Abstract

The heterogeneity of unconventional reservoir rock tremendously affects its hydrofracturing behavior. A visual representation and accurate characterization of the three-dimensional (3D) growth and distribution of hydrofracturing cracks within heterogeneous rocks is of particular use to the design and implementation of hydrofracturing stimulation of unconventional reservoirs. However, because of the difficulties involved in visually representing and quantitatively characterizing a 3D hydrofracturing crack-network, this issue remains a challenge. In this paper, a novel method is proposed for physically visualizing and quantitatively characterizing the 3D hydrofracturing crack-network distributed through a heterogeneous structure based on a natural glutenite sample. This method incorporates X-ray microfocus computed tomography (μCT), 3D printing models and hydrofracturing triaxial tests to represent visually the heterogeneous structure, and the 3D crack growth and distribution within a transparent rock model during hydrofracturing. The coupled effects of material heterogeneity and confining geostress on the 3D crack initiation and propagation were analyzed. The results indicate that the breakdown pressure of a heterogeneous rock model is significantly affected by material heterogeneity and confining geostress. The measured breakdown pressures of heterogeneous models are apparently different from those predicted by traditional theories. This study helps to elucidate the quantitative visualization and characterization of the mechanism and influencing factors that determine the hydrofracturing crack initiation and propagation in heterogeneous reservoir rocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Hydrofracturing is the primary method of hydrocarbon reservoir stimulation that enhances unconventional gas recovery. Unconventional natural gas reservoirs usually are composed of different minerals and have a composite or heterogeneous microstructure (Fouche et al. 2004; He et al. 2015). As a result, the initiation and propagation of hydrofracturing cracks are usually influenced by the contrast between Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio of different components (Garcia et al. 2013; Sarmadivaleh and Rasouli 2015; Stanchits et al. 2014). Understanding the initiation and propagation of hydraulically induced cracks is key to predicting and measuring hydrofracturing behavior of low-permeability reservoirs.

Numerical models have been developed over recent decades to investigate the crack behavior in rock media. However, due to the heterogeneity of unconventional reservoirs, classical fracture models do not accurately predict the fracture pattern in these rocks. In recent years, different techniques have been used to incorporate heterogeneity into numerical models, such as FEM (Wang 2013), RFPA (Tang et al. 2002; Yang et al. 2004; Li et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2013), and PFC (Al-Busaidi et al. 2005; Hiyama et al. 2013; Shimizu et al. 2011, 2014) methods. In addition, there are other methods, such as unconventional fracture models (UFM) (Kresse et al. 2011, 2013), BEM (Zhang et al. 2007), XFEM (Wang et al. 2015), DDM (Gu et al. 2008). These numerical studies are useful for understanding and characterizing the initiation and propagation of hydrofracturing cracks. However, these numerical models are generally applied to simple media and become extremely complicated when random discontinuities or material heterogeneities are involved. Thus, the effectiveness of these models usually needs to be verified. This requires studying actual hydrofracturing crack patterns in the field or laboratory. However, it is challenging to observe these patterns in the rock media. In general, the acoustic emission method is widely used to monitor hydrofracturing crack patterns (Cipolla et al. 2008; Maxwell and Cipolla 2011; Maxwell et al. 2013; van der Baan et al. 2013; Warpinski 2014; Maxwell et al. 2015). However, uncertainties in the microseismic data, limitations of azimuthal coverage, and shortcomings of velocity models make it difficult to determine complex fracturing processes (Castano et al. 2010; Cipolla et al. 2012; Johnston and Shrallow 2011). In addition, the CT identification method has been employed to characterize fracture geometry in traditional hydrofracturing experiments carried out on rock or cement samples (Renard et al. 2009; Guo et al. 2014; Hampton et al. 2014; Zou et al. 2016). This method depends on the resolution and capabilities of the CT system. As a result, the size of the sample is usually limited and microfractures are difficult to identify. Therefore, a visual representation of the geometry of hydrofracturing cracks is of particular use to understanding the hydraulic fracturing pattern. Usually, Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), glass, and resin are widely used because of cost effectiveness and ease of processing. Wu et al. (2004) investigated hydrofracturing crack propagation in a layered formation which was composed of rigid and soft layers, and drew a map of fracture behavior in the vicinity of an interface. Wu (2006) revealed mixed mode fracturing by applying mode III loading to the cylindrical PMMA samples with a circle internal fracture. Wu et al. (2008) carried out a series of hydraulic fracturing test to observe fracture initiation and propagation in well orientations based on transparent PMMA samples. It was observed that far-field stresses had little influence on fracture initiation, but these stresses did influence the final fracture orientation. Kaswiyanto et al. (2014) used resin specimens to validate fracture mechanisms in the laboratory. Bunger et al. (2013) utilized both glass and PMMA samples to verify the efficiency of a numerical model by observing the crack path, and the evolution of the fluid and fracture fronts. The results demonstrated that considerable coupling among fluid flow, elastic deformation, and radially symmetric crack growth captures enough of the relevant physical processes. However, traditional transparent materials (PMMA, glass, resin) are homogeneous and are of limited use for understanding heterogeneous samples. Currently, 3D printing techniques applied to manufacturing, military use, the medical and food industry, and the aerospace industry have shown to be a promising tool (Berman 2012; Vaezi et al. 2013). Despite limitations of the 3D printing technique applied to rock mechanics (e.g., low strength and poor brittleness of printing material), this technique shows obvious advantages for rock mechanics studies. First, it is precise and allows flexibility for controlling the geometry of the specimen. This is especially useful in producing samples with complex components. Second, the printing process can be repeated, making it is possible to produce multiple identical specimens. These advantages in specimen preparation make 3D printing suitable for manufacturing complicated transparent 3D solids (Miller et al. 2011; Campbell and Ivanova 2013; Dal Ferro and Morari 2015).

The purpose of the research reported in this study was to observe hydrofracturing crack distribution in heterogeneous media experimentally. The transparent specimens containing heterogeneous gravel were constructed by means of the 3D printing technique. The effect of the geostress condition was tested through different confining pressures. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we outline the preparation of the 3D printing specimens, including the test of materials, reconstruction of the model, conditions and specifications. In Sect. 3, we present morphologies of the hydrofracturing cracks in the transparent specimens. The study’s conclusions are presented in Sect. 4.

2 Hydrofracturing experiments using 3D printing samples

2.1 CT identification of heterogeneous structure

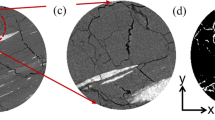

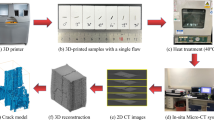

To obtain the distribution of gravel in the rock materials, the inner structures of two concrete specimens that contain gravel were probed by means of CT scanning. The concrete specimens were constructed by mixing cement and aedelforsite gravel, in which the amount and grading of the gravel was probed by detecting the gravel distribution of natural glutenite cores drilled from the Shengli SINOPEC oil field at a depth of 4000 m. The reason for using the inner structure of cement specimens for reference is that the matrix and gravels can be easily distinguished in the artificial specimens. In order to construct the 3D numerical model, a multi-thresholding segmentation method and a self-developed computer program (Ju et al. 2013, 2014b) were used to enhance and digitize the original images into binary pixels of gray and white that represented matrix and gravel, respectively. Furthermore, square images were cut into circles in order to construct cylindroid models. The whole process is shown in Fig. 1a. Moreover, we used the MIMICS© (http://biomedical.materialise.com/mimics) software as a platform to build the 3D model as shown in Fig. 1b. The model ensures the accurate characterization of the spatial distribution of the gravel because of the high precision of the CT images.

2.2 Preparation of the 3D printing samples

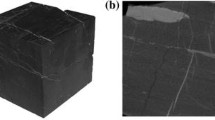

We employed the Object Connex 500 3D printer (Mueller et al. 2015) to manufacture the cylindroid samples (see Fig. 2a). The device used the Polyjet 3D printing technique (Barclift and Williams 2012; Lifton et al. 2014) for the heterogeneous sample construction. This technique involved spraying liquid photopolymer through the print head on the build tray, and then solidifying the liquid simultaneously utilizing ultraviolet light, in layer by layer fashion. This process is sketched in Fig. 2b. This technique is available for multiple printing by spraying various types of printing materials from different print heads. This approach makes it possible to construct heterogeneous objects. In addition, the 3D printer has advantages of high precision and automation (Ju et al. 2014a), with print resolution up to 600 × 600 × 1600 dpi, a dot accuracy of 10–50 μm, and molding thickness ranging 16–30 μm.

a Object Connex 500 3D printer; b schematic diagram of Polyject printing (Barclift and Williams 2012); c 3D printing samples. Samples are denoted as type i and ii

The general procedure for preparing a printing sample is as follows. First, the 3D numerical model was transited to the STL files. Second, the STL files were put into the Objet Studio software to create a 3D model. To distinguish different components of the heterogeneous model, each component, such as matrix and gravel, was put in independent STL files. From this, the Objet Studio software automatically assembled the whole model in accordance with the location coordinates of the parts. Third, the material properties were accordingly assigned to the matrix and particles in line. Using the Objet Studio, we were able to set the additional printing parameters, such as the material properties of contact surfaces and the thickness of supporting materials, in order to finalize the printing setup. In this study, we adopted the transparent photopolymer Vero Clear to print the matrix, and white RGD to print the gravel. In the hydrofracturing experiment, an open hole was required to inject water that would fracture the sample. Therefore, the light type lattice supporting material Fullcure 705 was employed to form the open hole without fillings. The supporting material features low-transparency, loose structure, low intensity, and can be physically removed or washed through high-pressure water easily after the sample is prepared. In the end, all the data of the model were transmitted to the 3D printer. Consequently, two types of cylindroid samples were printed, which are shown in Fig. 2c and denoted as type (i) and (ii). The samples were 54 mm in diameter and 108 mm in length. A 4-mm-diameter vertical hole was left at the center of the sample with a length of 54 mm. In addition, all the surfaces of the samples were polished to make the inner structure available for observation.

It is noteworthy that the printing model is structurally complicated, Thus it is possible that parts of the resinous materials did not polymerize completely or even remained in a liquid state once the printing was completed. In addition, solidification and polymerization of the resinous printing materials are sensitive to ultraviolet light and temperature. As a result, the rigidity and strength of the printing sample may change over time. To avoid this problem, the printed samples were stored at 60 °C for 48 h in order to ensure mechanical stability of the resinous printing material. Furthermore, the physical and mechanical properties of the printing materials were tested before implementing the hydraulic fracturing tests. The measured results of Vero Clear and RGD are listed in Table 1. Accordingly, the compressive strength of Vero Clear is similar to rock material, but there is a difference between the tensile strength of the printing materials and actual rock, while RGD was even weaker than Vero Clear. In fact, there are other printing materials that have greater brittleness than those used in our experiments, such as plastic and gypsum (Jiang and Zhao 2015; Jiang et al. 2016). However, these materials were not used for two reasons. First, these materials are poorly suited for printing multiple types of materials in one sample. Second, these materials are usually opaque, while our samples had better transparency.

2.3 Triaxial hydrofracturing experiment

The experiments were performed using the triaxial hydrofracturing device at Monash University which was developed based on the triaxial apparatus (Wasantha et al. 2013). Figure 3a illustrates the assembly of the hydrofracturing system, in which the fluid was injected into the sample through a syringe pump that is capable of applying a maximum injecting pressure of 50 MPa. The triaxial pressure was applied by the loading cell which is shown in Fig. 3b. The cell was built from high tensile steel and was designed to operate at a 30 MPa maximum confining pressure. The top of the cell was placed on the base of the apparatus and the bolts were inserted and tightened. A steel brace fixed the position of the loading ram such that it stayed centered and vertical during loading. The loading frame was capable of applying an axial load of up to 245 kN. Because horizontal geostress greatly influent crack propagation (Koceir and Tiab 2000; Nasehi and Mortazavi 2013), three magnitudes of confining pressures were applied while implementing the hydrofracturing tests. The three magnitudes of confining pressure applied to the samples were 1, 3 and 5 MPa. The vertical pressures were always kept at 20 MPa. The fracturing fluid was deionized water, and it was injected at a rate of 3 mL/min in all experiments. Because 3D printing techniques make it possible to construct numerous samples with the same structure, three samples for type (i) models were prepared for all confining pressure conditions. Another two samples for type (ii) models were prepared for confining pressure of 1 and 3 MPa.

3 Experimental results and discussion

3.1 Experimental observation

Because of the transparency of the matrix, the morphology of the hydrofracturing cracks can be identified by the naked eye observing the trajectories of the tracer. However, it is still challenging to record the crack morphology clearly with camera. To achieve this goal, the samples were laid on a rotatable platform while two fluorescent lamps were fixed at two sides of the fractured sample. The best observation position was found by rotating the platform. Thus, the cracks inside the sample were clearly viewable with a digital camera from only one side.

Figure 4 illustrates the top-view and side-view photographs of the fractured samples and the injection pressure curves, respectively. It shows that the cracks emerged vertically without transverse cracks appearing and that the gravels along the crack trajectory were almost broken apart at weak strengths as shown in Table 1. When the confining pressure was 5 MPa (Fig. 4a), a bi-winged crack formed with an included angle smaller than 180°. However, once confining pressure was <5 MPa as shown in Figs. 4b, c, only a radial crack formed. Radial-crack height was confined to the region near the simulated wellbore, even in different types of samples. In addition, the initial positions of the cracks are generally the same, which is also the initial position of one branch at confining pressure of 5 MPa. It seems that there was a preferential azimuth for crack initiation near the simulated wellbore.

Note that the original crack arrested at the interface of different materials as shown in Fig. 4a and b, but a secondary crack emerged. Previous studies have implied that there were several scenarios for crack behavior as it approaches the interface between soft regions and rigid regions (Wu et al. 2004). Fracture pattern depends on the energy release rate, \(G_{1} \, = \,\frac{{K_{lC}^{2} }}{{E^{\prime}}}\), where, \(E^{\prime}\, = \,E\) and \(E^{\prime}\, = \,E\,\left( {1\, - \,U^{2} } \right)\) for plane stress and plane strain problems, respectively. Unstable crack propagation was onset as K l = K lC . The stress intensity was \(K_{l} \, = \,\sigma \sqrt {\pi a}\), where σ was the normal stress along the crack faces, and a was the length of the crack. Once the cracks exited the weaker gravel the energy release rate (G l ) tended to be zero (Nuller et al. 2001). This meant that the crack would arrest according to the Griffith criterion (Griffith 1921). However, σ became discontinuous across the interface and jumped to a value larger than the tensile strength of the rigid matrix. Thus, the high value of σ fostered the generation of a secondary crack that was oriented parallel to the original crack.

3.2 CT identification

CT technology was employed to identify the distribution of the cracks in detail. Slices of the fractured samples used in all cases are shown in Fig. 5. It is evident that the cracks initiated not only from gravel as expected but also from the matrix. In addition, it is noteworthy that the gravel was not homogeneous. Flaws can be found easily inside, but they were insufficient to break the gravel. In fact, the number and development of the faults in the gravel would enhance crack growth. Consequently, few crack would propagate through the boundary of the gravel. To assess crack volumes, the width of the cracks were measured based on the CT images. The results show that the crack width is about 600 μm under a confining pressure of 5 MPa. However, this value decreased to 400 μm when the confining pressure was lowered to 3 MPa. This suggests that the crack volume decreases with the confining pressure.

3.3 Fracture breakdown

Crack morphology is associated with the fracture breakdown pressure, which is the critical pressure during pressurization of a borehole. According to the injection-time curves in Fig. 4, the wellbore pressure drops instantaneously at a peak point, which is defined as the breakdown pressure and marks onset of unstable fracture propagation. In general, the rock is assumed homogeneous and isotropic, following Hooke’s law of linear elastic behavior. According to the Hubbert-Willis expression (Hubbert and Willis 1972), the condition for crack initiation is reached when,

The 3D printing samples are a desirable impermeable media with no pores contained. Therefore, the pore pressure is zero (P 0 = 0). According to the experimental results, the tensile strength, T o, of the matrix is 38 MPa, compared to 33 MPa for the gravel. The experimental and theoretical results plotted in Fig. 6 illustrate that the experimental breakdown pressures follow a variation trend similar to theoretical breakdown pressures, but that the values appear much lower in the experimental results. In the heterogeneous medium, the gravel has significant influence on stress distributions, which leads to weakened regions in the crack initiation. Mathematically, the linear variation of the breakdown pressure obtained in the experiments could be expressed as,

Comparing Eq. (2) with Eq. (1), the expression yields,

It seems that heterogeneity enhances the influence of confining pressure on the breakdown pressure of cracks. The smaller the confining pressure, the more difficult it is to achieve the theoretical breakdown value. Consequently, heterogeneity of the material would have greater effect on the initiation of the cracks.

4 Conclusions

This study reports a series of hydrofracturing tests designed to observe the hydrofracturing crack distribution in heterogeneous media based on transparent samples. Advanced 3D printing techniques were employed to construct heterogeneous samples that represented accurate distribution of gravel. To probe the effect of confining pressure on hydrofracturing crack pattern, three confining pressure states were utilized. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Geostress has significant influence on the characteristics of hydrofracturing cracks in the heterogeneous media. When the confining pressure is high (i.e., 5 MPa), a bi-winged crack formed. However, when the confining pressure was <5 MPa, only a radial crack formed. It seems that hydrofracturing cracks are reduced as the confining pressure increases in the heterogeneous media.

-

(2)

The heterogeneous gravel led to segmentation of the cracks and significantly affected the initiation of cracks by changing the stress state around the simulated wellbore.

It should be noted that the mechanical properties of the 3D printing samples exhibits a certain degree of deviation, despite the preliminary attempts in this study that employed 3D display and visualization of crack patterns under the coupled effect of heterogeneous gravel and confining pressure. Thus, further research will aim at improving the 3D printing materials to make their properties approach that of actual rocks. With such improvement, we would return to the hydrofracturing tests to verify and characterize crack patterns.

References

Al-Busaidi A, Hazzard J, Young R (2005) Distinct element modeling of hydraulically fractured Lac du Bonnet granite. J Geophys Res 110(110):351–352

Barclift MW, Williams CB (2012) Examining variability in the mechanical properties of parts manufactured via polyjet direct 3D printing

Berman B (2012) 3-D printing: the new industrial revolution. Bus Horiz 55(2):155–162

Bunger AP, Gordeliy E, Detournay E (2013) Comparison between laboratory experiments and coupled simulations of saucer-shaped hydraulic fractures in homogeneous brittle-elastic solids. J Mech Phys Solids 61(7):1636–1654

Campbell TA, Ivanova OS (2013) 3D printing of multifunctional nanocomposites. Nano Today 8(2):119–120

Castano AF, Sondergeld CH, Rai CS (2010) Estimation of uncertainty in microseismic event location associated with hydraulic fracturing. In: Tight gas completions conference, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 135325

Cipolla CL, Warpinski NR, Mayerhofer MJ (2008) Hydraulic fracture complexity: diagnosis remediation and explotation. SPE Asia Pacific oil and gas conference and exhibition, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 115771

Cipolla C, Maxwell S, Mack M, Downie R (2012) A practical guide to interpreting microseismic measurements. In: North American unconventional gas conference and exhibition, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 144067

Dal Ferro N, Morari F (2015) From real soils to 3D-printed soils: reproduction of complex pore network at the real size in a silty-loam soil. Soil Sci Soc Am J 79(4):1008–1017

Fouche O, Wright H, Cleac’H JML, Pellenard P (2004) Fabric control on strain and rupture of heterogeneous shale samples by using a non-conventional mechanical test. Appl Clay Sci 26(1):367–387

Garcia X, Nagel N, Zhang F, Sanchez-Nagel M, Lee B (2013) Revisiting vertical hydraulic fracture propagation through layered formations—a numerical evaluation. In: 47th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 2013-203

Griffith AA (1921) The phenomena of rupture and flow in solids. Philos Trans R Soc Lond 221:163–198

Gu H, Siebrits E, Sabourov A (2008) Hydraulic Fracture modeling with bedding plane interfacial slip. In: SPE Eastern Regional/AAPG Eastern section joint meeting, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 117445

Guo T, Zhang S, Qu Z, Zhou T, Xiao Y, Gao J (2014) Experimental study of hydraulic fracturing for shale by stimulated reservoir volume. Fuel 128(14):373–380

Hampton J C, Hu D, Matzar L, Gutierrez M (2014) Cumulative volumetric deformation of a hydraulic fracture using acoustic emission and Micro-CT imaging. In: 48th U.S. rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 2014-7041

He S, Jiang Y, Conrad JC, Qin G (2015) Molecular simulation of natural gas transport and storage in shale rocks with heterogeneous nano-pore structures. J Petrol Sci Eng 133:401–409

Hiyama M, Shimizu H, Ito T, Tamagawa T, Tezuka K (2013) Distinct element analysis for hydraulic fracturing in shale-effect of brittleness on the fracture propagation. In: 47th U.S. rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 2013-659

Hubbert MK, Willis DGW (1972) Mechanics of hydraulic fracturing. Mem Am Assoc Pet Geol 18:153–163

Jiang C, Zhao GF (2015) A preliminary study of 3D printing on rock mechanics. Rock Mech Rock Eng 48(3):1041–1050

Jiang C, Zhao GF, Zhu J, Zhao YX, Shen L (2016) Investigation of dynamic crack coalescence using a gypsum-like 3D printing material. Rock Mechanics & Rock Engineering. 1–16

Johnston R, Shrallow J (2011) Ambiguity in microseismic monitoring. In: 2011 SEG annual meeting, Society of Exploration Geophysicists, SEG 2011-1514

Ju Y, Xing M, Sun H (2013) Computer program for extracting and analyzing fractures in rocks and concretes. Software Copyright Rigistration #0530646, Beijing (in Chinese)

Ju Y, Xie H, Zheng Z, Lu J, Mao L, Gao F, Peng R (2014a) Visualization of the complex structure and stress field inside rock by means of 3D printing technology. Chin Sci Bull 59(36):5354–5365

Ju Y, Zheng J, Epstein M, Sudak L, Wang J, Zhao X (2014b) 3D numerical reconstruction of well-connected porous structure of rock using fractal algorithms. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 279(9):212–226

Kaswiyanto F Y, Arif I, Simangunsong GM (2014) Physical and numerical modeling to predict fracture initiation on hydraulic fracturing. In: Asian rock mechanics symposium

Koceir M, Tiab D (2000) Influence of stress and lithology on hydraulic fracturing in Hassi Messaoud reservoir, Algeria. In: SPE/AAPG Western Regional meeting, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 62608

Kresse O, Cohen C, Weng X, Wu R, Gu H, 2011. Numerical modeling of hydraulic fracturing in naturally fractured formations. In: Proceedings of the 45th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 11-363

Kresse O, Weng X, Gu H, Wu R (2013) Numerical modeling of hydraulic fractures interaction in complex naturally fractured formations. Rock Mech Rock Eng 46(3):555–568

Li L, Meng Q, Wang S, Li G, Tang C (2013) A numerical investigation of the hydraulic fracturing behaviour of conglomerate in glutenite formation. Acta Geotech 8(6):597–618

Lifton VA, Lifton G, Simon S (2014) Options for additive rapid prototyping methods (3D printing) in MEMS technology. Rapid Prototyp J 20(5):403–413

Maxwell SC, Cipolla CL (2011) What does microseismicity tell us about hydraulic fracturing? In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 146932

Maxwell SC, Weng X, Kresse O, Rutledge J (2013) Modeling Microseismic Hydraulic Fracture Deformation. In: spe annual technical conference and exhibition, Society of Petroleum Engineers, SPE 166312

Maxwell S, Chorney D, Goodfellow S (2015) Microseismic geomechanics of hydraulic-fracture networks: insights into mechanisms of microseismic sources. Lead Edge 34(8):904–910

Miller BW, Moore JW, Barrett HH, Fryé T, Adler S, Sery J, Furenlid LR (2011) 3D printing in X-ray and gamma-ray imaging: a novel method for fabricating high-density imaging apertures. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res 659(1):262–268

Mueller J, Shea K, Daraio C (2015) Mechanical properties of parts fabricated with inkjet 3D printing through efficient experimental design. Mater Des 86:902–912

Nasehi MJ, Mortazavi A (2013) Effects of in situ stress regime and intact rock strength parameters on the hydraulic fracturing. J Petrol Sci Eng 108(4):211–221

Nuller B, Ryvkin M, Chudnovsky A, Dudley J, Wong G (2001) Crack interaction with an interface in laminated elastic media. In: 38th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 0289

Renard F, Bernard D, Desrues J, Ougier-Simonin A (2009) 3D imaging of fracture propagation using synchrotron X-ray microtomography. Earth Planet Sci Lett 286(2):285–291

Sarmadivaleh M, Rasouli V (2015) Test design and sample preparation procedure for experimental investigation of hydraulic fracturing interaction modes. Rock Mech Rock Eng 48(1):93–105

Shimizu H, Murata S, Ishida T (2011) The distinct element analysis for hydraulic fracturing in hard rock considering fluid viscosity and particle size distribution. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 48(5):712–727

Shimizu H, Hiyama M, Ito T, Tamagawa T, Tezuka K (2014) Flow-coupled DEM simulation for hydraulic fracturing in pre-fractured rock. In: 48th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 7365

Stanchits S, Burghardt J, Surdi A, Edelman E, Suarez-Rivera R (2014) Acoustic emission monitoring of heterogeneous rock hydraulic fracturing. In: 48th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 2014-7775

Tang C, Tham L, Lee P, Yang T, Li L (2002) Coupled analysis of flow, stress and damage (FSD) in rock failure. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci 39(4):477–489

Vaezi M, Seitz H (1957) Yang S (2013) Erratum to: a review on 3D micro-additive manufacturing technologies. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 67:5–8

van der Baan M, Eaton D, Dusseault M, 2013. Microseismic monitoring developments in hydraulic fracture stimulation. In: ISRM international conference for effective and sustainable hydraulic fracturing, International Society for Rock Mechanics, ISRM-ICHF-2013-003

Wang Y (2013) Numerical modelling of heterogeneous rock breakage behaviour based on texture images. Miner Eng 74:130–141

Wang S, Sloan S, Fityus S, Griffiths D, Tang C (2013) Numerical modeling of pore pressure influence on fracture evolution in brittle heterogeneous rocks. Rock Mech Rock Eng 46(5):1165–1182

Wang K, Zhang Q, Xia X, Wang L, Liu X (2015) Analysis of hydraulic fracturing in concrete dam considering fluid–structure interaction using XFEM-FVM model. Eng Fail Anal 57(1):399–412

Warpinski N, 2014. A review of hydraulic-fracture induced microseismicity. In: 48th US rock mechanics/geomechanics symposium, American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 2014-7774

Wasantha PLP, Darlington WJ, Ranjith PG (2013) Characterization of mechanical behaviour of saturated sandstone using a newly developed triaxial apparatus. Exp Mech 53:871–882

Wu RT (2006) Some fundamental mechanisms of hydraulic fracturing. Dotoral thesis, Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia

Wu H, Chudnovsky A, Dudley J, Wong G (2004) A map of fracture behavior in the vicinity of an interface. In: 6th North America rock mechanics symposium (NARMS), American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 04-620

Wu H, Golovin E, Shulkin Y, Chudnovsky A, Dudley J, Wong G (2008) Observations of hydraulic fracture initiation and propagation in a brittle polymer. In: 42nd U.S. rock mechanics symposium. American Rock Mechanics Association, ARMA 321

Yang T, Tham L, Tang C, Liang Z, Tsui Y (2004) Influence of heterogeneity of mechanical properties on hydraulic fracturing in permeable rocks. Rock Mech Rock Eng 37(4):251–275

Zhang X, Jeffrey RG, Thiercelin M (2007) Deflection and propagation of fluid-driven fractures at frictional bedding interfaces: a numerical investigation. J Struct Geol 29(3):396–410

Zou YS, Zhang SC, Zhou T, Zhou X, Guo TK (2016) Experimental investigation into hydraulic fracture network propagation in gas shales using CT scanning technology. Rock Mech Rock Eng 49(1):33–45

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 51374213 and 51674251), National Natural Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (Grant 51125017), Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 51421003), Fund for Innovative Research and Development Group Program of Jiangsu Province (Grant 2014-27), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (Grant PAPD 2014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, P., Ju, Y., Ranjith, P.G. et al. Visual representation and characterization of three-dimensional hydrofracturing cracks within heterogeneous rock through 3D printing and transparent models. Int J Coal Sci Technol 3, 284–294 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-016-0145-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-016-0145-y