In fact, if the network effect is extremely high, the most desirable social welfare outcome can be attained. However, if the network effect is of medium intensity, the RTM agenda may deter market entry, especially in the presence of high fixed costs, therefore leading to the unwelcome result of reaching the least social welfare level. In particular, from a social welfare point of view, a range exists of medium-high levels of the network effects around the value of \(n=.7\), such that the monopolist can virtually always deter entry with the RTM agenda for every value of the union bargaining power, thus entrapping the economy in the least social outcome.

Note that the welfare-damaging parametric area is slightly reduced in the case of high fixed costs (as easily seen by observing the left and right boxes of Fig. 8).Footnote 13

4 Conclusions

In this paper we have examined the issue of the bargaining agenda in the presence of network goods. First, we have analysed a unionised pure monopoly, and then a monopoly with the threat of entry when the strategic effects of potential competition are taken into account. The key message is that different labour market institutions add to the other known devices used as a barrier to entry in network industries (i.e. capacity investment, patents, limit prices and so on).

With regard to pure monopoly, we have shown that the monopolist’s preferred agenda depends crucially on the strength of the network externality. While without network effects profits under the RTM arrangement are always higher than EB/SEB (both modes yield the same bargaining outcome), we show that the monopolist prefers the SEB agenda with network externalities, especially when the union bargaining power is low. This result is due to the sequential negotiation for which the consumers’ expectations on the market size are not already realised in the long run; i.e. in the first stage of wage determination. Moreover, given that the union and consumers always prefer the SEB agenda, network externalities may partly solve the traditional conflict of interests between the bargaining parties and lead to the Pareto superior equilibrium.

With regard to monopoly with the threat of market entry under “committed bargaining”, we have shown that, if the incumbent can choose the negotiation agenda, it may commit to different agendas to prevent the entry of a potential competitor. The choice crucially depends on the size of the fixed costs the entrant has to face, the strength of the network externality and the union bargaining power. In particular, when the fixed costs are sufficiently low, the incumbent may use EB to block entry for a wide range of the network externalities and the union bargaining power. For medium-high values of the union power (and increasing values of the network externalities), SEB can be used as an entry deterrent, while, for medium-high values of network effects (and values tending to the extremes of the union power), RTM prevails. If the fixed costs are sufficiently high, SEB for low-medium and RTM for medium-high values of the network effects replace EB as an entry deterrent instrument. However, regardless of the fixed costs’ size, when the network effects are adequately intense, no agenda deters entry, eliminating the barrier to entry.

With regard to social welfare, we have shown that the duopoly under SEB leads always to the most desirable social welfare level. However, the possibility of the monopolist of using the bargaining agenda as an entry deterrent harms the achievement of the social optimum outcome. The role of the network externalities is not clear cut. In fact, if the network intensity is high, it is possible to attain the desirable social welfare outcome. On the other hand, for medium intensity of the network effect, the entry is more likely to be deterred under the RTM agenda with welfare-detrimental outcome effects. On the whole, the SEB agenda seems to ensure, in most of the cases, the best affordable welfare outcomes.

These findings offer the policy implication that decision makers should pay attention both to the bargaining agenda and the intensity of consumption externalities. Thus, to achieve the highest welfare level, in terms of policy, the governments should operate to introduce and further encourage SEB agreements in network industries only if unions and the network effects are very strong. Otherwise, our findings have shown all of the other parameters’ combinations that lead to sub-optimal (for instance, third-best and even least) welfare outcomes associated with the bargaining agendas and the relative market structures that arise in equilibrium. Moreover, the governments have to promote, if possible, the increase of the network effects beyond a certain high threshold (especially when unions are not too strong) to allow a more competitive industry structure.

A reasonable further step for future research would be to analyse whether a monopoly firm should hire a manager to bargain with the union and, if it is the case, how the findings of this paper may change. The entry game should be extended, allowing for the “flexible” commitment. Finally, an interesting extension of this analysis could be to investigate from a game-theoretic perspective the selection of the bargaining agenda in a duopoly market structure with price competition and differentiated products.

Notes

More generally, positive network externality may exist for those products which a consumer wishes to possess in part because others do (i.e. the so-called Bandwagon Effect), for instance products of the fashion industry.

Other conventional results of the unionised firm literature are that (i) unions always prefer the EB agenda and thus a (possibly undesirable) conflict of interest between the bargaining parties always occurs (Bughin 1999; Buccella 2011) and (ii) duopoly is always socially preferred to monopoly, also with unionised labour markets.

In fact, Chappell et al. (1992) find a statistically significant relationship between unionisation and entry deterrence with the US data.

Note that we strictly follow here the assumptions of Katz and Shapiro (1985) and the recent literature above mentioned in the main text. However, as also noted by Katz and Shapiro (1985, Appendix A), and Amir and Lazzati (2011), in some contexts, firms may be able to commit strongly to an output level before consumers make their purchase decisions (only the equilibrium output levels are credible announcements). In such cases, the effect of output decisions by the monopolist without expectations, or, in the case of duopoly considered in Sect. 3, by each firm under the given expectations regarding only the consumers of the rival firm’s product rather than under the expectations regarding both products’ consumers, which may lead to different equilibrium outcomes. A sketched treatment of this case is shown in Appendix 4. We also thank an anonymous referee for having suggested the possible presence of this case.

Analytically, we can describe this result as follows. Let us define the additional marginal revenues differential under the two bargaining agendas as \(\Delta R=[(MR^{RTM}dq^{RTM}-MR^{SEB}dq^{SEB})]\). The latter expression can be developed and re-arranged in the following way: \(\Delta R(n,b)=\left[ {(p^{RTM}(n,b)-p^{SEB}(n,b))+( {\frac{dp^{RTM}(n,b)}{dq^{RTM}(n,b)}q^{RTM}(n,b)-\frac{dp^{SEB}(n,b)}{dq^{SEB}(n,b)}q^{SEB}(n,b)})} \right] (dq^{RTM}-dq^{SEB})\). Figure 2 shows that in the area of the \((n,b)-\)space where \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}>(<)0\), the combination of the parameters is such that the price differential effect between the two agendas dominates (is dominated by) the effect on the quantity variation.

Fig. 2 Plot of the “threshold curve” \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB} = 0\) in [n,b]-space. The curve is drawn for a = 1, w\(^{\circ }\) = 0. For all [n, b] combinations along the curve \(b=1-(1-n)^2\), \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}=0\) holds true. For all [n, b] combinations above (below) the curve, profits are higher under RTM (SEB) arrangement (that is, \(\Delta \pi ^{RTM/SEB}>( <) 0)\)

Note that we use the term ‘entry deterrence’ as usual in the static one-period frame (e.g., Bughin 1999). Of course, a more general way to deal with the effectiveness of tools of entry deterrence would require a real-time structure with, for instance, technology changes or investment decisions.

It is easy to see in Fig. 4 that, if the fixed costs become adequately high, both agendas extend their areas of deterrence application into the area formerly occupied by the EB agenda, (SEB for low values of the network intensity, RTM for high values).

For instance (see Fig. 4), when \(n=0\) SEB and EB are chosen to deter entry if \(b\le 0.73\) but when \(n=0.9\), EB is selected only for \(b<0.18\).

Note that the results of Fanti and Buccella (2015) presented at the beginning of Sect. 3 in relation to the issue of entry hold only in Region IX, defined in the proof of result 4, reported in the Appendix and graphically depicted in Fig. 4. In all the other regions, the results differ from those authors precisely because of the network effects analysed in the current paper.

Needless to say, the first best outcome in a strict sense is prevented in this framework because of the imperfect competition both in the product and labor markets.

Since the conventional wisdom would argue that the higher the fixed costs, the more likely welfare is to be reduced due to the prevented entry, thus this result may appear rather counterintuitive, and this provides additional evidence of the complex interactions between the bargaining agendas and network effects.

All the regions in the proof of Result 5 are related to the areas in Fig. 4 and the payoffs’ rankings in the proof of Result 4.

Note that output decisions are taken by each firm under given expectations only as regards the consumers of the rival firm’s product. This amounts to say that each firm knows that own consumers take into account the own output commitment but it does not know the expectations of the customers as regards the product of the rival firm.

References

Amir R, Lazzati N (2011) Network effects, market structure and industry performance. J. Econ. Theory 146(6):2389–2419

Bhattacharjee T, Pal R (2014) Network externalities and strategic managerial delegation in Cournot duopoly: Is there a prisoners dilemma? Rev. Netw. Econ. 12(4):343–353

Bughin J (1999) The strategic choice of union-oligopoly bargaining agenda. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 17:1029–1040

Buccella D (2011) Corrigendum to “The strategic choice of union oligopoly bargaining agenda” [Int. J. Ind. Organ. 17 (1999) 1029–1040]. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 29:690–693

Cellini R, Lambertini L, Ottaviano M (2004) Welfare in a differentiated oligopoly with free entry: a cautionary note. Res. Econ. 54:125–133

Chappell WF, Kimenyi MS, Mayer WJ (1992) The impact of unionization on entry of firms: evidence from US industries. J. Lab. Res. 13(3):273–283

Chirco A, Scrimitore M (2013) Choosing price or quantity? The role of delegation and network externalities. Econ. Lett. 121:482–486

Dewatripont M (1987) Entry deterrence under trade unions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 31(1/2):149–156

Dewatripont M (1988a) Commitment through renegotiation-proof contracts with third parties. Rev. Econ. Stud. 55(3):377–389

Dewatripont M (1988b) The Impact of Trade Unions on Incentives to Deter Entry. RAND J. Econ. 19(2):191–198

Dowrick S (1990) The relative profitability of Nash Bargaining on the labour demand curve or the contract curve. Econ. Lett. 33(2):121–125

Fanti L (2014) When do Firms and Unions agree on a Monopoly Union or an Efficient Bargaining Arrangement? Discussion Paper n. 181. Department of Economics and Management, University of Pisa

Fanti L (2015) Union-firm bargaining agenda: right-to-manage or efficient bargaining? Econ. Bull. 35(2):936–948

Fanti L, Buccella D (2015) Bargaining Agenda, Timing, and Entry. MPRA Working Paper Series n. 64089

Hoernig S (2012) Strategic delegation under price competition and network effects. Econ. Lett. 117(2):487–489

Ishiguro S, Shirai Y (1998) Entry deterrence in a unionized oligopoly. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 49(2):210–221

Katz M, Shapiro C (1985) Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am. Econ. Rev. 75(3):424–440

Mankiw NG, Whinston MD (1986) Free entry and social inefficiency. RAND J. Econ. 17:48–58

Manning A (1987a) An integration of trade union models in a sequential bargaining framework. Econ. J. 97:121–139

Manning A (1987b) Collective bargaining institutions and efficiency. Eur. Econ. Rev. 31:168–176

McDonald IM, Solow RM (1981) Wage bargaining and employment. Am. Econ. Rev. 71(5):896–908

Mukherjee A, Wang LFS (2013) Labour Union. Entry and Consumers Welfare. Econ. Lett. 120(3):603–605

Naylor RA (2003) Economic Models of Union Behavior. In: Addison J.T., Schnabel, C. (eds) International Handbook of Trade Unions. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 44–85

Nickell SJ, Andrews M (1983) Unions real wages and employment in Britain 1951–79. Oxford Economic Papers 35, pp 183–206 (supplement)

Pal R, Saha B (2008) Union-oligopoly bargaining and entry deterrence: a reassessment of limit pricing. J. Econ. 95:121–147

Pencavel JH (1985) Wages and employment under trade unionism: microeconomic models and macroeconomic applications. Scand. J. Econ. 87:197–225

Vannini S, Bughin J (2000) To be (unionized) or not to be? a case for cost-raising strategies under Cournot oligopoly. Eur. Econ. Rev. 44:1763–1781

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Roberto Cellini, Editor of this Journal, and two anonymous referees for their extensive and helpful comments and suggestions that have considerably improved the quality of this paper. Domenico Buccella would also like to thank the Kozminski University in Warsaw for the support provided. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was not funded by any Institution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Monopoly Outcomes in the Cases of RTM, SEB and EB

1.1 RTM Institution

At stage 3, solving the monopolist’s profit maximisation problem, we obtain the following output function, for given consumers’ expectations:

Solving (12) by imposing the “rational expectations” condition,\( y=q\), the equilibrium quantities at stage 2 are:

At the first stage of the game, under RTM, the monopolist - union bargaining unit selects w to maximise the following generalised Nash product,

where b represents the union’s bargaining power.

After substitution of (13) in (14), maximisation of (14) w.r.t. w leads to:

Thus, the equilibrium outcomes are

Given (15) and (16), it is straight forward to derive all the expressions in Table 1.

1.2 Efficient Bargaining Institution

Under efficient bargaining the monopolist-union bargaining unit maximises the following generalised Nash product,

1.2.1 Sequential Efficient Bargaining

At third stage, from the first-order condition (FOC) of the efficient bargaining game between monopolist and union, one gets the monopolist’s output function:

From (18), after imposing the “rational expectations” condition in the second stage, we obtain the output level for given w:

In the first stage, after substitution of (19) in (17), the usual maximisation procedure w.r.t. w leads to

The equilibrium outcomes are

Given (20) and (21), all the expressions in Table 1 can directly be obtained.

1.2.2 Simultaneous Efficient Bargaining

From the system of FOCs of the EB game in (17) between monopolist and union, we obtain at the third stage:

After imposing the “rational expectations” condition at the second stage, and solving the system (22), (23), we obtain the following wage and output, respectively:

Given (24) and (25), all the other equilibrium outcomes reported in Table 1 in the main text are easily obtained.

Appendix 2: Duopoly Outcomes in the Cases of Committed RTM, SEB and EB

1.1 Duopoly with RTM

Given Eq. (6), the firms maximization problem under RTM, taking into consideration the additional “rational expectations” conditions, i.e. \(y_i =q_i ,\;i=1,2\), lead to the reaction functions

Solving the system of equations in (26), the firms’ output decision as function of the wages are

At the previous stage of the game, under RTM, each firm-union bargaining unit chooses w to maximise the following generalised Nash product,

where b represents the union’s bargaining power. After substitution of (27) in (28), maximisation of w.r.t. w leads to:

Solving the system of equations in (29), the equilibrium wage is

Further substitutions lead to the following equilibrium output

Given (30) and (31), direct calculations lead to all the expressions in Table 2.

1.2 Duopoly with Efficient Bargaining Institution

In the presence of the efficient bargaining institution, each firm-union pair maximises the following generalised Nash product,

Thus, each firm-union pair negotiates (1) in the case of SEB, first \(w_i \) and then \(q_i \); (2) in the case of EB, simultaneously \(w_i \) and \(q_i \).

1.2.1 Sequential Efficient Bargaining

In the last stage, the FOC of the efficient bargaining game between each firm and its union leads to the reaction functions

From (33), after imposing the “rational expectations” condition, we obtain the output level for given \(w_i \):

In the first stage, after substitution of (34) in (32), the usual maximisation procedure w.r.t. \(w_i \) leads to

Solving for \(w_i =w_j =w^{SEB/D}\) the system of eq. in (35), the equilibrium wage is

and, consequently, the equilibrium output

1.2.2 Simultaneous Efficient Bargaining

From the system of FOCs of the EB game in each firm/union pair, we obtain:

After imposing the “rational expectations” condition \(y_i =q_i ,\;\;i=1,2\), and solving the system (38), (39), we obtain the following wage and output at equilibrium, respectively:

Given (40) and (41), the equilibrium outcomes in Table 2 are obtained.

Appendix 3: Proofs of Results 4, 5 and 6

Proof of Result 4 The firm’s payoffs in Table 3 generate thirteen regions in the relevant [n,b]-space in which the payoff ranking is as follows:

Region I: \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region II: \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region III: \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region IV: \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region V: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region VI: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region VII: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region VIII: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region IX: \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region X: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region XI: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region XII: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \);

Region XIII: \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \).

Let us discuss, for matter of comparison, the case of \(n=0\) . From Result 4, it is immediately derived (see the ranking of Regions I and IX) that \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \) for \(0\le b\le 1\) : RTM always ensures the highest profits against the duopoly outcomes under SEB and EB. However, in Region I, condition (11) is not met because \(\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} \) : if the monopolist commits to RTM, it cannot prevent entry. Moreover, \(\pi _1^{RTM/D} >{\pi } _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} \): the monopolist has no incentive to change the bargaining agenda to deter entry. On the other hand, in Region IX, condition (11) holds, and simple calculations shows that, for \(b\le .73\), \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} =\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} \): the monopolist can commit only to the EB agenda to deter a potential entry with RTM.

Proof of Result 5 To prevent entry, under Restriction 1, (a)–(b) of condition (11) must be satisfied. If more than one agenda fulfils (a)–(b) in (11), then (c) provides the selection rule. In Region IFootnote 14 characterised by medium-high union bargaining power and low-medium network effects, the profits payoff ranking for the incumbent firm is \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \). Therefore, given Restriction 1, \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{RTM/D} )\). If the size of the fixed costs is such that \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), only EB meets part (a) of condition (11); however, part (b) is not satisfied. If the fixed costs increase to \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >E>\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), EB and SEB satisfy (a) but none fulfil (b) (because \(\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} )\). If the size of the fixed costs is \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >E>\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), only SEB satisfies (a) but it does not meet (b). When the fixed costs reach the maximum value such that entry is not always blockaded, no agenda meets (a)–(b) in (11). As a consequence, no agenda can strategically be selected by the incumbent to prevent entry.

A similar reasoning applies to Region II and, given the payoff structure in that area, it is easy to check that again no bargaining agenda can be used as entry deterrence tool. Summing up, when the union is extremely strong, no agenda can be selected to prevent entry virtually for all levels of the network effect.

In Region III, under Restriction 1, \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{RTM/D} )\). If the fixed cost are such that \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), EB is the unique agenda that fulfils (a) in (11); however, EB does not meet (b) in condition (11). If the size of the fixed costs is \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >E>\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), both EB and SEB meet (a) in condition (11) but only SEB satisfies (b): the incumbent can select SEB to deter entry because it ensures a higher payoff than SEB. When \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), the latter result remain unaltered.

Given the payoff structure of Regions IV, V and VI, the reasoning of Region III also holds in those Regions. Thus, for medium-high union bargaining power and with network effects, SEB can be used as entry deterrence tools.

In Region VII, Restriction 1 tells us that \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{SEB/D} )\). If the fixed cost are such that \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), the EB agenda meets (a) but not (b) in condition (11); all the other agendas do not satisfy neither (a) nor (b). If the fixed costs are \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), the latter result remains unchanged. However, if \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \) RTM satisfies (a) and (b) in (11): the incumbent can negotiate under RTM to block entry.

Region VIII is characterised by high network effects and medium-high union bargaining power. Restriction 1 implies that \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{SEB/D} )\). Thus, if the fixed costs are such that \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), under committed bargaining only the EB agenda fulfils (a) condition in (11); however (b) is not met. When \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), the latter result is unchanged. However, for \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >E>\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), the RTM agenda meets (a) but not (b) in (11); therefore, it cannot be used to deter entry. If the size of the fixed costs is \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), RTM fails to meet both (a) and (b) in (11). Consequently, no bargaining agenda can be used to deter entry.

In Region IX, characterised by low network effects and low/medium-high union bargaining power, it is easily verified that Restriction 1 leads to \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{RTM/D} )\). If the fixed costs are such that \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), EB meets (a) and (b) in condition (11). Therefore, EB can be used to deter entry. However, if \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >E>\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), now both SEB and EB satisfy (a) and (b) in (11). However, in this case with high fixed costs of entry, (c) is the rule for the agenda selection: the incumbent chooses SEB because \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} \). Given the payoff structure in Region X, a similar reasoning leads to the same result of Region IX: only the EB agenda blocks entry for a low value of the fixed costs; both SEB and EB deter entry for a high value of the fixed costs, but SEB is preferred because is more profitable than EB.

In Region XI, characterised by network effects medium/high and union power low/medium-high, Restriction 1 implies that \(E\in (\pi _1^{EB/D} ,\pi _1^{SEB/D} )\). Nonetheless, if \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >\pi _1^{RTM/D} >E>\pi _1^{EB/D} \), only EB meets (a) and (b) in condition in (11). Therefore, for low values of the fixed costs, EB can be used to deter entry. However, if \(\pi _1^{SEB/M} >\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} >\pi _1^{SEB/D} >E>\pi _1^{RTM/D} >\pi _1^{EB/D} \), now both RTM and EB can be used by the incumbent to deter entry. Thus, for high fixed costs, (c) determines which agenda is selected and, given that \(\pi _1^{RTM/M} >\pi _1^{EB/M} \), the incumbent chooses RTM because more profitable than EB.

Finally, given the payoff structure of Region XII, the findings mirror those of Region VII and RTM blocks entry in the industry; in Region XIII, characterised by high intensity of the network effect and low bargaining power, given the firms’ payoff structure, the results mimic those of Region VIII and no bargaining agenda can be used to deter entry.

Proof of Result 6 The payoffs in Tables 1 and 2 in relation to the social welfare generate five Regions in the relevant [n,b]-space, as shown in Fig. 6, in which the ranking is:

Region I: \(SW^{SEB/D} >SW^{EB/D} >SW^{SEB/M} >SW^{EB/M} >SW^{RTM/D} >SW^{RTM/M} \);

Region II: \(SW^{SEB/D} >SW^{SEB/M} >SW^{EB/D} >SW^{EB/M} >SW^{RTM/D} >SW^{RTM/M} \);

Region III: \(SW^{SEB/D} >SW^{SEB/M} >SW^{EB/D} >SW^{RTM/D} >SW^{EB/M} >SW^{RTM/M} \);

Region IV: \(SW^{SEB/D} >SW^{EB/D} >SW^{SEB/M} >SW^{RTM/D} >SW^{EB/M} >SW^{RTM/M} \);

Region V: \(SW^{SEB/D} >SW^{EB/D} >SW^{RTM/D} >SW^{SEB/M} >SW^{EB/M} >SW^{RTM/M} \).

Appendix 4: The Model with Output-Commitment

In the main text, we have analysed a model in which the firm’s announcement of its planned level of output has no effect on consumer expectations. This is because consumers have been assumed to make their purchase decisions before the actual size of the network is known. In other words, consumers form their expectations about the size of the network with which each firm is associated. It has also been assumed that, in equilibrium, consumers’ expectations are fulfilled. As Katz and Shapiro (1985, Appendix A) remarks, and Amir and Lazzati (2011) considers when modeling Cournot oligopoly, the model presented can be viewed as one in which the firms are not able to commit themselves. Their basic argument is an empirical one according to which in some contexts firms may be able to commit strongly to an output level; therefore, only the equilibrium output levels are credible announcements. However, it may be alternatively assumed that firms can commit to their announced output levels before consumers make their purchase decisions. If firm i may credibly commit itself to a certain output level, firm i can directly influence the consumers’ expectations about the size of its network. As a consequence, the firm i’s reaction curve shifts upwards with respect to the earlier equilibrium reaction correspondence. The latter shift in turn leads to a standard Cournot equilibrium with demand-side economies of scale.

Thus, the monopoly inverse demand function in Eq. (2) becomes

and, in duopoly, Eq. (6) modifies inFootnote 15

After the solution of the standard maximisation problems, we obtain the following equilibrium profits

These results correspond to those of Fanti and Buccella (2015), with the profit outcomes scaled simply up by the factor \(\frac{1}{1-n}\) while keeping the payoff rankings unchanged. The rationale for this result is most probably due to a less pronounced impact of the network effect on the relevant variables because each firm, loosely speaking, internalises the part of the consumption externalities due to the own output level. Therefore, the qualitative findings of Fanti and Buccella (2015) under committed bargaining with threat of entry and firms choosing the agenda are here confirmed: the EB and SEB agenda can strategically be used to deter market entry. With respect to the model presented in the main text, also the model with output commitment validates that the EB and SEB agendas have potential entry deterrence effect. However, the incumbent loses the possibility of using the RTM agenda to block entry when the network effects become sufficiently high for enlarging ranges of the union bargaining power. Moreover, sufficiently high network effects are no longer able to eliminate the existing barrier (e.g., EB or SEB).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fanti, L., Buccella, D. Bargaining Agenda and Entry in a Unionised Model with Network Effects. Ital Econ J 2, 91–121 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-015-0026-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-015-0026-3