Abstract

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) are both chronic, inflammatory conditions that result in a substantial burden of disease and reduced quality of life for patients. Patient involvement in developing optimal disease management strategies, including defining appropriate goals, therapies, and treatment options, as well as in setting policy priorities and agendas, is key. A working group of patient organization representatives and rheumatologists explored what patients consider to be unmet needs, important treatment gaps, and future priorities in PsA and AxSpA management. Reducing pain and fatigue, and improving physical and social functioning and work productivity were identified as important treatment goals for patients. Although the major treatment target for both PsA and AxSpA is remission, with low/minimal disease activity an alternative target for patients with established or long-standing disease, the meaning of remission from the patient’s perspective needs to be explored further as it may differ considerably from the physician’s perspective. Key recommendations from the working group to tackle unmet needs included reducing time to diagnosis, increasing patient and physician disease awareness, focusing on patients’ priorities for treatment goals, and improving patient–physician communication. By addressing these key action points moving forward, the hope is that outcomes will continue to improve for patients with PsA and AxSpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and axial spondyloarthritis (AxSpA) are chronic, progressive, and often debilitating conditions with a substantial burden of disease. AxSpA, which includes both ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and non-radiographic AxSpA (nrAxSpA), is associated with progressively worsening pain and stiffness, impaired physical function, and in many patients, structural damage of the axial skeleton [1]. PsA is associated with painful, stiff, and swollen joints, functional impairment, and if untreated, progressive structural damage of affected joints [2]. The prevalence of AS ranges from 0.02% to 0.35% worldwide, whereas the prevalence of PsA ranges from 0.01% to 0.19% [3] and can be up to approximately 40% in patients with psoriasis [2]. Both conditions negatively affect quality of life, physical and social functioning, and work productivity, in addition to being associated with comorbidities and increased mortality [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Pharmacologic treatment options for PsA and AxSpA include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as first-line treatment [10,11,12,13]. Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) are recommended as second-line treatment for PsA; other options include biologic therapies, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapies (for PsA, nrAxSpA, and AS), anti-IL-17 therapy (for PsA and AS), and anti-IL-12/23 therapy (for PsA) [10,11,12,13].

Although the introduction of biologic therapies has vastly improved clinical outcomes in patients with PsA and AxSpA, patient surveys indicate that many patients are still not receiving optimal treatment for their condition [14,15,16]. Survey data collected by the National Psoriasis Foundation in the USA indicate that 45.5% of 1712 respondents with PsA expressed dissatisfaction with current therapies [14]. From the 2012 Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) survey, 59% of patients with self-reported PsA were not receiving any systemic treatment for their PsA and were either on topical therapy only or receiving no treatment. Moreover, 46% of 1209 patients who had ever used oral therapies or biologic agents felt that using currently available therapies can be worse than the condition itself, and the majority of patients (85%) indicated that better therapies are needed [15]. Indeed, a number of other limitations have been identified with anti-TNF therapies in the literature, which apply to both PsA and AxSpA, including the relatively high proportion of patients who do not respond well to these treatments and their failure to induce long-lasting remission [17].

A treat-to-target (T2T) approach to therapy is defined by physicians aiming for specific, defined targets, and adjusting treatment accordingly until these targets are achieved. Adopting this approach in PsA and AxSpA may aid the definition, measurement, and achievement of treatment success. A T2T approach has proven successful in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [18], and with treatment advances now making such a strategy feasible in PsA and AxSpA, T2T recommendations in spondyloarthritis have been published by an international task force [19]. These recommendations inform rheumatologists, other healthcare professionals, and patients about strategies to reach optimal outcomes based on evidence and expert opinion. The effectiveness of a T2T approach has already been demonstrated in PsA [20] and is highlighted in both the European League Against Rheumatic Diseases (EULAR) recommendations for the management of PsA [10] and the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis [13].

As the impact of both PsA and AxSpA for patients is far-reaching, beyond simply musculoskeletal symptoms that are often the primary focus of most rheumatology guidelines, a patient-centered approach is imperative when developing recommendations or choosing suitable treatment targets [21].

Patient involvement in decision-making is recognized as important in PsA and AxSpA [19]. In the T2T recommendations, the first overarching principle emphasizes that the treatment target must be based on a shared decision between the patient and the rheumatologist [19], which, to be implemented, requires effective communication between patients and physicians. This sentiment is also reflected in the fourth principle of the recent 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis [13]. Although most potential treatment targets take into account the patient perspective through the inclusion of patient-reported outcomes, few patients have been involved in the development or setting of these targets to date.

Two roundtable discussions attended by representatives from 14 different patient advocacy groups from France, Ireland, Italy, Russia, Switzerland, Spain, and the UK alongside two expert physicians in rheumatology from The Netherlands and the UK, were held in February 2016. One meeting focused on PsA, while the other centered on AxSpA. Patient advocacy groups from across Europe were invited to participate, with the aim of gathering a broad range of perspectives from throughout the region. The two physicians were selected on the basis of their knowledge and expertise regarding the patient perspective in spondyloarthritis.

Both meetings took the format of a traditional roundtable discussion, with short presentations followed by free discussion. Presentations were themed on the burden of disease and on treatment targets from the perspectives of the physician and patient. The objectives of both meetings were to explore what patients consider to be important treatment targets, what they perceive as unmet needs, and whether patient-defined treatment goals were consistent with priority outcomes from the physicians’ perspective. Subsequently, a further virtual meeting was held involving attendees from both the PsA and AxSpA roundtable discussions, in order to consolidate the main outcomes of the two meetings. Outcomes were analyzed thematically, with no formal method of gathering consensus.

This discussion paper summarizes the key findings and proposals identified by the working group. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Key Findings and Proposals

From the roundtable discussions, it was clear that the challenges faced and the perceived unmet needs by patients differed from country to country, particularly regarding access to treatments and appointments with physicians. However, the following general recommendations were agreed to be important future priorities for disease management from a global patient perspective.

Reducing Time to Diagnosis

The length of diagnostic delay can still be considerable in both AxSpA and PsA. For AS, the gap between disease onset and diagnosis has been reported to range from 5 to 8 years [22]; however, some studies report an even longer delay [23]. For PsA, an average delay in diagnosis of 5 years was reported in the MAPP study [7]. Although data from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry suggest distinct improvements in time from symptom onset to diagnosis in both PsA and AxSpA over the last two decades [24], such changes were not seen in a recent UK study [25] and therefore require further investigation in future studies.

Diagnostic delay presents a major concern for disease management in both PsA and AxSpA. There is some evidence to suggest that earlier treatment in the disease course is associated with better outcomes [26,27,28] and, conversely, when diagnosis is delayed, clinical outcomes are negatively affected [29, 30]. In AS, a study of 334 patients demonstrated that a delay of more than 10 years before starting anti-TNF therapy resulted in an increase in the likelihood of structural damage, compared with those who had a delay in treatment of at most 10 years [31]. In PsA, even a delay of more than 6 months has been found to contribute to poor radiographic and functional outcomes for patients with PsA [29].

In light of such findings, recommendations for the management of PsA state that early treatment should be a priority [32]. Additionally, ASAS-endorsed recommendations have been developed to aid the early referral of patients with a high suspicion of AxSpA to rheumatologists [22], which is often the rate-limiting step in timely diagnosis. One study found a median delay from first record of back pain (in a non-rheumatology setting) to referral to a rheumatologist of about 10 months; however, the time to AS diagnosis following referral was only 1 month [33].

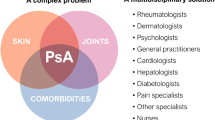

Identifying patients with suspected PsA or AxSpA can be challenging. Often, patients with PsA will either be misdiagnosed with other similar rheumatic diseases, or remain undiagnosed while showing symptoms of psoriasis [34, 35]. In a study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis in dermatology clinics, only 15% of the 20.6% patients identified as having PsA had been diagnosed previously [36]. Furthermore, 87.1% of dermatologists and 85% of rheumatologists participating in the MAPP study acknowledged that a failure to connect skin and joint symptoms leads to PsA being underdiagnosed [14].

Musculoskeletal complaints can account for up to 20% of all consultations in primary care [37]; therefore, it can often be difficult for general practitioners to identify patients with suspected inflammatory rheumatic disorders. Indeed, AxSpA only accounts for around 5% of cases of chronic back pain [38], which also increases the difficulty in deciphering which patients require referral to a rheumatologist [39]. In AxSpA, the early differentiation of inflammatory versus mechanical back pain is important because of the major differences in their management and treatment [40]. As such, a number of criteria have been proposed to clinically differentiate inflammatory from mechanical back pain. The Inflammatory Back Pain (IBP) Experts’ Criteria are robust, easy to apply, and have been validated in the international ASAS study on new classification criteria for AxSpA [41]. Therefore, these criteria, where at least four of five of the following parameters are present: (1) age at onset no greater than 40 years; (2) insidious onset; (3) improvement with exercise; (4) no improvement with rest; and (5) pain at night (with improvement upon getting up), are recommended for defining IBP in the ASAS-endorsed recommendations for early referral [21]. Whether these recommendations will prove useful for different non-rheumatic referring specialists has yet to be demonstrated.

Increasing Knowledge and Awareness for Patients and Physicians

Increasing disease awareness and education at the level of both the patient experiencing and physician treating back and/or joint pain may help facilitate early identification and referral of patients with spondyloarthritis. The working group agreed that disease education initiatives focusing on patients with suspected PsA or AxSpA, particularly targeting new (or inexperienced) patients, as well as provision of peer-to-peer support services, are needed to reduce patient delay in seeking a diagnosis. Implementing public awareness programs and increasing spondyloarthritis-focused Internet and website information may also help in this respect [42]. Moreover, enhancing general practitioners’ and other healthcare professionals’ knowledge and awareness about the heterogeneous clinical presentation of PsA and AxSpA through professional education programs, self-administered questionnaires, and referral guidelines is also crucial [42,43,44].

There is some evidence to suggest that implementation of such initiatives can have a positive impact on reducing diagnostic delay. A recent prospective, multicenter controlled study demonstrated that after specific spondyloarthritis-aimed training, a general practitioner’s consideration to refer patients with symptoms of axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis increased by more than 40% [43]. As discussed above, data from the DANBIO registry also suggest marked improvements in the time from symptom onset to diagnosis over recent years [24]. Furthermore, data from two large UK centers show that reported new cases of AS increased by 51% between 2009 and 2013 versus the preceding 5 years [25].

Disease education and awareness campaigns can also have a positive influence on patient expectations, satisfaction, treatment choices, and thus overall treatment success [44]. By physicians having an active discussion with patients, informing them of possible treatment targets and therapeutic options, including their respective benefit-to-risk ratios, patients can participate effectively in treatment decisions, leading to improved patient satisfaction and clinical outcomes [10, 13, 19, 45]. Indeed, patient involvement in medical decisions is associated with both patient satisfaction and level of information received, thereby promoting the idea that patient education can aid shared decision-making, a cornerstone in the management of rheumatic diseases [46, 47]. Interestingly, there are differences in the level of importance attributed to different aspects of the office consultation between patients and dermatologists [48]. Patients with psoriasis rate communicative aspects of the consultation, such as conveying details of treatment options or side effects of treatment, consistently higher than dermatologists do [48]. Disease education is a prominent requisite for patients, particularly being provided with information on etiology, trigger factors, and treatment [48].

Nevertheless, in an Italian study focusing on quality of life and unmet needs in patients with spondyloarthritis following the introduction of biologic therapies, although 98% of the study participants agreed that their condition had been explained to them in understandable terms by a general practitioner, approximately 60% reported a requirement for further information and 37.1% felt unsatisfied with the level of information provided during treatment [49]. As part of a project launched by the National Ankylosing Spondylitis Society (NASS) aiming to develop recommendations for improving care for AS patients in the UK, healthcare service utilization was examined [50]. The authors found that only 14.6% of patients had ever attended a disease education session; furthermore, only 12.4% of patients had been invited to attend a patient education program. Of those patients who had attended an education session, 99.1% found them “very useful” or “quite useful”, as defined by a questionnaire [50]. This result supports the concept that patient education is deemed important by the patients themselves, and that more needs to be done to ensure that patients are offered appropriate education.

In a questionnaire designed to identify the educational needs of individuals with AS, patients reported low rates of utilization of written and electronic materials due to not wanting or needing further information; however, the same cohort desired easier access to specialists to answer specific queries [16]. Thus, the results from this survey may suggest a need for more personalized information rather than generic information surrounding disease awareness. In another survey, 68.3% of patients with PsA (N = 105) expressed a need for more information on their condition and over half of the participants were interested in attending educational talks [47]. To this end, EULAR has recently published evidence-based recommendations for patient education to aid the delivery of education across Europe [51]. However, with only ten studies including patients with PsA and AxSpA available to guide these recommendations, further studies are urgently required.

Focusing on Patients’ Priorities for Treatment Goals

In order to improve treatment satisfaction, it is imperative to understand the patient’s priorities when it comes to treatment [10, 13]. From the roundtable discussions, a number of key priorities for treatment were highlighted.

Control of pain emerged as one of the dominant treatment goals for patients with PsA and AxSpA, as it was noted that management of pain often leads to improvement in overall quality of life. Pain is the symptom that is experienced most often in patients with rheumatic disorders [52] and is the most common reason patients with inflammatory arthritis see a rheumatologist [53]. In fact, the American College of Rheumatology Pain Management Task Force stated that pain may be the most important patient-reported outcome in rheumatology [52]. In the NOR-DMARD registry, approximately 88.5% and 88.2% of patients with PsA and AS, respectively, rated pain as among the top three priorities for improvement and over half of patients rated pain as first priority [54]. Similarly, in the patient-derived Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire and the ASAS Health Index, pain was identified as having the highest importance for patients [55, 56].

Other high priorities for patients include fatigue and maintenance of normal social and physical functioning. Indeed, the 2016 OMERACT-endorsed PsA core domain set for measurement in PsA clinical trials, which was developed with significant patient input, now includes both fatigue and social participation as more than 70% of patients reported these as important domains to be considered in PsA clinical trials [57]. Although fatigue levels are high in both PsA [58] and AxSpA [59], it can often be hard to manage because of its multifactorial etiology. Studies have indicated that fatigue is mostly associated with disease-related factors, such as disease activity and function, but also with patient-related factors, such as mental health and psychological distress [58,59,60,61,62]. To this end, psychological interventions, such as information on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), may prove beneficial for the management of fatigue in rheumatic disorders [63].

Decreasing work impairment was also a key priority for patients. The impact of PsA and AxSpA on work productivity can be severe; an Italian survey sponsored by the National Association of Rheumatic Patients (ANMAR) revealed that over a third of patients with spondyloarthritis felt limited by their condition in their career progression and personal development [64]. In a large Swedish study of patients with spondyloarthritis, 45% reported reduced work productivity, with a mean reduction of 20% [65]. Decreased work productivity was associated with worse quality of life, disease activity, physical function, and anxiety. Impaired ability to work also has obvious financial implications [62].

Although not a main focus of discussions, patient organization representatives emphasized the additional burden imposed by psoriasis on patients’ social lives and interactions [55, 66, 67]. Indeed, during validation of the PsAID questionnaire, skin problems were among the most important domains for patients with PsA, with many experiencing feelings of shame due to physical appearance [55]. The impact of psoriasis on the level of treatment satisfaction was also highlighted by patients with PsA [68]. To this end, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis indicated that treating to a more stringent target than the widely used PASI 75 may yield more substantial improvements in quality of life [67]. From the physicians’ perspective, clear or almost clear skin (PASI 90–100) is both a desirable and a feasible treatment target.

A major treatment target for spondyloarthritis is remission, with low/minimal disease activity an alternative target for patients with established or long-standing disease [19]. However, the meaning of remission from the patient’s perspective needs to be explored further as it may differ considerably from the physician’s perspective. In a recent study based on nine focus-group discussions throughout Europe, patients with RA characterized remission as decreased daily impact of their condition and the feeling of return to normality [69]. In PsA, a consensus has yet to be reached on the definitions of remission or low disease activity [70, 71]; until these are agreed upon and universally accepted, it will be difficult to implement such targets in clinical practice.

Overall, it is evident that patient-reported priorities warrant further attention when setting or developing treatment goals, which has important implications for treating physicians. A disconnect between the treatment priorities of healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients was a key topic of discussion throughout the roundtable meeting. Concern was expressed over the apparent disparity between physicians’ treatment goals for patients, which focus on validated assessment measures, and patients’ priorities for treatment, which focus on the impact on quality of life and maintenance of normal social and physical functioning. In light of these issues, attendees felt that practical questions regarding function and participation in daily activities were more relevant than measurement of targets. Often patients wish to discuss the personal, individual implications of their condition with their physicians, asking questions such as how they can participate fully in society or perform daily tasks. Attendees of the roundtable discussions felt that their condition, and their treatment target, should be assessed or chosen on a more practical, and again individual, basis.

Improving Communication Between Patients and Physicians

The divergent opinions on treatment priorities and disease status between the patient and the physician [72,73,74,75] highlight the need to improve communication and patient–physician interactions. Indeed, patients report wanting “to be understood as the whole person, not just the disease”. Furthermore, they are more likely to follow medication regimens if they share their physicians’ belief about causes of health outcomes [76].

Communicating their concerns and treatment goals effectively to their physician is a common issue for patients with PsA and AxSpA, particularly if they relate to their emotional/personal life and the psychological impact of the disease. For example, patients may be reluctant or too embarrassed to broach personal topics with an HCP. A similar issue has been reported for RA, where only 39% of patients who answered a questionnaire relating to personal relationships felt comfortable discussing such topics with an HCP [77]. Furthermore, a patient’s trepidation to disclose information regarding their wellbeing may prevent them from asking for further psychological help. Indeed, a lack of psychological support was reported by 37.6% of 105 patients with PsA, with 40.6% of patients expressing a need for social support and 29.3% expressing a need for counselling [48]. Visit length and time for social conversation play an important role in patient satisfaction [48] and, although beyond the scope of this article, short appointment duration is one of the key barriers in the HCP–patient relationship. The utilization of specialist nurses in patient care and management may help in this respect, as reflected in recent EULAR recommendations [78]. Some additional suggestions for improving patient–physician communication are captured in Tables 1 and 2.

Discussion

The present discussion group of patient organization representatives and rheumatologists explored what patients with PsA and AxSpA consider to be important treatment targets and unmet needs. Key priorities comprised reducing time to diagnosis, increasing patient and physician disease knowledge and awareness, focusing on patients’ priorities for treatment goals, and improving patient–physician communication. Reducing pain and fatigue, and improving physical and social functioning and work productivity were identified as important treatment goals for patients.

Regarding therapeutic strategies, there is still a requirement for more T2T strategy trials in PsA to provide further supporting evidence for this approach alongside the tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA) trial [20]. Although a similar strategy trial has commenced in AS (Tight Control in Spondyloarthritis [TICOSpA]; NCT03043846), there is currently no evidence for this approach in this condition. Optimal targets and treatment regimens for the T2T approach need to be based on evidence and further research is therefore required to decipher them; however, their selection must have appropriate patient involvement. Indeed, including patient perspectives and priorities in PsA and AxSpA disease management strategies is imperative to help meet patient expectations and improve satisfaction with treatment choices and strategies, ultimately improving patients’ long-term quality of life.

The current article is subject to some limitations. The outcomes presented are based on the opinions of individuals and may not necessarily be representative of the opinions of all patients with PsA or AxSpA. Nevertheless, attendees were invited from a variety of different patient advocacy groups to ensure that a wide range of opinions were collected. No formal method for gathering consensus was employed in the current article, with the key discussion topics being analyzed thematically. It is important, however, to acknowledge the added value of collecting qualitative information: gaining insights into patients’ thoughts and experiences can help ascertain potential avenues of investigation in larger quantitative studies [79]. Large-scale surveys would be required to obtain a wider perspective from patients and physicians and allow a more quantitative analysis of the themes described herein. Finally, the purpose of this article was not to provide a systematic review of the literature and it should not be considered as such.

Conclusions

It is important to widen our current approach to disease management from the traditional focus on physical or biologic aspects of the disease and illness to a more holistic, all-encompassing approach. This will include assessing the detrimental social and economic impact of the disease for an individual and incorporating this knowledge in the treatment decision-making process. Building a strong relationship and mutual respect between physicians and patients is imperative; this can be achieved through improved communication, which would also facilitate the joint decision-making process regarding treatment options. Personalization of treatment to individual needs is a long-term goal in disease management worldwide but requires an expanded evidence base to support its universal adoption in clinical practice.

References

Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, Boonen A, Zink A. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl 3):iii8–18.

Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, Clegg DO, Nash P. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii14–7.

Stolwijk C, van Onna M, Boonen A, van Tubergen A. Global prevalence of spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(9):1320–31.

Ali Y, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Improved survival in psoriatic arthritis with calendar time. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2708–14.

Bakland G, Gran JT, Nossent JC. Increased mortality in ankylosing spondylitis is related to disease activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1921–5.

Boonen A, van der Linden SM. The burden of ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2006;78:4–11.

Kavanaugh A, Helliwell P, Ritchlin CT. Psoriatic arthritis and burden of disease: patient perspectives from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic arthritis (MAPP) survey. Rheumatol Ther. 2016;3(1):91–102.

Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA, Carvalho AF, Hyphantis T. Health-related quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(6):857–72.

Tezel N, Yilmaz Tasdelen O, Bodur J, et al. Is the health-related quality of life and functional status of patients with psoriatic arthritis worse than that of patients with psoriasis alone? Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;18(1):63–9.

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:499–510.

Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–71.

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(2):282–98.

van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewe R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770.

Armstrong AW, Robertson AD, Wu J, Schupp C, Lebwohl MG. Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys, 2003–2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1180–5.

Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):871–81.

Cooksey R, Brophy S, Husain MJ, Irvine E, Davies H, Siebert S. The information needs of people living with ankylosing spondylitis: a questionnaire survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:243.

Dougados M, Baeten D. Spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2127–37.

Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3–15.

Smolen JS, Braun J, Dougados M, et al. Treating spondyloarthritis, including ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:6–16.

Coates LC, Moverley AR, McParland L, et al. Effect of tight control of inflammation in early psoriatic arthritis (TICOPA): a UK multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10012):2489–98.

Betteridge N, Boehncke WH, Bundy C, Gossec L, Gratacós J, Augustin M. Promoting patient-centred care in psoriatic arthritis: a multidisciplinary European perspective on improving the patient experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(4):576–85.

Poddubnyy D, van Tubergen A, Landewé R, Sieper J, van der Heijde D. Development of an ASAS-endorsed recommendation for the early referral of patients with a suspicion of axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(8):1483–7.

Feldtkeller E, Khan MA, van der Heijde D, van der Linden S, Braun J. Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23(2):61–6.

Sørensen J, Hetland ML. Diagnostic delay in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: results from the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(3):e12.

Sykes MP, Doll H, Sengupta R, et al. Delay to diagnosis in axial spondyloarthritis: are we improving in the UK? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(12):2283–4.

Gladman DD, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Cook RJ. Do patients with psoriatic arthritis who present early fare better than those presenting later in the disease? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(12):2152–4.

Rudwaleit M, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, Sieper J. Prediction of a major clinical response (BASDAI 50) to tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):665–70.

Rudwaleit M, Khan MA, Sieper J. The challenge of diagnosis and classification in early ankylosing spondylitis: do we need new criteria? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1000–8.

Tillet W, Jadon D, Shaddick G, et al. Smoking and delay to diagnosis are associated with poorer functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(8):1358–61.

Haroon M, Gallagher P, Fitzgerald O. Diagnostic delay of more than 6 months contributes to poor radiographic and functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1045–50.

Haroon N, Inman RD, Learn TJ, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(10):2645–54.

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Caujoux-Viala C, et al. European League Against Rheumatism recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):4–12.

Deodhar A, Mittal M, Reilly P, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis diagnosis in US patients with back pain: identifying providers involved and factors associated with rheumatology referral delay. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(7):1769–76.

Helliwell P, Taylor W. Classification and diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii3–8.

Mease P, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs. 2014;74(4):423–41.

Reich K, Krüger K, Mössner R, Augustin M. Epidemiology and clinical pattern of psoriatic arthritis in Germany: a prospective interdisciplinary epidemiological study of 1511 patients with plaque-type psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160(5):1040–7.

Jordan K, Clarke AM, Symmons DP, et al. Measuring disease prevalence: a comparison of musculoskeletal disease using four general practice consultation databases. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(534):7–14.

Rudwaleit M. Spondyloarthropathies: identifying axial SpA in young adults with chronic back pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):378–80.

Underwood R, Dawes P. Inflammatory back pain in primary care. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34(11):1074–7.

Harris C, Gurden S, Martindale J, Jeffries C. Differentiating inflammatory and mechanical back pain—challenge your decision making. https://www.axialspabackinfocus.co.uk/media/4409/ibp-module-booklet-1_oct-2016.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2017.

Sieper J, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: a real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):784–8.

Villeneuve E, Nam JL, Bell MJ, et al. A systematic literature review of strategies promoting early referral and reducing delays in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(1):13–22.

van Onna M, Gorter S, Maiburg B, Waagenaar G, van Tubergen A. Education improves referral of patients suspected of having spondyloarthritis by general practitioners: a study with unannounced standardised patients in daily practice. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e000152.

Helliwell P, Coates L, Chandran V, et al. Qualifying unmet needs and improving standards of care in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(12):1759–66.

Suarez-Almazor ME. Patient–physician communication. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(2):91–5.

Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Mowinckel P, Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Finset A. Rheumatology care: involvement in medical decisions, received information, satisfaction with care, and unmet health care needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(3):394–401.

Leung YY, Tam LS, Lee KW, Leung MH, Kun EW, Li EK. Involvement, satisfaction and unmet health care needs in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(1):53–6.

Giglio MD, Gisondi P, Girolomoni G. The expectations of patients with psoriasis during an office consultation. In: Clinical dermatology. http://www.clinicaldermatology.eu/materiale_cic/631_1_1/5719_expectations/article.htm. Accessed 16 June 2016.

Giacomelli R, Gorla R, Trotta F, et al. Quality of life and unmet needs in patients with inflammatory arthropathies: results from the multicentre, observational RAPSODIA study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(5):792–7.

Hamilton L, Gilbert A, Skerrett J, Dickinson S, Gaffney K. Services for people with ankylosing spondylitis in the UK—a survey of rheumatologists and patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50(11):1991–8.

Zangi HA, Ndosi M, Adams J, et al. EULAR recommendations for patient education for people with inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):954–62.

American College of Rheumatology Pain Management Task Force. Report of the American College of Rheumatology pain management task force. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(5):590–9.

Lee YC. Effect and treatment of chronic pain in inflammatory arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(1):300.

Heiberg T, Lie E, van der Heijde D, Kvien TK. Sleep problems are of higher priority for improvement for patients with ankylosing spondylitis than for patients with other inflammatory arthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(5):872–3.

Gossec L, de Wit M, Kiltz U, et al. A patient-derived and patient-reported outcome measure for assessing psoriatic arthritis: elaboration and preliminary validation of the Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease (PsAID) questionnaire, a 13-country EULAR initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1012–9.

Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Boonen A, Braun J. The ASAS Health Index (ASAS HI)—a new tool to assess the health status of patients with spondyloarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(5 Suppl 85):S-105–8.

Orbai AM, de Wit M, Mease P, et al. International patient and physician consensus on a psoriatic arthritis core outcome set for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;76(4):673–80.

Gudu T, Etcheto A, de Wit M, et al. Fatigue in psoriatic arthritis—a cross-sectional study of 246 patients from 13 countries. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(4):439–43.

Gossec L, Dougados M, D’Agostino MA, Fautrel B. Fatigue in early axial spondyloarthritis. Results from the French DESIR cohort. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(4):427–31.

Husted JA, Tom BD, Schentag CT, Farewell VT, Gladman DD. Occurrence and correlates of fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(10):1553–8.

López-Medina C, Schiotis RE, Font-Ugalde P, et al. Assessment of fatigue in spondyloarthritis and its association with disease activity. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(4):751–7.

Dagfinrud H, Vollestad NK, Loge JH, Kvien TK, Mengshoel AM. Fatigue in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a comparison with the general population and associations with clinical and self-reported measures. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(1):5–11.

Davies H, Brophy S, Dennis M, Cooksey R, Irvine E, Siebert S. Patient perspectives of managing fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis, and views on potential interventions: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:163.

Ramonda R, Marchesoni A, Carletto A, et al. Patient-reported impact of spondyloarthritis on work disability and working life: the ATLANTIS survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:78.

Haglund E, Bremander A, Bergman S, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF. Work productivity in a population-based cohort of patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(9):1708–14.

Dubertret L, Mrowietz U, Ranki A, et al. European patient perspectives on the impact of psoriasis: the EUROPSO patient membership survey. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(4):729–36.

Puig L, Thom H, Mollon P, et al. Clear or almost clear skin improves the quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):213–20.

Furst DE, Tran M, Sullivan E, et al. Misalignment between physicians and patient satisfaction with psoriatic arthritis disease control. Clin Rheumatol. 2017. doi:10.1007/s10067-017-3578-9.

van Tuyl LH, Hewlett S, Sadlonova M, et al. The patient perspective on remission in rheumatoid arthritis: ‘You’ve got limits, but you’re back to being you again’. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1004–10.

Helliwell PS, Coates LC. The definition of remission in psoriatic arthritis: can this be accurate without assessment of multiple domains? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(12):e66.

Sieper J. How to define remission in ankylosing spondylitis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(Suppl 2):i93–5.

Frantsve LM, Kerns RD. Patient–provider interactions in the management of chronic pain: current findings within the context of shared medical decision making. Pain Med. 2007;8(1):25–35.

Haugli L, Strand E, Finset A. How do patients with rheumatic disease experience their relationship with their doctors? A qualitative study of experiences of stress and support in the doctor–patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52(2):169–74.

Desthieux C, Molto A, Granger B, Saraux A, Fautrel B, Gossec L. Patient-physician discordance in global assessment in early spondyloarthritis and its change over time: the DESIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1661–6.

Desthieux C, Granger B, Balanescu AR, et al. Determinants of patient-physician discordance in global assessment in psoriatic arthritis: a multicenter European study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016. doi:10.1002/acr.23172.

Christensen AJ, Howren MB, Hillis SL, et al. Patient and physician beliefs about control over health: association of symmetrical beliefs with medication regimen adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):397–402.

Hill J, Bird H, Thorpe R. Effects of rheumatoid arthritis on sexual activity and relationships. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(2):280–6.

van Eijk-Hustings Y, van Tubergen A, Boström C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the role of the nurse in the management of chronic inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):13–9.

Sutton J. Qualitative research: data collection, analysis, and management. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):226–31.

Acknowledgements

Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland provided funding for the roundtable discussion and the article processing fees. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. We would like to thank Igor Steinzeig, Society of Patients with Psoriasis, Russia; Celia Marin, EUROPSO, Spain; Michelle Dolan, Irish Skin Foundation, Ireland; Pierre Charle, France Psoriasis, France; Renato Saviani, ATMaR Prato, Italy; Sara Severoni, ANMAR Italia, Italy; Pedro Plazuelo, CEADE, Spain; Pierre Faugère, AFLAR Association, France; Sally Dickinson, NASS, UK; and all patient organization representatives who also participated in the roundtable discussions. We would also like to thank Sanja Njegic, Head Patient Advocacy and Relations, Region Europe; Louise Huneault, Manager, Patient Relations, Global Communications and Advocacy; Emilie Prazakova, Patient Relations Manager, Region Europe; Angels Costa, Patient Advocacy Manager; Susanne O’Reilly, Government and External Affairs Head; Zhanna Baskakova, Scientific Medical Project Manager; Steffen Jugl, Worldwide Director Health Economics and Outcomes Research; Matteo Lacchio, Digital and Social Media Manager; Fabienne Porchet; Paralegal, Legal and Compliance, Region Europe; Chiara Perella, Associate Regional Medical Director, Immunology and Dermatology, Region Europe; participants of the roundtable discussion from Novartis Pharma AG; and finally Kathy Redmond, Redmond Consulting, Switzerland and Professor Dominique Baeten, Academic Medical Center/University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands, who also participated. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Antonia Bowman and Molly Heitz, of Seren Communications, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare, the funding for which was provided by Novartis Pharma AG. We would also like to thank Alexey Sitalo, President of the Russian Ankylosing Spondylitis Association, for his review of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Laure Gossec has received speaking fees or honoraria from Abbott/AbbVie, BMS, Celgene, Chugai, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB; and research grants from Lilly, Pfizer, and UCB. Laura Coates has received research funding and/or honoraria from Abbvie, BMS, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Marco Garrido-Cumbrera, Ottfrid Hillmann, Raj Mahapatra, David Trigos, Petra Zajc, Luisa Weiss, and Galya Bostynets have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content: To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/F498F0605B4A92E1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garrido-Cumbrera, M., Hillmann, O., Mahapatra, R. et al. Improving the Management of Psoriatic Arthritis and Axial Spondyloarthritis: Roundtable Discussions with Healthcare Professionals and Patients. Rheumatol Ther 4, 219–231 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0066-2

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-017-0066-2