Abstract

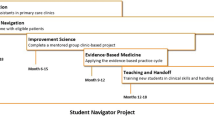

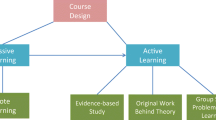

Within the last decade, there has been increasing interest in transforming undergraduate medical education through integrating basic, clinical, and social sciences. The Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine, which graduated its first class in 2015, brought together a group of medical educators to develop a fully integrated curriculum. Here, we describe the “First 100 Weeks” of our curriculum and address the means by which we integrate at the program, course, session, and assessment level. We view integration as a strategy to train physicians to contextualize basic science through application to clinical medicine; to determine if this goal is met requires a novel approach to assessment. In our curriculum, students progress through a series of single courses. Each week’s theme is anchored to our problem-based/cased-based learning program, Patient-Centered Explorations in Active Reasoning, Learning and Synthesis (PEARLS), which raises learning issues in biomedical, clinical, and social sciences. All large- and small-group sessions are thoughtfully constructed and positioned to enhance learning from PEARLS without pre-empting or duplicating it. All sessions belong to one of three course components: Mechanisms of Health, Disease, and Intervention; Structure, an integrated anatomy, histology, pathology, imaging and physical diagnosis laboratory; and Patient-Physician and Society, comprised of weekly clinical experiences and skills development, and examination of societal drivers of healthcare. Students complete formative and summative case-based assessments. We describe the details of our curricular and assessment strategies as well as important lessons learned along the way. These include the value of aligning philosophy, organizational structure, integrated content, and assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Irby DM et al. Calls for reform of medical education by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: 1910 and 2010. Acad Med. 2010;85:220–7.

Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. In: Swansick T, editor. Understanding medical education: evidence, theory and practice. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 7–30.

Ambrose SA, Bridges M, DiPietro M et al. How learning works: seven research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass; 2010.

Woods NN et al. It all makes sense: biomedical knowledge, causal connections and memory in the novice diagnostician. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2007;12:405–15.

Kulasegaram KM et al. Cognition before curriculum: rethinking the integration of basic science and clinical learning. Acad Med. 2013;88:1–8.

Goldman E, Schroth WS. Deconstructing integration: a framework for the rational application of integration as a guiding curricular strategy. Acad Med. 2012;87:729–34.

Martimianakis MA et al. Understanding the challenges of integrating scientists and clinical teachers in psychiatry education: Findings from an innovative faculty development program. Acad Psych. 2009;33:241–7.

Brauer DG, Ferguson KJ. The integrated curriculum in medical education. Med Teach. 2015;37:312–22.

Kwiatkowski T et al. Medical students as EMTs: skill building, confidence and professional formation. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:24829.

Harden RM. Curriculum mapping: a tool for transparent and authentic teaching and learning. Med Teach. 2001;23:123–37.

Bandiera G et al. Integration and timing of basic and clinical sciences education. Med Teach. 2013;35:381–7.

Jones R et al. Changing face of medical curricula. Lancet. 2001;357:699–703.

Muller JH et al. Lessons learned about integrating a medical school curriculum: perceptions of students, faculty and curriculum leaders. Med Educ. 2008;42:778–85.

Stevenson F et al. Paired basic science and clinical problem-based learning faculty teaching side by side: do students evaluate them differently? Med Educ. 2005;39:194–201.

Epstein RM. Assessment in Medical Education. New Eng J Med. 2007;356:387–96.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the administrators, faculty, staff, and students at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine who made the work described here possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ginzburg, S., Brenner, J. & Willey, J. Integration: a Strategy for Turning Knowledge into Action. Med.Sci.Educ. 25, 533–543 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0174-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-015-0174-y