Abstract

Introduction

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) often caused by alternative complement dysregulation. Patients with aHUS can present with malignant hypertension (MHT), which may also cause TMA.

Methods

This analysis of the Global aHUS Registry (NCT01522183) assessed demographics and clinical characteristics in eculizumab-treated and not-treated patients with aHUS, with (n = 71) and without (n = 1026) malignant hypertension, to further elucidate the potential relationship between aHUS and malignant hypertension.

Results

While demographics were similar, patients with aHUS + malignant hypertension had an increased need for renal replacement therapy, including kidney transplantation (47% vs 32%), and more pathogenic variants/anti-complement factor H antibodies (56% vs 37%) than those without malignant hypertension. Not-treated patients with malignant hypertension had the highest incidence of variants/antibodies (65%) and a greater need for kidney transplantation than treated patients with malignant hypertension (65% vs none). In a multivariate analysis, the risk of end-stage kidney disease or death was similar between not-treated patients irrespective of malignant hypertension and was significantly reduced in treated vs not-treated patients with aHUS + malignant hypertension (adjusted HR (95% CI), 0.11 [0.01–0.87], P = 0.036).

Conclusions

These results confirm the high severity and poor prognosis of untreated aHUS and suggest that eculizumab is effective in patients with aHUS ± malignant hypertension. Furthermore, these data highlight the importance of accurate, timely diagnosis and treatment in these populations and support consideration of aHUS in patients with malignant hypertension and TMA.

Trial registration details

Atypical Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome (aHUS) Registry.

Registry number: NCT01522183 (first listed 31st January, 2012; start date 30th April, 2012).

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) typically caused by alternative complement pathway dysregulation, that is often classified as a complement-mediated TMA (CM-TMA) [1,2,3,4]. aHUS is characterized by thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and acute kidney injury and can also present as progressive kidney damage, or as extrarenal manifestations resulting in damage to other organs [5,6,7]. Another condition that can result in TMA is malignant hypertension (MHT), a severe form of arterial hypertension traditionally diagnosed by high blood pressure (diastolic pressure > 120 mmHg) with papilledema/hypertensive retinopathy [8,9,10,11,12]. More recent experience has emphasized the role of multi-organ involvement/damage in the diagnosis and prognosis of MHT, and MHT with multi-organ involvement has also been referred to as hypertensive emergency [10, 13]. The kidneys are frequently affected in patients with MHT, and patients often present with elevated serum creatinine, proteinuria, hemolysis, low platelet count, and kidney failure, all of which are also key markers of TMA [10, 14]. Further, complement dysregulation has also been implicated in patients with hypertension-associated TMA, with one study finding that 87.5% of patient serum samples induced formation of abnormal C5b-9 on microvascular endothelial cells in vitro. This has previously been proposed as a highly specific assessment of complement dysregulation/activation in patients with aHUS [15].

Previous studies have suggested that aHUS and MHT are common comorbid conditions, although their precise relationship has often been unclear [16,17,18,19]. Recent evidence suggests that while MHT is highly prevalent in patients with aHUS, among all cases of MHT, aHUS remains a marginal cause. There is also evidence of direct associations between MHT and development of TMA [8, 9, 13, 20]. The interplay/overlap between these conditions means that establishing causality is often extremely difficult. Despite the difficulties associated with differentiating between MHT and aHUS, establishing a clear and correct diagnosis is extremely important as the underlying mechanisms and treatment choices differ significantly. The current standard of care in patients diagnosed with aHUS is complement C5 inhibitor therapy, while patients presenting with MHT will typically be treated with blood pressure lowering medications [21, 22]. Due to the substantially different pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these conditions, delays in diagnosis and sub-optimal treatment regimens can have considerable, negative effects on patient outcomes. Finally, it is presently unknown whether the complement C5 inhibitor eculizumab is effective in treating patients with aHUS and MHT.

Using data from the Global aHUS Registry, the largest registry of real-world data relating to patients with aHUS, this analysis characterized pediatric and adult patients with aHUS, both with and without MHT, who were either treated or not treated with eculizumab. This study explored the baseline characteristics of these patient groups and assessed the risk of reaching the composite endpoint of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) or death. Clinical characteristics and outcomes are also presented by adult and pediatric designation.

Methods

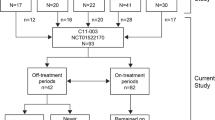

This retrospective analysis utilized data from the Global aHUS Registry (NCT01522183), an observational, non-interventional, multicenter registry that retrospectively and prospectively collects demographic information, natural history data, and treatment outcomes of patients with aHUS. The registry methodology and initial patient characteristics have previously been reported [23]. This analysis included patients enrolled into the registry from April 2012 until 26 October, 2020 [23]. Patients were included if they were enrolled in the registry and were followed up for ≥ 90 days after initial aHUS presentation or diagnosis date. aHUS was diagnosed locally, with no central registry definition of aHUS used. Patients in the MHT cohort were also required to have a recorded diagnosis of MHT, as defined by the local registry investigator/treating physician, and applied criteria usually included diastolic blood pressure > 120 mmHg, alongside papilledema, retinopathy and/or exudates. No definition of severe hypertension was available within the registry. Patients were excluded from this analysis if they withdrew consent from the registry or discontinued eculizumab due to a revised diagnosis of any condition other than aHUS. To assess the effects of eculizumab on outcomes, patients were defined as either treated or not-treated. Patients not treated with eculizumab included any patients who were never treated with eculizumab, or who received eculizumab after reaching ESKD (defined as kidney transplantation or chronic maintenance dialysis), or who received eculizumab up to and including one month prior to kidney transplantation. No minimum duration of eculizumab administration was required for inclusion in the treated group. Patient disposition for this analysis is presented in Fig. 1.

Patient disposition. aIncludes all patients enrolled in the Global aHUS Registry from April 2012 to 26 October, 2020; bNot-treated patients included any patients who were never treated with eculizumab; who received eculizumab after reaching ESKD, defined as kidney transplantation or chronic maintenance dialysis; or who received eculizumab up to and including 1 month prior to kidney transplantation. aHUS atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, MHT malignant hypertension

The following variables were extracted for analysis; age at aHUS diagnosis, sex, time to eculizumab initiation, family history of aHUS, timing of MHT diagnosis (related to the time of initial aHUS presentation), new extra-renal manifestations of aHUS not present at initial diagnosis (number and organ system), pathogenic genetic variant status and presence of autoantibodies to complement factor H, triggering conditions other than MHT, kidney transplant status, and baseline serum creatinine, platelet counts and lactate dehydrogenase levels. Baseline was defined as the closest value to aHUS onset in either direction. The primary outcome of interest was the composite endpoint of time to ESKD or death. The variables and primary endpoint were stratified by treatment status, MHT status, and age group (pediatric [< 18 years] vs adult).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized as median (min, max), while categorical data were summarized as number of patients (%). Laboratory parameters were presented using both number of patients with available data (%) and median (min, max) for values. No formal statistical comparisons were performed on baseline characteristics data. Kaplan–Meier survival plots were generated for the composite endpoint, and hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated using Cox regression analysis. Both unadjusted and adjusted HRs and 95% confidence intervals are reported. HRs for the comparison of treated vs not-treated patients with aHUS and MHT were adjusted for plasma exchange/plasma infusion at the time of initial TMA, dialysis at the time of initial TMA, and the presence of any pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies. HRs for the comparison of not-treated patients with aHUS with vs without MHT were adjusted for age at initial onset of aHUS, sex, and the presence of any pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies. For assessment of the composite endpoint, propensity matching by age at initial onset of aHUS, sex, and presence of pathogenic genetic variants was performed. Additionally, only those patients with recorded genetic testing results had their genetic data included in the analysis. Any missing data were excluded from this analysis.

Results

Patient disposition

Patient disposition is presented in Fig. 1. At the time of this analysis, a total of 1903 patients were enrolled in the Global aHUS Registry. Following application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1797 of the 1903 patients were eligible for this study. A further 695 patients were excluded due to unknown MHT status and five due to unknown eculizumab treatment status (1 with MHT, 4 without MHT). This analysis therefore included 1097 patients; 71 presenting with both aHUS and MHT (20 treated and 51 not treated with eculizumab) and 1026 presenting with aHUS without MHT (429 treated and 597 not treated with eculizumab).

Overall, 20 (28%) patients with aHUS and MHT were treated with eculizumab, compared to 429 (42%) patients without MHT. Of the 72 patients with aHUS and MHT, 23 (32%) had a recorded onset of aHUS prior to 2011, while of the 1030 patients with aHUS without MHT, 323 (31%) had a recorded onset of aHUS prior to 2011. Eculizumab was granted marketing authorization in 2011.

Patient demographics

Key patient demographics are presented in Table 1 and patient demographics stratified by age group are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Age at aHUS diagnosis, sex, and family history of aHUS were all similar between patients with aHUS both with and without MHT, irrespective of treatment status. Patients with aHUS and MHT had a slight numerical increase in the percentage of new extra-renal manifestations of aHUS across all organ systems. Genetic screening for at least one pathogenic complement variant was conducted in 61 (86%) patients with aHUS and MHT, and in 742 (72%) patients with aHUS without MHT. Of these, 34 (48%) with aHUS and MHT had their results recorded in the registry, compared to 300 (29%) patients without MHT. Testing for anti-CFH antibodies was performed in 11 (16%) patients with aHUS and MHT and in 91 (9%) patients with aHUS without MHT. Among patients whose genetic screening results were entered in the registry database, those with aHUS and MHT had a higher proportion of pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies compared to aHUS patients without MHT (40 [56%] vs 382 [37%]). Further, patients with aHUS and MHT who were not treated with eculizumab were found to have a much higher proportion of pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies (33 [65%]) than those with aHUS and MHT who were treated with eculizumab (7 [35%]), or those with aHUS without MHT regardless of treatment status (treated, 152 [35%], not-treated, 230 [39%]).

A greater proportion of patients with aHUS and MHT received a kidney transplant compared to patients without MHT (33 [47%] vs 324 [32%]). However, the proportion of patients with aHUS requiring a kidney transplant was higher in those not treated than in those treated with eculizumab, regardless of whether they had comorbid MHT or not (with MHT, 33 [65%] vs 0 [0%]; without MHT, 304 [51%] vs 20 [5%]). Of the 33 not-treated patients with aHUS and MHT who required a kidney transplant, two had a transplant at the time of aHUS diagnosis, two prior to a diagnosis of aHUS, and two had no date of transplantation recorded in the registry; all other patients had a transplant after receiving a diagnosis of aHUS.

Aside from patients with aHUS and MHT treated with eculizumab—who reported no triggering conditions other than MHT—similar, small proportions of patients reported triggering conditions other than MHT in all other patient cohorts (Table 1).

Time to ESKD or death

Kaplan–Meier plots and HRs for the combined endpoint of ESKD or death are presented in Fig. 2, and full HR analyses are available in Supplementary Table S2. Figure 2a presents a comparison of treated and not treated patients with aHUS and MHT. Treated patients had a significantly reduced risk of reaching ESKD or death compared to not-treated patients (unadjusted HR [95% CI], 0.04 [0.01–0.30], P = 0.002; adjusted HR [95% CI], 0.11 [0.01–0.87], P = 0.036). Figure 2b presents a comparison of patients with aHUS both with and without MHT who were not treated with eculizumab. Not-treated patients with aHUS and MHT were not at a significantly increased risk of ESKD or death compared to not-treated patients without MHT (unadjusted HR [95% CI], 1.18 [0.82–1.68], P = 0.373; adjusted HR [95% CI], 1.15 [0.80–1.64], P = 0.451).

Kaplan–Meier plots for time to ESKD or death from initial onset of aHUS for a patients with aHUS and MHT who were treated vs patients with aHUS and MHT who were not-treated; b untreated patients with aHUS and MHT vs untreated patients with aHUS without MHTa. a71 subjects with ESKD prior to initial onset of aHUS were excluded from this analysis. aHUS atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, ESKD end-stage kidney disease, HR hazard ratio, MHT malignant hypertension, mo month, PE plasma exchange, PI plasma infusion, TMA thrombotic microangiopathy

Kaplan–Meier plots for the combined endpoint of ESKD or death in patients with aHUS and MHT, stratified by age groups (adult or pediatric), are presented in Fig. 3. Figure 3a presents a comparison of adult and pediatric patients with aHUS and MHT who were treated with eculizumab, while Fig. 3b presents a comparison of adult and pediatric patients with aHUS and MHT who were not treated with eculizumab. Adult patients were at greater risk of ESKD or death than pediatric patients, and not-treated patients had worse outcomes than treated patients in both age groups.

Kaplan–Meier plots for time to ESKD or death from initial onset of aHUS for adult and pediatric patients with aHUS and MHT who were a treated with eculizumab or b not treated with eculizumab. aHUS atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome, ESKD end-stage kidney disease, MHT malignant hypertension, mo month

Discussion

This study presents data from the largest comparison of patients with aHUS with and without comorbid MHT to date. In the study population, MHT was reported as occurring at the same time as aHUS symptoms in ~ 2/3 of patients presenting with comorbid aHUS and MHT, irrespective of treatment status, and more patients with aHUS and MHT possessed pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies than patients with aHUS alone (40 [56%] vs 382 [37%]). Further, a much higher proportion of non-treated patients with aHUS and MHT had pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies (33 [65%]) compared to their treated counterparts (7 [35%]). Considering these data, and that these patients were diagnosed with aHUS, it is perhaps surprising that 51 (72%) patients with aHUS and MHT were not treated with eculizumab. However, this may partially be explained by 23 (32%) patients with aHUS and MHT and 323 (31%) patients with aHUS without MHT having a recorded onset of aHUS prior to eculizumab obtaining marketing authorization in 2011. Other possible explanations include 20 (61%) of the 33 not-treated patients with aHUS and MHT who required a kidney transplant reaching ESKD (a criterion for designating patients as not-treated in this study) prior to eculizumab availability, and some patients may also have been treated with eculizumab post-ESKD (another criterion for not-treated designation in this study). Furthermore, while eculizumab treatment status itself is not directly related to the prevalence of pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies, the results suggest that many of the patients listed as not-treated may either have reached ESKD before eculizumab became available or were not initially identified as patients with aHUS prior to ESKD. Indeed, diagnosis of aHUS may often occur late in the disease course, following TMA recurrence, a requirement for long-term dialysis, or kidney transplantation [13]. It is important to note, however, that this study only reports genetic analyses in patients who were screened and had a result reported in the registry; some patients were recorded as having been screened but no subsequent results were reported.

When the combined outcome of time to ESKD or death was assessed, both uni- and multi-variable analyses showed that significantly fewer patients with aHUS and MHT who were treated with eculizumab reached the composite endpoint, compared to not-treated patients. Further, the multi-variable analyses also highlighted that patients who presented with pathogenic genetic variants and/or anti-CFH antibodies, and patients who were adults at the time of aHUS onset, were generally at a higher risk of ESKD or death. However, many other clinical features were similar between these patient groups. As anticipated, patients from both age groups who were not-treated had worse outcomes than their treated counterparts. These results, combined with higher proportions of pathogenic genetic variants and kidney transplants in patients with aHUS and MHT—particularly those not treated with eculizumab—reiterate the importance of establishing an early and accurate diagnosis, as treating the correct patients with C5 inhibitors has been shown to substantially reduce morbidity and mortality [24,25,26,27]. However, in this analysis, fewer patients with aHUS and MHT were treated with eculizumab than patients without MHT, despite the potentially counter-intuitive increased incidence of complement gene variants in this patient population. This raises the possibility that clinicians may be continuing to regard TMA as secondary to MHT and proceed with MHT-specific treatment regimens, without considering this as a potential presentation/manifestation of aHUS/CM-TMA [9, 13, 16, 28].

One patient who presented with aHUS and MHT and was treated with eculizumab progressed to ESKD. This patient began treatment with eculizumab in September 2018 and reached ESKD in October 2019, with an interval between initiation and ESKD of 13.01 months.

In their review, Fakhouri and Frémaux-Bacchi stated that while aHUS remains, globally, a rare cause of MHT, MHT frequently complicates aHUS disease course, adding that genetic screening may not be suitable for diagnosis of aHUS as not all patients carry complement gene variants [13]. However, they commented that TMA rarely complicates the course of MHT (5–15% of cases), with the low prevalence limiting assessments of complement gene variants in patients with comorbid severe hypertension and TMA [13]. Our data are therefore important as all patients in the current analysis were diagnosed with both MHT and aHUS/TMA and were seen to have a greater prevalence of pathogenic genetic variants or anti-CFH antibodies. These results suggest that clinicians should explicitly consider genetic screening in this specific patient population. Also, while our results agree with Fakhouri and Frémaux-Bacchi that patients with aHUS can often present with MHT [13], they further suggest that a differential diagnosis of aHUS/CM-TMA should be considered in patients presenting with both MHT and TMA. This is particularly important as, in our analysis, patients with aHUS responded well to eculizumab in the presence of MHT, making an early and correct diagnosis integral to improving patient outcomes [24,25,26,27, 29]. This agrees with the paper by Karoui et al., who found that the 5-year renal survival rate was substantially lower in patients with aHUS with identified complement variants and/or hypertensive emergency than their counterparts without these complicating factors [30].

There are several potential limitations to this study—mainly in relation to the nature of registry-derived data, as previously described [23]—leading to missing/incomplete data, particularly around the recording of dates, genetic screening results, blood pressure measurements, and concomitant medication. Specifically relating to blood pressure, these data were not necessarily recorded at the time of MHT and had large variances, making conclusions difficult. Furthermore, the Global aHUS Registry only collects data on patients with a local clinical diagnosis of aHUS (not a centrally defined diagnosis) which may potentially limit the generalizability of these findings to proven CM-TMA populations. While the lack of a central definition of MHT may be a potential limitation of this study, the general clinical characteristics of MHT used for diagnosis are easily assessable and well defined.

This analysis of patients with aHUS and MHT using data from the Global aHUS Registry shows a higher prevalence of pathogenic complement variants or anti-CFH antibodies, alongside a high proportion of kidney transplantation, in patients with aHUS and MHT (particularly in not-treated patients) indicating a potential lack of early/correct diagnosis and high severity of disease in these patients when left untreated. Indeed, patients who were positive for pathogenic variants or anti-CFH antibodies were at greater risk of ESKD or death than patients without them. However, in not-treated patients with aHUS, the concurrent presence of MHT did not appear to significantly impact the risk of reaching ESKD or death, compared to not-treated patients without MHT. Moreover, MHT did not appear to affect the effectiveness of eculizumab, or baseline demographics and characteristics, compared to patients without MHT, although no formal statistical assessment of this comparison was conducted. This study also demonstrates that while clinical characteristics in patients with aHUS and MHT are similar in both pediatric and adult patients, with comparable demographics and baseline clinical measures, patients who were adults at the time of aHUS onset were at greater risk of ESKD or death than patients who were below 18 years of age at the time of aHUS onset. Lastly, the significant difference in the composite endpoint of ESKD or death between patients who were treated with complement C5 inhibition and those who were not-treated highlights the importance of an early and accurate diagnosis in these patients, to allow for the correct use of these therapeutics. Alongside a reiteration of the importance of complement C5 inhibitor therapy in patients with aHUS, the results of this study provide evidence that, in patients presenting with MHT and comorbid TMA, complement genetic screening and consideration of a differential diagnosis of aHUS are warranted to allow for prompt and correct treatment decisions.

Data statement

Alexion will consider requests for disclosure of clinical study participant-level data provided that participant privacy is assured through methods like data de-identification, pseudonymization, or anonymization (as required by applicable law), and if such disclosure was included in the relevant study informed consent form or similar documentation. Qualified academic investigators may request participant-level clinical data and supporting documents (statistical analysis plan and protocol) pertaining to Alexion-sponsored studies. Further details regarding data availability and instructions for requesting information are available in the Alexion Clinical Trials Disclosure and Transparency Policy at https://alexion.com/our-research/research-and-development. Link to Data Request Form: https://alexion.com/contact-alexion/medical-information.

Change history

03 October 2022

ESM update.

References

Fakhouri F, Zuber J, Frémeaux-Bacchi V, Loirat C (2017) Haemolytic uraemic syndrome. The Lancet 390:681–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30062-4

Campistol JM, Arias M, Ariceta G, Blasco M, Espinosa L, Espinosa M et al (2015) An update for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. A consensus document. Nefrología (English Edition) 35:421–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefroe.2015.11.006

Nester CM, Thomas CP (2012) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: what is it, how is it diagnosed, and how is it treated? Hematology 2012:617–625. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.617 (2012/1/617[pii])

Park MH, Caselman N, Ulmer S, Weitz IC (2018) Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy associated with lupus nephritis. Blood Adv 2:2090–2094. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2018019596

Brodsky RA (2015) Complement in hemolytic anemia. Blood 126:2459–2465. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-06-640995

Schaefer F, Ardissino G, Ariceta G, Fakhouri F, Scully M, Isbel N et al (2018) Clinical and genetic predictors of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome phenotype and outcome. Kidney Int 94:408–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.02.029

Nester C, Stewart Z, Myers D, Jetton J, Nair R, Reed A et al (2011) Pre-emptive eculizumab and plasmapheresis for renal transplant in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6:1488–1494. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.10181110

Khanal N, Dahal S, Upadhyay S, Bhatt VR, Bierman PJ (2015) Differentiating malignant hypertension-induced thrombotic microangiopathy from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ther Adv Hematol 6:97–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040620715571076

Timmermans SA, Abdul-Hamid MA, Vanderlocht J, Damoiseaux JG, Reutelingsperger CP, van Paassen P (2017) Patients with hypertension-associated thrombotic microangiopathy may present with complement abnormalities. Kidney Int 91:1420–1425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.009

Domek M, Gumprecht J, Lip GYH, Shantsila A (2020) Malignant hypertension: does this still exist? J Hum Hypertens 34:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-019-0267-y

Januszewicz A, Guzik T, Prejbisz A, Mikołajczyk T, Osmenda G, Januszewicz W (2016) Malignant hypertension: new aspects of an old clinical entity. Pol Arch Med Wewn 126:86–93

Aronow WS (2017) Treatment of hypertensive emergencies. Ann Transl Med 5:S5–S5. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.03.34

Fakhouri F, Frémeaux-Bacchi V (2021) Thrombotic microangiopathy in aHUS and beyond: clinical clues from complement genetics. Nat Rev Nephrol 17:543–553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00424-4

Bayer G, von Tokarski F, Thoreau B, Bauvois A, Barbet C, Cloarec S et al (2019) Etiology and outcomes of thrombotic microangiopathies. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14:557–566. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.11470918

Timmermans SAMEG, Abdul-Hamid MA, Potjewijd J, Theunissen ROMFIH, Damoiseaux JGMC, Reutelingsperger CP et al (2018) C5b9 formation on endothelial cells reflects complement defects among patients with renal thrombotic microangiopathy and severe hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol 29:2234–2243. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2018020184

Asif A, Nayer A, Haas CS (2017) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome in the setting of complement-amplifying conditions: case reports and a review of the evidence for treatment with eculizumab. J Nephrol 30:347–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-016-0357-7

Zhang K, Lu Y, Harley KT, Tran MH (2017) Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a brief review. Hematol Rep 9:7053. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2017.7053

Akimoto T, Muto S, Ito C, Takahashi H, Takeda S, Ando Y et al (2011) Clinical features of malignant hypertension with thrombotic microangiopathy. Clin Exp Hypertens 33:77–83. https://doi.org/10.3109/10641963.2010.503303

Cavero T, Arjona E, Soto K, Caravaca-Fontán F, Rabasco C, Bravo L et al (2019) Severe and malignant hypertension are common in primary atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Kidney Int 96:995–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.05.014

Fakhouri F, Sadallah S, Frémeaux-Bacchi V (2020) Malignant hypertension and thrombotic microangiopathy: complement as a usual suspect. Nephrol Dial Transplant 36:1157–1159. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa362

Lee H, Kang E, Kang HG, Kim YH, Kim JS, Kim HJ et al (2020) Consensus regarding diagnosis and management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Korean J Intern Med 35:25–40. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2019.388

Lewek J, Bielecka-Dąbrowa A, Maciejewski M, Banach M (2020) Pharmacological management of malignant hypertension. Expert Opin Pharmacother 21:1189–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2020.1732923

Licht C, Ardissino G, Ariceta G, Cohen D, Cole JA, Gasteyger C et al (2015) The global aHUS registry: methodology and initial patient characteristics. BMC Nephrol 16:207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-015-0195-1

Rondeau E, Scully M, Ariceta G, Barbour T, Cataland S, Heyne N et al (2020) The long-acting C5 inhibitor, Ravulizumab, is effective and safe in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naïve to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int 97:1287–1296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.01.035

Tanaka K, Adams B, Aris AM, Fujita N, Ogawa M, Ortiz S et al (2021) The long-acting C5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is efficacious and safe in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome previously treated with eculizumab. Pediatr Nephrol 36:889–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-020-04774-2

Licht C, Greenbaum LA, Muus P, Babu S, Bedrosian CL, Cohen DJ et al (2015) Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney Int 87:1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2014.423

Ariceta G, Dixon BP, Kim SH, Kapur G, Mauch T, Ortiz S et al (2021) The long-acting C5 inhibitor, ravulizumab, is effective and safe in pediatric patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome naïve to complement inhibitor treatment. Kidney Int 100:225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.046

Van Laecke S, Van Biesen W (2017) Severe hypertension with renal thrombotic microangiopathy: what happened to the usual suspect? Kidney Int 91:1271–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.025

Fakhouri F, Hourmant M, Campistol JM, Cataland SR, Espinosa M, Gaber AO et al (2016) Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome: a single-arm, open-label trial. Am J Kidney Dis 68:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.12.034

El Karoui K, Boudhabhay I, Petitprez F, Vieira-Martins P, Fakhouri F, Zuber J et al (2019) Impact of hypertensive emergency and rare complement variants on the presentation and outcome of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Haematologica 104:2501–2511. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.216903

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. This analysis was funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. was responsible for the collection, management, and analysis of information contained in the Global aHUS Registry. Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA contributed to data interpretation, preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript for submission. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The sponsor and investigators thank the patients and their families for their participation in, and support for, this clinical study. The authors would also like to thank all the Global aHUS Registry investigators who have contributed data, Scientific Advisory Board members of the Global aHUS Registry: Christoph Licht, Véronique Frémeaux-Bacchi, Gema Ariceta, Larry Greenbaum, Sally Johnson, Franz Schaefer, Jef Schmidt, Margriet Eygenraam and Christoph Gasteyger; and National Coordinators of the Global aHUS Registry: Miquel Blasco (Spain), Donata Cresseri (Italy), Galina Generolova (Russia), Nicholas Webb (United Kingdom), Patricia Hirt-Minkowski (Switzerland), Natalya Lvovna Kozlovskaya (Russia), Danny Landau (Israel), Anne-Laure Lapeyraque (Canada), Chantal Loirat (France), Christoph Mache (Austria), Michal Malina (Czech Republic), Leena Martola (Finland), Annick Massart (Belgium), Eric Rondeau (France), and Lisa Sartz (Sweden). The authors would like to acknowledge Alexander T. Hardy, PhD, of Bioscript, Macclesfield UK for providing medical writing support with funding from Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Radha Narayan, PhD, Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease for critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. This analysis was funded by Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA. was responsible for the collection, management, and analysis of information contained in the Global aHUS Registry. Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Boston, MA contributed to data interpretation, preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript for submission. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributed to the conception and/or design of the study, participated in the acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation of data, and in the writing, review and/or revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jean-Michel Halimi has received honoraria and/or travel grants from Ablynx; Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; AstraZeneca; Bayer; Bouchara Recordati, Fresenius; GlaxoSmithKline; Mundipharma; MSD; Roche Servier; Sanofi; and Vifor Fresenius. Imad Al-Dakkak is an employee and stockholder of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Katerina Anokhina is an employee and stockholder of Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease. Gianluigi Ardissino has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; Alnylam; Roche; Novartis; and Eligo Bioscience. Christoph Licht has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; Apellis; Genentech – Hoffman La Roche; Novartis; unrestricted research grants from Alexion, Aurin Biotech, Fresenius and Pfizer; and was Chair of the Global aHUS Registry (2013–2020). Wai Lim has received speaker fees and/or education grants from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; Novartis; and Astellas. Annick Massart has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease and Amicus Therapeutics. Franz Schaefer has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; Alnylam; Astellas; AstraZeneca; Bayer; Otsuka; Roche; and is Chair of the Global aHUS Registry. Johan Vande Walle has received honoraria from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease; Alnylam; Astellas; Bayer; Chies; Ferring; Kyowa Kyrin; Otsuka; is a member of the Global aHUS Registry; and is chair of the National aHUS Registry. Eric Rondeau has received honoraria, fees and grants from Alexion, AstraZeneca Rare Disease.

Ethical statement

This was a multicenter study comprising many different sites of enrollment. Federal, provincial, and local regulations and International Conference on Harmonization guidelines, if relevant, required that approval was obtained from an Ethics Committee (EC)/IRB prior to participation of patients in research studies. Where required and prior to the study onset, the EC/IRB must have approved the protocol, informed consent, advertisements to be used for patient recruitment, and any other written information regarding this study to be provided to the patient or the patient’s parents/legal guardian. The sites maintained and made available for review by the sponsor or its designee documentation of all EC/IRB approvals and of the EC/IRB compliance with International Conference on Harmonization Guidance E6: Good Clinical Practice, if relevant. All EC/IRB approvals were signed by the EC/IRB chairman or designee and identified the EC/IRB name and address, the clinical protocol by title and/or protocol number, and the date approval and/or favorable opinion was granted. The investigator conducted all aspects of this study in accordance with all national, provincial, and local laws of the pertinent regulatory authorities.

Informed consent

A written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to participation in the study. The sponsor or its designee could provide an informed consent template to the sites, if required. If the site made any The sponsor or its designee could provide an informed consent template to the sites, if required. If the site made any institution-specific modifications, the sponsor or its designee could review the consent prior to IRB/EC submission. The investigator or the sponsor would then submit the approved, revised consent to the appropriate IRB/EC for review and approval prior to the start of the study. If the consent form was revised during the course of the study, all active participating patients to whom the revision may have had an impact must have signed the revised form. Before recruitment and enrollment, each patient was given a full explanation of the study and was allowed time to read the approved informed consent form. Once the investigator was assured that the individual understood the implications of participating in the study, the patient was asked to give consent to participate in the study by signing the informed consent form. The investigator provided a copy of the signed informed consent to the patient. The original form was maintained in the study files at the site.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information is available on the Journal of Nephrology’s website.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Halimi, JM., Al-Dakkak, I., Anokhina, K. et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of a patient population with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome and malignant hypertension: analysis from the Global aHUS registry. J Nephrol 36, 817–828 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01465-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01465-z