Abstract

Background

Physician trainees are not provided with routine practice opportunities to have a serious illness conversation, which includes a discussion of patient expectations, concerns, and preferences regarding an advancing illness.

Objective

To test the acceptability of incorporating a serious illness conversation into routine trainee practice.

Methods

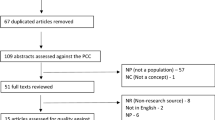

Residents in an internal medicine program conducted a serious illness conversation in the ambulatory care setting with the assistance of a conversation guide. Semi-structured interviews determined trainees’ perceptions of the educational intervention. Patients were surveyed to understand their experience.

Results

Twenty-one trainees had at least one opportunity to practice having a serious illness conversation and completed a majority of the conversation elements. In semi-structured interviews, trainees expressed the belief that the serious illness conversation should be an important component of routine patient care, understood that patients are willing to have these conversations, discovered that patients did not have a clear understanding of their prognosis, and said that time is the main barrier to having these conversations more consistently. Patients found the conversation to be important (92%), reassuring (83%), and of higher quality than the communication of a usual doctor visit (83%).

Conclusions

With preparation, time, and a conversation guide, trainees completed the elements of a serious illness conversation and found it to be an important addition to their routine practice. Patients found the conversation to be important, reassuring, and of better quality than their usual visits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lakin JR, Koritsanszky LA, Cunningham R, Maloney FL, Neal BJ, Paladino J, et al. A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care. Health Aff. 2017;36(7):1258–64.

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340(mar23 1):c1345–5.

Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, Perkins AJ, Zhou XH, Wolinsky FD. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients’ satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Jan;16(1):32–40.

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2008 Oct 8;300(14):1665–73.

Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013 Feb;61(2):209–14.

Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Mar 9;169(5):480–8.

Institute of Medicine. Dying in America improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life the pressing need to improve end-of-life care. Institute of Medicine. 2014.

Pope TM. ason. Legal Briefing: Medicare coverage of advance care planning. J Clin Ethics. 2015;26(4):361–7.

Poppe M, Burleigh S, Banerjee S. Qualitative evaluation of advanced care planning in early dementia (ACP-ED). PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60412.

Emanuel LL, Barry MJ, Stoeckle JD, Ettelson LM, Emanuel EJ. Advance directives for medical care — a case for greater use. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(13):889–95.

Malcomson H, Bisbee S. Perspectives of healthy elders on advance care planning. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(1):18–23.

Tung EE, North F. Advance care planning in the primary care setting: a comparison of attending staff and resident barriers. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2009;26(6):456–63.

Glaudemans JJ, Van Charante EPM, Willems DL. Advance care planning in primary care, only for severely ill patients? A structured review. Fam Pract. 2015;32(1):16–26.

Snyder S, Hazelett S, Allen K, Radwany S. Physician Knowledge, Attitude, and experience with advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: results of a primary care survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2013;30(5):419–24.

Abarshi E, Echteld M, Donker G, Van den Block L, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Deliens L. Discussing end-of-life issues in the last months of life: a nationwide study among general practitioners. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(3):323–30.

De Vleminck A, Houttekier D, Pardon K, Deschepper R, Van Audenhove C, Vander Stichele R, et al. Barriers and facilitators for general practitioners to engage in advance care planning: a systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2013 Dec;31(4):215–26.

Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, Walder S, Butow PN, Carrick S, Currow D, Ghersi D, Glare P, Hagerty R, Tattersall MH. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Vol. 21, Palliative Medicine. Sage PublicationsSage UK: London, England; 2007. p. 507–17.

Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, Smucker WD. Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Vol. 45, Gerontologist. Oxford University Press; 2005. p. 107–17.

Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):445–51.

Lakin JR, Block SD, Andrew Billings J, Koritsanszky LA, Cunningham R, Wichmann L, et al. Improving communication about serious illness in primary care a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1380–7.

Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff. 2010;29:1310–8.

Tulsky JA. Interventions to enhance communication among patients, providers, and families. J Palliat Med. 2005;8 Suppl 1(supplement 1):S95–102.

Sulmasy DP, Song KY, Marx ES, Mitchell JM. Strategies to promote the use of advance directives in a residency outpatient practice. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11(11):657–63.

Chan D, Ward E, Lapin B, Marschke M, Thomas M, Lund A, et al. Outpatient advance care planning internal medicine resident curriculum: valuing our patients’ wishes. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(7):734–45.

Berns SH, Camargo M, Meier DE, Yuen JK. Goals of Care Ambulatory resident education: training residents in advance care planning conversations in the outpatient setting. J Palliat Med. 2017;jpm.2016.0273.

Dreyfus SE. The five-stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 2004 Jun 24;24(3):177–81.

Smith CS, Irby DM. The roles of experience and reflection in ambulatory care education. Acad Med. 1997;72(1):32–5.

Schmidt HG, Norman GR, Boshuizen HP. A cognitive perspective on medical expertise. Acad Med. 1990;65(10):611–21.

Bekelman DB, Johnson-Koenke R, Ahluwalia SC, Walling AM, Peterson J, Sudore RL. Development and feasibility of a structured goals of care communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2017;jpm.2016.0383.

Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, Smith G, Paladino J, Lipsitz S, Gawande AA, Block SD. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10).

Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E. Identifying the population with serious illness: the “denominator” challenge. J Palliat Med. 2017;21(S2):jpm.2017.0548.

Association of American Medical Colleges. ACGME Residents and fellows who are International Medical Graduates (IMGs) by Specialty, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Conflicts of interests were disclosed.

Human and animal rights and Informed consent

This was an educational research involving human subjects. Informed consent was always attained.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pottash, M., Joseph, L. & Rhodes, G. Practicing Serious Illness Conversations in Graduate Medical Education. Med.Sci.Educ. 30, 1187–1193 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00991-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00991-4