Abstract

Introduction

The aims of this quality improvement project were to: (1) proactively identify people living with frailty and CKD; (2) introduce a practical assessment, using the principles of the comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), for people living with frailty and chronic kidney disease (CKD) able to identify problems; and (3) introduce person-centred management plans for people living with frailty and CKD.

Methods

A frailty screening programme, using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), was introduced in September 2018. A Geriatric Assessment (GA) was offered to patients with CFS ≥ 5 and non-dialysis- or dialysis-dependent CKD. Renal Frailty Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) meetings were established to discuss needs identified and implement a person-centred management plan.

Results

A total of 450 outpatients were screened using the CFS. One hundred and fifty patients (33%) were screened as frail. Each point increase in the CFS score was independently associated with a hospitalisation hazard ratio of 1.35 (95% CI 1.20–1.53) and a mortality hazard ratio of 2.15 (95% CI 1.63–2.85). Thirty-five patients received a GA and were discussed at a MDT meeting. Patients experienced a median of 5.0 (IQR 3.0) problems, with 34 (97%) patients experiencing at least three problems.

Conclusions

This quality improvement project details an approach to the implementation of a frailty screening programme and GA service within a nephrology centre. Patients living with frailty and CKD at risk of adverse outcomes can be identified using the CFS. Furthermore, a GA can be used to identify problems and implement a person-centred management plan that aims to improve outcomes for this vulnerable group of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges for healthcare in the twenty-first century is population ageing [1]. With population ageing comes an increasing prevalence of individuals living with multimorbidity and associated frailty, the state of vulnerability to disproportionate deterioration in health status when exposed to stressor events [2, 3]. This is relevant for all areas of healthcare, but it is especially so for specialised services, such as nephrology, that care for people living with chronic conditions that appear to hasten the decline from fitness to frailty [4]. The prevalence of frailty is far greater in those with chronic kidney disease (CKD) compared to the general older population, with one study reporting a prevalence as high as 73% in dialysis-dependent CKD [5, 6]. Importantly, frailty is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes in people with CKD, including worse health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [7] and increased hospitalisation and mortality risk [5]. Despite the high prevalence of frailty and associated risk of adverse health outcomes, proactive frailty identification is not routine practice within nephrology services. Without systematic screening, frailty is unlikely to be recognised until individuals experience an adverse event that may have been preventable with the implementation of an evidence-based intervention [8].

A 2016 clinical practice guideline recommended a ‘simple score be used on a regular basis to assess functional status in older patients with CKD’, though it stated that there was ‘no consensus on the most appropriate tool for assessing physical function in older patients with advanced CKD’ [9]. Recognising that identifying patients living with CKD and frailty is the first step towards improving outcomes for this vulnerable group, a study was performed at our centre, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (LTHTR), that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of frailty screening methods in patients with CKD [10]. This study demonstrated that the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), which is a 9-point scale with descriptions for levels of frailty [11], is an accurate frailty screening method in adults with advanced CKD [10]. The question is then what can be done to improve outcomes once an individual is screened as frail? The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) has been shown to improve outcomes for older adults when performed during an acute hospital admission; specifically, older adults are more likely to be living in their own home one year after hospitalisation [12]. It is defined as ‘a multidimensional, multidisciplinary process which identifies medical, social and functional needs, and the development of an integrated/co-ordinated care plan to meet those needs’ and is now the accepted standard of care of the older patient living with frailty [8]. Although there is limited evidence in nephrology on how best to improve outcomes for patients living with frailty and CKD, studies have demonstrated that the CGA (or a modified version) is feasible within nephrology services and can be used to identify geriatric impairments in CKD populations [13]. Once problems are identified, management strategies can be developed that aim to improve outcomes. Considering the existing evidence, our aims were to: (1) proactively identify people living with frailty and CKD; (2) introduce a practical assessment, using the principles of the CGA, for people living with frailty and CKD able to identify problems; and (3) introduce person-centred management plans for people living with frailty and CKD.

Methods

Context

The LTHTR Department of Renal Medicine participated in the Specialised Clinical Frailty Network (SCFN) delivered by National Health Service (NHS) Elect between September 2018 and September 2019 [14]. The SCFN is a quality improvement collaborative that supports healthcare teams to explore how best to integrate frailty assessment and management into care pathways. Details of the improvement collaborative are fully described at https://www.scfn.org.uk. LTHTR was one of five nephrology sites that participated in this wave of the improvement programme. All sites met on five occasions over 12 months to discuss approaches to care improvement and share quality improvement experiences. A multi-professional development group was established within the LTHTR Department of Renal Medicine in September 2018. The group met regularly during all phases of the project and adopted the model for improvement framework [15]. The project discussed hereafter is based upon the work conducted at LTHTR. Supplementary Fig. 1 illustrates the project driver diagram. Supplementary Table 1 describes the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles performed.

Awareness, education and training

Education on the relevance of frailty for nephrology services and on how to use the CFS was provided via departmental presentations (September and November 2018) and ad-hoc one-on-one sessions. An animated video was created to provide education on frailty screening, to describe the purpose of the Renal Frailty MDT and how to refer to the planned service. It was circulated within the department and displayed on LTHTR screens. The multi-professional development group collaborated with the trust End of Life Care Educator who provided bespoke training to dialysis nursing staff on how to support advance care planning discussions with patients.

Frailty screening programme

A frailty screening programme, using the CFS, was introduced within the department in September 2018. Screening was performed in LTHTR outpatient clinics, during clinical nurse specialist (CNS) home visits and on two LTHTR haemodialysis units by clinicians, CNS and dialysis staff nurses. The CFS was incorporated within a pre-existing LTHTR care tool, called the Holistic Care Tool, already used on the haemodialysis units quarterly. The Holistic Care Tool is used to assess patient functional status and psychological distress with a view to addressing problems that may otherwise remain unknown. CFS score documentation was incorporated within the trust electronic patient record system.

Geriatric Assessment

A holistic home assessment was developed using the principles of the CGA. Though it was a multi-domain assessment, it was only performed by one healthcare professional (an occupational therapist [OT] with experience performing a CGA) and therefore was termed a Geriatric Assessment (GA). The domains that were assessed during the GA included depression/anxiety, falls risk, cognition, polypharmacy, continence, skin integrity, nutrition, activities of daily living (ADLs) and social issues.

Depression and anxiety The Public Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) measures were used to screen for depression and anxiety, respectively [16, 17]. If a patient scored ≥ 3 on the first two questions of the PHQ-9 or GAD-7, the respective measure was completed in full. Scores ≥ 10 were used to signify moderate symptoms of depression and anxiety and denote a problem in this domain [16, 17].

Falls Falls risk was assessed using the Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) [18]. Individuals that scored ≥ 3 on this tool were considered at risk of falls, which represented a problem in this domain. Patients were referred to a dedicated falls clinic if the OT felt further investigation into the cause of falls was needed.

Cognition: Initially, a simple question was used to screen for cognitive impairment: ‘Has the patient been more forgetful in the last 12 months to the extent that it has significantly affected their life?’. If the answer was ‘yes’ to this screening question, the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) was performed [19]. Problems with executive function are a prominent feature of cognitive impairment in those with CKD [20]. The development group therefore later decided to incorporate the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which is a useful test of executive function [21], routinely within the GA. A score ≤ 24 was used to identify a problem in the cognition domain [22, 23]. With patient permission, a patient’s general practitioner was informed if there were concerns about cognitive impairment.

Polypharmacy Medications were reviewed and polypharmacy was defined as ≥ 5 prescribed medications [24].

Continence and skin integrity Patients who reported issues with continence or skin integrity were defined as having a problem with this domain.

Nutrition Patients who reported issues with nutrition or unintentional weight loss were defined as having a problem with this domain.

Activities of daily living ADLs were assessed by an OT during the consultation. ADLs were sub-categorised as basic ADLs (BADLs), i.e. self-care tasks, and intermediate ADLs (IADLs), i.e. tasks related to maintaining an independent household. Any reported issues performing ADLs represented a problem in this domain.

Social issues Social issues were defined as living circumstances that were considered to pose a risk to a patient’s well-being, e.g. main carer unwell and unable to meet patient’s care needs.

Renal frailty multi-disciplinary team

A Renal Frailty MDT was established that included a clinician, dialysis sister, Kidney Choices CNS, dietitian, psychologist, OT and social worker. Any staff member in the Department could refer patients for a GA. A dedicated Renal Frailty MDT email account was established and used as a single point of access for referrers. Referral criteria were modified during the project using the PDSA approach. The final established referral criteria were: age ≥ 18 years, CFS ≥ 5 (or CFS < 5 with concerns about mobility, cognition or nutritional status) and non-dialysis or dialysis dependent CKD. Patients who received a GA were discussed at a MDT meeting during which problems and associated clinical needs were discussed. A person-centred management plan was created and the MDT considered the appropriateness of starting advance care planning discussions with patients. The outcomes of MDT meetings were summarised on tailor-made pro forma and shared with the wider nephrology team involved in the patient’s care.

Measures

Screening data collected included number of patients screened each week (and individual CFS scores) between September 2018 and July 2019. Hospitalisation and mortality data were collected between September 2018 and September 2019 to assess the CFS’s ability to identify patients at risk of adverse outcomes. GA and MDT meeting data were collected between November 2018 and January 2020. Data collected included number and type of problems experienced by each patient. The rationale for doing so was to assess the ability of the GA to identify problems and thereby assess its utility. Data were collected on the number and type of actions recommended following GA and MDT meetings to assess the impact the new pathway may have on patient care.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) depending on the distribution of the data. Normal Q–Q plots were visually inspected to assess data distribution. Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. Differences in parametric data were assessed using the independent t test. Differences in non-parametric data were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The chi square test was used to assess differences in categorical data. If test assumptions were not met, between group differences for categorical data were assessed using the Fisher’s exact test. Cox regression analyses were used to assess the time to first hospitalisation and mortality hazard ratios for each unit increase in CFS score, whilst adjusting for age, sex and for non-dialysis and dialysis dependent CKD variables. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed for each model by reviewing the significance of each time-by-variable interaction. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (IBM, USA).

Results

Frailty Screening Programme

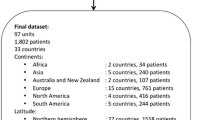

A total of 450 outpatients (366 non-dialysis and 84 haemodialysis patients) were screened using the CFS. Only first screening episodes were included in the analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of CFS Scores for patients with non-dialysis- and dialysis-dependent CKD. One hundred and fifty patients (33%) were screened as frail (i.e. CFS ≥ 5). Frail patients were older than non-frail patients (median age 81 years [IQR 14] vs. 74 years [IQR 11], p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the proportion of female (46.7% [n = 70] vs. 44.0% [n = 132], p = 0.59) and dialysis-dependent patients (16.7% [n = 25] vs. 19.7% [n = 59], p = 0.44) categorised as frail and non-frail. The median follow-up time was 210 days (95% confidence interval [CI] 203–217). More frail patients were hospitalised (41.3% [n = 62] vs. 21.3% [n = 64], p < 0.001) and died (14.7% [n = 22] vs. 1.7% [n = 5], p < 0.001) than non-frail patients. Table 1 presents the results of the Cox regression analyses. When adjusted for age, sex and dialysis dependence, each point increase in CFS score was associated with a mortality hazard ratio of 2.15 (95% CI 1.63–2.85). There was a time interaction between the non-dialysis/dialysis variable and first hospitalisation, which was therefore included in the final ‘first hospitalisation’ model (denoted as time*dialysis). When adjusted for age, sex, dialysis dependence and time*dialysis, each point increase in CFS score was associated with a first hospitalisation hazard ratio of 1.35 (95% CI 1.20–1.53).

Geriatric Assessment Service

Thirty-five patients received a GA and were discussed at a MDT meeting. Table 2 details non-dialysis- and dialysis-dependent patient demographics and clinical characteristics. The median age was 80 (IQR 19) years. There were 15 (43%) female patients who received a GA and 21 (60%) patients were receiving haemodialysis. Dialysis-dependent patients were younger than non-dialysis patients (median age 69.0 [IQR 17.5] vs. 83.5 [IQR 7.0] years, p < 0.001). The median CFS score was 6.0 (IQR 1.0). Thirty-two (91%) patients within this group had an OT-assessed CFS score ≥ 5.

Patients experienced a median of 5.0 (IQR 3.0) problems, with 34 (97%) patients experiencing at least three problems. There were more problems experienced by dialysis-dependent patients compared to non-dialysis patients (6.0 [IQR 1.5] vs 3.5 [IQR 2.0], p = 0.007). The median number of recommended actions was 4.0 (IQR 2.0), with more actions recommended for dialysis-dependent patients compared to non-dialysis patients (5.0 [IQR 2.0] vs. 3.0 [IQR 2.0], p = 0.004). Table 3 details the specific problems experienced by non-dialysis- and dialysis-dependent patients and the associated recommended actions. All patients had problems with IADLs. Twenty-six (74%) patients had at least one fall in the 12 months preceding GA and 32 (91%) patients were considered at risk of future falls. Thirteen (37%) patients had cognitive impairment. However, 10 out of the 12 patients that had a MoCA performed had a score ≤ 24. All patients received health and social care advice, for example falls prevention advice, social prescribing and signposting of available social services. Twenty-three (66%) patients were prescribed equipment to aid ADLs. The MDT recommended that advance care planning was considered for 20 (59%) patients. Despite 33 (94%) patients meeting the criteria for polypharmacy, a medication change was considered appropriate in only 2 (6%) patients. There was a higher proportion of dialysis-dependent patients experiencing problems with BADLs (71% vs 36%, p = 0.04) and nutrition (52% vs 14%, p = 0.02) than non-dialysis patients. There was also a higher proportion of dialysis-dependent patients who required the involvement of other healthcare professionals (62% vs 21%, p = 0.02) and further assessment or investigations (67% vs 21%, p = 0.01) than non-dialysis patients.

Discussion

This quality improvement project demonstrates the implementation of a novel care pathway for people living with frailty and CKD within a nephrology centre. Similar to previous reports [5], there was a high prevalence of frailty in those with CKD, with a third of all screened having a CFS score ≥ 5. This highlights the burden of frailty within our local CKD population, which prior to this project was most likely largely undetected. Each point increase in the CFS score was independently associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation and mortality. These findings are in keeping with previous studies that have evaluated the association between CFS scores and outcomes in those with CKD [25, 26]. Importantly, our results demonstrate that the CFS appropriately identified individuals at risk of adverse outcomes. It also highlights the pressing need for health services to offer interventions that aim to improve outcomes for this vulnerable patient group.

Geriatric impairments are associated with increased mortality risk in patients starting dialysis [27]. Within our cohort, there was a high prevalence of geriatric impairments identified during GA, suggesting appropriate patients were referred to the GA service. Notably, all patients experienced problems with IADLs. Previous studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of problems with IADLs in advanced CKD [28,29,30] and an association between problems with IADLs and hospitalisation and mortality [27]. Given the high prevalence of problems with IADLs, the high proportion of patients considered at risk of future falls is unsurprising. Falls are particularly concerning for those with advanced CKD, as they are associated with an increased risk of a fall-related injury compared with the non-CKD population [31] and associated with worse HRQOL [32]. Therefore, efforts to minimise future falls risk is of paramount importance for people living with frailty and CKD.

Patients receiving dialysis experienced more problems despite being younger than non-dialysis patients. Recommended actions reflected the problems identified, with more actions recommended for patients receiving dialysis. Studies have reported a high prevalence of geriatric impairments in patients receiving dialysis [28,29,30, 33, 34]. The increased prevalence of geriatric impairments in patients receiving dialysis emphasises the need for a holistic assessment, such as the CGA, in those with advanced CKD. Patients with CKD often prioritise outcomes relevant to maintaining independence and general well-being over prolonged survival [35, 36]. The identification of geriatric impairments prior to commencing dialysis treatment may influence shared-decision making between patients and nephrologists, particularly with respect to discussing the benefits and risks of dialysis treatment compared with conservative management. Further evaluation is needed to assess if interventions, such as the CGA, have a positive influence on this shared-decision making process.

There are acknowledged limitations to this quality improvement project, which is in an early stage of development. First, the cross-sectional analysis of the GA service does not allow conclusions to be made on overall benefit of the intervention. However, by implementing targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse outcomes associated with geriatric impairments, we hypothesise that there will be an associated improvement in the general health and well-being of patients. Second, validated measures were not used for all domains of the GA. The specialty group had concerns that patients would be at risk of respondent fatigue and therefore wanted to limit the number of questionnaires used to those that would be most clinically useful. A pragmatic decision was made for some domains to be assessed during the GA by an experienced OT, which reflects clinical practice. Third, a formal assessment of cognition was not used from the outset. The number of identified cases of cognitive impairment increased after introduction of the MoCA; in fact, all dialysis patients that performed a MoCA had a score ≤ 24. Therefore, the overall proportion of cognitive impairment reported is likely an under-estimation of the true prevalence of cognitive impairment in this cohort. However, this is a representative example of our PDSA approach. Finally, a validated tool was not used to assess problematic polypharmacy nor was polypharmacy assessed by a pharmacist, although medication appropriateness was assessed by a clinician.

This quality improvement project demonstrates the high burden of frailty and problems experienced by those with CKD. It also details an approach to the implementation of a frailty screening programme and GA service so that problems can be identified and a person-centred management plan developed. We encourage nephrology services to collaborate with local geriatric medicine departments and/or existing frailty teams to introduce quality improvement initiatives that aim to improve the care provided to patients living with frailty and CKD. Finally, we recommend further evaluation of the benefits of the CGA, particularly in relation to patient-reported outcomes, for patients with CKD and the impact that the CGA has on shared-decision making processes within advanced kidney care clinics.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Storey A (2018) Living longer: how our population is changing and why it matters. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/livinglongerhowourpopulationischangingandwhyitmatters/2018-08-13. Accessed 2019

Hanlon P, Nicholl BI, Jani BD, Lee D, McQueenie R, Mair FS (2018) Frailty and pre-frailty in middle-aged and older adults and its association with multimorbidity and mortality: a prospective analysis of 493 737 UK Biobank participants. Lancet Public Health 3(7):e323–e332. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30091-4

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K (2013) Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 381(9868):752–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, Woywodt A, Mitra S, Dhaygude A (2017) Frailty and chronic kidney disease: current evidence and continuing uncertainties. Clin Kidney J. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfx134

Chowdhury R, Peel NM, Krosch M, Hubbard RE (2016) Frailty and chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 68:135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.10.007

Manfredi G, Midao L, Paul C, Cena C, Duarte M, Costa E (2019) Prevalence of frailty status among the European elderly population: findings from the survey of health, aging and retirement in Europe. Geriatr Gerontol Int 19(8):723–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.13689

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, Mitra S, Brady ME, Dhaygude AP (2019) Frailty is independently associated with worse health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a secondary analysis of the frailty assessment in chronic kidney disease study. Clin Kidney J. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfz038

Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, McCleod A, Arora S, Nockels K, Kennedy S, Roberts H, Conroy S (2018) What is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing 47(1):149–155. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx166

Farrington K, Covic A, Aucella F, Clyne N, de Vos L, Findlay A, Fouque D, Grodzicki T, Iyasere O, Jager KJ, Joosten H, Macias JF, Mooney A, Nitsch D, Stryckers M, Taal M, Tattersall J, Van Asselt D, Van den Noortgate N, Nistor I, Van Biesen W (2016) Clinical Practice Guideline on management of older patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3b or higher (eGFR < 45 mL/min/1.73 m2). Nephrol Dial Transplant 31(suppl 2):ii1–ii66. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfw356

Nixon AC, Bampouras TM, Pendleton N, Mitra S, Dhaygude AP (2019) Diagnostic accuracy of frailty screening methods in advanced chronic kidney disease. Nephron 141(3):147–155. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494223

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J journal de l'Association medicale canadienne 173(5):489–495. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050051

Ellis G, Gardner M, Tsiachristas A, Langhorne P, Burke O, Harwood RH, Conroy SP, Kircher T, Somme D, Saltvedt I, Wald H, O'Neill D, Robinson D, Shepperd S (2017) Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006211.pub3

Brown EA, Farrington K (2019) Geriatric assessment in advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14(7):1091–1093. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.14771218

NHS (2018) Specialised Clinical Frailty Network. https://www.scfn.org.uk/. https://www.scfn.org.uk/. Accessed July 2020

Langley GL, Moen R, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP (2009) The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance, 2nd edn. Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2001) The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Nandy S, Parsons S, Cryer C, Underwood M, Rashbrook E, Carter Y, Eldridge S, Close J, Skelton D, Taylor S, Feder G, Falls Prevention Pilot Steering G (2004) Development and preliminary examination of the predictive validity of the falls risk assessment tool (FRAT) for use in primary care. J Public Health (Oxford, England) 26(2):138–143. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdh132

Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H (1983) Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry 140(6):734–739. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.140.6.734

Weiner DE, Gaussoin SA, Nord J, Auchus AP, Chelune GJ, Chonchol M, Coker L, Haley WE, Killeen AA, Kimmel PL, Lerner AJ, Oparil S, Saklayen MG, Slinin YM, Wright CB, Williamson JD, Kurella Tamura M (2017) Cognitive function and kidney disease: baseline data from the systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT). Am J Kidney Dis 70(3):357–367. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.04.021

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H (2005) The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4):695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

Carson N, Leach L, Murphy KJ (2018) A re-examination of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) cutoff scores. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33(2):379–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4756

Angermann S, Baumann M, Steubl D, Lorenz G, Hauser C, Suttmann Y, Reichelt AL, Satanovskij R, Sonntag F, Heemann U, Grimmer T, Schmaderer C (2017) Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients: implementation of cut-off values for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-test for feasible screening. PLoS ONE 12(10):e0184589. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184589

Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE (2017) What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 17(1):230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

Pugh J, Aggett J, Goodland A, Prichard A, Thomas N, Donovan K, Roberts G (2016) Frailty and comorbidity are independent predictors of outcome in patients referred for pre-dialysis education. Clin Kidney J 9(2):324–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfv150

Alfaadhel TA, Soroka SD, Kiberd BA, Landry D, Moorhouse P, Tennankore KK (2015) Frailty and mortality in dialysis: evaluation of a clinical frailty scale. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10(5):832–840. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.07760814

van Loon IN, Goto NA, Boereboom FTJ, Bots ML, Hoogeveen EK, Gamadia L, van Bommel EFH, van de Ven PJG, Douma CE, Vincent HH, Schrama YC, Lips J, Siezenga MA, Abrahams AC, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME (2019) Geriatric assessment and the relation with mortality and hospitalizations in older patients starting dialysis. Nephron 143(2):108–119. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501277

Goto Namiko A, van Loon IN, Moira IM, Marianne CV, Hanna CW, Mariëlle HE-V, Michiel LB, Franciscus TJB, Marije EH (2019) Geriatric assessment in elderly patients with end-stage kidney disease. Nephron 141(1):41–48. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494222

Racic M, Petkovic N, Bogicevic K, Maric I, Matovic J, Pejovic V, Kovacevic M, Djukanovic L (2015) Comprehensive geriatric assessment: comparison of elderly hemodialysis patients and primary care patients. Renal Fail 37(7):1126–1131. https://doi.org/10.3109/0886022X.2015.1057459

Hall RK, Haines C, Gorbatkin SM, Schlanger L, Shaban H, Schell JO, Gurley SB, Colon-Emeric CS, Bowling CB (2016) Incorporating geriatric assessment into a nephrology clinic: preliminary data from two models of care. J Am Geriatr Soc 64(10):2154–2158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14262

Kistler BM, Khubchandani J, Jakubowicz G, Wilund K, Sosnoff J (2018) Falls and fall-related injuries among US adults aged 65 or older with chronic kidney disease. Prev Chronic Dis 15:E82. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170518

van Loon IN, Joosten H, Iyasere O, Johansson L, Hamaker ME, Brown EA (2019) The prevalence and impact of falls in elderly dialysis patients: frail elderly patient outcomes on dialysis (FEPOD) study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 83:285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2019.05.015

Kallenberg MH, Kleinveld HA, Dekker FW, van Munster BC, Rabelink TJ, van Buren M, Mooijaart SP (2016) Functional and cognitive impairment, frailty, and adverse health outcomes in older patients reaching ESRD—a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11(9):1624–1639. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.13611215

van Loon IN, Wouters TR, Boereboom FT, Bots ML, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME (2016) The relevance of geriatric impairments in patients starting dialysis: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11(7):1245–1259. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.06660615

Urquhart-Secord R, Craig JC, Hemmelgarn B, Tam-Tham H, Manns B, Howell M, Polkinghorne KR, Kerr PG, Harris DC, Thompson S, Schick-Makaroff K, Wheeler DC, van Biesen W, Winkelmayer WC, Johnson DW, Howard K, Evangelidis N, Tong A (2016) Patient and caregiver priorities for outcomes in hemodialysis: an international nominal group technique study. Am J Kidney Dis 68(3):444–454. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.037

Ramer SJ, McCall NN, Robinson-Cohen C, Siew ED, Salat H, Bian A, Stewart TG, El-Sourady MH, Karlekar M, Lipworth L, Ikizler TA, Abdel-Kader K (2018) Health outcome priorities of older adults with advanced CKD and concordance with their nephrology providers' perceptions. J Am Soc Nephrol 29(12):2870–2878. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2018060657

Funding

Kidney Care UK funding was granted during this quality improvement project to fund a part-time OT within the Renal Frailty MDT. The funders had no role in the project design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, manuscript drafting and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACN, JB, QA, AB, JT, DB, AJD and MEB contributed to the quality improvement idea and analysis plan. ACN, JT, MH and QA contributed to the collection of data. ACN and QA performed the statistical analysis. AJD, MEB, NP, LE, SM and AB were involved in supervision/mentorship. ACN drafted the manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript revision and accepts responsibility for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. We would like to acknowledge the support received by NHS Elect representatives Mandy Rumley-Buss, Alice Clayton and Matt Tite. We would also like to acknowledge the contribution of all who have been involved in the LTHTR Renal Frailty MDT, including Rosemary Taylor, Anne Crompton, Laura Cowell, Emily Dickinson, Linda Dewhurst, Amanda Mason, Nora Kerigan, Elizabeth Coleman and Arvind Ponnusamy. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the support of Gail Naylor, Sarah Cullen, Moira Roberts and Peter McCann.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Unrelated to this body of work, APD has received lecture fees from speaking at the invitation of MSD and received travel support from Pharmacosmos. ACN reports a grant from Kidney Research UK unrelated to this project. ACN received non-financial support from the NIHR Lancashire Clinical Research Facility. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Ethics approval

The Department of Health Research and Innovation at LTHTR granted approval for this quality improvement project.

Consent to participate

As a quality improvement project, rather than a research study, formal consent to participate was not needed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nixon, A.C., Brown, J., Brotherton, A. et al. Implementation of a frailty screening programme and Geriatric Assessment Service in a nephrology centre: a quality improvement project. J Nephrol 34, 1215–1224 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00878-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-020-00878-y