Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this work is to evaluate secukinumab vs. placebo in a challenging-to-treat and smaller US patient subpopulation of the international FUTURE 2–5 studies in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

Methods

Data were pooled from US patients enrolled in the phase 3 FUTURE 2–5 studies (NCT01752634, NCT01989468, NCT02294227, and NCT02404350). Patients received secukinumab 300 or 150 mg with subcutaneous loading dose, secukinumab 150 mg without subcutaneous loading dose, or placebo. Categorical efficacy and health-related quality-of-life (QoL) outcomes and safety were evaluated at week 16. Subgroup analyses were performed based on tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) status and body mass index (BMI). For hypothesis generation, odds ratios (ORs) for American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20/50/70 and Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75/90/100 responses by treatment were estimated using logistic regression without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

Of 2148 international patients originally randomized, 279 US patients were included in this pooled analysis. Mean BMI was > 30 kg/m2 and 55.2% had prior TNFi treatment. ORs for ACR20/50/70 significantly favored patients receiving secukinumab 300 mg and 150 mg with loading dose vs. placebo (P < 0.05), but not those receiving secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose vs. placebo. For PASI75, ORs favored all secukinumab groups over placebo (P < 0.05); for PASI90 and PASI100, only the secukinumab 300-mg group was significantly favored over placebo (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

In this challenging sub-population of US patients with PsA, secukinumab provided rapid improvements in disease activity and QoL. Patients with PsA and active psoriasis might benefit more from secukinumab 300 mg than 150 mg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

In the international, phase 3 FUTURE 2–5 trials of secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA), US patients were a minority of the total population and had baseline disease characteristics indicating harder-to-treat disease, including higher body weight, higher tender and swollen joint counts, and greater likelihood of enthesitis, dactylitis, and prior exposure to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. |

The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of secukinumab in the challenging-to-treat US subpopulation of patients with PsA using pooled data from the FUTURE 2–5 studies. |

What was learned from the study? |

US patients with PsA who received secukinumab had greater improvements in clinical endpoints and quality-of-life measures at week 16 than patients who received placebo and had a similar safety profile to that observed for the full FUTURE 2–5 population; patients who received secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg with a loading dose had the highest clinical response rates. |

Secukinumab treatment was effective in US patients with PsA, who had clinical characteristics indicating a more challenging-to-treat population. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that is characterized by peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, skin and nail psoriasis, and axial disease [1]. PsA is a progressive disease that can lead to irreversible joint damage if not treated early and appropriately [2, 3]. Additionally, PsA is associated with reduced quality of life, physical function, and work productivity [4]. In the United States, the estimated prevalence of PsA in the general population is reported to be in the range of 0.06–0.25% [5]. The prevalence of PsA is higher in people with psoriasis; of the 3.2% (95% CI 2.6–3.7%) of US adults who have psoriasis [6], 19.0% (95% CI 16.3–21.8%) also have PsA [7].

Interleukin (IL)-17A is a proinflammatory cytokine that is key to multiple biological processes characteristic of PsA, including inflammation of joints, enthesitis, cartilage and bone erosion, and pathological new bone growth [8,9,10]. Secukinumab, a selective inhibitor of interleukin 17A, demonstrated rapid and significant improvement in the signs and symptoms of PsA and had a favorable safety profile in the global phase 3 FUTURE studies (FUTURE 1–5) [11,12,13,14,15]. Patients treated with secukinumab achieved significantly higher response rates than those treated with placebo in various efficacy outcomes—including 20, 50, and 70% improvement per American College of Rheumatology (ACR20/50/70) criteria and 75, 90, and 100% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI75/90/100) responses—and experienced significant improvements in quality-of-life measures. Secukinumab has shown significant efficacy across each of the disease manifestations that characterize PsA, including joint and skin symptoms [16, 17]. Furthermore, secukinumab has demonstrated sustained efficacy and safety through 5 years and sustained inhibition of radiographic structural progression through 2 years [18,19,20]. The efficacy of secukinumab has also been demonstrated in both biologic-naive patients and those who have been treated previously with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) but had inadequate response or stopped treatment for safety or tolerability reasons (TNF-IR) [11,12,13,14,15].

US patients were a minority of the total population in the pivotal phase 3 FUTURE trials. These patients had baseline disease characteristics different than those of the global population, and the impact of these differences on treatment response is unknown. A preliminary analysis of the international FUTURE trials found that US patients tended to have characteristics indicating harder-to-treat disease: US patients were heavier; had higher tender and swollen joint counts; and were more likely to have enthesitis, dactylitis, and prior exposure to TNFis than patients from the rest of the world [21]. The objective of this study was to evaluate secukinumab in the US patient subpopulation of the FUTURE studies and report pooled efficacy and safety findings for secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg (with and without loading dose) vs. placebo in this challenging-to-treat population.

Methods

Study Design

Data from the US patients enrolled in FUTURE 2 (NCT01752634), FUTURE 3 (NCT01989468), FUTURE 4 (NCT02294227), and FUTURE 5 (NCT02404350) were pooled and included in this descriptive, hypothesis-generating analysis (Supplementary Material: Fig. S1). FUTURE 1 (NCT01392326) was excluded because the intravenous loading dose is not US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or European Commission (EC) approved for the treatment of PsA. Details of the FUTURE 2–5 studies have been previously described [12,13,14,15]. Briefly, eligible patients were ≥ 18 years old, met the ClASsification criteria for Psoriatic ARthritis (CASPAR), and had active disease with ≥ 3 tender joints and ≥ 3 swollen joints despite treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, and/or corticosteroids.

Patients were randomized to secukinumab 300 or 150 mg with subcutaneous loading dose, secukinumab 150 mg with no loading dose, or placebo. At randomization, patients were stratified on the basis of previous TNFi therapy as TNFi naive or TNF-IR. Patients randomized to secukinumab with loading dose received secukinumab at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 and every 4 weeks thereafter. For the secukinumab regimen without loading dose (in FUTURE 4 and 5), secukinumab 150 mg was administered at baseline, followed by placebo at weeks 1, 2, and 3; secukinumab 150 mg was then administered every 4 weeks starting at week 4.

The primary studies were done in accordance with the principles delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent before study-related procedures. All included studies were approved by each central institutional review board (IRB; FUTURE 2 approving board: Copernicus Group IRB; date of approval, January 17, 2013; Copernicus IRB tracking number: NOV2 12 439; FUTURE 3 approving board: Quorum IRB; date of approval, February 4, 2014; FUTURE 4 approving board: Chesapeake IRB; date of approval, December 12, 2014; FUTURE 5 approving board: Chesapeake IRB; date of approval, June 11, 2015). Approval was also obtained from the ethics review boards of each additional center that participated in the individual studies.

Outcome Measures

Efficacy was assessed by binary response measures at week 16. Improvement in joint symptoms was assessed by ACR20 (the primary efficacy endpoint in the FUTURE studies), ACR50, and ACR70 response rates. Skin symptoms (among patients with ≥ 3% body surface area affected at baseline) were assessed by PASI75, PASI90, and PASI100 response rates. Response for nail symptoms (among those with nail symptoms at baseline) was defined by ≥ 75% improvement in the modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI75) [22]. Additional binary responses were resolution of the swollen joint count of 76 joints (SJC76), the tender joint count of 78 joints (TJC78), enthesitis based on the Leeds Enthesitis Index, and dactylitis based on the Leeds Dactylitis Index [23]. Health-related quality-of-life responses were defined by the minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) in the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI; MCID ≥ 0.35) [24], the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Score (SF-36 PCS; MCID ≥ 2.5) [25], and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Mental Component Score (SF-36 MCS; MCID ≥ 2.5) [25]. To evaluate response using rigorous treatment targets, achievement of Minimal Disease Activity (MDA) thresholds across all MDA components was assessed [26]. MDA components included the achievement of TJC ≤ 1, SJC ≤ 1, tender or swollen enthesitis sites ≤ 1, HAQ-DI ≤ 0.5, PsA pain ≤ 15, patient global assessment of disease activity ≤ 20, and PASI ≤ 1 or body surface area ≤ 3%, each among patients not fulfilling the respective criteria at baseline. Radiographic progression was assessed using available data from week 24 among US patients in FUTURE 5. The proportion of US patients experiencing no structural progression, defined as change in van der Heijde modified total Sharp score (vdH-mTSS) ≤ 0, and mean change from baseline in vdH-mTSS were assessed at week 24. Safety was assessed by evaluation of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analyses

Response rates for binary outcomes were calculated using nonresponder imputation. Nominal P values were calculated for comparisons between treatments for hypothesis generation; no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. Subgroups based on TNFi status (TNFi naive vs. TNF-IR) and body mass index (BMI; ≤ 30 vs. > 30 kg/m2) were also analyzed.

Logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the odds ratios between secukinumab treatments and placebo for achieving binary efficacy responses (ACR20/50/70 and PASI75/90/100), without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Missing data were imputed by nonresponder imputation. The analyses used treatment, baseline BMI, Disease Activity Score 28-joint count using C-reactive protein, Disease Activity Score 28-joint count using erythrocyte sedimentation rate, SJC76, TJC78, and TNFi status (TNFi naive vs. TNF-IR) as explanatory variables.

Results

Patients

Overall, 2148 international patients were originally randomized in the 4 phase 3 studies. A total of 279 US patients (13.0%) were included in this pooled analysis. The patients from FUTURE 2 who received treatment with secukinumab 75 mg were not included, as it is not an FDA- or EC-approved dose for adults.

Baseline characteristics for the US cohort were generally similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Of US patients, 55.6% were women and 55.2% had been previously treated with TNFis. The mean time since diagnosis was 7.0 years. The mean body weight and BMI of US patients included in this study (92.0 kg and 32.3 kg/m2, respectively) were higher than that of non-US patients from FUTURE 2–5 (83.5 kg and 29.1 kg/m2) and indicated an obese population on average (Supplementary Material: Table S1). Enthesitis was present in 69.9% of US patients and dactylitis was present in 38.7%, both of which were slightly higher than the rates in non-US patients (61.5 and 35.4%, respectively). Mean TJC78 was 25.2 and mean SJC76 was 13.7, both higher than in non-US patients (20.6 and 10.5, respectively). US patients more frequently had previous TNFi exposure and less frequently used concomitant methotrexate at baseline than non-US patients.

Efficacy

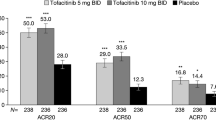

At week 16, ACR20 response rates in US patients were significantly higher with secukinumab 300 mg (59.7% [P < 0.0001]) and secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose (43.4% [P < 0.0001]) than placebo (15.6%) (Fig. 1). Response rates with secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose were numerically higher than with placebo but did not achieve significance (23.5% [P = 0.30]). Responses with secukinumab were seen as early as week 2. ACR50 and ACR70 responses in US patients were also higher with any dose of secukinumab than with placebo. Likewise, a larger proportion of patients who received secukinumab than those treated with placebo had a 100% reduction in TJCs and SJCs and resolution of enthesitis and dactylitis (Table 2).

The week 16 PASI response rates in US patients were higher with secukinumab than with placebo, more so with secukinumab 300 mg than either secukinumab 150 mg regimen (Fig. 2a). At week 16, PASI90/100 response rates were 47.1%/23.5% with secukinumab 300 mg, 22.2%/11.1% with secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose, and 18.2%/9.1% with secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose vs. 5.3%/2.6% with placebo. Secukinumab also led to benefits in other disease domains of PsA (Table 2). A larger proportion of patients treated with secukinumab than placebo experienced improved nail disease: rates of mNAPSI75 were 36.4, 24.6, and 15.0% in the groups receiving secukinumab 300, 150, and 150 mg without loading dose, respectively, vs. 9.1% in the placebo group. Greater rates of improvements in health-related quality of life at week 16 were observed in US patients treated with secukinumab vs. placebo (Fig. 2b). Higher proportions of patients treated with secukinumab achieved MCIDs in HAQ-DI, SF-36 PCS, and SF-36 MCS scores than patients receiving placebo. Similar results were observed when evaluating treatment response across individual MDA components (Supplementary Material: Fig. S2). Overall, secukinumab 300 mg tended to lead to higher response rates than secukinumab 150 mg. For most outcomes, higher response rates were associated with secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose than with secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose.

Achievement of A PASI75, PASI90, and PASI100 and B improvements ≥ MCID in health-related quality-of-life measures in US patients through week 16. HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index, LD loading dose, MCID minimal clinically important difference, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, SEC secukinumab, SF-36 MCS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Mental Component. Score; SF-36 PCS, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey Physical Component Score. *P < 0.05 vs. placebo

Subgroup Analyses

Among the US patients who were TNFi naive, all three secukinumab dose groups had significantly higher response rates vs. placebo for ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 (Fig. 3). TNF-IR patients generally had lower response rates than those who were TNFi naive, although the groups receiving secukinumab 300 mg and 150 mg with loading dose still had significantly higher response rates than the placebo group for ACR20 and ACR50.

In patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2, the ACR20, ACR50, and ACR70 response rates were numerically higher in the secukinumab 300-mg than both secukinumab 150-mg dose groups (Fig. 3). Among patients with BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2, the response rates in the group receiving secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose were notably lower than those in the groups receiving secukinumab 300 mg and 150 mg with loading dose. Comparison between the two BMI subgroups showed no clear trends.

Logistic Regression Analyses of ACR and PASI Response Rates

For all of the ACR binary outcomes, the logistic regression analysis of responses in the US cohort found that the odds ratios significantly (P < 0.05) favored the groups receiving secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose over placebo (Fig. 4). The odds ratios for the groups receiving secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose vs. placebo were > 1 but were not significant.

Odds ratios (95% CI) of secukinumab vs. placebo for ACR and PASI response rates from baseline to week 16 in the US population from a logistic regression model with treatment as a factor and BMI, Disease Activity Score 28-joint count using C-reactive protein, Disease Activity Score 28-joint count using erythrocyte sedimentation rate, SJC76, TJC78, and TNFi status (naive vs. inadequate response) as covariates (nonresponder imputation). ACR American College of Rheumatology, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, LD loading dose, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PBO placebo, SEC secukinumab, SJC76 swollen joint count of 76 joints, TJC78 tender joint count of 78 joints, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor. Error bars indicate 95% CI

For the PASI75 outcomes, the logistic regression analysis found that the odds ratios significantly (P < 0.05) favored all three secukinumab groups over placebo (Fig. 4). For the PASI90 and PASI100 outcomes, only the secukinumab 300-mg group was significantly (P < 0.05) favored over placebo (Fig. 4).

Radiographic Progression at Week 24

Radiographic progression among US patients was assessed using available data collected at week 24 in FUTURE 5 (Supplementary Material: Fig. S3). No trend was observed among treatment groups for the proportion of patients with no structural progression at week 24, defined as vdH-mTSS ≤ 0. However, patients in all three secukinumab groups experienced lower mean (SD) change from baseline in vdH-mTSS at week 24 (300 mg, – 0.01 [0.84]; 150 mg with loading dose, – 0.05 [1.19]; 150 mg without loading dose, – 0.28 [0.81]) compared with placebo (0.66 [2.20]).

Safety Through Week 16

The frequency of all treatment-emergent AEs through week 16 was similar for patients receiving secukinumab 300 mg (51.4%), secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose (54.2%), secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose (55.9%), and placebo (64.4%). The most frequent treatment-emergent AEs in the groups receiving secukinumab 300 mg, secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose, secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose, and placebo, respectively, were upper respiratory tract infection (5.6, 9.6, 8.8, and 10.0%), nasopharyngitis (1.4, 2.4, 8.8, and 7.8%), nausea (1.4, 7.2, 0, and 6.7%), and sinusitis (2.8, 6.0, 2.9, and 2.2%) (Supplementary Material: Table S2). No cases of inflammatory bowel disease, uveitis, major adverse cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, or tuberculosis were observed. Treatment-emergent AEs only led to discontinuation in one instance: an AE of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the groups receiving secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose.

Serious AEs were reported in one patient in the secukinumab 300-mg group (n = 1 each of dehydration, traumatic amputation of the limb, and osteomyelitis); four patients in the secukinumab 150-mg group (n = 1 each of spontaneous abortion, biliary dyskinesia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, coronary artery disease, ectopic pregnancy, gastritis, and suicidal ideation); three patients in the placebo group (n = 1 each of cellulitis, Escherichia urinary tract infection, and infectious mononucleosis). Safety in this cohort appeared similar to that observed in the full study population.

Discussion

Secukinumab was efficacious in US patients with PsA in the pooled FUTURE 2–5 studies, leading to rapid improvements in clinical endpoints and quality-of-life measures. US patients constituted a minority of the FUTURE 2–5 trials, and the demographic and baseline disease-state parameters of US patients indicated that this was a challenging-to-treat subgroup relative to the total population of the FUTURE 2–5 studies [12,13,14,15, 21] and relative to the international population in the recently published EXCEED trial of secukinumab in PsA [26]. Mean TJC78 and SJC76 were 25.2 and 13.7, respectively, which were higher than the range of means reported in the international populations of the FUTURE 2–5 and EXCEED studies (TJC78, 20.0–22.6; SJC76, 9.7–11.7) [12,13,14,15, 26]. Prior TNFi use was also higher in the US patients: only 44.8% were TNFi naive vs. 64.8–76.2% in the full FUTURE 2–5 studies [12,13,14,15]. The mean weight of the US patients was higher than the international populations of the FUTURE 2–5 and EXCEED studies (92.0 vs. 83.4–87.1 kg) [12,13,14,15, 27], and pharmacokinetic studies of secukinumab have shown that its clearance is proportional to a patient’s weight [28], potentially reducing efficacy in heavier patients. The outcomes of treatment with biologics in PsA (and psoriasis and other spondyloarthropathies) have generally been worse in obese patients [29, 30], so the higher mean BMI of the US patients in the present study relative to that of the international FUTURE 2–5 study population again suggested a challenging-to-treat population. More women than men were included in the pooled US patient population (55.6 vs. 44.4%). There is some evidence that women are less likely to respond to biologic treatment for PsA than men [31, 32]. Concomitant methotrexate use was lower in the pooled US patient population compared with the international populations of the FUTURE 2–5 studies (29.7 vs. 46.6–50.1%) [12,13,14,15].

This analysis found that there were numerical differences in responses to the three dosing regimens among the US population, including in the achievement of MDA components. In general, US patients treated with secukinumab 300 mg and secukinumab 150 mg with loading dose achieved the highest response rates, including ACR50 and ACR70 responses and the proportions of patients showing at least an MCID improvement in the health-related quality-of-life measure HAQ-DI. The responses to secukinumab observed in the US patients in this analysis, particularly those who received secukinumab 300 mg or 150 mg with loading dose, were largely similar to the responses observed for the total FUTURE 2–5 population [12,13,14,15]. Considering that treatment with secukinumab 150 mg with and without a loading dose produced similar ACR20/50/70 responses, resolution of enthesitis and dactylitis, and improvements in HAQ-DI in the total FUTURE 4 population [14], the lower efficacy observed with secukinumab 150 mg without loading dose in US patients may be explained partially by higher mean BMI at baseline and slightly higher disease activity at baseline vs. non-US patients. The similar ACR20/50 responses between patients who received 150 mg secukinumab without a loading dose and those receiving placebo are also likely due to the low ACR response rates in patients who were TNFi inadequate responders (Fig. 3). Therefore, a secukinumab loading dose may be particularly important for patients with disease characteristics indicating challenging-to-treat PsA, such as higher body weight, higher tender and swollen joint counts, the presence of dactylitis or enthesitis, and previous TNFi exposure. Radiographic progression among US patients at week 24 as determined by mean change in vdH-mTSS was similar to that observed in the overall population of FUTURE 5, with patients receiving secukinumab experiencing less change from baseline compared with patients receiving placebo [15]. Overall, efficacy and safety results from this analysis are consistent with primary results from the recent CHOICE study, a phase 3 trial evaluating secukinumab in a biologic-naive population of US patients with PsA [33]. These results demonstrate that secukinumab was effective for the treatment of PsA in US patients with clinical characteristics indicating harder-to-treat disease and suggest that other patient populations with similar characteristics (such as high levels of obesity or prior TNFi exposure) would also benefit from treatment with secukinumab.

The TNFi subgroup analysis, which was compatible with previous findings from the global FUTURE 5 population [15], showed that ACR response rates were generally higher at week 16 in TNFi-naive patients than in TNF-IR patients, suggesting that secukinumab is effective as first-line biologic therapy in the US population. In the present study, despite being a more challenging-to-treat population, the proportion of TNFi-naive patients in the secukinumab 300-mg dose group who achieved ACR20 at week 16 was comparable to that in the EXCEED study, which used the same dosing in TNFi-naive patients (63.3 vs. 66%) [27]. The BMI subgroup analysis was equivocal, which may have been due to the relatively small subgroup sizes combined with the fact that patients were not stratified on the basis of weight or BMI at randomization. In the CHOICE study by comparison, secukinumab resulted in similar achievement of ACR responses in patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 or BMI ≤ 30 kg/m2, with numerically greater ACR50/70 responses among patients in the lower BMI subgroup [33].

Our logistic regression analysis of the US cohort at week 16 suggested that using secukinumab with a loading dose may be important to ensure optimal efficacy, regardless of BMI, baseline disease state, or TNFi status. The regression analysis also suggested that again, regardless of BMI, baseline disease state, or TNFi status, patients with PsA plus skin symptoms might benefit more from secukinumab 300 mg than from secukinumab 150 mg. US healthcare providers should be aware that patients may require a loading-dose regimen to achieve optimal treatment outcomes and lower associated long-term healthcare costs.

This study had the limitations inherent to post hoc analyses. Logistic regression analyses were performed without adjustment for multiple comparisons, and nominal P values were calculated for hypothesis generation. In addition, some of the subgroups analyzed were quite small (n < 20). Interpretation of the effect of BMI was limited by the fact that patients were not stratified on the basis of weight or BMI at randomization. Therefore, caution should be exercised in drawing conclusions from these subgroup analyses. The description of US patients in this analysis as challenging-to-treat was intended as a comparison to the total FUTURE 2–5 population and is not intended to refer to any specific definitions or criteria for PsA. Radiographic progression data were only collected in FUTURE 5, and the earliest time of analysis was week 24. Additionally, while patients in all three secukinumab groups experienced lower mean changes from baseline in vdH-mTSS at week 24 vs. placebo, there was variability in these scores within each group. As such, these radiographic findings should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

These results provide valuable insight into the efficacy and safety of secukinumab in a subgroup of US patients with PsA in the FUTURE 2–5 trials who were heavier and had clinical characteristics that indicated more challenging-to-treat disease compared with patients from the rest of the world. Our findings are consistent with those from previous studies and show that secukinumab is an effective treatment for this challenging subpopulation of patients with PsA, with a safety profile similar in US patients to that observed in the full study population. These results suggest that other patient populations who have disease characteristics indicating harder-to-treat disease (such as obesity, higher tender and swollen joint counts, the presence of dactylitis or enthesitis, or previous TNFi exposure) may also benefit from secukinumab and that patients with PsA, particularly those with active psoriasis, may benefit more from secukinumab 300 vs. 150 mg. This analysis also suggests that a loading-dose regimen—particularly for patients receiving secukinumab 150 mg—increases the odds of optimal outcomes in US patients with PsA treated with secukinumab.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–71.

Kane D, Stafford L, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. A prospective, clinical and radiological study of early psoriatic arthritis: an early synovitis clinic experience. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(12):1460–8.

Haroon M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1045–50.

Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(1):91–102.

Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41(4):545–68.

Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):512–6.

Alinaghi F, Calov M, Kristensen LE, et al. Prevalence of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and clinical studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):251-265.e19.

Menon B, Gullick NJ, Walter GJ, et al. Interleukin-17+CD8+ T cells are enriched in the joints of patients with psoriatic arthritis and correlate with disease activity and joint damage progression. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(5):1272–81.

Raychaudhuri SP, Raychaudhuri SK, Genovese MC. IL-17 receptor and its functional significance in psoriatic arthritis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;359(1–2):419–29.

Blauvelt A, Chiricozzi A. The immunologic role of IL-17 in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;55(3):379–90.

Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1329–39.

McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–46.

Nash P, Mease PJ, McInnes IB, et al. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab administration by autoinjector in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (FUTURE 3). Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):47.

Kivitz AJ, Nash P, Tahir H, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous secukinumab 150 mg with or without loading regimen in psoriatic arthritis: results from the FUTURE 4 study. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(3):393–407.

Mease P, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. Secukinumab improves active psoriatic arthritis symptoms and inhibits radiographic progression: primary results from the randomised, double-blind, phase III FUTURE 5 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(6):890–7.

Baraliakos X, Coates LC, Gossec L, et al. Secukinumab improves axial manifestations in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to NSAIDs: primary analysis of the MAXIMISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:195–6.

Orbai AM, McInnes IB, Coates LC, et al. Effect of secukinumab on the different GRAPPA-OMERACT core domains in psoriatic arthritis: a pooled analysis of 2049 patients. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(6):854–64.

Mease PJ, Kavanaugh A, Reimold A, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvements in the signs and symptoms in psoriatic arthritis: final 5 year efficacy and safety results from a phase 3 trial [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 9).

Mease PJ, Landewe RBM, Rahman P, et al. Subcutaneous secukinumab 300mg and 150mg provides sustained inhibition of radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis over 2 years: results from the phase 3 FUTURE-5 trial [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:A262.

Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Reimold AM, et al. Secukinumab for long-term treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a two-year follow up from a phase III, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69(3):347–55.

Kivitz A, Kremer J, Legerton C, et al. Efficacy of secukinumab in a US patient population with psoriatic arthritis: a subgroup analysis of the phase 3 FUTURE studies [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10).

Cassell SE, Bieber JD, Rich P, et al. The modified nail psoriasis severity index: validation of an instrument to assess psoriatic nail involvement in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):123–9.

Mease PJ. Measures of psoriatic arthritis: tender and swollen joint assessment, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI), modified Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (mNAPSI), Mander/Newcastle Enthesitis Index (MEI), Leeds Enthesitis Index (LEI), Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC), Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesis Score (MASES), Leeds Dactylitis Index (LDI), patient global for psoriatic arthritis, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Psoriatic Arthritis Quality of Life (PsAQOL), Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria (PsARC), Psoriatic Arthritis Joint Activity Index (PsAJAI), Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA), and Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (CPDAI). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S64–85.

Mease PJ, Woolley JM, Bitman B, Wang BC, Globe DR, Singh A. Minimally important difference of Health Assessment Questionnaire in psoriatic arthritis: relating thresholds of improvement in functional ability to patient-rated importance and satisfaction. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(11):2461–5.

Strand V, Singh JA. Improved health-related quality of life with effective disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(4):234–54.

Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):48–53.

McInnes IB, Behrens F, Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (EXCEED): a double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1496–505.

Bruin G, Loesche C, Nyirady J, Sander O. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of secukinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(7):876–85.

Edson-Heredia E, Sterling KL, Alatorre CI, et al. Heterogeneity of response to biologic treatment: perspective for psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(1):18–23.

Toussirot E. The interrelations between biological and targeted synthetic agents used in inflammatory joint diseases, and obesity or body composition. Metabolites. 2020;10(3):107.

Højgaard P, Ballegaard C, Cordtz R, et al. Gender differences in biologic treatment outcomes-a study of 1750 patients with psoriatic arthritis using Danish Health Care Registers. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(9):1651–60.

Druyts E, Palmer JB, Balijepalli C, et al. Treatment modifying factors of biologics for psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-regression. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(4):681–8.

Nguyen T, Churchill M, Levin R, et al. Secukinumab in United States biologic-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from the randomized, placebo-controlled CHOICE Study. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(8):894–902.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance.

Medical writing support was provided by Amos Race, PhD, of ArticulateScience LLC, Hamilton, NJ, and Richard Karpowicz, PhD, CMPP, of Nucleus Global, an Inizio company, Hamilton, NJ, USA, and was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. This manuscript was developed in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines. Authors had full control of the content and made the final decision on all aspects of this publication.

Authorship.

All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This work was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA. Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript and funding for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was provided by Novartis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Alan J. Kivitz, Joel M. Kremer, Clarence W. Legerton III, Luminita Pricop, and Atul Singhal contributed to the design of this study, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Alan J. Kivitz has received consultancy fees from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Flexion, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Sun Pharma; has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Celgene, Flexion, Genzyme, GSK, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and UCB; and has stock ownership in Amgen, Gilead, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Joel. M. Kremer is a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech, Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi and has received research grants from AbbVie, Genentech, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer. Clarence W. Legerton III has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, CorEvitas, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GSK, Horizon, Janssen, Scipher, and UCB. Luminita Pricop is an employee and stockholder of Novartis. Atul Singhal has received research/clinical trial grants from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Fujifilm, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Mallinckrodt, MedImmune, Nichi-Iko, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB and has participated in a speakers bureau for AbbVie.

Ethical Approval

The primary studies were done in accordance with the principles delineated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients provided written informed consent before study-related procedures. All included studies were approved by each central institutional review board. Approval was also obtained from the ethics review boards of each additional center that participated in the individual studies.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: A portion of these results were previously presented at the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting; November 8–13, 2019; Atlanta, GA; (Poster 1497).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kivitz, A.J., Kremer, J.M., Legerton, C.W. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Secukinumab in US Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: A Subgroup Analysis of the Phase 3 FUTURE Studies. Rheumatol Ther 11, 675–689 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00666-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-024-00666-1