Abstract

Objective

The evolutionary-contingency hypothesis, which suggests that preferences for leaders are context-dependent, has found relatively consistent support from research investigating leadership decisions based on facial pictures. Here, we test whether these results transfer to leadership decisions based on voice recordings. We examined how dominance and trustworthiness perceptions relate to leadership decisions in wartime and peacetime contexts and whether effects differ by a speaker’s gender. Further, we investigate two cues that might be related to leadership decisions, as well as dominance and trustworthiness perceptions: voice pitch and strength of regional accent.

Methods

We conducted a preregistered online study with 125 raters and recordings of 120 speakers (61 men, 59 women) from different parts in Germany. Raters were randomly distributed into four rating conditions: dominance, trustworthiness, hypothetical vote (wartime) and hypothetical vote (peacetime).

Results

We find that dominant speakers were more likely to be voted for in a wartime context while trustworthy speakers were more likely to be voted for in a peacetime context. Voice pitch functions as a main cue for dominance perceptions, while strength of regional accent functions as a main cue for trustworthiness perceptions.

Conclusions

This study adds to a stream of research that suggests that (a) people’s voices contain important information based on which we form social impressions and (b) we prefer different types of leaders across different contexts. Future research should disentangle effects of gender bias in leadership decisions and investigate underlying mechanisms that influence how people’s voices contribute to achieving social status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leadership – the highest position of status, power and hierarchy in social groups – is an ubiquitous phenomenon and sometimes considered as being the most important topic in human sciences (Hogan & Kaiser, 2005; Van Vugt et al., 2008). Who we choose as a leader in a social group matters, as it influences important outcomes for the group and each individual. For example, high social status is associated with fitness and reproductive benefits, as well as with higher life satisfaction and well-being (e.g. Anderson et al., 2012; Von Rueden et al., 2011). Further, our leadership choices directly influence performance and success as a group, as organizations with good leaders prosper and thrive (Hogan & Kaiser, 2005). Who we choose as our leader can even become a matter of life and death, when it comes to wartime scenarios (Van Vugt et al., 2008).

The Evolutionary-Contingency Hypothesis

How do we select our leaders and decide whom to follow? Previous research suggests that, when choosing a group leader, people often rely on physical cues, such as facial appearance or body shape. For example, politicians who look “good” or “more competent” are supported by politically uninformed voters (Lenz & Lawson, 2011) and perceptions of dominance, trustworthiness, and attractiveness predict managerial pay awards (Fruhen et al., 2015). Further, physically formidable, as well as attractive people seem to reach a higher social status (Anderson et al., 2001; Lukaszewski et al., 2016). However, it has been argued that not all leadership decisions are the same, as humans are sensitive to oscillations between cooperation and conflict and that who they prefer as a leader might change across cooperative or competitive environments. In line with this assumption, the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis was proposed. This hypothesis suggests that preferences for leaders might be context-dependent (e.g., changing across wartime vs. peacetime scenarios), contingent upon the match of different cues and follower needs and may have evolved to deal with specific group challenges (Van Vugt et al., 2008). More precisely, in a time of conflict and intergroup competition (e.g., wartime) people may select leaders that appear more dominant, or even aggressive, focusing on maintaining and creating advantages over other groups. In contrast, in a time of cooperation (e.g., peacetime), people may rather select leaders that appear more prosocial and trustworthy, focusing on maintaining and creating positive intergroup relations (Spisak, Homan et al., 2012, Van Vugt & Grabo, 2015).

Leadership Judgments Based on Faces

Supportive evidence for context-dependent leadership preferences stems from research investigating leadership decisions based on facial pictures. Multiple studies have reported that facial perceptions of dominance or trustworthiness can guide leadership decisions with context-specific effects. More precisely, more dominant looking faces were preferred as leaders in hypothetical wartime scenarios, whereas more trustworthy looking faces were preferred as leaders in hypothetical peacetime scenarios (Ferguson et al., 2019; Little et al., 2007, 2012; Spisak, Dekker et al., 2012; Spisak, Homan Spisak et al., 2012a, b; Van Vugt & Grabo, 2015). Importantly, dominance and trustworthiness perceptions are only weakly related and are based on different facial cues (Oosterhof & Todorov, 2008; Van Vugt & Grabo, 2015). For example, facial masculinity serves as a cue in dominance perceptions (e.g., Van Vugt & Grabo 2015), while happy facial expressions serve as a cue in trustworthiness perceptions (e.g., Jaeger & Jones 2022). However, whereas there is compelling evidence for the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis from research on facial perceptions, research on context-specific leadership decisions based on other physical characteristics is rather scarce.

Voice Perception and Leadership Judgments

One important characteristic on which we form social evaluations is the voice. Peoples’ voices have a strong impact on socially relevant impressions. When talking to a person on the phone, or listening to the radio or a podcast, we immediately make inferences about the other person, such as their gender or age, but also their personality (Belin et al., 2011; McAleer et al., 2014a, b), even if the other person speaks in a different language (Baus et al., 2019). Similarly to face perceptions, voice perceptions can be summarized on a two-dimensional “social voice space” with axes mapping trustworthiness (valence) and dominance (McAleer et al., 2014a, b; Shiramizu et al., 2022). Again, research has also shown that different cues underly these orthogonal dimensions. The most salient cue that drives impressions of dominance is the voice pitch (also known as fundamental frequency or F0) – the rate of vocal fold vibrations that influences how deep a voice sounds (e.g., Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Puts et al., 2006; Schild et al., 2020). Voice pitch directly impacts the perceptions of a speaker’s power and has been discussed as being an honest signal of social status (Aung & Puts, 2020) as it is linked to a speaker’s body morphology, strength and hormonal profiles (e.g., Aung & Puts, 2019; Cartei et al., 2014; Schild et al., 2020). Lower, more masculine voice pitch is generally preferred in both, male and female leaders (Anderson & Klofstad, 2012; Klofstad et al., 2012). It has been reported that people are more likely to vote for politicians with lower voice pitch (Klofstad et al., 2016; Tigue et al., 2012) and that CEOs voice pitch is associated with their own and the success of their organization (Mayew et al., 2013). Importantly, voices do even have a larger influence on overall dominance perceptions than faces (Rezlescu et al., 2015; Mileva et al., 2018) and a first study suggests that voice pitch is actually related to people’s self-reported dominance (Stern et al., 2021).

While the link between voice pitch and dominance perceptions is very robust across studies and contexts, voice pitch is only weakly related to perceptions of trustworthiness. Previous studies reported mixed findings, with the significance and direction of effects depending on different contexts (e.g. mating context vs. economic context) and research designs (e.g. natural vs. manipulated stimuli; as reviewed in Schild, Stern et al., 2020). Overall, it seems as if voice pitch is rather weakly related to perceptions of general trustworthiness (O’Connor & Barclay, 2017; Schild et al., 2019), or actual self-reported trustworthiness (Schild, Stern et al., 2020). However, these findings might not be generalizable across genders, as most previous studies only focused on men.

Next to vocal characteristics like voice pitch, speech also includes sociolinguistic features that provide information about an individual’s group membership. For example, listeners can accurately judge a speaker’s social class (Kraus et al., 2019; Ryan & Bulik, 1982) or ethnicity (Szakay, 2012; Thomas & Reaser, 2004) from brief speech recordings. As group membership plays a crucial role for trust decisions and perceptions of trustworthiness (e.g., Platow et al., 2012), one might expect that sociolinguistic features that signal group membership are also related to trustworthiness perceptions. Indeed, prior research finds that children are more likely to trust native accented speakers (Kinzler et al., 2011) and that speakers with standard accents are more likely to be trusted than speakers with regional accents in economic games (Torre et al., 2018). At the same time, articulatory patterns, such as regional accent, might also be related to dominance perceptions, as they have been reported to be associated with traits like body height or testosterone levels in men, that are also related to dominance, status, and election outcomes (Kempe et al., 2013).

In summary, there is already compelling evidence for the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis for leadership decisions based on faces, whereas the hypothesis has not yet been tested for leadership decisions based on other characteristics, such as voices. Nevertheless, previous research suggests that, in line with dominance perceptions from faces, more masculine voices, indicated by lower voice pitch, are perceived as being more dominant. In contrast, perceptions of trustworthiness based on voices might rather rely on sociolinguistic features, such as regional accents. The aim of the current study is to test the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis for leadership decisionsFootnote 1 based on dominance and trustworthiness perceptions of men’s and women’s voices.

Hypotheses

First, we expect to replicate previous findings regarding the relationship between lower voice pitch and perceptions of higher dominance. Thus, we hypothesize that voice pitch will be negatively related to dominance ratingsFootnote 2 (Hypothesis 1). Second, we expect to find support for the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis and hypothesize that more trustworthy sounding voices are more likely to be voted for in the (hypothetical) peacetime scenario, while dominant sounding voices are more likely to be voted for in the (hypothetical) war-time scenario (Hypothesis 2). Third, we expect that voice pitch, as a main cue of dominance, is more strongly related to votes in the (hypothetical) wartime scenario (as compared to the hypothetical peacetime scenario) (Hypothesis 3).

In addition, we will investigate a number of research questions in an exploratory manner. More precisely, we will investigate whether perceptions of dominance and trustworthiness relate to a speaker’s strength of regional accent. Further, we test if strength of regional accent, as a main cue of trustworthiness, is more strongly related to votes in the (hypothetical) peace-time scenario (as compared to the wartime scenario). We will investigate whether perceptions of dominance and trustworthiness differ according to a speaker’s gender. We will further investigate if leadership decisions across different contexts differ for male and female voices. There is still a gender bias in real-life leadership, in that way more men achieve important leadership positions (e.g. politicians or organizational leaders). Voice pitch is highly sexually dimorphic, with men’s voice pitch being much lower than women’s voice pitch. In fact, sex differences in voice pitch are as high as 5 SDs, with almost non-overlapping distributions (Puts et al., 2012). On this basis, researchers previously suggested that large sex differences in voice pitch might be one explanation why men are more successful in obtaining leadership positions (Klofstad et al., 2012). Nevertheless, we did not formulate specific hypotheses regarding this research questions based on previously reported mixed findings regarding different variables assessed in the current study. For example, lower voice pitch seems to be beneficial for leadership decisions and dominance perceptions in men and women (Anderson & Klofstad, 2012; Klofstad et al., 2012), but some studies only focused on male stimuli (Schild et al., 2020; Tigue et al., 2012) and evidence regarding trustworthiness is rather method- and context-dependent (Schild et al., 2020).

Method

The study was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/zfywm). Open data, analysis script and supplementary material are available via: https://osf.io/ztwm4/.

Stimuli

We used standardized voice recordings from the Jena Speaker Set (JESS; Zäske et al., 2019). The database consists of recordings of 120 speakers (61 men, 59 women) who provide an extensive set of stimuli, including short sentences, semi-spontaneous speech and vowels. For this study we used recordings of the short sentence “Der Fahrer lenkt den Wagen.” (“The driver steers the car.”) as the database provides evaluations of the speaker’s strength of regional accent (“Please assess how weak/strong the regional accent of the following speakers is.” on a Likert scale from 1 to 6, 1 being ‘very weak’, 6 being ‘very strong’) for this particular sentence by 24 raters. Further, by using the same sentence for all speakers, we can assure that the influence of speech content does not vary. For further information about the JESS, such as recording set-up, please see Zäske et al., (2019).

Procedure and Participants

We conducted an online study using the open-source survey framework formr (www.formr.org; Arslan et al., 2019; Arslan & Tata, 2019). Participants were recruited through the local participant database of the University of Siegen and a mailing list for psychology students at the University of Bremen. Students received course credit for participation. Further, advertisements were also posted on social media platforms (with participants not being enrolled at the Universities of Siegen or Bremen not receiving any compensation). Participants were randomly distributed into four rating conditions: dominance, trustworthiness, hypothetical vote (wartime) and hypothetical vote (peacetime). In each condition, participants listened to and rated all 120 recordings in randomized order. Participants were allowed to take breaks to avoid rater fatigue. Rating items were presented as:

-

1.

Dominance: “How dominant does this person appear?” (on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, 1 being ‘not dominant at all’, 7 being ‘very dominant’).

-

2.

Trustworthiness: “How trustworthy does this person appear?” (on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, 1 being ‘not trustworthy at all’, 7 being ‘very trustworthy’).

-

3.

Hypothetical vote (wartime): “Imagine that there is a war going on in your country. There are political elections coming up and below you are presented with audio files of possible candidates. For each candidate, indicate how likely it is that you would vote for that candidate. How likely is it that you would vote for this person?” (on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, 1 being ‘very unlikely’, 7 being ‘very likely’).

-

4.

Hypothetical vote (peacetime): “Imagine that you are in a peaceful situation, politically and socially. There are political elections coming up and below you are presented with audio files of possible candidates. For each candidate, indicate how likely it is that you would vote for that candidate. How likely is it that you would vote for this person?” (on a Likert scale from 1 to 7, 1 being ‘very unlikely’, 7 being ‘very likely’).

Overall, 128 participants completed the study. In line with our preregistration, we excluded 3 participants prior to any data analyses because they provided the same rating in more than 75% of cases, resulting in a final sample of 125 participants (ndominance = 34, ntrustworthiness = 30, npeace = 31, nwar = 30). Participants were rather homogeneous with respect to gender (75.20% female, 24.00% male, 0.80% other). Their average age was 24.82 years (SD = 8.87 years). Both dominance and trustworthiness ratings were averaged across participants, resulting in an average dominance and an average trustworthiness score for each recording. Interrater agreement was very high for both dominance (α = 0.92) and trustworthiness ratings (α = 0.88).

Voice Measurements

We measured voice pitch (F0) with default settings for each recording using Voicelab (Feinberg & Cook, 2020).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses in the current manuscript were calculated with the statistic software R 4.1.2 (R core Team, 2021). Hypotheses tests were conducted in line with our preregistration.

Results

Gender Differences

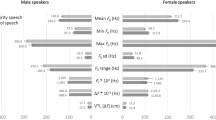

Male voices (M = 3.65) were perceived as being more dominant than female voices (M = 3.25; d = -0.61, t (116.17) = 3.32, p = .001, 95%CIs = [-0.98, -0.23]). There was no significant difference between male voices (M = 4.30) and female voices (M = 4.50) in trustworthiness ratings (d = 0.32, t (115.62) = -1.74, p = .085, 95%CIs = [-0.04, 0.68]). Male speakers (M = 106.83) spoke with a lower voice pitch than female speakers (M = 191.08; d = 4.04, t (89.156) = -21.73, p < .001, 95%CIs = [3.23, 4.84]), while there was no significant difference between male voices (M = 3.06) and female voices (M = 2.87) in strength of regional accent (d = -0.27, t (113.57) = 1.45, p = .150, 95%CIs = [-0.63, 0.10]). Figure S1 provides an overview of the gender differences in the key variables.

Please note that in our preregistration we registered separate models for male and female voices, mainly due to concerns of statistical power. However, to allow statistical rather than mainly descriptive differences between male and female voices, we investigated gender differences by modelling interaction effects of all of our predictor variables, including adding gender to the interaction effects reported below. These analyses showed substantial gender differences, as suggested by two-way and three-way interaction effects. As these models lead to the same conclusions and to facilitate interpretability we report the separate models in the manuscript but provide the results of the additional models in the supplementary material.

Voice Pitch and Perceptions

Perceptions of dominance and trustworthiness were not significantly related (r = − .04, p = .630, 95%CIs = [-0.14 – 0.22]). Perceptions of dominance were negatively related to voice pitch for both male voices (r = − .37, p = .003, 95%CIs = [-0.57 – − 0.13]) and female voices (r = − .50, p < .001, 95%CIs = [-0.67 – − 0.28]), indicating that voices with lower pitch were perceived as being more dominant, in line with Hypothesis 1. Perceptions of trustworthiness were negatively related to voice pitch for male voices (r = − .28, p = .031, 95%CIs = [-0.49 – − 0.03]), but positively related to voice pitch for female voices (r = .30, p = .018, 95%CIs = [0.06 – 0.52]). These results suggest that women with higher, but men with lower voice pitch were perceived as being more trustworthy. Relations between voice pitch and perceptions are summarized by gender in Fig. 1.

Strength of Regional Accent and Perceptions

Perceptions of dominance were not significantly related to strength of regional accent for both male voices (r = − .15, p = .247, 95%CIs = [-0.39 – − 0.11]) and female voices (r = .07, p = .583, 95%CIs = [-0.18 – 0.32]). In contrast, perceptions of trustworthiness were strongly negatively related to strength of regional accent for both male voices (r = − .69, p < .001, 95%CIs = [-0.80 – − 0.53]) and female voices (r = − .72, p < .001, 95%CIs = [-0.82 – 0.56]). These results suggest that speakers with a stronger regional accent were perceived as being less trustworthy. Relations between strength of regional accent and perceptions are summarized by gender in Fig. 2.

Dominance, Trustworthiness, and Hypothetical Votes

To investigate the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis, we ran two linear mixed effects models, one for male voices and one for female voices, with hypothetical vote as the dependent variable and average dominance rating, average trustworthiness rating, and leadership context as predictors. We also included interactions between average dominance rating and leadership context and between average trustworthiness rating and leadership context. Random intercepts were specified for the raters as well as for the voices. Further, we specified random slopes for dominance and trustworthiness ratings varying per raterFootnote 3. For male voices, average dominance ratings and context interacted in predicting hypothetical votes (β = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.05–0.25], p = .003). Average trustworthiness ratings and context interacted in predicting hypothetical votes(β = -0.21, 95% CI = [-0.33 – -0.10], p < .001). For female voices, average dominance ratings and context interacted in predicting hypothetical votes (β = 0.14, 95% CI = [0.05–0.23], p = .004). Average trustworthiness ratings and context interacted in predicting hypothetical votes(β = -0.25, 95% CI = [-0.40 – -0.10], p = .002). These results suggest that, for male and female speakers, voices that were perceived as being more dominant were preferred as leaders in a wartime context, while voices that were perceived as being more trustworthy were preferred as leaders in a peacetime context. Hypothesis 2 was thus supported. Further, both models revealed a main effect for trustworthiness in male and female speakers, in that voices that were perceived as being more trustworthy were preferred as leaders in general (men: β = 0.48, 95% CI = [0.39–0.58], p < .001, women: β = 0.41, 95% CI = [0.29–0.52], p < .001). Perceptions of higher dominance (β = 0.13, 95% CI = [0.06–0.21], p = .001), as well as peacetime voting context (β = -0.23, 95% CI = [-0.45 - -0.01], p = .040) were significantly related to likelihood of voting in female speakers, but not in male speakers (dominance: β = -0.05, 95% CI = [-0.14–0.03], p = .218, context: β = 0.09, 95% CI = [-0.20–0.14], p = .729). Results are summarized in Fig. 3. Full output of the mixed models is documented in the supplementary material.

Marginal effects plots for the interaction between condition and dominance or trustworthiness in predicting likelihood of vote

Note: Marginal effects plots for the interaction between condition and dominance in predicting likelihood of vote (A: male voices, C: female voices). Marginal effects plots for the interaction between condition and trustworthiness in predicting likelihood of vote (B: male voices, D: female voices). Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Voice Pitch, Regional Accent, and Hypothetical Votes

As a next step, we investigated whether voice pitch or the strength of regional accent, as well as their interaction with leadership context, were associated with the likelihood to vote for a speaker. For this purpose, we first ran two linear mixed effects models, one for male voices and one for female voices, with hypothetical votes as the dependent variable and voice pitch, leadership context and their interaction as predictors. Random intercepts were specified for the raters as well as for the voices. Further, we specified random slopes for voice pitch varying per rater.

For male voices, the interaction between voice pitch and context was not significantly related to hypothetical votes (β = -0.05, 95% CI = [-0.12–0.02], p = .182). For female voices, voice pitch and context did interact significantly in predicting hypothetical votes(β = -0.26, 95% CI = [-0.38 – -0.14], p < .001), indicating that participants were more likely to vote for women with lower voice pitch, but only in the wartime context. Hypothesis 3 was thus only supported for female voices. However, there was a main effect of voice pitch in male voices (β = -0.14, 95% CI = [-0.25–0.02], p = .019), suggesting that participants were generally more likely to vote for men with a lower voice pitch (this effect was not significant in female speakers, β = 0.07, 95% CI = [-0.06–0.19], p = .277). The main effect for leadership context was not significant in male, as well as in female voices. Results are summarized in Fig. 4. Full output of the mixed models is documented in the supplementary material.

Then, as further exploratory analyses, we ran two additional linear mixed effects models, one for male voices and one for female voices, with hypothetical votes as the dependent variable and strength of accent, leadership context and their interaction as predictors. Random intercepts were specified for the raters as well as for the voices. Further, we specified random slopes for strength of accent varying per rater. For both genders, the strength of regional accent had negative associations with their likelihood to be voted for (male voices: β = -0.41, 95% CI = [-0.51 – -0.32], p < .001; female voices: β = -0.32, 95% CI = [-0.44 – -0.19], p < .001). Further, for male voices (β = 0.13, 95% CI = [-0.02–0.24], p = .023), as well as for female voices (β = 0.24, p = .001), strength of accent and context interacted significantly in predicting hypothetical votes. Female speakers were less likely to be voted for in the wartime context (β = -0.23, 95% CI = [-0.45 – -0.01], p = .040), whereas there was no significant leadership context main effect in male speakers (β = 0.06, 95% CI = [-0.17 – -0.30], p = .607). Results are summarized in Fig. 5. Full output of the mixed models is documented in the supplementary material.

Discussion

The evolutionary-contingency hypothesis suggests that preferences for leaders are context-dependent: in a wartime context, people are more likely to select leaders that appear more dominant, whereas in a peacetime context, people rather select leaders that appear more trustworthy. Previous studies have already reported evidence for this hypothesis regarding leadership judgments based on facial pictures. Here, we provide first evidence for this hypothesis for leadership judgments from voice recordings. We further replicated previous findings linking voice pitch to dominance perceptions and showed that regional accent is related to trustworthiness perceptions. In addition, we investigated whether our results differ by speaker’s gender.

Dominance, Trustworthiness and Leadership Decisions from Voices

In line with our Hypothesis 1, lower pitched voices were perceived as being more dominant in male and female speakers, supporting comparable findings in previous research (Hodges-Simeon et al., 2010; Puts et al., 2006; Schild et al., 2020). Regarding trustworthiness, lower pitched voices were perceived as being more trustworthy in male speakers, but less trustworthy in female speakers. These results suggest that trustworthiness perceptions in voices may differ by speaker’s gender, potentially explaining mixed findings in previous research (as reviewed in Schild, Stern et al., 2020). In line with the evolutionary-contingency hypothesis and our preregistered Hypothesis 2, male and female speakers that were perceived as being more dominant were more likely to be voted for in a wartime context. In contrast, they were more likely to be voted for in a peacetime context when their voices were perceived as being more trustworthy. Thus, people draw inferences about other people’s leadership potential, only based on their voices. These leadership preferences based on voices are context-dependent in exactly the same way as leadership preferences from faces (Ferguson et al., 2019; Little et al., 2007, 2012; Spisak, Dekker et al., 2012; Spisak, Homan Spisak et al., 2012a, b; Van Vugt & Grabo, 2015). Our findings are further in line with previous studies reporting that people generally aim for male leaders with lower voice pitch (e.g. Tigue et al., 2012). However, for the selection of female leaders, leadership decisions based on voice pitch are context-dependent and differ between wartime and peacetime scenarios. More precisely, participants were more likely to vote for women with lower voice pitch, but only in the wartime context, partly supporting Hypothesis 3 (as the interaction effect between voice pitch and context was not significant for male speakers).

Voice Pitch and Regional Accent Influence Social Perceptions

Comparable to face perception, different cues seem to affect perceptions of dominance and trustworthiness from voices. Our results suggest that voice pitch is important for dominance perceptions, whereas the strength of regional accent might be the strongest predictor of trustworthiness perceptions. While voice pitch explained 25% variance of dominance perceptions in female voices and 14% of variance in male voices, it explained less variance of trustworthiness perceptions (9% in female voices, 8% in male voices). In contrast, regional accent explains as much as 48% variance of trustworthiness perceptions in male voices and 52% in female voices, whereas it only explains very little variance in dominance perceptions (2% in male voices, less than 1% in female voices).

One potential reason why lower voice pitch is associated with higher dominance perceptions might be that lower voice pitch is associated with masculinity. More precisely, as voice pitch is highly sexually dimorphic (Puts et al., 2012), we perceive lower pitched voices as being more masculine. A link between masculinity and dominance perceptions has also been shown in face perception research (e.g., Oosterhof & Todorov 2008). Following Van Vugt and Grabo’s (2015) reasoning on leadership decisions based on facial masculinity, lower voice pitch might have been reliably associated with leadership in ancestral human environments. However, when looking for a trustworthy leader, people might rather not strongly rely on a speaker’s voice pitch. As reported above, the most important cue for trustworthiness perceptions based on voices seems to be a speaker’s regional accent. Interestingly, based on the location of where the voice samples were recorded, the regional accents may have signaled that some speakers were from eastern Germany, while ratings were performed by participants from western Germany. Thus, while speakers and raters were likely natives in the same language, the regional accent might have signaled that they do not live in the same region. As previous research suggests that people perceive outgroup members as being less trustworthy than members of their ingroup (e.g. Vermue et al., 2018), this regional accent may already have led to perceiving speakers with a stronger regional accent as part of an outgroup. Another potential explanation for the link between stronger regional accent and lower perceptions of trustworthiness is that speakers with stronger regional accent might be perceived as being less intelligent or having a lower social status, which might drive trustworthiness judgments. Evidence supporting this claim stems from a previous study, also conducted in Germany, reporting that people with stronger regional accents are perceived as being less competent, and that especially people with a regional accent from eastern Germany are perceived as having a lower socio-intellectual status (Rakić et al., 2011). Ascribing a lower social status to speaker’s who pronounce words differently than subjective standards prescribe (e.g. influenced by a regional accent) and that regional accents are subjects to stereotypes has also been reported for other languages than German (e.g. Kraus et al., 2019; Shah, 2019).

Gender Effects

Previous research suggests that large sex differences in voice pitch might be one explanation why men are more successful in obtaining leadership positions as compared to women, as voters generally prefer leaders with a lower voice pitch (Klofstad et al., 2012). While our data only supports parts of this claim, we still found differences in effects potentially influenced by a speaker’s gender. As reported above, lower voice pitch was generally preferred in male leaders, but the same was not true for female leaders, as preferences for lower pitched female voices were context dependent and only evident in a wartime context. Further, our participants were generally more likely to vote for men in the wartime scenario, but not in the peacetime scenario, also suggesting a context-dependent gender bias. Focusing on female voices only, they were more likely to be preferred as leaders in a peacetime scenario. These effects might be explained by the fact that male voices were generally perceived as being more dominant (but not more or less trustworthy) as compared to female voices. A potential reason for a context-dependent gender bias in leadership decisions is that voice pitch might signal a speaker’s power, strength and fighting ability (Aung & Puts, 2020). All of these traits might simply be more important in wartime as compared to peacetime scenarios and all of these traits are, on average, much more pronounced in men as compared to women. Hence, while our results somewhat contribute to an understanding of gender bias in leadership roles, a full understanding of this gender bias and how the society can overcome it is yet to be gained.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

We would also like to mention some limitations of the current study that directly translate into implications for future studies. First, as our samples (speakers as well as raters) stem from Germany, all of our data has been collected in a WEIRD country (Henrich et al., 2010). Thus, our results might not be generalizable to different countries or world regions, which should be investigated in future studies. Second, we did not have any information on speaker’s actual dominance, trustworthiness or social status. Thus, we were not able to investigate whether perceptions of dominance and trustworthiness based on people’s voices are accurate and if voice pitch is indeed an honest signal of social status (as suggested by Aung & Puts 2020). In the same manner, we did not have any information about the rater’s own regional accent or accents they were exposed to while growing up, which likely influence listener’s perceptions of trustworthiness. Third, we did not collect perceptions of social class or competence based on voices. Based on previous studies reporting that (regional) accent might be related to perceptions of social class and competence (e.g. Kraus et al., 2019; Rakić et al., 2011), future studies should investigate whether associations between regional accent and trustworthiness are mediated by perceived social status or competence. Fourth, the fact that the voice recordings we used as stimuli were standardized did not allow us to validly investigate other potential cues that might be important to form impressions about dominance or trustworthiness, such as loudness or speed that might be especially relevant in social situations (as reviewed in Breil et al., 2021). Fifth, to achieve a full understanding of person perception, visual and auditory perception needs to be integrated. With our study, we were not able to investigate the relative importance of voices in leadership decisions when other cues are available (Rezlescu et al., 2015; Mileva et al., 2018). Future studies could use videos as stimuli to integrate audio and visual modalities. Using real-life interactions would even have a higher ecological validity. Sixth, we used hypothetical voting scenarios and it remains unclear whether our results are generalizable to real-life voting decisions, which might also be an interesting research question for future studies.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a growing literature showing the importance of voices for social perceptions. Our results suggest that voice pitch is related to dominance perceptions, whereas regional accent explains a large amount of variance of trustworthiness perceptions. Further, people form preferences about who they prefer as a leader only based on people’s voices, but leadership decisions are context-dependent and change across wartime vs. peacetime scenarios. A speaker’s gender is another important variable to consider in leadership decisions from voices. Lower voice pitch is beneficial when it comes to votes, but for women only on wartime scenarios. Women are more likely to be voted for in peacetime scenarios as compared to wartime scenarios. Future studies may shed more light on underlying mechanisms that influence how people’s voices contribute to achieving social status and which vocal cues besides voice pitch and regional accent are important.

Data Availability

Open data, analysis script and supplementary material are available via: https://osf.io/ztwm4/.

Notes

In our study leadership decisions refer to the self-reported likelihood of voting for a given candidate/speaker.

Please note that we accidentally preregistered an expected positive association between voice pitch and dominance ratings. This was an honest mistake as, consistent with previous findings, people with lower voice pitch should be perceived as being more dominant, not the other way round.

We also preregistered to model a random slope for context (peacetime vs. wartime) varying in each voice. However, we had to drop this slope in all models, as modelling it led to serious non-convergence warnings, that were not manageable via other approaches (e.g. using optimizers). Importantly, reducing this slope in each model did not change the results. For reasons of transparency, we decided to additionally report the (not converging) preregistered models in the supplementary material.

References

Anderson, R. C., & Klofstad, C. A. (2012). Preference for leaders with masculine voices holds in the case of feminine leadership roles. PloS One, 7, e51216. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051216

Anderson, C., Kraus, M. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Keltner, D. (2012). The local-ladder effect: Social status and subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 23, 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611434537

Anderson, C., John, O. P., Keltner, D., & Kring, A. M. (2001). Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.116

Arslan, R. C., & Tata, C. (2019). Chain simple forms / surveys into longer runs using the power of R to generate pretty feedback and complex designs https://formr.org.Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3229668

Arslan, R. C., Walther, M. P., & Tata, C. S. (2019). formr: A study framework allowing for automated feedback generation and complex longitudinal experience-sampling studies using R. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01236-y

Aung, T., & Puts, D. (2020). Voice pitch: a window into the communication of social power. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.028

Baus, C., McAleer, P., Marcoux, K., Belin, P., & Costa, A. (2019). Forming social impressions from voices in native and foreign languages. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36518-6

Belin, P., Bestelmeyer, P. E. G., Latinus, M., & Watson, R. (2011). Understanding Voice Perception. British Journal of Psychology, 102(4), 711–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02041.x

Breil, S. M., Osterholz, S., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2021). Contributions of nonverbal cues to the accurate judgment of personality traits. In T. D. Letzring, & J. S. Spain (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of accurate personality judgment (pp. 195–218). Oxford University Press

Cartei, V., Bond, R., & Reby, D. (2014). What makes a voice masculine: Physiological and acoustical correlates of women’s ratings of men’s vocal masculinity. Hormones and Behavior, 66(4), 569–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.08.006

Ferguson, H. S., Owen, A., Hahn, A. C., Torrance, J., DeBruine, L. M., & Jones, B. C. (2019). Context-specific effects of facial dominance and trustworthiness on hypothetical leadership decisions. Plos One, 14, e0214261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214261

Feinberg, D. R., & Cook, O. (2020). VoiceLab: Automated Reproducible Acoustic Analysis. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/v5uxf

Fruhen, L. S., Watkins, C. D., & Jones, B. C. (2015). Perceptions of facial dominance, trustworthiness and attractiveness predict managerial pay awards in experimental tasks. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(6), 1005–1016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.07.001

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466, 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/466029a

Hodges-Simeon, C. R., Gaulin, S. J., & Puts, D. A. (2010). Different vocal parameters predict perceptions of dominance and attractiveness. Human Nature, 21, 406–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-010-9101-5

Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.169

Jaeger, B., & Jones, A. L. (2022). Which Facial Features Are Central in Impression Formation? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(2), 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211034979

Lenz, G. S., & Lawson, C. (2011). Looking the part: Television leads less informed citizens to vote based on candidates’ appearance. American Journal of Political Science, 55, 574–589. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00511.x

Little, A. C., Burriss, R. P., Jones, B. C., & Roberts, S. C. (2007). Facial appearance affects voting decisions. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.09.002

Little, A. C., Roberts, S. C., Jones, B. C., & DeBruine, L. M. (2012). The perception of attractiveness and trustworthiness in male faces affects hypothetical voting decisions differently in wartime and peacetime scenarios. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65, 2018–2032. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2012.677048

Lukaszewski, A. W., Simmons, Z. L., Anderson, C., & Roney, J. R. (2016). The role of physical formidability in human social status allocation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 385. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000042

McAleer, P., Todorov, A., & Belin, P. (2014a). How Do You Say ‘Hello’? Personality Impressions from Brief Novel Voices. PLOS ONE, 9(3), e90779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090779

Kempe, V., Puts, D. A., & Cárdenas, R. A. (2013). Masculine men articulate less clearly. Human Nature, 24(4), 461–475

Kinzler, K. D., Corriveau, K. H., & Harris, P. L. (2011). Children’s selective trust in native-accented speakers. Developmental Science, 14(1), 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00965.x

Klofstad, C. A., Anderson, R. C., & Peters, S. (2012). Sounds like a winner: voice pitch influences perception of leadership capacity in both men and women. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279, 2698–2704. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0311

Kraus, M. W., Torrez, B., Park, J. W., & Ghayebi, F. (2019). Evidence for the reproduction of social class in brief speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(46), 22998–23003. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900500116

Mayew, W. J., Parsons, C. A., & Venkatachalam, M. (2013). Voice pitch and the labor market success of male chief executive officers. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.03.001

McAleer, P., Todorov, A., & Belin, P. (2014b). How Do You Say ‘Hello’? Personality Impressions from Brief Novel Voices. PLOS ONE, 9(3), e90779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090779

Mileva, M., Tompkinson, J., Watt, D., & Burton, A. M. (2018). Audiovisual integration in social evaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 44, 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000439

O’Connor, J. J. M., & Barclay, P. (2017). The influence of voice pitch on perceptions of trustworthiness across social contexts. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(4), 506–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.03.001

Oosterhof, N. N., & Todorov, A. (2008). The functional basis of face evaluation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(32), 11087–11092. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805664105

Platow, M. J., Foddy, M., Yamagishi, T., Lim, L., & Chow, A. (2012). Two experimental tests of trust in in-group strangers: The moderating role of common knowledge of group membership. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.852

Puts, D. A., Apicella, C. L., & Cárdenas, R. A. (2012). Masculine voices signal men’s threat potential in forager and industrial societies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279, 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.0829

Puts, D. A., Gaulin, S. J., & Verdolini, K. (2006). Dominance and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in human voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 283–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.11.003

Rakić, T., Steffens, M. C., & Mummendey, A. (2011). When it matters how you pronounce it: The influence of regional accents on job interview outcome. British Journal of Psychology, 102, 868–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02051.x

Rezlescu, C., Penton, T., Walsh, V., Tsujimura, H., Scott, S. K., & Banissy, M. J. (2015). Dominant voices and attractive faces: The contribution of visual and auditory information to integrated person impressions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 39(4), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-015-0214-8

Ryan, E. B., & Bulik, C. M. (1982). Evaluations of Middle Class and Lower Class Speakers of Standard American and German-Accented English. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 1(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X8200100104

Schild, C., Aung, T., Kordsmeyer, T. L., Cardenas, R. A., Puts, D. A., & Penke, L. (2020). Linking human male vocal parameters to perceptions, body morphology, strength and hormonal profiles in contexts of sexual selection. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 21296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77940-z

Schild, C., Stern, J., & Zettler, I. (2019). Linking men’s voice pitch to actual and perceived trustworthiness across domains. Behavioral Ecology, arz173. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arz173

Shah, A. P. (2019). Why are certain accents judged the way they are? Decoding qualitative patterns of accent bias. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 10, 128–139. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.10n.3p.128

Spisak, B. R., Dekker, P. H., Krüger, M., & Van Vugt, M. (2012a). Warriors and peacekeepers: Testing a biosocial implicit leadership hypothesis of intergroup relations using masculine and feminine faces. PloS One, 7, e30399. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030399

Shiramizu, V. K. M., Lee, A. J., Altenburg, D., Feinberg, D. R., & Jones, B. C. (2022). The role of valence, dominance, and pitch in social perceptions of artificial intelligence (AI) conversational agents’ voices. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ea3cq

Spisak, B. R., Homan, A. C., Grabo, A., & Van Vugt, M. (2012b). Facing the situation: Testing a biosocial contingency model of leadership in intergroup relations using masculine and feminine faces. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.08.006

Stern, J., Schild, C., Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., Hahn, A., Puts, D. A., & Arslan, R. C. (2021). Do voices carry valid information about a speaker’s personality? Journal of Research in Personality, 92, 104092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104092

Szakay, A. (2012). Voice quality as a marker of ethnicity in New Zealand: From acoustics to perception1. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 16(3), 382–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2012.00537.x

Thomas, E. R., & Reaser, J. (2004). Delimiting perceptual cues used for the ethnic labeling of African American and European American voices. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 8(1), 54–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2004.00251.x

Torre, I., Goslin, J., White, L., & Zanatto, D. (2018). Trust in artificial voices: A „congruency effect“ of first impressions and behavioural experience. Proceedings of the Technology, Mind, and Society, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3183654.3183691

Tigue, C. C., Borak, D. J., O’Connor, J. J., Schandl, C., & Feinberg, D. R. (2012). Voice pitch influences voting behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.09.004

Van Vugt, M., & Grabo, A. E. (2015). The many faces of leadership: An evolutionary-psychology approach. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415601971

Van Vugt, M., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2008). Leadership, followership, and evolution: some lessons from the past. American Psychologist, 63, 182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.182

Vermue, M., Seger, C. R., & Sanfey, A. G. (2018). Group-based biases influence learning about individual trustworthiness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 77, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.04.005

Von Rueden, C., Gurven, M., & Kaplan, H. (2011). Why do men seek status? Fitness payoffs to dominance and prestige. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 278, 2223–2232. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.2145

Zäske, R., Skuk, V. G., Golle, J., & Schweinberger, S. R. (2019). The Jena Speaker Set (JESS)—A database of voice stimuli from unfamiliar young and old adult speakers. Behavior Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01296-0

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schild, C., Braunsdorf, E., Steffens, K. et al. Gender and Context-Specific Effects of Vocal Dominance and Trustworthiness on Leadership Decisions. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 8, 538–556 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-022-00194-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-022-00194-8