Abstract

Context

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is clinically heterogeneous. The genotype and phenotype correlation has not been well established. Though the long-term prognosis is considered to be favorable, hypokalemia is difficult to cure.

Objective

To analyze the clinical and genetic characteristics and treatment of all members of 13 GS pedigrees.

Methods

Thirteen pedigrees (86 members, 17 GS patients) were enrolled. Symptoms and management, laboratory findings, and genotype–phenotype associations among all the members were analyzed.

Results

The average ages at onset and diagnosis were 27.6 ± 10.2 years and 37.9 ± 11.6 years, respectively. Males were an average of 10 years younger and exhibited more profound hypokalemia than females. Eighteen mutations were detected. Two novel mutations (p.W939X, p.G212S) were predicted to be pathogenic by bioinformatic analysis. GS patients exhibited the lowest blood pressure, serum K+, Mg2+, and 24-h urinary Ca2+ levels. Although blood pressure, serum K+ and Mg2+ levels were normal in heterozygous carriers, 24-h urinary Na+ excretion was significantly increased. During follow-up, only 41.2% of patients reached a normal serum K+ level. Over 80% of patients achieved a normal Mg2+ level. Patients were taking 2–3 medications at higher doses than usual prescription to stabilize their K+ levels. Six patients were taking spironolactone simultaneously, but no significant elevation in the serum K+ level was observed.

Conclusion

The phenotypic variability of GS and therapeutic strategies deserve further research to improve GS diagnosis and prognosis. Even heterozygous carriers exhibited increased 24-h Na+ urine excretion, which may make them more susceptible to diuretic-induced hypokalemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gitelman syndrome (GS, OMIM 263800), one of the most common hereditary disorders of potassium homeostasis, is characterized by hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalciuria without hypertension [1, 2]. The prevalence of GS is approximately 1–10 per 40,000 people, and, accordingly, the prevalence of heterozygotes is approximately 1% in Western countries [3, 4]. In Asia, the prevalence of GS increases to an astonishing 10.3 per 10,000 people [5], and the prevalence of mutations may be as high as 3% [3].

Inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, GS is caused by inactivating mutations in the solute carrier family 12 member 3 gene (SLC12A3, Gene ID: 6559; MIM: 600968; Gene Bank: NC_000016.10), which encodes the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) [6]. To date, 453 mutations have been deposited in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/). Interestingly, the phenotype of GS patients is highly heterogeneous [7]. Some researchers have analyzed the clinical and genetic characteristics in unrelated patients with GS. However, a comprehensive genotype and phenotype correlation has not been well established. Moreover, pedigree members have identical geographic backgrounds and similar dietary habits. The careful study of GS pedigrees may help to obtain more valuable information about this disorder.

The long-term prognosis of GS is considered to be favorable. However, hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia in GS are difficult to cure. Patients exhibit a significantly reduced quality of life due to the presence of several unspecific symptoms, such as salt cravings, thirst, dizziness, fatigue, muscle weakness, cramps, paresthesias, nocturia, polydipsia, and polyuria. Compared with the typical population, patients with GS may be at increased risk for the development of chronic kidney disease and type 2 Diabetes [8]. Therefore, follow-up study is imperative for in-depth research to seek out a better method for GS treatment and to prevent further exacerbation of the disease.

Thus, we analyzed the clinical and genetic characteristics among all the members of 13 GS pedigrees, and continuous follow-up was performed for about 3 years to accumulate valuable data on the treatment of GS. Our research may assist in the understanding of phenotypic variability and provide useful insight into the characteristics of GS as well as therapeutic strategies for this disease.

Subjects and methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University, and all the participants have signed the written informed consent before participation. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Subjects

The study group consisted of 13 pedigrees, including 86 members, of whom 17 were GS patients (9 males and 8 females, age 39.5 ± 11.9 years) (Fig. 1). Diagnostic criteria for GS include the following: hypokalemia (serum K+ < 3.5 mmol/L) with inappropriate renal potassium wasting; hypomagnesemia (serum Mg2+ < 0.7 mmol/L) with inappropriate renal magnesium wasting; hypocalciuria (urine Ca2+/Cr ratio < 0.2 mmol/mmol); metabolic alkalosis; high plasma renin activity or levels; low or normal–low blood pressure [1]. None of them had history of long-term use of diuretics and laxatives or alcohol or drug addiction. Other extrarenal and renal causes of hypokalemia such as Cushing’s syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism, tubular acidosis, history of nephrotoxic drugs or liquorice intake, stenosis of the renal artery and transcellular shift of K+ such as thyrotoxic or familial periodic paralysis, the use of bronchodilators, were also excluded.

Clinical data analysis

We collected the clinical symptoms of all patients and laboratory findings among all the members of 13 GS pedigrees. Clinical symptoms include general (fatigue, dizziness/vertigo, fainting, and exercise intolerance), musculoskeletal (weakness, muscle stiffness or pain, muscle cramps, carpopedal spasm/tetany, and paralysis), renal (nocturia, polyuria, polydipsia, thirst, enuresis, and salt craving), gastrointestinal (vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain), cardiovascular (palpitation and chest pain), and neurological symptoms (paresthesia and tremor) as previously described [9]. Severe GS was defined if patients showed at least three category symptoms at the same time, while mild GS was limited to fewer than three category manifestations. Biochemical values included concentration of serum K+, Mg2+, urine Ca2+/Cr, 24-h urinary Ca2+, Na+, K+ levels and blood pressure.

Mutation analysis of the SLC12A3 gene

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, DP 304-03). Twenty-two pairs of primers were generated to amplify the whole SLC12A3 gene, including all exons and intron–exon boundaries. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in a 50 μL system including 4 μL dNTP, 5 μL 10 × PCR buffer, 0.3 μL Taq Hot Start (Takara Bio, Ohtsu, Japan), 4 μL genomic DNA and 1 μl forward and reverse primers. The reaction condition contained an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 5 min subsequently followed by 40 cycles with denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s and elongation at 72 °C for 30 s. PCR products were directly sequenced on an ABI 3730XL DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif., USA). Sequence analysis was finished through Auto Assembler software Chromas 2.0. Recurrent mutation was defined as the same mutation reappearing in at least two unrelated pedigrees.

Bioinformatic analysis

We performed sequence alignment of NCC homologous proteins on eight species to confirm the conservation of mutated positions. To determine potential effects of the two novel mutations on NCC function, online softwares such as Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), Poly Phen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.arvard.edu/pph2) and SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/) were employed. Modeling of wild type and mutant protein was achieved using I-TASSER workspace (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/), and PyMOL Viewer was used to visualize the effect of novel mutations on the protein configuration of NCC.

Follow-up studies

All patients were reviewed by phone every 2 months to record symptoms. Biochemical examinations were performed in local hospitals every 6 months, and face-to-face follow-ups in our hospital were completed once a year. If there were special circumstances (such as hypokalemic acute attack), patients were taken to a nearby hospital for examination and treatment. The other members of all pedigrees were asked about the symptoms every 6 months and tested above the biochemical indices once a year. Pedigrees were followed for 1.9 ± 1.1 years. We also closely tracked the occurrence of potential complications and evolution such as glucose metabolism and impaired renal function.

Statistical analyses

Values were expressed as the mean ± SD. Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to compare the variables between the male and female patients. To determine the correlation between genotypes and phenotypes, Student’s t test was used to compare their differences. We used one-way ANOVA to explore the effect of SLC12A3 mutations on blood pressure and laboratory parameters in all pedigree members. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

Characteristics of the patients

As shown in Table 1, the average ages at onset and diagnosis of GS were 27.6 ± 10.2 years and 37.9 ± 11.6 years, respectively. The duration from onset to diagnosis was 10.4 ± 9.4 years, indicating a long period of underdiagnosis. Interestingly, the age of onset in males was 10 years earlier than that in females (male vs. female, 22.7 ± 8.8 years vs. 33.9 ± 8.6 years, P < 0.05). Clinically, muscle paralysis (47%), fatigue (41.2%), paresthesia (35.3%), muscle weakness (29.4%), palpitation (23.5%), cramps (17.6%), and tetany (17.6%) were common symptoms. Usually, muscle paralysis was the primary presenting symptom in affected males. In contrast, fatigue was more common in females (P < 0.05). Six patients (35.3%) had severe symptoms, with men accounting for most of them (five males, one female), which indicated that males had more severe symptoms than females. One male (patient pedigree FII-1) and one female (patient pedigree GII-3) were virtually asymptomatic.

Hypokalemia (2.53 ± 0.40 mmol/L) was present in all the patients. Among them, approximately 50% of the patients had severe hypokalemia and 35.3% of them had moderate hypokalemia. Hypomagnesemia was also found in the majority of the patients, with an average level of 0.52 ± 0.14 mmol/L. Similarly, urine Ca2+/Cr decreased to less than 0.2 in 88.2% of patients, with two exceptions. Consistent with clinical symptoms, males had more significant hypokalemia than females (2.31 ± 0.24 mmol/L vs. 2.77 ± 0.43 mmol/L, P < 0.05), while there was no significant difference in the plasma Mg2+ (P > 0.05) and urine Ca2+/Cr (P > 0.05) levels between men and women. All patients had normal blood pressure.

Genotype analysis

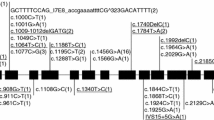

A total of 18 mutants were detected (Fig. 2a). All detected mutations are summarized in Table 2. There were nine missense, two nonsense, three deletion, one insertion, one insertion and deletion, and two splice-site/intronic mutations which incurred in intron–exon boundaries. In agreement with previous reports, the majority of our patients had a compound heterozygous mutation on two alleles. Nevertheless, one patient (pedigree M II-1) had three NCC mutations, and two patients (pedigree A II-1 and J II-1) from two different families had only one heterozygous mutation. We found four recurrent mutations, including T163 fs, c.506-1G > A, D486 N and T60 M, which means that these mutations were probably common in Chinese patients with GS.

Mutation analysis of SLC12A3. a Schematic diagram of the NCC and mutations identified in 13 Chinese GS pedigrees. NCC is represented as a 12-transmembrane-domain protein with intracytoplasmic amino and carboxyl termini. The sites of mutations are denoted by arrows and special marks like *, Δ, #. Novel mutants are underlined. *c.486_490delinsA, Δc.506-1G >A, #c.805_806insTTGGCGTGGTCTCGGTCA. b Two novel mutations. c Cross-species conservation of SLC12A3 around G212 and W939X

Interestingly, two novel mutations were identified in pedigree A patient II-1 (c.2816G > A, p.W939X) and pedigree F patient II-1 (c.634G > A, p.G212S). As shown in Fig. 2b, patient A II-1 inherited the only variant from his mother, while in patient F II-1, the novel variant was from his father and the other one from his mother. The missense mutation, G > A at nucleotide 634, led to a predicted amino acid substitution from glycine to serine at codon 212 of the proband in a heterozygote state. This mutation was strongly predicted to be pathogenic using three web-based programs—Mutation Taster, PolyPhen-2, and SIFT. The nonsense mutation (c.2816G >A) was predicted to result in a premature stop codon at amino acid 939 (p.W939X), leading to a truncated protein, which was 83 amino acids shorter than the wild type. This mutation was predicted to be probably damaging by Mutation Taster. According to the sequencing alignment, the locations of both G212 and W939 were highly conserved among all eight species (Fig. 2c). Moreover, both p.G212S and p.W939X were predicted to alter the protein’s three-dimensional structure by the I-TASSER workspace program (Fig. 3). G212S led to the exposure of carbon bonds between two alpha helices, which may affect the modification of NCC protein or its interaction with other proteins. W939X caused the deletion of 83 amino acids at the carboxyl terminus, so its three-dimensional structure changed significantly, especially the carbon terminal conformation. All of this information suggested that these two novel mutations can destroy the structure of NNC, leading to functional defects.

Correlation between phenotype and genotype among patients

Based on the type of genotype, we further stratified patients into subgroups. As shown in Table 3, serum potassium levels were lower in patients with intronic mutations (intronic mutations vs. nonintronic mutations, 2.22 ± 0.26 vs. 2.70 ± 0.37 mmol/L, P < 0.05) or nonframeshift mutations (frameshift mutations vs. nonframeshift mutations, 2.74 ± 0.43 vs. 2.33 ± 0.27 mmol/L, P < 0.05). However, there was no statistical significance in the levels of 24-h urine potassium between these two groups of mutations. Though recurrent mutations were associated with more severe clinical symptoms, there was no significant difference in laboratory findings compared to other mutations. We did not detect any significant differences in serum magnesium levels, urinary potassium excretion, and blood pressure between the subgroups.

Analysis of clinical and genetic characteristics among all the pedigree members

According to the genotyping and clinical symptoms, pedigree members were divided into three groups: patient (n = 17), carrier (n = 35), and healthy control (n = 34). Laboratory values of all the members according to different genotypic backgrounds were analyzed (Fig. 4). As expected, blood pressure and serum K+ and Mg2+ levels were significantly lower in the patient group than in the carrier and healthy control groups. The carrier group had normal blood pressure, serum K+ and Mg2+ levels, which showed no significant differences compared with the healthy control group (Fig. 4a–d). Moreover, the 24-h urinary Na+ level in the patient group increased significantly (*P < 0.0001, Fig. 4e). It is noteworthy that the 24-h urinary Na+ excretion in the carrier group was also higher than that in the healthy control group (#P < 0.0001, Fig. 4e). Though the 24-h urinary K+ level in patients obviously increased, there was no significant difference between the carrier and healthy control groups (Fig. 4f). Likewise, GS patients exhibited the lowest 24-h urinary Ca2+ level (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4g), while the carrier and healthy control groups presented similar levels of Ca2+ excretion. Consequently, although blood pressure, serum K+ and Mg2+ levels in heterozygous carriers were normal, 24-h urinary Na+ excretion increased significantly. These results suggest a potential role of sodium urine excretion in the early identification of GS.

Clinical and genetic characteristics analysis among all the pedigree members. The mean ± SD values of laboratory parameters are shown for patient, carrier, and health control. P values for ANOVA among different genotype classes are indicated. *P value between patient and carrier, #P value between carrier and health control

Follow-up

During the follow-up, most of the patients took different doses of potassium supplements. As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 5, both serum potassium and magnesium levels improved significantly after treatment (P < 0.0001, P = 0.0004). However, there was no difference in serum potassium and magnesium levels at different periods of treatment.

Serum potassium levels increased from approximately 2.5 mmol/L to above 3 mmol/L. Serum magnesium levels almost returned to the normal range from the original level of 0.5 mmol/L. Though the majority of patients were asymptomatic, only 41.2% reached normal serum potassium levels. Compared to potassium, serum magnesium levels were easier to improve. More than 80% of patients achieved normal magnesium levels after treatment. Interestingly, patients with higher blood potassium levels mainly had higher magnesium intake. It is noteworthy that patients were taking 2–3 medicines with higher doses than usual prescription to keep their potassium steady. Six patients were taking spironolactone simultaneously, but no significant elevation in the serum potassium level was observed. Therefore, hypokalemia in GS patients was difficult to cure, while hypomagnesemia seemed easier to ameliorate.

One patient (pedigree H II-3) still suffered from periodic paralysis, tetany and cramps every 4–5 days, even while taking oral potassium magnesium aspartate (24 tablets/day) and spironolactone (3 tablets/day). He had to receive intravenous supplementation of KCl and MgSO4. One patient (pedigree BII-1) developed impaired fasting glucose (IFG) with fasting blood glucose 6.56 mmol/L, which was regarded as “prediabetes” [10]. Proteinuria occurred in two patients (pedigree CII-1 and II-2) with normal glomerular filtration rates and creatinine levels.

Discussion

In this study, we summarized and analyzed the genotype and phenotype associations of all the members from 13 GS pedigrees. As expected, male patients had more severe hypokalemia and associated neuromuscular symptoms than females. Importantly, we found that the 24-h sodium urine excretion was significantly higher in heterozygous individuals than in healthy controls, though there was no difference in blood pressure levels between them. Continuous 3-year follow-up showed the difficulty of correcting hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia in GS patients, especially the former. Remarkably, we identified two novel SLC12A3 mutations that enriched the mutation database. Our findings may facilitate the understanding of the clinical and genetic characteristics of GS as well as therapeutic strategies for this disease.

Different from previous studies which focused on the genotype and phenotype of GS patients, we performed an innovatively contrastive analysis of the clinical and genetic characteristics of patients, carriers, and healthy controls in GS pedigrees. As expected, GS patients exhibited the lowest blood pressure, serum K+ and Mg2+ levels, and 24-h urinary Ca2+ levels compared with the carriers and healthy controls. It is worth noting that 24-h sodium urine excretion was significantly higher in the carriers than in the healthy controls, though the blood pressure was not different between them. Diet, such as the intake of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ may play an important role in the serum and urine levels of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+, respectively. Salt wasting caused by diminished NCC activity leads to lower blood pressure in GS patients. Although carriers have higher 24-h sodium urine excretion than healthy controls, they do not have lower blood pressure because of self-selected higher Na+ intake. However, carrier children had lower blood pressures than those of the wild-type relatives because young individuals may have a lower likelihood of self-selected salt intake [11]. This suggested that heterozygous individuals may have a potential mild salt-wasting defect and we raised the possibility that the heterozygous state might underlie additional phenotypes.

As we know, the presence of hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia is highly predictive of the clinical diagnosis of GS, but hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia are not always present [12,13,14,15]. In our study, typical hypocalciuria and hypomagnesemia were not found in one and two patients, respectively. The reasons for normocalciuria and normomagnesemia in patients with GS remain obscure. Perhaps chronic severe hypokalemia results in secondary medullary damage and thereby compromises the function of the loop of Henle (LOH), an important site of calcium reabsorption, and induces a high distal delivery of calcium that exceeds the capacity of the DCT and connecting tubule to reabsorb this calcium [14, 16]. Like calcium, almost all filtered Mg2+ is reabsorbed in the LOH. Contracted extracellular fluid might lead to higher initial aldosterone levels in plasma, which could upregulate NCC in the DCT; the Mg2+ reabsorption that depends on the reabsorption of Na+ was also enhanced in DCT [14]. Moreover, some unknown Mg2+ regulators, such as ionic channels belonging to the transient receptor potential channel family, may diminish renal Mg2+ wasting caused by SLC12A3 mutation [17]. This could explain the normal urine calcium and blood magnesium observed in some patients with GS.

Previous research has shown that patients with deep intronic mutations and two mutated alleles probably had the most severe phenotype [8, 18]. In the correlation between phenotype and genotype analysis in this study, we found that patients carrying intronic or nonframeshift mutations had more severe hypokalemia. The reasons for these interesting discoveries remain incompletely understood. Maybe intronic mutations alter the splicing pattern of RNA precursors and result in the deletion of one or more exons in the mature RNA, which induces a greater loss of NCC activity. It seems difficult to explain the correlation between frameshift or nonframeshift mutation and phenotype we observed. Theoretically, the frameshift mutation should have a more severe phenotype and hypokalemia, which is contrary to the phenomenon we observed. Therefore, more patients are needed to further verify this phenomenon. In addition to the genotype’s effect on phenotype, gender differences could also account for phenotype variability. We confirmed that male patients had more severe phenotypes than females since sex hormones can control the density of NCC in the DCT cells, which leads to changes the renal excretion of electrolytes [19]. In addition, estrogens, progesterone, and PRL can increase NCC activity by increasing renal NaCl cotransporter phosphorylation [20].

It is worth noting that 58.8% of patients never reached normal potassium levels, but only 17.6% of patients never reached normal magnesium levels after treatment. Therefore, we hypothesize that hypokalemia is more difficult to correct than hypomagnesemia, which calls for in-depth research in a large population of GS. We noticed difficulty in reaching normal serum potassium and magnesium levels because a large dose of potassium can cause serious side effect, including gastric ulcers, diarrhea, and vomiting with worsening biochemistries. Furthermore, poor adherence and irregular medication may lead to a poor curative effect, which suggests that long-acting preparations, even weekly preparations, may work better. Interestingly, we found that patients with higher blood potassium levels mainly had higher magnesium intake. The insufficient supplementation of magnesium aggravates hypokalemia and renders it refractory to cure by potassium [21]. Therefore, for some patients with a poor effect of potassium supplementation, we can try to increase the dosage of magnesium supplementation. Previous studies reported that spironolactone might be helpful for hypokalemia to some degree, and spironolactone combined with potassium supplements tended to be more effective [22, 23], but we did not find an advantage of spironolactone treatment. During follow-up, one GS patient developed IFG and two patients presented proteinuria. Some studies have observed the correlation between GS and DM, suggesting that long-term hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia may lead to impaired glucose metabolism. Chronic hypokalemia results in decreased insulin secretion by holding back the closure of ATP-sensitive K + channels and L-type Ca2 + channels on the β cell surface [24, 25]. Moreover, hypomagnesemia can impair the insulin signal transduction pathway and consequently reduce the sensitivity of insulin to glucose, followed by insulin resistance [26]. In addition, the secondary hyperreninemia and hyperaldosteronism observed in GS probably cause insulin resistance [27]. However, the incidence of DM is also increasing. Therefore, the relationship between GS and DM still deserves further study. We will enlarge the sample size and extend the follow-up term to further clarify the correlation between them. GS patients are at high risk for CKD; however, the mechanism is indeed complicated and yet not well clarified. Some studies showed that chronic hypokalemia resulted in renal damage through the generation of renal tubule vacuolization, cyst formation, and tubulointerstitial nephritis [8]. However, other studies demonstrated that increasing of circulating renin, angiotensin II, and aldosterone by hypokalemia-independent volume depletion might be a more important factor of renal impairment and fibrosis [28]. Therefore, blood glucose and renal function indicators should be closely followed up in GS patients.

Notably, we identified two novel mutations (p.G212S, p.W939X) that were predicted to be pathogenic by bioinformatic analysis. Amino acid alignment analysis revealed that the glycine at position 212 and the tryptophan at position 939 were highly conserved among species. The visible differences in the whole protein configuration caused by a single base substitution further confirmed the pathogenicity of the novel mutations. All these findings indicated that the two novel SLC12A3 mutations were probably harmful and pathogenic in the GS patients. We found four recurrent mutants in SLC12A3, which would provide significant information for the screening and genetic counseling of GS. Consistent with our study, Shao, Tseng and Liu et al. also considered the missense mutations T60M and D486 N as highly frequent mutations in the Chinese population [8, 23, 29]. Although GS is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, up to 30% of patients have simple heterozygous mutations [30]. We identified only one mutant allele in two patients. There are several possible reasons why we did not discover any mutations in the second allele: (a) existing sequencing methods can only screen exons and their intron–exon boundaries, which are incapable of finding mutations located in gene-regulating sequences such as the 5′-untranslated region and 3′-untranslated region, promoter and enhancer segments, or some harboring deep intronic mutations [16]; (b) it is difficult to identify gene sequence rearrangements involving one or more exons based on single exon analysis [31]; (c) the normal NCC protein is inactivated in some way by mutant proteins, such as kinases 1 and 4 with no lysine [32, 33]; and (d) epigenetic modifications and/or silent polymorphisms could influence the expression of the NCC [34]. In addition, one (approximately 5.8%) patient was determined to carry three SLC12A3 mutations, which was in line with other published reports [23].

There are certain limitations to our study, such as the relatively small number of pedigrees and slightly short follow-up time. Nonetheless, we are still expanding the scale of the pedigrees and extending the follow-up time to perfect our research. Moreover, conclusion on the treatment is mostly based on observational study which may seem slightly unreliable relative to random control trial (RCT) study. However, our research is rigorously designed and followed up regularly with a dedicated person responsible for regular guidance and testing. If possible, we will design a RCT study to confirm the relevant viewpoints in the future.

In conclusion, the phenotypic variability and characteristics of GS as well as therapeutic strategies merit further research to improve the diagnosis and prognosis of this disease. Moreover, our findings suggested that 24-h sodium urine excretion may be a predictor of early NCC dysfunction and SLC12A3 heterozygous individuals may be more susceptible to diuretic-induced hypokalemia.

References

Blanchard A, Bockenhauer D, Bolignano D, Calo LA, Cosyns E, Devuyst O, Ellison DH, Karet Frankl FE, Knoers NV, Konrad M, Lin SH, Vargas-Poussou R (2017) Gitelman syndrome: consensus and guidance from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int 91(1):24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.046

Calo LA, Maiolino G (2015) Mechanistic approach to the pathophysiology of target organ damage in hypertension from studies in a human model with characteristics opposite to hypertension: Bartter’s and Gitelman’s syndromes. J Endocrinol Investig 38(7):711–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-015-0249-z

Hsu YJ, Yang SS, Chu NF, Sytwu HK, Cheng CJ, Lin SH (2009) Heterozygous mutations of the sodium chloride cotransporter in Chinese children: prevalence and association with blood pressure. Nephrol dial transplant 24(4):1170–1175. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfn619

Knoers NV, Levtchenko EN (2008) Gitelman syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 3:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-3-22

Tago N, Kokubo Y, Inamoto N, Naraba H, Tomoike H, Iwai N (2004) A high prevalence of Gitelman’s syndrome mutations in Japanese. Hypertens Res 27(5):327–331

Pagnin E, Ravarotto V, Maiolino G, Naso E, Davis PA, Calo LA (2018) Galphaq/p63RhoGEF interaction in RhoA/Rho kinase signaling: investigation in Gitelman’s syndrome and implications with hypertension. J Endocrinol Investig 41(3):351–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-017-0749-0

Lu Q, Zhang Y, Song C, An Z, Wei S, Huang J, Huang L, Tang L, Tong N (2016) A novel SLC12A3 gene homozygous mutation of Gitelman syndrome in an Asian pedigree and literature review. J Endocrinol Investig 39(3):333–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-015-0371-y

Tseng MH, Yang SS, Hsu YJ, Fang YW, Wu CJ, Tsai JD, Hwang DY, Lin SH (2012) Genotype, phenotype, and follow-up in Taiwanese patients with salt-losing tubulopathy associated with SLC12A3 mutation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97(8):E1478–E1482. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-1707

Cruz DN, Shaer AJ, Bia MJ, Lifton RP, Simon DB, Yale GS, Bartter’s Syndrome Collaborative Study G (2001) Gitelman’s syndrome revisited: an evaluation of symptoms and health-related quality of life. Kidney Int 59(2):710–717. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002710.x

Nichols GA, Hillier TA, Brown JB (2007) Progression from newly acquired impaired fasting glusose to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 30(2):228–233. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc06-1392

Cruz DN, Simon DB, Nelson-Williams C, Farhi A, Finberg K, Burleson L, Gill JR, Lifton RP (2001) Mutations in the Na–Cl cotransporter reduce blood pressure in humans. Hypertension 37(6):1458–1464

Bettinelli A, Bianchetti MG, Girardin E, Caringella A, Cecconi M, Appiani AC, Pavanello L, Gastaldi R, Isimbaldi C, Lama G et al (1992) Use of calcium excretion values to distinguish two forms of primary renal tubular hypokalemic alkalosis: Bartter and Gitelman syndromes. J Pediatr 120(1):38–43

Tosi F, Bianda ND, Truttmann AC, Crosazzo L, Bianchetti MG, Bettinelli A, Ramelli GP (2004) Normal plasma total magnesium in Gitelman syndrome. Am J Med 116(8):573–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.11.030

Lin SH, Cheng NL, Hsu YJ, Halperin ML (2004) Intrafamilial phenotype variability in patients with Gitelman syndrome having the same mutations in their thiazide-sensitive sodium/chloride cotransporter. Am J Kidney Dis 43(2):304–312

Godefroid N, Riveira-Munoz E, Saint-Martin C, Nassogne MC, Dahan K, Devuyst O (2006) A novel splicing mutation in SLC12A3 associated with Gitelman syndrome and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Am J Kidney Dis 48(5):e73–e79. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.005

Lin SH, Shiang JC, Huang CC, Yang SS, Hsu YJ, Cheng CJ (2005) Phenotype and genotype analysis in Chinese patients with Gitelman’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2500–2507. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1905

Voets T, Nilius B, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Droogmans G, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG (2004) TRPM6 forms the Mg2 + influx channel involved in intestinal and renal Mg2 + absorption. J Biol Chem 279(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m311201200

Balavoine AS, Bataille P, Vanhille P, Azar R, Noel C, Asseman P, Soudan B, Wemeau JL, Vantyghem MC (2011) Phenotype-genotype correlation and follow-up in adult patients with hypokalaemia of renal origin suggesting Gitelman syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 165(4):665–673. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje-11-0224

Chen Z, Vaughn DA, Fanestil DD (1994) Influence of gender on renal thiazide diuretic receptor density and response. J Am Soc Nephrol 5(4):1112–1119

Rojas-Vega L, Reyes-Castro LA, Ramirez V, Bautista-Perez R, Rafael C, Castaneda-Bueno M, Meade P, de Los Heros P, Arroyo-Garza I, Bernard V, Binart N, Bobadilla NA, Hadchouel J, Zambrano E, Gamba G (2015) Ovarian hormones and prolactin increase renal NaCl cotransporter phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 308(8):F799–F808. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00447.2014

Huang CL, Kuo E (2007) Mechanism of hypokalemia in magnesium deficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 18(10):2649–2652. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2007070792

Wang F, Shi C, Cui Y, Li C, Tong A (2017) Erratum to: mutation profile and treatment of Gitelman syndrome in Chinese patients. Clin Exp Nephrol 21(6):1139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-017-1389-6

Liu T, Wang C, Lu J, Zhao X, Lang Y, Shao L (2016) Genotype/phenotype analysis in 67 Chinese patients with Gitelman’s syndrome. Am J Nephrol 44(2):159–168. https://doi.org/10.1159/000448694

Sperling MA (2006) ATP-sensitive potassium channels–neonatal diabetes mellitus and beyond. N Engl J Med 355(5):507–510. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejme068142

Shafi T, Appel LJ, Miller ER 3rd, Klag MJ, Parekh RS (2008) Changes in serum potassium mediate thiazide-induced diabetes. Hypertension 52(6):1022–1029. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.108.119438

Song Y, He K, Levitan EB, Manson JE, Liu S (2006) Effects of oral magnesium supplementation on glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized double-blind controlled trials. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc 23(10):1050–1056. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01852.x

Rahimi Z, Moradi M, Nasri H (2014) A systematic review of the role of renin angiotensin aldosterone system genes in diabetes mellitus, diabetic retinopathy and diabetic neuropathy. J Res Med Sci 19(11):1090–1098

Walsh SB, Unwin E, Vargas-Poussou R, Houillier P, Unwin R (2011) Does hypokalaemia cause nephropathy? An observational study of renal function in patients with Bartter or Gitelman syndrome. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians 104(11):939–944. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcr095

Shao L, Lang Y, Wang Y, Gao Y, Zhang W, Niu H, Liu S, Chen N (2012) High-frequency variant p.T60M in NaCl cotransporter and blood pressure variability in Han Chinese. Am J Nephrol 35(6):515–519. https://doi.org/10.1159/000339165

Gamba G (2005) Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol Rev 85(2):423–493. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00011.2004

Nakhoul F, Nakhoul N, Dorman E, Berger L, Skorecki K, Magen D (2012) Gitelman’s syndrome: a pathophysiological and clinical update. Endocrine 41(1):53–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-011-9556-0

Hollenberg NK (2002) Human hypertension caused by mutations in WNK kinases. Curr Hypertens Rep 4(4):267

Yang CL, Angell J, Mitchell R, Ellison DH (2003) WNK kinases regulate thiazide-sensitive Na–Cl cotransport. J Clin Investig 111(7):1039–1045. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci17443

Riveira-Munoz E, Chang Q, Bindels RJ, Devuyst O (2007) Gitelman’s syndrome: towards genotype-phenotype correlations? Pediatr Nephrol 22(3):326–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0321-1

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (No. 81370891 and No. 81670720), special funds for Taishan Scholar Project (No. tsqn20161071).

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (81370891 and 81670720), special funds for Taishan Scholar Project (tsqn20161071).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the individual participant included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, F., Ying, H., Jia, W. et al. Characteristics and Follow-Up of 13 pedigrees with Gitelman syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 42, 653–665 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-018-0966-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-018-0966-1