Abstract

Introduction

We studied the effect of intravenous (IV)-golimumab on fatigue and the association of fatigue improvement with clinical response post hoc in adults with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in the GO-ALIVE trial.

Methods

Patients were randomized to IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg (N = 105) at week (W) 0, W4, then every 8 W (Q8W) or placebo (N = 103) at W0, W4, W12, crossover to IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg at W16, W20, then Q8W through W52. Fatigue measures included Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) Question #1 (fatigue; 0 [none], 10 [worst]; decrease indicates improvement) and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) vitality subscale (0 [worst], 100 [best]; increase indicates improvement). Minimum clinically important difference is ≥ 1 for BASDAI-fatigue and ≥ 5 for SF-36 vitality. GO-ALIVE primary endpoint was Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society ≥ 20% improvement criteria (ASAS20). Other clinical outcomes assessed included other ASAS responses, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index score. The distribution-based minimally important differences (MIDs) were determined for BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality. The relationship between improvement in fatigue and clinical outcomes was assessed via multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Mean changes in BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality scores were greater with IV-golimumab versus placebo at W16 (− 2.74/8.46 versus − 0.73/2.08, both nominal p ≤ 0.003); by W52 (after crossover), differences between groups narrowed (− 3.18/9.39 versus − 3.07/9.17). BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality MIDs were achieved by greater proportions of IV-golimumab-treated versus placebo-treated patients at W16 (75.2%/71.4% versus 42.7%/35.0%). A one-point/five-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality scores at W16 increased likelihood of achieving ASAS20 (odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]: 3.15 [2.21, 4.50] and 2.10 [1.62, 2.71], respectively) and ASAS40 (3.04 [2.15, 4.28] and 2.24 [1.68, 3.00], respectively) responses at W16; concurrent improvements and clinical response at W52 were consistent. A one-point/five-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality scores at W16 predicted increased likelihood of achieving ASAS20 (1.62 [1.35, 1.95] and 1.52 [1.25, 1.86], respectively) and ASAS40 (1.62 [1.37, 1.92] and 1.44 [1.20, 1.73], respectively) responses at W52.

Conclusions

IV-golimumab provided important and sustained fatigue improvement in patients with AS that positively associated with achieving clinical response.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02186873.

Plain Language Summary

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a type of arthritis that mostly affects the spine. Patients with AS also often have severe fatigue. Intravenous (IV)-golimumab, which blocks the inflammatory action of tumor necrosis factor, is approved to treat AS. We used information from a clinical trial (GO-ALIVE) to determine whether IV-golimumab reduced fatigue in patients with AS, and if fatigue improvement was associated with improvement in other AS symptoms, including spinal pain, ability to function, and inflammation. In the 1-year GO-ALIVE study, patients were assigned to receive either IV-golimumab or placebo. Patients assigned to placebo were switched to IV-golimumab starting at week 16. The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) fatigue question and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) vitality subscale were used to assess fatigue. Improvement in AS symptoms was measured using the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society ≥ 20% and ≥ 40% improvement criteria (ASAS20 and ASAS40). After 16 weeks of treatment, patients treated with IV-golimumab, on average, had statistically significantly greater improvement in both measures of fatigue than patients treated with placebo. At 1 year, after the placebo group had received IV-golimumab starting at week 16, improvement in fatigue was similar between groups. Improvement in fatigue at week 16 increased the likelihood that ASAS20 and ASAS40 would be achieved at week 16. Similar results were observed at 1 year. Additionally, improvement in fatigue at week 16 predicted the likelihood of achieving ASAS20 and ASAS40 at 1 year. Together, these results demonstrate that IV-golimumab provided important, long-term improvement in fatigue in patients with AS that was positively associated with improvement in AS symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Intravenous (IV)-golimumab is a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor approved in the United States to treat adults with active ankylosing spondylitis (AS). |

In the phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled GO-ALIVE study in adults with active AS, IV-golimumab significantly reduced the signs and symptoms of AS in adults compared with placebo through week 16; clinical response was maintained through 1 year. |

Given that AS is frequently associated with severe fatigue, we conducted a comprehensive, post hoc evaluation of the effect of IV-golimumab on fatigue through 1 year among patients in GO-ALIVE, including assessing the relationship between concurrent fatigue improvement and clinical response, and the ability of fatigue improvement to predict clinical response. |

What was learned from the study? |

Mean changes in Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)-fatigue component and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) vitality subscale scores were greater with IV-golimumab versus placebo at week 16 (− 2.74/8.46 versus − 0.73/2.08, both nominal p ≤ 0.003); by week 52, after placebo crossover to IV-golimumab, differences between groups narrowed (− 3.18/9.39 versus − 3.07/9.17). |

A one-point/five-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality scores at week 16 increased the likelihood of concurrent ASAS20 (odds ratios [95% confidence intervals]: 3.15 [2.21, 4.50] and 2.10 [1.62, 2.71], respectively) and ASAS40 responses (3.04 [2.15, 4.28] and 2.24 [1.68, 3.00], respectively), and a one-point/five-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue/SF-36 vitality scores at week 16 predicted increased likelihood of achieving ASAS20 (1.62 [1.35, 1.95] and 1.52 [1.25, 1.86], respectively) and ASAS40 (1.62 [1.37, 1.92] and 1.44 [1.20, 1.73], respectively) responses at week 52. |

IV-golimumab provided important and sustained fatigue improvement in patients with active AS that was positively associated with achievement of a composite measure of clinical response. |

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory arthritis predominantly affecting the spine [1]. In addition to the symptoms of back pain and progressive spinal stiffness, AS is also frequently associated with severe fatigue [1,2,3,4]. Fatigue has also been identified by the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)/Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials (OMERACT) groups as one of the mandatory core domains that should be assessed in AS research, management, and clinical trials [5, 6]. In patients with AS, fatigue is a complex mixture of both physical and mental exhaustion associated with impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and reduced physical function and work productivity [1, 4, 7]. In a global survey of patients with AS receiving tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), mobility, work productivity, and daily activity were significantly more impaired in patients with high versus low levels of fatigue [4]. The pathophysiology of fatigue in AS is not known, although factors such as disease activity, inflammation, pain, stiffness, depressed mood, reduced physical activity, anemia, and disrupted sleep are thought to be underlying factors [1, 8].

Intravenous (IV)-golimumab is a TNFi approved in the United States since October 2017 to treat adults with active AS [9]. IV-golimumab significantly reduced the signs and symptoms of active AS in adults compared with placebo through week 16 [10], and clinical response was maintained through 1 year [11]. IV-golimumab-treated patients with AS also reported sustained improvements in overall HRQoL and productivity through 1 year [12, 13]. We hypothesized that IV-golimumab treatment would result in sustained improvement in patient-reported fatigue in patients with active AS and aimed to explore the associations between improvement in fatigue and other clinical outcomes.

The primary objective of these post hoc analyses was to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the effect of IV-golimumab on fatigue through 1 year among patients with active AS in GO-ALIVE (NCT02186873; the registrational trial for approval of IV-golimumab for AS in the United States). Secondary objectives were to assess the relationship between improvement in fatigue and clinical response at weeks 16 and 52, and to assess whether change in this important outcome at week 16 could predict clinical response at week 52.

Methods

Patients and Trial Design

GO-ALIVE inclusion/exclusion criteria and trial design were previously published [10]. Briefly, GO-ALIVE was a phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adults ≥ 18 years of age diagnosed with AS for ≥ 3 months (defined by the modified New York criteria) [14] with symptoms of active disease (i.e., Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index [BASDAI] score ≥ 4 [15], total back pain visual analog scale [VAS, 0–10 cm] score ≥ 4, and C-reactive protein [CRP] level ≥ 0.3 mg/dL) who had an inadequate response or intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Concomitant use of NSAIDs throughout the study was permitted at stable doses established ≥ 2 weeks prior to the first study drug administration. No more than 20% of the study population could have received prior treatment with one TNFi other than golimumab. Additionally, these patients could not have discontinued the TNFi due to lack of efficacy within the first 16 weeks of treatment and could not have received the TNFi within 3 months of the first study drug administration (except etanercept within 6 weeks). Previous treatment with golimumab, other biologics, or Janus kinase inhibitors was not permitted. Additional inclusion and exclusion details are summarized in the Supplementary Material.

Patients were randomized 1:1 using an interactive Web-response system to receive IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg at weeks 0, 4, 12, then every 8 weeks (Q8W) or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 12 with crossover to IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg at weeks 16 and 20, then Q8W through week 52. Randomization was stratified by geographic region and prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No).

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments and Good Clinical Practices. The protocol was approved by Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board (IRB) for seven sites in Canada (approval number: 201404734) and the United States (approval number: 201404241); the remaining 39 sites received approval from their local IRB or ethics committee (see list in Supplementary Material). All patients gave written informed consent.

Trial Assessments and Outcomes

Available measures of fatigue from GO-ALIVE were the BASDAI question assessing the overall level of fatigue/tiredness in the past week and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) vitality subscale, a general measure of energy/fatigue. Both of these measures have been shown to be appropriate for the assessment of fatigue in patients with AS [1,2,3, 16, 17]. The BASDAI is a patient-reported assessment of AS disease activity with six questions evaluating different disease characteristics [15]. The fatigue question (Question #1) of the BASDAI questionnaire assesses the severity of fatigue using the question, “How would you describe the overall level of fatigue/tiredness you have experienced?” scored on a VAS ranging from 0 (none) to 10 cm (worst). The SF-36 is a patient-reported assessment that evaluates overall HRQoL and is not disease specific [18]. The SF-36 vitality subscale includes four items that assess energy level and fatigue on a scale from 0 (worst score) to 100 (best score). The questions included in the SF-36 vitality subscale are: How much of the time during the past 4 weeks (1) Did you feel full of pep?; (2) Did you have a lot of energy?; (3) Did you feel worn out?; and (4) Did you feel tired? The four scores are averaged together.

Efficacy in GO-ALIVE was assessed using ASAS domains (total back pain [0–10 cm VAS], patient global [0–10 cm VAS], function [Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) score], and inflammation [mean of BASDAI Questions #5 and #6 regarding morning stiffness]) [19, 20], the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) [21,22,23], the BASFI score [24,25,26], the BASDAI [15], and the SF-36 [18]. Predetermined clinical response endpoints assessed in GO-ALIVE utilized in these analyses included ASAS20 (≥ 20% improvement from baseline in at least three of the four ASAS domains with an absolute improvement ≥ 1 [0–10 cm VAS] and an absence of deterioration [≥ 20% worsening and absolute worsening ≥ 1] in the potential remaining domain); ASAS40 (≥ 40% improvement from baseline in three of the four ASAS domains with an absolute improvement ≥ 2 [VAS 0–10 cm] and no worsening in the remaining domain); ASAS 5/6 (≥ 20% improvement from baseline in any five of the following six components: the four ASAS domains, CRP level, and spinal mobility [lumbar side flexion]) [20]; ASAS partial remission (a score ≤ 2 out of ten in each of the ASAS domains) [20]; ASDAS [21,22,23] clinically important improvement (decrease ≥ 1.1), major improvement (decrease ≥ 2.0), and inactive disease (score < 1.3); and ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in BASFI score [24,25,26].

Statistical Methods

The analyses reported here were performed post hoc and included all randomized patients analyzed by assigned treatment group. Descriptive statistics were reported as counts and percentages for dichotomous endpoints and means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous endpoints. For the BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores (continuous endpoints), missing baseline data were replaced with the median value, and last observation carried forward was used for all other missing data. For the binary clinical response endpoints (i.e., ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS inactive disease, and ≥ 20% improvement in BASFI score), patients with missing data were considered nonresponders (nonresponder imputation).

Mean (SD) change from baseline was determined for the BASDAI-fatigue score (at weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 28, 36, 44, and 52) and the SF-36 vitality score (at weeks 8, 16, 28, and 52). The distribution-based minimally important differences (MIDs) for the BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores were defined as one-half the SD of the baseline score [27]. The proportions of patients who achieved the MID for the BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality scores through week 52 and the proportions of patients who achieved the accepted minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the BASDAI-fatigue (improvement ≥ 1; validated as the MCID [28] and used in previous analyses [29]) or SF-36 vitality (improvement ≥ 5; validated as the MCID [18, 30]) scores through week 52 were assessed by treatment group. The proportions of patients achieving clinical response (ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS inactive disease, and ≥ 20% improvement in BASFI score) were determined among patients who did or did not achieve the MIDs for the BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality scores at weeks 16 and 52.

Multivariable logistic regression models were used to evaluate the relationship between clinical response endpoints (dependent variables) and improvement from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue score or SF-36 vitality score (independent variables), after adjustment for baseline ASDAS, prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No), baseline CRP level, and treatment group. The resulting odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimated the fold increase in the odds of achieving a clinical response endpoint at week 16 or 52 with each one-point concurrent improvement in the BASDAI-fatigue score (MCID [28, 29]) or five-point concurrent improvement in the SF-36 vitality score (MCID [18, 30]) at week 16 or 52 among all randomized patients. Multivariable logistic regression models with clinical response endpoints at week 52 as dependent variables and improvement from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue score or SF-36 vitality score at week 16 as independent variables were also conducted.

A Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No) was used to compare the proportions of patients who achieved BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality MIDs by treatment group and to compare clinical responses among patients who did or did not achieve BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality MIDs. Analysis of covariance with factors of treatment group, baseline score, and prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No) was used to compare change from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores between treatment groups. All statistical tests were performed at a two-sided α = 0.05 level, and all p values are nominal.

Results

Patient Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 208 patients were randomized and treated in the GO-ALIVE trial (IV-golimumab N = 105, placebo N = 103) [10]. Detailed patient characteristics and demographics have been previously reported [10]. Overall, 78% of patients were male and the mean age was 39 years. Mean duration since AS diagnosis was 5.5 years, and 12 patients (5.8%) had complete ankylosis of the spine. Fourteen percent of patients had previously received one TNFi (IV-golimumab N = 16; placebo N = 14). The proportion of patients receiving NSAIDs at baseline was comparable between groups (89.5% in the IV-golimumab group and 87.4% in the placebo group). Patients reported substantial fatigue at baseline, with mean ± SD BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores of 7.1 ± 1.5 and 38.4 ± 7.4, respectively, in the IV-golimumab group and 7.2 ± 1.5 and 37.4 ± 8.5, respectively, in the placebo group.

Fatigue Improvement

At the earliest time points evaluated and through week 16, mean improvements from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores were greater in IV-golimumab-treated versus placebo-treated patients (Fig. 1a, b). The mean change from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue score in IV-golimumab-treated versus placebo-treated patients at week 16 was − 2.74 versus − 0.73, respectively (Fig. 1a), and the mean change from baseline in SF-36 vitality score was 8.46 versus 2.08, respectively (Fig. 1b). Following crossover of the placebo group to IV-golimumab at week 16 and through week 52, mean improvements in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores were similar between the treatment groups. At week 52, the mean change from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue score in the IV-golimumab and placebo-crossover groups was − 3.2 and − 3.1, respectively, and the mean change from baseline in SF-36 vitality score was 9.4 and 9.2, respectively.

Mean (SD) change from baseline in the a BASDAI-fatigue score and the b SF-36 vitality score through week 52. Improvement is indicated by a decrease in BASDAI-fatigue score and increase in SF-36 vitality score. Patients randomized to placebo crossed over to IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg at week 16 (dotted line). Missing baseline data were replaced with the median value, and last observation carried forward was used for all other missing data. Nominal p values are based on analysis of covariance with factors of treatment group, baseline score, and prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No). BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, IV intravenous, SD standard deviation, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

The distribution-based MIDs for the BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores were determined to be ≥ 0.73 and ≥ 3.98, respectively. Greater proportions of IV-golimumab-treated versus placebo-treated patients achieved the MIDs for BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores at the earliest time points evaluated and through week 16 (Fig. 2a, b). At week 16, 75.2% of IV-golimumab-treated patients versus 42.7% of placebo-treated patients achieved the BASDAI-fatigue MID, and 71.4% versus 35.0%, respectively, achieved the SF-36 vitality MID. Following placebo crossover and through week 52, the proportions of patients achieving the BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality MIDs were similar between the treatment groups (Fig. 2a, b). At week 52, approximately 80% of IV-golimumab and placebo-crossover patients achieved the MID for the BASDAI-fatigue score, and approximately 70% achieved the MID for the SF-36 vitality score. At all time points evaluated, the proportions of patients who achieved the established BASDAI-fatigue (≥ 1) or SF-36 vitality (≥ 5) score MCIDs were similar to those who achieved the BASDAI-fatigue (≥ 0.73) or SF-36 vitality (≥ 3.98) score MIDs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Proportion of patients who achieved a BASDAI-fatigue score (≥ 0.73) or b SF-36 vitality score (≥ 3.98) MID through week 52. Patients randomized to placebo crossed over to IV-golimumab 2 mg/kg at week 16 (dotted line). Missing baseline data were replaced with the median value, and last observation carried forward was used for all other missing data. Nominal p values are based on Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No). BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, IV intravenous, MID minimally important difference, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Maintenance of fatigue improvement from week 16 to week 52 was also observed in most patients randomized to IV-golimumab. Among IV-golimumab-treated patients who achieved the BASDAI-fatigue MID at week 16, 94.9% maintained the MID at week 52. Among IV-golimumab-treated patients who achieved the SF-36 vitality MID at week 16, 86.7% maintained the MID at week 52.

Relationship Between Fatigue Improvement and Clinical Response

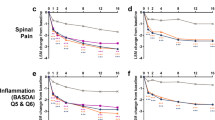

Across all predetermined clinical efficacy endpoints evaluated (i.e., ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS inactive disease, and ≥ 20% improvement in BASFI score), concurrent clinical response rates were greater in patients randomized to IV-golimumab who achieved the BASDAI-fatigue or SF-36 vitality MID compared with those who did not (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S2). For example, 86.1% of patients who achieved the BASDAI-fatigue score MID (≥ 0.73 improvement) at week 16 also achieved an ASAS20 response at week 16 (the GO-ALIVE primary endpoint) (Fig. 3a). In contrast, 34.6% of patients who did not achieve the BASDAI-fatigue MID at week 16 achieved an ASAS20 response at week 16. Similarly, 86.7% of patients who achieved the SF-36 vitality score MID (≥ 3.98 improvement) at week 16 also achieved an ASAS20 response at week 16 versus 40.0% of patients who did not. At week 52, an ASAS20 response was achieved by 83.3% of patients who achieved the BASDAI-fatigue MID at week 52 versus 14.3% of patients who did not, and by 80.0% of patients who achieved the SF-36 vitality MID versus 43.3% of patients who did not (Fig. 3c).

Proportion of patients who achieved an ASAS (a, c) or ASDAS response (b, d) at week 16 or 52 among patients randomized to IV-golimumab who did or did not achieve the BASDAI-fatigue score (≥ 0.73) or SF-36 vitality score (≥ 3.98) MID at week 16 or 52. Missing baseline data were replaced with the median value, and last observation carried forward was used for all other missing data. For week 52, nominal p values are based on a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by prior TNFi therapy (Yes, No). ASAS20 and ASAS40 are defined as ≥ 20% or ≥ 40% improvement, respectively, from baseline in ASAS criteria. ASAS 5/6 is defined as ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in any five of the six ASAS criteria. ASAS partial remission is defined as a score ≤ 2 out of ten in each of four ASAS domains (total back pain, patient’s global, function, and inflammation). ASDAS clinically important improvement and major improvement are defined as a decrease ≥ 1.1 or decrease ≥ 2.0, respectively, in ASDAS. ASDAS inactive disease is defined as an ASDAS score < 1.3. ASAS Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, IV intravenous, MID minimally important difference, SF-36 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Multivariable logistic regression models demonstrated that, among all randomized patients combined, fatigue improvement was determined to be significantly associated with concurrent clinical efficacy response (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Patients with a one-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue or five-point improvement in SF-36 vitality score at week 16 were more likely to achieve an ASAS20 response at week 16 (OR 3.15, 95% CI 2.21, 4.50 and OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.62, 2.71, respectively). Similarly, patients with a one-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue or five-point improvement in SF-36 vitality score at week 52 were more likely to achieve an ASAS20 response at week 52 (OR 2.73, 95% CI 2.06, 3.62 and OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.56, 2.43, respectively). Results were similar across all clinical response endpoints evaluated (ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS inactive disease, and ≥ 20% improvement in BASFI score).

Fatigue improvement at week 16 was also a nominally significant predictor of future clinical response (Table 2). Patients with a one-point improvement in BASDAI-fatigue score at week 16 were more likely to achieve an ASAS20 response at week 52 (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.35, 1.95), and patients with a five-point improvement in SF-36 vitality score at week 16 were more likely to achieve an ASAS20 response at week 52 (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.25, 1.86). Results were similar across all clinical endpoints evaluated except for ≥ 20% improvement in BASFI score, which had a lower nominally nonsignificant OR of association with BASDAI-fatigue (1.07, 95% CI 0.95, 1.20) than the other clinical efficacy endpoints (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

This comprehensive analysis of fatigue in patients with active AS demonstrated that IV-golimumab treatment resulted in early and sustained important improvement of fatigue. Among patients randomized to IV-golimumab, improvement was observed at the earliest time points evaluated (week 2 for BASDAI-fatigue and week 8 for SF-36 vitality), increased through week 16, and was subsequently sustained through week 52. Among patients randomized to placebo, after crossover to IV-golimumab at week 16, mean improvement in fatigue was similar to that observed in the IV-golimumab group by week 20 and was sustained through week 52. These results are consistent with the improvement in fatigue reported with IV-golimumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis [31] and rheumatoid arthritis [32]. Additionally, although comparison would not be appropriate due to differences in study designs, populations, and fatigue assessment tools, subcutaneous golimumab has also been shown to improve fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, or AS [33, 34] and reduce sleep disturbance in patients with AS [35].

The findings reported here derive from patient assessments utilizing the BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality instruments, and previous studies in patients with psoriatic arthritis [31] or rheumatoid arthritis [32] utilized the SF-36 vitality and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue [36] instruments. Although improvement in fatigue with IV-golimumab has been consistently observed regardless of the instrument used, further research studying other assessment tools commonly utilized in clinical settings may also be informative.

At weeks 16 and 52, the majority of IV-golimumab-treated patients (70% to 80%) had achieved the MID (as determined using a distribution-based method) in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores. At week 16, 42.7% of placebo-treated patients achieved the BASDAI-fatigue MID and 35.0% achieved the SF-36 vitality MID. Significant improvement in subjective and objective outcomes in placebo-treated patients is commonly reported in randomized, placebo-controlled trials [37]. Reasons for this placebo response may include psychological placebo effect, high disease severity at baseline, natural history disease fluctuation, and/or regression to the mean phenomenon.

These analyses also demonstrated the relationship between improvement in fatigue and clinical response, supporting the importance of addressing this common yet challenging symptom when managing patients with AS. Improvements in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores at weeks 16 and 52 were significantly associated with concurrent clinical response, as assessed by ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS clinically important improvement, ASDAS major improvement, ASDAS inactive disease, and ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in BASFI score. In addition, fatigue improvement at week 16 predicted clinical response at week 52. It should be noted that although ≥ 20% improvement from baseline in BASFI score is not a validated outcome in patients with AS, it is in line with published minimum clinically important improvement values for this functional measure [24,25,26]. These associations and identification of improvement in fatigue as a significant predictor of future clinical response emphasize the importance of the early assessment and management of fatigue in patients with AS. These results are also consistent with the significant correlation of improvement in disease activity with improvement in fatigue previously reported in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with IV-golimumab [32].

The odds ratios for the associations between BASDAI-fatigue and response were slightly larger than those for the SF-36 vitality score for nearly all clinical response endpoints, and it is important to note that the magnitude of the differences for these measures are not directly comparable. The BASDAI-fatigue score is an AS-specific measure and may be a more sensitive predictor of clinical response in patients with AS compared with the SF-36 vitality score, which is not disease specific. Additionally, the BASDAI-fatigue question assesses only fatigue whereas the SF-36 vitality questions assess both fatigue and energy. Fatigue and energy may not be experienced in exactly the same way, even though they are similar concepts, as one could be interpreted as physical and the other as mental fatigue. For example, lack of energy may not be the same as feeling fatigued, and not feeling fatigued may not be the same as having energy/being energized [7].

The positive associations between concurrent improvements in fatigue and achievement of clinical response support the results of previous studies that demonstrated that fatigue is related to a broad range of the symptoms experienced by patients with AS, including pain and stiffness, as well as impaired sleep quality and HRQoL and reduced physical function [35, 38,39,40,41,42,43]. The low percentages of IV-golimumab-treated patients who did not achieve the BASDAI-fatigue (0%) or SF-36 vitality (6.7–13.3%) MID among patients who achieved ASAS partial remission or ASDAS inactive disease at weeks 16 and 52 support the association of fatigue with these symptoms. The relatively substantial proportions of patients who did not achieve the BASDAI-fatigue (14.3–53.8%) or SF-36 vitality (40.0–56.7%) MID among patients who achieved less stringent measures of clinical response (i.e., ASAS20 and ASDAS clinically important improvement) demonstrate that fatigue associated with AS is multidimensional and, in some patients, fatigue improvement may be influenced by different factors than those that affect clinical response, such as pain, sleep, work, disease activity, anemia, functional ability, global well-being, and mental health, as has been previously suggested [1, 2, 7, 16, 44].

The impact of disease duration on improvement in fatigue outcome measures was not assessed in these analyses, which is a limitation of this study. However, impact of disease duration on IV-golimumab efficacy and safety was assessed in a previously published post hoc analysis of data from the GO-ALIVE trial [45]. In this analysis, IV-golimumab improved the signs and symptoms of AS compared with placebo in patients with early (symptom duration of 2 to 3 years) and late (symptom duration of 21 to 24 years) disease, although mean improvements and response rates, including BASDAI, were numerically higher in patients with early disease. These data suggest fatigue improvement may also be greater in patients with early versus late disease. Another limitation of the data presented here is the small number of patients who had previously received a TNFi (N = 30), which precluded assessment of the effect of IV-golimumab on fatigue in TNFi-experienced versus TNFi-naïve patients, potentially reducing the generalizability of the results of this study. It should be noted that patients who discontinued a prior TNFi due to primary lack of response were excluded from GO-ALIVE and the proportions of TNFi-experienced patients were balanced between groups, limiting any potential impact of such patients on analysis findings.

Conclusions

In these post hoc analyses, compared with placebo, IV-golimumab treatment resulted in significantly greater improvements from baseline in BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores as early as week 2 and week 8, respectively, continuing through week 16. Additionally, greater proportions of IV-golimumab-treated versus placebo-treated patients achieved the distribution-based MIDs for the BASDAI-fatigue and SF-36 vitality scores at week 16. Fatigue improvement was sustained through week 52. This improvement in fatigue was associated with concurrent and future improvements in other clinical symptoms and may be predictive of better clinical outcomes. These results demonstrate that IV-golimumab is effective in the management of many symptoms that are important to patients with AS [5, 6].

References

Connolly D, Fitzpatrick C, O’Shea F. Disease activity, occupational participation, and quality of life for individuals with and without severe fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis. Occup Ther Int. 2019. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/oti/2019/3027280/.

Dagfinrud H, Vollestad NK, Loge JH, Kvien TK, Mengshoel AM. Fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comparison with the general population and associations with clinical and self-reported measures. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:5–11.

Haywood KL, Packham JC, Jordan KP. Assessing fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis: the importance of frequency and severity. Rheumatol. 2014;53:552–6.

Strand V, Deodhar A, Alten R, et al. Pain and fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: multinational real-world findings. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27:e446–55.

Landewé R, van Tubergen A. Clinical tools to assess and monitor spondyloarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:47.

Navarro-Compán V, Boel A, Boonen A, et al. The ASAS-OMERACT core domain set for axial spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:1342–9.

Farren W, Goodacre L, Stigant M. Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis: causes, consequences and self-management. Musculoskeletal Care. 2013;11:39–50.

Braun J, van der Heijde D, Doyle KM, et al. Improvement in hemoglobin levels in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1032–6.

Janssen Biotech, Inc. Simponi Aria. Prescribing information. 2021. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/SIMPONI+ARIA-pi.pdf. Accessed 17 May 2023

Deodhar A, Reveille JD, Harrison DD, et al. Safety and efficacy of golimumab administered intravenously in adults with ankylosing spondylitis: results through week 28 of the GO-ALIVE study. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:341–8.

Reveille JD, Deodhar A, Caldron PH, et al. Safety and efficacy of intravenous golimumab in adults with ankylosing spondylitis: results through 1 year of the GO-ALIVE study. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:1277–83.

Reveille JD, Deodhar A, Ince A, et al. Effects of intravenous golimumab on health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: 28-week results of the GO-ALIVE trial. Value Health. 2020;23:1281–5.

Reveille JD, Hwang MC, Danve A, et al. The effect of intravenous golimumab on health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results of the phase 3 GO-ALIVE trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:1331–41.

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8.

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–91.

van Tubergen A, Coenen J, Landewe R, et al. Assessment of fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a psychometric analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:8–16.

Dernis-Labous E, Messow M, Dougados M. Assessment of fatigue in the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1523–8.

Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:3130–9.

Anderson JJ, Baron G, van der Heijde D, Felson DT, Dougados M. Ankylosing spondylitis assessment group preliminary definition of short-term improvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1876–86.

Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The assessment of spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:Suppl:ii1-44.

Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society (ASAS). ASDAS-Calculator. 2019. https://www.asas-group.org/education/asas-app/. Accessed 17 May 2023

Machado P, Landewé R, Lie E, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score (ASDAS): defining cut-off values for disease states and improvement scores. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:47–53.

van der Heijde D, Lie E, Kvien TK, et al. (ASAS) ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1811–8.

Calin A, Garrett S, Whitelock H, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: the development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–5.

Pavy S, Brophy S, Calin A. Establishment of the minimum clinically important difference for the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Indices: a prospective study. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:80–5.

Kviatkovsky MJ, Ramior S, Landewé R, et al. The minimum clinically important improvement and patient-acceptable symptom state in the BASDAI and BASFI for patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1680–6.

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41:582–92.

van Tubergen A, Black PM, Coteur G. Are patient-reported outcome instruments for ankylosing spondylitis fit for purpose for the axial spondyloarthritis patient? A qualitative and psychometric analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1842–51.

Navarro-Compán V, Wei JC, Van den Bosch F, et al. Effect of tofacitinib on pain, fatigue, health-related quality of life and work productivity in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. RMD Open. 2022;8: e002253.

Bjorner JB, Wallenstein GV, Maring MC, et al. Interpreting score differences in the SF-36 vitality scale: using clinical conditions and functional outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:731–9.

Husni ME, Kavanaugh A, Chan EKH, et al. Effects of intravenous golimumab on health-related quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of the GO-VIBRANT trial. Value Health. 2020;23:1286–91.

Bingham CO 3rd, Weinblatt M, Han C, et al. The effect of intravenous golimumab on health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: 24-week results of the phase III GO-FURTHER trial. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1067–76.

Kruger K, Burmester GR, Wassenberg S, Bohl-Bühler M, Thomas MH. Patient-reported outcomes with golimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: non-interventional study GO-NICE in Germany. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:131–40.

Genovese MC, Han C, Keystone EC, et al. Effect of golimumab on patient-reported outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the GO-FORWARD study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1185–91.

Deodhar A, Braun J, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab reduces sleep disturbance in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1266–71.

Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, Gladman DD. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:936–9.

Vollert J, Cook NR, Kaptchuk TJ, Sehra ST, Tobias DK, Hall KT. Assessment of placebo response in objective and subjective outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3: e2013196.

Kvien TK, Conaghan PG, Gossec L, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained reduction in fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: long-term results of two phase III randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022;74:759–67.

Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Tsai W-C, et al. Relationship between disease activity status or clinical response and patient-reported outcomes in patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: 104-week results from the randomized controlled EMBARK study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:4.

Revicki DA, Luo MP, Wordsworth P, Wong RL, Chen J, Davis JC, for the ATLAS Study Group. Adalimumab reduces pain, fatigue, and stiffness in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results from the adalimumab trial evaluating long-term safety and efficacy for ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1346–53.

Aissaoui N, Rostom S, Hakkou J, et al. Fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: prevalence and relationships with disease-specific variables, psychological status, and sleep disturbance. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:2117–24.

Hammoudeh M, Zack DJ, Li W, Stewart VM, Koenig AS. Associations between inflammation, nocturnal back pain and fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis and improvements with etanercept therapy. J Int Med Res. 2013;41:1150–9.

Brophy S, Davies H, Dennis MS, et al. Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis: treatment should focus on pain management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:361–7.

Furst DE, Kay J, Wasko MC, et al. The effect of golimumab on haemoglobin levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52:1845–55.

Deodhar AA, Shiff NJ, Gong C, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous golimumab in ankylosing spondylitis patients with early and late disease through one year of the GO-ALIVE study. J Clin Rheumatol. 2022;28:270–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients who participated in the GO-ALIVE study.

Funding

This work was supported by Janssen Research & Development, LLC. Authors who were employed by Janssen were involved in trial design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, drafted or revised the manuscript, and approved the manuscript for publications. Publication of this article was not contingent upon approval by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. The Rapid Service Fee and the Open Access fee were funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Holly Capasso-Harris, PhD, of Certara Synchrogenix under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298–1304) and was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Study conception and design were performed by Atul Deodhar, Natalie J. Shiff, Cinty Gong, Eric K.H. Chan, Elizabeth C. Hsia, Kim Hung Lo, Alianu Akawung, Lilianne Kim, Stephen Xu, and John D. Reveille. Acquisition, analysis, and/or interpretation of data were performed by Atul Deodhar, Natalie J. Shiff, Cinty Gong, Eric K.H. Chan, Elizabeth C. Hsia, Kim Hung Lo, Alianu Akawung, Lilianne Kim, Stephen Xu, and John D. Reveille.

Disclosures

Atul Deodhar has received consulting fees for participation in advisory boards from AbbVie, Amgen, Aurinia, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; grant/research support from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; speaker/advisory board fees from AbbVie, Aurinia, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; and medical writing support funded by AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Natalie J. Shiff is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; received salary support from the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance within the past 3 years; and owns or has owned stock in AbbVie, Gilead, Iovance, Novo-Nordisc, and Pfizer within the past 3 years. Cinty Gong is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC. Eric K.H. Chan is an employee of Janssen Global Services, LLC, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. Elizabeth C. Hsia, Kim Hung Lo, Aliana Akawung, Lilliane Kim, and Stephen Xu are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, and may own stock in Johnson & Johnson. John D. Reveille has received consulting fees for participation in advisory boards from Eli Lilly and UCB, and research grant funding from Eli Lilly and Janssen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The protocol was approved by Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board (IRB) for 7 sites in Canada (approval number: 201404734) and the United States (approval number: 201404241); the remaining 39 sites received approval from their local IRB or ethics committee. All patients gave written informed consent. The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964.

Data Availability

The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at https://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the trial data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deodhar, A., Shiff, N.J., Gong, C. et al. Effect of Intravenous Golimumab on Fatigue and the Relationship with Clinical Response in Adults with Active Ankylosing Spondylitis in the Phase 3 GO-ALIVE Study. Rheumatol Ther 10, 983–999 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00556-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-023-00556-y