Abstract

Supply chain coordination is enabled by adequately designed contracts so that decision making by multiple actors avoids efficiency losses in the supply chain. From the literature it is known that in newsvendor-type settings with random demand and deterministic supply the activities in supply chains can be coordinated by sophisticated contracts while the simple wholesale price contract fails to achieve coordination due to the double marginalization effect. Advanced contracts are typically characterized by risk sharing mechanisms between the actors, which have the potential to coordinate the supply chain. Regarding the opposite setting with random supply and deterministic demand, literature offers a considerably smaller spectrum of solution schemes. While contract types for the well-known stochastically proportional yield have been analyzed under different settings, other yield distributions have not received much attention in the literature so far. However, practice shows that yield types strongly depend on the industry and the production process that is considered. As consequence, they can deviate very much from the specific case of a stochastically proportional yield. This paper analyzes a buyer–supplier supply chain in a random yield, deterministic demand setting with production yield of a binomial type. It is shown how under binomially distributed yields risk sharing contracts can be used to coordinate buyer’s ordering and supplier’s production decision. Both parties are exposed to risks of overproduction and under-delivery. In contrast to settings with stochastically proportional yield, however, the impact of yield uncertainty can be quite different in the binomial yield case. Under binomial yield, the output uncertainty decreases with larger production quantities while it is independent from lot sizes under stochastically proportional yield. Consequently, the results from previous contract analyses on other yield types may not hold any longer. The current analytical study reveals that, like under stochastically proportional yield, coordination is impeded by double marginalization if a simple wholesale price contract is applied. However, more sophisticated contracts which penalize or reward the supplier can change the risk distribution so that supply chain coordination is possible also under binomial yield. In this context, many contract properties from planning under stochastically proportional yield carry over. Nevertheless, numerical examples reveal that a misspecification of the yield type can considerably downgrade the extent of supply chain coordination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Uncertainties are widely spread in supply chains with demand and supply uncertainties being the most common types. Regarding the supply side, business risks primarily result from yield uncertainty which is typical for a variety of business sectors. It frequently occurs in the agricultural sector or in the chemical, electronic and mechanical manufacturing industries (see Gurnani et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2001; Kazaz 2004; Nahmias 2009). Here, random supply can appear due to different reasons such as weather conditions, production process risks or imperfect input material. In a supply chain context, yield or supply randomness obviously influences the risk position of the actors and, therefore, has an effect on the buyer–supplier relationship in a supply chain. The question that arises is to what extent random yields affect the decisions of the single supply chain actors and the performance of the whole supply chain. In this study, we limit ourselves to a problem setting with deterministic demand. This is to focus the risk analysis of contracting on the random yield aspect which is of practical relevance for production planning in some industries (see Bassok et al. 2002). Except for papers that address disruption risks (e.g., Asian 2014; Hou et al. 2010), all contributions in the field of contract analysis under yield randomness restrict to situations where the yield type is characterized by stochastically proportional random yields. This also holds for a prior work of Inderfurth and Clemens (2014) which considers the coordination properties of various risk-sharing contracts under this type of yield randomness.

The preference for the assumption of stochastically proportional yield is mainly due to the fact that this yield type is relatively easy to handle analytically in standard yield models where only a single production run per period is used for demand fulfillment. In this model context, already the basic analytical studies by Gerchak et al. (1988) and Henig and Gerchak (1990) which investigate the optimal policy structure in a centralized supply chain setting with random yield environment refer to the stochastically proportional yield type. In practice, this form of production yield is only observed if yield losses are caused by an external effect that has a joint impact on a complete production batch so that the yield of each unit in the batch is perfectly correlated. Often, however, other yield types are found (see Yano and Lee 1995) which are of greater practical relevance and demand for specific consideration in decision making and contract analysis. Literature contributions which refer to a larger variety of yield models concentrate on planning situations where multiple production lots within a single period can be released [see (Grosfeld-Nir and Gerchak 2004) for an overview]. These studies, however, only address centralized decision making problems.

In our study, we focus on problems with a single production run and deviate from the assumption of stochastically proportional yield. Instead, we study a framework with binomially distributed yield which is characterized by a zero yield correlation of units within a production batch. This yield property is observed if failures in manufacturing operations or if material defectives occur independently in a production process. Since the properties of stochastically proportional and binomial yield are contrary (perfect vs. zero yield correlation), it is by no means straightforward if the coordination properties of contracts hold for both yield types in the same way. This paper is the first one that addresses the analysis of coordination by contracts under binomial yield conditions and investigates to which extent the results for stochastically proportional yields in Inderfurth and Clemens (2014) carry over to a situation where yields are binomially distributed.

In this context, the main purpose of this paper is to study how contracts can be used to diminish profit losses which are driven by uncoordinated behavior. Therefore, three different contracts are applied and analyzed regarding their coordination ability, namely the simple wholesale price contract, a reward contract [overproduction risk-sharing contract, first introduced by He and Zhang (2008)] and a penalty contract (compare Gurnani and Gerchak 2007). Comparable to the newsvendor setting with stochastic demand but reliable supply, the double marginalization effect of the wholesale price contract is found in our setting. Both advanced contract types can be shown to facilitate supply chain coordination if contract parameters are chosen appropriately.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 the supply chain model and the yield distribution are introduced. In part 3 the centralized supply chain is analyzed in a binomial yield setting to generate a benchmark for decisions and objective values in the following contract analyses. Section 4 describes three contract designs, namely the wholesale price contract, the overproduction risk sharing contract, and the penalty contract and analyzes them with respect to their supply chain coordination potential. Section 5 summarizes main results, highlights problems caused by yield misspecification and suggests aspects of further research.

2 Model and assumptions

This paper considers a basic single-period interaction within a serial supply chain with one buyer (indicated by B) and one supplier (indicated by S). It is assumed that all cost, price, and yield information is common knowledge. In contrast to that, deterministic end-customer demand is not common knowledge but only known to the buyer. As the supplier decision is totally independent from end-customer demand, this is a reasonable assumption. This setting connects to the field of contracting in a principal-agent context with information asymmetry [see (Corbett and Tang 1999) or (Burnetas et al. 2007)] where the principal (buyer) is better informed than the agent (supplier). Nevertheless, this property has no effect on the agent’s profit because it is not a direct function of the principal’s information on demand (compare Maskin and Tirole 1990). The supply chain and the course of interaction (explained below) are depicted in Fig. 1.

Assume the above two-member supply chain (indexed by SC). End-customer demand is denoted by D. The buyer orders from the supplier an amount of X units. The production process of the supplier, however, underlies risks which lead to random production yields, i.e., although the production input is fixed the output quantity in a specific production run is uncertain. The supplier can, due to production lead times, realize only a single production run.

In the following, production yield is denoted by \(Y(Q)\) where \(Q\) is the production input chosen by the supplier. The quantity delivered to the buyer is the minimum of order quantity and production output. Hence, the supplier faces the risk of losing sales in case of too low production yield. However, it is a reasonable assumption that, given a simple wholesale price contract, the supplier is not further penalized (in addition to losing potential revenue) if end-customer demand cannot be satisfied due to under-delivery. In typical business transactions the supplying side is usually measured in terms of its ability to deliver to the buyer and not to the end customer. As the mechanism to satisfy end-customer demand is not in the control of the supplier, she cannot be held responsible for potential sales losses. However, both actors face the risk of lost sales because under-delivery by the supplier can cause unsatisfied demand at the buyer as stated above. Consequently, both parties may have incentives to inflate demand (from the buyer’s perspective) or order quantity (from the supplier’s perspective) to account for the yield risk and avoid lost sales. In case production output is larger than order quantity, excess units are worthless and cannot generate any revenue even though they incurred production cost. Sales at the buyer are the minimum of delivery quantity and end-customer demand. If the buyer’s order and delivery quantity exceed demand, excess units are also of no value and cannot be turned into revenues.

Production yields are assumed to be binomially distributed, i.e., a unit turns out ‘good’ (or usable) with success probability \(\theta\) (\(0 \le \theta \le 1\)) and it is unusable with counter probability \(1 - \theta.\)

Thus, the probabilities for possible yields from a production batch Q are given by

Mean production yield amounts to

with a standard deviation of

Note that the coefficient of variation \(({{\sigma_{Y(Q)} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sigma_{Y(Q)} } {\mu_{Y(Q)} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\mu_{Y(Q)} }} )\) decreases as the input quantity grows, i.e., the risk diminishes with increasing production quantity. This is different from a situation with stochastically proportional yield where production yield is a random fraction of production input and neither mean nor variance of the yield rate depends on the batch size. Thus, a reasonable conjecture is that under binomially distributed yields, the risk allocation between the single actors is different from that under stochastically proportional yields. Hence, contract schemes with different risk-sharing mechanisms may perform differently when the lot size influences the “amount of risk” in the supply chain and may change the proposed contract types’ coordination efficiency. The subsequent analyses will shed light on this issue.

For large values of demand (like for most consumer goods) and the respective production quantity, i.e., if the sample of the binomial distribution is sufficiently large, according to the De Moivre–Laplace theoremFootnote 1 the binomial distribution can be approximated through a normal distribution. This approximation will be used in the sequel with parameters which are fitted according to (1) and (2).Footnote 2 This deviation from the exact binomial distribution is motivated by the fact that it facilitates the contract analysis by modeling the decision problem with continuous instead of discrete variables so that general analytic results with closed-form expressions can be derived. Furthermore, the respective numerical results are very close to optimal under fairly high demand levels.

Further notation is as follows:

- c :

-

Production cost (per unit input)

- w :

-

Wholesale price (per unit)

- p :

-

Retail price (per unit)

- \(f_{S} \left( \cdot \right)\) :

-

pdf of standard normal distribution

- \(F_{S} \left( \cdot \right)\) :

-

cdf of standard normal distribution

- \(f_{Y(Q)} \left( \cdot \right)\) :

-

pdf of random variable \(Y(Q)\) (yield)

- \(F_{Y(Q)} \left( \cdot \right)\) :

-

cdf of random variable \(Y(Q)\) (yield)

The problem which arises is how to determine quantities for ordering on the one hand (by the buyer) and choosing a production input quantity on the other hand (by the supplier) given the risks mentioned above. The general underlying assumption in this analysis is that profitability of the business for both parties is assured, i.e., the retail price \(p\) exceeds the wholesale price \(w\) which in turn exceeds the expected production cost \(c/\theta\), i.e., \(p > w > c/\theta\). As is common in the field of contract analysis, the behavior of the actors in a supply chain is investigated under the assumption that decentralized decision making can be modeled as a Stackelberg game. Before we come to the respective analyses, first the optimal decisions will be evaluated for a centralized supply chain setting to provide a benchmark solution.Footnote 3

3 Analysis for a centralized supply chain

Under centralized decision making, the planner has only one decision to make, namely the production input quantity \(Q .\) Revenues are generated from selling the available quantity, i.e., the minimum of production output and demand, to the end customer. Production cost, however, is incurred for every produced unit. Thus, the total supply chain profit is given by

The first term in (3) describes the expected revenue from selling usable units; the second part constitutes the costs which are incurred by the respective production quantity. For deriving the optimal decision on production input, two cases have to be analyzed separately: \(Q \le D\) and \(Q \ge D.\)

Case SC(I)

Under case SC(I) \((Q \le D)\) it is obvious that \(Y(Q) \le Q \le D\), due to \(0 \le \theta \le 1.\) Thus, the supply chain profit transforms to

Taking the first-order derivative yields

For case SC(I), it follows that the supply chain produces the following quantity

If the condition for profitability of the business holds, i.e., \(p > c/\theta\), it has to be evaluated whether an input quantity \(Q \ge D\) is preferable.

Case SC(II)

In this case \((Q \ge D)\) the supply chain profit to maximize is given in (3). In this function the expected sales quantity of the supply chain will be denoted by L (D, Q) and can be expressed by

Transforming this expression under the normality assumption for Y(Q) yields

Here we define \(z_{D,Q} : = \frac{{D - \mu_{Y(Q)} }}{{\sigma_{Y(Q)} }}\). Note that \(z_{D,Q}\) depends on demand \(D\) as well as on production input \(Q\) through mean and standard deviation of the yield \(Y(Q)\). Thus, the above supply chain profit transforms to

Taking the first-order derivative yields

The second-order derivative turns out to be negative so that the profit function in (6) is concave. Thus, we can utilize the first-order condition \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{\rm SC} \left( Q \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{\rm SC} \left( Q \right)} {{\text{d}}Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}Q}}\mathop { \, = \, }\limits^{!} 0\) to derive the optimal input decision for case SC(II). The respective production quantity results implicitly from the following optimality condition

and is denoted by \(Q_{\text{SC(II)}}\). If we define

and \(z_{D,Q}\) as above, the optimality condition for \(Q_{\text{SC(II)}}\) can be re-formulated as

3.1 Overall solution

Since the solution space of case SC(II) includes the solution from (4) for \(p > c/\theta\), the overall production decision of the supply chain is given by

The corresponding optimal profit of the supply chain results from (6) and takes the following form:

with \(\mu_{Y(Q)}^{*} = \mu_{{Y(Q^{*} )}}\), \(\sigma_{Y(Q)}^{*} = \sigma_{{Y(Q^{*} )}}\), and \(z_{D,Q}^{*} = \frac{{D - \mu_{Y(Q)}^{*} }}{{\sigma_{Y(Q)}^{*} }}.\)

Inserting \(\sigma_{Y(Q)}^{*} \cdot f_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) = 2 \cdot F_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) \cdot \mu_{Y(Q)}^{*} - \frac{2 \cdot c}{p \cdot \theta } \cdot \mu_{Y(Q)}^{*}\) which is given from (7) and (8) and exploiting \(\mu_{Y(Q)}^{*} = \theta \cdot Q^{*}\) yields the optimal supply chain profit

To analyze the relationship between production quantity and demand, the derivative \({{{\text{d}}Q\left( D \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}Q\left( D \right)} {{\text{d}}D}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}D}}\) is evaluated. The relation between \(Q\) and \(D\) is given by

which shows that larger demand leads to larger production quantities which is intuitive. Interestingly, the production/demand ratio \((Q/D)\) converges to a constant the larger demand gets. Assuming that demand approaches infinity, it can be shown that the production quantity approaches demand multiplied by \(1/\theta.\) This means that production is only inflated to compensate for expected yield losses, but no further adjustment is made to account for the yield risk. This is reasonable as binomially distributed yields decrease in risk as the input quantity rises (noting that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{Q \to \infty } \left( {{{\sigma_{Y(Q)} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sigma_{Y(Q)} } {\mu_{Y(Q)} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\mu_{Y(Q)} }}} \right) = 0\)). Generally, we can formulate the following Lemma:

Lemma

If demand approaches infinity, the inflation factor of demand for the production input, i.e., \(Q/D\), approaches \(1/\theta.\)

However, there is no unique way how the \(Q/D\) ratio is approaching \(1/\theta\) as demand grows. Rather, it depends on the value of demand, production cost, retail price, and success probability whether the ratio is increasing from below \(1/\theta\), decreasing from above \(1/\theta\) or takes a combination of both. "Examples for the development of the production/demand ratio" in Appendix shows respective numerical examples.

4 Contract analysis for a decentralized supply chain

A decentralized supply chain consists of more than one decision maker. In our setting, a single buyer decides on the order quantity to fill end-customer demand and a single supplier produces to satisfy the order from the buyer as described in the beginning. The decentralized supply chain is modelled as a Stackelberg game with the buyer being the leader and the supplier being the follower, i.e., the buyer anticipates the production decision by the supplier in reaction to his order. In this context, it is assumed that the buyer has knowledge of the supplier’s yield distribution and production cost.

Following the above decision making process, each of the considered contract types is analyzed in three steps. First, the supplier’s optimal production decision for a given buyer’s order volume is analyzed. Second, the buyer’s decision is evaluated that maximizes his profit under anticipation of the supplier’s production response. Third, it is investigated if and under which specific conditions the interaction of buyer and supplier is able to lead to the first-best result from the centralized supply chain so that coordination is achieved. This three-step analysis will first be carried out for the standard wholesale price contract before it is extended to two contracts (overproduction risk sharing contract and penalty contract) which are known to coordinate the supply chain in the case of stochastically proportional production yield.

4.1 Wholesale price contract

Under a simple wholesale price (WHP) contract the buyer orders some quantity X, and the supplier releases a production batch \(Q.\) The output from this batch is used to satisfy the buyer’s order to a maximum extent. Delivered units are sold to the buyer at a per unit wholesale price \(w.\) In the context of this analysis the price \(w\) which rules the distribution of supply chain profits is a given parameter. In the following, the decisions made by the supplier and by the buyer are analyzed separately.

4.1.1 Supplier decision

Given the buyer’s order quantity \(X\), the supplier maximizes the following expected profitFootnote 4:

The first term in (12) describes the expected revenue from selling usable units to the buyer; the second term represents the corresponding production cost. According to their implication for the supplier’s profit function, two cases (\(Q \le X\) and \(Q \ge X\)) are considered separately.

Case S(I)

Under case S(I) \((Q \le X)\) it holds that \(Y(Q) \le Q \le X\) due to \(0 \le \theta \le 1\), and the supplier faces a profit of

The first-order derivative

is positive if \({\text{w}} > c/\theta\) and zero or negative otherwise. This implies the following production decision

If the condition for profitability of the business holds, i.e., \(w > c/\theta\), it has to be evaluated whether \(Q \ge X\) is preferable for the supplier.

Case S(II)

In this case \((Q \ge X)\) the supplier’s profit to maximize is the one in (12) which after some transformation is given by

Here, we define the delivery quantity from the supplier to the buyer as

and \(z_{X,Q} : = \frac{{X - \mu_{Y(Q)} }}{{\sigma_{Y(Q)} }}.\) The optimal production input for case S(II) results from the first-order condition below:

with

which is independent from any cost or price parameter. The optimal input quantity under case S(II) is denoted by \(Q_{\text{S(II)}}^{\text{WHP}}\) and satisfies the optimality condition below

Theoretically, the supplier can choose a production quantity which is smaller than the order quantity and generate positive profits. However, in this case the optimization will follow case S(I), the solution of which is included in the solution space of S(II). Summarizing, the supplier’s production decision under the simple WHP contract is given by

The supplier’s profit is concave as the second-order derivative is negativeFootnote 5:

Analogously to the centralized supply chain analysis, the relation between \(Q\) and \(X\) is given byFootnote 6

4.1.2 Buyer decision

The buyer as the leader in this Stackelberg game anticipates the supplier’s decision from (19). As first mover, under a simple WHP contract the buyer maximizes the following expected profit:

The first term of this profit function is the expected revenue from selling to the end customer; the second term describes the expected cost from procuring units from the supplier. Also for the buyer decision, depending on the order/demand relationship (\(X \le D\) or \(X \ge D\)), two cases for the profit function have to be distinguished.

Case B(I)

Under case B(I) \((X \le D)\) the buyer’s profit is given by

The first-order derivative is rather complex as the buyer is the leader in this Stackelberg game and accounts for the supplier’s reaction to his decision, i.e., \(Q = Q^{\text{WHP}} \left( X \right).\) Therefore, the total first-order derivative of this function includes the relation \({\text{d}}Q\left( X \right)/{\text{d}}X\) from (20) which describes the change in production input given a change in order quantity. The total first-order derivative is given by

Given the partial first-order derivative \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial X}}\) [with \(L\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (16)] as

the total first-order derivative of the buyer’s profit is derived from the following partial derivatives below

with \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial Q}}\) from (17).

After inserting these terms, the total first-order derivative turns out to be

Due to \(M\left( {X,Q} \right) > 0\), \({\text{d}}Q\left( X \right)/{\text{d}}X > 0\), and the profitability assumption \(p > w\) it follows that \(X^{\text{WHP}} = D\) because

The order decision under case B(I) is formulated below

Case B(II)

Analyzing the second case B(II) \((X \ge D)\), the buyer’s profit is given by \(\varPi_{B}^{\text{WHP}} \left( X \right) = p \cdot E\left[ {\hbox{min} \left( {D,Y\left( Q \right)} \right)} \right] - w \cdot E\left[ {\hbox{min} \left( {X,Y\left( Q \right)} \right)} \right]\) or, equivalently,

As under case B(I), the first-order derivative is given by

The single terms can be expressed as

and

with \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial X}}\) from (24) and \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial Q}}\) from (17).

Finally, the total first-order derivative is given by

Exploiting this derivative, the buyer decision under case B(II), denoted by \(X_{\text{B(II)}}^{\text{WHP}}\), is implicitly given from the first-order condition \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\text{WHP}} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\text{WHP}} \left( X \right)} {{\text{d}}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}X}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0\). Hence, as the order decision under case B(II) includes the solution of case B(I), the overall order decision under the WHP contract is formulated below

4.1.3 Interaction of buyer and supplier

To evaluate the coordination ability of the WHP contract it has to be analyzed whether a wholesale price value exists which induces the supplier to produce the supply chain optimal quantity Q * chosen in the centralized setting. In a second step it must be checked if a coordinating wholesale price leaves each supply chain actor with a positive profit so that both of them have an incentive to participate in the business.

The following analysis shows that two extreme wholesale price values (\(w = p\) and \(w = c/\theta\)) exist which formally meet the coordination condition but violate the participation constraints.

(I) Wholesale price \(w = p\)

From the supply chain’s and the supplier’s optimality conditions in (8) and (18) we know that \(\frac{c}{p} = M\left( {D,Q^{*} } \right)\) and \(\frac{c}{w} = M\left( {X,Q^{\text{WHP}} } \right)\), respectively, if \(p > w > {c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c \theta }} \right. \kern-0pt} \theta }.\)

Coordination is achieved if \(Q^{\text{WHP}} = Q^{*}\). Obviously, this is guaranteed if the following two conditions hold: (i) the buyer orders at demand level \((X^{\text{WHP}} = D)\) which yields \(M\left( {X,Q^{\text{WHP}} } \right) = M\left( {D,Q^{*} } \right)\) and (ii) the wholesale price is equal to the retail price which guarantees that \({c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c p}} \right. \kern-0pt} p} = {c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c w}} \right. \kern-0pt} w}.\) Given \(w = p\), the effect on the buyer’s profit has to be evaluated. Under case B(II) \((X \ge D)\), the first-order derivative of the buyer profit in (27) transforms to

Thus, for all values of the buyer’s order in the range \(X \ge D\), his marginal profit is negative. Consequently, the buyer will not order above end-customer demand. Evaluating the decision spectrum \(X \le D\), the buyer profit from (22), given \(w = p\), turns out to be zero:

Because the buyer’s profit is zero for any order quantity below end-customer demand, he is indifferent between all values from 0 to \(D\). Assuming that the buyer orders \(X^{\text{WHP}} = D\) units and given \(w = p\), it follows from the supply chain’s and the supplier’s profits in (6) and (15) that

Thus, the supplier receives the total supply chain profit while the buyer does not generate any profit when ordering D units. Hence, the buyer does not agree on the contract and the business does not take place at all. Consequently, coordination cannot be achieved by the simple wholesale price contract if the two above conditions hold. The buyer only participates in the business if the wholesale price is below the retail price. However, in this case it holds that \({c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c p}} \right. \kern-0pt} p} < {c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c w}} \right. \kern-0pt} w}\) and, consequently, \(M\left( {X,Q^{\text{WHP}} } \right) > M\left( {D,Q^{*} } \right).\) As \({{\partial M\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial M\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial Q}} < 0\), it follows that the supplier’s production quantity is too low to coordinate the supply chain. Only a wholesale price value as large as the retail price incentivizes the supplier to produce the supply chain optimal quantity when the buyer’s order equals demand.

(II) Wholesale price \(w = c/\theta\)

However, a low wholesale price might induce the buyer to order larger amounts which compensate the unwillingness of the supplier to inflate the order enough to reach the supply chain optimum. For that reason, another extreme case for the wholesale price is evaluated.

If the supplier sells at her expected production cost to the buyer \((w = c/\theta)\), it is obvious that a production quantity larger than the order quantity makes no sense. Thus, case S(I) \(Q \le X\) must be analyzed with the profit function from (13). Setting \(w = c/\theta\) yields

Because the supplier’s profit is zero for all possible production choices, she is indifferent between all values from 0 to \(X^{\text{WHP}}.\) That being the case, it will be assumed that the supplier produces \(Q^{\text{WHP}} = X^{\text{WHP}}\) units. Anticipating this behavior, the buyer maximizes his profit for case B(II) \(X \ge D\) in (26)

Given \(Q^{\text{WHP}} = X^{\text{WHP}}\), it follows that \(F_{S} \left( {z_{X,Q} } \right) = 1\) and \(f_{S} \left( {z_{X,Q} } \right) = 0\). Thus, the buyer’s profit function transforms to

because according to (5) \(w \cdot L\left( {X,Q} \right) = \frac{c}{\theta } \cdot L\left( {X,Q} \right) = \frac{c}{\theta } \cdot Q + \frac{c}{\theta } \cdot \left( {1 \cdot \left( {Q - \theta \cdot Q} \right) + \sigma_{Y(Q)} \cdot 0} \right) = c \cdot Q\) is given.

As \(X^{\rm WHP} = Q^{\rm WHP}\) and \(\varPi_{B}^{\rm WHP} \left( {X^{\rm WHP} \left| {Q^{\rm WHP} = X^{\rm WHP} } \right.} \right) = \varPi_{\rm SC} \left( Q \right)\), it obviously follows that \(X^{\rm WHP} = Q^{*}\) and \(\varPi_{B}^{\rm WHP} \left( {X^{\rm WHP} } \right) = \varPi_{\rm SC} \left( {Q^{*} } \right).\)

Thus, it can be shown that given \(w = c/\theta\), coordination of the supply chain could be enabled with the buyer ordering the supply chain optimal production quantity and the supplier producing the exact order quantity. However, as the supplier is left with no profit, her participation constraint is violated and she does not agree on the contract. Thus, coordination of the supply chain is impeded by violating the supplier’s participation constraint.

Summarizing, each case violates the participation constraint of one actor in the supply chain (\(\varPi_{B}^{\rm WHP} \left( X \right) = 0\) for \(w = p\) and \(\varPi_{S}^{\rm WHP} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right) = 0\) for \(w = c/\theta\)) and, thus, terminates the interaction.

4.2 Overproduction risk-sharing contract

Under the overproduction risk-sharing (ORS) contract, the risk of producing too many units (i.e., those units which exceed the order quantity) is shared among the two parties. Thus, the supplier bears less risk and is motivated to respond to the buyer’s order with a higher production quantity. Under this contract, the buyer commits to pay for all units produced by the supplier. While he pays the wholesale price \(w\) per unit for deliveries up to his actual order volume, quantities that exceed this amount are compensated at a lower price \(w_{0}.\) To exclude situations where the supplier will generate unlimited profits from overproduction the following parameter restrictions are set: \(w_{0} < c/\theta < w.\) As the supplier is able to generate revenue for every produced unit she has an incentive to produce a larger lot compared to the situation under the simple WHP contract. This increase might provide the potential to align the supplier’s production decision with the supply chain optimal one.

In this context, two contract variants have to be distinguished depending on the way a possible overproduction is handled by the parties. Under the first variant the buyer just financially compensates the supplier for overproduction without physically receiving deliveries that exceed his order size. This Pull-ORS contract leaves him in a different risk position as when the parties agree that the supplier will deliver the whole production output irrespective of the buyer’s order. This variant is denoted as a Push-ORS contract.

4.2.1 Supplier decision

The profit to optimize by the supplier is identical for both contract variants. Different from the WHP profit function in (12) it includes the compensation for overproduction and is given by

Like in the WHP contract analysis, two cases are analyzed separately, S(I) \((Q \le X)\) and S(II) \((Q \ge X).\)

Case S(I)

From case S(I) \((Q \le X)\) it results that \(Y(Q) \le Q \le X\) and the supplier’s profit transforms to

For the first-order derivative it holds that

From that, the optimal input decision under case S(I) is given by

Consequently, it has to be evaluated whether case S(II) \((Q \ge X)\) is preferable for the supplier.

Case S(II)

In this case, the supplier profit is given by

so that we can formulate

with \(L\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (16). The first-order derivative of the supplier’s profit is given by

with \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial Q}}\) from (17). The supplier’s production quantity under case S(II), \(Q_{\text{S(II)}}^{\text{ORS}}\), results from the first-order condition \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{S}^{\text{ORS}} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{S}^{\text{ORS}} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right)} {{\text{d}}Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}Q}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0\) and is implicitly given from:

Thus, the supplier’s production decision under an ORS contract can be formulated as

Note that for \(w_{O} = 0\) the optimal decision is identical to that under a WHP contract.

The supplier’s profit is concave as the second-order derivative is negative:

Since \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) in (34) is a constant like for the WHP contract, the first-order derivative \({{{\rm d}Q^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}Q^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\) is identical to that in (20).

4.2.2 Buyer decision

The buyer’s profit function depends on the specific type of ORS contract that is applied. Under a Pull-ORS type (exclusion of over-delivery) the buyer maximizes a profit which compared to the WHP contract is reduced by the supplier’s compensation for overproduced items

As for the supplier, the buyer analysis treats two separate cases.

Case B(I)

Under case B(I) \((X \le D)\), the buyer’s profit is given by

which delivers

The total first-order derivative of (37) is given by

with \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (17) and \({{{\rm d}Q\left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}Q\left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\) from (20). Depending on whether the first-order derivative is positive or negative, the order quantity under case B(I), \(X_{B(I)}^{\rm ORS}\), ranges from zero up to demand D.

Case B(II)

For case B(II) \((X \ge D)\) the buyer maximizes the following profit

that equals

with \(L\left( {D,Q} \right)\) from (5) and \(L\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (16). The profit maximizing order quantity for case B(II), \(X_{B(II)}^{\rm ORS}\), results from the first-order derivative below

with \(M\left( {D,Q} \right)\) and \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (7) and (17), respectively, by setting \({{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0.\)

4.2.3 Interaction of buyer and supplier

Under the extended contract with two parameters w and w 0 it has to be analyzed whether there exists a combination of contract parameters which guarantees that the total supply chain profit is maximized while both, supplier and buyer, accept the contract. Coordination is achieved if the optimality conditions of supply chain and supplier under an ORS contract are identical. They are given from (8) and (34), respectively:

This condition is fulfilled if (i) the buyer orders at demand level, i.e., if \(X^{\rm ORS} = D\) and (ii) \(M\left( {D,Q^{*} } \right) = M\left( {X,Q^{\rm ORS} } \right)\) holds, i.e., if the following condition for the contract parameters is satisfied

which ensures that \({c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c p}} \right. \kern-0pt} p} = {{\left( {c - w_{0} \cdot \theta } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {c - w_{0} \cdot \theta } \right)} {\left( {w - w_{0} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {w - w_{0} } \right)}}.\) This condition also implies that \(p = {{\left( {w - w_{0} } \right) \cdot c} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {w - w_{0} } \right) \cdot c} {\left( {c - w_{0} \cdot \theta } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {c - w_{0} \cdot \theta } \right)}} > w - w_{0}.\)

For this parameter setting the supplier’s marginal profit under case S(II) in (33) turns out to be

The supplier’s marginal profit being zero, shows that the supplier actually chooses the respective quantity. As the buyer anticipates this behavior, it can be evaluated which order decision maximizes the buyer’s profit. Under case B(II) \((X \ge D)\), for \(Q^{\rm ORS} = Q^{*}\) the buyer’s marginal profit from (40) transforms to

Due to the first-order derivative being negative, the buyer will not order above demand. Assuming an order quantity of \(X^{\rm ORS} = D\) and the coordinating parameter setting from (41), the buyer maximizes the profit under case B(I) \((X \le D)\) in (37) according to

Rearranging the above profit yields:

Due to (41) it holds that \(p > w - w_{0}\) and thus, \(\varPi_{B}^{\rm ORS} \left( {X^{\rm ORS} = D} \right) > 0.\) Utilizing the first-order condition of the above profit, the optimal order quantity is determined. The relation in (42) allows us to conclude that \({{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm ORS} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}} > 0\) since \({{{\rm d}\varPi_{\rm SC}^{*} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}\varPi_{\rm SC}^{*} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}} > 0\) (with \(\varPi_{\rm SC}^{*} \left( X \right) = \varPi_{\rm SC}^{*}\) for \(D = X\)) and thus, \(X^{\rm ORS} = D.\)

So, both conditions for coordination are fulfilled which proves that the Pull-ORS contract can enable supply chain coordination, because the buyer incentivizes the supplier to produce the supply chain optimal amount by ordering at demand level if the contract parameters are fixed appropriately, i.e., according to (41).

If the actors agree on a Push-ORS contract the situation changes. In case all produced items are physically delivered, the buyer’s sales are not restricted by his own order and his profit turns out to be identical for the cases B(I) and B(II), i.e., for \(X \le D\) and \(X \ge D\), and is given from (39):

From the previous analysis of the interaction between supplier and buyer, it is given that coordination requests \(X^{\rm ORS} = D\) and \(c \cdot \left( {w - w_{0} } \right) = p \cdot \left( {c - w_{0} \cdot \theta } \right).\) These conditions result in the following marginal profit for the buyer:

As the buyer’s marginal profit is negative (given \(w_{0} < w\)), it is no option for the buyer to order at demand level. Through the design of the contract, orders below demand may be optimal. As the delivered quantity can exceed the order or even end-customer demand, the buyer can still meet demand by ‘under-ordering’. Assuming the buyer orders below demand, there may be combinations of \(w\) and \(w_{0}\) which incentivize the supplier to produce the supply chain optimal quantity (obviously, a larger wholesale price or a higher compensation for overstock is necessary). However, higher prices are less profitable for the buyer who would further reduce his order quantity. This downward trend continues until nothing is ordered at all. Thus, the Push-ORS contract cannot coordinate the supply chain.

4.3 Penalty contract

If a penalty (PEN) contract is applied the supplier will bear a higher risk than under a simple WHP contract since she is punished for under-delivery. The supplier is penalized by the buyer (in the amount of \(\pi\)) for each unit ordered that cannot be delivered because of insufficient production yield. Given the potential penalty the supplier has an incentive to produce more than under the simple WHP contract which might be sufficient to achieve coordination of the supply chain.

4.3.1 Supplier decision

Under the PEN contract, the profit to optimize by the supplier includes the revenue from product delivery as well as a penalty for under-delivery and is given by

In the following, the two cases S(I) \((Q \le X)\) and S(II) \((Q \ge X)\) are, again, analyzed separately.

Case S(I)

Given case S(I) \((Q \le X)\) the supplier’s profit simplifies to

From the first-order derivative of (44) which is given by

it follows that the supplier produces either zero or the ordered amount depending on the parameter constellation as formulated below

Note that if \(Q = X\), then \(\varPi_{S}^{\rm PEN} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right) = \left( {\left( {w + \pi } \right) \cdot \theta - c - \pi } \right) \cdot X\) which constitutes the parameter condition above. Finally, the production quantity under case S(I), \(Q_{\rm S(I)}^{\rm PEN}\), is formulated as follows

Case S(II)

Assuming that \(w + \pi > \left( {c + \pi } \right)/\theta\) holds, case S(II) \((Q \ge X)\) has to be evaluated. The profit generated by the supplier is according to (43)

and can be expressed as

Taking the first-order derivative yields

with \({{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial L\left( {X,Q} \right)} {\partial Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial Q}}\) from (17). Hence, from \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{S}^{\rm PEN} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{S}^{\rm PEN} \left( {Q\left| X \right.} \right)} {{\text{d}}Q}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}Q}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0\) the optimal production input under case S(II), \(Q_{\rm S(II)}^{\rm PEN}\), satisfies the following equation

Hence, the supplier’s production policy under a PEN contract is the following

Note that for \(\pi = 0\) the optimal decision is identical to that under a WHP contract.

The supplier’s profit is concave as the second-order derivative is negative:

Since \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) in (48) is a constant like for the WHP contract, the first-order derivative \({{{\rm d}Q^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}Q^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\) is identical to that in (20).

4.3.2 Buyer decision

The buyer under a PEN contract is compensated for missing units by the penalty rate. The profit the buyer generates is the following

The two cases B(I) \((X \le D)\) and B(II) \((X \ge D)\) are evaluated in the next section.

Case B(I)

The buyer’s profit in case B(I) \((X \le D)\) transforms to

with \(L\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (16). Taking the first-order derivative yields the expression below

with \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (17) and \({{{\text{d}}Q\left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}Q\left( X \right)} {{\text{d}}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}X}}\) from (20). The optimal order quantity under case B(I), \(X_{\rm B(I)}^{\rm PEN}\), then results from \({{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0.\) However, also the case \(X \ge D\) has to be analyzed.

Case B(II)

Under case B(II), i.e., \(X \ge D\), the buyer maximizes the subsequent profit \(\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right) = p \cdot E\left[ {\hbox{min} \left( {D,Y(Q)} \right)} \right] - \left( {w + \pi } \right) \cdot E\left[ {\hbox{min} \left( {X,Y(Q)} \right)} \right] + \pi \cdot X\) that equals

with \(L\left( {D,Q} \right)\) from (5) and \(L\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (16). The buyer’s optimal decision under case B(II), \(X_{\rm B(II)}^{\rm PEN}\), is derived from exploiting the first-order condition \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} {{\text{d}}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}X}}\mathop = \limits^{!} 0\) concerning the derivative below

with \(M\left( {D,Q} \right)\) from (7), \(M\left( {X,Q} \right)\) from (17) and \({{{\rm d}Q\left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}Q\left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}}\) from (20).

4.3.3 Interaction of buyer and supplier

As under the ORS contract, it has to be analyzed whether there exists a combination of contract parameters which guarantees that total supply chain profit is maximized while both, supplier and buyer, accept the contract. To coordinate the supply chain, the optimality conditions of supply chain and supplier under a PEN contract have to be identical. They are given from (8) and (48), respectively:

and

This condition is fulfilled if the buyer orders at demand level, i.e., if \(X^{\rm PEN} = D\) and if \(M\left( {D,Q^{*} } \right) = M\left( {X,Q^{\rm PEN} } \right)\), i.e., if the following condition for the contract parameters is satisfied

which ensures that \({c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c p}} \right. \kern-0pt} p} = {c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c {\left( {w + \pi } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {w + \pi } \right)}}.\) Given the parameter condition, the supplier’s marginal profit in (47) turns out to be zero:

As the supplier’s marginal profit is zero, she actually chooses the corresponding input quantity. Because the buyer anticipates this behavior, it can be evaluated which order decision maximizes his profit. Under case B(II) \((X \ge D)\), the buyer’s marginal profit from (53) in combination with the parameter condition in (54), transforms to

and yields

For proving that \({{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} {{\text{d}}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}X}} < 0\), it will be shown that the penalty \(\pi\) must not be too large. Thus, the determination of the penalty needs particular analysis. Under coordination (given \(p = w + \pi\) and \(X^{\rm PEN} = D\) which leads to \(Q^{\rm PEN} = Q^{*}\)), and using the supply chain profit from (6), the supplier’s and the buyer’s profits from (46) and (52) can be expressed as follows

and

Consequently, for the supplier’s participation constraint to hold, i.e., to generate a non-negative profit, the maximum penalty \(\pi^{ + }\) that results in \(\varPi_{S}^{\rm PEN} \left( {Q^{\rm PEN} \left| {X^{\rm PEN} = D} \right.} \right) = 0\), is given by

From \(\varPi_{\rm SC} \left( {Q^{*} } \right) = p \cdot \left( {1 - F_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right)} \right) \cdot D - \left( {p \cdot \theta \cdot F_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) - c} \right) \cdot Q^{*}\) in (10) we get:

Given the coordinating parameter constellation \(p = w + \pi\), the restriction \(\pi < \pi^{ + }\) transforms to

From that we further get

Under case B(II), from (55), the optimal buyer decision of \(X^{\rm PEN} = D\) is only given if

According to (57) this holds if \(p \cdot \theta \cdot F_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) - c > 0.\)

so that \(p \cdot \theta \cdot F_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) - c = p \cdot \theta \cdot \frac{{\sigma_{Y(Q)}^{*} }}{{2 \cdot \mu_{Y(Q)}^{*} }} \cdot f_{S} \left( {z_{D,Q}^{*} } \right) > 0.\)

Thus, if the participation constraint for the supplier is fulfilled and if the penalty \(\pi\) is restricted to be lower that \(\pi^{ + }\), the buyer’s optimal order quantity will be \(X^{\rm PEN} = D\) in case B(II). Since for \(X \le D\) the first-order derivative in (53) reduces to \({{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\rm d}\varPi_{B}^{\rm PEN} \left( X \right)} {{\rm d}X}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\rm d}X}} = \pi > 0\) the contract coordinating parameter condition \(p = w + \pi\) also initiates \(X^{\rm PEN} = D\) in case B(I). Thus, analogously to the ORS contract, the PEN contract can enable supply chain coordination because the buyer incentivizes the supplier to produce the supply chain optimal amount by ordering at demand level while the contract parameters are fixed appropriately, i.e., under \(p = w + \pi.\)

5 Conclusion and outlook

The analyses in this paper are the first that address the problem of coordination through contracts in supply chains with binomially distributed production yield. They reveal several interesting insights for a buyer–supplier chain with deterministic end-customer demand. The simple WHP contract fails to coordinate, while more sophisticated contracts with reward or penalty scheme enable coordinated behavior in the supply chain without violating the actors’ participation constraints. However, the ORS contract’s ability to coordinate a supply chain depends on the variant that is applied. If a Pull-type contract (without the delivery of excess units) is used, coordination can be achieved. However, if physical delivery of overstock is allowed (Push variant), the contract loses its coordination power. For the PEN contract, however, it can be shown that the design enables SC coordination and, depending on the parameter setting (including a maximum penalty restriction), guarantees an arbitrary profit split.

A comparison with the results from Inderfurth and Clemens (2014) obtained for stochastically proportional yields reveals that all contract designs retain their ability or disability to trigger coordination. For the coordinating contract types, Pull-ORS and PEN, it furthermore turns out that coordination is always coupled with a buyer’s order at demand level. It is also interesting to see that the contract parameter setting which is necessary to coordinate the supply chain under both contract types, i.e., \((w, w_{0})\) in (41) and \((w,\pi)\) in (54), is exactly the same as in the case of stochastically proportional yield. So it becomes evident that the general coordination properties of the studied contracts, including the ability of profit split, do not differ between the different yield types although under binomial yield, different from stochastically proportional yield, the level of the yield uncertainty is critically dependent on the size of the production batch. This property, however, will in first line affect the size of the production and order decision.

Regarding the production quantity, it is found in this paper that demand is inflated to some extent to cope with yield losses. The respective inflation factor, however, is not a constant multiplier of demand like in the case of stochastically proportional yield (see Inderfurth and Clemens 2014). Instead, depending on the cost, price and yield data this inflation factor might increase or decrease with increasing demand level and approaches the reciprocal of the expected yield rate when demand tends to become very large. This is due to the characteristic of binomial yields to monotonically decrease the output risk as the production input level rises up to a level where this risk almost vanishes. The consequences are twofold. First, under comparable parameter settings and identical demand the production level under binomial yield is lower and the expected supply chain profit is higher than in the case of stochastically proportional yield. Second, in high-demand environments the coordination deficit of the simple WHP contract becomes negligible because the yield risk almost disappears in case of binomial yield so that the production decisions in the centralized and decentralized supply chain setting tend to coincide. This is completely different from what is valid under stochastically proportional yield.

The contract analysis for the case of binomial production yield in this paper also permits to study the effects of yield misspecification in the sense that it is assumed that the yield is stochastically proportional, but the real underlying model is binomial. A respective numerical study has been carried out for both settings, the centralized and decentralized one (see " Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is binomial" and "Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is stochastically proportional" in Appendices). In this study the production and order decisions under the wrong yield assumption are inserted in the profit function with correct yield specification with yield parameters that are identical for both yield models. In the centralized case it turns out that a major profit loss of more than 30 % can emerge from such a misspecification, especially if the profitability in terms of price/cost ratio is very small as can be verified in "Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is binomial" in Appendix. In the case of decentralized decision making under a WHP contract, however, the profit loss for the whole supply chain is in general smaller. In some specific cases the supply chain can even profit from yield misspecification since the wrong buyer’s order and supplier’s reaction can improve the total supply chain performance. "Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is stochastically proportional" in Appendix reveals that the same qualitative outcome (with different quantitative results) is found in the case of a reverse misspecification, i.e., if binomial yield is assumed but the real yield is stochastically proportional. The lesson that can be learnt from this specific investigation is that it is very important to specify the yield type correctly. It would be highly interesting to find out if one can distinguish data settings where it really matters to use the true yield model. Such a study, however, is beyond the scope of this paper and will be a matter of future research.

Additionally, further research should focus on extending the supply chain to an emergency option for procuring extra units in case of under-delivery. This option was introduced by Inderfurth and Clemens (2014) and it was shown to coordinate the supply chain by applying the WHP contract. This, however, only holds if the supplier, and not the buyer, is able to utilize the emergency source. In the current setting, this option might reveal a similar performance. Besides, the setting can also be adjusted with respect to supply chain structure. An important aspect in this context is the extension from a serial to a converging supply chain. Another interesting extension of the current work would lie in a contract analysis for an environment where demand is also random. From research in the case of stochastically proportional yield (see Yan and Liu 2009) we know that the simple contracts considered in this paper cannot guarantee coordination while more complex ones might do so. It is an open question, however, if these results also hold under binomially distributed yields.

Concentrating on further types of yield uncertainty, the all-or-nothing type of yield realization, also known as disruption risk (see Xia et al. 2011), has hardly received any attention in literature so far. The same holds for additional yield types mentioned in Yano and Lee (1995), like interrupted geometric yield or yield uncertainty from random capacity. Furthermore, it would be a challenging task to study how contracts can be used for supply chain coordination in planning environments with multiple productions runs that are addressed in Grosfeld-Nir and Gerchak (2004).

Notes

Compare Feller (1968) pp. 174 ff.

The condition which justifies the use of the Normal distribution is the following: \(Q \cdot \theta \cdot \left( {1 - \theta } \right) > 5\) for \(0.1 \le \theta \le 0.9\) (compare Evans et al. 2000 p. 45).

More details of the analyses and all respective proofs can be found in a working paper version of Clemens and Inderfurth (2014) under http://www.fww.ovgu.de/fww_media/femm/femm_2014/2014_11.pdf.

The following analysis is identical to the centralized case with X instead of D and w instead of p.

The result is identical to the second-order derivative of the supply chain profit with X instead of D and w instead of p.

The result is identical to (11) with X instead of D.

References

Asian, Sobhan. 2014. Coordination in supply chains with uncertain demand and disruption risks: existence, analysis, and insights. IEEE Transactions on systems, manufacturing, and cybernetics: systems 44(9): 1139–1154.

Bassok, Yehuda, Wallace J. Hopp, and Manisha Rothagi. 2002. A simple linear heuristic for the service constrained random yield problem. IIE Transactions 34(5): 479–487.

Burnetas, Apostolos, Stephen M. Gilbert, and Craig E. Smith. 2007. Quantity discounts in single-period supply contracts with asymmetric demand information. IIE Transactions 39(5): 465–479.

Clemens, Josephine, Karl Inderfurth. 2014. Supply chain coordination by contracts under binomial production yield, FEMM Working Paper Series, Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaft, 11/2014: Magdeburg.

Corbett, Charles J., and Christopher S. Tang. 1999. Designing supply contracts: Contract type and information asymmetry. In Quantitative Models for Supply Chain Management, ed. Sridhar R. Tayur, Ram Ganeshan, and Michael J. Magazine, 269–297. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Evans, Merran, Nicholas Hastings, and Brian Peacock. 2000. Statistical distributions, 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Feller, William. 1968. An introduction to probability theory and its application: Volume 1, 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York

Gerchak, Yigal, Raymond G. Vickson, and Mahmut Parlar. 1988. Periodic review production models with variable yield and uncertain demand. IIE Transactions 20(2): 144–150.

Grosfeld-Nir, Abraham, and Yigal Gerchak. 2004. Multiple lot sizing in production to order with random yields: review of recent advances. Annals of Operations Research 126: 43–69.

Gurnani, Haresh, Ram Akella, and John Lehoczky. 2000. Supply management in assembly systems with random yield and random demand. IIE Transactions 32(8): 701–714.

Gurnani, Haresh, and Yigal Gerchak. 2007. Coordination in decentralized assembly systems with uncertain component yields. European Journal of Operational Research 176(3): 1559–1576.

He, Yuanjie, and Jiang Zhang. 2008. Random yield risk sharing in a two-level supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics 112(2): 769–781.

Henig, Mordechai, and Yigal Gerchak. 1990. The structure of periodic review policies in the presence of random yield. Operations Research 38(4): 634–643.

Hou, Jing, Amy Z. Zeng, and Lindu Zhao. 2010. Coordination with a backup supplier through buy-back contract under supply disruption. Transportation Research Part E 46(6): 881–895.

Inderfurth, Karl, and Josephine Clemens. 2014. Supply chain coordination by risk sharing contracts under random production yield and deterministic demand. OR Spectrum 36(2): 525–556.

Jones, Philip C., Timothy J. Lowe, Rodney D. Traub, and Greg Kegler. 2001. Matching supply and demand: the value of a second chance in producing hybrid seed corn. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 3(2): 122–137.

Kazaz, Burak. 2004. Production planning under yield and demand uncertainty with yield-dependent cost and price. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 6(3): 209–224.

Maskin, Eric, and Jean Tirole. 1990. The principal-agent relationship with an informed principal: the case of private values. Econometrica 52(2): 379–409.

Nahmias, Steven. 2009. Production and operations analysis, 6th ed. McGraw-Hill: Boston.

Xia, Yusen, Karthik Ramachandran, and Haresh Gurnani. 2011. Sharing demand and supply risk in a supply chain. IIE Transactions 43(6): 451–469.

Yan, Xiaoming, and Ke Liu. 2009. An analysis of pricing power allocation in supply chains of random yield and random demand. International Journal of Information and Management Science 20(3): 415–433.

Yano, Candace Arai, and Hau L. Lee. 1995. Lot sizing with random yields: a review. Operations Research 43(2): 311–334.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Examples for the development of the production/demand ratio

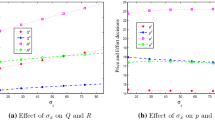

Figure 2 illustrates three exemplary curves for the \(Q/D\)-ratio with increasing demand.

It is evident from the different curves that there is no monotony in the \(Q/D\)-ratio. Yet, the results in (a) and (b) are comparable with typical newsvendor settings where the critical ratio (here it is given by \(c/p\)) determines whether optimal production quantities are below or above expected demand (which corresponds to production yield in our setting). The major difference is that, in addition to prices and costs, also demand has an influence on the production decision as the production risk decreases with increasing quantity. A high margin [as in (a)] causes \(Q/D\) ratios above \(1/\theta\) while low margins [compare (b)] lead to production inputs below the expected yield. Yet, the shape of the curve in (c) is quite interesting. The changes in \(Q/D\) are minor with increasing demand, however, at one point the curve intersects with \(1/\theta\) (which is at \(D = 50\)). For illustrative purpose, the segment \(0 \le D \le 1000\) from curve (c) is extracted in Fig. 3.

Extraction from Fig. 2 part (c)

The intersection with \(1/\theta\) raises the question whether there exist parameter combinations which always guarantee an inflation of demand in the amount of \(1/\theta.\) Figure 4 part (a) answers this question by illustrating the \(c/p\) ratio which results in \(Q/D = 1/\theta\) for increasing demand.

Part (b) of the above figure extracts the range \(0 \le D \le 1000\) from part (a). Comparing this illustration with Fig. 3, the point \(Q/D = 1/\theta\) at \(D = 50\) corresponds to the starting point of the curve in Fig. 4b which is at \({c \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {c p}} \right. \kern-0pt} p} = {1 \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {4.17}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {4.17}} = 0.24.\)

1.2 Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is binomial

For presenting numerical examples we set the parameters as follows: \(c = 1\), \(p = 14\) and \(D = 100.\) The binomially distributed yield is approximated by the normal distribution with mean and standard deviation from (1) and (2). For \(Q \ge D = 100\) this approximation is feasible for \(0.06 \le \theta \le 0.94\) because for these values the condition \(Q \cdot \theta \cdot \left( {1 - \theta } \right) > 5\) is satisfied. In the following Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, miscalculated decision variables and the respective profits are indicated by the superscript mis.

1.3 Effects of yield misspecification if real yield is stochastically proportional

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Clemens, J., Inderfurth, K. Supply chain coordination by contracts under binomial production yield. Bus Res 8, 301–332 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-015-0023-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-015-0023-2