Abstract

This study derives a conceptual framework for examining parallel and differential influences of organizational pride in employees’ efforts versus abilities on proactivity. Data from a field survey (N = 1218) confirm our theoretical model. Organizational pride in employees’ efforts and organizational pride in employees’ abilities both had positive indirect effects on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment. Yet, whereas organizational pride in employees’ efforts additionally had a direct positive effect on individual and team member proactivity, organizational pride in employees’ abilities showed a direct negative effect on proactive behaviors for the self, the team, and the organization including a behavioral measurement of employees’ provision of ideas for improvement. These findings contribute to the nascent literature on organizational pride by indicating towards employees as source of organizational pride, highlighting potential negative effects of organizational pride, and introducing the differentiation between employees’ efforts and abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“The culture was the secret sauce that made this place great and allowed us to earn our clients’ trust for 143 years. It wasn’t just about making money; this alone will not sustain a firm for so long. It had something to do with pride […] in the organization. I am sad to say that I look around today and see virtually no trace of the culture that made me love working for this firm for many years. I no longer have the pride […].”

(Greg Smith, former Executive Director at Goldman Sachs, 2012)

1 Introduction

In line with the introductory quote, research generally confirms the beneficial consequences of employees’ pride in their organization (Tyler and Blader 2001), which is defined as a collective form of pride resulting from one’s membership in a group (Helm 2013). Taking pride in their organization, employees show more commitment (Tyler and Blader 2002), intend to remain with the organization (Helm 2013), exert proactive and extra-role behaviors (Blader and Tyler 2009), and voice their opinion in favor of the organization (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008). Thus, organizational pride particularly fuels employees’ affective commitment to the organization and motivates employees to deliver more than expected in terms of working harder, taking initiative, and overcoming obstacles (Katzenbach 2003). In light of these consequences, it is not surprising that employees’ organizational pride is seen as a desirable goal for employers.

Aiming to provide indications on how organizational pride can be fostered, prior research showed that it is instilled by factors such as favorable work conditions (Kraemer and Gouthier 2014), volunteer programs (Jones 2010), or an organization’s positive external reputation (Cable and Turban 2003; Helm 2013). Thus, current examinations concentrate on attributes of the organization as sources of organizational pride. Thereby, one important potential source of organizational pride has so far been overseen: Attributes of the organization’s employees. This is the more surprising considering that organizational pride is expected to result from seeing oneself as belonging to a group (Helm 2013), i.e., the employees of an organization, and employees are seen as an important source of organizational performance (Barney 1991). Thus, there appears to be considerable reason for taking organizational pride in employees. Further, when examining employees as antecedents of organizational performance, research differentiates between employees’ motivation, i.e., employees’ intensity, direction, and duration of efforts, and human capital, i.e., employees’ knowledge, skills, and abilities (e.g., Jiang et al. 2012; Liao et al. 2009). Notably, this differentiation includes those dimensions, i.e., efforts and abilities, which have been previously identified as important in eliciting different facets of individual pride (Tracy and Robins 2007a).

Following research on individual pride by differentiating between organizational pride in employees’ efforts and organizational pride in employees’ abilities appears to be crucial because research on individual pride shows that whereas pride in response to attributing positive outcomes to efforts is followed by functional and achievement-related outcomes, pride in response to attributing positive outcomes to abilities is connected with maladaptive and self-aggrandizing outcomes (Tracy and Robins 2007b). In parallel, differentiating between employees’ efforts and abilities for organizational pride may result in differential behaviors. But unlike individual pride, organizational pride is generally expected to be beneficial in organizations because it activates identification processes (Blader and Tyler 2009) resulting from belonging to a positively evaluated group (Tajfel and Turner 1979). These identification processes may be expected for organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities alike because both arise from the positive evaluation of being with one’s employer (Helm 2013).

Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to examine organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities by looking into both parallel and opposing consequences. We focus the examination of these consequences on proactive behaviors, which are generally defined as self-initiated and future-focused efforts to change the self, one’s team or the environment (e.g., Grant et al. 2009) including discrete behaviors such as issue-selling, taking charge and voice (Parker and Collins 2010). We have chosen proactive behaviors because they are highlighted as the beneficial consequences resulting from organizational pride (Katzenbach 2003). Furthermore, the positive relation between organizational pride and proactive behaviors has been explained by identification processes (Blader and Tyler 2009), which additionally renders them suitable for examining both parallel and opposing consequences of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities.

In sum, this research makes the following theoretical contributions. We extend research on the antecedents of organizational pride, which so far detected favorable work conditions (Kraemer and Gouthier 2014), volunteer programs (Jones 2010), and reputation (Helm 2013), by indicating employees’ efforts and abilities as sources of organizational pride. Differentiation between organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities, we also add to research on the consequences of organizational pride, which hitherto only demonstrated positive consequences (e.g., Blader and Tyler 2009; Helm 2013; Tyler and Blader 2002). Specifically, we demonstrate that organizational pride in employees’ abilities can have negative effects on proactive behaviors. Finally, by highlighting employees’ efforts and abilities as attributions leading to different facets of organizational pride, we also connect the nascent research on attribution theory (Martinko et al. 2011) with research on proactive behaviors (Parker and Collins 2010). Next, we derive our hypotheses on parallel and opposing consequences of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Parallel effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities

Building on the communality of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities in arising from positive evaluations, we firstly expect parallel effects of both on proactive behaviors. With proactive behaviors being self-initiated, future-focused, and change-oriented (e.g., Grant et al. 2009), they comprise employees’ discretionary behaviors in situations, in which they may alternatively proceed without immediate consequences such as when solving issues before they become an actual problem (Frese and Fay 2001). Therefore, proactive behaviors are expected to result from innate motivations, which are assumed to be fueled by organizational pride via the process of social identification (Blader and Tyler 2009).

The more positively employees evaluate the organization, i.e., the more organizational pride they experience, the more they feel committed to it (Carmeli 2005). Affective organizational commitment is defined as employees’ emotional attachment, identification, and involvement with the organization (Allen and Meyer 1990). The more committed individuals feel, the more individuals engage in proactive behaviors such as personal initiative, voice, and innovation (Thomas et al. 2010), because they have positive feelings towards the organization (Strauss et al. 2009) and experience a strong sense of ownership (Wang et al. 2014). We expect this mechanism to work independently from taking pride in employees’ efforts or abilities because both facets include a positive evaluation of the organization. Based on social identity theory, we, therefore, expect that organizational pride due to employees’ efforts has a positive indirect effect on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment.

H1a.

Organizational pride in employees’ efforts has a positive indirect relationship with proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment.

And we likewise expect organizational pride due to employees’ abilities to have a positive indirect effect on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment.

H1b.

Organizational pride in employees’ abilities has a positive indirect relationship with proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment.

2.2 Opposing effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities

We base our hypotheses on the opposing effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities on attribution theory (Weiner 1985). According to attribution theory, attributing positive and negative events to effort or ability leads to different consequences, because effort and ability differ in terms of controllability and stability. Whereas efforts are regarded as instable and controllable, abilities are stable and uncontrollable (Weiner 1985). Thus, when events are attributed to efforts, individuals believe that they can influence them, whereas attributing events to ability leads to perceiving them as beyond one’s influence (LePine and Van Dyne 2001).

In line with attribution theory, organizational pride in employees’ efforts can, therefore, be expected to be connected with beliefs about instability and controllability. Perceptions of instability and controllability should particularly reinforce proactive behaviors as these are future-focused and change-oriented (Grant and Ashford 2008). Thus, proactive behaviors aim to overcome current and future barriers and prepare oneself, one’s team or the whole organization for future achievements. Even when being focused on one’s own workspace, they target on improving individual performance, which ultimately benefits the organization (Parker et al. 2006). In sum, individuals taking organizational pride in employees’ efforts should consider proactive behaviors as necessary because performance is expected to be instable, but also as worthwhile because performance is seen as controllable. We, therefore, assume a reinforcing function of organizational pride in employees’ efforts in motivating individuals to reinforce performance by engaging in proactive behaviors.

H2a.

Organizational pride in employees’ efforts has a direct positive relationship with proactive behaviors.

In contrast, organizational pride in employees’ abilities is connected with beliefs about stability and uncontrollability. Therefore, individuals who take pride in their organization because of employees’ abilities should see less need for further changes or challenging the status quo, which is included in proactive behaviors (Fuller et al. 2015), because they consider performance as stable. For them, challenging the status quo may even mean to question the employees’ abilities and the organization itself. Furthermore, proactive behaviors may also be seen as less worthwhile due to perceptions of uncontrollability connected with ability. We, therefore, expect a direct and negative relationship between organizational pride in employees’ abilities and proactive behaviors.

H2b.

Organizational pride in employees’ abilities has a direct negative relationship with proactive behaviors.

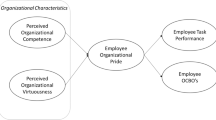

The resulting theoretical model is depicted in Fig. 1. In sum, we expect for organizational pride in employees’ efforts a positive indirect effect via organizational commitment and an additional positive direct effect on proactive behaviors. These effects result in an overall positive effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on proactive behaviors that is partially mediated by organizational commitment. For organizational pride in employees’ abilities, we expect a positive indirect effect via organizational commitment and a negative direct effect on proactive behaviors. These effects may annul each other leading to the overall effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities on proactive behaviors being neither positive nor negative.

3 Method

We tested our hypotheses with employees of a German university. University employees appeared to be a particularly suitable sample because universities are a prototype for knowledge-intensive organizations in which identity work is expected to be particularly important.

3.1 Participants

Overall, 9496 employees received an invitation to participate in the survey. The final sample with analyzable answers for all of the focal variables consisted of 170 professors, 833 scientific employees, and 213 non-scientific employees (2 participants did not indicate their affiliation with one of these groups). Of the resulting 1218 participants, 30.1% were females (10.7% did not indicate their sex), and the average age was approximately 35.6 years (11.7% did not indicate their age).

3.2 Procedure

All measures were collected within an official employee survey, which was conducted to provide feedback on the climate within the organization and employees’ work-related needs for training, professional support, and childcare to the university’s board of management. The survey was anonymously conducted online.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities

The two facets of organizational pride were each measured with two items. Organizational pride in employees’ efforts was measured with “I am proud of this organization because employees in this organization exert a lot of effort” and “I am proud of this organization because employees in this organization work very hard” (α = .85). Organizational pride in employees’ abilities was measured with “I am proud of this organization because employees in this organization possess great abilities” and “I am proud of this organization because employees in this organization are very competent” (α = .91). Answers were provided on seven-point Likert-scales.

In an exploratory principal component analysis with two factors, all four items loaded positively on the first factor, but whereas the effort-related items loaded positively on the second factor, the ability-related items loaded negatively on the second factor. An additional confirmatory factor analysis showed that the one-factor model χ2(2) = 172.92, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.27, TLI = 0.85, CFI = 0.95, produced inferior fit indices than the two-factor model χ2(1) = 0.35, SRMR = 0.00, RMSEA = 0.00, TLI = 1.00, CFI = 1.00, which provided nearly perfect fit indices (West et al. 2012). Finally, discriminant validity can be assumed if the correlation between constructs is not as high as the Cronbach’s alpha for each construct (Rojas-Méndez et al. 2013). The values for Cronbach’s alpha for organizational pride due to employees’ efforts and organizational pride due to employees’ abilities were both higher than the correlation between these constructs (r = .77, p < .001).

3.3.2 Proactive behaviors

Proactive behaviors were measured with two different approaches. First, we used participants’ self-reports of individual (α = .85), team (α = .90), and organizational (α = .91) proactive behaviors (Griffin et al. 2007). Applying a collective translation approach (Douglas and Craig 2007), all of the items were translated by three independent translators. Then, a fourth person compared and consolidated the resulting translations. We slightly modified the wording to the university context. Individual task proactivity was measured with “I initiated better ways of doing my core tasks”, “I came up with ideas to improve the way in which my core tasks are done”, and “I improved the way my core tasks are done”, in which we specified core tasks with research and teaching for professors and research, teaching, and administration for scientific employees. Team proactivity was measured with “I suggested ways to make my work unit more effective”, “I developed new and improved methods to help my work unit perform better”, and “I improved the way my work unit does things,” in which we specified work unit with Chair/research group for professors and scientific employees. Organization-level proactivity was measured with the same items for all employee groups including “I made suggestions to improve the overall effectiveness of the university (e.g., by suggesting changes to administrative procedures),” “I involved myself in changes that are helping to improve the overall effectiveness of the university”, and “I came up with ways of increasing efficiency within the university”. Responses were provided on five-point Likert-scales. Second, because the survey was an official employee survey providing feedback to the university’s management board, it additionally allowed us to take a behavioral measure of proactivity, i.e., employees’ voice in taking part in an organizational suggestion system (Klaas et al. 2012). Within the survey, employees were asked to indicate ideas for improving proactive behaviors within the organization in an open question format. We coded if employees provided an answer to this question resulting in a dummy variable that was 1 if employees indicated ideas for improvement and 0 if none were given.

3.3.3 Affective organizational commitment

Affective organizational commitment (α = .85) was measured with four items taken from the German translation (Schmidt et al. 1998) of the Allen and Meyer (1990) instrument. Three items were taken based on the highest factor loadings; one item was additionally selected due to congruency with the organization’s strategic goals. The resulting four items were “I do not feel emotionally attached to this university”, “This university has a great deal of personal meaning for me”, “I do not feel a strong sense of belonging to my university”, and “I feel like ‘part of the family’ at my university”. Responses were provided on seven-point Likert-scales.

3.3.4 Control variables

In line with the literature on organizational pride (Kraemer and Gouthier 2014), we controlled for gender, age, and organizational tenure as these have been shown to influence proactive behaviors (Griffin et al. 2007; Parker et al. 2006). Due to anonymity requirements, age and tenure were measured in intervals (for age, advancing from below 20 in 10-year steps to over 60; for organizational tenure, advancing from below 5 in 5-year steps to over 40). In addition, we also controlled for positions within the organization, i.e., professors, scientific employees, and non-scientific employees, because hierarchical positions have been shown to influence proactive behaviors (Fuller et al. 2006).

3.4 Data analysis

We first tested the positive indirect and direct effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on proactive behaviors, followed by the examination of the positive indirect effect and the negative direct effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities. Effects on individual, team, and organizational proactivity were examined with OLS regression analyses, effects on ideas for improvement with logistic regression. Indirect effects were examined applying bootstrapping analysis using the SPSS PROCESS syntax with 1000 bootstrap samples (Hayes 2013). Thereby, 1000 data sets are sampled from the original data (Preacher and Hayes 2008) calculating the indirect effect a × b for each data set. The indirect effects are then sorted by size and the lowest and highest 2.5% of the indirect effects are cut off to generate 95% confidence intervals. Indirect effects are significant if the resulting confidence interval does not contain zero (Hayes 2013). For the examination of direct effects, we complemented the analyses with organizational pride in both employees’ efforts and abilities with regressions including only one facet from which the, respectively, other facet was partialled out in a previous step [see Tracy and Robins (2007a) for a similar approach] due to a high correlation between the two facets of organizational pride (r = .77). With the positive indirect and direct effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts resulting in a partial mediation on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment while the positive indirect effect and the negative direct effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities might annul each other, we completed the analyses by testing mediation in terms of changes of the direct effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities on proactive behaviors when including affective organizational commitment in the equation (Baron and Kenny 1986). Because the demographic control variables contained missing values, we performed all analyses with a smaller sample of 1008 participants and additionally report, if significant results change when examining the full sample not including control variables.

4 Results

Table 1 shows means, standard deviations, and correlations for all variables. Regression results on proactive behaviors are depicted in Table 2.

4.1 Effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts

Hypothesis 1a included the positive indirect effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment. Organizational pride in employees’ efforts was positively related with affective organizational commitment (β = .41, p < .01). Further, affective organizational commitment was positively related with individual (β = .10, p < .05), team (β = .12, p < .01), and organizational (β = .15, p < .01) proactivity. In line, significantly positive indirect effects resulted for individual [a × b = .04, 95% CI (.01; .08)], team [a × b = .05, 95% CI (.02; .08)], and organizational [a × b = .06, 95% CI (.03; .10)] proactivity. Yet, affective organizational commitment did not influence the probability to indicate ideas for improvement (B = 0.06, ns). In line, the indirect effect via affective organizational commitment on ideas for improvement was not significant [a × b = .02, 95% CI (− .03; .08)]. Thus, Hypothesis 1a was supported for individual, team, and organizational proactivity; but not for ideas for improvement.

According to Hypothesis 2a, we additionally expected a direct positive relationship between organizational pride in employees’ efforts and proactivity. Results confirmed the hypothesis for individual (β = .10, p < .05) and team (β = .11, p < .05) proactivity. The effect was not significant for organizational proactivity (β = .06, ns) and ideas for improvement (B = − 0.04, ns). When partialling out organizational pride in employees’ abilities from organizational pride in employees’ efforts, results confirmed the reported effects. Significantly positive effects were revealed for individual (β = .07, p < .05) and team (β = .08, p < .05) proactivity; but not for organizational proactivity (β = .05, ns) and ideas for improvement (B = 0.01, ns). Thus, Hypothesis 2a was only supported for individual and team proactivity.

Comparing the indirect effects via affective organizational commitment on proactivity with the effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts when not including affective organizational commitment in the regression, shows for individual and team proactivity that the indirect effect via affective organizational commitment indeed partially mediated the effects of organizational pride in employees’ efforts. For individual (β = .14, p < .01 vs. β = .10, p < .05) and team (β = .15, p < .01 vs. β = .11, p < .05) proactivity, the direct effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts lost in size and significance when including affective organizational commitment in the regression. For organizational proactivity the effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts was significantly positive when not including affective organizational commitment (β = .12, p < .01). As it was no longer significant when including affective organizational commitment in the regression, affective organizational commitment fully mediated the effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on organizational proactivity. The effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on participants’ indication of ideas for improvement was not significant (β = − .02, ns).

4.2 Effects of organizational pride in employees’ abilities

Hypothesis 1b included the positive effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment. Organizational pride in employees’ abilities was positively related with affective organizational commitment (β = .25, p < .01). In line, results showed positive and significant indirect effects for individual [a × b = .03, 95% CI (.01; .05)], team [a × b = .03, 95% CI (.01; .06)] and organizational [a × b = .04, 95% CI (.02; .06)] proactivity. Because affective organizational commitment was not positively related to ideas for improvement, the indirect effect of organizational pride in employees’ efforts on the provision of ideas for improvement via affective organizational commitment was neither significant [a × b = .02, 95% CI (− .02; .06)]. Thus, Hypothesis 1b was supported for individual, team, and organizational proactivity, but not for ideas for improvement.

Hypothesis 2b included the direct negative effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities on proactivity. The direct relationship of organizational pride in employees’ abilities emerged for individual (β = − .10, p < .05), team (β = − .13, p < .05), and organizational proactivity (β = − .11, p < .05). For ideas for improvement, results likewise showed a significantly negative effect (B = − 0.17, p < .05). When partialling out organizational pride in employees’ efforts from organizational pride in employees’ abilities, results also showed significantly negative effects for individual (β = − .07, p < .05), team (β = − .09, p < .01), and organizational proactivity (β = − .07, p < .05). The effect was weaker and only slightly significant for ideas for improvement (B = − 0.12, p < .10). In sum, Hypothesis 2b was supported for all forms of proactivity.

The positive indirect effects and the negative direct effects of organizational pride in employees’ abilities on proactivity might annul each other. When not including affective organizational commitment in the regression, results for organizational pride in employees’ abilities showed no effect on individual (β = −.07, ns) and organizational (β = −.07, ns) proactivity. Significantly negative effects were revealed for team proactivity (β = − .10, p < .05) and ideas for improvement (B = − .15, p < .05). Thus, for individual and organizational proactivity, the positive indirect effect and the negative direct effect indeed annulled each other. For team proactivity, the negative direct effect dominated the positive indirect effect via affective organizational commitment. As results on ideas for improvement did not support a positive indirect effect via affective organizational commitment, the negative direct effect of organizational pride in employees’ abilities was fully effective leading to an overall negative effect.

5 Discussion

Drawing attention to employees as source of organizational pride, we explored the consequences of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities. Both organizational pride in employees’ efforts and organizational pride in employees’ abilities had a positive impact on proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment. But whereas organizational pride in employees’ efforts was in addition directly and positively related with individual and team-oriented proactive behaviors, the direct relation between organizational pride in employees’ abilities and individual, team, and organizational proactivity was negative. Furthermore, organizational pride in employees’ abilities significantly reduced the probability to suggest ideas for improvement within the survey.

5.1 Theoretical implications

These results have three main theoretical implications. First, whereas previous research on organizational pride predominantly looked into attributes of the organization (e.g., Cable and Turban 2003; Helm 2013), this research is the first to look into employees’ efforts and abilities as sources of organizational pride. It confirms that employees indeed experience organizational pride because of employees’ attributes. Thereby, our findings also complement research showing that coworker support and coworker antagonism shape commitment to organizations (Chiaburu and Harrison 2008) by adding coworkers’ efforts and abilities to the list of coworker characteristics influencing an organization’s attractiveness.

Second, although both organizational pride in employees’ efforts and organizational pride in employees’ abilities were positively connected with organizational commitment and thereby, proactive behaviors, they had opposing direct effects on proactive behaviors. Whereas organizational pride in employees’ efforts was positively related with individual and team member proactivity, organizational pride in employees’ abilities was negatively related with proactive behaviors. Although these direct effects were relatively weak, they indicate that organizational pride can indeed have negative effects in seeing one’s organization in too positive lights (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008) and impeding constructive change. This finding is particularly notable as researchers and practitioners alike so far predominantly focused on the advantages of organizational pride.

Third, this study also highlights the pivotal role of attributions of effort versus ability within organizations. Contributing to the nascent research on attribution theory in organizations (Martinko et al. 2011), our findings particularly highlight the role of these attributions with regard to proactive behaviors. As these are inherently connected with efforts (Parker and Collins 2010), future research may benefit from further integrating attribution theory with research on proactive behaviors in organizations.

5.2 Practical implications

Both facets of organizational pride increased proactive behaviors via affective organizational commitment. Thus, organizational pride should be added as antecedent for managing organizational commitment (Morrow 2011). In this vein, managers may be well advised to highlight positive outcomes such as an organization’s positive image (Helm 2013) to instill organizational pride. But because organizational pride due to employees’ efforts was in addition positively related to proactivity, whereas organizational pride due to employees’ abilities showed an additional negative relationship, managers should also make sure to highlight the efforts required to achieve positive outcomes in organizations such as for example when emphasizing efforts and the importance of learning (Murphy and Dweck 2010).

5.3 Limitations and future research

Because this study is the first to look into organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities, it highlights a path for additional research, but also has limitations. Although the results showed that the two facets can be empirically distinguished and have differential consequences, results also showed an overlap between the two facets of pride and relatively small opposing effects. Considering that proactive behaviors are particularly difficult to incentivize and that initiative may make a difference at any point of the work day, even small increases in proactive behaviors may reinforce the achievement of positive organizational outcomes. Nevertheless, qualitative studies asking participants to reflect on why they take pride in their organization might constitute a helpful extension of our approach in examining different bases of organizational pride.

Further research on organizational pride may also separate the employee-related sources of organizational pride, i.e., employees’ efforts and abilities, from the experience of organizational pride in comparing their influence with other antecedents such as work conditions. As we measured organizational pride in employees’ efforts and organizational pride in employees’ abilities as composite instruments, our analyses can only be interpreted with regard to their antecedents, but not concerning the relation between employees’ efforts and abilities with organizational pride.

Although the results were mostly in line with our hypotheses, organizational pride in employees’ efforts did not significantly influence the behavioral measure of proactivity, i.e., employees’ provision of ideas for improvement, whereas its positive effect on scale measures about individual and team level proactivity was supported. One explanation might be that the provision of ideas for improvement, i.e., voice behaviors, does not demand self-initiation from employees to the same extent as other proactive behaviors because employees are directly asked for their opinion. Although this operationalization is in line with current conceptualizations of voice, which likewise include passive forms of employees’ voice (Van Dyne et al. 2003), the fact, that the provision of ideas for improvement was eased in terms of directly asking for anonymous input might have facilitated voice (Klaas et al. 2012). Therefore, additionally reinforcing factors, i.e., organizational pride due to employees’ efforts, played a minor role. But further research that develops a more fine-grained view on different forms of employees’ voice is necessary (e.g., Liang et al. 2012) to understand if different forms of voice are indeed differentially influenced by these antecedents.

Finally, although university employees are the prototype of knowledge workers and organizational commitment is a particularly interesting research area for university employees (Smeenk et al. 2006), additional research in other areas of knowledge work such as for example professional service companies is necessary to extend the generalizability of our findings. In these organizations, indirect managerial control such as instilling pride is assumed to be particularly important because it is more difficult to control employees’ outcomes and quality of work (Alvesson and Willmott 2002). With our data further being cross-sectional, additional studies are particularly necessary to establish causal relationships between organizational pride and both its antecedents and consequences.

6 Conclusions

In summary, this study successfully introduced the conceptualization of organizational pride in employees’ efforts and abilities. The results confirm parallel influences of both on proactive behaviors via organizational commitment, but also direct opposing effects. Thereby, this research provides two important indications for further investigations. First, employees should be considered as potential source of organizational pride. Second, organizational pride can have negative consequences—depending on the factors employees are taking pride in.

References

Allen, N.J., and J.P. Meyer. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology 63: 1–18.

Alvesson, M., and H. Willmott. 2002. Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies 39: 619–644.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120.

Baron, R.M., and D.A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–1182.

Blader, S.L., and T.R. Tyler. 2009. Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extra role behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 445–464.

Cable, D.M., and D.B. Turban. 2003. The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 33: 2244–2266.

Carmeli, A. 2005. Perceived external prestige, affective commitment, and citizenship behaviors. Organization Studies 26: 443–464.

Chiaburu, D.S., and D.A. Harrison. 2008. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 1082–1103.

Douglas, S.P., and C.S. Craig. 2007. Collaborative and iterative translation: An alternative approach to back translation. Journal of International Marketing 15: 30–43.

Frese, M., and D. Fay. 2001. Personal initiative (PI): An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior 23: 133–187.

Fuller, J.B., L.E. Marler, and K. Hester. 2006. Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27: 1089–1120.

Fuller, J.B., L.E. Marler, K. Hester, and R.F. Otondo. 2015. Leader reactions to follower proactive behavior: Giving credit when credit is due. Human Relations 68: 879–898.

Grant, A.M., and S.J. Ashford. 2008. The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 3–34.

Grant, A.M., S. Parker, and C. Collins. 2009. Getting credit for proactive behavior: Supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Personnel Psychology 62: 31–55.

Griffin, M.A., A. Neal, and S.K. Parker. 2007. A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal 50: 327–347.

Hayes, A.F. 2013. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Helm, S. 2013. A matter of reputation and pride: Associations between perceived external reputation, pride in membership, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. British Journal of Management 24: 542–556.

Jiang, K., D. Lepak, J. Hu, and J. Baer. 2012. How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? A meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal 55: 1264–1294.

Jones, D.A. 2010. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 857–878.

Katzenbach, J. 2003. Pride: A strategic asset. Strategy and Leadership 31: 34–38.

Klaas, B.S., J.B. Olson-Buchanan, and A.K. Ward. 2012. The determinants of alternative forms of workplace voice an integrative perspective. Journal of Management 38: 314–345.

Kraemer, T., and M.H.J. Gouthier. 2014. How organizational pride and emotional exhaustion explain turnover intentions in call centers: A multi-group analysis with gender and organizational tenure. Journal of Service Management 25: 125–148.

LePine, J.A., and L. Van Dyne. 2001. Peer responses to low performers: An attributional model of helping in the context of groups. Academy of Management Review 26: 67–84.

Liang, J., C.I. Farh, and J.L. Farh. 2012. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal 55: 71–92.

Liao, H., K. Toya, D.P. Lepak, and Y. Hong. 2009. Do they see eye to eye? Management and employee perspectives of high-performance work systems and influence processes on service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology 94: 371–391.

Martinko, M.J., P. Harvey, and M.T. Dasborough. 2011. Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: A case of unrealized potential. Journal of Organizational Behavior 32: 144–149.

Morrow, P.C. 2011. Managing organizational commitment: Insight from longitudinal research. Journal of Vocational Behavior 79: 18–35.

Murphy, M.C., and C.S. Dweck. 2010. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 36: 283–296.

Parker, S.K., and C.G. Collins. 2010. Taking stock: Integrating and differentiating multiple proactive behaviors. Journal of Management 36: 633–662.

Parker, S.K., H.M. Williams, and N. Turner. 2006. Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 636–652.

Preacher, K.J., and A.F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–891.

Rojas-Méndez, J.I., S.A. Murphy, and N. Papadopoulos. 2013. The US brand personality: A Sino perspective. Journal of Business Research 66: 1028–1034.

Schmidt, K.-H., S. Hollmann, and D. Sodenkamp. 1998. Psychometische Eigenschaften und Validität einer deutschen Fassung des “Commitment”-Frgebogens von Allen und Meyer (1990). [Psychometric properties and validity of a German version of Allen and Meyer’s (1990) questionnaire for measuring organizational commitment.]. Zeitschrift für Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie 19: 93–106.

Smeenk, S.G.A., R.N. Eisinga, J.C. Teelken, and J.A.C.M. Doorewaard. 2006. The effects of HRM practices and antecedents on organizational commitment among university employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 17: 2035–2054.

Smith, G. 2012. Why I am leaving Goldman Sachs. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/opinion/why-i-am-leaving-goldman-sachs.html?pagewanted=all.

Strauss, K., M.A. Griffin, and A.E. Rafferty. 2009. Proactivity directed toward the team and organization: The role of leadership, commitment, and confidence. British Journal of Management 20: 279–291.

Tangirala, S., and R. Ramanujam. 2008. Exploring nonlinearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal 51: 1189–1203.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, C. J. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, William G. Austin, & Stephen Worchel, 33–48, Pacific Grove, California: Brooks/Cole.

Thomas, J.P., D.S. Whitman, and C. Viswesvaran. 2010. Employee proactivity in organizations: A comparative meta-analysis of emergent proactive constructs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 275–300.

Tracy, J.L., and W.R. Robins. 2007a. The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 506–525.

Tracy, J.L., and W.R. Robins. 2007b. Emerging insights into the nature and function of pride. Current Directions in Psychological Science 16: 147–150.

Tyler, T.R., and S.L. Blader. 2001. Identity and cooperative behavior in groups. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 4: 207–226.

Tyler, T.R., and S.L. Blader. 2002. Autonomous vs. comparative status: Must we be better than others to feel good about ourselves? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 89: 813–838.

Van Dyne, L., S. Ang, and I.C. Botero. 2003. Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies 40: 1359–1392.

Wang, Q., Q. Weng, J.C. McElroy, N.M. Ashkanasy, and F. Lievens. 2014. Organizational career growth and subsequent voice behavior: The role of affective commitment and gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior 84: 431–441.

Weiner, B. 1985. An attributional theory of achievement, motivation, and emotion. Psychological Review 92: 548–573.

West, S.G., A.B. Taylor, and W. Wu. 2012. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling, ed. Rick H. Hoyle, 209–231. New York: Guilford.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brosi, P., Spörrle, M. & Welpe, I.M. Do we work hard or are we just great? The effects of organizational pride due to effort and ability on proactive behavior. Bus Res 11, 357–373 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-018-0061-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-018-0061-7