Abstract

Purpose

Screening of Cushing Syndrome (CS) and Mild Autonomous Cortisol Secretion (MACS) in hypertensive patients is crucial for proper treatment. The aim of the study was to investigate screening and management of hypercortisolism among patients with hypertension in Italy.

Methods

A 10 item-questionnaire was delivered to referral centres of European and Italian Society of Hypertension (ESH and SIIA) in a nationwide survey. Data were analyzed according to type of centre (excellence vs non-excellence), geographical area, and medical specialty.

Results

Within 14 Italian regions, 82 centres (30% excellence, 78.790 patients during the last year, average 600 patients/year) participated to the survey. Internal medicine (44%) and cardiology (31%) were the most prevalent medical specialty. CS and MACS were diagnosed in 313 and 490 patients during the previous 5 years. The highest number of diagnoses was reported by internal medicine and excellence centres. Screening for hypercortisolism was reported by 77% in the presence of specific features of CS, 61% in resistant hypertension, and 38% in patients with adrenal mass. Among screening tests, the 24 h urinary free cortisol was the most used (66%), followed by morning cortisol and ACTH (54%), 1 mg-dexamethasone suppression test (49%), adrenal CT or MRI scans (12%), and late night salivary cortisol (11%). Awareness of referral centres with expertise in management of CS was reported by 67% of the participants, which reduced to 44% among non-excellence centres.

Conclusions

Current screening of hypercortisolism among hypertensive patients is unsatisfactory. Strategies tailored to different medical specialties and type of centres should be conceived.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cushing’s syndrome and Mild Autonomous Cortisol Secretion (MACS, formerly known as subclinical Cushing’s syndrome or subclinical hypercortisolism) are different aspects of the spectrum of endogenous hypercortisolism. Cushing’s syndrome is a rare disease (2–3 per million people) diagnosed in patients with cortisol excess associated with a typical clinical picture characterized by muscle weakness, striae rubrae, facial plethora, buffalo hump, and supraclavicular adiposity [1, 2]. On the other side, MACS is defined by endogenous hypercortisolism in the absence of catabolic signs of Cushing’s syndrome, representing the most frequent hormonal alteration in patients with adrenal incidentalomas [2,3,4].

Despite the differences in phenotypic expression, Cushing’s syndrome and MACS have both been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality, mostly mediated by hypertension. In Cushing’s syndrome, hypertension occurs in up to 93% of patients and can be associated with left ventricular hypertrophy, vascular atherosclerosis, and thrombosis diathesis, leading to an increased overall mortality due to venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke [5, 6]. Similarly, hypertension is the most frequent comorbidity associated with MACS (64% of the patients), and resistant hypertension has been linked to co-secretion of cortisol and corticosterone [7]. MACS have been identified as an independent risk factor for major cardiovascular events, atrial fibrillation, and increased all-cause and cardiovascular-specific mortality, with the highest risk in younger women [7,8,9,10,11]. Among hypertensive patients, Cushing’s syndrome has been diagnosed in up to 1%, whereas MACS in up to 27% of patients with resistant hypertension [12, 13].

Several previous studies have successfully demonstrated that control of hypercortisolism is key in patients with Cushing’s syndrome, through improvement or cure of hypertension and reduction of the cardiovascular risk, which however remains high even years after remission [14,15,16]. Even though the data on MACS are less solid, several evidences points toward a beneficial effect of adrenalectomy on the control of hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors [17, 18].

Nevertheless, Cushing’s syndrome is still burdened by a large diagnostic delay of up to 34 months after onset of symptoms, despite the typical clinical presentation, whereas MACS has been considered a condition without clear cardiometabolic implications until recently [19, 20]. Indeed, an early detection of endogenous hypercortisolism is of utmost importance to address the patients to proper treatments, especially among hypertensive patients.

The aim of this study was to investigate the current rate of screening and management of hypercortisolism among hypertensive patients evaluated at referral centres for hypertension in Italy, belonging to the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the Italian Society of Hypertension (SIIA).

Methods

We designed a questionnaire for physicians treating patients with hypertension, to investigate the current screening methods for hypercortisolism. The questionnaire was composed of 10 items and is provided in Supplementary Table 1. We enrolled centres belonging to the ESH and the SIIA in 14 Italian regions, to which the questionnaire was sent via institutional communication channels of the Societies, with the help of the regional sections and the ARCA (Associazioni Regionali Cardiologi Ambulatoriali) Piemonte. Participating centres were divided into excellence centres (centres certified by the Societies as reference centre for care of hypertension) and non-excellence centres.

Data were presented as descriptive statistics for the whole cohort of participating centres. Data were also analyzed after stratification by geographical area (North Italy vs Centre-South Italy), prevalent specialty of the responding physicians (Internal Medicine vs Cardiology vs other), and type of the centres (excellence vs non-excellence centres).

Statistical analysis was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data are presented as median and interquartile range, or frequencies, as appropriated. Comparison among groups was performed by Chi-square or Fisher’s tests for categorical variables, and with Kruskal–Wallis or Mann–Whitney tests for scalar variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 82 centres were involved, as shown in Table 1. Most of the responding centres were located in the north of Italy (63%). About one third (30%) was labelled as excellence centre. The most prevalent medical specialty was internal medicine (44%), followed by cardiology (31%), while endocrinologists represented 10% (n = 8 centres) of the total responders (Fig. 1).

The total number of patients evaluated by all centres during the year before the date of response was 78.790, of which 21.890 as first evaluations. The average number of patients referred per year to each centre was 600 (range 300–1500), with 10% (range 5–25%) of subjects having resistant hypertension. The number of patients diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome and MACS during the last five years was 313 and 490, respectively, with a median of 1 case for both diseases. The proportion of centres that did not report diagnoses of Cushing’s syndrome and MACS during the last five years was 39% (32/82) and 50% (41/82), respectively. The analysis of those parameters according to geographical area did not highlight significant differences, whereas when considering the prevalent medical specialty, a higher number of patients diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome during the last 5 years was recorded by internal medicine specialists (P = 0.009), when compared to other groups (Supplementary Table 2). Excellence centres had a higher average number of patients per year than those labeled as non-excellence and a higher number of patients diagnosed with Cushing’s syndrome and MACS.

Table 2 shows the results of the questions on the diagnosis and management of hypercortisolism. Among all, 63/82 (77%) of the centres would perform a hormonal evaluation in the presence of hypertension and specific features of Cushing’s syndrome, whereas 50/82 (61%) would do so in the presence of resistant hypertension. Importantly, only 31/82 (38%) of the centres would ask for hormonal evaluation in the case of hypertension and adrenal mass. When the suspicion of hypercortisolism leads to hormonal assessment, the 24 h urinary free cortisol (24 h-UFC) is the most frequent test (66%), followed by basal (i.e. morning) cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) (54%), 1 mg-dexamethasone suppression test (DST) (49%), and late night salivary cortisol (LNSC) (11%). Remarkably, adrenal computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was considered as a screening tool for hypercortisolism by 10/82 centres (12%). Most centres (57/82, 67%) were aware of a referral centre with expertise in the management of Cushing’s syndrome in their area.

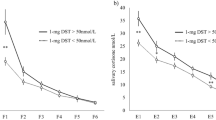

The analysis by geographical area did not highlight significant differences, except that no centres in the center-south of Italy would request the evaluation for hypercortisolism in patients with hypertension and obesity (Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 2). The analysis according to the prevalent specialty of responding physicians (Table 3 and Fig. 3) revealed a lower proportion of screening among cardiologists than others for patients with hypertension and adrenal mass (P < 0.001) and resistant hypertension (P = 0.004), as well as a higher rate of referral to the endocrinologists (P = 0.034). The 1-mg DST was the most frequent test requested by internal medicine centres (61%), when compared to cardiology (32%) and other (48%) centres (P = 0.003). No significant differences were detected for the use of other tests, confirming the data of the whole cohort. A higher proportion of centres not aware of a reference centre for Cushing’s syndrome was detected among cardiologists (48%) (P = 0.031).

Responses to questions 6–9 of the questionnaire after stratification for prevalent medical specialty. Data are reported as absolute numbers and frequencies, as appropriate. P-value < 0.05 were considered significant and highlighted in bold. See also Table 3. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

The sub analysis by prevalent medical specialty was performed also considering the 8 centres of endocrinology as a separate group (data not shown). All the endocrinological centres would screen for hypercortisolism in the presence of patients with hypertension and adrenal mass, as well as patients with resistant hypertension (P < 0.001 for both). A significant higher proportion of endocrinology centres would prefer the 1 mg DST and LNSC as screening tools for hypercortisolism (P = 0.004 and P = 0.032, respectively).

No significant differences in the categories of patients to be screened for hypercortisolism nor in the preferred screening tests were detected between excellence vs non-excellence centres. Almost half of non-excellence centres (25/57, 44%) was not aware of a referral centre with expertise in the management of Cushing’s syndrome in their area (P < 0.001 vs excellence centres, 0%) (Supplementary Table 4 and Fig. 4). Among those, 40% of the centres (n = 10) would refer a patient with a cortisol after 1 mg DST > 2.5 mcg/dL to an endocrinologist. Similarly, the proportion of non-excellence centres that are aware of a referral centre for Cushing’s syndrome that would refer a patient with such a hormonal profile to an endocrinologist was 56% (n = 18).

Discussion

This study provides the results of a survey on the diagnosis and management of hypercortisolism, among Italian centres affiliated to SIIA and ESH managing patients with hypertension. The survey covered a large proportion of Italian territory, by involving 82 centres in 14 regions with almost 80.000 patients, representing a large population in a real-life setting (the proportion of resistant hypertension was in line with the literature) [21, 22].

The survey highlighted that screening of hypercortisolism still remains an issue across different medical specialties. Importantly, roughly one third of the centres would not screen for hypercortisolism even in the presence of hypertension and specific features of Cushing’s syndrome. This holds true independently of geographical distribution of the centre, prevalent medical specialty or type of the centre (excellence vs non-excellence). An impressive high proportion of underscreening has also been identified in patients with hypertension and adrenal mass (60% of the centres). Notably, young hypertensive patients < 50 years are not undergoing screening for hypercortisolism in the majority of the centres (roughly 70%), with no difference among medical specialists. A large rate of underscreening of hypercortisolism was also identified in patients with resistant hypertension (40% of the centres), with an even higher proportion of underscreening among cardiologists. Even if the data collection was not planned for calculating the prevalence of cases of Cushing’s syndrome and MACS among hypertensive patients, some estimates can be extrapolated. When only first evaluations of patients were considered (since the likelihood of diagnosing hypercortisolism might be higher in this category of patients), the prevalence of new diagnoses is 0.3% (average of 63 cases/21.890 patients/year) for Cushing’s syndrome and 0.5% (average of 98 cases/21.890 patients/year) for MACS. Those numbers are much lower than expected, since the prevalence of Cushing’ s syndrome and MACS among hypertensive patients was up to 2% and 1–8%, respectively, in previous studies [23,24,25]. The proportion of patients receiving a diagnosis of hypercortisolism among the total cohort of patients evaluated by the centres are even lower (0.08% for Cushing’s syndrome and 0.12% for MACS).

According to the current guidelines, patients with specific features of hypercortisolism, like easy bruising, facial plethora, striae rubrae, myopathy or weakness in proximal muscles and unusual features for age, should all be screened for Cushing’s syndrome [1, 2, 16, 26]. The presence of these features, in combination with other signs or symptoms potentially related to hypercortisolism, even if less specific, increase the pre-test probability of Cushing’s syndrome, and should prompt a rapid screening for hypercortisolism. In particular, some specific characteristics associated with hypercortisolism has been recognized among hypertensive patients. In a recent consensus published by the working group on secondary hypertension of the ESH, the screening of Cushing’s syndrome should be performed in young patients (< 40 years) with at least grade 2 hypertension, children with hypertension, subjects with resistant hypertension independently of age, and patients with non-dipping blood pressure profile [16]. Moreover, the presence of hypokalemia should also prompt the screening for hypercortisolism. Furthermore, the analysis of white blood cells might also be helpful in the screening of Cushing’syndrome, according to recent data [27, 28]. Patients with adrenal incidentalomas should be screened all for MACS, independently of the presence of specific features of Cushing’s syndrome. MACS is not associated with catabolic signs of Cushing’s syndrome, by definition. However, hypertension is frequently associated with this disorder, with a pooled relative risk of 1.24 (95% confidence interval 1.16–1.32) in 31 studies, when MACS is defined by cortisol levels after 1 mg-DST > 1.8 µg/dL) [29].

According to the results of this survey, when the screening of hypercortisolism is planned, among the three screening tests for Cushing’s syndrome, 24 h-UFC is the most frequently used, followed by 1 mg DST and LNSC, the latter performed almost exclusively by endocrinologists. 24 h-UFC is being largely used for screening of Cushing’s syndrome, since it reflects the 24 h urinary output of free cortisol, with a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 93% [30]. Nevertheless, incomplete urine collection and impaired GFR may lead to false negative results. Therefore, confirmation by a repeated urinary free cortisol assay is suggested by the guidelines, even though intra-individual variations of cortisol excretion is an issue that should be taken into account when interpreting the results [1, 2, 16, 31]. The 1 mg DST has shown a high sensitivity (99%) with a specificity of 91% for diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome [30]. Given the high sensitivity at the cortisol cut off of 1.8 µg/dL, the 1 mg DST is appropriate for screening purposes, after having excluded potential sources of bias (incomplete or lack of ingestion of dexamethasone by the patient, changes in cortisol binding globulin or albumin, and drugs altering the CYP3A4 activity) [31]. Collection of LNSC is a simple and non-invasive test that can be performed at home by the patients, with sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome > 90% [32]. The reliability of this test may be reduced by night shifts or altered sleep–wake cycles, blood contamination of the sample, and large intra-individual variability, therefore repeated sampling is suggested by the guidelines [1, 2]. Considering the performance and the pitfalls of each test, a larger use of LNSC is desirable as a valid method for improving the low screening rate of Cushing’s syndrome among hypertensive patients.

Although 24 h-UFC and LNSC are appropriate for screening Cushing’s syndrome, they are not valid methods for diagnosing MACS, because those tests may be often normal in this condition [2]. According to the most recent guidelines, MACS should be diagnosed by using 1 mg DST as a single test, by using a revised cut off for cortisol of 1.8 µg/dL, without further grading of severity based on additional hormonal tests [2].

It is noteworthy that an important proportion of centres use inappropriate tool for screening hypercortisolism, like morning ACTH and cortisol (roughly half of the centres) and CT or MRI scan (12% of responders). Baseline ACTH and cortisol should not be considered as screening tests for hypercortisolism, because ACTH may be within the normal range in pituitary Cushing’s syndrome and morning cortisol may not be elevated. Morning ACTH is a useful test for subtyping Cushing’s syndrome, once the diagnosis has been established by appropriate testing [1, 2]. The use of imaging as a screening tool rise the possibility to detect incidentalomas, which are very common and are not necessarily associated with hypercortisolism. In particular, adrenal incidentalomas are discovered in 3–4.2% of patients undergoing abdominal imaging and pituitary incidentalomas in 15–21 per 100.000 in the general population (16–36% of pituitary adenomas) [3, 33].

The results of the survey also highlight an inappropriate referral to proper centres of patients with hypercortisolism. Indeed, half of the non-excellence centres are not aware of a centre with expertise in Cushing’s syndrome (a situation dramatically different from the excellence centres, with 100% of awareness) and less than half of them would refer a patient with hypercortisolism to an endocrinologist. These data point toward an insufficient network of collaboration between non-excellence centres managing patients with hypertension and tertiary endocrinological centres, leading to a referral of patients with hypercortisolism that is insufficient (60% of the patients are not addressed to an expert endocrinological centre) and inappropriate (the remaining patients are referred to endocrinologists who are likely not expert in managing Cushing’s syndrome).

Therefore, the survey highlights an unsatisfactory screening rate for Cushing’s syndrome among hypertensive patients, which may explain in part the reason for the delay in the diagnosis of this condition [19]. The prompt recognition of Cushing’s syndrome is pivotal, to address the patient to a proper treatment to control the hormonal excess and manage hypertension, since the latter has been associated independently with increased mortality and duration and severity of hypercortisolism [5, 34,35,36]. Even though the association between hypertension and MACS is based mostly on retrospective and observational data, two randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that adrenalectomy may be effective in improving blood pressure in hypertensive patients with adrenal incidentalomas and MACS [15, 16]. Ongoing studies will provide more data on the efficacy of surgical (NCT02364089) [37] and medical treatment with steroidogenesis inhibitors (EudraCT: 2019–002008-41) [38] on hypertension in MACS (a full list of trials is available at clinicaltrials.gov).

The main limitation of this study is that the results were based on a self-reported survey, without a through revision of the data provided by each centre. However, this approach is appropriate to understand the current management of hypercortisolism among patients with hypertension on a large scale. Moreover, we did not investigate the referral rate to hypertensive centres from general practitioners. Indeed, the strength of this study are the large number of centres involved, spanning across the country, with a well-balanced representation of excellence and non-excellence centres.

Conclusions

The current screening of hypercortisolism among hypertensive patients is still unsatisfactory. The results of this study provides a basis for planning future strategies to improve the screening rate of this condition by increasing the knowledge about the relationship between hypercortisolism and hypertension, and tailoring the choice of more appropriate screening tools based on the clinical setting (clinical suspicion of Cushing’s syndrome or adrenal incidentalomas), convenience for patients and physicians, and accuracy. These strategies should be targeted according to the different medical specialties and the type of centre.

Data availability

Data are available on request.

References

Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, Ben-Shlomo A, Bertherat J, Biermasz NR et al (2021) Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol dicembre 9(12):847–875

Fassnacht M, Tsagarakis S, Terzolo M, Tabarin A (2023) European Society of endocrinology clinical practice guidelines on the management of adrenal incidentalomas, in collaboration with the European network for the study of adrenal tumors. Eur J Endocrinol 189(1):G1-42

Sherlock M, Scarsbrook A, Abbas A, Fraser S, Limumpornpetch P, Dineen R et al (2020) Adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr Rev 41(6):775–820

Sconfienza E, Tetti M, Forestiero V, Veglio F, Mulatero P, Monticone S (2023) Prevalence of Functioning Adrenal Incidentalomas: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 108(7):1813

Pivonello R, Isidori AM, De Martino MC, Newell-Price J, Biller BMK, Colao A (2016) Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: state of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol luglio 4(7):611–629

Dekkers OM, Horváth-Puhó E, Jørgensen JOL, Cannegieter SC, Ehrenstein V, Vandenbroucke JP et al (2013) Multisystem morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab giugno 98(6):2277–2284

Di Dalmazi G, Fanelli F, Zavatta G, Ricci Bitti S, Mezzullo M, Repaci A et al (2019) The steroid profile of adrenal incidentalomas: subtyping subjects with high cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104(11):5519–5528

Di Dalmazi G, Vicennati V, Garelli S, Casadio E, Rinaldi E, Giampalma E et al (2014) Cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with adrenal incidentalomas that are either non-secreting or associated with intermediate phenotype or subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: a 15-year retrospective study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol maggio 2(5):396–405

Morelli V, Palmieri S, Lania A, Tresoldi A, Corbetta S, Cairoli E et al (2017) Cardiovascular events in patients with mild autonomous cortisol secretion: analysis with artificial neural networks. Eur J Endocrinol luglio 177(1):73–83

Di Dalmazi G, Vicennati V, Pizzi C, Mosconi C, Tucci L, Balacchi C et al (2020) Prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large cohort of adrenal incidentalomas: A long-term study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa270

Deutschbein T, Reimondo G, Dalmazi GD, Bancos I, Patrova J, Vassiliadi DA et al (2022) Age-dependent and sex-dependent disparity in mortality in patients with adrenal incidentalomas and autonomous cortisol secretion: an international, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 10(7):499–508

Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T (2004) Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. Hypertens Res 27(3):193–202. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.27.193

Martins LC, Conceição FL, Muxfeldt ES, Salles GF (2012) Prevalence and associated factors of subclinical hypercortisolism in patients with resistant hypertension. J Hypertens 30(5):967–973. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283521484

Colao A, Pivonello R, Spiezia S, Faggiano A, Ferone D, Filippella M et al (1999) Persistence of increased cardiovascular risk in patients with Cushing’s disease after five years of successful cure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84(8):2664–2672

Nieman LK, Biller BMK, Findling JW, Murad MH, Newell-Price J, Savage MO et al (2015) Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(8):2807–2831

Fallo F, Di Dalmazi G, Beuschlein F, Biermasz NR, Castinetti F, Elenkova A et al (2022) Diagnosis and management of hypertension in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: a position statement and consensus of the Working Group on Endocrine Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens novembre 40(11):2085

Iacobone M, Citton M, Viel G, Boetto R, Bonadio I, Mondi I et al (2012) Adrenalectomy may improve cardiovascular and metabolic impairment and ameliorate quality of life in patients with adrenal incidentalomas and subclinical Cushing’s syndrome. Surgery 152(6):991–997

Morelli V, Frigerio S, Aresta C, Passeri E, Pugliese F, Copetti M et al (2022) Adrenalectomy improves blood pressure and metabolic control in patients with possible autonomous cortisol secretion: results of a RCT. Front Endocrinol 13:898084

Rubinstein G, Osswald A, Hoster E, Losa M, Elenkova A, Zacharieva S et al (2020) Time to diagnosis in Cushing’s syndrome: a meta-analysis based on 5367 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz136

Reincke M, Fleseriu M (2023) Cushing syndrome: a review. JAMA 330(2):170–181

Carey RM, Sakhuja S, Calhoun DA, Whelton PK, Muntner P (2019) Prevalence of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension in the United States. Hypertension febbraio 73(2):424–431

Yoon M, You SC, Oh J, Lee CJ, Lee SH, Kang SM et al (2022) Prevalence and prognosis of refractory hypertension diagnosed using ambulatory blood pressure measurements. Hypertens Res agosto 45(8):1353–1362

Anderson GH, Blakeman N, Streeten DH (1994) The effect of age on prevalence of secondary forms of hypertension in 4429 consecutively referred patients. J Hypertens maggio 12(5):609–615

Omura M, Saito J, Yamaguchi K, Kakuta Y, Nishikawa T (2004) Prospective study on the prevalence of secondary hypertension among hypertensive patients visiting a general outpatient clinic in Japan. Hypertens Res Off J Jpn Soc Hypertens. 27(3):193–202

Martins LC, Conceição FL, Muxfeldt ES, Salles GF (2012) Prevalence and associated factors of subclinical hypercortisolism in patients with resistant hypertension. J Hypertens maggio 30(5):967–973

Braun LT, Vogel F, Zopp S, Marchant Seiter T, Rubinstein G, Berr CM et al (2022) Whom should we screen for Cushing syndrome? The endocrine society practice guideline recommendations 2008 revisited. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 107(9):e3723–e3730

Ambrogio AG, De Martin M, Ascoli P, Cavagnini F, Pecori GF (2014) Gender-dependent changes in haematological parameters in patients with cushing’s disease before and after remission. Eur J Endocrinol 170(3):393–400. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-13-0824

Detomas M, Altieri B, Chifu I, Remde H, Zhou X, Landwehr LS, Sbiera S, Kroiss M, Fassnacht M, Deutschbein T (2022) Subtype-specific pattern of white blood cell differential in endogenous hypercortisolism. Eur J Endocrinol 187(3):439–449. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-22-0211

Pelsma ICM, Fassnacht M, Tsagarakis S, Terzolo M, Tabarin A, Sahdev A et al (2023) Comorbidities in mild autonomous cortisol secretion and the effect of treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 189(4):S88-101

Galm BP, Qiao N, Klibanski A, Biller BMK, Tritos NA (2020) Accuracy of laboratory tests for the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105(6):2081–2094

Petersenn S (2022) Overnight 1 mg dexamethasone suppression test and 24 h urine free corticy and pitfalls when screening for Cushing’s syndrome. Pituitary 25(5):693–697

Balomenaki M, Margaritopoulos D, Vassiliadi DA, Tsagarakis S (2022) Diagnostic workup of Cushing’s syndrome. J Neuroendocrinol 34(8):e13111

Watanabe G, Choi SY, Adamson DC (2022) Pituitary incidentalomas in the united states: a national database estimate. World Neurosurg 158:e843–e855

Mancini T, Kola B, Mantero F, Boscaro M, Arnaldi G (2004) High cardiovascular risk in patients with Cushing’s syndrome according to 1999 WHO/ISH guidelines. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 61(6):768–777

Giordano R, Picu A, Marinazzo E, D’Angelo V, Berardelli R, Karamouzis I et al (2011) Metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with Cushing’s syndrome of different aetiologies during active disease and 1 year after remission. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 75(3):354–360

Clayton RN, Raskauskiene D, Reulen RC, Jones PW (2011) Mortality and morbidity in Cushing’s disease over 50 years in stoke-on-trent, UK: audit and meta-analysis of literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(3):632–642

Surgery of Subclinical Cortisol Secreting Adrenal Incidentalomas (CHIRACIC). ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02364089. 2015. Sponsor: University Hospital, Bordeaux.

Effect of the treatment with Metyrapone on the cardiovascular risk in patients with adrenal incidentalomas and subclinical Cushing's syndrome. EudraCT: 2019-002008-41. 2019. Sponsor: IRCCS S. Orsola Policlinic, University of Bologna, Bologna

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants to this survey from the Italian Society of Hypertension (SIIA) and the cardiologists of the Associazione Regionale Cardiologi Ambulatoriali (ARCA) Piemonte.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studie with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Dalmazi, G., Goi, J., Burrello, J. et al. Screening of hypercortisolism among patients with hypertension: an Italian nationwide survey. J Endocrinol Invest (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-024-02387-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-024-02387-2