Abstract

Introduction

Inconsistent or superficial access to workplace learning experiences can impede medical students’ development. Well-designed clerkship curricula provide comprehensive education by offering developmental opportunities in and out of the workplace, explicitly linked to competency objectives. Questions remain about how students engage with clerkship curriculum offerings and how this affects their achievement. This study investigated student engagement as the source of an apparent clerkship curriculum malfunction: increasing rate of substandard summative clinical competency exam (SCCX) performance over 3 years following curriculum reform.

Materials and Methods

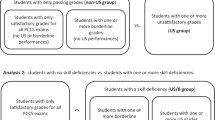

We sampled from three cohorts of US medical students (classes of 2018–2020) based on their post-clerkship SCCX performance: substandard (N = 33) vs. exemplary (N = 31). Using a conceptually based, locally developed rubric, a five-person team rated students’ engagement in a curriculum offering designed to provide standardized deliberate practice on the clerkship’s competency objectives. We examined the association between engagement and SCCX performance, taking prior academic performance into account.

Results

Rate of substandard SCCX performance could not be explained by cohort differences in prior academic performance. Student engagement differed across cohorts and was significantly associated with SCCX performance. However, engagement did not meaningfully predict individual students’ SCCX performance, particularly in light of prior academic performance.

Discussion

Engagement with a particular learning opportunity may not affect clerkship outcomes, but may reflect students’ priorities when navigating curricular offerings, personal learning goals, and curriculum policy. Proposing four patterns of engagement in clerkship learning, this study prompts reflection on the complex interaction among factors that affect engagement and outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Egan T, Jaye C. Communities of clinical practice: the social organization of clinical learning. Health. 2009;13(1):107–25.

Dornan T, Tan N, Boshuizen H, Gick R, Isba R, Mann K, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Timmins E. How and what do medical students learn in clerkships: experience based learning (ExBL). Adv Health Sci Educ. 2014;19:721–49.

Armstrong EG, Mackey M, Spear SJ. Medical education as a process management problem. Acad Med. 2014;79(8):721–8.

Klamen DL. Getting real: embracing the conditions of the third-year clerkship and reimagining the curriculum to enable deliberate practice. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1314–7.

Han H, Roberts NK, Korte R. Learning in the real place. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):231–9.

Williams RG, Klamen DL, White CB, Petrusa E, Fincher RM, Whitfield CF, Shatzer JH, McCarty T, Miller BM. Tracking development of clinical reasoning ability across five medical schools using a progress test. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1148–54.

Han H, Williams R, Hingle S, Klamen DL, Rull GM, Clark T, Daniels J. Medical students’ progress in detecting and interpreting visual and auditory clinical findings. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32(4):380–8.

Williams RG, Klamen DL, Markwell SJ, Cianciolo AT, Colliver JA, Verhulst SJ. Variations in senior medical student diagnostic justification ability. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):790–8.

van Houten-Schat MA, Berkhout JJ, van Dijk N, Endedijk MD, Jaarsma ADC, Diemers AD. Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1008–15.

Dornan T, Hadfield J, Brown M, Boshuizen H, Scherpbier A. How can medical students learn in a self-directed way in the clinical environment? Design-based research Med Educ. 2005;39(4):356–64.

Gofton W, Regehr G. Factors in optimizing the learning environment for surgical training. Clin Ortho Rel Res. 2006;449:100–7.

Fetter M, Robbs R, Cianciolo AT. Clerkship curriculum design and USMLE step 2 performance: exploring the impact of self-regulated exam preparation. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(1):265–76.

Dorsey JK, Beason AM, Verhulst SJ. Relationships matter: enhancing trainee development with a (simple) clerkship curriculum reform. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):76–86.

Klamen DL, Williams R, Hingle S. Getting real: aligning the learning needs of clerkship students with the current clinical environment. Acad Med. 2019;94(1):53–8.

Artino AR Jr, Hemmer PA, Durning SJ. Using self-regulated learning theory to understand the beliefs, emotions, and behaviors of struggling medical students. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):S35-38.

Song HS, Kalet AL, Plass JL. Assessing medical students’ self-regulation as aptitude in computer-based learning. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2011;16(1):97–107.

Cianciolo AT, Klamen DL, Beason AM, Neumeister EL. ASPIRE-ing to excellence at SIUSOM MedEdPublish. 2017. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2017.000082.

Schwartz DL, Bransford JD. A time for telling. Cog Inst. 1998;16(4):475–522.

Williams RG, Klamen DL. Examining the diagnostic justification abilities of fourth-year medical students. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1008–14.

Lievens F, Ones DS, Dilchert S. Personality scale validities increase throughout medical school. J Appl Psych. 2009;94(6):1514–35.

McLachlan JC, Finn G, Macnaughton J. The conscientiousness index: a novel tool to explore students’ professionalism. Acad Med. 2009;84(5):559–65.

Kelly M, O’Flynn S, McLachlan J, Sawdon MA. The clinical conscientiousness index: a valid tool for exploring professionalism in the clinical undergraduate setting. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1218–24.

Foshee CM, Nowacki AS, Shivak JT, Bierer SB. Making much of the mundane: a retrospective examination of undergraduate medical students’ completion of routine tasks and USMLE step 1 performance. Med Sci Educ. 2018;28(2):351–7.

Hojat M, Erdmann JB, Gonnella JS. Personality assessments and outcomes in medical education and the practice of medicine: AMEE Guide No. 79. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):e1267–1301.

Sobowale K, Ham SA, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Personality traits are associated with academic achievement in medical school: a nationally representative study. Acad Psych. 2018;42(3):338–45.

Doherty EM, Nugent E. Personality factors and medical training: a review of the literature. Med Educ. 2011;45(2):132–40.

Cleary TJ, Durning SJ, Artino AR. Microanalytic assessment of self-regulated learning during clinical reasoning tasks: recent developments and next steps. Acad Med. 2016;91(11):1516–21.

Artino AR Jr, Cleary TJ, Dong T, Hemmer PA, Durning SJ. Exploring clinical reasoning in novices: a self-regulated learning microanalytic assessment approach. Med Educ. 2014;48(3):280–91.

Lajoie SP, Zheng J, Li S. Examining the role of self-regulation and emotion in clinical reasoning: implications for developing expertise. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):842–4.

Kroska EB, Calarge C, O’Hara MW, Deumic E, Dindo L. Burnout and depression in medical students: relations with avoidance and disengagement. J Cont Beh Sci. 2017;6(4):404–8.

Walling A, Istas K, Bonaminio GA, Paolo AM, Fontes JD, Davis N, Berardo BA. Medical student perspectives of active learning: a focus group study. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(2):173–80.

Carmody JB, Green LM, Kiger PG, et al. Medical student attitudes toward USMLE step 1 and health systems science—multi-institutional survey. Teach Learn Med. 2020;33(2):139–53.

Feeley AM, Biggerstaff DL. Exam success at undergraduate and graduate-entry medical schools: is learning style or learning approach more important? A critical review exploring links between academic success, learning styles, and learning approaches among school-leaver entry (“traditional”) and graduate-entry (“nontraditional”) medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):237–44.

Steele CM, Aronson J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J Pers Soc Psych. 1995;69(5):797–811.

Cianciolo A, Lower T. Implementing a student-centred year 4 curriculum: initial findings. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1107–8.

Bullock JL, Lockspeiser T, del Pino-Jones A, Richards R, Teherani A, Hauer KE. They don’t see a lot of people my color: a mixed methods study of racial/ethnic stereotype threat among medical students on core clerkships. Acad Med. 2020;95(11S):S58-66.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank members of the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Year 3 Performance Assessment and Evaluation Committee, especially Dr. Debra L. Klamen and Dr. Martha Hlafka, for their consultation on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was deemed exempt from oversight by the Springfield Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (reference #023994).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

CCC Engagement Coding Rubric

-

1.

Case Completion Pattern – 1 metric per student

-

a.

0 = Case completion dates reflect a pattern of cramming cases (i.e., 3+ cases in one day)

-

b.

1 = Case completion dates reflect occasional cramming of cases (i.e., cramming of cases only once)

-

c.

2 = Case completion dates reflect a pattern of spacing cases (i.e., no more than 2 cases per day)

-

a.

-

2.

Optional Self-Assessment DDX Comparison

-

a.

This is the place where students compare the number of DXs on their list to the number on the experts’ list; if the student did not do the comparison, there will be two columns with 0 s.

-

b.

0 = Student did not do any of the optional DDX comparisons

-

c.

1 = Student did some of the optional DDX comparisons

-

d.

2 = Student did all of the optional DDX comparisons

-

a.

-

3.

Optional Thought Questions

-

a.

These are the thought questions that proceed each presentation of new patient information.

-

b.

0 = Student did not do any of the optional thought questions (all questions blank) or typed gibberish (malfeasance)

-

c.

1 = Student did some of the optional thought questions and/or copied/pasted the same text into all thought questions

-

d.

2 = Student wrote generic answers to the optional thought questions that anticipated the next phase of the patient case, but were not specific to the case

-

e.

3 = Student wrote answers to the optional thought questions that not only anticipated the next phase, but were tailored to the specifics of the case

-

a.

-

4.

DXJ – Long Case

-

a.

This is the diagnostic justification that the student presumably updates as the long case evolves. Rating of this item requires looking at how the DXJ evolved with new patient information.

-

b.

0 = DXJ entry reflects active disengagement/malfeasance (e.g., gibberish)

-

c.

1 = DXJ is present, but weakly formulated and/or does not meaningfully change over the course of the case

-

d.

2 = DXJ evolves over the case, but in reflexive, generic fashion (passive management of ideas)

-

e.

3 = DXJ evolves over the case in a way reflects thought, tailoring to the case (active management of ideas)

-

a.

-

5.

DXJ – Mini-cases

-

a.

This is the diagnostic justification that the student presumably bases on the case information provided and updates with each new mini-case. Rating of this item requires looking across mini-cases.

-

b.

0 = DXJ entry reflects active disengagement/malfeasance (e.g., gibberish)

-

c.

1 = DXJ is present, but does not demonstrate a thought process (e.g., single-word answers, circular reasoning, for example: “presenting symptoms”)

-

d.

2 = DXJ evolves over mini-cases, but in reflexive fashion, focused on positive data supporting a single diagnosis

-

e.

3 = DXJ evolves over mini-cases in a way reflects thought, including pertinent positives and negatives

-

a.

-

6.

Self-Assessment Reflection – Final DX for Mini-Cases

-

a.

This is the place where students reflect on why (if applicable) their final DX was different from the experts’.

-

b.

NOTE – There is one self-assessment reflection rating for EACH mini-case.

-

c.

0 = No written reflection (cell is blank)

-

i.

NOTE – If NA appears in the left cell, where agreement with the experts (yes/no) should be specified, this item should be scored a zero. That NA means that the item was not attempted.

-

ii.

NOTE – Do NOT score reflections offered when the diagnosis agreed with the experts.

-

i.

-

d.

1 = Weak reflection (i.e., generic, lacking specifics about where the thought process went wrong, defensiveness, blaming the case/CCC system)

-

e.

2 = Thoughtful reflection (i.e., specific thoughts on how the thought process went awry)

-

f.

NA = Student’s final DX matched the experts’

-

a.

-

7.

Case Completion Date – automatically scored

-

a.

0 = Case was completed w/in 3 days of a deadline (January 1 and March 1)

-

b.

1 = Case was completed 4–10 days before a deadline (January 1 and March 1)

-

c.

2 = Case was completed 10 + days before a deadline (January 1 and March 1)

-

a.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cianciolo, A.T., Ashburn, C., Han, H. et al. If You Build It, Will They Come? Exploring the Impact of Medical Student Engagement on Clerkship Curriculum Outcomes. Med.Sci.Educ. 33, 205–214 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01739-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-023-01739-6