Abstract

Introduction

Within the EULAR recommendations, patient education (PE) is stated as the basis of the management of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). However, educational needs are scarcely qualitatively studied in axSpA. Therefore, we aimed to explore experiences and needs of PE in patients with axSpA.

Methods

A phenomenological approach was used, with semi-structured in-depth interviews with patients with axSpA including broad variation in characteristics. Thematic analysis was applied. To enhance credibility, data saturation, research triangulation, peer debriefing, member checking, theoretical notes, and bracketing were performed.

Results

Three interrelated themes regarding PE were identified from 20 interviews: illness perception, content, and ‘availability’. Illness perception affects how patients experience and process PE, which consequently influences coping strategies. Prognosis, treatment, and coaching to self-management were identified as the most important content of PE. Regarding ‘availability’, face-to-face PE is preferred for exploring needs, supplemented by self-education, which can be freely applied. Additionally, sufficient time and a comprehensible amount of information were important and participants emphasized the need for axSpA-tailored information for relatives and friends. Participants reported a trusting patient–healthcare provider (HCP) relationship, and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs as prerequisites for effective PE.

Conclusions

This first qualitative study exploring patients’ experiences and needs of PE in axSpA revealed that prognosis, treatment, and coaching to self-management are important regarding content, and the combination of face-to-face contact and self-education the preferred modalities. It seems essential that patients’ illness perceptions are taken into account for effective PE. These results add relevant insights for future PE guidelines in axSpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Educational needs were qualitatively studied in a bottom-up approach in patients with axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). |

For effective patient education (PE) it is essential that patients’ illness perceptions are taken into account. |

Patients with axSpA address prognosis, treatment, and coaching to self-management as the most important PE topics. |

In patients with axSpA, a trusting patient–healthcare provider (HCP) relationship and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs are prerequisites for effective PE. |

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease with heterogeneous manifestations generally developing before the age of 40. Primarily, the sacroiliac joint and spine are affected, but also peripheral manifestations such as arthritis, enthesitis, and dactylitis may occur. Additionally, patients may suffer from extra skeletal manifestations such as uveitis, psoriasis, and IBD. Pain, stiffness, and fatigue have a large impact on daily activities and health-related quality of life (QoL) [1]. These symptoms are the most common motivational factors for seeking medical care and are therefore important drivers of healthcare costs [2, 3]. Patient education (PE) is an important aspect in the guidance of patients with axSpA aiming to maintain QoL. PE not only transfers knowledge but also provides patients with the means to make beneficial decisions, which enables them to play an active role in the management of their disease and improve coping strategies, which may reduce the demand for healthcare resources [4,5,6,7].

PE encompasses all educational activities meliorating patients’ health status and self-management including aspects of therapeutic education, health education, and health promotion [6,7,8]. PE is defined as “the process by which healthcare providers (HCPs) and others impart information to patients that will alter their health behaviors or improve their health status” [9]. There are different modalities of PE available, including verbal communication, written brochures, videos, podcasts, lectures, discussions, digital applications, or a combination thereof [10]. Despite the availability of these modalities, there are barriers on both the HCP’s and the patient’s side that make it hard to deliver PE effectively. The HCP’s attitude and competences, such as knowledge, communication skills, and the ability to assess the educational needs of patients, may influence the quality of PE [11, 12]. Also, the patient’s social and cultural background and physiological factors may influence how PE is received [13]. In addition, the level of health literacy, which helps patients in accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying information about healthcare is of great importance [13, 14].

Within the EULAR recommendations PE is stated as the basis of axSpA management because it contributes to reaching treatment goals [6, 7]. However, educational needs are still scarcely studied in axSpA [6, 7]. A recent questionnaire-based study in patients with axSpA showed that there are individual needs regarding PE depending on gender and age [15]. Another mixed-method study revealed that there is a need for PE in the areas of self-management, feelings and disease process [16]. Nevertheless, patients with axSpA included in these studies had long disease duration and were of older age. Therefore, the transferability of the current evidence and recommendations is limited.

To our knowledge, the experiences and needs of PE in patients with axSpA have not been explored bottom-up using a qualitative research design. Moreover, the World Health Organization advocates incorporation of qualitative research into the development of guidelines and recommendations [17] because it generates rich and detailed data providing explanations and understanding of the complexity of human behavior and decision-making [18, 19].

Methods

We aimed to explore experiences and needs of PE in patients with axSpA using a qualitative research design. An interpretive phenomenological approach was applied to develop a deeper understanding of the perspectives of patients with axSpA regarding PE [20]. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for this study was obtained from the local ethics committees of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) and the Medical Center Leeuwarden (MCL), TPO365,604. All participants provided written informed consent. For reporting, the COREQ checklist was used [Supplementary Material].

Researcher Characteristics

At the time of this study, the interviewers (EV, NL and YK) were senior medical students trained by one of the senior researchers (DP), with expertise in performing qualitative studies and research on PE which was useful for the in-depth quality of the interviews and methods of the study. This senior researcher and the interviewers of the research team (DP, EV, NL and YK) were not involved in the hospital care of the participants and were not acquainted with the participants prior to the study. The other senior researcher of our research team (AS) is a rheumatologist with clinical and research expertise in axSpA; which was useful for the interpretation of the interviews.

Participants

Between March 2020 and November 2022, participants from the Groningen Leeuwarden Axial Spondyloarthritis (GLAS) cohort were recruited from a secondary and tertiary referral center. The GLAS cohort is an ongoing prospective long-term cohort study in patients with axSpA [21, 22]. The purposeful recruitment of patients with a broad variation in characteristics receiving usual care was conducted by screening medical files, and consultation of the GLAS nurse practitioners aiming to include 5 to 25 patients, based on a recommendation for phenomenological studies [20] (Table 1). Selected patients received written and verbal information. Participation was requested and written informed consent was obtained.

Patient and public involvement: Patients or members of the public were not directly involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Data Collection

Data were collected by semi-structured in-depth interviews. Based on the theory of health literacy [14], a theoretical framework was created by the interviewers (EV, NL and YK). This theoretical framework was discussed and adapted within the research team (AS, DP, EV, NL and YK), and subsequently used to develop the interview guide [Supplementary Material]. The interview guide was tested in a pilot interview with the first participant. During the interviews, the conversation followed a narrative structure of the chronology of the participant’s disease experiences. Open-ended questions concerning PE were used and probes were formulated to acquire more in-depth information. Each interview was conducted by one of the interviewers and planned for 60 min. Additionally, peer-debriefing was applied from the start of the interviews; the interviewers discussed their experiences, impressions, and findings between interviews with a clinically experienced researcher (DP), until saturation of information was agreed to be reached [25]. Data saturation was defined as the point at which no additional themes and subthemes emerged from the data [26].

Data Analysis

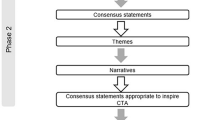

The data collection and analysis were conducted in an iterative manner. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Subsequently, the transcripts were analyzed in Atlas-ti 7.5.7 [27], applying a thematic analysis to translate statements into themes [28]. All interviewers independently coded each transcript. The transcripts were coded in an inductive (data-driven) and deductive (theory-driven) manner [29]. Preliminary analyses and consensus meetings took place after three, eight, 12, 15, and 20 interviews in order to review the codes created so far. Codes were rephrased, merged, and deleted until consensus about the codebook was reached. Corresponding codes with a similar implication were categorized into themes and subthemes to provide an overview of participants’ perspectives on PE. The quotes of the participants have been translated from Dutch to English by the researchers for this manuscript.

Trustworthiness

Multiple strategies were used to enhance credibility [30, 31]. First, the interviewers familiarized themselves with the data and documented the theoretical and reflective thoughts on the subject by designing a theoretical framework. The interviewers discussed their own views on PE regarding axSpA to enhance awareness of feelings and prejudices. Data of the pilot interview were included and used for bracketing and reflexivity. After each interview, the interview guide was discussed with the intention of improving it by including important findings that were further explored in subsequent interviews. Each research team meeting and peer debriefing was documented. Researcher triangulation was conducted. To verify the results and interpretations, member checking was conducted in which the interview transcript and a summary of the results were discussed with the participants. Throughout the study, theoretical notes were kept to ensure continuous reflexivity on the theoretical framework, interview guide, and data analysis.

Results

All 20 approached patients participated in the study (Table 1). Five participants were interviewed at the UMCG, three participants at the MCL, eight participants at home, one participant at work, and the three interviews took place by videocall due to COVID-19-related restrictions. No non-participants were present at the interview. After 15 interviews, data saturation was reached and five more interviews were conducted to verify that no new information emerged.

Theme 1: Illness Perception

Participants emphasized the importance of understanding the origins of their symptoms (illness perception) (Table 2; theme 1). For example, before diagnosis, a participant experienced symptoms of leg and back pain (illness stimuli), which she thought was fibromyalgia. This illustrates a cognitive illness representation. Participants indicated that discussing and seeking confirmation of their illness perceptions or experiences which they believe are related to their disease during PE provides them comfort and knowledge. They also mentioned that it helps them to readjust their illness perceptions and put it into perspective. However, participants also mentioned feeling restraint in addressing the need to discuss their illness perceptions, experiencing the clinical setting as uninviting. They felt that the HCPs are often under time pressure, are preoccupied with administration tasks, and do not pay sufficient attention to illness perception.

Furthermore, participants mentioned various emotional illness representations. For example, a participant reported experiencing overwhelming emotions after a significant life event (illness stimulus). This emotional state influenced the participant’s perception of his illness (axSpA), with the emotional illness representation (feeling sick, defeated, and down) taking precedence. The participant emphasized that he was not yet ready to receive PE, due to feeling overwhelmed with emotions. Another participant mentioned receiving information from a HCP suggesting the possibility of eventually ending up in a wheelchair. It seems that the information given by the HCP (illness stimulus) shaped the illness perception of the participant for the future. This was followed by preparing adjustments to his house (coping strategy) for potential wheelchair use (cognitive illness representation), showing that coping, as a result of an illness perception, may have a major impact on patients’ lives. The illness perception process is constantly influenced by new illness stimuli, and is therefore dynamic and changes over time.

Theme 2: Participants’ Needs Regarding Content

Many participants emphasized different needs regarding relevant topics for PE. The topics, prognosis, treatment, and coaching to self-management were mentioned as important in PE for patients with axSpA (Table 2; theme 2).

After a generally long, uncertain period preceding the diagnosis of axSpA, most of the participants underlined that they are in need of a clearer vision of what to expect in the short and long term. Participants reported that the prognosis of the disease can be very diverse and they balance between hope for improvement and fear of deterioration. Most participants related that by creating more clarity about their personal prognosis, they are better able to reduce uncertainty and anxiety.

Participants highly valued information on treatment. In their experience, treatment is focused on pharmacological therapy. Some participants reported that they would like to participate more in making decisions about medication. On the other hand, other participants explained not feeling empowered enough to make an informed decision or to engage in discussion. For example, they reported that the information given is too much to process all at once to be effectively involved in the decision-making process.

Participants emphasized the need for coaching to self-management. They reported that not much information was given by the HCPs about lifestyle aspects other than physical activity. Participants are particularly interested in PE about possible disease-modifying nutrition, influence of bodyweight, and how to cope with fatigue. In respect of physical activity, participants mentioned that through PE they are made aware of its importance. Nonetheless, they are still in need of more practical guidance, such as how to incorporate physical activity into their daily lives and examples of exercises and/or recommendations on where to go for exercise support. However, simply providing more information about lifestyle seems not enough to integrate this into their lives since participants also reported beliefs and barriers concerning physical activity that prevents them from exercising, which could be addressed in PE to assist in their behavioral change. For instance, some participants believed that they need more motivation and support to expand the amount of physical activity. Three participants who received physical therapy in an axSpA exercise group emphasize that contact with other patients provides extra motivation to increase physical exercise and emotional support in sharing experiences. However, there were also some participants who reported not preferring group therapy/education because they do not want to socialize with other patients with axSpA. Participants also experienced barriers which discourage or prevent them from physical exercise, such as the time-consuming nature and intensity of rehabilitation programs.

Furthermore, in respect to coaching to self-management, participants mentioned that they experience difficulties in maintaining a balance between physical load, mental load, and taking rest. Moreover, they mention struggling to cope with fatigue. Participants had to find a new balance in their energy level and consequently had to prioritize daily activities.

Besides the three topics described above, participants also expressed the need for information on symptoms, axSpA-related diseases, disease influence on daily life, and developments in research.

Theme 3: ‘Availability’ of PE

Participants reported receiving PE through various modalities at different moments in time. They stressed the need for balance in the amount of information given in order to process and understand PE, and highlighted the need for axSpA tailored information for relatives and friends (Table 2; theme 3). They received PE according to the following modalities: face-to-face, telephone call, flyer, symposia, website, online patient portal, and video. Most participants emphasized preferring face-to-face PE, due to the interaction with the HCP in which the focus is on personal needs. Participants felt that time is needed to process and understand the given information, which may lead to new questions. They expressed the need for information on self-education to explore these arising new questions. Another advantage of self-education mentioned by participants is flexibility and easy accessibility.

Participants also mentioned the importance of the right information at the right moment. The way in which the diagnosis is communicated has great influence on the emotional state of the patient. For instance, two participants mentioned receiving the diagnosis during a brief telephone call without proper follow-up. The participants were left with many unanswered questions and lacked coaching to meet their needs. Participants also emphasized that their educational needs during PE depend on interpatient variation in disease severity and understanding (part of health literacy). When participants felt uncertain about experienced symptoms, they had a greater need for PE. Furthermore, they expressed the need for HCPs to check whether the PE met their individual needs, and whether it was understood and sufficient.

Also, participants emphasized the importance of taking into account the amount of information delivered, which depends on health literacy and the emotional state of the patient. For instance, some participants expressed a feeling of relief after their diagnosis because their symptoms finally had a cause. Others expressed a feeling of shock, as suddenly they have a chronic disease of which they know nothing about, influencing their daily lives. The participants emphasized that providing PE in manageable pieces, for example first focusing on the participant’s emotional processing and understanding of the diagnosis, improves the quality of PE.

Lastly, participants expressed the need for axSpA-tailored information for their relatives (including children) and friends. They mentioned finding it difficult to properly explain their disease situation to their relatives and friends, especially to children. Having axSpA not only influences the patient but also the people close to them.

Prerequisites for Effective PE

In addition to the three themes, participants stressed that a trusting patient-HCP relationship and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs is essential to secure the effectivity of PE (Table 2; prerequisites PE).

Participants indicated that the relationship with their HCP plays a major role in PE. They stressed the need for trust in the competences of the HCP. Participants reported that the level of trust they experience determines the extent to which they are willing to open up and express their cognitive and emotional needs to the HCP. Participants emphasized that they find it essential that the HCP shows a personal interest, which benefits the patient–HCP relationship. For example, a participant mentioned a positive effect on this relationship after the HCP expressed a personal interest in a for the patient important trip abroad.

Furthermore, participants stressed the importance of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs about diagnostics, treatment, and PE. Especially during the diagnostic process it was mentioned that they have experienced that different HCPs explained symptoms differently, often restricted to their own expertise, which was sometimes conflicting with other HCPs’ explanations. Participants perceived this as confusing and sometimes even frustrating. Therefore, to allow proper multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement, participants advocated for a more patient-tailored holistic approach.

Discussion

In this qualitative study we explored experiences and needs of PE in patients with axSpA. To our knowledge, this is the first bottom-up qualitative study evaluating PE in axSpA. Three interrelated themes were identified as important from patients’ perspectives: illness perception, needs regarding content, and ‘availability’. Beside these themes, participants reported a trusting patient–HCP relationship and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs as prerequisites for effective PE.

Our theme ‘’Illness perception’’ fits Leventhal’s Common Sense Model, including our subthemes: illness stimuli, illness representations, and coping strategies [31]. Illness perception is important because it influences how individual patients experience and process PE. Previous research in axSpA has already shown that negative illness perceptions and evasive coping strategies are associated with worse QoL [32]. Overall, evasive and reappraisal coping strategies are predominant in patients with axSpA [33]. Interestingly, it has also been shown that without specific intervention, illness perceptions and coping strategies remain stable during the first years after axSpA diagnosis [34]. From our findings, it seems that illness stimuli from PE (including unintended stimuli) could influence coping strategies and therefore may have important consequences for the patient’s wellbeing and QoL. This is in line with previous research that shows that coping strategies are associated with patient-reported outcomes [32, 35]. Additionally, patients may have difficulties recording or processing information given (health literacy). Therefore, in clinical practice, the HCP’s awareness of the patient’s illness perception and health literacy is important, and helps to uncover the patient’s individual needs in PE. If necessary, the illness perception can be readjusted into a more positive direction. Consequently, HCP’s awareness of illness perception promotes more patient-tailored PE. Previous research showed that patient-tailored PE has positive effects on self-perceived health and global wellbeing [6, 7, 36, 37]. Also, the second overarching principle of the EULAR recommendations for the generic core competences of HCPs in rheumatology states that patient-tailored care and patient advocacy are fundamental in the care delivered by HCPs [12]. Previous studies in patients with axSpA showed no results on illness perception regarding PE [15, 16]. However, one study found the need for addressing feelings [16].

Regarding the content of PE, we found similar preferences in information about self-management, disease process, treatment, and prognosis [15, 16]. Compared to our study, mean disease duration and the age of participants were higher in these studies [15, 16]. Our qualitative study additionally showed that developments in research is an important aspect of PE.

Concerning the ‘availability’ of PE, participants prefer face-to-face PE, providing a situation in which HCP can offer information and coaching based on the participant’s personal needs. A prerequisite for this modality is a trusting patient–HCP relationship to open up and express their needs [38, 39]. On the other hand, participants may benefit from more problem-based learning. In this active form of PE, patients are individually challenged to apply the information into their daily lives [40]. Our study shows that after face-to-face PE, there is a need for self-education. Literature shows that using a combination of learning strategies leads to more effective PE [10].

Interestingly, most participants perceived their current treatment predominantly as pharmacological therapy, rather than treatment aiming on resilience and/or the ability to cope with chronic symptoms [41, 42]. Therefore, patients’ attitudes towards ownership of their health seems important in how patients perceive PE and to what extent they are able to incorporate PE. Motivational interviewing may help the HCP to attain a more active attitude by the patient [43, 44]. If an active attitude could be established, it also may increase the effectiveness of PE [8, 43, 44].

The results from our study strengthen and provide new insights complementing the 2022 EULAR/ASAS recommendations on PE in axSpA [6]. A strength of our study was that patients were purposefully recruited. In contrast to earlier studies [15, 16], we had a larger number of patients and larger variation in patient age, resulting in a more representative heterogeneous axSpA study population. Furthermore, participants were recruited from a secondary and tertiary referral center, which contributes to the transferability of our study findings. Moreover, due to the methodology of this qualitative study trustworthiness of data was increased by addressing the thematic analysis methodological quality aspects from Nowell et al. [30], ensuring transparency. Data quality was strengthened through research triangulation.

There are a few limitations to consider in our study. Firstly, participants in our study did not receive group education apart from physical therapy in an axSpA-exercise group and none of the participants in our study were affiliated with the Dutch patient association. Therefore, we lack information on PE from these sources. Furthermore, the transferability of the study findings may partly depend on the socio-cultural background [45]. Therefore, patients with axSpA in countries with a different socio-cultural background than the Netherlands, may have different experiences and needs concerning PE.

Conclusions

Our bottom-up qualitative study in patients with axSpA shows that illness perception, specific content topics, and ‘availability’ are important aspects of PE. PE should be patient-tailored and a trusting patient–HCP relationship, and multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary attunement between HCPs will support effective PE. However, our study shows that the implementation of effective patient-tailored education in axSpA patients is still challenging. Therefore, future research should focus on the evaluation of PE strategies incorporating the different aspects revealed from qualitative research with axSpA patients, preferably in collaboration with axSpA patient associations and HCP involved in the care of these patients.

References

Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):73–84.

Elske Van Den Akker-Van Marle M, Chorus AMJ, Vliet Vlieland TPM, Van Den Hout WB. Cost of rheumatic disorders in the Netherlands. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012;26:721–31.

Vilen L, Baldassari ARCL. Socioeconomic burden of pain in rheumatic disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35:26–31.

Newman S, Steed LMK. Self-management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet. 2004;364:1523–38.

Vyas J. Psychological adjustment to chronic disease. Textb Postgrad Psychiatr. 2018;372:1994–1994.

Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:19–34.

Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:954–62.

Bellamy R. An introduction to patient education: theory and pratice. Med Teach. 2004;26:359–65.

Koongstvedt PR. The managed health care handbook. 4th ed. Gaithersburg (MD): Aspen Publishers; 2001.

Friedman AJ, Cosby R, Boyko S, Hatton-Bauer J, Turnbull G. Effective teaching strategies and methods of delivery for patient education: a systematic review and practice guideline recommendations. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:12–21.

Bergsten U, Bergman S, Fridlund B, Arvidsson B. “Delivering knowledge and advice”: Healthcare providers’ experiences of their interaction with patients’ management of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2011;6:1–9.

Edelaar L, Nikiphorou E, Fragoulis GE, Iagnocco A, Haines C, Bakkers M, et al. 2019 EULAR recommendations for the generic core competences of health professionals in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:53–60.

Beagley L. Educating patients: understanding barriers, learning styles, and teaching techniques. J Perianesthesia Nurs. 2011;26:331–7.

Van Der Heide I, Rademakers J, Schipper M, Droomers M, Sorensen K, Uiters E. Health literacy of Dutch adults: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:179.

Cooksey R, Brophy S, Husain MJ, Irvine E, Davies H, Siebert S. The information needs of people living with ankylosing spondylitis: a questionnaire survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:1–8.

Haglund E, Bremander A, Bergman S, Larsson I. Educational needs in patients with spondyloarthritis in Sweden—a mixed-methods study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:1–9.

Downe S, Finlayson KW, Lawrie TA, Lewin SA, Glenton C, Rosenbaum S, et al. Qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) for Guidelines: Paper 1-Using qualitative evidence synthesis to inform guideline scope and develop qualitative findings statements. Heal Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:76.

Kuper A, Reeves S, Levinson W. Qualitative research: an introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337: a288.

Kelly A, Tymms K, Fallon K, Sumpton D, Tugwell P, Tunnicliffe D, et al. Qualitative research in rheumatology: an overview of methods and contributions to practice and policy. J Rheumatol. 2020;48:6–15.

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2017.

Arends S, Brouwer E, van der Veer E, Groen H, Leijsma MK, Houtman PM, et al. Baseline predictors of response and discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocking therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective longitudinal observational cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(3):R94.

van der Meer R, Arends S, Kruidhof S, Bos R, Bootsma H, Wink F, et al. Extraskeletal manifestations in axial spondyloarthritis are associated with worse clinical outcomes despite the use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(2):157–64.

Machado PM, Landewé R, Van Der HD. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): 2018 update of the nomenclature for disease activity states. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1539–40.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics: International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. Montréal; 2012.

McMahon SA, Winch PJ. Systematic debriefing after qualitative encounters: an essential analysis step in applied qualitative research. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3: e000837.

Grady M. Qualitative and action research: a practitioner handbook. Phi Delta Kappa International. 1998.

ATLAS.ti GmbH. atlas.ti.7. Berlin: Cincom Systems, Inc; 1993.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N. Thematic analysis. In: Smith J, editor. Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2015. p. 222–48.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13.

Cameron LD, Leventhal H. The self-regulation of Health and illness behaviour. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2003.

van Lunteren M, Scharloo M, Ez-Zaitouni Z, de Koning A, Landewé R, Fongen C, et al. The impact of illness perceptions and coping on the association between back pain and health outcomes in patients suspected of having axial spondyloarthritis: data from the spondyloarthritis caught early cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2018;70:1829–39.

Peláez-Ballestas I, Boonen A, Vázquez-Mellado J, Reyes-Lagunes I, Hernández-Garduno A, Goycochea MV, et al. Coping strategies for health and daily-life stressors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gout strobe-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:1–7.

Van Lunteren M, Landewé R, Fongen C, Ramonda R, Van Der Heijde D, Van Gaalen FA. Do illness perceptions and coping strategies change over time in patients recently diagnosed with axial spondyloarthritis? J Rheumatol. 2020;47:1752–9.

Carbo MJG, Paap D, Overbeeke LC, Wink F, Bootsma H, Arends S, Spoorenberg A. Higher levels of physical activity are associated with less evasive coping, better physical function and quality of life in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Submitted 2023.

El Miedany Y, Gaafary ME, Arousy NE, Ahmed I, Youssef S, Palmer D. Arthritis education: the integration of patient-reported outcome measures and patient self-management. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:899–904.

Grønning K, Skomsvoll JF, Rannestad T, Steinsbekk A. The effect of an educational programme consisting of group and individual arthritis education for patients with polyarthritis—a randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:113–20.

Pellegrini CA. Trust: the keystone of the patient-physician relationship. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:95–102.

Paap D, Krops LA, Schiphorst Preuper HR, Geertzen JHB, Dijkstra PU, Pool G. Participants’ unspoken thoughts and feelings negatively influence the therapeutic alliance; a qualitative study in a multidisciplinary pain rehabilitation setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(18):5090–100.

Rich SK, Keim RG, Shuler CF. Problem-based learning versus a traditional educational methodology: a comparison of preclinical and clinical periodontics performance. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:649–62.

Eccleston C, Williams ACDC, Stainton RW. Patients’ and professionals’ understandings of the causes of chronic pain: blame, responsibility and identity protection. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:699–709.

Lennox Thompson B, Gage J, Kirk R. Living well with chronic pain: a classical grounded theory. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42:1141–52.

Johnson A, Sandford J. Written and verbal information versus verbal information only for patients being discharged from acute hospital settings to home: systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2005;20:423–9.

Theis SL, Johnson JH. Strategies for teaching patients: a meta-analysis. Clin Nurse Spec. 1995;9(2):100–20.

Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, Calabrese J, Chater A, Chatterjee H, et al. Culture and health. Lancet. 2014;384(9954):1607–39.

van der Kraan YM, Paap D, Lennips N, et al. AB0481 patient’s perspective on patient education in axial spondyloarthritis: a qualitative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:1268.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients who participated in the GLAS cohort and acknowledge Mrs. S. Katerbarg, Mrs. B. Toonder, Mrs. A.A.H. van der Veen-Hebels, Mrs. M. Middelkoop-Boon, and Mrs. E. Markenstein for their help in recruiting participants for the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Author Contributions

Yvonne van der Kraan, Niels Lennips, Else Veenstra, Davy Paap and Anneke Spoorenberg designed the study. Yvonne van der Kraan, Niels Lennips and Else Veenstra conducted the interviews. Initial analysis was carried out by Yvonne van der Kraan, Niels Lennips and Else Veenstra. Yvonne van der Kraan and Davy Paap conducted the main analyses in consultation with Stan Kieskamp and Anneke Spoorenberg. Yvonne van der Kraan wrote the main manuscript text in consultation with Freke Wink, Davy Paap and Anneke Spoorenberg. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Disclosures

Yvonne van der Kraan, Davy Paap, Niels Lennips, Else Veenstra, Freke Wink, Stan Kieskamp and Anneke Spoorenberg have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Approval for this study was obtained from the local ethics committees of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG) and the Medical Center Leeuwarden (MCL), TPO365,604. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. Consent for publication was obtained.

Data Availability

The interviews underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of individuals that participated in the study. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Kraan, Y.M., Paap, D., Lennips, N. et al. Patients’ Needs Concerning Patient Education in Axial Spondyloarthritis: A Qualitative Study. Rheumatol Ther 10, 1349–1368 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00585-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00585-7