Abstract

Non-isothermal oxidation of brown coal with 5 wt% of Cu(NO3)2, 5 wt% of Ce(NO3)3 and {2.5 wt% Cu(NO3)2 + 2.5 wt% Ce(NO3)3} additives was studied. The introduction of additives was carried out by an incipient wet impregnation method to ensure uniform distribution of cerium and copper nitrates within the structure of coal powdery samples (according to SEM and EDX mapping). The samples reactivity was studied in an isothermal oxidation regime at 200 °C (1 h) and by DSC/TGA at 2.5 °C/min heating rate. The additives implementation was found to reduce significantly the oxidation onset temperature (ΔTi = 20–55 °C), the samples oxidation delay time (Δti = 2–22 min) and overall duration of the oxidation process (Δtc = 8–16 min). The additives efficiency could be graded in accordance with the activation on the coal oxidation in the following row: Cu(NO3)2 > {Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3} > Ce(NO3)3. According to the mass spectroscopy, the obtained row of activation correlates well with the initial temperature of the studied nitrate’s decomposition (from 190 to 223 °C). A presence of nitrates was found to change significantly the trend of heat release taking place during the oxidation of coal samples (according to DSC/TGA data). The influence of coal morphology and volatiles content in initial sample on the parameters of the oxidation process was studied as well. Activation energy (Ea) of the coal oxidation was calculated using Coats–Redfern method. Maximum decrease in Ea from 69 to 58 kJ/mol was observed for the samples with Cu(NO3)2.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A coal is one of the most popular types of fuel for heat and electricity production along with natural gas and oil (International Energy Agency 2017). The explored coal reserves will last approximately 120 years while for oil and natural gas this period is at least twice shorter according to the reports of British Petroleum (2017). Data on explored coal resources significantly affect the market value of energy carriers (British Petroleum 2017). Nowadays, the cost of heat produced by coal burning is still approximately 2.6 times lower compared to natural gas, and this value is the lowest in the history. Thus, a coal is still being one of the most attractive energy carriers from an economic point of view. However, the wide use of coal is limited by a number of problems like the rate of combustion process, the incompleteness of combustion and the formation of toxic gases in furnaces (CO, NOx, SO2) (Kontorovich et al. 2014; Freese et al. 2008).

The simplest and the most effective way of using coal in the energy sector is its direct burning. According to Chang et al. (2016), current studies in this area are dedicated to a search for new technologies aimed to increase the efficiency of combustion, reduce capital costs for new equipment and improve its environmental performance. One of such approaches is focused on intensification of the coal combustion process by using of activation additives in order to improve the efficiency of coal combustion (Tikhov et al. 2013). Existing experience in the activation additives for solid fuel combustion is based on using the alkaline-earth oxides (MgO, CaO) and transition metals oxides (MnO2, CuO) (Li et al. 2007; Gong et al. 2009, 2010a, b; Wei et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2013), different salts (MgCl2, Ni(NO3)2, LiCl) and alkalis (NaOH, KOH) (Zhao et al. 2011; Abbasi-Atibeh and Yozgatligil 2014; Guo et al. 2014; Yin et al. 2012; He et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2012; Fangxian et al. 2009).

A number of researchers have proven that the using of alkaline and alkaline-earth metals as combustion activators results in the acceleration of volatiles release along with the decrease in ignition temperature of the coals (Hedden and Wilhelm 1980; Altun et al. 2001; Matsuzawa et al. 2007). Intensification of carbon matrix thermal decomposition followed by oxidation of condensed products is observed in the presence of additives (Rustamov et al. 1998). However, application of alkaline and alkaline-earth metals in the energy sector is limited by their high corrosive activity and slag formation (Gong et al. 2010a).

Oxides of rare-earth and transition metals are also known to increase the efficiency of coal combustion (Ganduglia-Pirovano et al. 2007; Aho et al. 1990, 1991). The influence of CeO2, Fe2O3 and double-based Fe2O3/K2CO3 additives on the combustion kinetic characteristics of coal with different morphology is reported in Gong et al. (2010a). The double-based Fe2O3/K2CO3 additive had a positive effect on thermal destruction and combustion of various solid fuels. The degree of additive influence strongly depends on the carbon content in initial coal and tends to increase with degree of metamorphism (Zhang et al. 1997). The most significant changes in the kinetics of coal combustion in a presence of metal oxides are reported to appear within the high-temperature zone (above 550 °C) (Liu et al. 2002).

Many nitrates are known to have strong oxidizing properties, low melting (decomposition) point and excellent solubility in water (Morozov et al. 2003). The latter significantly simplifies their application using the incipient wetness impregnation of the solid fuel. For example, the use of Ni(NO3)2 as the activation additive has superior effect in decrease the coal ignition temperature (up to about 50 °C) in comparison with other metal oxide additives (Zhao et al. 2011). In addition, the metal nitrate decomposition leads to the formation of appropriate oxides which are capable to catalyze the further coal oxidation (Ryu et al. 2004).

The results of the study of oxidation of two types of coals modified with cerium nitrate and copper nitrate are presented in this paper. CuO and CeO2 oxides are known to perform high catalytic activity in coal oxidation processes (Sheng et al. 2017).

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and their characterization

Coals of Borodinsky (sample #1) and Balakhtinsky (sample #2) deposits of the Kansk-Achinsk coal basin were used in the study. The raw samples with particle size of 5–10 mm were grinded in a ball mill (Pulverizette, Germany) using the following parameters: the balls (ZrO2, 10 mm in diameter) to material mass ratio was 1:1; the duration of the procedure was 1 h. Finally, the samples were sorted by sieving to obtain the particles with the size less than 80 μm.

The particle size distribution of the coal powders were measured using the Analysette 22 laser particle diffraction analyzer (Fritsch, Germany).

The sieved coal powders were dried at 105 °C until reaching a constant weight. Structure and morphology of the coal samples and its mineral residues were studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a JSM-6460LV microscope (JEOL, Japan) with ionic focused beam. Volume and average pore size were determined by the low-temperature nitrogen adsorption method (BET) using an automatic gas adsorption analyzer 3Flex (Micromeritics, USA).

2.2 Introduction of additives by impregnation method

Crystalline hydrates of transition metal nitrates (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O and Cu(NO3)2·3H2O) were taken as additives by oxidation. The main characteristics (Larionov et al. 2016; Miroshnichenko and Balaeva 2013; Phokha et al. 2012; Wayne 2005) of the samples used are shown in Table 1.

The incipient wetness impregnation method was chosen for the introduction of additives (Tokareva et al. 2015). The 50 vol% C2H5OH in H2O solution was used as an impregnator to overcome the hydrophobic properties of powdery coal. The moisture capacitance of the dried coal samples (in mL/g) was determined prior to the impregnation procedure.

Impregnated samples were dried at 105 °C for 20 h in air. The additives concentration in all samples (in relation to dry salt) was 5 wt%. For the comparative analysis, reference samples without additives were prepared using the same treatment procedures.

The list of the prepared samples and their symbols are given in Table 2.

To study the effect of cerium oxide and copper oxide on the coal oxidation process the impregnated coal samples were heated in air at 200 °C for 1 h to convert cerium and copper nitrates into their corresponding oxides (see also reaction 1).

2.3 TGA and MS analysis

The oxidation of modified coal samples was studied using the thermal analyzer STA 449 C Jupiter (Netzsch, Germany). All experiments were carried out with the heating rate of 2.5 °C/min in corundum crucible with perforated cover in a temperature range of 45–600 °C. When the sample (~ 7 mg) was loaded into the analyzer an air (60 mL/min) was passed through the system. All experiments were carried out under atmospheric pressure.

A qualitative analysis of the composition of gaseous oxidation products by DSC/TGA was performed. The analysis was carried out using a QMS 403 D Aëolos interfacing quadruple mass spectrometer (Netzsch, Germany).

2.4 Reactivity parameters

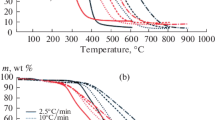

A comparative evaluation of coal reactivity during oxidation was carried out using the following parameters: temperature, time and oxidation rate, which were calculated by the graphical method (Zou et al. 2016) using TG and DTG curves (Fig. 1).

Points A and B on the TG curve were defined by tangential method (Yin et al. 2012) and they characterize the temperatures of the oxidation onset (initial temperature, Ti) and oxidation end (final temperature, Tf). Point C represents extremum on DTG curve corresponding to the maximum value of the mass loss rate (Wmax) at the certain temperature (Tmax). The following parameters were determined using points A and B as shown in Fig. 1: te (time of sample heating before intense oxidation) and tf (time of full oxidation).

Activation energy (Ea) of the oxidation process was defined using the Coats–Redfern method (Kok 2002; Xie and He 1998; Santos et al. 2007; Coats and Redfern 1964). This method is based on the Eq. (1).

where α is coal conversion, from 0 to 1; T is the temperature, K; R is the universal gas constant, J/(mol K); A is the pre-exponential factor, 1/min; Ea is the activation energy, J/mol; β is the heating rate, K/min.

The solution of Eq. (1) and the definition of the basic reactivity parameters were performed using TG analysis results by plotting the dependence ln(− ln(1 − α)/T2) versus 1/T. The obtained dependence was analyzed in conversion degree α range from 0.1 to 0.9 and approximated by linear dependence in accordance with the Eq. (2).

The values of activation energy Ea [Eq. (1)] were calculated from the slope of the line (coefficient C2). The chosen range of the conversion is explained by the fact that values of α < 0.1 and α > 0.9 usually leads to a nonlinear dependence due to the increasing measurement errors (Vyazovkin et al. 2011).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of the initial and modified samples

Main characteristics of the initial coal samples that were grinded and dried at 105 °C are given in Table 3. The high content of volatiles (35%–40 wt%) and the relatively small ash content (less than 5 wt%) are typical for brown coal. The pretreated under the same grinding conditions samples have similar particle size distribution (X50 = 20–21 µm). Despite the low porosity of samples (less than 0.03 cm3/g), this material is characterized by low moisture capacity (Table 3) and, thus, it is easy to apply soluble nitrate on coal particles with one-step impregnation.

The elemental analysis results of studied coal mineral residue are presented in Table 4. In general, samples are characterized by the similar elemental composition with a high Ca content. The significant content of copper oxide (< 1 wt%) was also observed for sample #2-ref.

SEM images of the non-impregnated initial coal samples are shown on Fig. 2. Samples of the investigated coals consist of irregularly shaped faceted particles with an inhomogeneous surface containing many small fragments with a size of less than 5 μm. The character of the cerium and copper nitrates distribution within the structure of coal for the samples of the #1 series was studied using EDX mapping. SEM/EDX images for modified samples #1-Ce, #1-Cu and #1-Ce + Cu as well as the corresponding ash residues obtained after oxidations up to 600 °C are shown in Fig. 3.

The results of the analysis revealed that both the individual and joint introduction of cerium and copper nitrates by the impregnation method provides a fairly uniform distribution of the additives on the surface of coal particles. It should be also mentioned that after oxidation the distribution of cerium and/or copper in the mineral residue structure remains uniform (Fig. 3). The size of the residual ash particles is much smaller compared to the initial coal particles (Fig. 3).

As the next step, all prepared samples were placed in a lab furnace and kept at 200 °C in air for 1 h. The choice of temperature was motivated by the fact that at given temperature both cerium and copper nitrates are unstable and undergo decomposition with formation of corresponding oxides. The weighting of samples after treatment showed that in the presence of nitrates a sharp acceleration of coal oxidation process takes place. It causes a significant weight loss (from 7% to 20 wt%) compared to unmodified initial samples (1%–2 wt%). These results are presented on Fig. 4.

The weight loss of the modified samples is related to the removal of moisture, the decomposition of the deposited metal nitrates and the partial release of volatile substances as a result of the oxidation onset by the decomposition of nitrates. This result allows to determine the following row of reactivity for the used additives: Cu(NO3)2 > {Ce(NO3)3 + Cu(NO3)2} > Ce(NO3)3. Thus, the effect of mutual activity enhancement (synergism) with simultaneous using of cerium and copper nitrates in this case was not observed (the effect appears to be additive). Higher reactivity of copper nitrate can be explained by lower temperature of Cu(NO3)2 decomposition compared with cerium nitrate (Table 1).

It should also be noted that the highest weight change during the calcination was observed in case of the modified coal samples of series #2. The difference between the series of modified samples #1 and #2 is considered to appear due to different carbon and volatile compounds content in the initial samples (Table 3) which correlates well with the literature (Gong et al. 2010b; Yin et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 1997).

Impact of metal oxides formed under heating up to 200 °C on the coal oxidation is severe probably because of its earlier onset. Most likely, an intensification of coal oxidation process was caused by the nitrate decomposition step. However, it is still unclear what was the key property of the coal that was responsible for its oxidation, accelerated by copper and cerium nitrates.

3.2 Effect of additives on coal oxidation characteristics

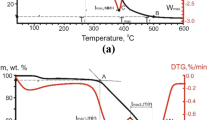

Results of the investigation of coal oxidation by TGA/DTG are given on Fig. 5. It was found that in all cases the introduction of additive has an activation influence: oxidation onset temperature of modified coals (Ti) was reduced.

Comparison of obtained results (Fig. 5a, b) reveals that the initial samples of coal (#1-ref and #2-ref) have similar character of decomposition and close values of oxidation onset temperatures (Ti): 260 and 280 °C, respectively. Parameter Tf (time of complete oxidation, see Fig. 1) for compared samples was different: 500 °C (#1-ref) and 520 °C (#2-ref). Different Ti and Tf values were resulted from the differences in the volatile matter and carbon content in the composition of the initial samples #1 and #2 (Table 3). On the other hand, the rate of volatile substances release is strongly dependent on the coal particle morphology. Thus, coal with non-uniform structure and large internal pores (Fig. 2, Table 3) is exposed to a more intense influence of the internal thermal degradation. It accelerates the release of volatiles (Senneca et al. 2017).

Analysis of DTG profile (Fig. 5c, d) allows distinguishing four steps of sample weight loss:

-

(1)

removal of moisture (25–100 °C);

-

(2)

thermal degradation of the particles with the release of volatile matter (100–260 °C);

-

(3)

oxidation of the volatile compounds after release (260–360 °C);

-

(4)

after-oxidation of carbon residue (360–520 °C).

As it is seen from Fig. 5, the weight loss of samples for the first stage of the process was less than 2 wt%, which can be explained by using the pre-dried samples in experiments. As it was mentioned above, the decomposition of brown coal takes place on the step 2 resulting in oxidation of volatiles (step 3). The oxidation is accompanied by further volumetric destruction of particles. It promotes the release of volatile compounds from the particle’s volume. Thus, the significant change in structure of the reacting part of the fuel with the expansion of internal cracks and pores (Li et al. 2015) which intensify interaction between the surface and an oxidizing medium (Deng et al. 2017) is, probably, the result of the steps 1–3.

It is worth mentioning that it is impossible to distinguish the transition between the steps 3 and 5 using DTG curves of the modified coal samples, since the oxidation of the resulting coke is parallel with after-oxidation of released volatiles (Fig. 5).

In the case of modified coal samples (Fig. 5), the active weight loss was observed in the temperature range 190–210 °C. It is associated with the decomposition of the deposited metal nitrates (Table 1). Nitrates decomposition on the surface of coal particles promotes significant shift of the oxidation onset temperature towards the low temperature region. The most significant difference in the value of parameter Ti was observed for the samples containing 5 wt% Cu(NO3)2, while the minimum one was found for Ce(NO3)2. Complex additive {Ce(NO3)3 + Cu(NO3)2} had an intermediate activity. The effect of additives on parameter ΔTi (oxidation onset temperature difference) for both types of coals is presented on Fig. 6.

The highest values of ΔTi (40 °C and 55 °C) were observed for coal samples modified by copper nitrate (#1-Cu and #2-Cu, respectively). Thus, thermogravimetric analysis data were completely consistent with results which were obtained during the isothermal oxidation of samples in air (Fig. 4).

It should be noted that this result is also in agreement with previously published data (Gong et al. 2009), where the positive effect of additive was proved to be enhanced with increasing the carbon content in sample. The molecular structure of brown coal is characterized by array of lateral and bridging bonds prone to fracture at sufficiently low temperatures. It is especially important for the active oxygen-containing functional groups: –OCH2, –OH, –COOH, –C=O (Zhang et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016). With the surface increasing, the concentration of functional groups decreases and additives affect the oxidation during heating.

Further development of the oxidation process has a similar character for both sample series. Moreover, for all modified samples at the early stages of the reaction an increase of the reaction rate (Fig. 6) along with a reduction in the intensive oxidation temperature was observed. At the same time, for coal modified with Ce(NO3)3 the weight loss rate decreases with further increase in temperature, and the curves becomes similar to that for the initial samples. The opposite is valid for samples with Cu(NO3)2 and {Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3} additives. With increasing the temperature, the slope of the TG curve becomes steeper. It indicates the oxidation acceleration of the coals in the temperature range of 280–380 °C.

A similar effect of ΔTi on additive type (Fig. 6) was observed for the characteristic points of the DTG curves where the oxidation rate had its maximum value (Fig. 5c, d). The maximum change of the Tmax parameter (temperature corresponding to the maximum reaction rate) was 100 °C (Table 5). It should be mentioned that the introduction of additives results in noticeable change in the DTG curve shape in comparison with initial samples. Additives promote the oxidation of pyrolysis gas and carbon residue within the same stage.

Introduction of additives results in significant lowering of the oxidation onset temperature, increasing the oxidation rate during the step of volatiles release, and acceleration of the process during the step of coke residue after-oxidation.

It should be noted that the position of exothermic peaks in DSC curves (Fig. 5e, f) is nearly identical with the values for Tmax, which correspond to the maximum oxidation rate (calculated from the DTG data, Fig. 5c, d).

Exo-effects observed with DSC (Fig. 5e, f) were associated with exothermic heat release in the oxidation of the pyrolysis gas (volatile matter) and carbon residue steps (Ozbas et al. 2003). DSC curves for the initial samples #1-ref and #2-ref are characterized by bimodal form that allows one to distinguish individual process steps quite evidently. With an increase of additive activity, tendency to merge two separate stages of heat release into one becomes stronger. For example, for the samples #1-Ce and #2-Ce the first peak at 300 °C was transformed into a characteristic “shoulder”. At the same time, for the samples modified with the most active copper nitrate, DSC curves have a single maximum of heat release, which was moved towards the lower temperatures: \(\Delta T_{\hbox{max} 1}^{{\# 1 - {\text{Cu}}}} = 96\,{^\circ }{\text{C}}\) and \(\Delta T_{\hbox{max} 1}^{{\# 2 - {\text{Cu}}}} = 112\,{^\circ }{\text{C}}\). Probably, the decomposition of the metal nitrates occurs simultaneously with the oxidation of volatile compounds which release occurred from both the surface of coal particles and its inner parts.

3.3 MS analysis

The mass spectrometric (MS) profiles of primary gaseous products (CH4, CO2 and NOx) for the samples of series #1 are shown on Fig. 7. For better clarity, MS analysis data are presented together with DSC curves for the same samples.

Results of mass spectrometric analysis (temperatures corresponding to MS curve maximums Tmax, difference between modified and initial sample ΔTmax, extremum of the temperature corresponding to the decomposition of metal nitrates Tdec) are summarized in Table 5.

Methane was appeared in gas phase as a by-product of coal thermal decomposition. The temperature dependence of methane (m/z = 16) yield has the single peak around 360 °C, which is moved to the low temperature region in the case of the sample with additives (Fig. 7). The temperature shift value (ΔTmax) increases in a row: Cu(NO3)2 > {Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3} > Ce(NO3)3, which is in good agreement with the DSC analysis data (Table 5). It means that introduction of nitrates promotes thermal degradation while facilitating the release of the volatile compounds.

Carbon dioxide (m/z = 44) (main product of oxidation) release is characterized by a bimodal curve for the sample #1-ref. Shape of MS profile for CO2 looks like a mirror image of the corresponding DSC curve (Fig. 7). The first maximum (320 °C) is associated with the oxidation of desorbed volatiles. The second peak (380 °C) is connected to the oxidation of the coke residue. Introduction of promoting additives decreases volatiles release and oxidation onset temperatures. The highest temperature peak shift was observed for the sample #1-Cu (\(\Delta {\text{T}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}^{\text{Cu}} = 97\,{^\circ }{\text{C}}\)). For samples #1-Ce and #1-Ce + Cu, these values are \(\Delta {\text{T}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}^{\text{Ce}} = 42\,{^\circ }{\text{C}}\) and \(\Delta {\text{T}}_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} }}^{\text{Ce + Cu}} = 78\,{^\circ }{\text{C}}\), respectively (Table 5).

The lower graph on Fig. 7 compares the mass spectrometric data on nitrogen oxides NOx (m/z = 30) for various additives. It is seen that the introduction of cerium and/or copper nitrate results in a substantial changes of MS profile. The broad peak at low temperature area (190–223 °C) appeared for all modified samples. This is obviously caused by the thermal decay of nitrates (Fig. 7). Character of NOx release indicates that the decomposition of Cu(NO3)2 begins at about 130 °C. It allows one to assume the certain degree of participation of the carrier (coal) in the process (Ruiz et al. 2010). It should be noted that the decomposition of complex additive {Cu(NO3)2 + Ce(NO3)3} occurs within a broad peak at 135–270 °C (Fig. 7), indicating the uniform distribution of nitrates using the method of impregnation with joint solution.

The second, less intense wave of NOx release refers to the formation of nitrogen oxides (Fig. 7). Thus, a shift of the second peak to lower temperatures (410 °C → 340 °C) took place. Its magnitude was in dependence on the type of the additive (Table 5). It is important that this process was accompanied by a significant decrease in the NOx formation rate as it seen from the comparison of the data in Fig. 7.

Nitrogen oxides, which are formed by the decomposition of the nitrates, were, probably, the reason of coal oxidation acceleration (Shao et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2015a, b). Nitrogen oxides, thus, were responsible for the early release of volatile compounds and their subsequent intensive oxidation. Comparing the DTG and MS analysis data (Fig. 7), we concluded that oxidation onset temperature shift \(\Delta T_{\text{i}}\) correlates directly with the temperature of corresponding nitrates decomposition.

3.4 Reactivity parameters of oxidation

TGA data analysis allowed one to calculate and compare the characteristics of modified brown coal oxidation with additives. Results of the calculation are presented in Table 6.

As it was already noted, the maximal accelerating effect is realized in the case of using copper nitrate as an additive for both series of the samples. The observed effect was in reducing the oxidation onset temperature Ti by 40–55 °C, shifting maximal oxidation rate temperature by 100 °C, and reducing the total sample oxidation time by 8–16 min (Table 6). With Ti values decreasing, the duration of heating steps (steps 1 and 2) and the direct oxidation steps (steps 3 and 5) was also decreased. It should also be noted that in presence of promoting additive, a substantial decrease in the maximal sample weight loss rate (up to 1.5 times) is observed as a result of oxidation (Table 6).

The graphs plotted from the TGA data in coordinates \(\ln\left[ { - \frac{{\ln\left( {1 -\upalpha} \right)}}{T^{2}}} \right]\) versus 1/T according to the Coats–Redfern method (Xie and He 1998) are given on Fig. 8. The values of activation energy (Ea) are given in Table 6 (bottom row) calculated from the slope of these lines. The initial samples #1-ref and #2-ref have the same values of the activation energy: 69 kJ/mol. These values are in good agreement with a literature (Fangxian et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2015c). Introduction of additives causes a decrease in Ea in all the cases.

Linearly approximated dependence \(\ln \left[ { - \frac{{\ln \left( {1 -\upalpha} \right)}}{T^{2}}} \right]\) versus 1/T calculated using the TGA data via Coats–Redfern method. See Table 2 for samples’ symbols

The maximal decrease in activation energy (ΔEa ~ 11 kJ/mol), as expected, was observed for the most active copper nitrate (Table 6).

Considering the possible mechanism of initiating additive action (for example, Cu(NO3)2) during coal oxidation, a following set of parallel reactions exist:

At the first, heating of copper nitrate (up to 170 °C and above) promotes its degradation according to Eq. (3). At the same time, according to MS analysis data, decomposition of Cu(NO3)2 salt begins at lower temperatures (near 130 °C). It indicates that the carbon acts as a reducer [Eq. (4)] during oxidation. Nitrogen oxides NO and NO2 are formed by the nitrate decomposition. The NO2 in this case acts as a strong oxidizing agent promoting combustion of carbon and volatile compounds [Eqs. (5) and (6)]. Coal interaction with nitrogen dioxide is followed by NO formation, which is oxidized by atmospheric oxygen according to reversible reaction [Eq. (7)].

After complete decomposition of Cu(NO3)2 the disperse nonstoichiometric copper oxide CuOx is formed. This oxide is uniformly distributed in the structure of the sample (according to the EDA-mapping, Fig. 3). Copper oxide is known to possess high catalytic activity towards complete oxidation of organic substrates and fuel (Li et al. 2007). Thereby, it may accelerate brown coal oxidation according to Eq. (8).

4 Conclusions

The effect of cerium and copper nitrates additives on the brown coal non-isothermal oxidation was studied. Introduction of the additives via incipient wet impregnation was ensured the uniform distribution of the nitrates over the structure of coal samples. Heating of coal samples in air under isothermal conditions (200 °C, 1 h) revealed that the decomposition of introduced nitrate was accompanied by the activation of the brown coal thermal degradation and oxidation (weight loss from 8% to 20 wt%). Further investigations of coal sample oxidation by TGA allowed to determine the following row of studied nitrates reactivity:

Analysis of the oxidation characteristics has shown that the application of nitrates additives reduces the oxidation onset temperature Ti by 20–55 °C and decreases the total sample oxidation time tf. Maximal reduction of oxidation duration (Δtf = 16 min) was obtained for the sample #1-Cu, which corresponds to an increase in oxidation efficiency by 17%.

Calculations of activation energy of oxidation brought us to conclusion that the use of metal nitrates as additives reduces the kinetic barrier of thermal degradation and oxidation reactions for coal. That leads to a significant acceleration of the overall oxidation process and the whole process shifted towards low temperature region. Significant role in accelerating of oxidation process may also be attributed to the catalytically active metal oxides, which were resulted from decomposition of the corresponding nitrates.

Obtained results of brown coal oxidation in presence of copper and cerium nitrates may be further applied for the development of novel energy efficient technologies for coal oxidation (Slyusarskiy et al. 2017).

References

Abbasi-Atibeh E, Yozgatligil A (2014) A study on the effects of catalysts on pyrolysis and combustion characteristics of Turkish lignite in oxy-fuel conditions. Fuel 115:841–849

Aho MJ, Tummavuori JL, Hämäläinen JP (1990) Importance of iron and aluminium in rapid and slow combustion of peat. Fuel 69:639–642

Aho MJ, Hämäläinen JP, Tummavuori JL (1991) Catalytic effects of metals on peat combustion. Fuel 70:1143–1145

Altun NE, Hicyilmaz C, Kok MV (2001) Effect of different binders on the combustion properties of lignite—Part I. Effect on thermal properties. J Therm Anal Calorim 65(2):787–795

British Petroleum (2017) Statistical review of world energy 2015. London. http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy/coal. Accessed 20 Feb 2018

Chang SY, Zhuo JK, Meng S, Qin SY, Yao Q (2016) Clean coal technologies in China: current status and future perspectives. Engineering 2(4):447–459

Coats AW, Redfern JP (1964) Kinetic parameters from thermogravimetric date. Nature 201:68–69

Deng J, Li Q, Xiao Y, Wen H (2017) The effect of oxygen concentration on the non-isothermal combustion of coal. Thermochim Acta 653:106–115

Fangxian L, Shizong L, Youzhi C (2009) Thermal analysis study of the effect of coal burning additives on the combustion of coals. J Therm Anal Calorim 95:633–638

Freese B, Clemmer S, Nogee A (2008) Coal power in a warming world. UCS Publications, Cambridge

Ganduglia-Pirovano MV, Hofmann A, Sauer J (2007) Oxygen vacancies in transition metal and rare earth oxides: current state of understanding and remaining challenges. Surf Sci Rep 62(6):219–270

Gong X, Guo X, Wang Z (2009) Variation of char structure during anthracite pyrolysis catalyzed by Fe2O3 and its influence on char combustion reactivity. Energy Fuels 23:4547–4552

Gong X, Guo Z, Wang Z (2010a) Reactivity of pulverized coals during combustion catalyzed by CeO2 and Fe2O3. Combust Flame 157:351–356

Gong X, Guo Z, Wang Z (2010b) Variation on anthracite combustion efficiency with CeO2 and Fe2O3 addition by differential thermal analysis (DTA). Energy 35:506–511

Guo Q, Liu Y, Jia W, Yang M, Hu X, Ryu HJ (2014) Performance of Ca-based oxygen carriers decorated by K2CO3 or Fe2O3 for coal chemical looping combustion. Energy Fuels 28:7053–7060

He XM, Qin J, Liu RZ, Hu ZJ, Wang JG, Huang CJ, Li TL, Wang SJ (2013) Catalytic combustion of inferior coal in the cement industry by thermogravimetric analysis. Energy Source Part A 35:1233–1240

Hedden K, Wilhelm A (1980) Catalytic effects of in organic substances on reactivity and ignition temperature of solid fuels. Ger Chem Eng 3(2):142–147

Huang CJ, Wang SJ, Wu F, Zhu P, Zhou ZH, Yi JM (2013) The effect of waste slag of the steel industry on pulverized coal combustion. Energy Source Part A 35:1891–1897

International Energy Agency (2017) Coal information. http://www.iea.org/Sankey. Accessed 20 Feb 2018

Kim YK, Hao LF, Park JI, Miyawaki J, Mochida I, Yoon SH (2012) Catalytic activity and activation mechanism of potassium carbonate supported on perovskite oxide for coal char combustion. Fuel 94:516–522

Kok MV (2002) An investigation into the thermal behavior of coals. Energy Sour 24:899–906

Kontorovich AE, Epov MI, Eder LV (2014) Long-term and medium-term scenarios and factors in world energy perspectives for the 21st century. Russ Geol Geophys 55:534–543

Larionov KB, Zenkov AV, Yankovsky SA, Ditc AA (2016) Change of coal-water fuel rheological properties by rotary flows modulation. IFOST 7884323:568–571

Li XG, Ma BG, Xu L, Luo ZT, Wang K (2007) Catalytic effect of metallic oxides on combustion behavior of high ash coal. Energy Fuel 21:2669–2672

Li Z, Liu D, Cai Y, Yao Y, Wang H (2015) Pore structure and compressibility of coal matrix with elevated temperatures by mercury intrusion porosimetry. Energ Explor Exploit 33:809–826

Liu Y, Che D, Xu T (2002) Catalytic reduction of SO2 during combustion of typical Chinese coals. Fuel Process Technol 79:157–169

Liu J, Luo L, Ma J, Zhang H, Jiang X (2016) Chemical properties of superfine pulverized coal particles. 3. nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of carbon structural features. Energy Fuels 30:6321–6329

Matsuzawa Y, Mae K, Hasegawa I, Suzuki K, Fujiyoshi H, Ito M, Ayabe M (2007) Characterization of carbonized municipal waste as substitute for coal fuel. Fuel 86(1–2):264–272

Miroshnichenko DV, Balaeva YS (2013) Calculating the higher heat of coal combustion in the wet ash-free state. Coke Chem 56:85–89

Morozov IV, Znamenkov KO, Korenev YM, Shlyakhtin OA (2003) Thermal decomposition of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O at reduced pressures. Thermochim Acta 403:173–179

Ozbas KE, Kök MV, Hicyilmaz C (2003) DSC study of the combustion properties of turkish coals. J Therm Anal Calorim 71(3):849–856

Phokha S, Pinitsoontorn S, Chirawatkul P, Poo-arporn Y, Maensiri S (2012) Synthesis, characterization, and magnetic properties of monodisperse CeO2 nanospheres prepared by PVP-assisted hydrothermal method. Nanoscale Res Lett 7:1–13

Ruiz ML, Lick ID, Ponzi MI, Castellón ER, Jiménez-López A, Ponzi EN (2010) Thermal decomposition of supported lithium nitrate catalysts. Thermochim Acta 499(1–2):21–26

Rustamov VR, Abdullayev KM, Samedov EA (1998) Biomass conversion to liquid fuel by two-stage thermochemical cycle. Energy Convers Manag 39(9):869–875

Ryu SK, Lee WK, Park SJ (2004) Thermal decomposition of hydrated copper nitrate [Cu(NO3)2·3H2O] on activated carbon fibers. Carbon Sci 5(4):180–185

Santos JCO, Oliveria AD, Silva CC, Silva JDS, Souza AG, Lima LN (2007) Kinetic and activation thermodynamic parameters on thermal decomposition of synthetic lubricant oils. J Therm Anal Calorim 87:823–829

Senneca O, Scala F, Chirone R, Salatino P (2017) Relevance of structure, fragmentation and reactivity of coal to combustion and oxy-combustion. Fuel 201:65–80

Shao W, Wang Z, Zhang X, Wang L, Ma Z, Li Q, Zhang Z (2016) Promotion effects of cesium on perovskite oxides for catalytic soot combustion. Catal Lett 146:1397–1407

Sheng J, Li C, Zhao L, Du X, Gao L, Zeng G (2017) Efficient removal of HCHO from simulated coal combustion flue gas using CuO–CeO2 supported on cylindrical activated coke. Fuel 197:397–406

Slyusarskiy K, Larionov K, Osipov V, Jankovsky S, Gubin V, Gromov A (2017) Non-isothermal kinetic study of bituminous coal and lignite conversion in air and in argon/air mixtures. Fuel 191:383–392

Tikhov SF, Simonov AD, Yazykov NA, Dubinin YV, Yakovlev VA, Sadykov VA, Salanov AN, Suprun EA, Parmon VN (2013) Catalytic combustion of brown coal particulates over ceramometal honeycomb catalyst. Catal Sustain Energy 1:82–89

Tokareva IV, Mishakov IV, Korneev DV, Vedyagin AA, Golokhvast KS (2015) Nanostructuring of the carbon macrofiber surface. Nanotechnol Russ 10:158–167

Vyazovkin S, Burnham AK, Criado JM, Pérez-Maqueda LA, Popescu C, Sbirrazzuoli N (2011) ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim Acta 520:1–19

Wang Y, Wang J, Chen H, Yao M, Li Y (2015a) Preparation and NOx-assisted soot oxidation activity of a CuO–CeO2 mixed oxide catalyst. Chem Eng Sci 135:294–300

Wang Z, Lu P, Zhang X, Wang L, Li Q, Zhang Z (2015b) NOx storage and soot combustion over well-dispersed mesoporous mixed oxides via hydrotalcite-like precursors. RSC Adv 5:52743–52753

Wang H, Li C, Peng Z, Zhang S (2015c) Kinetics of the catalytic combustion of coal tar. Energy Source Part A 37:2323–2329

Wang DM, Xin HH, Qi XY, Dou GL, Qi GS, Ma LY (2016) Reaction pathway of coal oxidation at low temperatures: a model of cyclic chain reactions and kinetic characteristics. Combust Flame 163:447–460

Wayne HR (2005) Copper compounds. Ullmann’s encyclopedia of industrial chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim

Wei L, Zhang N, Yang T (2012) Effects of alkaline earth metal on combustion of pulverized coal. Adv Mater Res 516–517:271–275

Xie JL, He F (1998) Catalytic combustion study of Anthracite in cement kiln. J Chin Ceram Soc 26:792–795

Yin K, Zhou YM, Yao QZ, Fang C, Zhang ZW (2012) Thermogravimetric analysis of the catalytic effect of metallic compounds on the combustion behaviors of coals. React Kinet Catal Lett 106:369–377

Zhang LM, Tan ZC, Wang SD, Wu DY (1997) Combustion calorimetric and thermogravimetric studies of graphite and coals doped with a coal-burning additive. Thermochim Acta 299:13–17

Zhang L, Hu S, Chen Q, Xiao L, Shatir A, Syed-Hassan SSA, Jiang L, Wang Y, Su S, Xiang J (2017) Molecular structure characterization of the tetrahydrofuran-microwave-extracted portions from three Chinese low-rank coals. Fuel 189:178–185

Zhao GW, Yu WQ, Xiao YH (2011) Study on brown coal pyrolysis and catalytic pyrolysis. Adv Mater Res 236–238:660–663

Zou C, Zhao J, Li X, Shi R (2016) Effects of catalysts on combustion reactivity of anthracite and coal char with low combustibility at low/high heating rate. J Therm Anal Calorim 126:1469–1480

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Ministry of Education of Russian Federation within the framework of the project No. 13.7644.2017/8.9. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation in the framework of Increase Competitiveness Program of Tomsk Polytechnic University and NUST “MISIS”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Larionov, K.B., Gromov, A.A. Non-isothermal oxidation of coal with Ce(NO3)3 and Cu(NO3)2 additives. Int J Coal Sci Technol 6, 37–50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0229-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-018-0229-y