Abstract

Introduction

We sought to identify and compare treatment response groups based on individual patient responses (rather than group mean response) over time on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in patients treated with baricitinib 4-mg in 4 phase 3 studies.

Methods

Trajectory subgroups were identified within each study using growth mixture modeling. Following grouping, baseline characteristics and disease measures were summarized and compared.

Results

In each study, three response trajectories were identified. In the three studies of patients naïve to biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) patients had, on average, high disease activity, as measured by CDAI. In these studies, a group of rapid responders (65–71% of patients) had the lowest baseline CDAI scores and achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 by week 16. Gradual responders (10–17%) had higher baseline CDAI, but generally achieved low disease activity (CDAI ≤ 10) by week 24. A group of partial responders (18–22%) had higher baseline CDAI and did not achieve mean CDAI ≤ 10. In bDMARD-experienced patients, the subgroups were rapid responders, who achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 (42% of patients); partial responders, with mean CDAI decrease of ~ 15 points from baseline (42% of patients); and limited responders (15% of patients). Changes in modified total sharp score (mTSS; assessed only in biologic-naïve patients) were below the smallest detectable difference at 24/52 weeks for > 90% of patients in each group, excepting partial responders in RA-BEGIN (≥ 75% no detectable change).

Conclusion

In patients receiving baricitinib 4-mg, lower baseline CDAI was generally associated with rapid response, while higher baseline CDAI scores were generally seen for patients who either reached treatment targets more gradually, or who had a partial or limited response. Maintenance of response was observed with continued baricitinib treatment in all response groups and generally included maintenance of mTSS.

Plain Language Summary

Baricitinib is an oral agent widely approved for the treatment of moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis). Although baricitinib (and other agents) have demonstrated efficacy at the population level, treatment responses vary considerably between individual patients. This study assessed four baricitinib phase 3 clinical studies and categorized patient responses into response groups based on the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) using a growth mixture model. We then evaluated baseline characteristics and corresponding disease measures within the response groups. In patients with no prior treatment with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), 65–71% of patients had rapid responses to treatment, while smaller groups had gradual (10–17%) or partial (18–22%) responses. In patients with prior bDMARD experience, rapid and partial responders each comprised 42% of patients while 15% had limited response. Gradual responders generally had higher baseline CDAI versus rapid responders, but achieved low disease activity (LDA) by 24, versus 12 weeks for rapid responders. Across response groups, patients who continued treatment generally maintained their response up to 52 weeks, and where joint erosion was assessed (in bDMARD-naïve patients), generally saw maintenance of joints during continued therapy. The identification of a gradual responder group, which demonstrated good response but required more time to achieve LDA, is relatively novel and should be considered when setting treatment expectations, particularly in patients with high baseline disease activity. In addition, in bDMARD-experienced patients, many patients did not achieve LDA but maintained a substantial partial response with continued therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Despite advances in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, many patients do not respond rapidly to therapy. |

We used growth mixture modeling to categorize individual patient treatment responses into response trajectory subgroups during baricitinib clinical studies and then assessed baseline characteristics within the groups. |

What was learned from the study? |

In addition to large rapid responder groups, gradual responder groups were identified in each study comprising patients who achieved LDA targets over longer periods of time. |

These findings may be helpful in informing future discussions around treatment switching. |

Introduction

The continued introduction of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) has improved responses to treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA); nonetheless, response to treatment remains heterogeneous either with conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs) or bDMARDs [1,2,3]. Given the large number of potential interacting factors affecting RA disease development and progression, including genetic, immunomodulatory, psychosocial, and environmental factors, precise prediction of treatment response for various agents is not currently feasible. In addition, much of the literature on treatment response in RA presents mean or median response; however, recent characterizations of the trajectories of individual patient treatment response over time with growth mixture models show that for individual patients, different patterns of response over time may be observed [2, 4]. Major treatment guidelines such as those of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) or the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommend following a treat-to-target approach with the target of remission or low disease activity [5, 6]. In the context of those recommendations, the characterization of treatment response patterns for individual patients could help inform clinical decisions regarding the timing of treatment switches and set appropriate patient expectations for the likely speed and magnitude of therapeutic response.

Baricitinib is an oral selective Janus kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor widely approved for treatment of RA in adults with moderately to severely active disease who have had an inadequate response to 1 or more DMARDs. Baricitinib has been assessed in patients with moderately to severely active RA in phase 3 studies across a range of RA treatment experience from little or no experience with methotrexate (MTX) and no prior bDMARDs, to inadequate response to at least one tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor despite ongoing treatment with cDMARDs [7,8,9,10,11].

The Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) for rheumatoid arthritis is a composite index encompassing swollen and tender joint counts, and patient and investigator assessments of severity. It is more readily accessible relative to the Simple Disease Activity Index in that it does not require measurement of clinical analytes, specifically C-reactive protein. Here we sought to identify, within each of the baricitinib study populations, patient subsets with distinct CDAI response trajectories among individual patients during baricitinib treatment for RA, and to summarize the baseline characteristics associated with those response patterns.

Methods

Due to the differences in prior treatment and disease characteristics between study populations, data were assessed separately within each study. Safety and efficacy results, as well as complete study designs, have been reported previously: RA-BEGIN [9], RA-BEAM [10], RA-BUILD [11], and RA-BEACON [8].

All studies were conducted in accordance with ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The master IRB that approved the protocol for each of the studies was Quorum Review. Ethics approvals were also obtained for all 281 sites for RA-BEAM, all 182 sites for RA-BUILD, all 178 sites for RA-BEACON, and all 198 sites for RA-BEGIN. All patients provided written informed consent before the first study procedure.

Studies and Populations

All studies assessed adult patients ≥ 18 years of age. Patients were required to have at least moderately to severely active RA, generally defined as ≥ 6 of 68 tender joints and ≥ 6 of 66 swollen joints, and meeting study-specific thresholds for a high C-reactive protein concentration (greater than the upper limit of normal [ULN]; greater than 1.2 × ULN; greater than 2 × ULN). Additional details of the inclusion/exclusion criteria have been published previously: RA-BEGIN [9], RA-BEAM [10], RA-BUILD [11], and RA-BEACON [8]. Patients who did not adequately respond to the study drug were eligible for rescue treatment after the primary endpoint of each study.

In RA-BEGIN, patients had limited or no treatment with MTX and were naïve to other DMARDs [9]. Patients could receive baricitinib 4-mg once daily, or baricitinib 4-mg and MTX.

In RA-BEAM, patients had inadequate response to MTX and were naïve to other DMARDs [10]; patients were required to have used MTX for ≥ 12 weeks with a stable dose of 15–25 mg/week for ≥ 8 weeks prior to baseline. A stable dose of MTX was continued throughout the trial. Patients received baricitinib 4-mg once daily, placebo, or adalimumab 40-mg every other week. After 12 weeks of treatment, patients assigned to baricitinib or adalimumab treatment continued to receive their randomly assigned therapy; patients randomized to placebo were switched to baricitinib 4-mg at 24 weeks.

In RA-BUILD, patients had inadequate response or intolerance to at least one cDMARD and no bDMARD experience at study entry [11]. Patients were randomized to receive baricitinib (2-mg [data not shown] or 4-mg once daily) or placebo added to stable background therapy.

In RA-BEACON, patients had previously received at least one TNF inhibitor and discontinued treatment because of insufficient response or intolerance [8]. Patients could receive baricitinib 2-mg (data not shown) or 4-mg once daily in addition to the therapies they were receiving at enrollment.

Statistical Analyses

A growth mixture model, a novel method of latent class mixed model, was applied to classify patients into different subgroups based on Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) response trajectories [2, 12]. Data were analyzed separately by study; analyses were performed using R software. For RA-BEGIN or RA-BEAM, data up to rescue from weeks 0–52 were used; for RA-BUILD or RA-BEACON, data up to rescue from weeks 0–24 were used. For RA-BEGIN, since the baricitinib 4-mg monotherapy and baricitinib 4-mg with MTX arms performed similarly, data were pooled for the purpose of growth mixture modeling. Within each study, trajectories of observed CDAI were modeled into subgroups based on their response patterns, with the optimal number of subgroups determined by a Bayesian information criterion. Following identification of the groups, baseline patient demographics and disease activity measures were summarized by trajectory group. In addition, the proportion of patients with observed modified total Sharp score [mTSS] [13] change from baseline less than the smallest detectable change at week 24 and/or 52 were calculated within each trajectory group. Similarly, health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI), pain visual analog scale (VAS), tender 28-joint count (TJC28), and swollen 28-joint count (SJC28) trajectory overtime were described by trajectory group. Low disease activity for CDAI was defined as ≤ 10 [6, 14].

Results

Treatment Response Trajectory Groups

For the three studies in patients with no prior bDMARD experience (RA-BEGIN, RA-BEAM, and RA-BUILD), response trajectory groups were relatively similar; results are described here in detail for RA-BEAM and provided in tables and figures for the RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD studies. Results for patients with prior TNF experience (RA-BEACON) are described in detail following those for the other studies. In each of the three studies, patients had on average high disease activity at baseline.

RA-BEAM

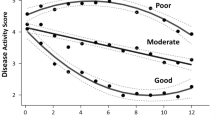

The three CDAI trajectory groups identified for RA-BEAM are shown in Fig. 1, and the proportion of patients within each of the three trajectory groups achieving LDA criteria (CDAI ≤ 10) is shown by time in Fig. 2. Rapid responders (N = 344, 70.6%) had a relatively lower mean baseline CDAI within the high disease activity range (33.8, Table 1), and achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 at approximately 12 weeks. Gradual responders (12% of patients) had a relatively higher mean baseline CDAI of 48.5 and achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 by 24 weeks. The partial responders group (18% of patients), had a mean CDAI at baseline of 48.0 and at 52 weeks of 20.3. In terms of slope (or rate of improvement), relatively rapid improvement was seen in both the rapid and gradual responder groups (Fig. 1), with decreases in CDAI of 19.2 and 17.2 points, respectively, by week 4, versus 12.0 points for the partial responder group (Table 2). By week 12, slope for the rapid responder group was leveling off as a 70% decrease (− 23.7 points) from baseline and mean CDAI had reached the cutoff for LDA. For gradual responders, the early rate of improvement continued past week 12, with a 64.4% improvement (− 31.2 points) at week 12 and an 80% improvement (− 38.8 points) at week 24. For partial responders, some improvements continued, with a 31.4% improvement (− 15.1 points) at 12 weeks and a 46.8% improvement (− 22.5 points) at 24 weeks, which was maintained through 52 weeks (57.7% improvement, − 27.7 points).

When baseline values for some individual components of the CDAI (SJC28 and TJC28) and patient-reported outcomes (pain VAS and HAQ-DI) were compared between responder groups, the pattern was similar to that seen for baseline CDAI scores—lower in the rapid responder group than in the other two trajectory groups. Most other baseline characteristics were relatively comparable across the 3 trajectory groups (Table 1). However, for baseline mTSS scores, the rapid responder and gradual responder groups had similar mean scores (41.0 and 40.6, respectively), while the partial responder group had a somewhat higher (worse) baseline mTSS score of 49.8.

Following treatment with baricitinib 4-mg in RA-BEAM, mTSS was generally preserved, with changes at week 24 less than the smallest discernible change for 95.9% of rapid responders, 91.8% of gradual responders, and 91.8% of partial responders (Table 3). These proportions remained similar at 52 weeks.

As seen for the relationship at baseline, following treatment patterns of change for pain VAS, HAQ-DI, TJC28, and SJC28 were generally similar to those for CDAI within the three trajectory response groups in RA-BEAM (Fig. 3).

Pain VAS, HAQ-DI, TJC28, and SJC28 by trajectory group and study week in RA-BEAM. Individual patient data, gray lines. Mean trajectory for rapid responders, red lines; gradual responders, green lines; partial responders, blue lines. VAS visual analog scale, HAQ-DI health-assessment questionnaire disability index, TJC28 tender 28-joint count, SJC28 sollen 28-joint count

RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD

In studies RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD, three trajectory response groups were identified with patterns similar to the groups identified in RA-BEAM (Fig. 4A, C; Supplemental Fig. 1A and 1B). In these two studies, rapid responders comprised the largest group—65% of patients in RA-BEGIN and 69% of patients in RA-BUILD (Table 1)—and achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 by approximately 8 to 14 weeks. Gradual responders comprised 17% of patients in RA-BEGIN and 10% of patients in RA-BUILD and achieved mean CDAI ≤ 10 at approximately 16 to 24 weeks. Finally, partial responders (18% of patients in RA-BEGIN, 22% of patients in RA-BUILD) showed a sustained decrease in mean CDAI, but did not generally reach or maintain mean CDAI ≤ 10 through 24 (RA-BUILD) or 52 weeks (RA-BEGIN) of therapy (Fig. 4A, C; Supplemental Fig. 1A and 1B). Patterns of rates of change (slope) were generally comparable to those seen in RA-BEAM (Fig. 4).

In RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD, gradual responders had notably higher mean baseline CDAI values compared to the rapid responders (Table 1). As in RA-BEAM, partial responders had mean baseline CDAI scores similar to those of the gradual responder groups. Overall, baseline mTSS was lower in RA-BEGIN (range across groups: 8.1–18.3) and RA-BUILD (15.7–26.3), as compared to that observed in RA-BEAM (40.6–49.8) (Table 1). Baseline mTSS values for RA-BEGIN were relatively similar and lower in the rapid (11.8) and gradual responder groups (8.1) versus the partial responder group (18.3). In contrast, in RA-BUILD baseline mTSS was lowest in the partial responder group (15.7), intermediate in the gradual responder group (22.8), and highest in the rapid responder group (26.3).

Following treatment, mTSS was generally preserved in patients who continued treatment with baricitinib in RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD (Table 3). As in RA-BEAM, patterns of response in RA-BEGIN and RA-BUILD for pain VAS, HAQ-DI, SJC28, and TJC28 were similar to those for CDAI within each of the three patient trajectory groups (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 2A and 2B).

RA-BEACON

In RA-BEACON, which assessed patients who had failure or intolerance to at least one TNF inhibitor, three response groups were identified, although the patterns of response differed somewhat versus the other three studies. Rapid responders, with a pattern similar to the other studies, comprised 42.4% of patients (Table 1; Fig. 4D; Supplemental Fig. 1C). Partial responders (42.4% of patients) comprised the second group; this group showed a substantial decrease in mean CDAI by approximately week 8, which was largely maintained through 24 weeks. However, partial responders did not achieve mean CDAI ≤ 10. Finally, there was a limited response group (15.3%), which showed a limited decrease in CDAI from high baseline levels (mean 54.9) by week 8, and a mean CDAI that remained above 40 through 24 weeks (Fig. 4D). As in the other studies, the pattern of changes during treatment for pain VAS, HAQ-DI, and SJC28 and TJC 28 were similar to that for CDAI across the response groups in RA-BEACON (Supplemental Fig. 2C).

Discussion

In the present analyses, three treatment response trajectory groups were identified within each study. Across the studies of patients who were bDMARD-naïve (RA-BEAM, RA-BEGIN, and RA-BUILD), despite high average baseline disease activity, the majority of patients were rapid responders, achieving CDAI LDA by weeks 12–16. A smaller group of patients were gradual responders; these patients showed a relatively rapid rate of improvement but started from a higher mean CDAI score at baseline versus rapid responders, and achieved mean CDAI LDA by week 24. A small third group of patients in each of these studies were partial responders, who had slower improvements and on average achieved and maintained a reduction in CDAI of approximately 20 points from baseline by week 24. Across these trajectory groups and studies, patients generally saw little progression in structural damage of joints. In patients with prior bDMARD experience (RA-BEACON), who also had high mean baseline disease activity, > 40% of patients receiving baricitinib 4-mg were rapid responders, while a similar proportion were partial responders who had substantial decreases in CDAI but did not achieve LDA. The remaining patients had limited responses. Joint damage was not directly assessed in this population.

The main objective of these analyses was to describe response patterns during baricitinib treatment; however, identifying predictors of each trajectory group would be of interest. As part of the present analyses, attempts to assess predictors of response patterns were made using machining learning approaches (classification and regression tree or random forest) evaluating all potential baselines as well as early responses. In the example of CDAI trajectory groups in this paper, an early improvement in CDAI dominated the prediction relative to baseline characteristics from each study. Specifically, patients who did not achieve LDA by week 12 but who had a reasonable partial response (both the rapid and gradual responder groups achieved a ≥ 50% mean reduction by week 12; see Table 2) were relatively likely to achieve LDA or continued response by week 24/52, and this factor was more strongly associated with response than baseline factors. When evaluating baseline predictors alone, the top baseline predictors of the different response patterns (most often CDAI, SDAI, and/or DAS28) selected using the random forest method varied between the individual studies. Due to this variability, we have not attempted to report baseline predictors, since they were not generalizable. In addition, even for the top baseline predictors, the negative predictive value was still generally low, which further limits the value of such findings for practical use.

Overall, our findings provided three major insights. First, patients might respond to baricitinib 4-mg differently, with a group of patients, often including many patients with the highest baseline disease activity requiring a longer time to achieve LDA; however, all groups of bDMARD-naïve patients benefited from protection against further structural damage (bDMARD-experienced patients were not assessed for structural damage). Secondly, baseline characteristics did not reliably predict response across studies—for example, the gradual response group started with high CDAI and lower mTSS, whereas the partial response group had high CDAI and higher mTSS in BEGIN and BEAM, but that pattern was not repeated in BUILD. Therefore, we have not described baseline predictors of response, since none of the baseline factors was identified using machine learning approaches as strong predictors of subsequent response group across the different studies. Thirdly, an early improvement (by week 12) in CDAI was seen in baricitinib 4-mg responders. In rapid responders, this often resulted in mean LDA, while in gradual responders, who generally had higher baseline CDAI scores, early response predicted a continued improvement to LDA by approximately week 24. These findings suggest that in treatment experienced patients, particularly those with relatively high baseline disease activity who report a symptomatic improvement with a corresponding reduction in CDAI but without attaining LDA by 12 weeks, continuing therapy without switch with reassessment at 24 weeks may be warranted.

The identification in these analyses of a patient trajectory group, which requires a longer time to respond but which does achieve LDA, is an important finding, with potential implications in treatment decisions and in setting expectations for time to LDA response, particularly in patients with more severe disease characteristics at baseline. Notably, the 10–17% of gradual responders among bDMARD-naïve patients achieved marginally lower mean CDAI by the end of treatment relative to the rapid responder group. Therefore, continued therapy was effective in these patients, and consideration should likely be given to the magnitude of baseline disease activity measures when setting expectations for how rapidly LDA cutoffs may be achieved. These findings in gradual responders may help inform considerations about the most appropriate intervals for treatment adjustments when starting or changing drug therapy until the desired treatment target is reached, particularly in patients showing a notable but incomplete early response to treatment [15].

In the present analyses, the least responsive trajectory group, partial (or limited in RA-BEACON) responders, comprised 12–22% of patients in each study. In the studies of bDMARD-naïve patients, the partial responders had a substantial decrease in CDAI from baseline maintained through the end of the treatment period; however, they failed to achieve CDAI LDA. In bDMARD-experienced patients, treatment response in this group through 12 weeks (or longer) was limited. Risk profiling for refractory RA was reported by Bécède and colleagues for a cohort of patients who had failed to achieve LDA after ≥ 3 courses of DMARDs (including ≥ 1 bDMARD) [16]. In that study, higher CDAI was significantly associated with development of refractory disease [16], and consistent with this observation, the limited responder group in RA-BEACON (partial to nonresponders) had the highest CDAI of any group across the studies assessed herein.

The present analysis of response trajectories bears methodological similarities to studies reported by Siemons et al. [4] and by Courvoisier et al. [2] Siemons et al. assessed disease trajectories for DAS28 during a treat-to-target study using MTX and TNF inhibitors in the DREAM remission induction cohort [4]. That study identified three trajectory groups: a large group of rapid responders, a moderate-sized group of slower responders, and a small group of poor responders; thus the response patterns were relatively similar to the present study. Siemons et al. did not report baseline characteristics by response group. Courvoisier et al. assessed DAS28 response in pooled data from nine national RA registries following abatacept initiation [2]. The results of that study also identified three response groups, with a large group of responders who achieved low DAS28 from already relatively low baseline levels, a small group with relatively rapid reductions from higher baseline DAS28 levels, and a small group with more limited response.

Strengths of the present study were that data were prospectively collected with minimal missing information and should have been relatively consistent and reliable since they were obtained in randomized, controlled clinical trials. One limitation may be that data were censored after rescue, resulting in trajectory trends being driven by the patients as observed. In addition, the generalizability of data collected from randomized clinical trials of patients with moderately to severely active and refractory RA to usual practice is unknown.

In summary, in each study, a large group of patients showed rapid improvements in CDAI and in patient-reported measures including HAQ-DI and pain, following baricitinib dosing. In biologic-naïve patients, a group of patients was also identified which achieved LDA targets more gradually, typically from a higher mean baseline CDAI score. In the study of biologic experienced patients, in addition to a rapid responder group, a second group achieved and maintained a mean decrease in CDAI from baseline of approximately 15 points but did not achieve mean LDA; this response pattern was comparable to that in the 3rd trajectory group (‘partial responders’) in the biologic-naïve studies. Further studies may be warranted to determine whether treatment switch or ongoing treatment with a sustained partial response represents the best treatment option in this population. In biologic-naïve patients (where mTSS was assessed), structural damage was generally limited with continued treatment, even in patients with partial but sustained response. Across the studies, more rapid achievement of CDAI LDA was observed in patients with less treatment experience and lower baseline CDAI scores.

Conclusions

The identification in biologic-naïve patients of a trajectory group which typically had high baseline CDAI scores but achieved LDA targets over an extended period of time may be helpful in informing future discussions around treatment switching.

References

Aga AB, Lie E, Uhlig T, et al. Time trends in disease activity, response and remission rates in rheumatoid arthritis during the past decade: results from the NOR-DMARD study 2000–2010. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):381–8.

Courvoisier DS, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Gottenberg JE, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients after initiation of a new biologic agent: trajectories of disease activity in a large multinational cohort study. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:302–6.

Kiely PD. Biologic efficacy optimization–a step towards personalized medicine. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(5):780–8.

Siemons L, Ten Klooster PM, Vonkeman HE, et al. Distinct trajectories of disease activity over the first year in early rheumatoid arthritis patients following a treat-to-target strategy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(4):625–30.

Smolen JS, Landewe RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):685–99.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(1):1–25.

Keystone EC, Taylor PC, Drescher E, et al. Safety and efficacy of baricitinib at 24 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):333–40.

Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1243–52.

Fleischmann R, Schiff M, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):506–17.

Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):652–62.

Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Chen YC, et al. Baricitinib in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs: results from the RA-BUILD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):88–95.

Reinecke J, Seddig D. Growth models in longitudinal research. AStA Adv Stat Anal. 2011;95:415–34.

van der Heijde D. How to read radiographs according to the Sharp/van der Heijde method. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(1):261–3.

Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(4):R796-806.

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3–15.

Becede M, Alasti F, Gessl I, et al. Risk profiling for a refractory course of rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(2):211–7.

Bruynesteyn K, Boers M, Kostense P, et al. Deciding on progression of joint damage in paired films of individual patients: smallest detectable difference or change. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(2):179–82.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work, including open-access fees, was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of the study results and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. PCT, JP, and MW were involved in the study design. EM, ARR, and TH were involved in data collection. TH was involved in medical study monitoring. YC, BJ, LS, and YL were involved in data analyses and plotting. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Medical writing support, under the guidance of the authors, was provided by Elizabeth Flate, PhD, and Thomas Melby, MS, and editorial assistance was provided by Dana Schamberger, MA, all of Syneos Health (Morrisville, NC, USA) and funded by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA) in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines. PCT would like to acknowledge support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

Disclosures

Peter Taylor reports research grants from Celgene and Galapagos; and consultation fees from AbbVie, Biogen, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Nordic Pharma, Fresenius, and UCB. Janet Pope reports consultation and speaking fees from Eli Lilly, as well as being an advisory board member for Eli Lilly. Michael Weinblatt reports research grants from Amgen, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Sanofi; and consultation fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Corrona, Crescendo Bioscience, GlaxoSmithKline, Horizon, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche (which owns Genentech), Scipher, and SetPoint; as well as owning stock in Can-Fite, Inmedix, Scipher, and Vorso. Eduardo Mysler has received honorarium as speaker or participation in advisory boards from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Sanofi, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Roche, Sandoz, and Gemmene. Andrea Rubbert-Roth reports honoraria for lectures and consultation fees from Eli Lilly. Yun-Fei Chen, Bochao Jia, Luna Sun, Yushi Liu, and Thorsten Holzkämper are full-time employees of and own stock in Eli Lilly. Yoshiya Tanaka has received speaking fees and/or honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly, Novartis, YL Biologics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Chugai, AbbVie, Astellas, Pfizer, Sanofi, Asahi Kasei, Glaxo Smith Kline, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Gilead, Janssen, and has received research grants from AbbVie, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Chugai, Asahi Kasei, Eisai, Takeda, and Daiichi Sankyo.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All studies were conducted in accordance with ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee for each center. All patients provided written informed consent before the first study procedure. The master IRB that approved the protocol for each of the studies was Quorum Review. Ethics approvals were also obtained for all 281 sites for RA-BEAM, all 182 sites for RA-BUILD, all 178 sites for RA-BEACON, and all 198 sites for RA-BEGIN.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at http://www.vivli.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, P.C., Chen, YF., Pope, J. et al. Patient Disease Trajectories in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated with Baricitinib 4-mg in Four Phase 3 Clinical Studies. Rheumatol Ther 10, 463–476 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00529-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00529-7