Abstract

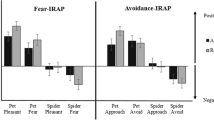

Recent research suggests that fear and avoidance responding based on derived transformation of functions may be considered functionally independent. The current study examined the impact of a fear-related verbal-rehearsal task on performance on two implicit relational assessment procedures (IRAPs), actual approach behavior towards a live spider (a BAT), and the relationship between the IRAPs and the BAT. The study was conducted over 3 separate days. Day 1 involved exposure to a series of questionnaires, the fear-related verbal-rehearsal task and homework. Day 2 involved a second exposure to the fear-related verbal-rehearsal task and exposure to the IRAPs and BAT. The final day involved a second exposure to the IRAPs and BAT. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions (i.e., control, accept, or reduce fear). Broadly similar findings were obtained for performance on the IRAPs as were reported by Leech et al. (2017). No significant differences between the conditions emerged on the self-report measures, IRAPs, or the BAT. However, correlations between performances on the IRAPs and the BAT were concentrated almost exclusively in the control and reduce-fear conditions rather than the accept-fear condition. The replication of results reported here provide further evidence of the functional independence of approach and avoidance responding. Furthermore, the differential pattern of correlations observed provide further evidence that the fear-related verbal-rehearsal task affected a behavior–behavior relation, which may be directly relevant to the concept of defusion in the ACT literature. In addition, the differential arbitrarily applicable relational responding effects (DAARRE) model offers an alternative explanation for the results reported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

By “exposure” we mean in the physical presence of/responding to the stimuli/tasks and not in a highly technical way or clinical/therapeutic sense.

Some of the phrases used in the avoidance-IRAP may be considered as referring to escape rather than avoidance per se. Here we wish to clarify that the statements are reflective of a participants desire to avoid the stimulus by means of escape or avoidant behavior. That is, the statements are reflective of experiential avoidance and the IRAP is assessing the relational networks that cohere with avoidance behaviors.

The other spider trial-type (spider-avoid) could also be seen as producing different responses from high- and low-fear participants but in this case they both produce a tendency towards picking “No.” That is, the low-fear participants may experience a “Yes–No” effect and thus tend towards picking “No” based on the incoherence between the label and target; the high-fear participants may experience a “No–No” effect and thus also tend towards picking “No” but simply because two “negative” reactions may cohere with “false” more readily than “Yes.”

Abbreviations

- IRAP:

-

Implicit relational assessment procedure

- BAT:

-

Behavioral approach task

- DAARRE:

-

Differential arbitrarily applicable relational responding effects model

- ACT:

-

Acceptance and commitment therapy

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21

- AAQ-II:

-

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire II

- FSQ:

-

Fear of Spiders Questionnaire

- ANOVA:

-

One-way analyses of variance

References

Augustson, E. M., & Dougher, M. J. (1997). The transfer of avoidance evoking functions through stimulus equivalence classes. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 28(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(97)00008-6.

Bernaerts, I., De Groot, F., & Kleen, M. (2012). De AAQ-II (Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II), een maat voor experiëntiële vermijding: normering bij jongeren. Gedragstherapie, 45, 389–400.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R., Carpenter, K., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007.

deBeurs, E., vanDyck, R., Marquenie, L., Lange, A., & Blonk, R. W. B. (2001). De DASS; een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress. Gedragstherapie, 34(1), 35–53.

Donati, M. R., Masuda, A., Schaefer, L. W., Cohen, L. L., Tone, E. B., & Parrott, D. J. (2019). Laboratory analogue investigation of defusion and reappraisal strategies in the context of symbolically generalized avoidance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 112(3), 225–241.

Dougher, M. J., Augustson, E., Markham, M. R., Greenway, D. E., & Wulfert, E. (1994). The transfer of respondent eliciting and extinction functions through stimulus equivalence classes. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 62(3), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1901/jeab.1994.62-331.

Hayes, S. C., & Brownstein, A. J. (1986). Mentalism, behavior-behavior relations, and a behavior-analytic view of the purposes of science. The Behavior Analyst, 9(2), 175–190.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(Pt 2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657.

Leech, A., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Madden, L. (2016). The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a measure of spider fear, avoidance, and approach. The Psychological Record, 66(3), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0176-1.

Leech, A., Barnes-Holmes, D., & McEnteggart, C. (2017). Spider fear and avoidance: a preliminary study of the impact of two verbal rehearsal tasks on a behavior–behavior relation and its implications for an experimental analysis of defusion. The Psychological Record, 67(3), 387–398.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research & Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U.

Luciano, C., Valdivia-Salas, S., Ruiz, F. J., Rodríguez-Valverde, M., Barnes-Holmes, D., Dougher, M. J., Cabello, F., Sanchez, V., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Gutierrez, G. (2013). Extinction of aversive conditioned fear: Does it alter avoidant responding? Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2, 120–134 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.05.001.

Luciano, C., Valdivia-Salas, S., Ruiz, F. J., Rodríguez-Valverde, M., Barnes-Holmes, D., Dougher, M. J., Lopez-Lopez, J. C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Gutierrez-Martinez, G. (2014). Effects of an acceptance/diffusion intervention on experimentally induced generalised avoidance: A laboratory demonstration. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 101, 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.68.

Muris, P., & Merckelbach, H. (1996). A comparison of two spider fear questionnaires. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 27(3), 241–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7916(96)00022-5.

Nicholson, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2012). The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a measure of spider fear. The Psychological Record, 62, 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0176-1.

Paez-Blarrina, M., Luciano, C., Gutiérrez-Martínez, O., Valdivia, S., Ortega, J., & Rodríguez-Valverde, M. (2008). The role of values with personal examples in altering the functions of pain: Comparison between acceptance-based and cognitive-control-based protocols. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 46(1), 84–97.

Szymanski, J., & O’Donohue, W. (1995). Fear of spiders questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 26(1), 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)00072-T.

Funding

This article was prepared with the support of an Odysseus Group 1 grant (2015–2020) awarded to the second author by the Flanders Science Foundation (FWO) and a doctoral research scholarship awarded to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Aileen Leech: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, formal analyses, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing; Dermot Barnes-Holmes: conceptualization, methodology, validation, supervision, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Code Availability

Not applicable

Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publication Consent

Participants signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Conflict of Interest

Aileen Leech declares that she has no conflict of interest. Dermot Barnes-Holmes declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 1064 kb)

Appendices

Appendix

Control Condition Script

Social Phobia Facts and Statistics

Social phobia is defined as the extreme fear of social situations where the individual is afraid of being judged by or embarrassed in front of other people. These are some of the most common phobias, affecting nearly 3% of the world’s population. More social phobia statistics:

-

Social phobias are often cultural, but they affect people of all races and social classes.

-

Interesting among social phobia facts is that more women than men are affected by them. People often confuse social phobias with shyness, which in general is more prevalent among women.

-

Phobia statistics reveal that only 23% of all people with phobias seek treatment for their anxiety.

-

Social phobias affect people of all ages, though they usually begin in adolescence. If phobia statistics and facts are to be believed, then nearly 40% of them begin before the age of 10, whereas 95% start before the age of 20.

-

The more common social phobias include fear of writing or eating before someone, meeting people of higher authority, using a telephone, or speaking before a large crowd etc.

-

Typical symptoms of social anxiety phobias are heart palpitations, dry mouth, hot/cold flashes, and trembling.

-

Another interesting fact is that nearly 45% of people with social phobias will develop agoraphobia and the fear of having an anxiety attack in public and embarrassing themselves. This is why many of these phobics try to avoid social situations.

-

Many people suffering from these phobias have experienced an impact in their personal and professional lives. Some refuse work promotions and others refuse to give presentations, attend meetings, or other activities that involve social interactions.

Specific Phobia Statistics and Facts

Specific phobias are characterized by an irrational or unwarranted fear of a specific situation, object, or animal. In some cases, these objects of dread can prove to be dangerous. Here are some specific phobia statistics:

-

Specific phobias begin during childhood and can persist throughout one’s life.

-

Nearly 15–20% of us experience specific phobias at least once in our life. In the United States, nearly 8.7% of people (aged 18 and older) have at least one extreme specific fear and nearly 25 million Americans report having fear of flying.

-

Specific phobias, namely zoophobias, can affect people of all ages, backgrounds, or socioeconomic statuses.

-

More research is needed to isolate the gene responsible for triggering such phobias. However, phobia statistics collected so far show that individuals with a parent or a close relative suffering from specific phobias are likelier to develop the same phobia.

-

The part of the brain called the amygdala is responsible for triggering specific phobias and needs to be further studied to help better understand these disorders.

-

The most common specific phobias include fear of animals, fear of the environment (e.g., fear of rain, earthquakes), fear of blood/injury, fear of certain situations (e.g., claustrophobia, fear of traveling on bridges), fear of death, fear of certain body sensations, and fear of incontinence.

For the next task can you write down what you think some of the most common phobias are?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leech, A., Barnes-Holmes, D. Fear and Avoidance: A Three-Day Investigation on the Impact of a Fear-Related Verbal-Rehearsal Task on a Behavior–Behavior Relation. Psychol Rec 72, 89–104 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-021-00470-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-021-00470-1