Abstract

Introduction

Some patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) using tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) experience inefficacy or lack of tolerability and hence switch to another TNFi (cycling) or to a therapy with another mode of action (switching). This study examined patient characteristics, prescribing patterns and treatment practice for RA in the United States.

Methods

Data were from the Adelphi Disease Specific Programme (Q2–Q3 2016). Rheumatologists completed a survey and patient record forms for adult patients with RA who had received ≥ 1 targeted therapy. Patients were grouped by class of first-used targeted therapy, and monotherapy vs. combination therapy. TNFi patients who received ≥ 1 targeted therapy were classified as cyclers or switchers. Univariate analyses compared patient characteristics and physician factors across the analysis groups.

Results

Overall, 631 patients received ≥ 1 targeted therapy; 535 were prescribed a TNFi as first targeted therapy, 53 a nonTNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD), and 43 tofacitinib. Of 577 patients with known conventional synthetic (cs) DMARD status, 18.7% were prescribed monotherapy and 81.3% combination therapy. Combination therapy patients received significantly more concomitant medications prior to initiation of first targeted therapy than monotherapy patients (P < 0.05). The top reason for physicians to prescribe first use targeted therapy was strong overall efficacy (79.9%). Of 163 patients who progressed to second targeted therapy, 60.7% were cyclers. A lower proportion of cyclers persisted on their first use targeted therapy versus switchers (P = 0.03). The main reason physicians gave for switching patients at this stage was worsening condition (46.6%).

Conclusions

Most patients were prescribed a TNFi as their first targeted therapy; over half then cycled to another TNFi. This suggests other factors may influence second use targeted treatment choice and highlights the need for greater understanding of outcomes associated with subsequent treatment choices and potential benefits of switching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Combination therapy with a targeted disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and a conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) is recommended in clinical guidelines for patients who fail to respond to csDMARDs alone. |

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are routinely used following csDMARD failure; however, patients experiencing inefficacy and lack of tolerability with their first TNFi can cycle to another TNFi or switch to another targeted therapy with a different mode of action (MOA). There is little in the literature on prescribing patterns of rheumatologists in the U.S. and the reasons behind their prescribing behavior. |

What was learned from the study? |

The top reasons physicians gave for selecting a specific targeted therapy were strong overall efficacy, inhibition of disease progression, and reduction in stiffness. There were few significant differences in physician reasoning by class of treatment. |

Of physicians surveyed, almost three quarters believed that there was some class effect with TNFi. |

At second use targeted therapy, 60.7% of patients were cycled to another TNFi and 39.3% switched to a therapy with a different MOA. The main reasons physicians gave for switching from first use targeted therapy were worsening condition, secondary lack of efficacy, and primary lack of efficacy. |

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease, affecting 1.28–1.36 million adults in the United States (estimates from 2014) and with a global prevalence estimated of 0.24% (estimate from 2010) [1].

Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic agents (csDMARDs) form the basis of care in RA. However, in patients who do not achieve low disease activity or disease remission with csDMARDs, guidelines recommend targeted therapy with a biologic DMARD (bDMARD) or small molecule (targeted-synthetic DMARD [tsDMARD]), preferably in combination with a csDMARD [2, 3].

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) are routinely used first following csDMARD monotherapy failure [2, 3], as they are effective in reducing the signs and symptoms of RA and preventing the progression of joint damage [4,5,6,7]. Patients who experience inefficacy and lack of tolerability with their first TNFi tend to either cycle to another TNFi (TNFi cycling) [8, 9] or switch to targeted nonTNFi therapies with different mechanisms of action (MOA; MOA switching). Studies have demonstrated that MOA switching at second use targeted therapy is often associated with better clinical outcomes [10,11,12], higher treatment persistence [10], and lower healthcare costs [13].

Although guidelines recommend targeted therapy combined with a csDMARD [2, 3], a previous study found that approximately 60% of patients were not taking csDMARDs as recommended [14]. Such research demonstrates that either patients are non-adherent to their medication or patients are not being prescribed combination therapy by their physicians.

Given the increasing availability of treatment options, there is a growing emphasis on more personalized treatment strategies for patients with RA [8], and understanding current targeted therapy combination with csDMARDs and monotherapy prescribing patterns and sequencing may help optimize treatment outcomes.

This study aimed to identify overall physician-reported prescribing patterns and reasons surrounding current treatment practice for RA in the United States. It examined the use of TNFi vs. nonTNFi at first use targeted therapy, the use of first use targeted monotherapy vs. combination therapy, the prevalence of TNFi cycling vs. MOA switching at second use targeted therapy, and the patient and physician factors associated with each of these treatment choices.

Methods

Analyses were conducted using data collected between Q2 and Q3 2016 from the Adelphi RA Disease Specific Programme (DSP). The DSP is a cross-sectional, single point in time survey of United States rheumatologists and their adult patients with RA. A description of the methodology has been previously published and validated [15]. The DSP includes a number of checks to minimize missing data and ensure that the data collected are accurate. Rheumatologists were identified via publicly available lists, and a geographically diverse sample of physicians were subsequently recruited by field-based interviewers. Rheumatologists were compensated for participating. This study was approved for exemption by the Western Institutional Review Board, under WIRB exemption criteria 45 CFR §46.101(b)(2).

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Survey

Rheumatologists with a minimum of 2 years’ experience who were seeing ≥ 10 patients with RA a month were included in the Adelphi RA DSP. Rheumatologists completed an attitudinal survey developed specifically for this study and provided information (historical and/or at time of survey) via paper Patient Record Forms (PRF) for the next 10–15 consecutive eligible patients with RA who visited them and who met the inclusion criteria described below. This may have included newly diagnosed as well as patients with established disease.

To identify if physicians perceived a class effect across TNFi they were asked in the attitudinal survey: “Do you believe there is a class effect with the TNFi DMARDs?” Physicians could respond: “yes, with regards to efficacy”, “yes, with regards to safety”, “yes, with regards to both efficacy and safety” or “no”. This question was intended to capture a sentiment that specific TNFi medications are more similar than different and would likely be expected to yield a general similar result as any other TNFi medication.

The PRF contained detailed questions on patient demographics and disease characteristics at the time of survey completion and at the time of first and second targeted therapy initiation, reasons for therapy choice, and general patient management. Physicians were instructed to refer to patients’ medical records to complete the PRF to reduce recall bias. To identify a patient’s disease activity, physicians were asked for their perceived disease activity at each new line of therapy: “What was the level of disease activity in this patient immediately prior to initiation of the current treatment—remission, low disease activity, active disease, very active disease or don’t know?” To identify a patient’s disease severity, physicians were asked for their perceived disease severity at the current line of therapy: “What was your overall assessment of the severity of RA in this patient based on your own definitions of the terms mild, moderate and severe immediately prior to initiation of the current treatment?” To identify a patient’s level of pain, physicians were asked: “What was your overall assessment of the pain that your patient experienced as a result of their RA immediately prior to initiation of current treatment on a scale of 1–10, where 1 is no pain and 10 is worst possible pain?” To determine if patients were at the maximum csDMARD dose physicians were asked: “Was the maximum recommended dose of the csDMARD reached before initiating the advanced therapy—yes, no or don’t know?” Finally, physicians were asked to provide reasoning for patients switching following initial TNFi therapy. The response options available related to efficacy/change in disease included: condition worsened, condition improved, primary lack of efficacy (initial non-response), secondary lack of efficacy (loss of response over time), remission not induced, remission not maintained, and lack of alleviation of pain. Although there was potential for overlap between answers, the survey allowed physicians the option to respond in terms that resonated most with their real-world clinical practice.

Patient Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of RA who were not currently involved in a clinical trial, and who were visiting a participating rheumatologist were included in the DSP. Patients currently receiving or who had previously received ≥ 1 line of targeted therapy were included in this study. Each physician was asked to document their clinical status at the time that they started each line of targeted therapy based on their manual review of patients’ medical records.

Analysis Definitions

Patients with recorded first and second use targeted therapy were analyzed in this study. The analysis aimed to further categorize patients based on the treatment approach used and treatment pathway followed.

First and Second Use Targeted Therapy

Patients were grouped based on the class of their first use targeted therapy as either TNFi bDMARD (TNFi: etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab), nonTNFi bDMARD (nonTNFi: abatacept, rituximab, and tocilizumab), or tsDMARD (i.e. tofacitinib) based on availability on the United States market at the time of this study. Second use therapy was defined as a targeted therapy (TNFi, nonTNFi or tofacitinib) that was prescribed to the patient following their first targeted therapy, alone or in combination with a csDMARD.

Monotherapy and Combination Therapy

Targeted monotherapy was defined as a targeted therapy that was not prescribed in combination with a csDMARD as classified by the physician. Targeted combination therapy was defined as a targeted therapy that was prescribed in combination with any csDMARD.

TNFi Cycling and MOA Switching

Patients who received a TNFi as both their first and second targeted therapy were defined as TNFi cyclers. Patients who received a TNFi as first use targeted therapy but a nonTNFi targeted therapy (including tofacitinib) as their second targeted therapy were defined as MOA switchers. Patients were excluded if they initiated their second targeted therapy prior to June 2006, to allow availability of nonTNFi targeted therapy into the market (which were first introduced and widely available in 2006).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed by frequency and percentage of patients falling into each category. Univariate analysis was used to compare the analysis groups for the two analyses based on patient characteristics and physician responses. Fisher’s exact tests were used to test for differences where the outcome variable was dichotomous and Pearson’s Chi squared tests for categorical variables with more than two responses. Mann–Whitney U tests were performed for continuous variables and categorical variables with ordered responses. Survival estimates for time to discontinuation of first use targeted therapy were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and were reconstructed based on historical information that the physician provided following review of medical records. While physicians would have had access to a patient’s medical records when completing the DSP, if they did not have enough information available to classify a patient as mild, moderate or severe, then they could answer ‘don’t know’. Differences between first use targeted therapy class were assessed using log-rank tests. Where statistical tests were performed, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and compared TNFi versus nonTNFi (including nonTNFi bDMARD and tofacitinib). All analyses were performed by using Stata 15.0 or later (StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

Results

First Use Targeted Therapy

The overall DSP sample included 1003 patients and 85 rheumatologists. Of these, 631 patients treated by 84 participating rheumatologists had been prescribed a first use targeted therapy for RA following csDMARD failure and were included in the analysis sample (Supplementary Fig. 1). Eight patients who had received a targeted therapy but the number of lines of treatment was unknown were excluded, as were 364 patients who were targeted therapy-naïve. First use targeted therapy with TNFi was prescribed for 535 (84.8%) patients, 53 (8.4%) were prescribed a nonTNFi, and 43 (6.8%) were prescribed tofacitinib. Overall, 95.4% of patients receiving a bDMARD or tsDMARD as first use targeted therapy had moderate-to-severe RA. Of patients receiving TNFi, non-TNFi and tofacitinib, respectively, 96.3%, 95.2% and 88.4% had moderate-to-severe RA. csDMARD prescribing alongside first use targeted therapy details were known for 577 patients, of whom 108 (18.7%) were prescribed first use monotherapy (bDMARD or tsDMARD without csDMARD) and 469 (81.3%) were prescribed combination therapy (bDMARD or tsDMARD with csDMARD). Patient demographics by class of first use targeted therapy and monotherapy compared with combination therapy are summarized in Table 1.

Potential Drivers for Targeted Therapy Selection at First Use

At initiation of first use targeted therapy, 62.9% of patients overall had moderate disease severity. More patients receiving a TNFi at first use had severe disease compared with those receiving a nonTNFi or tofacitinib (34.5% vs. 20.8% vs. 23.3%, respectively; P = 0.02) (Table 1).

The time between RA diagnosis and first use targeted therapy initiation, based on 542 patients with data available for the date of diagnosis and initiation of first use targeted therapy, was 38.3 months overall, and there was no significant difference (P = 0.40) in the time from diagnosis to first use targeted therapy between those receiving a TNFi compared with those receiving a nonTNFi or tofacitinib. Overall, around a quarter of patients (28.7%) discontinued csDMARD therapy at initiation of their first targeted therapy, and this was consistent between the TNFi and nonTNFi groups but higher for the tofacitinib group (Table 1).

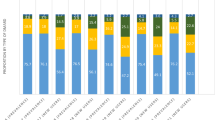

Physicians’ reasons for targeted therapy choice were known for the 422 patients who were still receiving their first targeted therapy at the time of survey completion. The top three reasons given by physicians overall for prescribing the first use targeted therapy were strong overall efficacy (79.9%), inhibition of disease progression (60.2%), and reduction in stiffness (58.5%) (Fig. 1). Physician reasoning that varied significantly between patients receiving TNFi, nonTNFi, and tofacitinib, respectively, were: maintenance of efficacy over time (48.3% vs. 67.5% vs. 31.6%; P = 0.01); allows reduction in steroid use (39.5% vs. 55.0% vs. 23.7%; P = 0.02); suitability for patients with cardiovascular risk (8.7% vs. 32.5% vs. 7.9%; P < 0.05); acceptability of method of delivery for the patient (e.g. intravenous vs. subcutaneous vs. oral administration; 19.5% vs. 27.5% vs. 39.5%; P = 0.01); and ease of product use for the patient (e.g. prefilled pen vs. syringe; 16.6% vs. 22.5% vs. 44.7%; P < 0.05) (data not shown). Interestingly, and despite RA treat-to-target recommendations encouraging switching if the patient does not achieve remission, or at least low disease activity, only 20% of physicians reported changing treatments due to lack of attaining remission.

Median time to discontinuation of the first targeted therapy was not significantly different between the classes (TNFi: 3.0 years; nonTNFi: 4.0 years; tofacitinib: median not reached; P = 0.36) (Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time to discontinuation of first targeted therapy for TNFi versus nonTNFi versus tofacitinib. TNFi, median time to discontinuation (95% confidence interval): 3 (2.5, 4). NonTNFi, median time to discontinuation (95% confidence interval): 4 (2, –). Oral tofacitinib, median time to discontinuation (95% confidence interval): – (2, –). Log rank test for equality of survivor functions: P = 0.3642. TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Targeted Monotherapy and Combination Therapy at First Use

Overall, patients received a mean (SD) of 1.56 (0.76) csDMARDs before initiation of their first targeted therapy, which was similar for patients prescribed combination therapy or monotherapy [1.54 (0.65) and 1.57 (0.77)], respectively; (P = 0.68) (Table 1). Overall, methotrexate was the most common csDMARD prescribed immediately prior to first use targeted therapy (84.5%); however, this was lower among patients receiving monotherapy vs. combination therapy (73.1% vs. 86.2%, respectively; P = 0.01). Additionally, 63.1% of patients were at the maximum csDMARD dose as reported by the physician before initiating their first targeted therapy. Overall, 27.9% of patients discontinued csDMARD therapy at initiation of first use targeted therapy, and of those still on combination therapy, only 20.0% discontinued their csDMARD for another with their first use targeted therapy. The use of concomitant medications received immediately prior to initiation of a first targeted therapy was more common in patients receiving combination therapy versus those receiving monotherapy, respectively, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (37.3% vs. 22.3%), COX-2 inhibitors (11.3% vs. 2.9%), oral steroids (continuous: 24.7% vs. 9.7%; intermittent: 27.3% vs. 17.5%), analgesics (16.0% vs. 7.8%), or csDMARDs (93.0% vs. 65.0%); all P < 0.05.

Median time to discontinuation of the first targeted therapy was not significantly different between patients receiving monotherapy versus combination therapy (2.8 years vs. 4.0 years, respectively; P = 0.35) (Fig. 3).

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for time to discontinuation of first targeted therapy for monotherapy versus combination therapy. Monotherapy, median time to discontinuation (95% confidence interval): 2.83 (2, –). Combination, median time to discontinuation (95% confidence interval): 4.0 (3, 5). Log rank test for equality of survivor functions: P = 0.3521

TNFi Cycling Versus MOA Switching at Second-Line Targeted Therapy

Overall, 163 patients from 63 physicians received a first and second targeted therapy (post June 2006). Ninety-nine patients (60.7%) were TNFi cyclers and 64 switched to a targeted therapy with a different MOA (39.3%) at second-line (i.e. MOA switchers). Patients had a mean (SD) age of 52.4 (12.7) years at the time of the switch, 74.2% were female, and 74.2% were White (Table 1).

Around half (50.9%) of patients received etanercept as first use targeted therapy; no patients were treated with biosimilars. Median (SD) duration of first use targeted therapy was similar for TNFi cyclers and MOA switchers [1.0 (1.9) vs. 1.5 (2.3), respectively; P = 0.12], but there were significant (P = 0.03) differences in the distribution of patients who persisted on their first use targeted therapy. This was driven by a lower proportion of TNFi cyclers who persisted on their first targeted therapy for 12–24 months and ≥ 24 months (25.3% and 30.3%, respectively) compared with MOA switchers (28.1% and 43.8%, respectively) (Table 1).

The mean (SD) time from diagnosis to initiation of second-line targeted therapy was 4.5 (5.1) years for TNFi cyclers and 6.2 (7.0) years for MOA switchers (P = 0.15), and at initiation of the second use targeted therapy, 93.2% of patients overall had moderate-to-severe disease, and there was no difference between TNFi cyclers and MOA switchers (P = 0.46). TNFi cycling patients and MOA switching patients had similar clinical profiles (Table 1). Of patients receiving second use targeted therapy at the time of the survey, no significant differences in disease status (P = 0.91), disease activity (P = 0.12) or mean pain (P = 0.22) were observed between the TNFi cycling and MOA switching patients. The most common targeted therapy used at second use among TNFi cyclers was adalimumab (45.5%), while for MOA switchers it was abatacept (43.8%; Table 1).

For those patients with only first use targeted therapy (n = 587), the median interquartile range time from first-line targeted therapy to survey completion was 23 (9, 48) months (data not shown). For those patients with second-use targeted therapy (n = 173), the median interquartile range time second-line targeted therapy to survey completion was 24 (9, 38) months (data not shown). Among patients with a second use targeted therapy, the second targeted therapy was initiated approximately 2 (0.5, 3) years earlier and it was approximately 3 (2, 6) years since the first targeted therapy was initiated from survey completion (data not shown).

Overall, the main reasons physicians gave for moving patients from their first TNFi to a second targeted therapy were worsening condition (46.6%), secondary lack of efficacy (loss of response over time; 41.9%), and primary lack of efficacy (no initial response; 25.7%). Reasons for switching from first to second use targeted therapy were similar regardless of whether patients cycled to another TNFi or switched to a treatment with a different MOA, with the exception of ‘patient required an advanced therapy with a different MOA (MOA switchers: 23.8%; TNFi cyclers: 1.2%; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Top 10 overall physician reasons for switching therapy following initial TNFi therapy. Categories were not mutually exclusive, and data was for overall available population. P value: TNFi versus nonTNFi (identified as nonTNFi bDMARD and tofacitinib). bDMARD biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, MOA mechanism of action, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

All 85 physicians were surveyed on their beliefs surrounding TNFi, 61 (71.8%) believed that there was some efficacy and/or safety class effect with TNFi. Of physicians who cycled their patients to another TNFi at second use, 55.8% believed there was an efficacy/safety class effect with TNFi, and of physicians who switched their patients to targeted therapy with a different MOA at second-line, 87.3% believe there was an efficacy/safety class effect with TNFi (P < 0.05) (data not shown).

Discussion

In the current study, most patients were prescribed a first use targeted combination therapy (81.3%). These results are aligned with current guidelines, which recommend combination therapy with a csDMARD and a targeted therapy in all patients with established disease who are not achieving adequate control with csDMARD monotherapy, except in patients who are clinically ineligible (i.e. with a contraindication or intolerance to all csDMARDs) [2, 3]. The percentage of patients prescribed monotherapy in this study (19%) was not prominent; however, it is slightly lower than previously reported, where a quarter to a third of patients were reported as using monotherapy at first use [14, 16]. It is important to note that estimates of bDMARD or tsDMARD monotherapy use may actually be underestimated in practice due to the prevalence of patient non-adherence with csDMARD combination therapy, which may be under recognized by rheumatologists [14, 17]. This study did not investigate patient nonadherence. Additionally, it should be noted that although current guidelines recommend that targeted therapies are used in combination with csDMARDs, many of the labels for the targeted therapies state that treatment can be given either as monotherapy or in combination with csDMARDs.

The study also demonstrated that 95.4% of patients receiving a bDMARD or tsDMARD as first use targeted therapy had moderate-to-severe RA. Our results are aligned with current RA treatment guidelines, which recommend bDMARDs or tsDMARDs for patients with moderate-to-severe RA and not those with mild disease [2, 3]. Given potential uncertainties in classifying moderate to severe disease, this nomenclature has been updated in recent years in regulatory labels to reflect moderate to severely active disease.

Other retrospective cohort studies examining the reasons for switching or discontinuing bDMARD therapy have also found that the main reasons for changing treatment were lack of efficacy and adverse events [18]. However, this study is potentially the first to investigate physician rationale around prescribing targeted therapy. The top three overall reasons given by physicians for prescribing each specific type of a first targeted therapy were strong overall efficacy, inhibition of disease progression, and reduction in stiffness. Meanwhile, the three main reasons physicians gave for switching patients from their first TNFi to a second targeted therapy were worsening condition, secondary lack of efficacy (loss of response over time), and primary lack of efficacy (no initial response). While these top three reasons were not uniquely different between the treatment groups, it was found that factors such as ease of use and method of administration could have significantly impacted a physicians’ decision about treatment choice. It should be taken into account that there might be a difference in motivation, expected efficacy and safety when switching to another TNFi due to intolerance or side effects of the first TNFi rather than a primary or secondary lack of clinical efficacy.

Patients prescribed a bDMARD at first use typically receive a TNFi, however, many will not be adequately controlled at this stage [19,20,21], and may therefore be treated with an alternative second targeted therapy. The current study found that of 163 patients who received a second targeted therapy, over half cycled (61%) to another TNFi while the remainder (39%) switched to a targeted therapy with another MOA. This is despite the fact that the majority of physicians (72%) in this study believed that there was a class effect with TNFi with regards to efficacy and/or safety, and previous studies have demonstrated better outcomes for MOA switchers than TNFi cyclers. A retrospective cohort study of 936 TNFi cyclers and 581 MOA switchers found that when switching to a second targeted therapy with a different MOA following TNFi failure, switchers were more persistent with their new therapy, had improved clinical outcomes, utilized less healthcare resources, and incurred lower costs than TNFi cyclers [10]. Further, a randomized control trial (n = 300) comparing efficacy of TNFi and nonTNFi as a second targeted treatment choice found nonTNFi therapy to be more effective in achieving a good or moderate disease activity response at 24 weeks, although the magnitude of clinical differences in disease activity as measured by the Disease Activity Score-28 erythrocyte sedimentation rate were small (0.43 units) [12]. One explanation for the large proportion of TNFi cyclers in our current study, could be due to a belief that changing molecules [e.g. changing from a fusion protein (etanercept) to a monoclonal antibody (adalimumab)] is as effective as changing to a therapy with a different MOA. It is also important to note that at second use targeted therapy, the rate of TNFi class effect was greater among physicians that switched their patients to a drug with a different MOA following failure versus those that cycled their patients to another TNFi.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The methodological strengths of this study lie in the recruitment of a geographically diverse sample of United States rheumatologists from specialty physician practices, which has previously not been covered in other work, using robust, well established data collection tools. It is important to note some limitations of the current study. Firstly, physician participants represented a convenience sample, and although they were asked to provide data for a consecutive series of patients to mitigate selection bias, no formal verification procedure was used. It is therefore not clear whether the convenience sample used is representative of the whole United States prescriber population. Also, as disease activity was based on physician perception and not composite measures of disease activity, it may be possible that disease activity was not accurately represented compared with the standards used commonly in RA clinical trials (e.g. Disease Activity Score 28 Clinical Disease Activity Index). Nevertheless, physician perception likely reflects the gestalt interpretation most relevant to a clinician when making treatment decisions. Furthermore, some patients reported as being prescribed combination therapy by their physician may be misclassified due to potential nonadherence with csDMARDs; therefore, the percentage of patients utilizing monotherapy may actually be underestimated. Additionally, by utilizing a cross-sectional survey to describe longitudinal trends, there are limitations related to the recall of certain factors by both physicians and patients, such as prior disease state and time to discontinuation. Also, the survey uses historical information and recall, which may be a significant cofounding factor to the true accuracy of the survival estimates for time to discontinuation of first use targeted therapy. It is also important to note that at the time of the survey, newer treatment options such as sarilumab and baricitinib were not commercially available. It should also be noted that while biosimilars were introduced in Europe in 2006, in the United States, they were not approved until 2015, and not available in the United States until the end of 2016 [22], meaning that the penetration of biosimilars at the time of this study in the United States market would be extremely limited, which would explain why no prescriber in this study utilized biosimilars. Finally, with this observational, cross-sectional study design, it was not possible to demonstrate cause and effect of physician reported patterns of use, behaviors, and patient profiles on real world treatment utilization patterns.

Conclusions

Most patients were prescribed a TNFi as their first targeted therapy, mainly in combination with a csDMARD. Although the majority of rheumatologists believed that there was a class-effect with TNFi, over half of patients cycled to another TNFi rather than switched to a targeted therapy with a different MOA at second use targeted therapy. The main reasons physicians gave for changing therapy were worsening condition, and primary and secondary lack of efficacy. These results suggest other factors may influence second use targeted therapy choice, and points to a need for greater understanding on the outcomes associated with subsequent treatment choices and the potential benefits of alternative MOA therapies.

References

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Carmona L, Wolfe F, Vos T, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1316–22.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(1):1–26.

Smolen JS, Landewe R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):960–77.

Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, Moreland LW, Weisman MH, Birbara CA, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):35–45.

Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, Tannenbaum H, Hua Y, Teoh LS, et al. Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1400–11.

van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Rodriguez-Valverde V, Codreanu C, Bolosiu H, Melo-Gomes J, et al. Comparison of etanercept and methotrexate, alone and combined, in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: two-year clinical and radiographic results from the TEMPO study, a double-blind, randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(4):1063–74.

Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Furst D, Weisman MH, et al. Sustained improvement over two years in physical function, structural damage, and signs and symptoms among patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1051–65.

Favalli EG, Raimondo MG, Becciolini A, Crotti C, Biggioggero M, Caporali R. The management of first-line biologic therapy failures in rheumatoid arthritis: current practice and future perspectives. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(12):1185–95.

Bonafede M, Fox KM, Watson C, Princic N, Gandra SR. Treatment patterns in the first year after initiating tumor necrosis factor blockers in real-world settings. Adv Ther. 2012;29(8):664–74.

Chastek B, Becker LK, Chen CI, Mahajan P, Curtis JR. Outcomes of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor cycling versus switching to a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug with a new mechanism of action among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ. 2017;20(5):464–73.

Wei W, Knapp K, Wang L, Chen CI, Craig GL, Ferguson K, et al. Treatment persistence and clinical outcomes of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor cycling or switching to a new mechanism of action therapy: real-world observational study of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the United States with prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. Adv Ther. 2017;34(8):1936–52.

Gottenberg JE, Brocq O, Perdriger A, Lassoued S, Berthelot JM, Wendling D, et al. Non-TNF-targeted biologic vs a second anti-TNF drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis in patients with insufficient response to a first anti-TNF drug: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1172–80.

Chastek B, Chen CI, Proudfoot C, Shinde S, Kuznik A, Wei W. Treatment persistence and healthcare costs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis changing biologics in the USA. Adv Ther. 2017;34(11):2422–35.

Engel-Nitz NM, Ogale S, Kulakodlu M. Use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: a retrospective study of monotherapy and adherence to combination therapy with non-biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Rheumatol Ther. 2015;2(2):127–39.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(11):3063–72.

Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1897–904.

Choy E, Aletaha D, Behrens F, Finckh A, Gomez-Reino J, Gottenberg JE, et al. Monotherapy with biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(5):689–97.

Rashid N, Lin AT, Aranda G, Lin KJ, Guerrero VN, Nadkarni A, et al. Rates, factors, reasons, and economic impact associated with switching in rheumatoid arthritis patients newly initiated on biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in an integrated healthcare system. J Med Econ. 2016;19(6):568–75.

Harnett J, Wiederkehr D, Gerber R, Gruben D, Koenig A, Bourret J. Real-world evaluation of TNF-inhibitor utilization in rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Econ. 2016;19(2):91–102.

Tymms K, Littlejohn G, Griffiths H, de Jager J, Bird P, Joshua F, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with rheumatic disease (rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and undifferentiated arthritis (UnA)) treated with subcutaneous TNF inhibitors. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(6):1617–23.

Cannon GW, DuVall SL, Haroldsen CL, Caplan L, Curtis JR, Michaud K, et al. Persistence and dose escalation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(10):1935–43.

Kim SC, Sarpatwari A, Landon JE, Desai RJ. Utilization and treatment costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors after the introduction of biosimilar infliximab in the U.S. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41201.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support provided by Abby Armitt, Prime, Knutsford, Cheshire, UK, was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Emma Sullivan, Jim Kershaw and Stuart Blackburn were employees of Adelphi Real World at the time of this analysis, a company that received funding for the current study from Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Jeannie Choi was an employee of and stockholder in Sanofi at the time of this analysis and is now self-employed. Susan Boklage is an employee of and stockholder in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Jeffrey Curtis is a consultant to Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved for exemption by the Western Institutional Review Board, under WIRB exemption criteria 45 CFR §46.101(b)(2):

(2) Research involving the use of educational tests (cognitive, diagnostic, aptitude, achievement), survey procedures, interview procedures or observation of public behavior, unless:

(i) Information obtained is recorded in such a manner that human subjects can be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects; and (ii) any disclosure of the human subjects’ responses outside the research could reasonably place the subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or be damaging to the subjects’ financial standing, employability, or reputation.

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability

Data are not publicly available; however, would be available on reasonable request to external parties, after request review by Adelphi Real World executive committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Digital Features

To view digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11994396.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sullivan, E., Kershaw, J., Blackburn, S. et al. Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drug Prescription Patterns for Rheumatoid Arthritis Among United States Physicians. Rheumatol Ther 7, 383–400 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00203-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-020-00203-w