Abstract

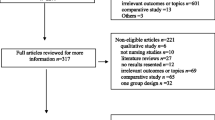

Many simulation courses now exist which aim to prepare first-year doctors for the task of assessing and managing potentially deteriorating patients. Despite the substantial resources required, the degree to which participants benefit from such courses, and which aspects of the simulation training are optimal for learning, remains unclear. A systematic literature search was undertaken across seven electronic databases. Inclusion criteria were that the intervention must be a simulation of a deteriorating patient scenario that would likely be experienced by first-year doctors, and that participants being first-year doctors or in their final year of medical school. Studies reporting quantitative benefits of simulation on participants’ knowledge and simulator performance underwent meta-analyses. The search returned 1444 articles, of which 48 met inclusion criteria. All studies showed a benefit of simulation training, but outcomes were largely limited to self-rated or objective tests of knowledge, or simulator performance. The meta-analysis demonstrated that simulation improved participant performance by 16% as assessed by structured observation of a simulated scenario, and participant knowledge by 7% as assessed by written assessments. A mixed-methods analysis found conflicting evidence about which aspects of simulation were optimal for learning. The results of the review indicate that simulation is an important tool to improve first-year doctors’ confidence, knowledge and simulator performance with regard to assessment and management of a potentially deteriorating patient. Future research should now seek to clarify the extent to which these improvements translate into clinical practice, and which aspects of simulation are best suited to achieve this.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Brennan N, Corrigan O, Allard J, Archer J, Barnes R, Bleakley A, et al. The transition from medical student to junior doctor: today’s experiences of Tomorrow’s Doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):449–58.

Cameron A, Millar J, Szmidt N, Hanlon K, Cleland J. Can new doctors be prepared for practice? A review. Clin Teach. 2014;11(3):188–92.

Cave J, Woolf K, Jones A, Dacre J. Easing the transition from student to doctor: how can medical schools help prepare their graduates for starting work? Med Teach. 2009;31(5):403–8.

Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. The first house officer year: views of graduate and non-graduate entrants to medical school. Med Educ. 2008;42(3):286–93.

Cave J, Goldacre M, Lambert T, Woolf K, Jones A, Dacre J. Newly qualified doctors’ views about whether their medical school had trained them well: questionnaire surveys. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7(1):38.

Tallentire V, Smith S, Wylde K, Cameron H. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of Foundation training? Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1031):590–5.

Matheson C, Matheson D. How well prepared are medical students for their first year as doctors? The views of consultants and specialist registrars in two teaching hospitals. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(1009):582–9.

Wijnen-Meijer M, ten Cate O, van der Schaaf M, Harendza S. Graduates from vertically integrated curricula. Clin Teach. 2013;10(3):155–9.

Carling J. Are graduate doctors adequately prepared to manage acutely unwell patients? Clin Teach. 2010;7(2):102–5.

Lempp H, Cochrane M, Rees J. A qualitative study of the perceptions and experiences of pre-registration house officers on teamwork and support. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):10.

Jen MH, Bottle A, Majeed A, Bell D, Aylin P. Early in-hospital mortality following trainee doctors’ first day at work. PLoS One. 2009;4(9):e7103.

Young JQ, Ranji SR, Wachter RM, Lee CM, Niehaus B, Auerbach AD. “July effect”: impact of the academic year-end changeover on patient outcomes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):309–15.

Tallentire V, Smith S, Skinner J, Cameron H. The preparedness of UK graduates in acute care: a systematic literature review. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88(1041):365–71.

Smith G, Poplett N. Knowledge of aspects of acute care in trainee doctors. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(920):335–8.

Burford B, Whittle V, Vance GH. The relationship between medical student learning opportunities and preparedness for practice: a questionnaire study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):223.

Bull S, Mattick K, Postlethwaite K. ‘Junior doctor decision making: isn’t that an oxymoron?’ A qualitative analysis of junior doctors’ ward-based decision-making. J Vocation Educ Train. 2013;65(3):402–21.

Forrest K, McKimm J, Edgar S. Essential simulation in clinical education. John Wiley & Sons; 2013.

Stalmeijer RE, Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, Scherpbier AJ. Cognitive apprenticeship in clinical practice: can it stimulate learning in the opinion of students? Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):535–46.

Sheehan D, Wilkinson TJ, Billett S. Interns’ participation and learning in clinical environments in a New Zealand hospital. Acad Med. 2005;80(3):302–8.

Kolb AY. The Kolb learning style inventory-version 3.1 2005 technical specifications, vol. 200. Boston: Hay Resource Direct; 2005. p. 72.

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–e72.

Seabrook MA. Clinical students’ initial reports of the educational climate in a single medical school. Med Educ. 2004;38(6):659–69.

Torre DM, Simpson D, Sebastian JL, Elnicki DM. Learning/feedback activities and high-quality teaching: perceptions of third-year medical students during an inpatient rotation. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):950–4.

Hammick M, Dornan T, Steinert Y. Conducting a best evidence systematic review. Part 1: from idea to data coding. BEME Guide No. 13. Med Teach. 2010;32(1):3–15.

Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. Evaluating training programs. San Francisco: Barrett. Koehler Publishing, Inc; 1998.

Okuda Y, Bryson EO, DeMaria S, Jacobson L, Quinones J, Shen B, et al. The utility of simulation in medical education: what is the evidence? Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76(4):330–43.

Cleland J, Patey R, Thomas I, Walker K, O’Connor P, Russ S. Supporting transitions in medical career pathways: the role of simulation-based education. Adv Simul. 2016;1(1):14.

Thistlethwaite J. Interprofessional education: a review of context, learning and the research agenda. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):58–70.

Singh P, Aggarwal R, Pucher PH, Darzi A. Development, organisation and implementation of a surgical skills ‘boot camp’: SIMweek. World J Surg. 2015;39(7):1649–60.

Blackmore C, Austin J, Lopushinsky SR, Donnon T. Effects of postgraduate medical education “boot camps” on clinical skills, knowledge, and confidence: a meta-analysis. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):643–52.

Schmidt E, Goldhaber-Fiebert SN, Ho LA, McDonald KM. Simulation exercises as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5_Part_2):426–32.

Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Bordage G. Quality of reporting of experimental studies in medical education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):737–45.

Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. In: McNally R, editor. Handbook of research on teaching. Washington: American Educational Research Association; 1963.

HQSCNZ. Patient deterioration. Health Quality and Safety Commission, New Zealand. 2018. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/patient-deterioration/. Accessed 28th October 2018.

Smith ME, Navaratnam A, Jablenska L, Dimitriadis PA, Sharma R. A randomized controlled trial of simulation-based training for ear, nose, and throat emergencies. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(8):1816–21.

Swords C, Smith M, Wasson J, Qayyum A, Tysome J. Validation of a new ENT emergencies course for first-on-call doctors. J Laryngol Otol. 2017;131(2):106–12.

New Zealand Curriculum Framework for Prevocational Medical Training. Medical Council of New Zealand. 2014. https://www.mcnz.org.nz/assets/News-and-Publications/NZCF26Feb2014.pdf. Accessed 14/09/16 2016.

Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3.: Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014.

Jensen L, Merry A, Webster C, Weller J, Larsson L. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2004;59(5):493–504.

Webster CS, Luo AY, Krägeloh C, Moir F, Henning M. A systematic review of the health benefits of Tai Chi for students in higher education. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:103–12.

Norman G, Eva KW. Quantitative research methods in medical education. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice. 2nd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2014. p. 301–22.

Boet S, Sharma S, Goldman J, Reeves S. Medical education research: an overview of methods. Can J Anesth. 2012;59(2):159–70.

Turner TL, Balmer DF, Coverdale JH. Methodologies and study designs relevant to medical education research. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013;25(3):301–10.

Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2011. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Montreal: McGill University; 2011.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Ten Eyck RP, Tews M, Ballester JM. Improved medical student satisfaction and test performance with a simulation-based emergency medicine curriculum: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(5):684–91.

Semler MW, Keriwala RD, Clune JK, Rice TW, Pugh ME, Wheeler AP, et al. A randomized trial comparing didactics, demonstration, and simulation for teaching teamwork to medical residents. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(4):512–9.

Steadman RH, Coates WC, Huang YM, Matevosian R, Larmon BR, McCullough L, et al. Simulation-based training is superior to problem-based learning for the acquisition of critical assessment and management skills. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(1):151–7.

Thomas I. Student views of stressful simulated ward rounds. Clin Teach. 2015;12(5):346–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12329.

Ruesseler M, Weinlich M, Müller MP, Byhahn C, Marzi I, Walcher F. Simulation training improves ability to manage medical emergencies. Emerg Med J. 2010;27(10):734–8.

Smith G, Poplett N. Impact of attending a 1-day multi-professional course (ALERT™) on the knowledge of acute care in trainee doctors. Resuscitation. 2004;61(2):117–22.

Timmis C, Speirs K. Student perspectives on post-simulation debriefing. Clin Teach. 2015;12(6):418–22.

Mathai SK, Miloslavsky EM, Contreras-Valdes FM, Milosh-Zinkus T, Hayden EM, Gordon JA, et al. How we implemented a resident-led medical simulation curriculum in a large internal medicine residency program. Med Teach. 2014;36(4):279–83. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.875619.

McGlynn MC, Scott HR, Thomson C, Peacock S, Paton C. How we equip undergraduates with prioritisation skills using simulated teaching scenarios. Med Teach. 2012;34(7):526–9.

Shekhter I, Nevo I, Fitzpatrick M, Everett-Thomas R, Sanko JS, Birnbach DJ. Creating a common patient safety denominator: the interns’ course. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):269–72.

Miloslavsky EM, Hayden EM, Currier PF, Mathai SK, Contreras-Valdes F, Gordon JA. Pilot program using medical simulation in clinical decision-making training for internal medicine interns. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):490–5. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-11-00261.1.

Lumley S. An hour on call: simulation for medical students. Med Educ. 2013;47(11):1125.

Minha S, Shefet D, Sagi D, Berkenstadt H, Ziv A. “See one, sim one, do one”—a national pre-internship boot-camp to ensure a safer “student to doctor” transition. PLoS One. 2016;11(3).

Esterl RM, Henzi DL, Cohn SM. Senior medical student “boot camp”: can result in increased self-confidence before starting surgery internships. Curr Surg. 2006;63(4):264–8.

Mollo EA, Reinke CE, Nelson C, Holena DN, Kann B, Williams N, et al. The simulated ward: ideal for training clinical clerks in an era of patient safety. J Surg Res. 2012;177(1):e1–6.

Watmough S, Box H, Bennett N, Stewart A, Farrell M. Unexpected medical undergraduate simulation training (UMUST): can unexpected medical simulation scenarios help prepare medical students for the transition to foundation year doctor? BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):110.

Meier AH, Henry J, Marine R, Murray WB. Implementation of a Web- and simulation-based curriculum to ease the transition from medical school to surgical internship. Am J Surg. 2005;190(1):137–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.04.007.

Arora S, Hull L, Fitzpatrick M, Sevdalis N, Birnbach DJ. Crisis management on surgical wards: a simulation-based approach to enhancing technical, teamwork, and patient interaction skills. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):888–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000824.

Saunsbury E, Allison E. Promoting the management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeds among junior doctors: a quality improvement project. BMJ Open Quality. 2015;4(1):u206305–w3502.

Weller J, Robinson B, Larsen P, Caldwell C. Simulation-based training to improve acute care skills in medical undergraduates. N Z Med J. 2004;117(1204):42–9.

Vestal HS, Sowden G, Nejad S, Stoklosa J, Valcourt SC, Keary C, et al. Simulation-based training for residents in the management of acute agitation: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(1):62–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0559-2.

Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Moazed F, Caprio T, Didwania A, McGaghie WC, et al. Making July safer: simulation-based mastery learning during intern boot cAMP. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):233–9.

Wayne DB, Cohen ER, Singer BD, Moazed F, Barsuk JH, Lyons EA, et al. Progress toward improving medical school graduates’ skills via a “boot camp” curriculum. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(1):33–9.

Frischknecht AC, Boehler ML, Schwind CJ, Brunsvold ME, Gruppen LD, Brenner MJ, et al. How prepared are your interns to take calls? Results of a multi-institutional study of simulated pages to prepare medical students for surgery internship. Am J Surg. 2014;208(2):307–15.

Rogers GD, McConnell HW, De Rooy NJ, Ellem F, Lombard M. A randomised controlled trial of extended immersion in multi-method continuing simulation to prepare senior medical students for practice as junior doctors. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-90.

Rialon KL, Barfield ME, Elfenbein DM, Lunsford KE, Tracy ET, Migaly J. Resident designed intern orientation to address the new ACGME common program requirements for resident supervision. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(3):350–6.

Antonoff MB, Shelstad RC, Schmitz C, Chipman J, D’Cunha J. A novel critical skills curriculum for surgical interns incorporating simulation training improves readiness for acute inpatient care. J Surg Educ. 2009;66(5):248–54.

Fernandez GL, Lee PC, Page DW, D’Amour EM, Wait RB, Seymour NE. Implementation of full patient simulation training in surgical residency. J Surg Educ. 2010;67(6):393–9.

Nguyen HB, Daniel-Underwood L, Van Ginkel C, Wong M, Lee D, San Lucas A, et al. An educational course including medical simulation for early goal-directed therapy and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: an evaluation for medical student training. Resuscitation. 2009;80(6):674–9.

Pantelidis P, Staikoglou N, Paparoidamis G, Drosos C, Karamaroudis S, Samara A, et al. Medical students’ satisfaction with the applied basic clinical seminar with scenarios for students, a novel simulation-based learning method in Greece. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2016;13.

Schroedl CJ, Corbridge TC, Cohen ER, Fakhran SS, Schimmel D, McGaghie WC, et al. Use of simulation-based education to improve resident learning and patient care in the medical intensive care unit: a randomized trial. J Crit Care. 2012;27(2):e213–9.

Krajewski A, Filippa D, Staff I, Singh R, Kirton OC. Implementation of an intern boot camp curriculum to address clinical competencies under the new Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education supervision requirements and duty hour restrictions. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(8):727–32.

Ker JS, Hesketh EA, Anderson F, Johnston DA. Can a ward simulation exercise achieve the realism that reflects the complexity of everyday practice junior doctors encounter? Med Teach. 2006;28(4):330–4.

Dow A, Mahata M, Call S. A simulation-based orientation curriculum to teach residency program values and prepare interns for day one. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:193.

Laack TA, Newman JS, Goyal DG, Torsher LC. A 1-week simulated internship course helps prepare medical students for transition to residency. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(3):127–32.

Stroben F, Schröder T, Dannenberg KA, Thomas A, Exadaktylos A, Hautz WE. A simulated night shift in the emergency room increases students’ self-efficacy independent of role taking over during simulation. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0699-9.

Green CA, Vaughn CJ, Wyles SM, O’Sullivan PS, Kim EH, Chern H. Evaluation of a surgery-based adjunct course for senior medical students entering surgical residencies. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(4):631–8.

Powell N, Bruce CG, Redfern O. Teaching a ‘good’ ward round. Clin Med. 2015;15(2):135–8. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.15-2-135.

Parekh A, Thorpe T. How should we teach undergraduates in simulation scenarios? Clin Teach. 2012;9(5):280–4.

Ford H, Cleland J, Thomas I. Simulated ward round: reducing costs, not outcomes. Clin Teach. 2016.

Weller J, Henderson R, Webster CS, Shulruf B, Torrie J, Davies E, et al. Building the evidence on simulation validity: comparison of anesthesiologists’ communication patterns in real and simulated cases. Anaesthesiology. 2014;120(1):142–8.

Norcini JJ. The mini clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX). Clin Teach. 2005;2(1):25–30.

Mitchell I, McKay H, Van Leuvan C, Berry R, McCutcheon C, Avard B, et al. A prospective controlled trial of the effect of a multi-faceted intervention on early recognition and intervention in deteriorating hospital patients. Resuscitation. 2010;81(6):658–66.

Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JPA. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1148–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyn065.

Higgins JPT. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1158–60.

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/471-2288-8-79.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.186.

Bhatnagar D, Mohiuddin AG, Lazarus C. Night float 101: entrustment of professional activities. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:S835–S6.

Miyasaka KW, Buchholz JM, Martin ND, La Marra D, Williams NN, Morris JB, et al. The successful development and implementation of a novel, acute care surgical simulation pathway training curriculum. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2014;28:330.

McGregor CA, Paton C, Thomson C, Chandratilake M, Scott H. Preparing medical students for clinical decision making: a pilot study exploring how students make decisions and the perceived impact of a clinical decision making teaching intervention. Med Teach. 2012;34(7):508–17. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.670323.

Schwind CJ, Boehler ML, Markwell SJ, Williams RG, Brenner MJ. Use of simulated pages to prepare medical students for internship and improve patient safety. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):77–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Buist, N., Webster, C.S. Simulation Training to Improve the Ability of First-Year Doctors to Assess and Manage Deteriorating Patients: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med.Sci.Educ. 29, 749–761 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00755-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00755-9