Abstract

The study of reputation figures prominently in management research, yet the increasing number of publications makes it difficult to keep track of this growing body of literature. This paper provides a systematic review of the literature based on a large-scale bibliometric analysis. We draw on bibliographic data of 5885 publications published until 2016, inclusively, and combine co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling with network visualization. Results show how research on corporate reputation is embedded in the broader field of scholarship on reputation in general. When zooming into the publication cluster on corporate reputation more closely, the concept’s origins in economics, organizational studies, and marketing as well as corresponding theoretical and methodological discussions are revealed. Beyond providing a structured overview of the field, the bibliometric analyses also reveal conceptual incoherencies that lead to ambiguities in research. Our assessment builds on the philosophy of science and is guided by the criteria of good concepts in social sciences. It shows that the concept of corporate reputation lacks internal coherence and could have more theoretical utility. We recommend focusing on corporate reputation as an attitudinal concept and thereby emphasizing the stakeholder who acts as an evaluator of the corporation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since the 1990s, corporate reputation has figured prominently in management research (Rindova et al. 2010). Researchers consider the reputation of a corporation to be its overall appeal (Fombrun 1996), its fame and esteem (Hall 1992), a signal of key characteristics (Fombrun and Shanley 1990), and attributes derived from past actions (Weigelt and Camerer 1988, p. 443). Reputation matters also to corporate practice (e.g., Alniacik et al. 2012; Deephouse and Carter 2005), because it is a valuable intangible asset (e.g., Deephouse 2000) that may contribute to competitive advantage (Hall 1992; for an overview of the competitive advantages that a good reputation can offer to different stakeholder groups, see Schwaiger and Raithel 2014) and to superior financial performance (Roberts and Dowling 2002). Fombrun et al. (2000) ascribe this dual interest—from both academics and practitioners—to the popularity of the annual Fortune ranking. Despite being a practitioner’s rating (Alniacik et al. 2012; Raithel et al. 2010), which was originally not intended for scholarly study (Deephouse 2000), Fortune’s “America’s Most Admired Companies” (AMAC) measurement of reputation is popular among management scholars too (van Riel and Fombrun 2007).

The importance of reputation in the management research is reflected in the growing number of publications dealing with this topic. Figure 1 shows the distribution of related publications over the last decades. We performed a data query in the Scopus® Database by entering the search term “reputation” in the fields of title, abstract, and keywords of academic publications in the subject area of Business, Management, and Accounting. The resulting growth curve of scholarly publications on reputation underscores the popularity of the concept in recent management research. As a consequence, it is increasingly difficult to obtain an overview of the literature, the more so as corporate reputation is applied in several subfields of management research, builds on different theoretical foundations, is not clear-cut from similar concepts, and is operationalized in empirical studies in various ways (e.g., Ali et al. 2015; Dowling 2016). Researchers acknowledge that “the concept of corporate reputation remains unclear” (Chun 2005, p. 92) and is “simple and complex” (Lange et al. 2011, p. 154) at the same time.

The vast and varied literature on corporate reputation, which was recently considered to be in a state of paradigm development (Chun 2005), calls for a systematic review. The previous qualitative reviews provide valuable insights into the research field (e.g., Lange et al. 2011; Rindova et al. 2005), but they are inherently limited, because they are subjective in the selection of relevant literature and have a limited scope due to the method of narration (e.g., Walker 2010). Systematic reviews can provide a reasonable alternative (Tranfield et al. 2003). The advantage of those reviews lies in a “replicable, scientific, and transparent process” (Tranfield et al. 2003, p. 209) that enables the researcher to provide “an audit trail, justifying his/her conclusions” (Tranfield et al. 2003, p. 218). A particular approach to systematic reviews is bibliometrics, i.e., the quantitative analysis of scholarly communication through publication (Verbeek et al. 2002). To the best of our knowledge, the present paper provides the first bibliometric review of corporate reputation in the management research, thus complementing qualitative reviews and updating them to the latest publications.

The aim of this review is to provide orientation in the extensive field of research on corporate reputation and to advance the scholarly understanding of the concept. For this purpose, we systematically structure the body of literature on corporate reputation to detect its main trajectories. In contrast to the previous reviews, we substantially extend the scope of the literature covered by the analysis. Our initial data set for the bibliometric analysis comprises 5885 articles on reputation. These data are reduced in a stepwise and systematic manner using the complementary bibliometric methods of co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling. At high levels of abstraction, we detect clusters of foundational and current research on corporate reputation and show how these strands of research are interconnected. To further elaborate the conceptual incoherencies revealed by the bibliometric analysis, we adopt a framework for the assessment of concepts from the philosophy of science and evaluate the concept of corporate reputation against these criteria. On this basis, we focus on the approach to conceptualize corporate reputation as an attitude-like concept, i.e., a concept resulting from the evaluations of its stakeholders.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: the next section presents the data and methods of our bibliometric review. In Sect. 3, we report and visualize the results of the bibliometric analysis. We first analyze how research on corporate reputation is embedded in the broader field of scholarship on reputation in general. Then, we present the more detailed analyses by means of co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling. Section 4 discusses the strengths and weaknesses of the concept, substantiated with results of the previous analyses, and offers a recommendation on conceptualizing corporate reputation. The paper concludes in Sect. 5 with a discussion of limitations and implications for future research.

2 Data and methods

2.1 Data

We collected our data from Scopus®, which, according to the publisher, is the largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed literature. Since we were primarily interested in the field of management research, we limited the query to the subject area Business, Management, and Accounting. Furthermore, we focused on publications in English language and included only published articles, articles in press, conference papers, reviews, books, and book chapters while excluding other items such as editorials, reports, or letters. With these specifications, we entered the search term “reputation” in the fields of title, abstract, and keywords of documents published until 2016, inclusively. This complies with the common practice to start a bibliometric analysis in a rather broad search setting and to reduce the complexity at later stages through increasing levels of aggregation. Our initial search resulted in 5885 hits for each of which we downloaded the full bibliographic record including all references to other documents. Subsequently, these data were thoroughly corrected, because they usually suffer from inconsistencies, such as contradictory citation behaviors of authors. For example, books are cited in different languages and editions, and references may be incorrect due to misspellings and other mistakes. The corrected data set included 256,189 references to 155,880 different sources.

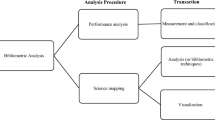

2.2 Methods

We applied two complementary bibliometric methods. Both methods are used to analyze co-occurrences in bibliographic data, yet at different levels and with different implications for the results. First, co-citation analysis combines all documents within the reference lists of academic publications with each other and aggregates for each pair of documents within the number of co-occurrences (Small 1973). Documents are thus co-cited when they appear in the same bibliography. Co-citation analysis is appropriate to uncover the traditions of a research area, because highly cited documents have a higher probability of co-citation with the other documents than less frequently cited works. Since the number of citations is to some extent a function of time, the ‘classics’, which have provided foundations for subsequent research, figure prominently in co-citation networks. Hence, co-citation analysis is a ‘dynamic’ procedure, because the number of (co-) citations is not fixed once the documents are published but may grow over time.

Second, bibliographic coupling counts the number of references that two (or more) documents share in their bibliographies (Kessler 1963). As opposed to co-citation analysis, which is conducted at the level of cited references, bibliographic coupling is an attribute of citing documents: two documents are coupled when they have at least one reference in common. Since bibliographic coupling is independent of the number of received citations, the method has a focus on the present and covers more recent works than co-citation analysis. The procedure is ‘static’, because the reference lists do not change once the documents are published. Hence, the degree to which documents are coupled is definite at the time of publication.

Due to these differences, co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling produce different yet complementary results. However, the structure of the aggregated data is the same: the raw data are reorganized in symmetric matrices with documents as column and row headers and number of co-occurrences as values. This structure of the data corresponds to the structure of networks: in the case of co-citation analysis, the column and row headers (i.e., network nodes) are cited documents and the values (i.e., network ties) are co-citations of each pair of documents. In contrast, the method of bibliographic coupling results in network data with citing documents as nodes and the number of couplings as ties. Accordingly, we used these matrices as inputs to a network analysis with UCINET Version 6.581. For the detection of subgroups within the networks, we applied the Girvan–Newman clustering procedure (Girvan and Newman 2002) as well as categorical core/periphery partition (Borgatti and Everett 1999). The network graphs were created with a spring embedding algorithm as provided by the NetDraw software version 2.153.

3 Results: mapping management research on corporate reputation

Our bibliometric analysis resulted in three separate yet interrelated networks. First, we present the ‘big picture’ of research on reputation in management and business studies and identify several clusters within this area (Sect. 3.1). The total network of bibliographic couplings shows how research on corporate reputation is embedded into, and interacts with, the broader field of related scholarship. Second, we zoom into the initial network and focus on the main cluster that is concerned with corporate reputation (Sect. 3.2). Since this is our overriding interest, we carry out the analysis in greater detail and present networks that result from both co-citation analysis and bibliographic coupling.

3.1 Reputation in business and management studies: bibliographic coupling

Figure 2 shows the total network of bibliographic couplings. As explained in the previous section, this method is particularly appropriate for mapping the research front, because it is independent of received citations (which grow only over lengthy periods of time). The nodes, representing citing documents, are connected to each other if they share eight or more references with at least three other publications. We applied this threshold to reduce the complexity of the network and to focus on academic discussions with a critical level of interrelatedness. Within this still large body of 786 publications, we extracted the eight clusters of research, which are highlighted by different node colors. Below, we briefly describe each cluster.

3.1.1 Cluster 1: corporate reputation

Cluster 1 is the main cluster in the network. It is not only located in the center of the network, but it is also the largest in terms of assigned publications, accounting for 71% of all nodes in the network. The documents almost exclusively focus on the analytical level of corporations as carriers of reputation. The cluster captures the scholarly discourse on measuring and modelling corporate reputation (e.g., Rindova et al. 2005; Ruiz et al. 2014; Sarstedt et al. 2013; Walsh and Beatty 2007), reviews the literature (e.g., Ferris et al. 2014; Lange et al. 2011; Walker 2010), and conceptualizes and defines the concept (e.g., Bitektine 2011; Chun 2005; Dowling 2016). This body of literature will be analyzed in greater detail in Sect. 3.2.

3.1.2 Cluster 2: auditing

Cluster 2 is rooted in accounting and revolves around the topic of auditing. The concept of reputation is mainly applied in the context of auditing firms and associated with quality (e.g., Bugeja 2011; Koh et al. 2013; Lim and Tan 2008; Singh 2013). Auditor reputation proves to be linked to a high quality of auditing (e.g., Lim et al. 2013; Swanquist and Whited 2015) and reporting (e.g., Cao et al. 2012; Cassell et al. 2016). A central issue is the auditors’ concern for reputation losses and litigation risks (e.g., Lim and Tan 2008; Park 2015). These concerns can influence the behavior of auditors (Duh et al. 2009; Larcker and Richardson 2004). Accordingly, auditors may deal strictly with clients, e.g., leaving a little space for earnings management (e.g., Hunt and Lulseged 2007), to protect their reputation. In addition, the influence of the reputation of auditors on their clients is examined. Auditor reputation can effect takeover premiums for a client’s shareholders (Bugeja 2011), cumulative abnormal returns (Cahan et al. 2009), costs of debt (Cano-Rodríguez et al. 2015), and stock prices (Numata and Takeda 2010).

3.1.3 Cluster 3: initial public offerings

Cluster 3 is rooted in finance and focuses on the initial public offerings (IPOs). Hence, most documents relate to the reputation of investment banks or other underwriters (e.g., Agrawal and Cooper 2010; He 2007; Dimovski et al. 2011; Jo et al. 2007), while a small number of documents in this cluster deals with the reputation of venture capital firms (e.g., Krishnan et al. 2011; Nahata 2008). Underwriter reputation is most commonly measured with Carter and Manaster’s (1990) tombstone ranking (Gygax and Ong 2011, p. 127) or Megginson and Weiss’ (1991) underwriter market share measure (e.g., Chen et al. 2013). Venture capital firm reputation is most commonly measured by the firm’s backed IPOs (e.g., Krishnan et al. 2011; Nahata 2008). A central issue in this cluster is how underwriter reputation (e.g., Deb 2013; Fernando et al. 2015; Su and Bangassa 2011) or venture capitalists’ reputation (e.g., Krishnan et al. 2011; Nahata 2008) is related to the success of IPOs.

3.1.4 Cluster 4: trust

Cluster 4 is concerned with the concept of trust. To a large extent, the documents assigned to this cluster address the interrelation of corporate reputation—more specifically, the reputation of sellers, vendors, or suppliers—and trust of consumers or users. How does seller/vendor/supplier reputation in online markets and exchange situations affect the formation of consumers’ trust (e.g., Ebert 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa 2004; Shareef et al. 2008; Teo and Liu 2007)? A large amount of research in this area focuses on cases in which the consumer has no experience with the seller and forms the initial trust (e.g., Chen and Barnes 2007; Fuller et al. 2007; Koufaris and Hampton-Sosa 2004).

Most commonly, reputation is measured in surveys by a broad set of items (e.g., Burda and Teuteberg 2014; Kim et al. 2008; Teo and Liu 2007) and analyzed by means of structural equation modelling (e.g., Burda and Teuteberg 2014; Kim and Ahn 2007; Pennington et al. 2003). Beyond trust building, several studies also address how reputation translates into a purchase intention of consumers (e.g., Dutta and Bhat 2016; Ponte et al. 2015; Shareef et al. 2008).

3.1.5 Cluster 5: service industries

Cluster 5 focuses on reputation management in service industries. Authors in this cluster, for example, investigate the relevance of word-of-mouth activities to the reputational management of theater and music festivals (Luonila et al. 2016), examine industry-specific dimensions of reputation in retailing services (Järvinen and Suomi 2011), and analyze the management of reputation risks in higher education and retailing services (Suomi and Järvinen 2013; Suomi et al. 2014). These studies are predominantly based on qualitative research designs, such as single- and multi-case analysis. The cluster does not encompass the further operationalizations of reputation, with the exception of Järvinen and Suomi’s (2011) adoption of the RepTrak for private sector firms in a mixed methods approach.

3.1.6 Cluster 6: tourism and hospitality

Cluster 6 concentrates on the significance of online consumer reviews in the tourism and hospitality industry. Online consumer reviews and ratings have become an important driver of purchase intentions, especially for experiential goods such as hotel stays (e.g., Liu and Park 2015; Viglia et al. 2016; Xie et al. 2014). Within this cluster, researchers discuss two types of reputation: hotel reputation and reviewer reputation. Hotel reputation is understood as being built through consumer online reviews and ratings (e.g., Schuckert et al. 2015, 2016a), while reviewer reputation is built through the generated reviews of a consumer (Schuckert et al. 2016b). A high number of generated reviews are associated with a high reputation of the reviewer (Liu et al. 2016), because it reflects his or her experience (Schuckert et al. 2016b) and thus serves as an indicator of the quality of the provided information (Liu and Park 2015). The consumer-generated online reviews, as electronic word-of-mouth, are essential to the reputation management of the respective hotel managers (e.g., Baka 2016). Accordingly, a central issue is the response management by hotels to monitor and influence their reputation (e.g., Liu et al. 2015). A good reputation management of online hotel review sites can, for example, result in a higher occupancy rate (Viglia et al. 2016).

3.1.7 Cluster 7: electronic commerce

Cluster 7 deals with the online market. Publications assigned to this cluster explore how reputation systems or mechanisms work in an online environment, most commonly on the electronic commerce platform ebay (e.g., Bolton et al. 2013; Hayne et al. 2015; MacInnes et al. 2005). Reputation systems provide information about sellers and buyers and reduce asymmetric information between both through feedback mechanisms (e.g., Li and Xiao 2014; Sun and Liu 2010; Zhang et al. 2012). The majority of publications in this cluster focus on how feedback or ratings in an online market create the reputation of sellers or buyers (e.g., Cabral and Hortacsu 2010; Li 2010; Zhang 2006). For example, some studies regress auction or transaction prices on feedbacks or ratings (Grund and Gürtler 2008; Jolivet et al. 2016; Sun and Liu 2010). Other authors apply reputation in experimental settings, building on trust games as suggested by game theory (e.g., Abraham et al. 2016; Lumeau et al. 2015) and analyzing the production of feedbacks as a public goods problem (Bolton et al. 2013; Bolton et al. 2004). This indicates that a considerable proportion of the allocated documents in this cluster consider how reputation systems affect trust (e.g., Bolton et al. 2004; Dellarocas 2003; Li and Xiao 2014). The proximity to Cluster 4 is also evident from the graphical representation of the bibliographic network (Fig. 2).

3.1.8 Cluster 8: entrepreneurial networks

Cluster 8 considers the embeddedness of entrepreneurial firms into relational networks. Most authors in this cluster analyze how an entrepreneur’s success is contingent on his or her professional network (e.g., Witt 2004). The focus is on how networks and their reputation can positively influence an entrepreneurial business, e.g., in terms of growth rates (e.g., Jack 2005; Lechner et al. 2006; Lechner and Dowling 2003). The reputation of the network can also spill over to the entrepreneur and enhance his or her personal reputation (e.g., Jack 2005; Witt 2004). Table 1 provides a brief overview of the eight clusters emerging from the bibliographic coupling of reputation research in management and business studies.

The ‘big picture’ drawn from the analysis of the initial bibliographic network reveals that reputation is investigated in several subfields of management and business studies. Hence, we can support the previous reviews, suggesting that the field is multifaceted (Highhouse et al. 2009). The predominant object as carrier of reputation is the corporation (especially Clusters 1–4, 6, and 8). The concept also matters to research on services (Cluster 5). In addition, there is a focus on the formation of reputation through consumer ratings (Cluster 7). Accordingly, research across clusters associates diverse attributes with reputation, e.g., quality (Cluster 2), performance or market share (Cluster 3), prominence and honesty (Cluster 4), or network capital (Cluster 8). The central Cluster 1 is thus embedded in a diverse field of research with subject-specific approaches to the concept of reputation. The distribution of the nodes between the clusters shows that there is a central corporate reputation theme with corporate reputation being also discussed in specific business contexts (except for Cluster 4). This can be associated with the phenomenon of academic silos. Researchers within a silo are isolated in their academic neighborhood naturally citing each other. Once established, the edges between the nodes of a cluster are strengthened by means of a larger number of edges leading to a compaction of the silo.

Although Clusters 2–8 refer to reputation, they do not have a narrow focus on corporate reputation. Therefore, the bibliographic network primarily reveals how the literature on corporate reputation is currently embedded into the broader field of research and how closely it relates to other clusters within this field.

3.2 Corporate reputation in business and management studies

We subsequently focus on the first cluster in the total network, because research in this cluster is more specifically concerned with corporate reputation. First, we explore the origins and foundations of this research by presenting the results of a co-citation analysis. And second, we map the research front with the network of bibliographic couplings.

3.2.1 Co-citation analysis

Figure 3 shows the co-citation network of management research on corporate reputation. As explained in Sect. 2.2, co-citation analysis is appropriate for exploring the structure of the field in terms of foundational works, because the focus of this method is on frequently (co-) cited works that have gained the status of ‘classics’ over a long period of time. The diagram depicts the core of the co-citation network, which we separated from the periphery by means of a categorical core/periphery partition (Borgatti and Everett 1999). The nodes stand for cited documents and the edges reflect co-citations. The size of the nodes is proportional to their degree (i.e., the number of connections to the other nodes in the network). For reasons of a better readability, we display only network ties that reflect more than 13 co-citations. This threshold reduces the number of documents to 101 and enables us to focus on the most central documents that constitute the foundations of the research field. Although the network core is still very dense and, therefore, does not subdivide into further clusters, distinct origins of research can be detected.

The network shows that research in the field of corporate reputation is substantially built on works of a specific researcher: Charles Fombrun. The co-citation network encompasses seven documents written by Fombrun and co-authors, among which are the two by far most often cited documents in the center of the network (Fombrun 1996; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). The article by Fombrun and Shanley (1990) has been referred to as a “tipping point” (Carroll 2013, p. 2) and being “foundational” (Walker 2010, p. 359) in research on corporate reputation. Following this, the book by Fombrun (1996) has been acknowledged as “the next major development in the scholarly business literature” (Carroll 2013, p. 2) on corporate reputation. It is famous for its definition of corporate reputation (Ruiz et al. 2014; Wartick 2002), which is described as groundbreaking (Lange et al. 2011), and reads as follows: “A corporate reputation is a perceptual representation of a company’s past actions and future prospects that describes the firm’s overall appeal to all of its key constituents when compared with other leading rivals” (Fombrun 1996, p. 72).

A closer inspection of the papers in the core of the co-citation network reveals that three dimensions emerge inductively from the data: a theoretical, a methodological, and a conceptual dimension. In the following, we briefly introduce these three dimensions and delineate how relevant discussions have paved the way for corporate reputation research.

3.2.1.1 Theoretical dimension

The resulting network shows that the roots of corporate reputation research are multi-theoretical. First, we can detect foundations from economic game and signaling theory (Spence 1973, 1974). Besides foundational works on signaling theory, the network also contains studies linking signaling theory with reputational aspects (e.g., Basdeo et al. 2006; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Rindova et al. 2005). From this theoretical perspective, corporate reputation serves as a signal to a firm’s attributes or products (Shapiro 1983). Weigelt and Camerer (1988) build on game theory and outline how reputation emerges from past actions of a party. These actions signalize the attributes of the corporation.

Second, corporate reputation research has origins in the resource-based view (RBV). On one hand, the co-citation network contains seminal papers that have been foundational to the RBV (Barney 1991; Dierickx and Cool 1989; Wernerfelt 1984). On the other hand, it includes studies that link the RBV with corporate reputation (e.g., Flanagan and O’Shaughnessy 2005; Hall 1992, 1993). For example, Deephouse (2000) describes (media) reputation as an intangible strategic resource that can lead to competitive advantage. Research building on the RBV hence considers reputation as a valuable intangible resource with which superior financial performance can be achieved (Roberts and Dowling 2002).

Third, the co-citation network reveals that research on corporate reputation has origins in institutional theory, represented by foundational works (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Meyer and Rowan 1977) as well as basic research on legitimacy as a core aspect of institutional theory (Suchman 1995). Furthermore, some studies in the network link institutional theory with reputation research (e.g., Rao 1994; Rhee and Haunschild 2006) and reveal that reputation is connected to social approval (Staw and Epstein 2000). Thereby, institutional theory fosters an understanding of how corporate reputation develops in social interactions and can be viewed as a “collective awareness and recognition that an organization has accumulated in its organizational field” (Rindova et al. 2005, p. 1034).

The fourth theoretical origin of reputation research is provided by the literature on social responsibility. The network comprises basic works on stakeholder theory (Freeman 1984; Mitchell et al. 1997) as well as corporate social responsibility (e.g., McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Sen and Bhattacharya 2001) and corporate social performance (e.g., Carroll 1979; Clarkson 1995; Wood 1991). The latter forms the conceptual basis for empirical studies that show how corporate social performance is related to performance indicators such as corporate reputation (Brammer and Pavelin 2006; Turban and Greening 1997) and financial performance (Griffin and Mahon 1997; Orlitzky et al. 2003; Waddock and Graves 1997).

3.2.1.2 Methodological dimension

Besides theoretically conceptualizing reputation, a central aspect of corporate reputation research is as to whether and how reputation can be modelled and measured. Thus, the second foundational dimension detected in the network relates to methodological issues. Corporate reputation research draws on general statistical methods in psychology and marketing research (Baron and Kenny 1986; Hair et al. 1999; Nunnally 1967) and also has methodological origins in the marketing literature on structural equation models: the network contains basic research on structural equation models (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Fornell and Larcker 1981) as well as studies that apply structural equation models to corporate reputation (e.g., Schwaiger 2004; Walsh et al. 2009; Walsh and Beatty 2007). Helm (2005) points out that researchers need to understand the epistemic nature of reputation to model it meaningfully, either formative or reflective.

Besides these general methodological issues, the network comprises groundwork on modelling corporate reputation measures: reputation QuotientSM (Fombrun et al. 2000; Gardberg and Fombrun 2002), the Schwaiger model (Schwaiger 2004), and customer-based reputation (Walsh and Beatty 2007). In addition to these modelling approaches, foundational works predominantly rely on operationalizations of reputation using the Fortune index (e.g., Black et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2000; Srivastava et al. 1997). The main problem is that the Fortune index primarily reflects reputation as a function of company performance (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Fryxell and Wang 1994; McGuire et al. 1990). Accordingly, foundational research deals with the approaches to the determination of a financial halo on corporate reputation (Brown and Perry 1994; Roberts and Dowling 2002).

3.2.1.3 Conceptual dimension

The third foundational dimension of corporate reputation research is characterized by concepts closely linked to corporate reputation. The co-citation network comprises several works on the triad of identity, image, and reputation, which illustrates that these concepts are related to but still different from each other (Brown et al. 2006; Gioia et al. 2000; Gray and Balmer 1998; Whetten and Mackey 2002). This subject area shows that corporate reputation research is to a large extent influenced by marketing literature, which describes the three concepts as distinct mental associations of a corporation (Brown and Dacin 1997; Brown et al. 2006; Walsh et al. 2009). In particular, the network includes basic works on organizational identity (e.g., Ashfort and Mael 1989; Dutton and Dukerich 1991), which has been described as comprising the central character and distinctiveness of the organization and as being relatively stable over time (Albert and Whetten 1985). Organizational identity hence represents what organizational members believe the organization to be (Brown et al. 2006).

The network also comprises foundational works on corporate image (e.g., Dutton et al. 1994; Gatewood et al. 1993) and links it to reputation (e.g., Gotsi and Wilson 2001; Nguyen and Leblanc 2001). The image of a corporation is focused on its external appearance, with image being an immediate impression (Gray and Balmer 1998). Reputation, in contrast, develops over time (Gotsi and Wilson 2001).

With regard to reputation, both identity and image emphasize that one corporation is considered. In contrast, in the context of status and reputation, interorganizational comparisons are fostered (Deephouse and Carter 2005). The foundations of corporate reputation research address reputational status (Fombrun and Shanley 1990), organizational status in exchange partner selection (Jensen and Roy 2008), and the relation of a producer’s status and his product quality (e.g., Benjamin and Podolny 1999). In contrast to reputation, status sorts corporations into high- and low-status groups (Podolny 1993).

The co-citation network systematically reveals the multidimensional origins of corporate reputation research. While these origins can be traced back to economics (i.e., signaling and game theory) and organizational science (i.e., RBV, institutional theory, and stakeholder theory) in the theoretical dimension, they can be traced back to marketing in the methodological dimension. To complete the bibliometric analysis, we now move from the past traditions of research (as revealed by co-citation analysis) to the current trends (as detected by means of bibliographic coupling).

3.2.2 Bibliographic coupling

Figure 4 shows the network of bibliographic couplings in the first cluster of the full network (Fig. 2). This analysis directs the attention from foundational works to more recent publications at the research front. Again, we separated the core of the network (Borgatti and Everett 1999) and further reduced it to documents with more than 13 couplings, which resulted in a network of 125 documents. Since bibliographic coupling focuses on citing documents, the network represents more recent research on corporate reputation. We outline these trends primarily along the dimensions derived in the previous section (i.e., theoretical, methodological, and conceptual).

3.2.2.1 Theoretical dimension

There are two prominent theoretical perspectives of current research on corporate reputation: the RBV (e.g., De Castro et al. 2006; Deephouse 2000; Rindova et al. 2010; Rindova and Fombrun 1999; Sur and Sirsly 2013; Toms 2002) and signaling theory (e.g., Basdeo et al. 2006; Delgado-García et al. 2010; Philippe and Durand 2011; Ponzi et al. 2011; Walsh et al. 2009). To date, research on corporate reputation still lacks an indigenous theory of reputation (Ferris et al. 2014).

All documents of the bibliographic coupling network deal with the definition of corporate reputation to some extent. However, the current research shows that there is no agreement on one definition (e.g., De Castro et al. 2006; Dowling 2016; Lange et al. 2011; Walker and Dyck 2014). Within the theoretical dimension of the foundations of corporate reputation research (Sect. 3.2.1.1), we found that there is a multi-theoretical basis, which eventually causes the multitude of definitions in more recent research (Lange et al. 2011). The results of the bibliometric analysis show that Fombrun’s (1996) definition is the most popular (e.g., Moura-Leite and Padgett 2014; Reuber and Fischer 2011; Roberts and Dowling 2002). Most of the works in the network add further aspects to this definition: Fombrun and Shanley’s (1990) emphasis on the signaling effect of reputation (e.g., Devers et al. 2009) or Hall’s (1992) resource-oriented perspective on reputation as an intangible asset that represents fame and esteem (e.g., Deephouse 2000; Deephouse and Carter 2005).

The bibliographic network of the current research also comprises publications with extant reviews on the variety of definitions of reputation (e.g., Bitektine 2011; Chun 2005; Dowling 2016; Srivoravilai et al. 2011). Based on their reviews, some authors develop their own concept of reputation. Lange et al. (2011) describe three conceptualizations: being known, being known for something, and generalized favorability. Rindova et al. (2005) describe the two dimensions of reputation: perceived quality and prominence. Walker (2010) adds the two attributes stability in time and a positive to negative spectrum to Fombrun’s (1996) central attributes of reputation: perception, aggregate of all stakeholders, and comparability.

The multitude of definitions of corporate reputation is also apparent with regard to stakeholders. The definition of Fombrun (1996) emphasizes that reputation is the sum of all stakeholder perceptions (Walker and Dyck 2014). In contrast, there are definitions, stating that reputation differs depending on the stakeholder group (e.g., Mishina et al. 2012; Ruiz et al. 2014). In this context, the recent studies emphasize that different groups of stakeholders evaluate different reputational aspects (Ertug et al. 2016) and that different stakeholders form different judgements on the same attributes based on their fundamental beliefs (West et al. 2016).

Scholarly research also discusses how corporate reputation may emerge (e.g., Fischer and Reuber 2007, Petkova et al. 2008, Rindova et al. 2007) antecedents and consequences of reputation (see Sect. 3.2.2.2 for more details), which also finds ground in the commonly used resource-based perspective. While the current research does not provide a standard definition of corporate reputation, reference to intangible assets is common (e.g., Chun 2005; Deephouse 2000; Eberl and Schwaiger 2005; Pfarrer et al. 2010; Ponzi et al. 2011; Rindova et al. 2005, 2010; Roberts and Dowling 2002). Considering reputation as an intangible asset puts emphasis on the value and performance effect of reputation for the corporation (Roberts and Dowling 2002). Consequently, perceiving reputation as an intangible asset is inevitably linked to the RBV (Rindova et al. 2010). Although this interpretation is widely spread and the performance impact is thoroughly studied (Rindova et al. 2005), little is known about the attributes that make reputation an intangible asset (Rindova et al. 2010). The characterization of reputation as such an asset thus refers to the consequences arising from reputation, but not to the definitional essentials of reputation. The lack of clarity about what reputation is per se also leads to problems in operationalizing and measuring reputation (Ponzi et al. 2011).

3.2.2.2 Methodological dimension

Closely related to the definition of reputation is its empirical measurement (Walker 2010); both should correspond to each another (Kraatz and Love 2006). However, due to the ambiguous nature of the definition of corporate reputation, there is also pluralism and uncertainty about its measurement (Chun 2005; Clardy 2012; Dowling 2016; Eberl and Schwaiger 2005). Hence, the question of how to reasonably measure reputation is still of high interest in the recent research. This applies all the more as the current discourse on corporate reputation is dominated by empirical studies (Table 2).

The dominant method—used by more than half of the empirical documents—is regression analysis followed by structural equation modelling (e.g., Ponzi et al. 2011; Ruiz et al. 2014; Sarstedt et al. 2013; Walsh et al. 2009; Table 2). Researchers employ various operationalizations to measure corporate reputation: the Fortune ranking is most frequently used (e.g., Basdeo et al. 2006; Chandler et al. 2013; Love and Kraatz 2009; Musteen et al. 2010; Pfarrer et al. 2010), followed by the Reputation QuotientSM (e.g., Baldarelli and Gigli 2014), the RepTrak® Pulse (Ponzi et al. 2011), and the Schwaiger model (Raithel et al. 2010; Eberl and Schwaiger 2005) (Table 2). Reputation is also measured by means of alternative approaches, such as the coding of news articles (Deephouse 2000; Petkova 2014; Van den Bogaerd and Aerts 2015), customer satisfaction ratings (Jarmon 2009), or a corporate credibility index (Zhang and Rezaee 2009).

Although the Fortune ranking is popular in the current research, it is also broadly criticized (for an overview see e.g., Deephouse 2000). Given the popularity of this ranking, the subject of a financial halo–detected in the co-citation analysis (Sect. 3.2.1.2)—is also relevant to more recent research on corporate reputation. In this respect, Roberts and Dowling (2002) differentiate between financial reputation and residual reputation that includes all non-financial reputation. Consequently, most up-to-date research that relies on the Fortune ranking controls for the past financial performance influence (e.g., Basdeo et al. 2006; Musteen et al. 2010; Soana and Schwizer 2013). By contrast, Eberl and Schwaiger (2005) make the case for applying a measure of reputation that is free from a financial halo. They construct one part of corporate reputation as influenced by the past performance and another part as idiosyncratic.

Another critical aspect of the dominant use of the Fortune ranking can be found in a comprehensive study by Sarstedt et al. (2013). The authors analyze the top three of the measurement approaches mentioned above (i.e., Fortune AMAC, Reputation QuotientSM, and Schwaiger model) and two additional measurement approaches. They compare these measures in terms of convergent validity, which is part of construct validity, and criterion validity. Since construct validity assesses whether the analysis studies the “correct operational measures for the concept” (Yin 2014, p. 46), this analysis seems particularly interesting in light of the conceptualization and operationalization of the corporate reputation concept. When comparing the convergent validity of the models, the Schwaiger model emerges as the best, the Reputation QuotientSM achieves a similar result, but the Fortune AMAC falls behind (Sarstedt et al. 2013). The Schwaiger model and the Reputation QuotientSM also perform better than the Fortune AMAC in terms of criterion validity (Sarstedt et al. 2013, p. 336). Furthermore, in their study on the RepTrak System, Fombrun et al. (2015) reveal the validity of their measure across different stakeholder groups. For further insights on the pros and cons of reputation measures, see Dowling and Gardberg (2012).

Regarding the wide dissemination of the Fortune ranking, it should be noted that, despite all criticism, its popularity is based on the lack of alternatives. For a long time, no other databases for reputation research have been publicly (free of charge) available. With regard to the variables employed in the analyses, corporate reputation is commonly related to performance indicators. For example, the influence of analyst, CEO, and corporate reputation on cumulative abnormal returns of a corporation’s stock is analyzed both separately and jointly (Boivie et al. 2016), or the influence of corporate reputation on net income after tax and depreciation is examined (Eberl and Schwaiger 2005). Deephouse (2000) analyzes the influence of media reputation on return on asset, and Raithel et al. (2010) examine the influence of both cognitive and affective reputation components on the market to book value as a proxy for firm value. Further influences of reputation that are analyzed are, for example, related to customer behavior such as loyalty (Badri and Mohaidat 2014; De Leaniz and Rodríguez 2016; Echchakoui 2016), word-of-mouth (Ruiz et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2009), and customer support (Srivoravilai et al. 2011). The influences of customer satisfaction and corporate social responsibility (CSR) on reputation are frequently analyzed (see below), as are country factors such as the country-of-origin (Reuber and Fischer 2011) or institutional development and national culture (Deephouse et al. 2016).

The analysis of the bibliographic coupling network reveals that customers are one group of stakeholders on which the current research focuses (e.g., Jarmon 2009; Rhee and Haunschild 2006; Walsh and Beatty 2007). Dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of customer-based reputation are theorized and accordingly operationalized in different ways. For instance, research finds reliability as an antecedent (e.g., Ruiz et al. 2014) and dimension (Walsh and Beatty 2007) of customer-based reputation and customer loyalty as a consequence (e.g., De Leaniz and Rodríguez 2016; Ruiz et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2009). Customer satisfaction is theorized as an antecedent to reputation (e.g., Ruiz et al. 2014; Walsh et al. 2009), as an outcome variable (Walsh and Beatty 2007), as mediated by reputation (Ganesan and Sridhar 2016), or as a mediator—alongside reputation—between CSR and performance (Galbreath and Shum 2012; Saeidi et al. 2015). Corporate reputation is also theorized as a mediator for the relation of CSR or social performance to financial performance (e.g., Neville et al. 2005; Saeidi et al. 2015). In contrast, the extensive research on CSR or social performance as drivers of corporate reputation is consistent (e.g., Brammer and Pavelin 2006; Galbreath 2010; Melo and Garrido-Morgado 2012; Walker 2010).

The multifaceted discussion about antecedents and consequences goes beyond customer-based reputation and the relationship of CSR and corporate reputation. In a meta-analysis, Ali et al. (2015) find that relationships involving antecedents and consequences of corporate reputation are moderated by country, by the stakeholder group that is investigated, and by the reputation measure that is employed.

The analysis of the moderating variables is diverse. One moderating variable is a company’s past reputation. Love and Kraatz (2009) show that higher prior reputation reduces the loss of reputation in the course of downsizings. Philippe and Durand (2011) find that corporations with lower prior reputation receive higher rewards for certain norm-conforming behaviors. Another study analyzes the impact of product recalls on corporate reputation, which is moderated by the intensity of competition and the degree of specialization of the corporation (Rhee and Haunschild 2006).

To summarize, the theoretical uncertainty about the concept of corporate reputation, as described in the previous section, is also reflected in the efforts of current research to develop and empirically test measurement models (e.g., de Castro et al. 2006; Ponzi et al. 2011; Rindova et al. 2005; Walsh and Beatty 2007).

3.2.2.3 Conceptual dimension

The conceptual dimension outlined above—focusing on the concepts closely linked to corporate reputation—is no longer a central issue in the current discourse. Among the few exceptions are Chun’s (2005) review, making an explicit distinction between reputation, image, and identity, as well as Balmer’s study (2009), distinguishing reputation from image and identity in light of corporate marketing. In addition, reputation serves to explain other concepts such as organizational stigma (Devers et al. 2009).

It becomes apparent that the current research is characterized by a close interaction of the theoretical and the methodological dimension. These dimensions show disagreement on what the definitional aspects of the concept are as well as on what its antecedents and consequences are. The variety of definitional approaches to reputation translates into a pluralism also in the methodological dimension. In face of these conceptual ambiguities, the question arises as to what constitutes a good concept and how the development of such a concept can be fostered.

4 Discussion: assessment of the corporate reputation concept

The proof of the pudding is in the eating! If this statement is the cornerstone for the assessment of a concept (Bjørnskov and Sønderskov 2013), corporate reputation certainly is a successful concept. Our bibliometric analyses underscore this fact. The initial growth curve (Fig. 1) shows the increasing popularity of reputation in the management and business literature. However, a more detailed picture of the theoretical and methodical status quo of the concept (Sects. 3.2.2.1, 3.2.2.2) underlines that members of the scholarly community hold heterogeneous perceptions about how corporate reputation should be defined and operationalized. In the other words, reputation means different things for different researchers and proves to be a ‘moving target’. Not surprisingly, the concept is repeatedly criticized for lack of a uniform definition and a corresponding operationalization (e.g., Dowling 2016; Eberl and Schwaiger 2005). To date, it remains unclear what corporate reputation really is. The central dimensions—definition and measurement—of a popular concept are called into question repeatedly. Therefore, it is necessary to consider whether reputation is not only a successful but also a ‘good’ concept.

Gerring (1999) derives an evaluation system from the philosophy of science that he explicitly suggests for the evaluation of concepts in social sciences. The previous studies have already applied this framework to such concepts (e.g., Bozeman and Su 2015, Bjørnskov and Sønderskov 2013; Hilgers 2011). In the latest publication, Gerring and Christenson (2017) present a revised version of the framework. In the present study, we adopt this latest version, because it makes an explicit distinction between concept formation and empirically oriented operationalization.

Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) evaluation system consists of five criteria for assessing a concept: (1) resonance; (2) internal coherence; (3) external differentiation; (4) consistency; (5) theoretical utility (for an overview, see Gerring and Christenson 2017, p. 31–35). For most concepts, a trade-off between individual criteria is unavoidable (Gerring 1999). “Concept formation is a fraught exercise—a set of choices which may have no single ‘best’ solution, but rather a range of more-or-less acceptable alternatives” (Gerring 1999, p. 367). Essentially, concepts are linguistic instruments whose terms need to be defined (Gerring and Christenson 2017). Only then is a concept applicable to an empirical context by indicators that enable operationalization (Gerring and Christenson 2017). Suddaby (2010) argues similarly and emphasizes the necessity of clarity of concepts in the management and organizational theories: before being concerned with issues of validity, which are “empirical questions of operationalization and measurement” (Suddaby 2010, p. 346), a clear concept is required. The emphasis on the distinction between definition of concept and operationalization appears reasonable against the backdrop of the reputation concept. For these reasons, and based on the results of the bibliometric analyses, we discuss the concept of corporate reputation in two steps: first, we apply Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) criteria on the status quo of corporate reputation. Second, we discuss attempts by scholars to clarify the distinction between definition and operationalization and offer conceptual grounds following Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) advice to give priority to the theoretical concept.

4.1 Criteria for a good concept

4.1.1 Resonance

The first criterion, resonance, is concerned with the familiarity of a concept (Gerring and Christenson 2017). This criterion differentiates between two aspects of a concept, the text of the definition and the label of the concept. Regarding the first aspect, the corporate reputation concept appears to be comprehensible (Table 3) as researchers use common language to define it. This is also true for the second aspect, since the label corporate reputation is a familiar and common term. Accordingly, it can be concluded that corporate reputation is “intuitive and simple in its common usage” (Lange et al. 2011, p. 153) and causes a “cognitive click” (Gerring 1999, p. 370). Thus, resonance provides the basis for a concept to become popular. In the context of considerable scholarly work, the popularity of corporate reputation seems to be given.

4.1.2 Internal coherence

The second criterion, internal coherence, is concerned with the conformability of attributes ascribed to a concept in the scholarly discourse (Gerring and Christenson 2017). Accordingly, the coherence of attributes of different definitions has to be considered. The criterion also comprises the depth of a concept (Gerring and Christenson 2017), which refers to the extent of attributes comprised by a concept (Gerring 1999). Such attributes are, for example, emotions (Hall 1992) and feelings (Ferguson et al. 2000), which refer to an affective part of reputation, and knowledge of (Hall 1992) and thinking (Ferguson et al. 2000) done by stakeholders, which refer to a cognitive part of reputation (Table 3). In this regard, the concept of corporate reputation appears to have a certain depth.

Incoherencies between different conceptualizations of corporate reputation in the research are outlined in Sects. 3.2.1.1 and 3.2.2.1. The results of the bibliometric analyses show that there is incoherency concerning the scope of corporate characteristics, the scope of stakeholders whose perceptions create reputation, and between what reputation is and what its antecedents and consequences are. Fombrun’s (1996) definition (Table 3)—widely used in the current research on corporate reputation—refers to general actions of a corporation (Table 3). This general formulation implies that every action of a corporation contributes to its reputation—a fact that has already been criticized by Deephouse and Carter (2005). Empirical work shows that, in the end, not all actions have implications for reputation. For example, Karpoff et al. (2005) show that not all actions (in their case environmental violation) influence a corporation’s reputation, but that it depends on whether the stakeholder groups are affected by the action. Reuber and Fischer (2011) analyze discreditable actions of the reputation effects of which depend on perceived control, certainty, and threat or deviance. In addition, external stakeholder motivation and media coverage moderate the probability of a loss of reputation.

A further aspect concerning the internal coherence of corporate reputation concerns coherency within theoretical streams. Rindova and Martins (2012) demonstrate a certain coherence for the definitions of reputation within beliefs of reputation as signals, collective perceptions, or positions in rankings, but less across these streams. In addition, Dowling (2016) provides a comprehensive analysis of definitions of corporate reputation. It shows the incoherent conceptualizations that either take reputation as a belief or an evaluation, as a signal about certain aspects, or as the status of an organization (Dowling 2016). These groupings show that there is considerable coherence within certain theoretical streams but little coherence across them.

Table 3 provides an overview of definitions of corporate reputation with an emphasis on evaluations by stakeholders. The definitions focus on the emotions (Hall 1992), feelings (Ferguson 2002), judgments (Boivie et al. 2016), and admiration (Dowling 2016) of the evaluator. The definition by Fombrun (1996) also comprises the company’s past actions, which are criteria for the evaluation by stakeholders. This may be a reason for the diverse operationalizations of corporate reputation based on this definition (Sect. 4.1.5). The evaluator’s perspective will be discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.2.

The internal incoherency of the corporate reputation concept appears to be a critical factor in the discussion of whether it is a good concept. A concept with high internal coherence bundles characteristics that differentiate it from others (Gerring and Christenson 2017). Accordingly, the complementary counterpart of this criterion is external differentiation.

4.1.3 External differentiation

The third criterion, external differentiation, addresses the distinctiveness from the other closely related concepts and is thus concerned with the boundaries of a concept (Gerring and Christenson 2017). This study showed that the concept of corporate reputation is integrated into the field of research with concepts such as image, identity, and status, and is differentiated from these neighboring concepts (Sect. 3.2.1.3). The boundaries of the concept remain vague as corporate reputation is characterized in different ways (Sect. 4.1.2) and is thus not differentiated per se. This conceptual weakness is directly linked to issues of operationalization: a concept that lacks a clear differentiation will potentially have multiple operationalizations (Bjørnskov and Sønderskov 2013; Gerring 1999). As shown in Sect. 3.2.2.2, this applies to corporate reputation. This diversity reflects uncertainty about what corporate reputation is all about. Another challenge is that an imprecise definition of reputation can lead to confusion as to what its antecedents and consequences are. Ponzi et al. (2011, p. 16) claim “that the definition of the construct has been obscured with measurement of its drivers, and antecedents have been regularly used to measure the construct itself.”

4.1.4 Consistency

The fourth criterion, consistency, refers to the uniform usage of a concept within one study (Gerring and Christenson 2017). Concerning the concept of corporate reputation, this, again, seems to be problematic especially for the relation of defining and measuring the concept. The operationalization of the corporate reputation concept into empirically measurable indicators implies a lack of consistency. An example for the mismatch between defining and measuring corporate reputation is the combination of Fombrun’s (1996) definition and the operationalization by means of the Fortune ranking (see, e.g., Moura-Leite and Padgett 2014; Roberts and Dowling 2002). On one hand, Fombrun’s definition emphasizes that reputation is the sum of all stakeholder evaluations. On the other hand, the Fortune index is generated by surveying a certain group of stakeholders (managers and analysts) (e.g., Deephouse 2000; Ponzi et al. 2011). Therefore, the empirical focus on only one group appears contradictory, because it conveys a different theoretical understanding of the concept of corporate reputation. This is an inconsistency in what Dowling (2016) calls the rater entity of reputation.

4.1.5 Theoretical utility

According to Gerring and Christenson (2017), concepts are the components of theories. Hence, they “play a key role within a theory (or theories)” (Gerring and Christenson 2017, p. 34) and are, especially, important for theory development in management (Suddaby 2010). In this respect, it is important to “think about their function within that theory—its theoretical utility—when choosing terms and definitions” (Gerring and Christenson 2017, p. 34). The utility of the concept of reputation for a theory finds a little attention in the research. There are a multitude of different theories with different paradigmatic origins that contribute to the understanding of reputation (Sects. 3.2.1.1, 3.2.2.1). Some of the studies that review and integrate various definitions of corporate reputation make first steps towards the unification of different theoretical perspectives (Ferris et al. 2014; Lange et al. 2011; Rindova et al. 2005; Walker 2010). However, these attempts do not focus on how the concept of reputation may contribute to a higher order theory.

Among a few approaches that take the theoretical utility of the concept of corporate reputation into account is Bitektine’s (2011) social judgment theory. Reputation—just as legitimacy and status—is a form “of social judgment that stakeholders can render with respect to an organization” (Bitektine 2011, p. 152). In a similar vein, Boivie et al. (2016, p. 188) defined reputation as “collective social judgment” by referring to the generalized favorability of a corporation (Lange et al. 2011). A social judgment is “an evaluator’s decision or opinion about the social properties of an organization” (Bitektine 2011, p. 152). In this respect, the assignment of the concept to this theory emphasizes the evaluator’s perspective–reputation results from a judgment formation of the stakeholder. The judgmental orientation can already be found in seminal works in the field (Fombrun 1996; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). It can also be found in the definition on customer-based reputation, which is defined as an “attitude-like evaluative judgment of firms” (Walsh and Beatty 2007, p. 129). Therefore, the following discussion on the formation of a reputation concept is guided by theoretical utility.

As our discussion on the status quo of the corporate reputation concept shows, the criterion internal coherence exhibits the greatest weaknesses. Moreover, a lack of consistency of the reputation concept arises from extant research, and the theoretical utility of corporate reputation has not yet been widely reflected. Two promising approaches—a current review (Dowling 2016) and a conceptual and empirical approach (Schwaiger 2004)—thoroughly examine the issue of lacking fit between definition and measurement of corporate reputation and are discussed in Sect. 4.2. Our discussion is guided by the aim of increasing internal coherence. We also respond to Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) recommendations according to which a purely conceptual view, free from empiricism, is the first necessary step in the formation of a concept. A focus on the evaluator’s perspective seems a promising approach towards a better conceptualization.

4.2 Conceptualizing corporate reputation from an evaluator’s perspective

We draw on the two studies by Dowling (2016) and Schwaiger (2004), because Dowling’s approach resonates with Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) proposed process for concept formation, and the definition by Schwaiger is close to Dowling’s results and, in addition, has already been operationalized.

The recommendation is to begin the process of concept formation by reviewing several definitions and to extract repeated “standard elements” (Gerring and Christenson 2017, p. 35). A comprehensive review of definitions of corporate reputation shows that this holds true for the attributes “beliefs” and/or “evaluation” (Dowling 2016, p. 213). Thus, most definitions see reputation as cognitive or affective evaluations, which, when they coincide, correspond to an attitude (Dowling 2016). Schwaiger (2004) already stresses this aspect by referring to the definition of Hall (1992), who refers to reputation as “knowledge and emotions held by individuals” (Hall 1992, p. 138). Schwaiger (2004, p. 49) puts an emphasis on conceptualizing “corporate reputation as an attitudinal construct” that combines affective and cognitive components “where attitude denotes subjective, emotional, and cognitive-based mindsets”.

After reviewing the existing definitions, Dowling (2016, p. 217) “backwards engineer[s]” a definition with attributes from the RepTrek Pulse measure. However, this backward direction contradicts the recommendation of concept formation (Gerring and Christenson 2017). After extracting the most common attributes of a concept, it is a common approach to formulate a minimal definition with the “specific component of the term that nearly everyone agrees upon” (Gerring and Christenson 2017, p. 37). Hence, this again leads to the idea of the attitudinal construct by Schwaiger (2004). Based on the recommendations for concept formation by Gerring and Christenson (2017), we would advise to adhere to the definition of reputation as an attitudinal construct (with a cognitive and an affective component) that a person holds of an organization. Only after operationalizing and empirically measuring corporate reputation, Schwaiger (2004) reifies the cognitive component as competence and the affective as likeability. Referring to a person, places the concept on an individual level. Dowling (2016) discusses how this resonates with a collective level.

Conceptualizing corporate reputation as an attitudinal concept places a clear focus on the evaluator perspective (Sects. 4.1.2, 4.1.5). An important but underrepresented aspect in the research on corporate reputation is the theoretical utility of this concept. With emphasizing the evaluator perspective, corporate reputation is linked to social judgement theory (Sect. 4.1.5). The focus on attitudinal aspects puts an emphasis on the evaluator at the conceptual level. Reputation results from an evaluation. This evaluation is about the attributes of the corporation. The separation of the attributes of the corporation and the attitudes of the evaluator should positively contribute to the coherence and differentiation of the concept. This makes it easier to distinguish between antecedents and the actual concept. The attributes of the corporation act as evaluation criteria. Corporate reputation, however, is an attitudinal construct resulting from evaluation.

Based on the above reasoning, consistency should be improved. If the concept is more precise (improved internal consistency), it should also be easier to arrive at an operationalization. Therefore, our proposal is to follow Gerring and Christenson (2017) and to make a clear distinction between conceptualization and operationalization with an initial emphasis on issues of conceptualization. In summary, we argue that the emphasis on the theoretical embedding of the concept with a focus on the evaluator can increase the coherence and differentiation and, in turn, the overall consistency of the corporate reputation concept.

5 Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to review research on corporate reputation within management and business studies and to advance the scholarly understanding of the concept. The mere extent of research on reputation in management and business studies suggests that this concept has much resonance in the scholarly community. While available reviews take qualitative approaches with narrative methods, we applied bibliometric methods to arrive at a systematic review. This approach is especially useful when extensive bodies of literature challenge researchers to keep pace with an ever-increasing amount of publications. This is clearly the case with corporate reputation. With a focus on both past traditions and current trends, and supported by network visualizations, we extracted the several maps of research that offer orientation for both experienced scholars in and newcomers to the field. However, despite the higher objectivity and replicability as compared to qualitative reviews, bibliometric methods do not substitute for careful interpretations and evaluations of the findings.

Beyond pioneering bibliometric analyses of the literature on corporate reputation and providing an updated review by including publications until 2016, inclusively, our study also contributes to research in more conceptual terms. While the existing reviews integrate a diversity of different theoretical perspectives (Ferris et al. 2014; Lange et al. 2011; Rindova et al. 2005; Walker 2010), we focus on the utility of the corporate reputation concept for theory building (Sect. 4.1.5). While the misfit between conceptualization and operationalization has already been stressed in the previous studies (e.g., Chun 2005), we offer criteria for concept evaluation from social sciences—which is also in contrast to the review by Dowling (2016)—to advance the concept. Another approach to concept evaluation is taken by Sarstedt et al. (2013), who make use of criterion and convergence validity that focuses on evaluating measurement approaches on reputation, and who also favor the Schwaiger Model (see Sect. 3.2.2.2 for respective results). In their most recent work, Gerring and Christenson (2017) emphasize the distinction between the description of a theoretical concept and the subsequent empirical focus, which seems important for corporate reputation. We suggest re-focusing on the concept itself and addressing potential operationalization only in a second step. In contrast to the previous reviews, we contribute a conceptualization that is guided by theory on the assessment of concepts and concept formation.

Several findings of our bibliometric analysis are worth highlighting. First, we find that corporate reputation research is embedded in a diverse field of research with subject-specific conceptualizations. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to reveal and visualize the ‘big picture’ of research on reputation in the management and business studies.

Second, while our analysis updates and expands on qualitative reviews in terms of covered literature, some of our results confirm the previous findings and assumptions. For example, the results of co-citation analysis reveal the disciplinary origins of corporate reputation research in economics, organizational science, and marketing research, as well as the theoretical heritage of signaling and game theory, RBV, institutional theory, and stakeholder theory. Since this resonates with the reviews by Bergh et al. (2010) and Walker (2010), we are confident that the results of the bibliometric analyses have a high validity. The co-citation method does not only reveal the theoretical foundations but also the importance of neighboring concepts such as image, identity, and status. This is important for the discussion of the differentiation of the corporate reputation concept.

Third, the bibliographic coupling analysis enables us to reveal the core and forefront of research on corporate reputation in a structured manner. The network of bibliographic couplings displays that the current research is predominantly empirical, resulting in evermore new empirical results. On one hand, this leads to an accumulation of attributes and perceptions related to corporate reputation, but, on the other hand, it also leads to a less precise notion of what constitutes corporate reputation as a whole. More theoretically, derived conceptual work could help to advance research on corporate reputation towards integration.

We find that the criterion internal coherence reflects the detected ambiguities in the theoretical and methodological dimension of corporate reputation, while the criterion theoretical utility reveals that reputation as a concept in the field of a higher order theory is less studied. The combination of both allows for a simple yet important conclusion for future research: scholars should clearly distinguish between the attributes of the corporation, on one hand, and the evaluations of the stakeholders, on the other hand. By following Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) advice on concept formation, we recommend focusing on corporate reputation as an attitudinal concept and thereby emphasizing the evaluator’s perspective as theoretical ground. This represents an attempt to overcome deficiencies in coherence, differentiation, consistency, and theoretical utility of the corporate reputation concept. If the reputation concept itself is approached in this manner, a clear distinction should be made in that the attributes of the corporation are not part of the concept itself but rather the criteria of evaluation.

While this is important to achieve the aim of increasing the scholarly understanding of what reputation is, future research can be inspired to investigate how evaluations are formed. For example, Mishina et al. (2012) seek to explore the “socio-cognitive processes that shape the formation of organizational reputations” (p. 460), which is a central aspect in social judgment theory (Bitektine 2011).

Furthermore, we recommend future research to also consider the consistency between the concept of reputation and its operationalization more carefully (see Sect. 4.1.4). The popular definition by Fombrun (1996) combined with the equally popular operationalization based on the Fortune ranking leads to a mismatch.

Limitations should be taken into account for the conceptual evaluation as well as for the bibliometric method. It should be noted that Gerring and Christenson’s (2017) criteria for the assessment of a concept represent a positivistic approach. Gerring admits that “overlapping definitions, internal contradictions between definitional properties, and imprecise operationalizations” (Gerring 1999, p. 392) may be inherent to the formation of concepts in social sciences. Nevertheless, his proposed set of criteria reduces the uncertainty in concept formation.

Although bibliometric methods provide a systematic approach to reviewing literature, they have some limitations worth acknowledging. First, the raw data of bibliometric analyses have to be successively reduced to arrive at high levels of aggregation, which requires researchers to define and apply selection criteria and thresholds. Accordingly, the extracted clusters—and those that remain invisible—in part depend on such technical parameters that are determined by the researchers. Second, bibliometric methods quantify citations without accounting for the intention of the authors’ citation behavior. For example, no distinction can be made between positive (i.e., confirmative) and negative (i.e., critical) citations. However, on a large-scale database and at high levels of aggregation, deviant citation behaviors tend to be marginalized, and positive citations for the purpose of substantiating arguments prove to be predominant. And third, the method of bibliographic coupling tends to overstate works with relatively extensive bibliographies. This is due to the fact that the probability of intersections with other papers (i.e., bibliographic couplings) increases with the amount of references. Another limitation lies in the Scopus Database itself, which predominantly comprises journal articles but less books or book chapters.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our bibliometric review is a reasonable complement to qualitative reviews, because it provides structured and replicable insights into, and overviews of, the foundations and trends in the management research on corporate reputation. Overall, our review shows that corporate reputation is still far from being a uniform concept, leading to a variety of—sometimes unsuitable—operationalizations. Guided by the bibliometric analyses, we provide future research with inspiration to improve conceptual clarity and help in overcoming deficiencies in operationalization.

References

*Denotes studies incorporated in the analysis of Cluster 2

Abraham, M., V. Grimm, C. Neeß, and M. Seebauer. 2016. Reputation formation in economic transactions. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 121: 1–14.

*Abratt, R., and N. Kleyn. 2012. Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate reputations: Reconciliation and integration. European Journal of Marketing 46 (7/8): 1048–1063.

Agrawal, A., and T. Cooper. 2010. Accounting scandals in IPO firms: do underwriters and VCs help? Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 19 (4): 1117–1181.

*Albert, S., and D.A. Whetten. 1985. Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior 7: 263–295.

*Ali, R., R. Lynch, T.C. Melewar, and Z. Jin. 2015. The moderating influences on the relationship of corporate reputation with its antecedents and consequences: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Research 68 (5): 1105–1117.

*Alniacik, E., U. Alniacik, and N. Erdogmus. 2012. How do the dimensions of corporate reputation affect employment intentions? Corporate Reputation Review 15 (1): 3–19.

*Anderson, J.C., and D.W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103 (3): 411–423.

*Ashfort, B.E., and F. Mael. 1989. Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review 14 (1): 20–39.

*Badri, M.A., and J. Mohaidat. 2014. Antecedents of parent-based school reputation and loyalty: an international application. International Journal of Educational Management 28 (6): 635–654.

*Bagozzi, R.O., and Y. Yi. 1988. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Academy of Marketing Science 16 (1): 74–94.

Baka, V. 2016. The becoming of user-generated reviews: Looking at the past to understand the future of managing reputation in the travel sector. Tourism Management 53: 148–162.

*Baldarelli, M., and S. Gigli. 2014. Exploring the drivers of corporate reputation integrated with a corporate responsibility perspective: some reflections in theory and in praxis. Journal of Management and Governance 18: 589–613.

*Balmer, J.M.T. 2009. Corporate marketing: apocalypse, advent and epiphany. Management Decision 47 (4): 544–572.

*Barnett, M.L., J.M. Jermier, and B.A. Lafferty. 2006. Corporate Reputation: The Definitional Landscape. Corporate Reputation Review 9 (1): 26–38.

*Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17 (1): 99–120.

*Baron, R.M., and A.D. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (6): 1173–1182.

*Basdeo, D.K., K.G. Smith, C.M. Grimm, V.P. Rindova, and P.J. Derfus. 2006. The impact of market actions on firm reputation. Strategic Management Journal 27 (12): 1205–1219.

*Beatty, R., and J. Ritter. 1986. Investment banking, reputation and the underpricing of initial public offerings. Journal of Financial Economics 15 (1–2): 213–232.

*Benjamin, B.A., and J.M. Podolny. 1999. Status, quality, and social order in the California wine industry. Administrative Science Quarterly 44 (3): 563–589.

Bergh, D.D., D.J. Ketchen, B.K. Boyd, and J. Bergh. 2010. New frontiers of the reputation-performance relationship: insights from multiple theories. Journal of Management 36 (3): 620–632.

*Bitektine, A. 2011. Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: the case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review 36 (1): 151–179.

Bjørnskov, C., and K.M. Sønderskov. 2013. Is social capital a good concept? Social Indicators Research 114: 1225–1242.

*Black, E.L., T.A. Carnes, and V.J. Richardson. 2000. The Market Valuation of Corporate Reputation. Corporate Reputation Review 3 (1): 31–42.

*Boivie, S., S.D. Graffin, and R.J. Gentry. 2016. Understanding the Direction, Magnitude, and Joint Effects of Reputation When Multiple Actors’ Reputations Collide. Academy of Management Journal 59 (1): 188–206.

Bolton, G.E., B. Greiner, and A. Ockenfels. 2013. Engineering Trust: Reciprocity in the Production of Reputation Information. Management Science 59 (2): 265–285.

Bolton, G.E., E. Katok, and A. Ockenfels. 2004. How effective are electronic reputation mechanisms? An experimental investigation. .Management science 50 (11): 1587–1602.