Abstract

Introduction

In recent years researchers have reported deficits in the quality of care provided to patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), including low rates of performance on quality measures. We sought to determine the influence of a quality improvement (QI) continuing education program on rheumatologists’ performance on national quality measures for RA, along with other measures aligned with National Quality Strategy priorities. Performance was assessed through baseline and post-education chart audits.

Methods

Twenty community-based rheumatologists across the United States were recruited to participate in the QI education program and chart audits. Charts were retrospectively audited before (n = 160 charts) and after (n = 160 charts) the rheumatologists participated in a series of accredited QI-focused educational activities that included private audit feedback, small-group webinars, and online- and mobile-accessible print and video activities. The charts were audited for patient demographics and the rheumatologists’ documented performance on the 6 quality measures for RA included in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). In addition, charts were abstracted for documentation of patient counseling about medication benefits/risks and adherence, lifestyle modifications, and quality of life; assessment of RA medication side effects; and assessment of RA medication adherence.

Results

Mean rates of documented performance on 4 of the 6 PQRS measures for RA were significantly higher in the post-education versus baseline charts (absolute increases ranged from 9 to 24% of patient charts). In addition, after the intervention, significantly higher mean rates were observed for patient counseling about medications and quality of life, and for assessments of medication side effects and adherence (absolute increases ranged from 9 to 40% of patient charts).

Conclusion

This pragmatic study provides preliminary evidence for the positive influence of QI-focused education in helping rheumatologists improve performance on national quality measures for RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decade, research examining the quality of care provided to patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has indicated notable deficits, including low or variable rates of guideline-directed prescription of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and vaccinations [1–5]. Evidence suggesting gaps in care led to the development of tools to monitor and improve the quality of care for patients with RA [4, 6]. Through a collaborative project that began nearly a decade ago, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) worked with the American Medical Association’s Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement to develop a set of 6 process-based quality measures for RA [6]. These measures are included in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) [7]. The RA measures comprise DMARD prescription, tuberculosis (TB) screening within 6 months prior to initiation of a new biologic medication, disease activity assessment and classification, functional status assessment, prognosis assessment and classification, and glucocorticoid management.

Designed to improve the quality, accountability, and transparency of healthcare, the PQRS program originally provided incentive payments for eligible healthcare professionals (those who received payments under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule) who met criteria for reporting quality measures. As of 2015, the program imposes increasing reimbursement penalties for eligible professionals who have not reported PQRS measure data according to CMS requirements [8].

The terminology, principles, and implementation methods of quality improvement (QI) have not historically been taught in United States undergraduate and graduate medical schools. For practicing physicians, most QI education and training programs are based in academic medical centers and large health systems [9]. In all settings, however, physicians are currently responding to new requirements for participation in QI programs and reporting quality measures for accountability and value-based payment incentives. To realize the potential for improving the quality of healthcare, continuing education may be a key strategy for addressing QI-related knowledge, attitudinal, and practice gaps. We developed and provided continuing education activities designed to support community-based rheumatologists in improving performance on PQRS quality measures for RA and additional measures for patient counseling and assessments of medication side effects and adherence, which are related to priorities of the National Quality Strategy (NQS) [10]. To assess the influence of the education, we conducted baseline and post-education chart audits and compared rates of documented performance on these measures.

Methods

The QI education program and outcomes study were approved by an independent institutional review board (Sterling IRB, Atlanta, GA; IRB ID #4534). This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Physician Recruitment and Baseline Chart Selection

Twenty community-based rheumatologists were recruited to participate in the chart audits and educational activities. Given documented rheumatology workforce shortages in the United States, we sought to sample from states with adequate numbers of rheumatologists for the study. Using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance data, we identified states with high ratios of rheumatologists to patients with arthritis (CDC data do not distinguish numbers of patients with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis). From the states with the highest ratios of rheumatologists to patients, we identified and recruited participants through internal or purchased lists of practicing rheumatologists, whom we contacted by postal mail, fax, or email. Rheumatologists were enrolled in the order of their expressed interest in the educational program and study. We aimed to recruit approximately equal numbers of rheumatologists from the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West.

The study was designed to review 160 baseline charts of adult patients (aged 18 years and older) who had a diagnosis of RA for at least 1 year (indicated by ICD-9 codes 714.0, 714.1, 714.2, or 714.81 from billing data) and at least 1 visit with the participating rheumatologist between 12/1/2012 and 11/30/2013. Administrative staff for each of the 20 rheumatologists selected an oversample of up to 12 charts that met inclusion criteria, with the goal of obtaining an average of 8 charts per rheumatologist. This number was determined partly by pragmatic considerations including the limited time commitment that the practices could devote to identifying charts and funding restrictions.

Eligible charts were selected by reviewing consecutive patients with the most recent office visits, working backward from the index date of 11/30/2013. In the baseline period, 3 practices provided fewer than the targeted 8 charts (n = 4, 6, and 7). The rheumatologists in these practices were enrolled in the educational program; thus, their charts were included in the analysis. To compensate for these practices to reach the targeted 160 charts for baseline review, we included 9 charts from 7 other practices. These practices were selected through a process that balanced the number of charts from the 4 geographical regions.

Each practice received a $500 administrative fee to reimburse costs for staff resources. This fee, which comprised a $250 resource allocation for each of the 2 chart abstraction periods (baseline and post-education), covered costs for identifying and pulling patient charts based on eligibility criteria, as well as coordinating with the chart abstractors.

Baseline Retrospective Chart Abstraction and Analysis

Charts that met inclusion criteria were retrospectively abstracted by 1 of 4 trained medical record reviewers. Paper charts were made available for review onsite, or they were copied and sent to the chart abstractors for offsite review. Electronic charts were accessed remotely or onsite based on the preference and capability of the practice. The reviewers completed their abstraction of baseline charts between December 2013 and February 2014. To assess inter-rater reliability, each reviewer compared samples of their colleague’s charts through an internal quality assurance process. The assessment was based on numbers of chart variables for which the reviewers agreed in their abstraction.

The charts were abstracted for patient demographics and the rheumatologists’ documented performance on the 6 quality measures for RA included in the 2013 and 2014 PQRS programs (Table 1). In addition, charts were abstracted for (1) documentation of patient counseling about medication benefits/risks and adherence, lifestyle modifications, and quality of life; (2) assessment of RA medication side effects; and (3) assessment of RA medication adherence. For the latter measure, charts were reviewed for whether adherence was assessed (yes or no) and for documentation of adherence status (adherent or nonadherent). These counseling and assessment measures are related to NQS priorities for ensuring that patients are engaged in their healthcare, improving communication, promoting effective prevention and treatment practices, or making care safer [10]. Through structured chart review, each rheumatologist’s performance on the measures was recorded for analysis in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM Corporation, NY, USA), version 22.

Educational Activities

After the baseline chart review, the rheumatologists participated in a series of educational activities that were accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. The first activity was an online audit-feedback session (45 min), which was presented individually to each rheumatologist by a medical chart review expert. During these sessions, each physician’s baseline rates of performance on the PQRS quality measures were presented and compared with the de-identified mean rates of the other 19 rheumatologists in the study. The sessions were designed to support participants in identifying areas for improvement, focusing especially on measures for which baseline performance rates were low. The presenter engaged the participant in discussing barriers to performing and documenting the quality measures, as well as in identifying strategies for improvement. In addition, the feedback addressed the rheumatologist’s documentation of the patient counseling measures as well as medication side effects and adherence.

Within 4 weeks of the audit-feedback activity, each rheumatologist participated in a 45-min webinar with 4 other peers in the cohort. The 5 small-group webinars were led by an expert rheumatologist who guided discussions of strategies for improving performance on RA quality measures. One of the co-authors of this article (E. Ruderman) served as faculty presenter for these webinars. The discussions addressed the evidence-based rationale for applying the quality measures in clinical practice; approaches to improving patient assessment, treatment, and management based on the measures; and strategies for appropriately documenting performance on the measures. To reinforce learning, the educational program also included a variety of online- and mobile-accessible accredited activities in an RA QI toolkit. These included a 10-page monograph that presented the evidence-based rationale for the quality measures as well as a 12-page monograph and a 30-min video addressing interprofessional approaches to achieving high standards for the quality of RA care. The 20 rheumatologists’ participation in the audit-feedback and small-group webinar activities was confirmed through roll call. For the 3 online and mobile-accessible activities, all of the rheumatologists self-reported their participation.

Post-Education Retrospective Chart Abstraction and Analyses

Six months after each rheumatologist completed the educational activities, follow-up chart audits (n = 160) were conducted according to the same methods described for the baseline reviews. In each practice, charts were identified for patients with RA who had at least 1 visit with their physician in the post-education period. The number of post-education charts was matched to each rheumatologist’s number of baseline charts. Between August and October 2014, the post-education charts were retrospectively abstracted for documentation of the PQRS quality measures and NQS-related clinical processes during the 6-month period following each rheumatologist’s completion of the educational activities.

Statistical Analysis

Using SPSS, Chi-square tests were performed to analyze the differences between baseline and post-education frequencies of chart documentation for the PQRS quality measures for RA and the additional measures for patient counseling and assessments of medication side effects and adherence. p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The 20 participating rheumatologists were located in the Northeast (n = 6), South (n = 5), Midwest (n = 4), and West (n = 5). They reported treating an average of 41 patients with RA per week. The analysis included 160 baseline charts (mean = 8 per physician; range = 4–9) and 160 post-education charts (mean = 8 per physician; range = 4–9). The comparisons of samples of charts abstracted by the 4 different reviewers indicated agreement for at least 90% of chart variables.

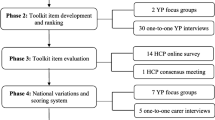

As presented in Fig. 1, there were significantly higher mean rates of performance on 4 of the 6 PQRS quality measures for RA in the post-education versus baseline charts. The absolute percentage increases for these 4 measures were as follows: tuberculosis screening before biologic DMARD therapy (24%, p < 0.001); assessment and classification of disease activity (23%, p < 0.001); assessment of functional status (9%, p = 0.01); and assessment and classification of disease prognosis (23%, p = 0.005). At baseline, 99% of patient charts indicated prescription of DMARD therapy; adherence to this measure was not significantly different in the post-education charts. For the sixth PQRS measure, documentation of a glucocorticoid management plan, only 1 patient in the post-education sample met the eligibility requirement of prolonged high-dose glucocorticoid therapy; thus, analysis for this measure was precluded.

Baseline and post-education rates of performance on PQRS quality measures for rheumatoid arthritis. For all measures other than TB screening before initiating biologic DMARD therapy, adherence rates were based on 160 baseline charts and 160 post-education charts. Analyses for TB screening were based on charts of patients who, in accordance with the quality measure, had received a first course of therapy using a biologic DMARD (n = 71 baseline charts; n = 77 post-education charts). DMARD disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, PQRS Physician Quality Reporting System, TB tuberculosis

For 2 of the 3 patient counseling measures and for assessments of side effects and medication adherence, there were significantly higher mean rates of post-education versus baseline chart documentation (Fig. 2). The absolute percentage increases for these 4 measures were as follows: counseling about medication (9%, p = 0.02); counseling about quality of life (17%, p = 0.01); assessment of medication side effects (22%, p < 0.001); and assessment of medication adherence (40%, p < 0.001). The proportion of charts indicating that patients were adherent to their medications was significantly greater in the post-education (82%) versus baseline (48%) review (p < 0.001). For counseling about lifestyle modifications, the mean percentage increase after education did not reach statistical significance (7%, p = 0.06).

Discussion

Previous reports of suboptimal performance on quality measures for RA have motivated leaders in the rheumatology community to call for programs to improve the quality of RA patient care [4, 6]. This pragmatic study provides preliminary evidence for a positive influence of accredited education on improving performance on PQRS quality measures for RA and on additional measures aligned with NQS priorities. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on QI-focused educational interventions for improving adherence to these measures. In addition, the study is unique in providing data on performance rates for the full set of PQRS RA measures among community-based rheumatologists.

With the exception of DMARD treatment, baseline rates of documented performance on the PQRS measures were low to moderate, ranging from 18% for TB screening before initiating a biologic DMARD to 74% for functional status assessment. In an analysis of the 2009 ACR Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR), Kazi et al. reported considerably higher rates of adherence to 5 quality measures among 240 rheumatology providers who submitted data for 7806 patients with RA: assessment and classification of disease activity (100%), DMARD treatment (93%), TB screening (92%), assessment of functional status (79%), and assessment and classification of disease prognosis (78%) [11]. One explanation for the higher rates of adherence reported by Kazi et al. is that the providers were self-selected members of the RCR. In addition, one of the main goals of this registry is to give providers a mechanism with which to document and report PQRS measures. In an analysis of 2005–2008 HEDIS data for more than 90,000 RA patients enrolled in Medicare managed care plans, Schmajuk et al. found that 63% of the patients had received a DMARD [5]. The authors reported that DMARD receipt varied considerably across patient groups, with the lowest rates reported for older individuals, black patients, and patients with low socioeconomic status. The study focused on health system performance, thus reflecting DMARD use across both rheumatology and primary care practices. Recently, Desai et al. reported a study involving reviews of 438 charts of RA patients in an academic medical center rheumatology practice [12]. Assessment of disease activity and functional status were documented in 29% and 75% of the charts, respectively.

Our findings indicate that a program of quality-focused education was associated with significant improvements in documented performance on 4 of the 6 PQRS measures for RA and on additional measures involving patient counseling and assessments of medication side effects and adherence. For several measures the improvements were substantial. However, post-education performance rates indicate gaps and room for improvement for most of the measures, including assessment of disease prognosis (54%), assessment of disease activity (63%), TB screening before initiating a biologic DMARD (42%), counseling for lifestyle modifications (46%) and quality of life (68%), and assessment of medication adherence (65%).

Our observations of the rheumatologists’ discussions during the audit-feedback and small-group webinar sessions may offer insight into the suboptimal post-education performance rates. These discussions addressed the barriers and challenges the physicians face in aligning their practices with national quality measures. For example, some participants commented that the methods necessary to assess and classify disease activity and prognosis are time-consuming and more appropriate for clinical trials than for office visits. Regarding the measure of TB screening, a common response from participants was that their electronic health records lack structured fields for recording this measure. Several rheumatologists commented that, despite the lack of documentation in their charts, they always screen patients for TB before initiating biologic DMARD treatment. These responses reflect the need for adaptations of electronic medical records to efficiently collect key quality and safety data in a standardized manner.

Several limitations of the study should be considered in interpreting the results. Because the endpoints were process-based quality measures, the performance of the same physicians was assessed using different patient charts in the baseline and post-education audits. This design afforded some control over participant-related extraneous variables. However, conclusions regarding the direct effect of the educational interventions are limited by the lack of a control group of rheumatologists who did not participate in the educational activities and whose charts were audited over the same time periods. An interrupted time series trial with a control group would be a stronger design for more reliably assessing whether improvements were attributable to the education rather than to secular trends.

Due to the rheumatologists’ gaps in documenting patient characteristics, especially classifications of disease activity, we were not able to determine whether patients whose charts were audited in the baseline and post-education period were matched for variables that might have influenced quality of care. Other potentially confounding factors, which may influence quality of care and, therefore, should ideally be matched across samples, include number of patient visits and patients’ income, health literacy, and comorbidities. Another limitation is that the post-education follow-up period was only 6 months. A longer follow-up may have resulted in higher post-education rates of adherence to the quality measures; in contrast, it is possible that performance on quality measures may revert to baseline over time without continual reinforcement. Finally, we were not able to determine whether the changes observed between the baseline and follow-up period related directly to improving performance on these quality measures or to better chart documentation. However, chart documentation is a critical element of the ability to assess compliance with these measures. Moreover, documentation of these measures is essential for guiding care processes, including evaluating treatment effectiveness, informing treatment decisions, and providing essential information to promote patient safety.

This pragmatic study was not designed to determine the extent to which the different educational activities influenced performance on the quality measures. The continuing education literature has indicated that conventional formats, such as didactic lectures and print media, generally do not lead to persistent changes in complex physician behaviors [13–17]. In a meta-analysis of 140 studies on chart audit and feedback as an educational intervention for healthcare professionals, the authors concluded that this method can elicit small but meaningful improvements in clinical performance [18]. The greatest improvements occur when feedback is offered by a supervisor or respected colleague and accompanied by specific goals or action plans for quality improvement. We designed the audit-feedback sessions and small-group webinars accordingly.

As suggested by Saag et al., the connection between process-based RA quality measures and patient outcomes and, therefore, the rationale for aligning clinical practice with the measures can be established with evidence from clinical trials and well-designed observational studies [4]. The development of the PQRS quality measures for RA was strongly influenced by the 2008 ACR guidelines [6]. A recent study reported that rheumatologists’ documentation of PQRS measures for disease activity assessment and functional status was not significantly associated with 2-year radiographic progression [12]. However, as acknowledged by the authors, this study was limited partly because the rates of documenting the quality measures were low and RA outcome measures were not consistently defined. New studies are thus needed to understand relationships between process-based quality measures and patient outcomes. The results of these studies will guide revisions of current quality measures and the development of new ones, including outcomes-based measures of disease activity and function [19]. Evolving value-based care delivery models may pose some barriers associated with extra time demands for performing, documenting, and reporting quality measures. Thus, new QI programs and studies are needed to develop strategies for facilitating workflow to enable quality-driven care.

Conclusion

The present study provides preliminary evidence for the potential for QI-focused education to help rheumatologists align their practices with evidence-based and consensus quality measures. Additional research will be necessary to identify and optimize educational interventions that yield significant and sustainable improvements in the quality of care for patients with RA.

References

Pradeep J, Watts R, Clunie G. Audit on the uptake of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(6):837–8.

Kahn KL, MacLean CH, Liu H, et al. Application of explicit process of care measurement to rheumatoid arthritis: moving from evidence to practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(6):884–91.

Schmajuk G, Schneeweiss S, Katz JN, et al. Treatment of older adult patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis: improved but not optimal. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):928–34.

Saag KG, Yazdany J, Alexander C, et al. Defining quality of care in rheumatology: the American College of Rheumatology white paper on quality measurement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):2–9.

Schmajuk G, Trivedi AN, Solomon DH, et al. Receipt of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Medicare managed care plans. JAMA. 2011;305(5):480–6.

Desai SP, Yazdany J. Quality measurement and improvement in rheumatology: rheumatoid arthritis as a case study. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3649–60.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Physician Quality Reporting System. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Index.html. Accessed Aug 4, 2015.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Payment Adjustment Information. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Payment-Adjustment-Information.html. Accessed Aug 4, 2015.

Shojania KG, Silver I, Levinson W. Continuing medical education and quality improvement: a match made in heaven? Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):305–8.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). About the National Quality Strategy (NQS). http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about.htm. Accessed Aug 4, 2015.

TE Kazi S, McNiff K, Barnes I. Early experience with the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Rheumatology Clinical Registry (RCR) [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:993. doi:10.1002/art.28760.

Desai SP, Liu CC, Tory H, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis quality measures and radiographic progression. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(1):9–13.

Davis D, Galbraith R. Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: american College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Educational Guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 Suppl):42s–8s.

Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P, Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867–74.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:Cd003030.

Mansouri M, Lockyer J. A meta-analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27(1):6–15.

Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, et al. Effectiveness of continuing medical education. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2007;149:1–69.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:Cd000259.

Desai SP, Solomon DH. A new paradigm of quality of care in rheumatoid arthritis: how our new therapeutics have changed the game. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):121.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship for this study was funded by an educational grant from Genentech (South San Francisco, CA, USA). Sponsorship for article development and processing charges was funded by PRIME Education, Inc. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. The authors presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Alliance for Continuing Education in the Health Professions in January 2015.

Disclosures

Tamar Sapir, Erica Rusie, Jeffrey Carter, Laurence Greene, and Kathleen Moreo represent PRIME Education, Inc., a healthcare education company that received an independent educational grant from Genentech to conduct the quality improvement project described in this article. Genentech had no role in the study design or execution, and the grant did not include support for writing this manuscript or paying publication charges. Barry Patel represents Indegene Total Therapeutic Management, a research company contracted by PRIME Education to perform the chart audits for this study. Jinoos Yazdany, Mark Robbins, and Eric Ruderman received honoraria from PRIME Education, Inc. for participation as faculty in the project’s continuing education activities. The authors did not receive payment for writing this article.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

The QI education program and outcomes study were approved by an independent institutional review board (Sterling IRB, Atlanta, GA; IRB ID #4534). This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sapir, T., Rusie, E., Greene, L. et al. Influence of Continuing Medical Education on Rheumatologists’ Performance on National Quality Measures for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther 2, 141–151 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-015-0018-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-015-0018-7