Abstract

Introduction

The Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory–Short Form (PROFAD-SSI-SF) is a 19-item patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure to assess pain, fatigue, and dryness in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS). This analysis identified concepts important to measure, and evaluated the content validity and measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF, in patients with pSS.

Methods

Qualitative analyses (GSK Study 208396) used transcripts from an online concept elicitation (CE) discussion forum with patients with pSS and interviews with key opinion leaders (KOLs) to finalize a disease model depicting important concepts for patients with pSS. Cognitive debriefing (CD) interviews with patients with pSS were conducted to further evaluate the content validity of the PROFAD-SSI-SF. Quantitative analyses (GSK Study 213253) used post hoc analyses of blinded data from a phase 2 trial to assess PROFAD-SSI-SF measurement properties.

Results

The CE discussion forum (N = 46) revealed dryness (oral 87.0%, ocular 73.9%, cutaneous 37.0%, vaginal 23.9%, nasal 15.2%, otic 6.5%), pain (89.1%), and fatigue (87.0%) as the most reported symptoms. KOLs (N = 5) found the concepts identified in the disease model accurate and understandable, and confirmed that PROs used in pSS studies should focus on dryness, joint pain, and fatigue. In the CD interviews (N = 20), of the 19 participants asked, all found the PROFAD-SSI-SF easy to understand, and 14/19 items were considered relevant by ≥ 18/20 participants. The quantitative analyses found an acceptable fit of the PROFAD-SSI-SF factor structure, with adequate internal consistency, test–retest reliability, convergent validity with other PRO measures, known-groups validity with Patient Global Assessment, and ability to detect change in patients with pSS.

Conclusion

The final disease model confirmed that the PROFAD-SSI-SF assesses concepts that are relevant and important to patients with pSS. Our findings support the content validity and measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF as a fit-for-purpose PRO measure appropriate for use in clinical trials in patients with pSS.

Clinical Trial Registration number for the phase 2 trial

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02631538

Plain Language Summary

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a disease where the immune system attacks the body, causing a number of symptoms, most notably dryness (sicca) of the eyes and mouth. The Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory–Short Form (PROFAD-SSI-SF) is a questionnaire for patients with pSS that asks about their symptoms. This paper evaluates how relevant the PROFAD-SSI-SF questions are to patients with pSS, and how consistently and accurately the questionnaire can measure changes in their symptoms. We reviewed information about the symptoms and impacts of pSS from an online discussion forum for patients with pSS. Patients said that dryness, fatigue, and pain were the symptoms that most affected their day-to-day lives and well-being. We combined this information with previous research on pSS to design a diagram explaining the key symptoms and day-to-day impacts of pSS, which was reviewed by five experts in pSS. In doing so, we aimed to confirm whether the most important things to patients about living with pSS are asked in the PROFAD-SSI-SF questionnaire. Next, we asked 20 patients with pSS how easy they found the PROFAD-SSI-SF to complete and if any important concepts were missing; they reported that the PROFAD-SSI-SF was easy to fill in and that the important questions were included. Finally, we looked at data from a clinical trial that used the PROFAD-SSI-SF and found it accurately measures changes in symptoms of patients with pSS. This means that the PROFAD-SSI-SF could be used in clinical trials to help assess new medicines for pSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory–Short Form (PROFAD-SSI-SF) is a 19-item questionnaire for assessing symptoms in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS), primarily dryness (sicca), fatigue, and pain. |

The development of the questionnaire predates US Food and Drug Administration guidance on patient-reported outcomes; therefore, validation studies are required to confirm that it meets current requirements for use in clinical trials. |

What did the study ask/what was the hypothesis of the study? |

In addition to refining an existing disease model, this study used qualitative data from patients with pSS and quantitative data (blinded) from a phase 2 clinical trial study of belimumab and rituximab for pSS (NCT02631538) to evaluate the content validity and measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF to determine whether it is fit for purpose for use in patients with pSS. |

What were the study outcomes/conclusions? |

The study results support the content validity of the PROFAD-SSI-SF and showed good reliability, construct validity, and ability to detect change, thus confirming its measurement properties and that it is fit for purpose and relevant for use in patients with pSS. |

What is learned from the study? |

The PROFAD-SSI-SF is a fit-for-purpose patient-reported outcome measure appropriate for use in clinical trials supporting drug development in pSS. |

Introduction

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by mucosal tissue dryness (sicca; e.g., ocular or oral) [1, 2]. Other complications of pSS include: major organ and joint involvement [3, 4]; neuropathies [3, 5]; and increased risk of lymphomas [6, 7].

Key symptoms described by patients with pSS include fatigue [8], dryness, most notably of the mouth and eyes, and pain [2, 9]. Patients also report negative impacts on their health-related quality of life as a result of pSS [10, 11].

Outcome measures typically used in clinical trials in patients with pSS aim to evaluate the symptoms—including mucosal dryness and fatigue [12,13,14]—and impacts of the disease. The Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory–Short Form (PROFAD-SSI-SF) questionnaire is a 19-item patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure divided into eight domains of pSS symptoms (somatic fatigue, mental fatigue, arthralgia, vascular dysfunction, and oral, ocular, cutaneous, and vaginal dryness) scored on an eight-point (0–7) numeric rating scale [15]. The PROFAD-SSI-SF is derived from the 64-item PROFAD-SSI long-form questionnaire; it uses the same eight domains [15] and was developed and validated using a UK cohort of patients with pSS [16, 17]. The PROFAD-SSI-SF has been shown to have a high correlation across all domains (Spearman’s p between 0.779 and 0.996; p < 0.01) and a similar internal structure to the PROFAD-SSI long-form questionnaire, with the advantage that its shorter length is more convenient in clinical trial settings, as it reduces the reporting burden on patients [15].

The development of the questionnaire predates US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on patient-reported outcomes [18]. Further validation of the PROFAD-SSI-SF will confirm it meets FDA requirements for PROs [18] and support its use as a clinical trial endpoint. In addition, validation in patients with pSS and organ involvement would encourage the use of the PROFAD-SSI-SF in future clinical trials of new disease-modifying therapies, particularly in light of the interest in biologic therapies for this patient population [19, 20].

This paper describes research that aimed to confirm the key concepts that should be measured in patients with pSS, and to confirm that the PROFAD-SSI-SF assesses these key concepts with the appropriate measurement properties for it to be used in clinical trials in patients with pSS.

Methods

Study Design

A targeted literature review and qualitative analyses, including a secondary analysis of transcripts from an online concept elicitation (CE) discussion forum, and key opinion leader (KOL) interviews were conducted to develop and refine a previously developed disease model of pSS and identify important concepts to be measured in patients with pSS.

Qualitative cognitive debriefing (CD) interviews with patients with pSS were conducted as a final step to confirm the content validity of the PROFAD-SSI-SF. The quantitative study (GSK Study 213253) evaluated the measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF using blinded data from a phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of belimumab and rituximab in patients with symptomatic and systemically active (European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology [EULAR] Sjögren’s Syndrome Disease Activity Index [ESSDAI] ≥ 5 points) pSS (GSK Study 201842; NCT02631538) [21, 22].

Refining a Disease Model for pSS: Qualitative Analysis

CE Discussion Forum: Secondary Analysis

Transcripts from a previous online CE discussion forum (GSK Study 208399) that gathered information on symptoms, disease impacts, treatment experiences, and goals from 46 patients with pSS [23] were analyzed to confirm and refine the key concepts presented in a draft disease model developed from a targeted literature review. Findings from the CE study were also used to inform the creation of interview materials for subsequent CD interviews with patients with pSS. For full details, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

KOL Interviews

Ninety-minute, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with five KOLs (three rheumatologists and two patient advocates) to further refine the disease model and identify the concepts of the greatest importance to patients with pSS. For full details, please refer to the Supplementary Material.

PROFAD-SSI-SF Evaluation: Qualitative Analyses

CD Interviews

Trained researchers conducted 90-min, one-on-one, semi-structured interviews with patients with pSS to confirm the content validity of the PROFAD-SSI-SF for use in pSS. During the interviews, patients also reviewed and discussed the EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients Reported Index (ESSPRI) [24, 25]—developed to assess patients’ symptoms and disease activity—but these findings are not reported here, as this manuscript focuses on the qualitative results of the PROFAD-SSI-SF.

Participants were recruited from a pre-existing patient panel via a non-profit organization that supports patients with pSS. Eligible participants were: adults aged ≥ 18 years; fluent in English (i.e., able to read, write, and fully understand US English); and able to provide a physician-confirmed diagnosis of pSS with organ involvement (to facilitate the future use of PROFAD-SSI-SF in patients with organ involvement). “Organ involvement” was defined as disease activity in ≥ 1 of the following categories based on the ESSDAI [26]: fever of non-infectious origin; lymphadenopathy/lymphoma; arthralgia/synovitis; erythema/vasculitis/purpura; pulmonary involvement; renal involvement; myositis; peripheral/central nervous system involvement; cytopenia of autoimmune origin (with neutropenia) and/or anemia and/or thrombocytopenia and/or lymphopenia. Eligible participants were further screened to select representative members of the target sample, aiming for diversity across disease severity, type of organ involvement, sex, race, education, and time since diagnosis.

CD interviews were conducted either in person at specially equipped locations or remotely using WebEx meeting software. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to each interview. Each interview had a four-part structure that included an introduction to the study, initial rapport-building questions, a review of the PROFAD-SSI-SF using the “think-aloud” method as well as targeted questions to address each element of the instrument, and a conclusion (Fig. 1). The CD interview model was not tested in a sample population in this study. However, this model has been widely used and reported previously, including in patients with pSS [27, 28], and is generally considered a robust and reliable approach for qualitative studies that is well received by participants. Furthermore, the think-aloud component of the interview was implemented only after participants were familiar with this approach through practice with an item unrelated to the PROFAD-SSI-SF at the beginning of the interviews. Interviews were transcribed, deidentified, and reviewed for quality against audio recordings. All transcripts were coded and analyzed using a Microsoft Excel workbook. The transcripts were coded to identify any issues or potential problems with each element of the PROFAD-SSI-SF (i.e., the instructions, items, response choices, recall period) with the aim of evaluating the relevance, comprehensibility, and comprehensiveness of the instrument. All responses were evaluated by researchers and assigned codes to capture the type of feedback and whether remarks were spontaneous or prompted after questioning by the interviewer. Rater agreement was evaluated and reached using an iterative process whereby transcripts were coded by a trained analyst and then reviewed by a second researcher. Discrepancies between raters were identified. Follow-up consensus meetings were then held with the raters and study team to discuss any discrepancies and finalize the coding structure and rules. All coding was then reviewed and confirmed by the first author, who was the primary qualitative investigator on the study.

The four-part structure of the cognitive debriefing interview procedure. aESSPRI was also discussed during the cognitive debriefing interviews. ESSPRI European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Sjögren’s Syndrome Patients Reported Index, PROFAD-SSI-SF Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory–Short Form, pSS primary Sjögren’s syndrome

The sample size for CD interviews was determined using the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) PRO Good Research Practices Task Force guidelines and information from the literature [29, 30]. A total sample size of 20 patients was determined to be sufficient to test the understandability and comprehensiveness of the PROFAD-SSI-SF items.

PROFAD-SSI-SF Evaluation: Quantitative Analyses

The quantitative analysis included a post hoc psychometric analysis of blinded data from the phase 2 study described above [21, 22]. Calculations to determine sample size were not performed, as this analysis used existing data.

Test of Structure

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed for the items and domains of the PROFAD-SS-SF to provide empirical support for its conceptual framework. An uncorrelated factor structure was used to estimate factors and single-item domains were excluded from models.

A multi-factor multi-visit model combined item responses from the screening, week 24, and week 52 visits to examine the model fit or pattern of factor loadings using data from all visits. This approach was used to increase power with a larger sample size compared with a single-visit model; it was also preferred over other models attempted based on an assessment of model fit. Model fit was evaluated using three indicators: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), in which values closer to 1 indicate better fit [31]; the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), where values closer to 1 indicate a better fit and values ≥ 0.95 are deemed as indicating an acceptable fit [32]; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), in which a value of 0 indicates a perfect model fit and values < 0.08 are considered to indicate an acceptable fit [33]. Factor loadings of items onto domains and summary scores were examined to interpret the pattern of relationships of the items to domains and summary scores within the context of the hypothesized structure.

Reliability

Internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha, calculated from screening visit data for each multi-item domain for PROFAD-SSI-SF, with the a priori cutoff of 0.7 indicating adequate internal consistency [34, 35].

For test–retest reliability, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated from two-way mixed-effects models for the PROFAD-SSI-SF domain and summary scores using data from the screening and week 24 visits. Test–retest reliability was examined using each of two different stability criteria. Criterion 1 defined stability as a change of ≤ 1 point on the Patient Global Assessment (PtGA), whereas criterion 2 defined stability as a change of ≤ 1 point on the Physician Global Assessment (PGA). ICC values between 0.50 and 0.75 and between 0.75 and 0.90 indicate moderate and good reliability, respectively [36].

Construct Validity

Convergent/discriminant validity was determined by assessing the convergence between the domains and summary scores of the PROFAD-SSI-SF and similar criterion measures from the ESSPRI (dryness, fatigue, pain, and total score), PtGA, PGA, oral dryness 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS), ocular dryness 11-point NRS, ESSDAI, Schirmer’s test, and stimulated and unstimulated salivary flow tests. Only correlation coefficients > 0.30 were considered to be adequately supportive of convergent validity [37].

Known-groups validity analyses compared each of the PROFAD-SSI-SF domain and summary scores with the PtGA, where severity groups were defined as mild (PtGA score of 0–3), moderate (PtGA score of 4–6), and severe (PtGA score of ≥ 7). The analyses used separate one-way between-patient analysis of variance (ANOVA) models. When the omnibus F-test was statistically significant, post hoc tests for pairwise comparisons among groups were conducted, using Sidak corrections to control for family-wise type I error due to multiplicity. As very few patients met the criteria for mild severity at screening (n = 6), it was decided that data from the week 24 visit would be used instead.

Ability to Detect Change

Correlations between changes in PROFAD-SSI-SF domain and summary scores from screening to weeks 24 and 52 and changes in PGA, PtGA, oral dryness 11-point NRS, ocular dryness 11-point NRS, and ESSDAI during the same time intervals were analyzed. Acceptable levels of concordance were deemed correlations ≥ 0.30.

A second approach assessed the difference in the mean change in PROFAD-SSI-SF domain and summary scores at weeks 24 and 52 across three responder subgroups, defined as those with a large improvement in PtGA (a decrease of ≥ 4 points), a small improvement (a decrease of 2 or 3 points), or no change/worsening (≥ − 1 point), as assessed using separate one-way between-patient ANOVA models. When the omnibus F-test was statistically significant, post hoc tests for pairwise comparisons among groups were conducted, using Sidak corrections to control for family-wise type I error due to multiplicity.

Analyses of Within-Patient Meaningful Change

Exploratory, anchor-based, participant-meaningful change analyses were conducted by examining standardized response means of PROFAD-SSI-SF summaries when anchored to the PtGA. Several cutoffs were examined in order to identify an inflection point in the summary scores. The definition of meaningful change identified used a PtGA cutoff of ≥ 3 points of improvement (i.e., a change of − 3 points) or a ≥ 30% improvement between screening and weeks 24 and 52. Corresponding values were derived using this definition for each scale by examining the respective changes in summary scores across weeks 24 and 52.

In addition, two distribution-based approaches for estimating the magnitude of meaningful change in PRO scores was performed; one approach used one-half of the measure’s standard deviation for scores at screening [38], while the other calculated the standard error of measurement [39].

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

Ethical considerations for the online CE discussion forum and the phase 2 study are summarized elsewhere [21,22,23].

For the CD interviews, all patients provided informed consent and the study was overseen by an independent review board (IRB) or ethics committee (IRB# 120190199).

Results

Refining a Disease Model for pSS: Qualitative Analysis

CE Discussion Forum: Secondary Analysis

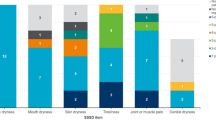

Results from the secondary analysis of the online patient forum discussion transcripts (n = 46 participants) centered on symptom experience and burden of illness (e.g., symptoms and physical, social, emotional, and financial impacts) and treatment experience (e.g., prescription and over-the-counter medications taken, effectiveness of treatments, and treatment preferences), and confirmed the concepts of greatest importance for measurement that had been drafted based on the literature. Common symptoms and related comorbidities, impacts, and triggers reported by participants are shown in Fig. 2. According to the forum participants, dryness (oral: 87.0% [n = 40/46], ocular: 73.9% [n = 34/46], cutaneous: 37.0% [n = 17/46], vaginal: 23.9% [n = 11/46], nasal: 15.2% [n = 7/46], otic: 6.5% [n = 3/46]), pain (89.1% [n = 41/46]), and fatigue (87.0% [n = 40/46]) were the most commonly reported symptoms, affecting almost all aspects of functioning and well-being (Fig. 2).

KOL Interviews

Overall, the KOLs found the key concepts accurate and the disease model appropriate in its representation of the causes, signs, symptoms, triggers, and impacts of pSS. They also confirmed that any PRO used in a pSS-specific study should focus on dryness, joint pain, and fatigue.

The final disease model is presented in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material. It describes pSS in terms of causes, signs, symptoms, and exacerbating factors or triggers and summarizes the impact of pSS on patients’ functioning and well-being.

PROFAD-SSI-SF Evaluation: Qualitative Analyses

CD Interviews

Twenty patients with pSS (Table S2 in the Supplementary Material) took part in the CD interviews; 14 attended the interviews in person and 6 attended remotely. Data analysis did not identify any differences in the findings between these two modes of data collection.

Overall, participants had positive feedback on the PROFAD-SSI-SF; comprehensiveness and relevance were cited as the questionnaire’s strengths. All participants asked found the items easy to understand (100.0% [n = 19/19]), most (90.0% [n = 18/20]) reported no difficulty when choosing answers, and the majority (≥ 18/20 participants [≥ 90.0%]) considered 14 of the 19 items relevant to their experiences with pSS. Most participants felt that the questionnaire was an appropriate length (83.3% [n = 15/18]) and had an appropriate recall period (70.0% [n = 14/20]). Around half thought that it was sufficiently comprehensive (55.0% [n = 11/20]), although some suggested additional items for inclusion, such as comorbidities, dry hair, changes in vision, swelling in other places than fingers or wrists, mucus, stomach irritation, dry lips, joint pain, tinnitus, constipation, anxiety, depression, and brain fog. Participants did not report any problems with item content for 11 of the 19 items. Some patients made suggestions for modifications (e.g., revisions or removal) to the remaining eight items; however, these recommendations were not reported consistently across the sample.

PROFAD-SSI-SF Evaluation: Quantitative Analyses

Test of Structure

The domains of the PROFAD-SSI-SF were confirmed by CFA in the multi-factor multi-visit model (Table 1). Evidence supported a good fit with the multi-factor multi-visit model, as indicated by CFI (0.98), TLI (0.99), and RMSEA (0.07), which exceeded the suggested thresholds indicating acceptable fit.

Across all domains, the magnitudes of item-to-factor loadings were large, with all loadings ≥ 0.74 (Table 1). Items for the somatic fatigue and mental fatigue domains had the largest magnitudes over all loading of items, with all ≥ 0.86. The oral dryness domain had the smallest magnitude loadings (0.74–0.85), with difficulty eating the only item within that domain with a loading > 0.80.

Reliability

All domains with multiple items, except for arthralgia, had Cronbach’s alpha values of > 0.80, exceeding the suggested threshold indicating adequate fit (Table 2). These findings showed acceptable internal consistency of the PROFAD-SSI-SF.

For test–retest reliability, only a small number of patients (PtGA [criterion 1]: 34.9% [n = 30/86]; PGA [criterion 2]: 20.9% [n = 18/86]) met the criteria for stability. When stability was defined by PtGA, only one PROFAD-SSI-SF domain (vaginal dryness: 0.85) exceeded the a priori ICC value for good test–retest reliability (≥ 0.75); however, the majority of the domain and summary scores had ICCs ≥ 0.50, indicating at least moderate reliability (Table 2). When stability was defined by PGA (criterion 2), four PROFAD-SSI-SF domains (mental fatigue: 0.81, vaginal dryness: 0.93, ocular dryness: 0.76, SSI summary score: 0.87) showed good reliability; the majority of the domain and summary scores had ICCs ≥ 0.50, indicating at least moderate reliability.

Construct Validity

PROFAD-SSI-SF showed convergent validity with measures derived from patient reports. Correlation coefficients > 0.30, indicating acceptable evidence of convergent validity, were observed between other PROs with most PROFAD-SSI-SF domains and summary scores (Table 3). In particular, the PROFAD-SSI-SF fatigue (especially somatic fatigue) domain scores and the PROF summary score were strongly associated with the ESSPRI fatigue scores. Also, the PROFAD-SSI-SF ocular and oral dryness domains showed strong associations with the respective ESSPRI and NRS scales. Associations with other scales measuring dryness were generally weaker for the cutaneous dryness and vaginal dryness domains of the PROFAD-SSI-SF. PROFAD-SSI-SF did not show convergence with clinical measures (PGA, ESSDAI) nor biomarkers (Table 3).

For known-groups validity, all domain and summary scores of the PROFAD-SSI-SF showed statistically significant differences across the three severity groups (all F ≥ 3.72, all p ≤ 0.03) with measures derived from patient reports (Table 4). Pairwise Sidak tests showed that, for all domains, the severe group scored statistically significantly worse than the mild group.

Ability to Detect Change

Acceptable levels of concordance (correlations ≥ 0.30) were observed between changes in PROFAD-SSI-SF and changes in other PROs (PtGA, oral dryness NRS, and ocular dryness NRS) from screening to weeks 24 and 52, except for the PROF and PROFAD summary scores with ocular dryness NRS at week 52 (Table 5). The majority of the correlation coefficients (i.e., 31 of 48) for change between the PROFAD-SSI-SF domains and the PROs were ≥ 0.30. No correlations ≥ 0.30 were observed for the cutaneous dryness domain, while only one correlation, with the PtGA at week 24, exceeded 0.30 for the vaginal dryness domain.

All correlation coefficients between changes in the domain and summary scores of the PROFAD-SSI-SF and changes in clinician-rated outcomes—ESSDAI score and PGA—were small (i.e., ≤ 0.33; see Table 5).

In a comparison of responder groups defined by change in PtGA, omnibus tests for all ANOVA models were statistically significant (p < 0.05), except for the vascular dysfunction domain at week 24, vaginal dryness domain at week 52, and cutaneous dryness domain at both weeks 24 and 52 (Table 6).

Analyses of Meaningful Change

Corresponding values for meaningful change were approximately 1.5 to 2 points for PROF and PROFAD and 1.5 points for improvement in SSI summary scores (Table 7). The two distribution-based approaches of meaningful change generally showed agreement, indicating an approximately meaningful change of approximately 1 point.

Discussion

Overall, these analyses support the content validity and measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF for use among patients with pSS.

The final disease model confirmed that the items and content of the PROFAD-SSI-SF assess the most relevant and important concepts to patients with pSS. The results of the CE forums and KOL interviews emphasized the importance of the impact of dryness, pain, and fatigue when evaluating burden of disease and treatment benefits in patients with pSS. Dryness, pain, and fatigue have previously been reported as symptoms central to pSS [25, 40,41,42], and key expert panel discussions have also highlighted fatigue as a particularly important outcome domain in relation to patients’ disease experiences [43, 44].

In this study, the CD interviews confirmed that the concepts contained within the PROFAD-SSI-SF were appropriate to measure dryness, pain, and fatigue in patients with pSS and were understandable, with most items considered relevant by most patients. Problems with the questions reported by participants in the CD interviews were infrequent and generally focused on the redundancy of some items or personal preferences (e.g., changing “hard to see ATM or computer screen” in item 14’s list of examples to reflect cell phone screens). However, because feedback about redundancies was inconsistent and none of the issues impacted participants’ ability to understand the items as intended, no changes to the instrument are proposed. Some patients reported concepts (e.g., gastrointestinal issues, changes in vision, dry hair) related to their experience with pSS that they felt were missing from the PROFAD-SSI-SF. However, the use of the PROFAD-SSI-SF in combination with other PRO instruments that assess those concepts not included in the PROFAD-SSI-SF has the potential to facilitate a comprehensive holistic assessment of the experience of patients with pSS.

Importantly, the CD interviews were conducted in patients with pSS and organ involvement. This allowed the PROFAD-SSI-SF to be validated in this group of patients. While a minority of patients have high disease activity and/or severe organ involvement [45], pain, fatigue, and dryness are cardinal symptoms of pSS, and are the aspects patients most wish to improve [23].

In our quantitative analysis, patients were evaluated at weeks 24 and 52, in line with the interim and primary analysis data available, respectively, from the phase 2 study (GSK Study 201842) that assessed the efficacy and safety of belimumab and rituximab in patients with pSS [21, 22]. The PROFAD-SSI-SF, PtGA, and PGA were not performed after week 52. However, none of the described analyses considered treatment manipulations, and the intent was to evaluate the measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF. Where stratification of participants was performed, stratification was based on indications of change as indicated by other specified assessment variables such as the PtGA or disease activity as measured by ESSDAI. The quantitative analyses confirmed an acceptable fit of the factor structure of the PROFAD-SSI-SF, as well as good internal consistency, construct validity, and ability to detect change in patients with pSS. Consistent with our findings, a previous study performed to validate the SSI—a component of the PROFAD-SSI-SF—also reported that it was a measure with good construct validity that captured some of the most important symptoms associated with pSS [17]. Another study reported that the PROFAD had a similar structure to the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), but with better resolution of somatic fatigue facets than the MFI [40]. Similarly, results of a previous study assessing the sensitivity of the questionnaire in distinguishing fatigue in patients with pSS, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis indicated that the PROFAD-SSI-SF was an appropriate tool to assess whether the severity of fatigue is pathological in patients with pSS [16]. The sensitivity of the PROFAD-SSI-SF was greater than the Medical Outcome Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey in the measurement of patient status [16, 46].

In terms of concordance between the PROFAD-SSI-SF and clinical assessments (such as the PGA, ESSDAI, and Schirmer test), the quantitative analysis revealed no or poor concordance between these measures, whereas there was acceptable concordance between the PROFAD-SSI-SF and other PROs; for example, the oral dryness NRS and ocular dryness NRS. This is comparable with several studies in pSS that have reported only weak or moderate correlations between PRO measures and clinical assessments but relatively high correlations with other PROs [17, 47,48,49,50]. Also, a recent randomized controlled trial found that clinical measures improved with the study drug, whereas ESSPRI and PtGA did not [51]. The consistency of this observation across different PROs and studies points to a disconnect between patients’ and clinicians’ assessments of symptom severity in pSS, rather than patients having difficulties with a particular measure or being inconsistent in their reporting. Altogether, this suggests that the PROFAD-SSI-SF captures patient experiences of the disease that are potentially not well reflected in clinical measures. Therefore, to get a complete picture of patient burden and treatment benefits, it could be beneficial to utilize a complementary measure such as the PROFAD-SSI-SF along with clinical measures.

The ESSDAI and the ESSPRI were developed to measure disease activity and key pSS symptoms, respectively, in clinical trials, and have become commonly used when investigating the effectiveness of new therapies [48, 52, 53]. While the ESSPRI uses a single visual analogue scale per symptom or concept, the multi-question PROFAD-SSI-SF may reveal more information while being of an appropriate length for use as an outcome measure in clinical trials.

This study has some limitations. The secondary analysis of the CE discussion forum was performed on a pre-existing dataset, making it impossible to ask follow-up questions, and furthermore, the sample size of the phase 2 trial was based on the primary study objective (to investigate safety and tolerability); therefore, it was not sized for the purpose of the current quantitative analyses. In addition, the method used to collect CE discussion forum data meant that consistent information was not always collected for all participants. Nonetheless, analysis confirmed that saturation of concepts was achieved. In addition, the KOL interviews served to add information and insight to the outcomes of the discussion forum. The test–retest reliability results should be interpreted with caution due to the relatively long 6-month time interval between test and retest, which is longer than typically applied in psychometric validations of PROs [54]. Given this longer time interval, few patients would be expected to remain stable in a clinical trial setting. As expected, only a small number of patients met the criteria for stability, and those analyses were underpowered due to small sample sizes, increasing the likelihood of imprecise ICC estimates.

Despite some limitations, results from this study provide valuable information from a patient perspective about dryness, pain, and fatigue associated with pSS. Moreover, it has been argued that randomized controlled trials should use specific and validated definitions of endpoints and use evidence-based selection of the most treatment-responsive pSS domains [55]. The results presented here support the use of the PROFAD-SSI-SF in such clinical trials.

Conclusions

Findings from this study support the content validity and measurement properties of the PROFAD-SSI-SF, a fit-for-purpose PRO measure appropriate for use among patients with pSS in clinical trials supporting drug development. The content validity of PROFAD-SSI-SF was further demonstrated by the final disease model, where it was confirmed that PROFAD-SSI-SF assessed the most relevant and important concepts to patients with pSS. The results of this study highlight the importance of including PRO measures such as the PROFAD-SSI-SF in clinical trials and clinical practice, as clinical ratings are not sufficient by themselves to capture patient health and treatment benefit.

References

Del Papa N, Vitali C. Management of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: recent developments and new classification criteria. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2018;10(2):39–54.

Mariette X, Criswell LA. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):931–9.

Garcia-Carrasco M, Ramos-Casals M, Rosas J, Pallares L, Calvo-Alen J, Cervera R, Font J, Ingelmo M. Primary Sjogren syndrome: clinical and immunologic disease patterns in a cohort of 400 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2002;81(4):270–80.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Seror R, Bootsma H, Bowman SJ, Dorner T, Gottenberg JE, Mariette X, Theander E, Bombardieri S, et al. Characterization of systemic disease in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: EULAR-SS Task Force recommendations for articular, cutaneous, pulmonary and renal involvements. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(12):2230–8.

Brito-Zeron P, Theander E, Baldini C, Seror R, Retamozo S, Quartuccio L, Bootsma H, Bowman SJ, Dorner T, Gottenberg JE, et al. Early diagnosis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: EULAR-SS task force clinical recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(2):137–56.

Theander E, Henriksson G, Ljungberg O, Mandl T, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Lymphoma and other malignancies in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a cohort study on cancer incidence and lymphoma predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(6):796–803.

Zintzaras E, Voulgarelis M, Moutsopoulos HM. The risk of lymphoma development in autoimmune diseases: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(20):2337–44.

Karageorgas T, Fragioudaki S, Nezos A, Karaiskos D, Moutsopoulos HM, Mavragani CP. Fatigue in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: clinical, laboratory, psychometric, and biologic associations. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(1):123–31.

Omdal R, Mellgren SI, Norheim KB. Pain and fatigue in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;60(7):3099–106.

Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Huddleston Slater JJ, Spijkervet FK, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A, Bootsma H. Health-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(9):1077–82.

Segal B, Bowman SJ, Fox PC, Vivino FB, Murukutla N, Brodscholl J, Ogale S, McLean L. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome: health experiences and predictors of health quality among patients in the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:46.

Dass S, Bowman SJ, Vital EM, Ikeda K, Pease CT, Hamburger J, Richards A, Rauz S, Emery P. Reduction of fatigue in Sjogren syndrome with rituximab: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(11):1541–4.

Vivino FB, Al-Hashimi I, Khan Z, LeVeque FG, Salisbury PL 3rd, Tran-Johnson TK, Muscoplat CC, Trivedi M, Goldlust B, Gallagher SC. Pilocarpine tablets for the treatment of dry mouth and dry eye symptoms in patients with Sjogren syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, multicenter trial. P92–01 Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(2):174–81.

Norheim KB, Harboe E, Goransson LG, Omdal R. Interleukin-1 inhibition and fatigue in primary Sjogren’s syndrome—a double blind, randomised clinical trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30123.

Bowman SJ, Hamburger J, Richards A, Barry RJ, Rauz S. Patient-reported outcomes in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: comparison of the long and short versions of the Profile of Fatigue and Discomfort–Sicca Symptoms Inventory. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(2):140–3.

Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG, UK Sjögren's Interest Group. Measurement of fatigue and discomfort in primary Sjogren’s syndrome using a new questionnaire tool. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(6):758–64.

Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG, Field A, Rostron J, UK Sjögren's Interest Group. Validation of the Sicca Symptoms Inventory for clinical studies of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(6):1259–66.

US FDA. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Rockville: US FDA; 2009. https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download.

Carsons SE, Vivino FB, Parke A, Carteron N, Sankar V, Brasington R, Brennan MT, Ehlers W, Fox R, Scofield H, et al. Treatment guidelines for rheumatologic manifestations of Sjogren’s syndrome: use of biologic agents, management of fatigue, and inflammatory musculoskeletal pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(4):517–27.

Manfre V, Cafaro G, Riccucci I, Zabotti A, Perricone C, Bootsma H, De Vita S, Bartoloni E. One year in review 2020: comorbidities, diagnosis and treatment of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38 Suppl 126(4):10–22.

Mariette X, Baldini C, Barone F, Bootsma H, Clark K, De Vita S, Lerang K, Mistry P, Morin F, Punwaney R, et al. Op0135 safety and efficacy of subcutaneous belimumab and intravenous rituximab combination in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled 68-week study. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2021;80(suppl 1):78–79.

van Maurik A, Gardner D, Nayar S, Smith C, Clark K, Mistry P, Punwaney R, Roth D, Henderson R, Mariette X, et al. Sequential administration of belimumab and rituximab in primary Sjögren’s syndrome reduces minor salivary gland-resident B cells and delays B-cell repopulation in circulation (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(suppl 10).

Gairy K, Ruark K, Sinclair SM, Brandwood H, Nelsen L. An innovative online qualitative study to explore the symptom experience of patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(3):601–15.

Seror R, Theander E, Bootsma H, Bowman SJ, Tzioufas A, Gottenberg JE, Ramos-Casals M, Dorner T, Ravaud P, Mariette X, et al. Outcome measures for primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2014;51:51–6.

Seror R, Ravaud P, Mariette X, Bootsma H, Theander E, Hansen A, Ramos-Casals M, Dorner T, Bombardieri S, Hachulla E, et al. EULAR Sjogren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI): development of a consensus patient index for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):968–72.

Seror R, Ravaud P, Bowman SJ, Baron G, Tzioufas A, Theander E, Gottenberg JE, Bootsma H, Mariette X, Vitali C, et al. EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity index: development of a consensus systemic disease activity index for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):1103–9.

Ndife B, Fenel S, Lewis S, Agashivala N. Development of a symptom diary for use in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome (abstract). Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73(suppl 10).

Prior Y, Tennant A, Tyson S, Hammond A. The Valued Life Activities Scale (VLAs): linguistic validation, cultural adaptation and psychometric testing in people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the UK. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):505.

Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, Ring L. Content validity—establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report, part 2: assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14(8):978–88.

Turner-Bowker DM, Lamoureux RE, Stokes J, Litcher-Kelly L, Galipeau N, Yaworsky A, Solomon J, Shields AL. Informing a priori sample size estimation in qualitative concept elicitation interview studies for clinical outcome assessment instrument development. Value Health. 2018;21(7):839–42.

Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–46.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res. 1992;21(2):230–58.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein I. Psychometric theory. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994.

Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98–104.

Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–63.

Cappelleri JCZK, Bushmakin AG, Alvir JM, Alemayehu D, Symonds T. Patient-reported outcomes: measurement, implementation and interpretation. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press; 2013.

Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care. 2003;41(5):582–92.

Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Wolinsky FD. Further evidence supporting an SEM-based criterion for identifying meaningful intra-individual changes in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(9):861–73.

Goodchild CE, Treharne GJ, Booth DA, Kitas GD, Bowman SJ. Measuring fatigue among women with Sjogren’s syndrome or rheumatoid arthritis: a comparison of the Profile of Fatigue (ProF) and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI). Musculoskeletal Care. 2008;6(1):31–48.

Arends S, Meiners PM, Moerman RV, Kroese FG, Brouwer E, Spijkervet FK, Vissink A, Bootsma H. Physical fatigue characterises patient experience of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(2):255–61.

Hammitt KM, Naegeli AN, van den Broek RWM, Birt JA. Patient burden of Sjogren’s: a comprehensive literature review revealing the range and heterogeneity of measures used in assessments of severity. RMD Open. 2017;3(2):e000443.

Bowman SJ, Pillemer S, Jonsson R, Asmussen K, Vitali C, Manthorpe R, Sutcliffe N, Contributors to and participants at the workshop. Revisiting Sjogren’s syndrome in the new millennium: perspectives on assessment and outcome measures. Report of a workshop held on 23 March 2000 at Oxford, UK. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40(10):1180–8.

Pillemer SR, Smith J, Fox PC, Bowman SJ. Outcome measures for Sjogren’s syndrome, April 10–11, 2003, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(1):143–9.

Oni C, Mitchell S, James K, Ng WF, Griffiths B, Hindmarsh V, Price E, Pease CT, Emery P, Lanyon P, et al. Eligibility for clinical trials in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: lessons from the UK Primary Sjogren’s Syndrome Registry. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(3):544–52.

Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey, manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre; 1993.

Hay EM, Thomas E, Pal B, Hajeer A, Chambers H, Silman AJ. Weak association between subjective symptoms or and objective testing for dry eyes and dry mouth: results from a population based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57(1):20–4.

Cornec D, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Mariette X, Jousse-Joulin S, Berthelot JM, Perdriger A, Puechal X, Le Guern V, Sibilia J, Gottenberg JE, et al. Severe health-related quality of life impairment in active primary Sjogren’s syndrome and patient-reported outcomes: data from a large therapeutic trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(4):528–35.

Lendrem D, Mitchell S, McMeekin P, Gompels L, Hackett K, Bowman S, Price E, Pease CT, Emery P, Andrews J, et al. Do the EULAR Sjogren’s syndrome outcome measures correlate with health status in primary Sjogren’s syndrome? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(4):655–9.

Seror R, Theander E, Brun JG, Ramos-Casals M, Valim V, Dorner T, Bootsma H, Tzioufas A, Solans-Laque R, Mandl T, et al. Validation of EULAR primary Sjogren’s syndrome disease activity (ESSDAI) and patient indexes (ESSPRI). Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(5):859–66.

Bowman SJ, Fox R, Dorner T, Mariette X, Papas A, Grader-Beck T, Fisher BA, Barcelos F, De Vita S, Schulze-Koops H, et al. Safety and efficacy of subcutaneous ianalumab (VAY736) in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b dose-finding trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10320):161–71.

de Wolff L, Arends S, van Nimwegen JF, Bootsma H. Ten years of the ESSDAI: is it fit for purpose? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38 Suppl 126(4):283–90.

Juarez M, Diaz N, Johnston GI, Nayar S, Payne A, Helmer E, Cain D, Williams P, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Fisher BA, et al. A phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study of oral seletalisib in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(3):1364–75.

Marx RG, Menezes A, Horovitz L, Jones EC, Warren RF. A comparison of two time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(8):730–5.

Saraux A, Devauchelle-Pensec V. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome: new beginning for evidence-based trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10320):121–2.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Sjögren’s Foundation for their contribution to the recruitment of patients into this study.

Funding

This study was funded by GSK (GSK Studies 208396 and 213253). GSK also funded medical writing and submission support, and the journal's Rapid Servie Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception or design of the study. Kimberly Raymond, Cory D. Saucier, and Meaghan O’Connor were involved in the acquisition of the data. All authors contributed equally to the analysis or interpretation of the data.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing and submission support was provided by Olga Conn, PhD, and Casmira Brazaitis, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK, part of Fishawack Health, and was funded by GSK.

Disclosures

Kimberly Raymond, Cory D. Saucier, Meaghan O’Connor, and Mark Kosinski are employees of QualityMetric, Inc., and Stephen Maher and Aaron Yarlas are former employees of QualityMetric, Inc., which received GSK funding to design and conduct the reported analyses. Wen-Hung Chen and Kerry Gairy are employees of GSK and hold stocks and shares in the company.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical considerations for the online CE discussion forum and the phase 2 study are summarized elsewhere [21,22,23]. For the CD interviews, all patients provided informed consent and the study was overseen by an independent review board (IRB) or ethics committee (IRB# 120190199).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Prior Presentation

Data from this study were previously presented at the ISOQOL 28th Annual Conference, which took place virtually on 12–28 October 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raymond, K., Maher, S., Saucier, C.D. et al. Validation of the PROFAD-SSI-SF in Patients with Primary Sjögren's Syndrome with Organ Involvement: Results of Qualitative Interviews and Psychometric Analyses. Rheumatol Ther 10, 95–115 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00493-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-022-00493-2