Abstract

Clearance of the spine is an essential component of the evaluation of the blunt trauma patient. There is a wide body of evidence that serves as the basis for current clinical management guidelines. Despite this evidence, controversies persist regarding best practices for certain patient populations with suspected spine injury. This article reviews the current recommended guidelines for effective spinal evaluation and clearance after blunt trauma. The article also reviews the evidence base for these guidelines, highlights key findings, and outlines a selection of recent studies that aim to determine best practices for those subjects where best practice has yet to be fully defined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the USA, the majority of spinal trauma come from motor vehicle accidents, followed by falls, and then sports-related injuries [1, 2]. Because spinal trauma may not be immediately obvious during the initial evaluation of a trauma patient, presuming a spinal injury and employing proper immobilization (“spinal precautions”) of the entire spine at the primary survey should be the rule after blunt trauma. This approach to blunt spinal trauma—to empirically immobilize the entire spine until a clearance protocol can be performed—is in contrast to penetrating trauma where a more selective approach based on injury patterns is often more appropriate.

Delaying proper immobilization until a neurological injury is identified defeats the purpose of spinal clearance and can lead to potentially preventable extension of a SCI. Particular attention, and a high-index of suspicion, should be paid to those cases when the mechanism of injury is unknown or sensorium is altered, such as for the patient who presents after being “found down.”

There are two main goals in spinal clearance after blunt trauma: avoid missed injuries and identify patients without significant injuries. The process of spinal clearance aims to accomplish these goals as efficiently as possible. A delay in diagnosis of spinal injury is associated with worse outcomes [3–5]. Quickly identifying patients with significant injuries leads to timely interventions and focused management. For those without significant injuries, the clearance process leads to early mobilization (e.g., cervical collars, spine precautions, etc.) which has a substantial positive effect on patient care.

Basic Exam Components and Importance of Protocols

As for all trauma patients, evaluation begins with the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) primary and secondary surveys. For those patients where spinal injury cannot be ruled out, immobilization of the spine should occur concurrently with the initiation of the primary survey. A rigid cervical collar and a backboard are a bare minimum, but careless patient handling will put any patient—regardless of immobilization devices—at risk for injury. Patient handling should reflect the presumption of a spinal injury.

Completion of the primary and secondary survey is the first step in the complete evaluation of the spine and an attentive examiner can sometimes identify patterns of injury that can be associated with blunt spinal injury: facial trauma, (cervical spine), face or neck abrasions from seat belts (cervical), lap belt contusion (thoracolumbar), and calcaneal fractures (thoracolumbar/lumbar). Established protocols that clearly delineate an established routine for how spinal clearance should be carried out are particularly important. Theologis et al. [2] have shown that lack of institutional protocol is commonplace, noting 57 % of level I trauma centers included in their study did not have a written protocol for cervical spine clearance. The authors of the study also highlighted how absent or unclear spinal clearance protocols can lead to inappropriate and unsafe patient care.

The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) provides readily accessible, evidence-based guidelines for both cervical and thoracolumbar spinal clearance [6, 7]. Employing evidence-based guidelines leads to protocols that effectively avoid missed injuries and also limit the unnecessary radiographic workup, and decrease the incidence of complications of prolonged immobilization [8]. In the pediatric trauma population, these protocols have the added benefit of limiting radiation exposure [9].

Cervical Spine Clearance

The aim in cervical spine clearance is to remove the cervical collar as quickly as possible from patients who do not benefit from them. This can be accomplished by clinical (i.e., by examination alone) means (“clinical clearance”) for some patients, but depending on the clinical circumstances, additional radiographic studies (“radiographic clearance”) may be necessary.

Clinical Clearance of the Cervical Spine

Patients who are alert and stable are potential candidates for clinical clearance. The Canadian C-spine Rule (CCR) [10] and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) [11] criteria have both been used to identify patients at low risk for cervical spine injury and therefore do not benefit from radiographic studies to effectively rule out unstable spine injury. Both the CCR and NEXUS studies were developed after the observation of significant practice pattern variability and indiscriminate use of radiography in these low-risk patients. Obtunded patients and patients whose mental status precludes evaluation require further workup and radiographic clearance.

National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS)

The NEXUS criteria for cervical clearance are based on a prospective study of ED patients who sustained blunt trauma. From this study, the NEXUS group recommended a set of criteria patients must meet. Patients who do not meet all five criterion required radiographic evaluation: no posterior midline cervical spine tenderness; no evidence of intoxication; a normal level of alertness; no focal neurologic deficit; no painful distracting injuries. The sensitivity of the NEXUS criteria as originally published was greater than 99.5 % [11].

Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR)

The CCR, also developed from a large prospective study, adds additional risk assessment including mechanism of injury and physical examination information that NEXUS lacks [10].

All of these patients require radiography: ≥65 years old; dangerous mechanism; paresthesias. If none of the following are met, these patients also require radiography: simple rear-end motor-vehicle collision; sitting position in the emergency department; ambulatory at any time after the accident; delayed onset of neck pain; no midline cervical tenderness.

NEXUS vs. CCR

In 2003, the authors of the original CCR study in 2001 conducted a direct comparison in that remains the only major study comparing the two protocols. The major finding was missed injuries in the NEXUS group [10]. Of 169 patients with cervical spine injuries, NEXUS protocols missed 16 injuries and CCR protocol missed 1. Overall, the CCR was found to be both more sensitive (99.1 vs. 90.7 %) and more specific (45.1 vs. 36.8 %).

Anderson et al. [12] performed a meta-analysis of the major studies comparing cervical spine clearance protocols and concluded that sensitivity and specificity were indeed better in the CCR protocols, but suggested that the functional evaluation (range of motion) had significant contribution to its diagnostic accuracy and could potentially be added to the NEXUS protocol to improve its accuracy in cervical spine clearance.

An additional systematic review published in 2012 evaluated 15 articles that studied either protocol published and had a similar conclusion as the Anderson study, supporting the superior diagnostic value of the CCR [13].

Morrison et al. [14] recently published a study retrospectively evaluating emergency department patients who had cervical spine imaging despite meeting NEXUS criteria for clinical clearance. Of 53 patients, 2 patients had significant cervical spine injuries on imaging.

Radiographic Clearance of the Cervical Spine

Radiographic clearance is necessary for any patient whose cervical spine cannot be cleared clinically. Utilization of radiographic clearance and deviation from NEXUS and CCR criteria (e.g., obtaining radiographic clearance even when medical clearance criteria are met) are reasonable in certain cases, especially the elderly: clinical judgment is tantamount, and if clinical suspicion is high, further workup should be pursued [14]. CT of the cervical spine is the mainstay of current radiographic clearance. MRI can be useful when an injury has already been diagnosed, but its role in clearance has yet to be defined in the literature. The utility of flexion and extension (“flexion-extension”) films to evaluate ligamentous injury is debatable, but is still employed by a significant number of trauma centers, especially for patients with negative CTs but persistent neck pain [2]. Plain films are not helpful for cervical spine clearance and should not be used for cervical spine evaluation after blunt trauma; their relevance is historical [15].Compared to CT, plain films are significantly less sensitive, less efficient, and less cost effective and should not be used for clearance of the spine after blunt trauma [2].

CT C-Spine

Over the past 15 years, CT has become the standard evaluation for all patients whose cervical spine cannot be cleared clinically. This practice shift has been supported by a number of clinical trials and systematic reviews. In the modern era, CT is the radiographic test of choice when a patient cannot be cleared clinically.

The superiority of CT over plain radiographs has been established since at least 2006 when Antevil et al. [16] conducted a retrospective review of blunt trauma patients during a period of transition from plain radiographs to CT at their institution. The authors found that CT was significantly more sensitive (100 vs. 70 %), but that patients had significant less time spent actually getting the radiographs completed. In 2009, Bailitz et al. [17] published results of a prospective analysis of 1,505 blunt trauma patients and found that plain radiographs had only 36 % sensitivity while maintaining the 100 % sensitivity in CTs, thus firmly establishing CTs superiority over plain radiographs for the cervical spine.

MRI C-Spine

MRI is useful for certain patients with abnormal CTs or diagnosed cervical spine injury and can aid in management and operative planning. It is the gold standard for injuries to the soft tissues, including ligaments, and the spinal cord.

The role for MRI cervical spine clearance, however, is not well established and there is significant debate about if it should be used and which patients stand to benefit the most.

A summary of the most recent studies on the subject of MRI is summarized in Table 1. In general, MRI is a reasonable consideration in screening for injuries for those patients with negative CT and who are obtunded or otherwise unevaluable, have midline cervical tenderness, have concomitant cerebral injury, or have a neurologic deficit. All of these clinical scenarios, however, are controversial, and more research needs to be done to determine MRI’s role. The strongest evidence in support of MRI as a screening modality is in the obtunded patient.

Common Clinical Issues in Cervical Spine Clearance

The Obtunded Patient With a Negative CT

MRI is the most commonly used modality to evaluate these patients [2]. And while some evidence supports the routine use of MRI for screening in these patients, there is still significant controversy. Several retrospective studies and systemic reviews have been conducted to determine the clinical utility of MRI in these cases (see Table 1). Several studies support the practice of clearing these patients on negative CT alone, based on the observation that most soft tissue injuries missed by CT are not clinically significant. On the other hand, two recent studies—including a systematic review by Russin et al. [18•]—support the continued use of MRI in the screening of these patients because of a small incidence of clinically significant injuries that would have been missed by CT alone. Given the potentially catastrophic nature of missed injuries, a small incidence is still important.

A large meta-analysis published by Panczynkowski in the Journal of Neurosurgery in 2011 [19] aimed to determine the utility of CT to rule out significant c-spine injuries in obtunded or injured patients. The meta-analysis contained 17 studies and a total of 14,327 patients. The authors found that CT had a negative predictive value of 100 % and concluded that CT was sufficient in these patients.

In 2013, Russin et al. [18•] published a study to evaluate the role of negative CT c-spine in radiographic clearance of unevaluable patients. In their systematic review, they included 13 studies (which included 1,322 patients) that included patients with clinically unevaluable cervical spine and negative CT c-spine who also underwent MRI. The authors concluded that CT was not sufficient for radiographic clearance due to the observation that 7 % of patients with negative CT c-spine had significant findings on MRI that changed management, including three patients who required surgical stabilization.

In 2014, Vanguri et al. [20] published results from their single center retrospective review of blunt trauma patients regarding the accuracy of CT in ruling out clinically significant c-spine injury. In the study, they limited the definition of “clinically significant” to those injuries that would require intervention. Although CT missed 32 of 52 ligamentous injuries, all 32 had clinically significant fractures that required intervention and were therefore considered appropriately detected by CT. The authors concluded from this that a negative CT was sufficient to remove cervical collar and no further workup for ligamentous injury (either flexion-extension or MRI) was needed. A similar study (retrospective database review of 1,004 patients), published by Chew et al. [4] came to a similar conclusion regarding CT’s utility in radiographic clearance. In this study, which focused on unevaluable patients and patients with persistent pain despite negative CT, the authors concluded that CT was sufficient to radiographically clear patients based on the observation that no clinically significant injuries were missed. Improved resolution has had some effect on the utility of CT in the setting of obtunded patients as well. After the observation of a 7 % missed injury rate in four-slice CT scanners, Kanji et al. [21•] set out to determine the effect of improved CT resolution (64-slice) on c-spine clearance in obtunded patients. The results of their meta-analysis results, although limited by small sample size, suggested that 64-slice scanners were equivalent to MRI in this setting (0 % missed injury rate).

Patients With Distracting Pain

The original NEXUS criteria study in 1998 defined distracting pain as long bone fracture, significant visceral injury, large laceration, a degloving or crush injury, large burn, or any other injury causing functional impairment [11]. This remains the most commonly used definition. Controversy exists, however, as to what truly constitutes a distracting injury, but these patients are at risk for prolonged immobilization and cervical collar placements that can result in pressure ulcers and skin infections as well as other squeal of immobilization like deep venous thromboses. Practice patterns vary with regard to how these patients are evaluated, but repeat clinical evaluations as well as MRI are common modalities. The concept of distracting pain was recently questioned by Kamenetsky et al. [22] in a prospective review of 160 patients with distracting injuries which were classified by clinical judgment and by objective pain scales in patients whose cervical spines were cleared if clinical exam (palpation) was negative. In this study, the authors found that clinical judgment was 98 % accurate in determining the significance of the distracting pain and that patients with asymptomatic cervical examination should be considered for clinical clearance even in the presence of distracting pain.

Persistent Pain, Negative CT

Delayed, repeat evaluation is an appropriate practice in select patients, but MRI is a common modality as well. But at least two recent studies support the practice of removing the cervical precautions with the negative CT result alone, although both studies are small and observational [23, 24]. Further studies need to be done to delineate the optimal management of spine clearance for these patients, but clinical judgment should determine the need for further workup in these patients.

Flexion-Extension Radiographs

Flexion-extension are the most commonly employed method for workup of patients with persistent pain with negative CT in trauma centers in the USA, despite lackluster evidence to support clinical utility [2]. In our own center, we have eliminated the use of flexion-extension films in low-risk patients and replaced it with CT for patients with higher risk.

The practice of using flexion-extension films was largely used in the patients with persistent neck pain, despite negative CT c-spine with the ostensible purpose of evaluating for ligamentous injury that may be missed on CT.

Although flexion-extension films are still a suggested option in the latest EAST guidelines, its role in current practice is waning. This is both because it is difficult to perform correctly and because of the theoretical risk of removing cervical immobilization in a patient with potential cervical injury. That said, the flexion-extension is still used at certain institutions, although it is not infrequently misused [2].

Tran et al. [25] recently published results from their retrospective analysis of data from their level I trauma center and found that positive flexion-extension films were either clinically insignificant (did not result in change in management) or non-specific when compared to the gold standard (MRI). From these results, the authors suggest that flex ex should be removed entirely from c-spine clearance protocols.

McCracken et al. [26] recently published a retrospective review of patients who underwent flexion-extension films and found that a large portion of the film are inadequate for clinical decision making (did not visualize C7/T1 and/or had less than 30° of flexion and extension), and that even in when they were adequately performed, the results were not clinically relevant to future management decisions. Sim et al. [27] came to a similar conclusion observing the same high incidence of inadequately performed flexion-extension films, as did Khan et al. [28] in their 2011 retrospective database study.

Thoracolumbar Spine Clearance

Thoracolumbar fractures are more common than cervical fractures after blunt trauma. The most common site of thoracolumbar injury is where the natural transition from kyphotic to lordotic curvature occurs, between T11 and L4 [29]. The approach to anyone with suspected thoracolumbar injury is immediate immobilization and careful patient handling that aims to minimize movement of the spinal column. At a bare minimum, patients should be placed on a backboard and placed on “log roll” precautions until an adequate clinical evaluation can be completed.

Like cervical spine fractures, there are patterns and types of fractures that are typical to this part of the spine and relate to the mechanism of injury. Spine instability correlates with the type of fracture which can sometimes be determined by plain radiographs, but instability is best evaluated by CT imaging. CT is superior when compared to plain radiographs in patients with suspected thoracolumbar spine injury. Compared to plain films of the thoracolumbar spine that miss up to 13 % of injuries, CT is significantly more sensitive, with one study reporting 99 % sensitivity [30]. This finding has been validated by several other studies.

In the presence of neurologic injury or suspected injury, MRI is the gold standard because of its unique ability to evaluate the spinal cord, intervertebral discs, and the ligaments. For the initial stages of evaluation after blunt injury, the MRI has no role, and CT is still first line. Selective use of MRI to evaluate high-risk injuries, such as burst fractures, even in the absence of neurologic deficits is reasonable but not well studied.

Clinical Clearance of the Thoracolumbar Spine

Unlike cervical spine clearance, algorithms that guide thoracolumbar spine clearance have not been rigorously tested or validated. Compared to the cervical spine, the thoracolumbar spine is difficult to examine. The thoracolumbar spine is relatively immobile, usually deeper to the overlying soft tissue, and initial evaluation by visual inspection and palpation requires adequate log roll and exposure which is an often an unreliable, if not completely ignored, part of the initial ATLS examination in the ED.

Clinical clearance of the thoracolumbar spine is not well described and the studies that support the utility of clinical clearance are based on a small number of retrospective studies. The essential components of the exam involve confirming the absence of gross neurologic deficits by history and confirming the ability to move all four extremities, followed by visual inspection of the spine and palpating for abnormalities while evaluating for midline tenderness.

EAST has also published guidelines for evaluation of the thoracolumbar spine, but lacks evidence-based support especially compared to cervical clearance guidelines. Because of the lack of rigorous data, there is no NEXUS or CCR counterpart that is applicable to evaluating the thoracolumbar spine, but it is generally accepted practice that for the patient who is alert, stable, undistracted, and without neurological injury or deficit on exam may be considered for clinically clearance. Patients who were ambulating after the injury are also considered lower risk for significant thoracolumbar injury. But because of lack of clear protocols and validated data, application of clinical clearance should be highly selective. The true incidence of thoracolumbar injuries is still unknown, but there is substantial evidence that current clinical clearance practices result in significant missed injuries. In 2011, Inaba et al. [31] published a prospective observational study evaluating clinical clearance of thoracolumbar spine after blunt trauma and found that of 666 patients with known thoracolumbar fracture, more than half (52 %) had a negative clinical exam. The TL-Spine Multicenter Study Group at Los Angeles County and University of Southern California has made significant contributions to help establish an evidence-based clinical decision tool. In 2014, Inaba et al. and the TL-Spine Multicenter Study Group presented research from a prospective multicenter trial of 3,068 blunt trauma patients. These results validated the finding that physical exam is of dubious clinical value for evaluation of the thoracolumbar spine, reporting a sensitivity and specificity of 78.4 and 72.9 %, respectively. This study added the finding that if age (≥60 years old) or high-risk mechanism (such as high-speed, falls from height, or pedestrians hit by automobiles), the sensitivity of clinical examination increased to 98.5 % [32].

Radiographic Clearance of the Thoracolumbar Spine

In 2012, Sixta et al. [7] published the most updated EAST guidelines for screening for thoracolumbar spine injuries after blunt trauma. In these guidelines, the authors point out that all but the most clear-headed, neurologically intact, and asymptomatic patients should be considered for clinical clearance. And even in these patients, a high-risk mechanism of injury alone should lead to serious consideration for radiographic clearance before spinal precautions are lifted. Cervical spine fracture is a risk factor for injury elsewhere in the spine and should result in thoracolumbar screening with CT. Significant concomitant non-spinal injuries should also prompt a radiographic evaluation of the thoracolumbar spine.

CT is the standard of care for immediate evaluation of the blunt trauma with suspected thoracolumbar spine injury. Modern CT scanners are highly sensitive and efficient.

Modern CT scanners that have the capability of computer-aided reconstructions have replaced plain films of the thoracolumbar spine. At least eight separate studies have described the inferiority of plain films as compared to CT in screening the thoracolumbar spine after blunt trauma [16, 30, 33–38]. There is no role for plain films of the thoracolumbar spine in any modern trauma center in the USA.

MRI’s role in thoracolumbar spine is only pertinent after a spine injury has been found, usually by CT. MRI is excellent for soft tissue, ligamentous, and spinal cord evaluation, but is inferior for bony structure injury when compared to CT. Because CT is more accurate and more efficient at detecting bony fractures and unstable spinal injuries, MRI has no role in screening or radiographic clearance of the thoracolumbar spine.

In 2013, Mitra et al. [39•] published an editorial delineating the current practices and evidence behind current practices in thoracolumbar spine evaluation after blunt trauma. In the editorial, the authors highlight the lack of a reliable clinical decision rule to help guide practice. Joaquim et al. [40] came to a similar conclusion as Mitra, in their recently published informal literature review summarizing recent studies on the subject of thoracolumbar.

In 2009, O’Connor et al. [41] proposed a set of criteria for thoracolumbar screening on a literature review of 16 observational studies. The authors suggested algorithm was largely similar to the NEXUS guidelines used in cervical clearance, with the added considerations of high-risk mechanism (e.g., high-speed MVC or fall from significant height) and any evidence of new cervical fracture because of the known association with simultaneous thoracolumbar fractures. The authors suggest that using this algorithm would lead to a high negative predictive value based on retrospective analysis of known and missed thoracolumbar injuries in the studies included in their analysis.

The Brigham and Women’s Experience

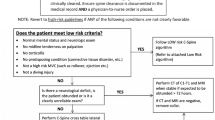

Our institution utilizes a protocol that builds on the NEXUS criteria and considers the mechanism of injury. For those patients who are deemed low risk and meet initial NEXUS criteria, the patient is clinically cleared and the collar removed. All other patients are evaluated by CT of the cervical spine. If CT is abnormal, we maintain spinal precautions and consult spine specialists.

If the CT is negative, we reassess the patient for clinical clearance. At this point, patients can be cleared if they have a reassuring exam, but persistent pain or focal neurologic deficits may lead to spine specialist consult, MRI, or both.

Specifically for the obtunded patient, we currently clear the cervical spine if the CT is negative for significant injury. Although there are some small, recent studies that suggest that CT misses a very small minority of injuries that MRI would detect, the majority of evidence supports clearance after negative CT. There are ongoing studies to address this controversial issue.

Conclusion

The aim of spinal clearance is to remove unnecessary immobilization as efficiently as possible.

For cervical spine clearance, adherence to the NEXUS criteria or CCR is necessary to guide which patients require further imaging. CT has become the standard of care to image the cervical spine. The role of MRI is for patients with an identified injury, worrisome exam, or for some centers, for clearance of obtunded patients.

For thoracolumbar spine clearance, except for the lowest risk blunt trauma patients (e.g., young, low-energy mechanism), clinical evaluation is unreliable. In addition, plain films are not sensitive or specific. Therefore, radiographic clearance with CT should be the rule rather than the exception. There is ongoing research to help establish better quality evidence to guide thoracolumbar evaluation.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Wang H, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal fractures: experience from medical university-affiliated hospitals in Chongqing, China, 2001–2010. 2014.

Theologis AA, Dionisio R, Mackersie R, McClellan RT, Pekmezci M. Cervical spine clearance protocols in level 1 trauma centers in the United States. Spine. 2014;39(5):356–61.

Bourassa-Moreau E, Mac-Thiong JM, Ehrmann Feldman D, Thompson C, Parent S. Complications in acute phase hospitalization of traumatic spinal cord injury: does surgical timing matter? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(3):849–54.

Chew BG, Swartz C, Quigley MR, Altman DT, Daffner RH, Wilberger JE. Cervical spine clearance in the traumatically injured patient: is multidetector CT scanning sufficient alone? Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(5):576–81.

Levi AD, Hurlbert RJ, Anderson P, Fehlings M, Rampersaud R, Massicotte EM, et al. Neurologic deterioration secondary to unrecognized spinal instability following trauma—a multicenter study. Spine. 2006;31(4):451–8.

Como JJ, Diaz JJ, Dunham CM, Chiu WC, Duane TM, Capella JM, et al. Practice management guidelines for identification of cervical spine injuries following trauma: update from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines Committee. J Trauma. 2009;67(3):651–9.

Sixta S, Moore FO, Ditillo MF, Fox AD, Garcia AJ, Holena D, et al. Screening for thoracolumbar spinal injuries in blunt trauma: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5 Suppl 4):S326–32.

Yang C, Hamielec C, Reid J. Pain in the neck: a review of cervical spine clearance processes in the critical trauma patient at a regional trauma center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:A2812.

Sun R, Skeete D, Wetjen K, Lilienthal M, Liao J, Madsen M, et al. A pediatric cervical spine clearance protocol to reduce radiation exposure in children. J Surg Res. 2013;183(1):341–6.

Stiell IG, Wells GA, Vandemheen KL, Clement CM, Lesiuk H, De Maio VJ, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule for radiography in alert and stable trauma patients. Jama J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(15):1841–8.

Hoffman JR, Wolfson AB, Todd K, Mower WR. Selective cervical spine radiography in blunt trauma: methodology of the National Emergency X-radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS). Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(4):461–9.

Anderson PA, Gugala Z, Lindsey RW, Schoenfeld AJ, Harris MB. Clearing the cervical spine in the blunt trauma patient. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(3):149–59.

Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Rebbeck T, Lin CW. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and NEXUS to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following blunt trauma: a systematic review. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Med Can. 2012;184(16):E867–76.

Morrison J, Jeanmonod R. Imaging in the NEXUS-negative patient: when we break the rule. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):67–70.

Griffen MM, Frykberg ER, Kerwin AJ, Schinco MA, Tepas JJ, Rowe K, et al. Radiographic clearance of blunt cervical spine injury: plain radiograph or computed tomography scan? J Trauma. 2003;55(2):222–6. discussion 6-7

Antevil JL, Sise MJ, Sack DI, Kidder B, Hopper A, Brown CV. Spiral computed tomography for the initial evaluation of spine trauma: a new standard of care? J Trauma. 2006;61(2):382–7.

Bailitz J, Starr F, Beecroft M, Bankoff J, Roberts R, Bokhari F, et al. CT should replace three-view radiographs as the initial screening test in patients at high, moderate, and low risk for blunt cervical spine injury: a prospective comparison. J Trauma. 2009;66(6):1605–9.

Russin JJ, Attenello FJ, Amar AP, Liu CY, Apuzzo ML, Hsieh PC. Computed tomography for clearance of cervical spine injury in the unevaluable patient. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(3-4):405–13. Aimed to determine if CT-alone was sufficient to clear the cervical spine of unevaluable patients after blunt trauma, this systematic review of 13 articles included 1322 patients who had both CT and MRI results available to review. The key finding in this study was that 52% (60 patients) of patients who had a negative CT had clinically significant MRI findings that changed management.

Panczykowski DM, Tomycz ND, Okonkwo DO. Comparative effectiveness of using computed tomography alone to exclude cervical spine injuries in obtunded or intubated patients: meta-analysis of 14,327 patients with blunt trauma. A review. J Neurosurg. 2011;115(3):541–9.

Vanguri P, Young AJ, Weber WF, Katzen J, Han JF, Wolfe LG, et al. Computed tomographic scan: it’s not just about the fracture. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(4):604–7.

Kanji HD, Neitzel A, Sekhon M, McCallum J, Griesdale DE. Sixty-four-slice computed tomographic scanner to clear traumatic cervical spine injury: systematic review of the literature. J Crit Care. 2014;29(2):314.e9–13. Another systematic review that included patients with both CT and MRI results, analyzed the effect of higher resolution (64-slice) CT scan on cervical spine clearance for obtunded patients and concluded that higher resolution CT scanner was at least as good as MRI.

Kamenetsky E, Esposito TJ, Schermer CR. Evaluation of distracting pain and clinical judgment in cervical spine clearance of trauma patients. World J Surg. 2013;37(1):127–35.

Resnick S, Inaba K, Karamanos E, Pham M, Byerly S, Talving P, et al. Clinical relevance of magnetic resonance imaging in cervical spine clearance: a prospective study. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(9):934–9.

Soult MC, Weireter LJ, Britt RC, Collins JN, Novosel TJ, Reed SF, et al. MRI as an adjunct to cervical spine clearance: a utility analysis. Am Surg. 2012;78(7):741–4.

Tran B, Saxe JM, Ekeh AP. Are flexion extension films necessary for cervical spine clearance in patients with neck pain after negative cervical CT scan? J Surg Res. 2013;184(1):411–3.

McCracken B, Klineberg E, Pickard B, Wisner DH. Flexion and extension radiographic evaluation for the clearance of potential cervical spine injures in trauma patients. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(7):1467–73.

Azoury SC, Dhanasopon AP, Hui X, Tuffaha SH, De La Cruz C, Liao C, et al. Endoscopic component separation for laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair: a single institutional comparison of outcomes and review of the technique. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg. 2014.

Nasim S, Khan S, Alvi R, Chaudhary M. Emerging indications for percutaneous cholecystostomy for the management of acute cholecystitis—a retrospective review. Int J Surg. 2011;9(6):456–9.

Looby S, Flanders A. Spine trauma. Radiol Clin N Am. 2011;49(1):129–63.

Hauser CJ, Visvikis G, Hinrichs C, Eber CD, Cho K, Lavery RF, et al. Prospective validation of computed tomographic screening of the thoracolumbar spine in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55(2):228–34. discussion 34–5.

Inaba K, DuBose JJ, Barmparas G, Barbarino R, Reddy S, Talving P, et al. Clinical examination is insufficient to rule out thoracolumbar spine injuries. J Trauma. 2011;70(1):174–9.

Inaba K, Nosanov L, Menaker J, Bosarge P, Turay D, Cacheco R, et al. Prospective, multicenter derivation of a clinical decision rule for thoracic and lumbar spine evaluation after blunt trauma. The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Annual Meeting; Philadelphia; 2014.

Sheridan R, Peralta R, Rhea J, Ptak T, Novelline R. Reformatted visceral protocol helical computed tomographic scanning allows conventional radiographs of the thoracic and lumbar spine to be eliminated in the evaluation of blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003;55(4):665–9.

Wintermark M, Mouhsine E, Theumann N, Mordasini P, van Melle G, Leyvraz PF, et al. Thoracolumbar spine fractures in patients who have sustained severe trauma: depiction with multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2003;227(3):681–9.

Roos JE, Hilfiker P, Platz A, Desbiolles L, Boehm T, Marincek B, et al. MDCT in emergency radiology: is a standardized chest or abdominal protocol sufficient for evaluation of thoracic and lumbar spine trauma? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(4):959–68.

Herzog C, Ahle H, Mack MG, Maier B, Schwarz W, Zangos S, et al. Traumatic injuries of the pelvis and thoracic and lumbar spine: does thin-slice multidetector-row CT increase diagnostic accuracy? Eur Radiol. 2004;14(10):1751–60.

Brandt MM, Wahl WL, Yeom K, Kazerooni E, Wang SC. Computed tomographic scanning reduces cost and time of complete spine evaluation. J Trauma. 2004;56(5):1022–6. discussion 6-8.

Berry GE, Adams S, Harris MB, Boles CA, McKernan MG, Collinson F, et al. Are plain radiographs of the spine necessary during evaluation after blunt trauma? Accuracy of screening torso computed tomography in thoracic/lumbar spine fracture diagnosis. J Trauma. 2005;59(6):1410–3. discussion 3.

Mitra B, Thani HA, Cameron PA. Clearance of the thoracolumbar spine—a clinical decision rule is needed. Injury. 2013;44(7):881–2. An editorial published in 2013, the authors outline the current evidence – and evidence gaps – that guide our current understanding and research into best practices for evaluating and clearing the thoracolumbar spine after blunt trauma.

Joaquim AF, Lawrence B, Daubs M, Brodke D, Tedeschi H, Vaccaro AR, et al. Measuring the impact of the thoracolumbar injury classification and severity score among 458 consecutively treated patients. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37(1):101–6.

O’Connor E, Walsham J. Review article: indications for thoracolumbar imaging in blunt trauma patients: a review of current literature. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21(2):94–101.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Allan B. Peetz and Ali Salim declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Blunt Spinal Trauma

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peetz, A.B., Salim, A. Clearance of the Spine. Curr Trauma Rep 1, 160–168 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-015-0019-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-015-0019-6