Abstract

Introduction

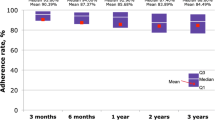

Growth hormone (GH) consumption is the object of a particular attention by regulatory bodies, due to its financial impact; nevertheless, GH treatment has been demonstrated to be cost-effective and is, therefore, usually reimbursed by public health service systems. In Italy, significant differences in GH consumption between regions have been recorded. Different appropriateness in real practice is a possible explanation, but the proportion of drug wasted due to different combinations of therapeutic regimes and types of devices used in drug administration is a complementary explanation. Aim of the study is, therefore, to determine how much of the variability in GH consumption is actually due to differences in clinical practice, and how much to waste.

Materials and methods

A model was settled to estimate the population with indication for GH administration, separately for children, transition subjects and adults, based on both the scientific evidence available and directly collected clinical evaluations. A systematic literature search was conducted using Cochrane Library (HTA and NHSEE) databases, Medline via Ovid, Econlit via Ovid, Embase.

Conclusion

The model applied to the Italian population showed that there was apparently unexplainable over-prescription and potential under-prescription in various regions, ranging from 20 to 40 % less than the estimated theoretical consumption to over 200 %. Wastage, at level of single device, could amount to as much as 15 % of the consumption, demonstrating that price per mg is not in general a good proxy of the cost per mg of therapy. Our estimates of the wastage shows a significant potential gap in the model assessment of the HTA bodies, as far as they do not explicitly take into account the issue of wastage and, consequently, the actual variability in local clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

SHOX has not been included in following analysis because till 2011, in Italy, GH wasn’t authorized for the specific indication.

Adult onset: patients who have growth hormone deficiency, either alone or associated with multiple hormone deficiencies (hypopituitarism), as a result of pituitary disease, hypothalamic disease, surgery, radiation therapy, or trauma; childhood onset: patients who were growth hormone deficient during childhood as a result of congenital, genetic, acquired, or idiopathic causes.

It’s worth noting that since 2006 a biosimilar GH formulation is available (EMEA/H/C/000607).

To date, devices available differ in technical aspects (for example, they may or not have a needle) and in capacity; the amount of device-related waste is consequent to the actual “divisibility” of the capacity to the dosage, as well as to the possibility of using all the GH before it expires. No other potential sources of inefficiency, as malfunctioning, have been considered. More details in [10].

In Italy public reimbursement rely on the predisposition of a therapeutic plan by Regional specialized centres.

Abbreviations

- AIFA:

-

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (Italian Drugs Agency)

- AOGHD:

-

Adult onset growth hormone deficiency

- CRI:

-

Chronic renal insufficiency

- GHD:

-

Growth hormone deficiency

- HAS:

-

Haute Autorité de Santé (French National Health Authority)

- Istat:

-

Italian National Institute of Statistics

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- OSMED:

-

Osservatorio nazionale sull’impiego dei Medicinali

- PWS:

-

Prader–Willi syndrome

- SHOX:

-

Short stature HOmeoboX containing

References

Review of NICE (2010) Human growth hormone (somatropin) for the treatment of growth failure in children NICE technology appraisal guidance, p. 188

Growth Hormone Research Society (2000) Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of growth hormone (GH) deficiency in childhood and adolescence: summary statement of the GH Research Society. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3990–3993

Cook DM, Yuen KC, Biller BM et al (2009) Medical guidelines for clinical practice for growth hormone use in growth hormone-deficient adults and transition patients. Endocr Pract 15 (Suppl 2)

Growth Hormone Research Society (1998) Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adults with growth hormone deficiency. Summary statement of the Growth Hormone Research Society Workshop on adult growth hormone deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:379–381

Li H, Banerjee S, Dunfield L et al (2007) Recombinant human growth hormone for treatment of Turner syndrome: systematic review and economic evaluation [Technology report number 96]. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa

Joshi AV, Munro V, Russell MW (2006) Cost-utility of somatropin (rDNA origin) in the treatment of growth hormone deficiency in children. Curr Med Res Opin 22:351–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1185/030079906X80503

d’Andon A, Barré S, Hamers F et al (2011) L’hormone de la croissance chez l’enfant non déficitaire. In: Evaluation du service rendu à la collectivité. HAS/Service Evaluation des Médicaments et Service Evaluation Economique et Santé Publique

OSMED (vari anni), AIFA-ISS, Roma

Atti a cura di Pricci F, Agazio E. III Convegno Il Treatment con l’ormone somatotropo in Italia; Rapporti ISTISAN 12/24, Istituto Superiore di Sanità 2011, ISSN 1123-3117

Spandonaro F, Mancusi L (2013) Evidenze di efficacia, efficienza e impatto organizzativo per le terapie della GHD. Farmeconomia. Health Economics and Therapeutic Pathways 14(1):7–17

Takeda A, Cooper K, Bird A et al (2010) Recombinant human growth hormone for the treatment of growth disorders in children: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 14:1–209, iii–iv. http://dx.doi.org/10.3310/hta14420

Sybert VP, McCauley E (2004) Turner’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 351(12):1227–1238

Lindgren AC, Ritzén EM (1999) Five years of growth hormone treatment in children with Prader–Willi syndrome. Acta Paediatr Suppl 88(433):109–111

Butler MG (1990) Prader–Willi syndrome: current understanding of cause and diagnosis. Am J Med Genet 35(3):319–332

Molinas C, Cazals L, Diene G et al (2008) French database of children and adolescents with Prader–Willi syndrome. BMC Med Genet 9(89). doi:10.1186/1471-2350-9-89

Karlberg J, Albertsson-Wikland K (1995) Growth in full-term small-for-gestational-age infants: from birth to final height. Pediatr Res 38(5):733–739

Albertsson-Wikland K, Wennergren G, Wennergren M et al (1993) Longitudinal follow-up of growth in children born small for gestational age. Acta Paediatr 82(5):438–443

Ardissino G, Daccò V, Testa S et al (2003) Epidemiology of chronic renal failure in children: data from the ItalKid project. Pediatrics 111(4 Pt 1):382–387

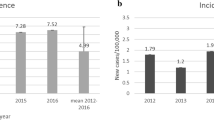

Migliaretti G, Aimaretti G, Borraccino A et al (2006) Incidence and prevalence rate estimation of GH treatment exposure in Piedmont pediatric population in the years 2002–2004: data from the GH Registry. J Endocrinol Invest 29(5):438–442

Cacciari E, Milani S, Balsamo A et al (2006) Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 29 yr). J Endocrinol Invest 29:581–593

Bonfig W, Bechtold S, Bachmann S et al (2008) Reassessment of the optimal growth hormone cut-off level in insulin tolerance testing for growth hormone secretion in patients with childhood-onset growth hormone deficiency during transition to adulthood. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 21:1049–1056

Cook DM, Rose SR (2012) A review of guidelines for use of growth hormone in pediatric and transition patients. Pituitary 15:301–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11102-011-0372-6

Regione Veneto, unpublished data from the Veneto Regional Commission for the prescription of growth hormone

Acknowledgments

This Project was supported by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Italia s.r.l. Pfizer had no role in development of the project, data analysis, preparation of the manuscript, and decisions about submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spandonaro, F., Cappa, M., Castello, R. et al. The impact of real practice inappropriateness and devices’ inefficiency to variability in growth hormone consumption. J Endocrinol Invest 37, 979–990 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0138-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-014-0138-x