Abstract

Introduction

We applied Azjen’s theory of planned behavior (TPB) and Triandis’ theory of interpersonal behavior (TIB) to understand medical students’ intention to change behavior based on feedback received during an obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. Both models presume that behavioral intention is strongly related to actual behavior.

Materials and Methods

We collected free-text responses from students during a year-long Feedback Focused initiative on the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship at Harvard Medical School. Students reported feedback daily and what they would change based on that feedback. We applied TPB and TIB to identify students’ motivation to change. We analyzed data using directed content analysis.

Results

We reviewed 1,443 feedback entries from 122 students between July 2, 2018, and May 31, 2019. Self-efficacy was the most commonly represented component, related to a student expressing their own role, ability, or skill integrating the feedback (85%). Some entries (11%) focused on students’ attitudes or beliefs about the outcome of the implemented feedback, usually patient focused but sometimes about the learner’s outcome. Intentions motivated by social norms and expectations focused on the perceived or stated expectations of others, usually a superior or a team (11%). A small number of entries (1.7%) indicated that students had an emotional response to challenging or meaningful feedback.

Conclusions

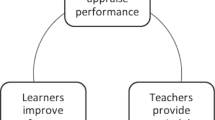

While self-efficacy is an important change motivator, faculty development geared toward improving the provision of meaningful feedback that bridges a desired behavior change to an outcome of interest, framed through the attitudes and beliefs or social norms lens, may improve trainee performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Van de Ridder JM, Stokking KM, McGaghie WC, ten Cate OTJ. What is feedback in clinical education? Med Educ. 2008;42:189–97.

Ramani S, Konings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med Teach. 2018;41(6):625–31.

Sklar DP, McMahon GT. Trust between teachers and learners. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2157–8.

Bing-You R, Varaklis K, Hayes V. The feedback tango: an integrative review and analysis of the content of the teacher-learner feedback exchange. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):657–63.

William T, Branch MD Jr, Anuradha P. Feedback and reflection: teaching methods for clinical settings. Acad Med. 2002;77(12):1185–8.

Al-Mously N, Nabil NM, Al-Babtain SA. Undergraduate medical students’ perceptions on the quality of feedback received during clinical rotations. Med Teach. 2014;36:S23.

Gil DH, Heins M, Jones P. Perceptions of medical school faculty members and students on clinical clerkship feedback. J Med Educ. 1984;59:856–64.

Bing-You RG, Trowbridge RL. Why medical educators may be failing at feedback. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1330–1.

Fromme HB, Mariani AH, Zegarek MH, Swearingen S, Schumann S, Ryan MS, et al. Utilizing feedback: helping learners make sense of the feedback they get. MedEdPORTAL. 2015;11:10159.

Strudwick G, Booth R, Mistry K. Can social cognitive theories help us understand nurses’ use of electronic health records? Comput Inform Nurs. 2016;34(4):169–74.

Thompson-Leduc P, Clayman ML, Turcotte S, Légaré F. Shared decision-making behaviours in health professionals: a systematic review of studies based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):754–74.

Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals’ intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci. 2008;16(3):36.

Perkins MB, Jensen PS, Jaccard J, Gollwitzer P, Oettingen G, Pappadopulos E, et al. Applying theory-driven approaches to understanding and modifying clinicians’ behavior: what do we know? Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):342–8.

Medlock S, Wyatt JC. Health behaviour theory in health informatics: support for positive change. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2019;30(263):146–58.

de Feijter JM, de Grave WS, Hopmans EM, Koopmans RP, Scherpbier AJ. Reflective learning in a patient safety course for final-year medical students. Med Teach. 2012;34(11):946–54.

Abamecha F, Godesso A, Girma E. Predicting intention to use voluntary HIV counseling and testing services among health professionals in Jimma, Ethiopia, using the theory of planned behavior. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;14(6):399–407.

Kam LY, Knott VE, Wilson C, Chambers SK. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand health professionals’ attitudes and intentions to refer cancer patients for psychosocial support. Psycho-oncol. 2012;21(3):316–23.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1113–27.

Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckman, ed(s). Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. p. 11–39.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Triandis HC. Values, attitudes and interpersonal behavior. In Volume 27. Lincoln NE, ed(s). Nebraska Symposium on Motivation Beliefs, Attitudes and Values. University of Nebraska Press; 1980. p. 195–259.

Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, Katsufrakis PJ, Leslie KM, Patel VL, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):460–7.

Johnson NR, Pelletier A, Royce C, Goldfarb I, Singh T, Lau TC, et al. Feedback Focused: a learner- and teacher-centered curriculum to improve the feedback exchange in the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11127.

Bergman E, de Feijter J, Frambach J, Godefrooij M, et al. AM last page: a guide to research paradigms relevant to medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):545.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Waugh SM, He J. Inter-rater agreement estimates for data with high prevalence of a single response. J Nurs Meas. 2019;27(2):152–61.

Jha V, Brockbank S, Roberts T. A framework for understanding lapses in professionalism among medical students: applying the theory of planned behavior to fitness to practice cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1622–7.

Archer R, Elder W, Hustedde C, Milam A, Joyce J. The theory of planned behaviour in medical education: a model for integrating professionalism training. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):771–7.

Myran DT, Carew CL, Tang J, Whyte H, Fisher WA. Medical students’ intentions to seek abortion training and to provide abortion services in future practice. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(3):236–44.

Wald HS, Anthony D, Hutchinson TA, Liben S, Smilovitch M, Donato AA. Professional identity formation in medical education for humanistic, resilient physicians: pedagogic strategies for bridging theory to practice. Acad Med. 2015;90:753–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Harvard Medical School Program in Medical Education (PME) Educational Scholarship Review Committee. The study was determined a quality improvement initiative, requiring no additional review. Informed consent was not required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, N.R., Dzara, K., Pelletier, A. et al. Medical Students’ Intention to Change After Receiving Formative Feedback: Employing Social Cognitive Theories of Behavior. Med.Sci.Educ. 32, 1447–1454 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01668-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-022-01668-w