Abstract

Background

Omalizumab is recommended as adjunctive therapy for antihistamine-refractory chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). However, its long-term effectiveness is understudied. The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) have shown prognostic value in cancer, strokes, and other diseases.

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of omalizumab in CSU patients while investigating potential associations of SII and SIRI with the drug survival of omalizumab.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted using patient data from the electronic hospital database, including patients with CSU treated with omalizumab between January 2018 and May 2021. Drug survival curves were visualized using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. and Cox regression was utilized to assess potential associations.

Results

A total of 109 CSU treated with omalizumab at the University Hospital of Zurich were included. The mean drug survival was 13.6 ± 10.9 months. The mean SII and SIRI were 796.1 ± 961.3 and 2.1 ± 3.1, respectively. The multivariate model revealed that SIRI (p = 0.098) was a more robust predictor of omalizumab’s drug survival than SII (p = 0.367), while concurrent autoimmune disease or baseline immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels showed no significant impact.

Conclusion

This study suggests the potential utility of SIRI as a superior predictive indicator for omalizumab’s drug survival in CSU patients compared to SII. Concomitant autoimmune disease or baseline IgE levels did not significantly affect the drug’s effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

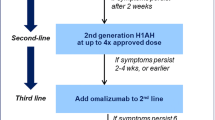

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a mast-cell driven disease characterized by the presence of recurring hives and wheals and/or angioedema lasting a minimum of six weeks [1]. It affects approximately 0.5 to 1% of the global population [2,3,4]. Current guidelines recommend that second-generation H1-antihistamines be used as first-line treatment for CSU, with escalation up to four times the approved dose as second-line treatment if symptoms persist [1, 5]. Refractory cases of CSU should then receive adjunctive therapy with omalizumab (Xolair®), a monoclonal antibody directed against Immunoglobulin E (IgE) [6], which has demonstrated high efficacy and safety for the treatment of chronic urticaria (CU) [6,7,8,9,10,11].

Drug survival refers to the length of time a patient receives a particular medication until discontinuation due to any reason. This parameter not only allows for the assessment of long-term impact, safety and effectiveness, but also of several influencing factors, such as tolerability and patient and doctor preferences [12, 13]. In previous studies, average omalizumab drug survival was described to be 443.1 days (= 14.6 months) in patients with CSU [14]. However, several predictors of omalizumab response and drug survival have been described in recent years. Chronic inducible urticaria (CindU) was found to be an independent predictor of overall longer drug survival in CU patients [15], whereas other studies found pre-treatment IgE levels to robustly predict response to omalizumab [16, 17].

The systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) and the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) have been linked to the overall prognosis of variety of diseases like cancer, stroke or pneumonia [18,19,20]. It has been postulated that these indices could potentially also act as predictive markers for drug survival in CSU [21].

The aim of this study was to evaluate omalizumab drug survival in a large daily practice cohort from Switzerland and to assess predictive values of SII and SIRI indices on this survival rate.

Methods

Patient characteristics and data acquisition

Following ethical approval (BASEC-Nr.: 2021-01715), the electronic medical database at the University Hospital Zurich’s Department of Dermatology was searched for adult patients (≥ 18 years) with CSU treated with omalizumab between January 2018 and May 2021. The primary database search yielded a total of 181 cases. The following inclusion criteria were then applied: patients must be at least 18 years old, have a definitive diagnosis of CSU made by a board-certified allergologist or dermatologist, be treated with oral antihistamines for at least 4 weeks, have treatment with omalizumab 300 mg per month, have a documented outcome of either good response or no response, and have written general consent. Any patients not meeting inclusion criteria, who classified as partial responders and/or without accepted general consent were excluded from this study, as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

The following parameters were then extracted from the electronic medical database: age, sex, pre-existing illnesses including history of atopy, clinical characteristics, presence of angioedema, presence of chronic inducible urticaria (CindU), disease duration before treatment initiation, prior therapy, pre-treatment blood values (IgE, tryptase, complete blood count), omalizumab injection dates, concurrent immunosuppressive treatments and medication, clinical response at data lock, timing of first clinical improvement, treatment termination date, reason for discontinuation and side effects.

Calculation of SII and SIRI

SII and SIRI were calculated using the complete blood count as follows [22]:

SII = platelet count [G/L] × neutrophil count [G/L]/lymphocyte count [G/L].

SIRI = monocyte count [G/L] × neutrophil count [G/L]/lymphocyte count [G/L].

Procedures

Based on recent CSU guidelines, participants who remained symptomatic after 4 weeks of antihistamine therapy with four times the approved dose were eligible for treatment with 300 mg subcutaneous omalizumab every 4 weeks [1, 23]. Blood samples were drawn prior to the first administration to establish baseline IgE levels. First patient follow-ups and efficacy assessments took place three months after treatment initiation. Clinical responses were rated into three categories based on to the patients’ reported outcomes as well as their dermatologists’ judgments: good, partial and no response. Good responders were defined as patients whose symptoms completely vanished during omalizumab treatment. Partial responders demonstrated slight improvement only and, hence, experienced recurrence of wheals either less frequently or less intensively under administration of omalizumab. Patients who demonstrated insufficient clinical improvement were considered for higher omalizumab doses as per recent literature [24,25,26]. This led to exclusion, as previous studies demonstrated the dose-effect-relationship to influence response [9]. In accordance with current guidelines, treatment was regularly interrupted every five to six months to assess whether urticaria persisted [1, 27]. During these interruptions, the spontaneous course of the disease was evaluated, and treatment was only restarted if patients experienced recurrence of urticaria symptoms. Post-withdrawal relapse led to a deduction of injection free months from total treatment time and re-administration of the last effective dose [28]. If treatment was discontinued, either due to resolution of symptoms or a change in therapeutic strategy, the last injection date was recorded as termination date. Partial responders were excluded, resulting in a clear responder and a non-responder group. Drug survival was defined as treatment duration, with an event being defined as the definitive discontinuation of omalizumab. This study was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.2.2) with p-values ≤ 0.05 indicating significance. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to visualize drug survival. Initial screening of associations with drug survival was performed via univariate Cox regression analysis. The proportional hazard assumption was verified by examining individual Schoenfeld residuals. Previous studies used p-values ≤ 0.2 for inclusion in the multivariate Cox regression model [15]. Due to only IgE passing this screening, the minimum p-value was raised to ≤ 0.3, allowing both IgE and sex to be included in the multivariate Cox regression curves. Three multivariate models with baseline variables alone, baseline variables and SII, and with baseline variables and SIRI were evaluated. The 66 (60.6%) patients who were still on continuous treatment with omalizumab at data lock were not excluded due to group size.

The Cox regression model describes the hazard function as a function of time and covariates to assess event risk (e.g. the discontinuation of omalizumab) at a given time, assuming survival (e.g. regular omalizumab administration) up to that point. The hazard ratio, represented by Exp(coeff), represents omalizumab discontinuation risk change per unit increase in the covariate, with all other model covariates held constant.

Results

Sample size

From January 2018 to May 2021, 181 patients were assessed for eligibility. A total of 109 patients were enrolled in this study, as they were ≥ 18 years old as of index date, had a definitive diagnosis of CSU made by a board-certified allergologist or dermatologist, had ≥ 4 weeks of treatment with oral antihistamines, were treated with 300 mg omalizumab per 4 weeks, were not partial responders, and had given written general consent.

Demographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, the overall population, consisting of 63 (57.8%) female and 46 (42.2%) male patients showed a mean (± SD) age of 40.6 ± 14.7 years. All patients had hives and wheals, whereas 46 (42.2%) patients had concomitant angioedema. 41 (37.6%) patients were identified as having an inducible component, classified as CSU with an inducible component (CSU-CindU). Ten (9.1%) patients demonstrated concomitant autoimmune disease, defined as the presence of any autoimmune disease such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis at the beginning of omalizumab therapy. Atopy, which was defined as a clinical history of allergic rhinitis, asthma, or atopic dermatitis, was positive in 39 (35.7%) patients. The medical records of 4 (3.7%) patients did not contain a conclusive start of symptoms date. The remaining 105 (96.3%) patients showed an average disease duration prior to initiation of omalizumab treatment of 49.2 ± 74.7 months.

Immunomodulatory medication was administered to 33 (30.3%) patients, either as an adjunctive to omalizumab treatment, or for pre-existing concomitant autoimmune disease. Prednisone was administered to 30 (27.5%) patients, of which 9 (30.0%) on a continuous basis and 21 (70.0%) on an as-needed basis, 2 (1.8%) patients received cyclosporine and 3 (2.8%) with others (1 nivaquine, 1 plaquenil, 1 azathioprine). All the patients included in this study were co-medicated with oral antihistamines during their omalizumab treatment. Additionally, 10 (9.2%) patients were treated with montelukast. One patient was treated with colchicine and dapsone.

Laboratory evaluations

As depicted in Table 2, 90 (82.56%) patients underwent a differential blood count before initiating omalizumab treatment, showing an average SII of 796.1 ± 961.3 and average SIRI of 2.1 ± 3.1. The average plasma levels for various blood components were as follows: neutrophils (5.2 ± 2.4 G/L), lymphocytes (2.3 ± 1.1 G/L), monocytes (0.8 ± 1.4 G/L), eosinophils (0.2 ± 0.1 G/L) and basophils (0.03 ± 0.02 G/L). Regarding specific IgE measurements, pre-treatment data was available for 69 (63.3%) patients, with an average baseline IgE level of 205 ± 250.2 IU/mL. Non-responders demonstrated an average baseline IgE level of 103.3 ± 118.5 IU/mL. Additionally, 73 (70.0%) patients were tested for tryptase, showing an average baseline value of 5.4 ± 3.3 ug/L.

Response at data lock

Table 3 shows the clinical responses of all patients at data lock. Of the 109 patients included in this study, 95 (87.2%) responded positively to treatment, while 14 (12.8%) were classified as non-responders. Among the 95 responders, 53 (55.8%) demonstrated an early response (prior to the second administration) and 35 (36.8%) showed a delayed response (between the second and fourth administration). The exact timing of improvement was not documented for the remaining 7 (7.3%) responders.

Drug survival

Amongst all 109 patients included in this study, mean treatment duration was 25.7 ± 19.6 months at time of data lock. Of the 43 (39.4%) patients who had discontinued omalizumab treatment, average treatment duration was 13.6 ± 10.9 months, as seen in Fig. 2. More than half of these patients discontinued treatment due to remission, as seen in Table 4.

Table 5 presents the univariate model representing sex, age, concomitant autoimmune disease, baseline IgE, tryptase, SII and SIRI’s effects on omalizumab drug survival of omalizumab. None of the variables had significant Schoenfeld residuals, confirming survival testing assumptions. Three variables (sex [p-value = 0.281], concomitant autoimmune disease [p-value = 0.106] and baseline serum IgE [p-value = 0.195]) showed p-values < 0.3, warranting inclusion in a primary multivariate Cox regression model to assess for drug survival. However, concomitant autoimmune disease did not correlate with drug survival in the multivariate model (p-value = 0.915). After exclusion of concomitant autoimmune disease, SII and SIRI demonstrated a p-value of 0.367 and 0.098 respectively in the multivariate model including sex and baseline IgE, as demonstrated in Table 6. The correlation between SIRI and the drug survival of omalizumab is shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion

Among 109 patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) enrolled in this retrospective single center study, 43 (39.4%) patients discontinued omalizumab treatment after a mean treatment duration of 13.6 ± 10.9 months, which is comparable to the findings of previous studies, two of which postulated a mean drug survival between 13.3 and 14.6 months, respectively [14, 29]. However, both studies considered temporary pauses as an event in determining drug survival. A third study described a drug survival of 8.5 months only [30].

Accumulating evidence supports the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) to be a precise predictor of outcome in tumors and other diseases [18, 31, 32]. Similar to SII, the systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) also emerged as an independent prognostic factor for comparable diseases. [20, 33, 34]. SII and SIRI, identified as reliable inflammatory markers, could be associated to CSU and may predict omalizumab drug survival. In our study, average SII and SIRI were 796.1 ± 961.3 and 2.1 ± 3.1 respectively, which is slightly higher than 552 (137–2270) and 1.4 ± 0.7 reported by Coşansu [21].

In this study, the univariate analysis did not demonstrate significant p-values for neither SII (p-value = 0.635) nor SIRI (p-value = 0.763), suggesting that neither factor in isolation had a strong correlation with omalizumab drug survival. While not reaching statistical significance, the multivariate analysis revealed pre-treatment SIRI (p-value = 0.098) as a more reliable omalizumab drug survival predictor than pre-treatment SII (p-value = 0.393). This suggests that SIRI might have some bearing on omalizumab drug survival and that a high baseline SIRI could improve omalizumab drug survival. These results are consistent with previous studies such as Coşansu et al., who established a correlation between both SIRI and SII with omalizumab response at three months in CSU [21]. However, further investigation is needed to establish their potential predictive value.

Current literature suggests a reduction of mast cell releasability and basopenia reversion under omalizumab therapy [35, 36]. This result is supported by current literature, which underlines the important role of mast-cell activation in the pathogenesis of chronic spontaneous urticaria [37]. Although the significance of basophil levels in CSU has already been documented in previous studies [38,39,40], basophil levels are included similarly in the calculation of SII and SIRI and can therefore not explain the difference in prognostic factor of omalizumab drug survival.

CSU is considered a risk factor for autoimmune diseases [41], with prevalence up to 28% in patients with CSU [42]. However, only 10 (9.1%) patients in this study had concomitant autoimmune disease. The multivariate analysis failed to demonstrate a significant effect of concomitant autoimmune disease on omalizumab drug survival (p-value = 0.915). This is an important finding which reflects results of a recent study, showing that thyroid autoimmunity, formerly considered a potential marker of type IIb CSU, is unable to predict omalizumab response [43].

In spite of prior research indicating better and faster response to omalizumab treatment in patients with elevated baseline serum IgE, this study found limited prognostic value for omalizumab drug survival from baseline IgE levels (p-values of 0.367 and 0.5421 in multivariate analysis with SII and SIRI, respectively) [16, 17, 44]. However, mean baseline IgE levels were higher than other studies, suggesting that the majority of the cohort presented with type I CSU, a condition associated with a prompt response to omalizumab [45]. Consistent with prior research, poor responders demonstrated an average baseline IgE level of 103.3 ± 118.5 IU/mL only [35, 45, 46].

Therefore, baseline IgE, is a predictor of omalizumab response, but might not always be a reliable indicator of duration of the disease and, hence, of omalizumab drug survival. Individual omalizumab dosing was adjusted in accordance with clinical results, as described in recent literature [24,25,26]—patients with little to no clinical improvement qualified for higher omalizumab doses, typically 600 mg every 4 weeks or 300 mg every 2 weeks. This led to exclusion in our study due to the demonstrated dose-effect-relationship influencing response [9].

This study provides valuable insights into omalizumabs’ effectiveness in treating CSU. One significant strength is the centralized patient care at the University Hospital Zurich, at one of the largest university hospitals in Switzerland, enabling standardized diagnosis, management, treatment, improved patient follow-up, minimized confounders, and comprehensive data collection. A limitation, however, is that no validated numerical instrument such as the Urticaria Activity Score [47] was used to measure symptom reduction more accurately with omalizumab treatment. Lastly, co-medication usage might have influenced the clinical response and therefore the drug survival of omalizumab.

In conclusion, this study found limited predictive value for omalizumab drug survival from concomitant autoimmune disease. The systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) proved to be a more reliable predictor than the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII). However, neither of both indices reached statistical significance and can therefore be promoted as a useful predictive tool. Nevertheless, these findings contribute to ongoing efforts to optimize omalizumab treatment for CSU.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [PSG].

Abbreviations

- CindU:

-

Chronic inducible urticaria

- CSU:

-

Chronic spontaneous urticaria

- CSU:

-

Chronic spontaneous urticaria

- CU:

-

Chronic urticaria

- IgE:

-

Immunoglobulin E

- SII:

-

Systemic immune-inflammation index

- SIRI:

-

Systemic inflammatory response index

References

Zuberbier T, Latiff AAH, Abuzakouk M, Aquilina S, Asero R, Baker D, et al. The international EAACI/GA2LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2022;77:734–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15090.

Saini SS. Chronic spontaneous urticaria: etiology and pathogenesis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014;34:33–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iac.2013.09.012.

Fricke J, Ávila G, Keller T, Weller K, Lau S, Maurer M, et al. Prevalence of chronic urticaria in children and adults across the globe: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Allergy. 2020;75:423–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14037.

Maurer M, Weller K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Giménez-Arnau A, Bousquet PJ, Bousquet J, et al. Unmet clinical needs in chronic spontaneous urticaria. A GA2LEN task force report. Allergy. 2011;66:317–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02496.x.

Iriarte Sotés P, Armisén M, Usero-Bárcena T, Fernández AR, Rivas MMO, Gonzalez MT, et al. Efficacy and safety of up-dosing antihistamines in chronic spontaneous urticaria: a systematic review of the literature. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2021;31:282–91. https://doi.org/10.18176/jiaci.0649.

Maurer M, Altrichter S, Bieber T, Biedermann T, Bräutigam M, Seyfried S, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic urticaria who exhibit IgE against thyroperoxidase. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:202–209.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.038.

Okayama Y, Matsumoto H, Odajima H, Takahagi S, Hide M, Okubo K. Roles of omalizumab in various allergic diseases. Allergol Int. 2020;69:167–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alit.2020.01.004.

Hon KL, Leung AKC, Ng WGG, Loo SK. Chronic urticaria: an overview of treatment and recent patents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019;13:27–37. https://doi.org/10.2174/1872213X13666190328164931.

Saini S, Rosen KE, Hsieh HJ, Wong DA, Conner E, Kaplan A, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study of single-dose omalizumab in patients with H1-antihistamine-refractory chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:567–573.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.010.

Metz M, Vadasz Z, Kocatürk E, Giménez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab updosing in chronic spontaneous urticaria: an overview of real-world evidence. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;59:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08794-6.

Saini SS, Bindslev-Jensen C, Maurer M, Grob JJ, Baskan BE, Bradley MS, et al. Efficacy and safety of omalizumab in patients with chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria who remain symptomatic on H1 antihistamines: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:67–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.306.

van den Reek JMPA, Kievit W, Gniadecki R, Goeman JJ, Zweegers J, van de Kerkhof PCM, et al. Drug survival studies in dermatology: principles, purposes, and pitfalls. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2015.171.

Lin PT, Wang SH, Chi CC. Drug survival of biologics in treating psoriasis: a meta-analysis of real-world evidence. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16068. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-34293-y.

Ke X, Kavati A, Wertz D, Huang Q, Wang L, Willey VJ, et al. Real-world characteristics and treatment patterns in patients with urticaria initiating omalizumab in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24:598–606. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.7.598.

Spekhorst LS, van den Reek JMPA, Knulst AC, Röckmann H. Determinants of omalizumab drug survival in a long-term daily practice cohort of patients with chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2019;74:1185–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13714.

Fok JS, Kolkhir P, Church MK, Maurer M. Predictors of treatment response in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2021;76:2965–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14757.

Altrichter S, Fok JS, Jiao Q, Kolkhir P, Pyatilova P, Romero SM, et al. Total IgE as a marker for chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13:206–18. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2021.13.2.206.

Ma M, Yu N, Wu B. High systemic immune-inflammation index represents an unfavorable prognosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3973–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S201269.

Chen Y, Lin YX, Pang Y, Zhang JH, Gu JJ, Zhang GQ, et al. Systemic inflammatory response index improves the prediction of postoperative pneumonia following meningioma resection. chin Med J. 2020;134:728–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000001298.

Zhang Y, Xing Z, Zhou K, Jiang S. The predictive role of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in the prognosis of stroke patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1997–2007. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S339221.

Coşansu NC, Kara R, Yaldiz M, Dikicier BS. New markers to predict the response to omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15589. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15589.

Jin Z, Wu Q, Chen S, Gao J, Li X, Zhang X, et al. The associations of two novel inflammation indexes, SII and SIRI with the risks for cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: a ten-year follow-up study in 85,154 individuals. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:131–40. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S283835.

Hacard F, Giraudeau B, d’Acremont G, Jegou MH, Jonville-Bera AP, Munck S, et al. Guidelines for the management of chronic spontaneous urticaria: recommendations supported by the Centre of Evidence of the French Society of Dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:658–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20415.

Vadasz Z, Tal Y, Rotem M, Shichter-Confino V, Mahlab-Guri K, Graif Y, et al. Omalizumab for severe chronic spontaneous urticaria: real-life experiences of 280 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1743–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.035.

Kocatürk E, Deza G, Kızıltaç K, Giménez-Arnau AM. Omalizumab updosing for better disease control in chronic spontaneous urticaria patients. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2018;177:360–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000491530.

Salman A, Comert E. The real-life effectiveness and safety of omalizumab updosing in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:496–500. https://doi.org/10.1177/1203475419847956.

Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Asero R, Latiff AAH, Baker D, Ballmer-Weber B, et al. The EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria. Allergy. 2018;73:1393–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13397.

Sussman G, Hébert J, Gulliver W, Lynde C, Yang WH, Papp K, et al. Omalizumab re-treatment and step-up in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria: OPTIMA trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2372–2378.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.022.

Ghazanfar MN, Sand C, Thomsen SF. Effectiveness and safety of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous or inducible urticaria: evaluation of 154 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(2):404–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14540.

Apalla Z, Sidiropoulos T, Kampouropoulou E, Papageorgiou M, Lallas A, Lazaridou E, et al. Real-life, long-term data on efficacy, safety, response and discontinuation patterns of omalizumab in a Greek population with chronic spontaneous urticaria. Eur J Dermatol. 2020;30:716–22. https://doi.org/10.1684/ejd.2020.3919.

Li C, Tian W, Zhao F, Li M, Ye Q, Wei Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, SII, for prognosis of elderly patients with newly diagnosed tumors. Oncotarget. 2018;9:35293–9. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24293.

Hou D, Wang C, Luo Y, Ye X, Han X, Feng Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) but not platelet-albumin-bilirubin (PALBI) grade is associated with severity of acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Int J Neurosci. 2021;131:1203–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207454.2020.1784166.

Geng Y, Zhu D, Wu C, Wu J, Wang Q, Li R, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting postoperative survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;65:503–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2018.10.002.

Zhou Q, Su S, You W, Wang T, Ren T, Zhu L. Systemic inflammation response index as a prognostic marker in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 cohorts. Dose Response. 2021;19:15593258211064744. https://doi.org/10.1177/15593258211064744.

Kaplan AP, Giménez-Arnau AM, Saini SS. Mechanisms of action that contribute to efficacy of omalizumab in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy. 2017;72:519–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13083.

Carter MC, Robyn JA, Bressler PB, Walker JC, Shapiro GG, Metcalfe DD. Omalizumab for the treatment of unprovoked anaphylaxis in patients with systemic mastocytosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1550–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.032.

Chang TW, Chen C, Lin CJ, Metz M, Church MK, Maurer M. The potential pharmacologic mechanisms of omalizumab in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:337–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.036.

MacGlashan D, Saini S, Schroeder JT. Response of peripheral blood basophils in subjects with chronic spontaneous urticaria during treatment with omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:2295–2304.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.039.

Johal KJ, Chichester KL, Oliver ET, Devine KC, Bieneman AP, Schroeder JT, et al. The efficacy of omalizumab treatment in chronic spontaneous urticaria is associated with basophil phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:2271–2280.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.02.038.

Gericke J, Ohanyan T, Church MK, Maurer M, Metz M. Omalizumab may not inhibit mast cell and basophil activation in vitro. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1832–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12693.

Kolkhir P, Borzova E, Grattan C, Asero R, Pogorelov D, Maurer M. Autoimmune comorbidity in chronic spontaneous urticaria: A systematic review. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:1196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.003.

Kolkhir P, Altrichter S, Asero R, Daschner A, Ferrer M, Giménez-Arnau A, et al. Autoimmune diseases are linked to type IIb autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13:545–59. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2021.13.4.545.

Asero R, Ferrucci SM, Calzari P, Consonni D, Cugno M. Thyroid autoimmunity in CSU: a potential marker of omalizumab response? Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:7491. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087491.

Gericke J, Metz M, Ohanyan T, Weller K, Altrichter S, Skov PS, et al. Serum autoreactivity predicts time to response to omalizumab therapy in chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1059–1061.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.047.

Ertas R, Ozyurt K, Ozlu E, Yilmaz U, Avci A, Atasoy M, et al. Increased IgE levels are linked to faster relapse in patients with omalizumab-discontinued chronic spontaneous urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1749–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.007.

Jeong SH, Lim DJ, Chang SE, Kim KH, Kim KJ, Park EJ. Omalizumab on chronic spontaneous urticaria and chronic inducible urticaria: a real-world study of efficacy and predictors of treatment outcome. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e211. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e211.

Hawro T, Ohanyan T, Schoepke N, Metz M, Peveling-Oberhag A, Staubach P, et al. The Urticaria Activity Score-Validity, Reliability, and Responsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1185–1190.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.10.001.

Funding

CG received a research grant from University of Zurich, Faculty of Medicine (Filling the Gap) to perform research at the Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AF: Conception and design, acquisition/analysis, and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, final approval, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CG: Conception and design, acquisition/analysis, and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, final approval, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SM: Conception and design, acquisition/analysis, and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, final approval, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. CL: Conception and design, acquisition/analysis, and interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, final approval, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. PSG: Conception and design, data interpretation, critical revision for important intellectual content, final approval, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

P. Schmid-Grendelmeier has received honoraria for advisory boards and speaker fees from Novartis. A. Fabi, S. Milosavljevic, C.C.V. Lang and C. Guillet declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants or on human tissue were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1975 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was approved by the institute’s committee on human research (Kantonale Ethik-Kommission Zürich, BASEC Nr.: 2021-01715). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors C. Guillet and P.S. Schmid-Grendelmeier contributed equally to the manuscript.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in the final manuscript in order to improve readability of the paper. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabi, A., Milosavljevic, S., Lang, C.C.V. et al. Predictive value of the systemic immune inflammation index and systemic inflammatory response index on omalizumab drug survival in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Allergo J Int 33, 32–40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-023-00278-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-023-00278-1