Abstract

Introduction

We describe the journey to diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) from the patient perspective and examine differences in this journey by sex.

Methods

US adults aged ≥ 18 years with a self-reported AS diagnosis were recruited online through CreakyJoints, a patient support community, and ArthritisPower, a patient research registry. Respondents completed a web-based survey on sociodemographics, disease burden, and diagnosis history. Results were stratified by sex and time to diagnosis using two-sample t tests and χ2 tests, respectively, to observe differences across the groups; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 235 respondents, 174 (74.0%) were female. Mean (SD) ages of female and male respondents were 48.6 (10.6) and 53.1 (10.3) years, respectively. From the time respondents began seeking medical attention, 87 were diagnosed within ≤ 1 year, 71 in 2–9 years, and 77 after ≥ 10 years. Symptoms that led respondents to seek treatment were back pain (73.2%) and joint pain (63.8%); fatigue and difficulty sleeping were more common among respondents with longer times to diagnosis. During the diagnosis process, men with AS tended to receive quicker AS diagnosis compared with women. Overall, commonly reported initial diagnoses among respondents with longer time to AS diagnosis included back problems and psychosomatic disorders. Significantly more women reported misdiagnoses of fibromyalgia (20.7 vs. 6.6%) and psychosomatic disorders (40.8 vs. 23.0%) compared with men.

Conclusions

Diagnosis delays and misdiagnoses were common among respondents with AS. Increasing awareness about AS among referring providers may minimize diagnosis delay.

Funding

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Plain Language Summary

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a debilitating disease with a negative impact on patients’ quality of life (QOL). Because diagnosing this disease is challenging, patients often encounter diagnosis delays and misdiagnoses. We sought to understand the patient journey to receiving a diagnosis of AS from the patient perspective. We also wanted to study the differences that men and women experience in this journey.

In our study of 235 patients, 87 received a diagnosis of AS within ≤ 1 year (37%), 71 in 2–9 years (30%), and 77 after ≥ 10 years (33%). Patients started seeking medical treatment when they started experiencing AS symptoms of back pain and joint pain. Symptoms such as fatigue and difficulty sleeping were more common among patients with longer times to diagnosis. We discovered that men with AS tended to receive quicker AS diagnosis compared with women. The most common misdiagnoses received by patients with longer time to diagnosis were back problems and psychosomatic (“all in my head”) disorders. More women reported that they received misdiagnoses of fibromyalgia and psychosomatic disorders compared with men.

Our study provides insight into diagnosis delays and misdiagnoses among patients with AS. Increasing awareness about AS among clinicians may minimize diagnosis delay.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease characterized by inflammation of the sacroiliac joints, spine, and entheses [1]. Diagnosing patients with AS is often challenging due to a variety of reasons: high prevalence of back pain in the general population, slow progression of disease, lack of specific symptoms or biomarkers, high frequency of nonrheumatology consults initially sought by patients, and lack of clear guidelines for rheumatology referrals [2,3,4]. Many patients may not seek medical help due to the limited awareness of AS within the general population [5], thus precluding an early diagnosis [6]. The widely accepted modified New York criteria for AS specify radiographic sacroiliitis as a classification criterion for AS [7]; however, radiographic changes may take a number of years to develop, if they occur at all, thus complicating the detection and management of patients with possible early stages of the disease who do not yet manifest damage in the sacroiliac joints on plain films [8]. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for AS, developed in 2009, included patients with radiographic sacroiliitis as well as patients with nonradiographic sacroiliitis (e.g., sacroiliitis as detected by magnetic resonance imaging or the presence of HLA-B27 and ≥ 2 other clinical features) [9].

Although the prevalence of AS is known to be between 0.2 and 0.5% in the United States, true prevalence is unknown due to the significant delay in diagnosis and underrecognition of the disease [10]. Additionally, sex differences have been described in spondyloarthritis—women experience a longer delay in diagnosis [11, 12], even though the age of onset of AS does not vary between men and women [13, 14]. AS occurs more frequently in male than female patients, with disease onset typically occurring in the late teens through 40 years of age [15]; the average symptom duration before diagnosis has been reported to be as long as 14 years [16]. Delayed diagnosis may increase the clinical and economic burden on patients and their caregivers [6]. Understanding the diagnosis journey of patients with AS and identifying opportunities to quickly diagnose and appropriately refer patients are critical in preventing irreversible joint damage and preserving mobility.

The objectives of this study were to describe the patient journey to receiving a diagnosis of AS from the patient perspective and evaluate the differences captured between male and female patients, both overall and stratified by time between seeking medical attention and receiving a formal AS diagnosis.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

US adults aged ≥ 18 years with a self-reported diagnosis of AS were recruited through CreakyJoints (https://creakyjoints.org), an online patient support community comprising patients with arthritis and arthritis-related diseases and their caregivers, ArthritisPower (https://arthritispower.creakyjoints.org), an online patient research registry similarly comprising patients with arthritis and arthritis-related diseases, and outreach through social media; the Global Healthy Living Foundation is the parent organization of the CreakyJoints and ArthritisPower arthritis patient communities. Adult patients were primarily recruited via e-mails sent to patients included in the CreakyJoints and ArthritisPower member databases. Members use both websites for information about arthritis and social support from other members with similar disease experiences. Members of the CreakyJoints and ArthritisPower groups were asked to complete an optional online registration with self-reported demographic and health information. Members of the ArthritisPower research registry consented to participate in the registry and completed an online registration with self-reported demographic and health information. A query of the CreakyJoints and ArthritisPower member directories was performed to identify patients who self-reported having received a diagnosis of AS from their physicians. Global Healthy Living Foundation researchers scanned the membership databases to identify eligible members based on profile information that members voluntarily provided. CreakyJoints and ArthritisPower profile information contains self-reported data on age, sex, location via zip code, condition, and currently prescribed medications. Eligible patients included members aged ≥ 18 years with a self-reported diagnosis of AS. Survey questions were developed following analysis of qualitative interviews of patients with AS and clinical experts, as well as a targeted literature review. This study was reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (IRB; Salus IRB). All research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and all later amendments. All participants were required to provide verbal consent and authorization prior to participating.

Study Variables and Data Analysis

Respondents completed a web-based survey to collect self-reported patient-level information on the following: sociodemographic and treatment characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, current employment status, relationship status, annual income, and health insurance type), clinical characteristics (Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 [RAPID3] cumulative score [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], RAPID3 categorical disease activity/severity [near remission = 1–3, low = 4–6, medium = 7–12, high = 13–30] [17,18,19], current symptoms, and other health conditions), and diagnosis history (time since symptom onset, first symptom to prompt seeking healthcare, time between symptom onset and seeking medical treatment, types of healthcare providers seen, time between seeking medical attention and formal diagnosis, time since official diagnosis, and misdiagnoses). Data were stratified by sex and time between seeking medical attention and receiving a formal diagnosis of AS, with cutoffs chosen post hoc to approximate an even distribution of respondents across groups (≤ 1 year, 2–9 years, and ≥ 10 years). Survey results are presented descriptively, continuous variables are summarized using means and SDs, and categorical variables are summarized using frequencies and percentages. Survey results stratified by sex and time to AS diagnosis were analyzed using two-sample t tests and χ2 tests, respectively, to observe differences across the groups; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 1178 members in ArthritisPower and CreakyJoints with AS were contacted by e-mail. Of these, 235 responded and were included in our analysis. Among the 235 respondents diagnosed with AS, 174 (74.0%) were female, and the mean (SD) age of all respondents was 49.8 (10.7) years (Table 1). On average, male respondents were older than female respondents (mean [SD], 53.1 [10.3] vs. 48.6 [10.6] years). Respondents were predominantly white (92.8%), and almost half (48.9%) had received an undergraduate or postgraduate degree. With regard to employment, 110 respondents (46.8%) were employed full or part time, 26 (11.1%) were retired, and 89 (37.9%) were disabled. Two-thirds of respondents had private insurance, and approximately one-third had Medicare or Medicaid. Overall, 87 respondents (37.0%) received an AS diagnosis ≤ 1 year after they sought medical attention, 71 respondents (30.2%) received the diagnosis within 2–9 years, and 77 (32.8%) after ≥ 10 years. Respondents with longer times to diagnosis (≥ 10 years) tended to be older and were more likely to be white; however, these trends were not statistically significant. Nearly 80% of respondents had received biologics; 84.3% of respondents had been prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for AS, and almost 65% of respondents had received nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Significantly more women with AS were prescribed nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs compared with men (71.8 vs. 44.3%; P = 0.0002).

Overall, the mean (SD) cumulative RAPID3 score for all respondents was 15.4 (5.4), and the majority of respondents (71.9%) had high disease severity (score, 13–30), regardless of time to AS diagnosis (Supplemental Table 1); although the proportion of respondents with high disease severity appeared to be higher among respondents with a time to diagnosis of 2–9 years (76.1%) and ≥ 10 years (75.3%) compared with those with ≤ 1 year to diagnosis (65.5%), this trend was not statistically significant (P = 0.6075). At the time of survey participation, more than half of patients (62.6%) reported experiencing disease flare-up; common symptoms reported included stiffness (86.4%), fatigue (84.3%), and back pain (83.0%). Furthermore, presence of fatigue/exhaustion/tiredness, difficulty sleeping, migraine, tendon or ligament pain, and irritable bowel syndrome were increasingly more prevalent with longer time to diagnosis, whereas back pain, joint pain, and fibromyalgia were more common among respondents with shorter times to diagnosis. A significantly higher number of respondents with a longer time to diagnosis reported experiencing tendon or ligament pain (P < 0.05). With regard to sex differences—significantly more women with AS reported fatigue, back pain, difficulty sleeping, anxiety, migraine, tendon or ligament pain, foot problems, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome compared with men with AS, whereas more men with AS reported hypertension compared with women.

The cumulative percentage of respondents with AS who received a formal AS diagnosis over time from seeking medical attention, as stratified by sex, is shown in Fig. 1. Time to diagnosis was shorter among men compared with women. Overall, the mean (SD) time since symptom onset was 17.9 (12.6) years, and the mean (SD) time since receiving an official diagnosis of AS was 8.5 (9.3) years, suggesting that, on average, respondents experienced a delay in diagnosis of AS of > 9 years. Common symptoms that led respondents to initially seek medical attention were back pain (73.2%), joint pain (63.8%), and stiffness (59.1%) (Fig. 2a). Sciatica and difficulty walking were more commonly reported as symptoms that led to seeking medical attention among respondents with longer times to diagnosis. Female respondents were more likely to seek medical care due to foot problems (31.6 vs. 11.5%), whereas male respondents were more likely to seek care due to uveitis (31.1 vs. 14.9%; both P < 0.05) (Fig. 2b). More than half of respondents (57.0%) sought medical treatment within a year of symptom onset, with no differences between men and women; however, 30.2% of respondents waited > 2 years after symptom onset before seeking medical treatment.

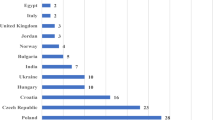

During the diagnosis process, the majority of respondents (87.2%) consulted with general practitioners or family doctors, followed by rheumatologists (65.1%) and orthopedists (26.8%); a significantly higher number of respondents with a shorter time (≤ 1 year) to diagnosis sought medical care from rheumatologists compared with those with longer times (2–9 or ≥ 10 years) to diagnosis (77.0 vs. 67.6% and 49.4%, respectively; P = 0.0009) (Fig. 3). With increasing time to diagnosis, respondents were more likely to see other nonrheumatologists including general practitioners/family doctors, sports medicine specialists, psychologists, dermatologists, podiatrists, and pediatricians. Only nine of 235 respondents (3.8%) reported that they never had a misdiagnosis. A significantly higher number of respondents with a shorter time (≤ 1 year) to diagnosis reported that they were never misdiagnosed compared with those with a longer time (2–9 or ≥ 10 years) to diagnosis (33.3% vs. 7.0 and 6.4%, respectively; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a). The most commonly reported misdiagnoses were back problems (44.3%), psychosomatic disorders (36.2%), and anxiety/depression (21.3%); a significantly higher number of respondents with a longer time to diagnosis reported receiving misdiagnoses of back pain, psychosomatic disorders, sciatica, orthopedic issues, and osteoarthritis compared with respondents with a shorter time to diagnosis (all P < 0.05) (Fig. 4a). Significantly higher proportions of women reported misdiagnoses of fibromyalgia (20.7 vs. 6.6%) and psychosomatic issues (40.8 vs. 23.0%) compared with men (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b).

Misdiagnoses received prior to official AS diagnosis among respondents with AS, stratified by (a) time between seeking medical attention and receiving formal diagnosis and (b) sex. AS ankylosing spondylitis. Respondents could have selected > 1 option. † P < 0.05 comparing respondents with time to AS diagnosis of ≤ 1 year, 2–9 years, and ≥ 10 years. ‡ P < 0.05 comparing men and women

Discussion

In this study, we described the journey to receiving a diagnosis of AS from the patient perspective by examining differences by sex and by time to diagnosis via a web-based survey. Respondents with a shorter time to diagnosis were more likely to seek medical attention due to back pain, joint pain, swollen joints, and difficulty breathing, whereas respondents with a longer time to diagnosis reported first seeking medical treatment after experiencing foot problems, neck pain, difficulty walking, uveitis, tendon or ligament pain, and pelvic pain. The manifestation of more “typical” axial AS symptoms (e.g., back pain and joint pain) may be instrumental in the timely diagnosis of the disease; respondents with these symptoms had a quicker time to diagnosis compared with respondents manifesting symptoms such as foot problems, neck pain, and pelvic pain.

Women with AS in our study were significantly more impacted by pain, fibromyalgia, and fatigue compared with men. The severity and symptoms of AS, along with pain and fatigue, were reported to be the primary contributors to impairment of patient quality of life [20], and as such, pain and fatigue management are critical in improving the physical, social, and psychological aspects of AS [21]. On the other hand, a significantly higher proportion of men with AS reported hypertension compared with women. Sex differences as observed in our analysis have been discussed in other studies, highlighting that women may manifest AS differently than men due to different immunologic [22, 23] and genetic [24, 25] responses to the disease. Additionally, enthesitis [26,27,28] and disease severity [29, 30] were significantly more pronounced in women with AS compared with men in several studies [29,30,31,32]. Compared with men with AS, women also experienced a significantly lower quality of life [26, 30] and greater delay in receiving an AS diagnosis [11, 33]. With regard to symptom presentation, one study documented that men reported experiencing inflammatory back pain more frequently than women, whereas women reported more pelvic, heel, and widespread pain during the course of the disease; at the time of diagnosis, men had more limited chest expansion and had increased occiput-to-wall distance compared with women [34]. In a 5-year prospective study of spinal radiographic progression in AS, high levels of C-reactive protein and smoking were reported as predictors of progression in men [35].

Fewer than half of respondents (37.1%) received an AS diagnosis within 1 year of seeking medical attention, and 32.8% of respondents waited more than a decade to receive the diagnosis. Overall, respondents began seeking treatment due to pain, stiffness, and fatigue, and most consulted with general practitioners for a diagnosis. During this period of diagnosis delay, patients may report feeling adrift and confused in efforts to understand and legitimize the challenges and difficulties in various aspects of their lives due to AS [5]. As this journey toward diagnosis becomes prolonged, there is an increased impact of the disease, leading to poor quality of life and overall frustration toward the providers’ inability to recognize the condition; patients may pay a “psychological price” for this journey [5]. A delay in diagnosis and subsequent treatment contribute to the economic, physical, and psychological burden on patients and their caregivers [2, 36]. Consequences of delayed diagnosis include prolonged pain, depression, stiffness, severe hip disease, and fatigue, along with the potential loss of spinal mobility and function [37,38,39,40,41].

Misdiagnoses were also common among respondents with AS in this study. Back problems (44.3%) and psychosomatic disorders (36.2%) were the most common misdiagnoses reported; interestingly, fibromyalgia was more commonly reported as a comorbid condition among patients with shorter times to diagnosis, whereas patients with longer times to diagnosis were more likely to be misdiagnosed with fibromyalgia (among other conditions). Significantly higher proportions of women than men reported misdiagnoses of psychosomatic issues and fibromyalgia in our study. Several studies have reported the coexistence of fibromyalgia in patients with AS [42, 43], and another study documented the increased prevalence of fibromyalgia among women with AS [44]. In efforts to increase the awareness and education of referring providers, such as primary care physicians and dermatologists, to reduce or prevent delayed diagnoses and misdiagnoses, various referral strategies have been suggested [45].

Earlier recognition of symptoms associated with AS may help to reduce the number of misdiagnoses, shorten the time to diagnosis of AS, and lead to improved care and health-related quality of life. Predictors and/or prognosticators of delayed diagnosis have been documented. Features such as uveitis, enthesitis, HLA-B27 expression, and metrics of disease severity, disease activity, and quality of life such as the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, and AS Quality of Life have been documented as predictors or correlates of delayed AS diagnosis [39, 46,47,48]. Upon the receipt of a diagnosis, patients with AS reported a sense of empowerment as they began to accept and understand the circumstances and seek treatment; they reported feeling relief even though they knew there was no cure for the disease [5]. One of the primary hurdles for the identification and referral of patients with AS is the high prevalence of chronic back pain within the population [2]. The median delay from time of back pain diagnosis to rheumatologist referral was approximately 10 months; after a rheumatology consultation, patients were diagnosed with AS within 1 month; predictors of quicker referral included younger age, male sex, presence of uveitis, use of prescription drugs and X-ray imaging, and primary care as the referring physician specialty [2]. Thus, increased awareness of AS and education of signs and symptoms of AS among primary care specialties may contribute to timely rheumatology referral and ultimately accurate AS diagnosis.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of limitations inherent to all patient surveys. Patient perspectives may be subject to the patients’ bias and experience. Respondents participating in the study were participating in an online community and may be more likely to take part regularly in research studies and, thus, may have had greater interest in managing their disease. Our study included a higher proportion of women than is typically observed with AS; although AS is generally a male-dominant disease [49], women are typically more active online [50]. The study relied on patients’ self-report of diagnosis of AS, which may lead to under- or overrepresentation of reporting of symptoms; clinician-reported confirmation of diagnosis was not obtained. However, the majority of respondents in this study were using biologic therapies, contributing to the validity of the diagnoses.

In conclusion, this study showed that respondents with AS sought medical help from various types of healthcare providers in their journey to obtain a diagnosis of AS and confronted diagnosis delays and misdiagnoses. Enhanced awareness of AS symptoms, particularly in nonrheumatology settings, and overcoming diagnosis obstacles may expedite referrals to rheumatologists. A timely AS diagnosis and subsequent disease management may improve disease outcomes and increase the quality of life of patients with AS.

References

Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet. 2007;369:1379–90.

Deodhar A, Mittal M, Reilly P, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis in US patients with back pain: identifying providers involved and factors associated with rheumatology referral delay. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1769–76.

Braun J, Sieper J. Early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:536–45.

Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1000–8.

Martindale J, Goodacre L. The journey to diagnosis in AS/axial SpA: the impact of delay. Musculoskelet Care. 2014;12:221–31.

Khan MA. Ankylosing spondylitis: introductory comments on its diagnosis and treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(3):3–7.

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–8.

Bennett AN, McGonagle D, O’Connor P, et al. Severity of baseline magnetic resonance imaging-evident sacroiliitis and HLA-B27 status in early inflammatory back pain predict radiographically evident ankylosing spondylitis at eight years. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3413–8.

Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, et al. The development of assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:777–83.

Reveille JD. Epidemiology of spondyloarthritis in North America. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:284–6.

Calin A, Elswood J, Rigg S, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis—an analytical review of 1500 patients: the changing pattern of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1234–8.

Jovaní V, Blasco-Blasco M, Ruiz-Cantero MT, et al. Understanding how the diagnostic delay of spondyloarthritis differs between women and men: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:174–83.

Feldtkeller E, Bruckel J, Khan MA. Scientific contributions of ankylosing spondylitis patient advocacy groups. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:239–47.

Feldtkeller E, Khan MA, van der Heijde D, et al. Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23:61–6.

Shaikh SA. Ankylosing spondylitis: recent breakthroughs in diagnosis and treatment. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2007;51:249–60.

Deodhar A, Mease PJ, Reveille JD, et al. Frequency of axial spondyloarthritis diagnosis among patients seen by United States rheumatologists for evaluation of chronic back pain. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1669–76.

Castrejon I, Pincus T, Wendling D, et al. Responsiveness of a simple RAPID-3-like index compared to disease-specific BASDAI and ASDAS indices in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000235 (eCollection 2016).

Cinar M, Yilmaz S, Cinar FI, et al. A patient-reported outcome measures-based composite index (RAPID3) for the assessment of disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1575–80.

Park SH, Choe JY, Kim SK, et al. Routine assessment of patient index data (RAPID3) and bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI) scores yield similar information in 85 Korean patients with ankylosing spondylitis seen in usual clinical care. J Clin Rheumatol. 2015;21:300–4.

Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:857–72.

Brophy S, Davies H, Dennis MS, et al. Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis: treatment should focus on pain management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:361–7.

Gracey E, Yao Y, Green B, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the Th17 signature of ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:679–83.

Huang WN, Tso TK, Kuo YC, et al. Distinct impacts of syndesmophyte formation on male and female patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:163–8.

Tsui HW, Inman RD, Paterson AD, et al. ANKH variants associated with ankylosing spondylitis: gender differences. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R513–25.

Tsui HW, Inman RD, Reveille JD, et al. Association of a TNAP haplotype with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:234–43.

Landi M, Maldonado-Ficco H, Perez-Alamino R, et al. Gender differences among patients with primary ankylosing spondylitis and spondylitis associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease in an Iberoamerican spondyloarthritis cohort. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e5652.

Shahlaee A, Mahmoudi M, Nicknam MH, et al. Gender differences in Iranian patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:285–93.

Lubrano E, Perrotta FM, Manara M, et al. The sex influence on response to tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors and remission in axial spondyloarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2018;45:195–201.

van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Zack DJ, Szumski A, et al. Female patients with ankylosing spondylitis: analysis of the impact of gender across treatment studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1221–4.

Webers C, Essers I, Ramiro S, et al. Gender-attributable differences in outcome of ankylosing spondylitis: long-term results from the Outcome in Ankylosing Spondylitis International Study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:419–28.

Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, et al. Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years’ surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:2002–8.

Kristensen LE, Karlsson JA, Englund M, et al. Presence of peripheral arthritis and male sex predicting continuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: an observational prospective cohort study from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group Register. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1362–9.

Jovani V, Blasco-Blasco M, Ruiz-Cantero MT, et al. Understanding how the diagnostic delay of spondyloarthritis differs between women and men: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:174–83.

Slobodin G, Reyhan I, Avshovich N, et al. Recently diagnosed axial spondyloarthritis: gender differences and factors related to delay in diagnosis. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:1075–80.

Deminger A, Klingberg E, Geijer M, et al. A five-year prospective study of spinal radiographic progression and its predictors in men and women with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20:162.

van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Elewaut D, et al. Referral patterns, diagnosis, and disease management of patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results of an international survey. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20:411–7.

Sorensen J, Hetland ML, All departments of rheumatology in Denmark. Diagnostic delay in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:12.

Fitzgerald G, Gallagher P, O’Sullivan C, et al. Delayed diagnosis of axial spondyloarthropathy is associated with a higher prevalence of depression. Rheumatology. 2017;56(kex062):112.

Fallahi S, Jamshidi AR. Diagnostic delay in ankylosing spondylitis: related factors and prognostic outcomes. Arch Rheumatol. 2015;31:24–30.

Seo MR, Baek HL, Yoon HH, et al. Delayed diagnosis is linked to worse outcomes and unfavourable treatment responses in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1397–405.

Zhao J, Zheng W, Zhang C, et al. Radiographic hip involvement in ankylosing spondylitis: factors associated with severe hip diseases. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:106–10.

Moltó A, Etcheto A, Gossec L, et al. Evaluation of the impact of concomitant fibromyalgia on TNF alpha blockers’ effectiveness in axial spondyloarthritis: results of a prospective, multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:533–40.

Macfarlane GJ, Barnish MS, Pathan E, et al. Co-occurrence and characteristics of patients with axial spondyloarthritis who meet criteria for fibromyalgia: results from a UK national register. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2144–50.

Almodóvar R, Carmona L, Zarco P, et al. Fibromyalgia in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: prevalence and utility of the measures of activity, function and radiological damage. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S33–9.

Danve A, Deodhar A. Screening and referral for axial spondyloarthritis—need of the hour. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:987–93.

Hajialilo M, Ghorbanihaghjo A, Khabbazi A, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis in Iran; late diagnosis and its causes. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e11798.

Ibn Yacoub Y, Amine B, Laatiris A, et al. Relationship between diagnosis delay and disease features in Moroccan patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:357–60.

Dincer U, Cakar E, Kiralp MZ, et al. Diagnosis delay in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: possible reasons and proposals for new diagnostic criteria. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:457–62.

Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:905–10.

Cooksey R, Brophy S, Husain MJ, et al. The information needs of people living with ankylosing spondylitis: a questionnaire survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:243.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of this study.

Funding

This study and the article processing charges for publication were funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by Kheng Bekdache, PhD and Eric Deutsch, PhD, CMPP of Health Interactions, Inc, was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Alexis Ogdie has received consulting fees from AbbVie, BMS, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Takeda, and Pfizer and has received grant support from Pfizer and Novartis. W. Benjamin Nowell is an employee of Global Healthy Living Foundation. Kelly Gavigan is an employee of Global Healthy Living Foundation. Shilpa Venkatachalam is an employee of Global Healthy Living Foundation. Regan Reynolds is a patient advocate affiliated with Global Healthy Living Foundation. Marie de la Cruz is an employee of ICON, which was contracted by Novartis to conduct the study. Beverly Romero is an employee of ICON, which was contracted by Novartis to conduct the study. Ethan J. Schwartz is an employee of ICON, which was contracted by Novartis to conduct the study. Emuella Flood was an employee of ICON at time of the analysis. Yujin Park is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was reviewed and approved by a central institutional review board (IRB; Salus IRB). All research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and all later amendments. All participants were required to provide verbal consent and authorization prior to participating.

Data Availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7970435.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogdie, A., Benjamin Nowell, W., Reynolds, R. et al. Real-World Patient Experience on the Path to Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis. Rheumatol Ther 6, 255–267 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-0153-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-0153-7