Abstract

Objective

This cross-sectional study examined whether religious coping buffered the associations between racial discrimination and several modifiable cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors—systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), body mass index (BMI), and cholesterol—in a sample of African American women and men.

Methods

Participant data were taken from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span study (N = 815; 55.2% women; 30–64 years old). Racial discrimination and religious coping were self-reported. CVD risk factors were clinically assessed.

Results

In sex-stratified hierarchical regression analyses adjusted for age, socioeconomic status, and medication use, findings revealed several significant interactive associations and opposite effects by sex. Among men who experienced racial discrimination, religious coping was negatively related to systolic BP and HbA1c. However, in men reporting no prior discrimination, religious coping was positively related to most risk factors. Among women who had experienced racial discrimination, greater religious coping was associated with higher HbA1c and BMI. The lowest levels of CVD risk were observed among women who seldom used religious coping but experienced discrimination.

Conclusion

Religious coping might mitigate the effects of racial discrimination on CVD risk for African American men but not women. Additional work is needed to understand whether reinforcing these coping strategies only benefits those who have experienced discrimination. It is also possible that religion may not buffer the effects of other psychosocial stressors linked with elevated CVD risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Racial discrimination has been largely implicated in racial health disparities across various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and related risk factors [1, 2, 3, 4]. African American adults carry a disproportionate burden of CVD risk factors like obesity and hypertension and experience earlier onset and greater mortality risk due to CVDs [5, 6, 7, 8]. Equally, compared to all other racial and ethnic groups in the USA, African American adults report more exposure and vulnerability to racial discrimination across commonplace settings [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. Racial discrimination is an established chronic stressor seemingly leading to detrimental health consequences, acting upon multiple psychological, biobehavioral, and physiological pathways (e.g., poorer emotional regulation, greater depressive symptoms, engagement in maladaptive coping strategies, low-grade inflammation, and cardiac reactivity [14, 15, 16].Research has documented associations between experienced racial discrimination and elevated blood pressure (BP), higher body mass index (BMI), and worse cardiometabolic health [17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23]. It remains unclear if these effects are more striking in African American women versus men [24, 25]. Nevertheless, discrimination exerts a cumulative impact on their overall health and well-being and is a fundamental contributor to racial disparities across cardiovascular diseases. Efforts to mitigate these racial health disparities must also identify protective factors that can counteract discrimination’s health impacts.

Markedly, a large body of literature has shown promising associations between frequent religious participation and better cardiovascular health as well as decreased mortality risk among African American adults [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. Compared to other racial and ethnic groups in the USA, African American adults (and women more so than men) exhibit the highest levels of religiosity across multiple indicators of engagement (e.g., religious service attendance, religious coping use, prayer) [33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]. Religion is intimately connected to their fortitude and survival through centuries of longstanding oppression and racial discrimination [39]. Expressly, in the face of relentless racism, the institutional black church has been a cornerstone of support to combat social inequity [39, 40, 41, 42]. Liturgical foci in predominantly black churches regularly integrate racial empowerment, hope, and themes of resilience into sermonic teachings and corporate worship [40, 43, 44]. Fittingly, religious African American adults commonly turn to prayer and church-based social support as coping strategies to deal with racial discrimination, too [45].

Religious coping practices have been shown to yield health benefits, even for those who experience chronic stress and unfair treatment [46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51]. Select coping strategies have been shown to “buffer” (or reduce) the health detriments associated with experiencing chronic stress [52, 53, 54]. It is theorized that coping strategies like prayer and meditation can help inhibit stress-related physiological pathways by diminishing cardiac reactivity as well as inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. Religious people are also less likely to engage in risky lifestyle behaviors (e.g., binge drinking), display fewer depressive symptoms, and repeatedly rely on their church-based social support networks for help, which in turn have positive downstream effects on their overall health [62, 63, 64, 65]. Few studies have explored the potential buffering effects of religious coping on the relationships between discrimination and CVD risk factors, but findings have been inconclusive [66]. Correspondingly, if these potential buffering influences do exist, there are at least two critical reasons why these associations might vary by sex.

First, African American women and men experience and self-report racial discrimination differently. African American women, who live at the interstices of being both black and female, are often invisibilized in the discourse of racism, despite facing mistreatment, sexist and racial epithets, microaggressions at school or on their jobs, discrimination from law enforcement, and numerous other circumstances where they are disrespected or undervalued [13, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74]. However, African American men often self-report more experienced race-based discrimination compared to women [9, 13, 75]. One reason for this might be that stereotypical depictions of black men regularly portray them as threatening and violent, which contributes to more frequent, hostile interactions with law enforcement, colleagues at work, and professionals in academic settings [76, 77, 78]. By and large, though, for men, these experiences with racial discrimination have been frequently linked to heightened CVD risk [79, 80]. In this way, the detrimental effects of these relationships may be exacerbated for African American men because of their salience to race-related discrimination.

Second, with respect to religious participation and associated coping use, there are noticeable sex differences. Women are more religious than men, and they are more likely to turn to their religious communities to make sense of and cope with stressful experiences [35, 65, 81, 82]. However, studies have found mixed results regarding religiosity and CVD risk, with some observing poorer outcomes among religious African American women and men when compared to their less religious counterparts [29, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87]. As African American men are typically less religious than their female counterparts, it is possible that, in the face of racial discrimination, they perceive religious coping as a unique source of comfort. When traumatic life events (racial discrimination, family conflict, unemployment) occur, African American men who turn to religious coping may do so because the situations seem beyond their control, especially because they are far less likely to seek support from friends, health care professionals, or counseling services than women [88, 89, 90]. Consequently, if men turn to religion as a potential stress-buffering resource in the context of racism and discrimination, these moderating effects might be more prominent for them than for women, who, despite their routine religiosity, still turn to religion for comfort but do so irrespective of the type of stress they face [91].

To our knowledge, no study has examined the interactive effects of religious coping on the associations between racial discrimination and CVD risk explicitly among African American men and women. This study used cross-sectional data from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity Across the Life Span (HANDLS) study to address this inquiry. We included several modifiable CVD risk factors (systolic and diastolic BP, BMI, fasting glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and total cholesterol) commonly screened in primary care settings, as prior research tends to rely heavily on BP and hypertensive status [92, 93]. Moreover, we only focused on African American adults, given the sociohistorical and cultural backdrops of racism and black American religion. We seek to provide additional insight into the role of religion as a protective and resilience factor that explains the heterogeneity across health outcomes among African American adults who experience race-related stress. Lastly, several mechanisms through which religious coping use might diminish the biological effects of racial discrimination on CVD risk (better emotional and psychological wellbeing, healthier lifestyle behaviors, an increased social support network, and better stress-physiological regulation) are plausible [46, 49, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99]. Thus, we conducted sensitivity testing to determine if these relationships withstood adjustment for additional psychological, biobehavioral, social, and biomedical covariates. We hypothesized that the lowest levels of CVD risk factors would be observed among African American men who experienced racial discrimination but also frequently used religion to cope. For women, we suspected potential buffering effects would still emerge but would be less striking than for men.

Methods

Sample and Participants

The HANDLS is an ongoing longitudinal cohort study that examines health disparities attributable to race and socioeconomic status (SES). The HANDLS comprises a fixed cohort of 3720 urban-dwelling African American and white adults recruited from 13 neighborhoods in Baltimore City, Maryland. Participants were between the ages of 30 and 64 years old at baseline (wave 1, 2004–2009) [100]. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. All participants provided written informed consent. For this study, participant data were taken from wave 1. Of the African American participants who met study recruitment criteria, we excluded individuals from the current analyses if they had a medical history of HIV/AIDS, were renal dialysis patients, did not fast prior to blood draws, or were missing data on any variables of interest. We used a complete case analysis for this cross-sectional study; missing data were not imputed. The final sample included 815 African American adults.

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Covariates

Sex was defined as the sex assigned at birth (reference: women). SES was a dichotomous composite variable including poverty status, defined as an annual household income above or below 125% of the 2004 Federal poverty level relative to family size, and educational attainment vis-à-vis years in education. Participants considered above the poverty level and with ≥ 12 years of education (i.e., earned at least a high school diploma or GED) were classified as having higher SES. Those who were either below the poverty line or had < 12 years of education, or both, were classified as having lower SES (reference: higher SES; for additional review, see Waldstein et al. [101]). The use of antihypertensives, antidiabetic, or antilipidemic agents was self-reported and recoded into a single dichotomous variable reflecting medication use (reference: no treatment). Participants provided information on their faith tradition and/or denomination with fill-in responses, which were reviewed and reclassified into the following categories: (1) unaffiliated; (2) Christian or Catholic; (3) Islam, (4) Judaism; (5) others (e.g., Buddhism, etc.); and (6) illegible/indecipherable. These were reported for descriptive purposes only.

Outcome Variables

Systolic and diastolic BP were collected using a standard brachial artery auscultation method in the seated position; two measures across a 5-min time interval, one from each arm, were then averaged (mmHg). BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2), with measurements taken via calibrated equipment. Fasting blood tests were drawn to measure serum levels of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and total cholesterol. Cholesterol was derived using a spectrophotometer (mg/dL), and HbA1c (%) was measured by way of liquid chromatography.

Predictor Variable

Racial discrimination was measured using a six-item instrument originally tested and validated in a large, epidemiological cohort study, which was also included in the Experiences of Discrimination Scale [102]. It included the following questions and domains: “Have you ever experienced racial discrimination (1) at school, (2) when getting a job, (3) at work, (4) when getting housing, (5) when getting medical care, and (6) from the police or in judicial courts?” (Cronbach’s α = 0.81). Almost half of the participants reported never experiencing racial discrimination (47.6%). A dichotomous variable was then created to reflect “no prior racial discrimination” (reference) versus “any experienced racial discrimination.”

Moderator Variable

Religious coping use comprised two items taken from the Religion subscale in the Brief COPE Inventory: “When confronted with a difficult or stressful event, I try to (1) find comfort in my religion or spiritual beliefs; and (2) pray or meditate” [103]. Responses ranged from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“a lot”). Higher scores indicated frequent religious coping use. Prior work has found this subscale to demonstrate high internal consistency and the overall inventory’s test–retest reliability to be stable [104, 105, 106]. In our study population, this scale had strong internal consistency among African American adults (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). Religious coping was mean-centered prior to regression analyses.

Sensitivity Variables

Depressive symptoms were characterized using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) [107], which assessed depressive symptoms within the past week. Marital status was classified as either married/partnered versus single (reference). Instrumental and emotional social support coping use as well as substance use coping were also subscales taken from the Brief COPE Inventory [103]. Responses were summed per each dimension, as previously described for the moderator variable, and were standardized prior to analyses (Cronbach’s α = 0.70, 0.64, and 0.83, respectively). Cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use (marijuana, opiates, cocaine) were three separate dichotomous variables reflecting self-reported history of use (“ever used” versus “never used”: reference). Participants also self-reported previous diagnoses of the following CVDs—stroke or transient ischemic attack, coronary artery disease, coronary heart disease, claudication, heart attack/myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, or congestive heart failure. The medical history of prior CVDs was recoded to reflect “no diagnosis” (reference) or “any of these conditions.” Participants also indicated whether they had health insurance (uninsured: reference).

Data Analytic Plan

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software version 4.4.0 [108]. Participant characteristics were described overall and stratified by sex. Student’s t tests and Chi-squared tests (χ2) were used to compare group means for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Histograms and Q–Q plots were used to assess the normality of outcome variable distributions. Logarithmic data transformations were used to resolve skewness for HbA1c and BMI. All tests were two-tailed. A probability value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Hierarchical-entry, sex-stratified linear regression models were used to examine both the main effects and two-way interactive effects of racial discrimination and religious coping with respect to each CVD risk factor (systolic and diastolic BP, HbA1c, BMI, cholesterol) as outcome variables (i.e., parallel analyses were conducted in men and women). All base models controlled for sociodemographic variables (age, SES, medication use). Multicollinearity was assessed for each set of regression analyses. Two successive models were run for each CVD risk factor. In the first step, the main effects of racial discrimination and religious coping as well as sociodemographic covariates were included in the regression model (model 1). In the second step, the two-way interaction term (i.e., racial discrimination × religious coping) was added and assessed for its role in the respective CVD risk factor as the outcome (model 2). If the two-way interaction term was significant, interactive plots were produced and the main effects in model 1 were not interpreted. However, if the two-way interaction term did not reach statistical significance, then the main effects from model 1 were interpreted and retained as the final model.

After interactive plotting, the two-way interaction term was then decomposed using simple slope regressions to determine if the relationship between the frequency of religious coping use and the CVD risk factor varied by way of experienced discrimination (i.e., “any” versus “none”) and if the effect was statistically significant. Sensitivity analyses then assessed if the two-way interactive effect was independent of psychological, biobehavioral, social, and biomedical factors in individually clustered groupings. These included: (1) depressive symptoms; (2) cigarette, alcohol, illicit drug use, and substance use coping; (3) marital status, instrumental and emotional social support coping; and (4) medical history of prior CVDs, and health insurance status. We also conducted sensitivity testing with BMI in models that did not examine it as an outcome variable. We entered each set of clustered sensitivity variables into separate regression analyses to compensate for potentially reduced statistical power.

Results

Sample descriptive characteristics of the final sample (N = 815 African American participants; 55.2% women, mean age = 48.61 years old, 57.7% low SES) can be found in Table 1. Overall, women were over-represented in this study sample (p < 0.001). More than half of all participants (52.3%) reported having previously experienced racial discrimination. More men than women endorsed these experiences. Men were also more likely to be married/partnered, smoke cigarettes, use illicit drugs, drink alcohol, and use substances as a means of coping compared to women. Conversely, women used religious coping more frequently than men as well as emotional social support coping. They were also more likely to have health insurance, currently use medication to manage CVD risk (antihypertensives, antidiabetics, antilipidemic agents), have hypertension, have higher BMI, and have lower DBP compared to men.

Table 2 summarizes the results from the hierarchical-entry linear regressions among the male and female participants in the sample, with systolic and diastolic BP, HbA1c, BMI, and total cholesterol as separate outcomes, racial discrimination and religious coping as predictors, and age, SES, and medication use as covariates. The unstandardized regression coefficients are presented in Table 2 for all primary models that assessed the main effects and two-way interaction terms in sex-stratified analyses.

Sex-Stratified Analyses: Results for African American Men

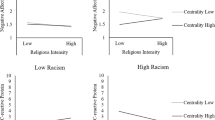

In analyses examining systolic BP as the outcome, in the first step, Model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 359) = 6.64, R2 = 0.072, p < 0.001. However, the addition of the interaction term in the second step explained an additional 1.79% of the variance, F(6, 358) = 6.98, R2 = 0.090, p < 0.001, and was statistically significant (b = 4.39, SE = 1.55, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.02; see Model 2 in Table 2; the Supplemental File contains the full results of all regression models). As shown in Fig. 1, simple regression slopes showed that religious coping use was positively associated with systolic BP among men who reported no prior racial discrimination (b = 3.49, p < 0.01) but was inversely associated with systolic BP among men who experienced racial discrimination (b = − 0.89, p = 0.35) (see Table 3 for full results).

In analyses examining diastolic BP as the outcome, in the first step, model 1 found a main effect of religious coping, F(5, 359) = 3.38, R2 = 0.032, p = 0.005. Greater religious coping was associated with higher levels of diastolic BP (b = 1.68, SE = 0.56, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.02; see model 1 in Table 2). In the second step, the addition of the interaction term explained an additional 1.32% of the variance, F(6, 358) = 3.85, R2 = 0.045, p < 0.001, and was also statistically significant (b = 2.80, SE = 1.15, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.02). Consequently, the significant main effect of religious coping in model 1 was no longer interpreted. As shown in Fig. 1, simple regression slopes showed that religious coping use was positively associated with diastolic BP for all men. However, the magnitude of these relations was smaller among those who reported experiencing racial discrimination (b = 0.59, p = 0.40) compared to men who reported no prior racial discrimination (b = 3.40, p < 0.01) (see Table 3 for full results).

In analyses examining HbA1c as the outcome, in the first step, similar to the findings for systolic BP, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 359) = 15.10, R2 = 0.162, p < 0.001. However, the addition of the interaction term explained an additional 0.90% of the variance, F(6, 358) = 13.53, R2 = 0.171, p < 0.001, and was statistically significant (b = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.03, η2 = 0.01; see model 2 in Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1 and in Table 3, simple regression slopes showed that religious coping use was positively associated with HbA1c among men who reported no prior racial discrimination (b = 0.03, p = 0.01), but was unrelated to HbA1c among men who reported previously experiencing racial discrimination (b = 0.00, p = 0.66).

In analyses examining BMI as the outcome, in the first step, similar to the findings for systolic BP and HbA1c, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 359) = 9.14, R2 = 0.101, p < 0.001, though religious coping was marginally associated with higher BMI (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, p = 0.07, η2 = 0.009). However, in the second step, the addition of the interaction term did not explain any additional variance in the overall model, and it was not significant (b = 0.02, SE = 0.02, p = 0.32, η2 = 0.003; see model 2 in Table 2). No further analyses with BMI as the outcome variable were conducted.

Lastly, in analyses examining total cholesterol as the outcome, in the first step, similar to prior findings, neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, but the overall model was also nonsignificant, F(5, 359) = 0.45, R2 = − 0.008, p = 0.81. In the second step, although the addition of the interaction term explained an additional 1.18% of variance and was statistically significant (b = 11.22, SE = 4.90, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.01), the overall model fit remained nonsignificant, F(6, 358) = 1.26, R2 = 0.004, p = 0.278 (see model 2 in Table 2 and the Supplemental File for full results of the regression models). The interaction term was therefore rendered nonsignificant. Across all regression models for the five separate outcome variables, there were no issues of multicollinearity (VIF < 1.13).

Sensitivity Testing: Results for African American Men

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the significant interactive relationships only (systolic and diastolic BP, HbA1c). All findings remained significant after additional adjustments were made for the following sensitivity variables in clustered groupings: (1) depressive symptoms; (2) cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use, substance use coping; (3) marital status, instrumental and emotional social support coping; and (4) medical history of prior CVDs, health insurance status. When BMI was examined as a sensitivity variable, the two-way interactive effect remained significant for both systolic and diastolic BP but lost significance for HbA1c (p = 0.06). (These results can be found in the Supplemental File.)

Sex-Stratified Analyses: Results for African American Women

In analyses examining systolic BP as the outcome, in the first step, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 445) = 6.64, R2 = 0.177, p < 0.001. When the interaction term was added in the second step, no additional variance was explained, F(6, 444) = 17.01, R2 = 0.176, p < 0.001, and the interaction was not significant (b = − 1.18, SE = 1.69, p = 0.48, η2 = 0.001; see model 2 in Table 2 and the Supplemental File for full results of the regression models).

In analyses examining diastolic BP as the outcome, in the first step, similar to the findings from systolic BP, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 445) = 2.69, R2 = 0.018, p = 0.02. When the interaction term was added in the second step, an additional 0.03% of variance was explained, F(6, 444) = 2.43, R2 = 0.019, p = 0.03, but the interaction was not significant (b = − 1.15, SE = 1.10, p = 0.29, η2 = 0.003; see model 2 in Table 2).

In analyses examining log-HbA1c as the outcome, in the first step, similar to previous findings, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 445) = 13.08, R2 = 0.118, p < 0.001. In the second step, the addition of the interaction term explained an additional 0.80% of the variance, F(6, 444) = 13.53, R2 = 0.171, p < 0.001, and was statistically significant (b = − 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.02, η2 = 0.01; see model 2 in Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1, simple regression slopes showed that religious coping use was negatively associated with log-HbA1c among women who reported no prior racial discrimination (b = − 0.01, p = 0.23) but was positively associated with log-HbA1c among women who reported previously experiencing racial discrimination (b = 0.02, p = 0.06) (see Table 4 for full results).

In analyses examining log-BMI as the outcome, in the first step, similar to previous findings, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use were significant main effects, F(5, 445) = 10.66, R2 = 0.097, p < 0.001. In the second step, the addition of the interaction term explained an additional 0.59% of the variance, F(6, 444) = 9.59, R2 = 0.103, p < 0.001, and was statistically significant (b = − 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.049, η2 = 0.009; see model 2 in Table 2). As shown in Fig. 1 and in Table 4, simple regression slopes showed that religious coping use was negatively associated with log-BMI among women who reported no prior racial discrimination (b = − 0.03, p = 0.12) but was positively associated with log-BMI among women who reported previously experiencing racial discrimination (b = 0.02, p = 0.22).

Finally, in analyses examining total cholesterol as the outcome, in the first step, similar to previous results, model 1 showed neither racial discrimination nor religious coping use was the significant main effect, F(5, 445) = 4.62, R2 = 0.039, p < 0.001. When the interaction term was added in the second step, an additional 0.18% of the variance was explained: F(6, 444) = 3.87, R2 = 0.037, p < 0.001, but the interaction term was not significant (b = 1.48, SE = 3.85, p = 0.70, η2 = 0.003; see model 2 in Table 2). Across all regression models for the five separate outcome variables, there were no issues of multicollinearity (VIF < 1.23).

Sensitivity Testing: Results for African American Women

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted only for the significant associations found in African American women (HbA1c, BMI). Similar to the sensitivity testing done in men, the findings for log-HbA1c as an outcome remained significant after adjustments were made for (1) depressive symptoms; (2) cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use and substance use coping; (3) marital status and instrumental and emotional social support coping; and (4) medical history of prior CVDs and health insurance status. However, when BMI was examined as a sensitivity variable, the interactive effect lost significance (p = 0.05). In models examining log-BMI as the outcome variable, findings withstood adjustment for depressive symptoms and biomedical (medical history of prior CVDs, health insurance status) factors. However, the two-way interaction term lost significance when models adjusted for biobehavioral factors (cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use and substance use coping; p = 0.10) and social support indicators (marital status and instrumental and emotional social support coping p = 0.05). These results can be found in the Supplementary File.

Exploratory Analyses: Combined-Sample Moderation Results

In the overall sample of adults, we reran analyses and tested up to the three-way interactive effect of racial discrimination × religious coping × sex with the five biological measures of CVD risk. There were four significant three-way interactions among (1) systolic BP (b = 5.47, p = 0.02), (2) diastolic BP (b = 4.01, p = 0.01), (3) log-HbA1c (b = 0.08, p = 0.002), and (4) log-BMI (b = 0.07, p = 0.03). These results can be found in the Supplemental File.

Discussion

An emerging body of work has proposed that religious coping acts as a “stress-buffering resource,” wherein the expected health detriments associated with a given stressor (experienced discrimination) are lessened, in part, because of coping behaviors and strategies tied to religion. Less is known about how these moderating effects influence modifiable CVD risk factors for African American adults and if these associations vary by sex. Our cross-sectional study found that among men who experienced racial discrimination, greater religious coping use seemingly diminished the adverse effects associated with racial discrimination on some CVD risk factors (BP, HbA1c). However, men who reported never having experienced discrimination but used religious coping frequently showed elevated levels for most CVD risk factors. These relationships were independent of other sociodemographic characteristics and psychological biobehavioral, social support, and biomedical factors, except BMI. Contrastingly, for women, no buffering effects were found. Rather, higher levels of HbA1c and BMI were observed among those who experienced racial discrimination and endorsed frequent religious coping. These associations, however, lost significance when BMI as well as biobehavioral and social support factors were considered. Our primary findings suggest that frequent engagement in religious coping behaviors may reduce the potentially pernicious effects of race-related stress on poorer cardiovascular health for African American men.

To date, only one prior study has examined the interactive associations of unfair treatment and religious coping use with incident hypertension but found no significant moderating effects [66]. Methodological inconsistencies with this prior study may partially explain their null findings. Namely, their participant data were drawn from a study of white and black (African American and Caribbean) Seventh Day Adventists, and the outcome assessed was incident hypertension rather than BP levels. Here, we only examined these relationships within African American adults, given that their experiences with racial discrimination are much more salient and qualitatively divergent from those of white Americans [9, 109]. Also, the stark racial variations across religiosity and the historical relevance of black-affirming religious spaces in a racially marginalizing society suggested that examining these relationships would be most applicable to the African American community.

Our study found these associations to be sex-specific, in that among those who previously experienced racial discrimination, greater religious coping use demonstrably proved to mitigate poorer cardiovascular health for African American men but not women. Prior studies have pointed to possible sex differences across the interactive relations of psychosocial stress/risk and resiliency factors with cardiovascular and overall health outcomes for African American adults [110, 111, 112]. Yet still, it remains unclear if these associations are more striking for either women or men. Engaging in harmful behavioral health-related coping activities like substance use and other unhelpful active coping styles like John Henryism (beliefs and strategies that one can overcome racism by working harder and longer) have been linked with poorer health outcomes and increased CVD risk for African American men, whereas positive, protective factors like optimism and resilience have proved exclusively advantageous for men, too [113, 114, 115, 116, 117]. Active involvement in faith-based communities and religious teachings in black-affirming churches can heavily influence African American men’s racial socialization, developmental processes, and empowerment. When they have encountered racial discrimination, these positive perceptions of leadership, fathering roles, and masculinity are encouragingly helpful [118, 119]. African American men are often afflicted with more severe and fatal clinical CVDs and comorbid conditions and are less likely to maintain routine visits with their primary healthcare providers or manage CVD risk well [120, 121]. Future research should continue to investigate how the interplay of psychosocial risk-and-resiliency factors for African American men affects their long-term cardiovascular health and their risk for severer progression of CVDs.

When faced with race-related stress, religious African American adults turn to religious coping strategies to make sense of what has happened [45, 122, 123]. Repeated exposure to racial discrimination can result in long-term wear and tear on the body and adverse cardiovascular health outcomes [14, 124, 125]. Religious practices, such as prayer or seeking church-based social support, provide ways to cope with and address stressful situations like discrimination [45]. African American church communities also try to encourage mindfulness-based practices and health-promoting behaviors as a way to combat racial health disparities [126, 127, 128]. Our findings contribute to the nascent literature that the physiological burden of racial discrimination might be lessened for African American men who turn to religion as a coping resource. The explicit mechanisms underlying the relationships between racial discrimination, religion, and CVD risk remain understudied.

Notably, though, two additional peculiarities arose from our findings. In the absence of discrimination, men who endorsed greater religious coping use had higher levels across most CVD risk factors examined (Fig. 1). A couple of explanations could potentially clarify these findings. It is possible that other chronic psychosocial or environmental stressors that were not accounted for in this study are affecting their overall cardiovascular health (e.g., workplace stress; [129]). In like manner, there may be some bidirectionality, wherein men suffering from comorbid conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) turn to religion to cope with their health concerns [87]. Also, religious coping use is highly correlated with other indicators of religious involvement; thus, we presume that these participants might also be religious individuals [82, 130, 131]. Prior reports have noted higher rates of CVD-associated comorbidities (hypertension, obesity, diabetes), and clinical events were observed among more religious African American men and others (frequent church attendees), despite religion being commonly thought of as a protective factor related to optimal health outcomes [83, 87]. African American men who are overly committed and involved in church leadership and community-related activities may have less time and energy for health-promoting lifestyle behaviors or might be less motivated to address health conditions [132]. Additionally, sometimes church-sponsored events feature high-caloric foods, and black pastors may avoid discussing medical issues from the pulpit for fear of stigmatizing people or due to a lack of knowledge, confidence, or awareness of the community’s health needs [133].

In addition, some forms of religious coping (e.g., deferred religious coping) may be ineffective in addressing health issues if they are not partnered with more health-conscious behaviors, such as following physician advice or medication adherence [134]. Existing research notes that African American men may defer both health issues and experiences with racism to a higher power [89]. This could contribute to their under-reporting past experiences of racial discrimination. However, when paired with a high reliance on religious coping, this could lead to elevated CVD risk. Studies have highlighted that religion might have a “dark side,” in that it is not always advantageous for emotional regulation and physical wellbeing. Sometimes, religious people may avoid directly dealing with a stressful situation or a major health concern because they believe their divine power will handle it for them, or their religious coping manifests as excessive worrying, self-imposed blame (i.e., what is happening to them is their fault), or religious fatalism (i.e., what is happening to them is divinely ordained) [86, 135, 136]. The nuances of religious coping and religious involvement as a form of coping within the African American community merit further attention in future research.

At the same time, some studies have also surprisingly found inverse relations with respect to discrimination and health outcomes, wherein African American men who reported no discrimination fared worse with respect to their health [137, 138]. Researchers surmise alternative pathways of discrimination appraisal, suggesting that some African American adults may be under-reporting prior experiences of unfair treatment due to memory suppression [139]. For some African American men, admitting they were treated unfairly because of their race might be hard to express due to other personal characteristics (i.e., pride), cultural sways, or simply because they expect it to happen [90]. To this end, it is also possible that since most religions encourage forgiveness, religious African American men may also suppress these memories and emotions (i.e., forgive and forget) even if the harm committed against them still stings. The health detriments associated with these forms of stress exposure can still manifest regardless. Our findings further reinforce the need for attention to examine how the interplay of these psychosocial determinants affects African American men’s cardiovascular health overall. There are dire implications when determinants are singularly viewed as protective or risk factors.

Similarly, our second peculiar finding was that religious coping did not buffer the associations between racial discrimination and CVD risk factors among African American women. African American women’s use of religious coping to deal with a broad range of personal, health-related, and social stressors has been linked with better emotional and physical wellbeing [29, 51, 111, 123, 140]. Scholars have discussed how religion impacts black women’s self-perceptions, motivations, and coping behaviors [123, 141, 142]. However, these “anchors” can also lead to unique social expectations or self-sacrificing behaviors that blur the lines of coping strategies. The Strong Black Woman Schema, for example, is grounded in endurance through intersectional oppression, often referencing religious ideologies [91]. However, it is still complex. While the Strong Black Woman Schema intimates inner strength and divine hope as resilience, it also pushes for self-determination and perseverance through overcoming adversity, which can be emotionally challenging and physiologically harmful for some women, too [143, 144]. We were unable to distinguish between resilience and positive or negative religious coping sentiments in this study, but these remain thought-provoking questions that require further attention [145].

Furthermore, some interpretations of sacred texts can shape narratives of what it means to suffer and how to endure suffering, especially in the face of social adversity [146]. Despite its renowned legacy of fighting against racial inequality, the institutional black church has also been silent on, or perpetuated, other forms of injustice like sexism [141, 147]. For instance, a national survey report conducted by the Pew Research Center showed that nearly half of black Protestants who attend predominantly black churches heard sermons about racism (47%), whereas less than one-third heard sermons about sexism (31%) [36]. African American women contribute greatly to their religious communities as well as organizational events and related activities, often voluntarily. But by and large, they hold fewer official positions of leadership and power, even though they comprise the majority of most religious congregations [148]. Whereas most literature predominantly included Christian-majority samples, studies exclusively featuring African American Muslim women also demonstrate the centrality of faith and community when confronted with discrimination [41, 149, 150]. The lack of buffering effects in this study was surprising but suggests that either religious coping use is not always beneficial for African American women, despite their consistently higher religious profiles, or there may be concerns about measurement issues. Religious coping measures might not fully capture the intricate interactions and diverse experiences of African American women at church or in their communities. Additionally, by focusing on racial discrimination, our study’s results may be obscured for African American women who experience gendered racism, sexism, and other salient forms of discrimination. Future studies should incorporate discrimination measurements that better attend to intersectional identities and continue to examine variations across these linkages before assessing these associations as equivalent for women and men. Our findings corroborate that the health effects of risk and resilience factors need to be studied in African American women and men separately.

Correspondingly, this study had other limitations that required acknowledgment. First, the analyses were cross-sectional, so we were precluded from determining temporality. Mediation was also not tested, given the nature of the study’s parameters, so it is also unclear if any intermediary variables partially explain these relationships (e.g., BMI, health behaviors, social support indicators). Replica studies are needed to confirm if religious coping use bestows buffering effects over time and why these associations might be sex-specific. Second, discrimination is both multidimensional (e.g., intersectional, sex-based, and race-related) and multilevel (e.g., structural, vicarious, or “second-hand”). It is possible that different dimensions of discrimination may presage deviating biological underpinnings. Future work should assess other levels and aspects of discrimination that contribute to poorer health among African American adults [4, 16, 151, 152]. Coupled with this, our measurement of religious coping use only comprised two items, and we were unable to extrapolate which specific coping styles temper or exacerbate the damaging effects of discrimination on CVD risk for African American adults (e.g., positive versus negative coping, self-directing coping styles, meditation rather than prayer). Future work should explore other dimensions of religious coping as well as religious participation and spirituality to determine which behaviors blunt discrimination’s effects on health outcomes and which are most helpful for African American men and women when confronted with race-related stress and mistreatment.

Conclusion

The current study contributes to the existing literature by examining the potential buffering effects of religious coping use on the relations between racial discrimination and CVD risk among a sample of urban-dwelling, midlife African American women and men. Here, we found that for African American men who experienced prior racial discrimination, higher religious coping use was related to diminished CVD risk, but these anticipated effects were not seen among men in the absence of discrimination nor among women who experienced discrimination. Taken together, it remains exceedingly important to consider the continued relevance of religious coping as a mechanism for ameliorating health disadvantages, especially for African American men, for whom the risk of CVD comorbidities and severer and fatal CVDs remains high. Additional work is warranted to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying how psychosocial determinants like racial discrimination and religion “get under the skin.” Moreover, our study confirms that individual- and community-level interventions must attend to the social conditions and culturally lived experiences of African American women and men uniquely. There is an increased reliance on and interest in partnering with predominantly black faith-based communities to achieve large-scale health promotion efforts. These collaborations are also viable opportunities for researchers to identify helpful coping behaviors to prevent exacerbated poorer health due to racism and racial discrimination. Clinicians and medical practitioners can also use psychosocial history questionnaires to assess individuals’ interpersonal problems, direct them to community-based initiatives and resources, or inspire patients to use their intraindividual strategies to help them cope.

Replication

The HANDLS sample is relatively small and drawn from a vulnerable population residing in specific census tracts in Baltimore City, Maryland, USA. Therefore, maintaining confidentiality—especially in the context of a longitudinal study—is paramount. Participants’ identities are at risk under these conditions. Therefore, interested investigators should consult the HANDLS Website at https://handls.nih.gov-specifically, the instructions for collaborators at https://handls.nih.gov/06Coll-dataDoc.htm. Questions should be directed to Alan Zonderman at zondermana@mail.nih.gov.

References

Javed Z, HaisumMaqsood M, Yahya T, Amin Z, Acquah I, Valero-Elizondo J, et al. Race, racism, and cardiovascular health: Applying a social determinants of health framework to racial/ethnic disparities in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15(1):e007917.

Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901.

Paradies YC. Defining, conceptualizing and characterizing racism in health research. Crit Public Health. 2006;16(2):143–57.

Wyatt SB, Williams DR, Calvin R, Henderson FC, Walker ER, Winters K. Racism and cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325(6):315–31.

Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, Albert MA, Anderson CAM, Bertoni AG, et al. Cardiovascular health in African Americans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e423.

Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: Racial disparities in age-specific mortality among blacks or African Americans — United States, 1999–2015. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444–56.

Howard G, Safford MM, Moy CS, Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Unverzagt FW, et al. Racial differences in the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors in older black and white adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1):83–90.

Sundquist J, Winkleby MA, Pudaric S. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among older black, Mexican-American, and white women and men: An analysis of NHANES III, 1988–1994. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(2):109–16.

Beatty Moody DL, Waldstein SR, Leibel DK, Hoggard LS, Gee GC, Ashe JJ, et al. Race and other sociodemographic categories are differentially linked to multiple dimensions of interpersonal-level discrimination: Implications for intersectional, health research. Liu SY, editor. PLos One. 2021;16(5):e0251174.

Borrell LN, Kiefe CI, Diez-Roux AV, Williams DR, Gordon-Larsen P. Racial discrimination, racial/ethnic segregation, and health behaviors in the CARDIA study. Ethn Health. 2013;18(3):227–43.

Gong F, Xu J, Takeuchi DT. Racial and ethnic differences in perceptions of everyday discrimination. Sociol Race Ethn. 2017;3(4):506–21.

Lewis TT, Van Dyke ME. Discrimination and the health of African Americans: The potential importance of intersectionalities. Current directions in psychological science. 2018;27(3):176–82.

National Public Radio, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Discrimination in America: Experiences and views of African Americans [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.npr.org/assets/img/2017/10/23/discriminationpoll-african-americans.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2023.

Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol. 1999;54(10):805–16.

Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105–25.

Agbonlahor O, DeJarnett N, Hart JL, Bhatnagar A, McLeish AC, Walker KL. Racial/Ethnic discrimination and cardiometabolic diseases: A systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;2:783–807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01561-1.

Cunningham TJ, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Jacobs DR, Seeman TE, Kiefe CI, et al. Changes in waist circumference and body mass index in the US cardia cohort: Fixed-effects associations with self-reported experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination. J Biosoc Sci. 2013;45(2):267–78.

Forde AT, Sims M, Muntner P, Lewis T, Onwuka A, Moore K, et al. Discrimination and hypertension risk among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):715–23.

Forde AT, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Bellamy SL, Diez Roux AV. Perceived discrimination and hypertension risk among participants in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(5):e019541. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.019541.

Gaston SA, Atere-Roberts J, Ward J, Slopen NB, Forde AT, Sandler DP, et al. Experiences with everyday and major forms of racial/ethnic discrimination and type 2 diabetes risk among white, black, and Hispanic/Latina women: Findings from the sister study. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(2):kwab189.

Gavin AR, Woo B, Conway A, Takeuchi D. The association between racial discrimination, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cardiovascular-related conditions among non-Hispanic blacks: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III). J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;9(1):193–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00943-z.

Lewis TT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Lackland DT, Evans DA, Mendes De Leon CF. Perceived discrimination and blood pressure in older African American and white adults. J Gerontol - Ser Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(9):1002–8.

Assari S, Lee DB, Nicklett EJ, MoghaniLankarani M, Piette JD, Aikens JE. Racial Discrimination in health care is associated with worse glycemic control among black men but not black women with type 2 diabetes. Front Public Health. 2017;12(5):235.

McKinnon II, Shah AJ, Lima B, Moazzami K, Young A, Sullivan S, et al. Everyday discrimination and mental stress–induced myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2021;83(5):432–9.

Bell CN, Bowie JV, Thorpe RJ. The interrelationship between hypertension and blood pressure, attendance at religious services, and race/ethnicity. J Relig Health. 2012;51(2):310–22.

Brewer LC, Bowie J, Slusser JP, Scott CG, Cooper LA, Hayes SN, et al. Religiosity/Spirituality and cardiovascular health: The American Heart Association life’s simple 7 in African Americans of the Jackson Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;24:e024974.

Bruce MA, Beech BM, Kermah D, Bailey S, Phillips N, Jones HP, et al. Religious service attendance and mortality among older black men. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273806.

Cozier YC, Yu J, Wise LA, VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA, Argentieri MA, et al. Religious and spiritual coping and risk of incident hypertension in the black women’s health study. Ann Behav Med. 2018;52(12):989–98.

Ferraro KF, Kim S. Health benefits of religion among black and white older adults? Race, religiosity, and C-reactive protein. Soc Sci Med. 2014;120:92–9.

Gillum RF, King DE, Obisesan TO, Koenig HG. Frequency of attendance at religious services and mortality in a U.S. National Cohort. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(2):124–9.

Obisesan T, Livingston I, Trulear HD, Gillum F. Frequency of attendance at religious services, cardiovascular disease, metabolic risk factors and dietary intake in Americans: An age-stratified exploratory analysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(4):435–48.

Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Bullard KM, Jackson JS. Spirituality and subjective religiosity among African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites. J Sci Study Relig. 2008;47(4):725–37.

Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, Lincoln KD. Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean blacks and non-Hispanic whites. J Community Psychol. 2008;36(3):371–86.

Levin JS, Taylor RJ. Gender and age differences in religiosity among black Americans. Gerontologist. 1993;33(1):16–23.

Mohamed B, Cox K, Diamant J, Gecewicz C. Faith among black Americans [Internet]. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. 2021 [cited 2022 Jun 26]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/faith-among-black-americans/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jayakody R, Levin JS. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. J Sci Study Relig. 1996;35(4):403.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Importance of religion and spirituality in the lives of African Americans, Caribbean blacks and non-Hispanic whites. J Negro Educ. 2010;79(3):280–94.

Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The Black church in the African American experience. Duke University Press; 1990.

Cone JH. God of the oppressed. Rev. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books; 1997. p. 257.

Mattis JS, Grayman-Simpson NA. Faith and the sacred in African American life. In: Pargament KI, Exline JJ, Jones JW, editors. APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, theory, and research. American Psychological Association; 2013. p. 547–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/14045-030.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Levin JS. Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Sage; 2004.

Cone JH. The Spirituals and the Blues: An Interpretation. Orbis Books; 1972.

Powery LA. Dem dry bones: preaching, death, and hope. Minneapolis: Fortress Press; 2012. p. 157.

Hayward RD, Krause N. Religion and strategies for coping with racial discrimination among African Americans and Caribbean blacks. Int J Stress Manag. 2015;22(1):70–91.

Bierman A. Does religion buffer the effects of discrimination on mental health ? Differing effects by race. J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45(4):551–65.

Ellison CG, Musick MA, Henderson AK. Balm in gilead: Racism, religious involvement, and psychological distress among African-American adults. J Sci Study Relig. 2008;47(2):291–309.

Ellison CG, DeAngelis RT, Güven M. Does religious involvement mitigate the effects of major discrimination on the mental health of African Americans? Findings from the Nashville stress and health study. Religions. 2017;8(9):195.

Hope MO, Assari S, Cole-Lewis YC, Caldwell CH. Religious social support, discrimination, and psychiatric disorders among black adolescents. Race Soc Probl. 2017;9(2):102–14.

Steffen PR, Hinderliter AL, Blumenthal JA, Sherwood A. Religious coping, ethnicity, and ambulatory blood pressure. Psychosomatic Med. 2001;63(4):523–30.

Vander Weele TJ, Yu J, Cozier YC, Wise L, Argentieri MA, Rosenberg L, et al. Attendance at religious services, prayer, religious coping, and religious/spiritual identity as predictors of all-cause mortality in the black women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(7):515–22.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Maton KI. The stress-buffering role of spiritual support: Cross-sectional and prospective investigations. J Sci Study Relig. 1989;28(3):310.

Benson H. The relaxation response: its subjective and objective historical precedents and physiology. Trends in Neurosciences. 1983;6:281–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(83)90120-0.

Cavanagh L, Obasi EM. The moderating role of coping style on chronic stress exposure and cardiovascular reactivity among African American emerging adults. Prev Sci. 2021;22(3):357–66.

Gall TL, Charbonneau C, Clarke NH, Grant K, Joseph A, Shouldice L. Understanding the nature and role of spirituality in relation to coping and health: A conceptual framework. Can Psychol Can. 2005;46(2):88–104.

Hamilton JB, Moore AD, Johnson KA, Koenig HG. Reading the Bible for guidance, comfort, and strength during stressful life events. Nurs Res. 2013;62(3):178–84.

Harrison MO, Koenig HG, Hays JC, Eme-Akwari AG, Pargament KI. The epidemiology of religious coping: A review of recent literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2001;13(2):86–93.

Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, George LK, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. Attendance at religious services, interleukin-6, and other biological parameters of immune function in older adults. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(3):233–50.

Tobin ET, Slatcher RB. Religious participation predicts diurnal cortisol profiles 10 years later via lower levels of religious struggle. Health Psychol. 2017;25(5):1032–57.

Bowie JV, Parker LJ, Beadle-Holder M, Ezema A, Bruce MA, Thorpe RJ. The influence of religious attendance on smoking among black men. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52(5):581–6.

Gillum F, Obisesan T, Jarrett N. Smokeless tobacco use and religiousness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(1):225–31.

Meyers JL, Brown Q, Grant BF, Hasin D. Religiosity, race/ethnicity, and alcohol use behaviors in the United States. Psychol Med. 2017;47(1):103–14.

Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Hope MO. Church support networks of African Americans: The impact of gender and religious involvement. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(5):1043–63.

Teteh DK, Lee JW, Montgomery SB, Wilson CM. Working together with God: Religious coping, perceived discrimination, and hypertension. J Relig Health. 2019;0123456789:40–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00822-w.

Beal FM. Double Jeopardy: To be black and female. Meridians. 2008;8(2):166–76.

Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989;1989:Article 8.

Kwate NO, Goodman MS. Racism at the intersections: Gender and socioeconomic differences in the experience of racism among African Americans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2015;85(5):397–408.

Cox RJA. The impact of mass incarceration on the lives of African American women. Rev Black Polit Econ. 2012;39(2):203–12.

Erving CL, Williams TR, Frierson W, Derisse M. Gendered racial microaggressions, psychosocial resources, and depressive symptoms among black women attending a historically black university. Soc Ment Health. 2022;11:21568693221115770.

Hogan R, Perrucci CC. Black women: Truly disadvantaged in the transition from employment to retirement income. Soc Sci Res. 2007;36(3):1184–99.

Lewis JA, Mendenhall R, Harwood SA, Browne HM. “Ain’t I a woman?”: Perceived gendered racial microaggressions experienced by black women. Couns Psychol. 2016;44(5):758–80.

Potter L, Zawadzki MJ, Eccleston CP, Cook JE, Snipes SA, Sliwinski MJ, et al. The intersections of race, gender, age, and socioeconomic status: Implications for reporting discrimination and attributions to discrimination. Stigma Health. 2019;4(3):264–81.

Mouzon DM, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Ifatunji MA, Chatters LM. Everyday discrimination typologies among older African Americans: Gender and socioeconomic status. Carr D, editor. J Gerontol Ser B. 2020;75(9):1951–60.

Reeves RV, Nzau S, Smith E. The challenges facing black men – and the case for action [Internet]. Brookings. 2020. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-challenges-facing-black-men-and-the-case-for-action/.

Ray R. “If only he didn’t wear the hoodie...” Selective perception and stereotype maintenance. In: McClure S, Harris C, editors. Getting real about race: Hoodies, mascots, model minorities, and other conversations [Internet]. New York: SAGE Publications; 2015 [cited 2023 Mar 21]. p. 81–93. Available from: https://socy.umd.edu/sites/socy.umd.edu/files/pubs/If%20Only%20He%20Didn%27t%20Wear%20the%20Hoodie.pdf. Accessed 12 Sept 2023.

Perry AM, Harshbarger D, Romer C. Mapping racial inequity amid COVID-19 underscores policy discriminations against black Americans [Internet]. Brookings. 2020 [cited 2022 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/04/16/mapping-racial-inequity-amid-the-spread-of-covid-19/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Lincoln KD, Jacob Arriola KR. Racial discrimination, mood disorders, and cardiovascular disease among black Americans. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(2):104–11.

Sheehy S, Aparicio HJ, Palmer JR, Cozier Y, Lioutas VA, Shulman JG, et al. Perceived interpersonal racism and incident stroke among US black women. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2343203.

Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Race and gender differences in religiosity among older adults: Findings from four national surveys. J Gerontol. 1994;49(3):S137–45.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Brown RK. African American religious participation. Rev Relig Res. 2014;56(4):513–38.

Bentley-Edwards KL, Blackman Carr LT, Paul Robbins A, Conde E, Zaw K, Darity WA. Investigating denominational and church attendance differences in obesity and diabetes in black Christian men and women. J Relig Health. 2020;59(6):3055–70.

Feinstein M, Liu K, Ning H, Fitchett G, Lloyd-Jones DM. Incident obesity and cardiovascular risk factors between young adulthood and middle age by religious involvement: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) Study. Prevent Med. 2013;54(2):117–21.

Godbolt D, Vaghela P, Burdette AM, Hill TD. Religious attendance and body mass: An examination of variations by race and gender. J Relig Health. 2018;57(6):2140–52.

Robbins PA, Scott MJ, Conde E, Daniel Y, Darity WA, Bentley-Edwards KL. Denominational and gender differences in hypertension among African American Christian young adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;8:1132–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00895-4.

Skipper AD. Examining the frequency of religious practices among hypertensive and non-hypertensive black men. J Healthc Sci Humanit. 2022;7(1):41–58.

Thorpe S, Stevens-Watkins D, Thrasher S, Malone N, Dogan JN. Religion, psychiatric symptoms, and gender role conflict among incarcerated Black men. Psychol Men Masculinities. 2023;24(1):76–82.

Skipper AD. The role of religious coping in the marital stability of strong. African American couples: A strengths-focused approach. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College; 2016.

Sullivan JM, Harman M, Sullivan S. Gender differences in African Americans’ reactions to and coping with discrimination: Results from The National Study of American Life. J Community Psychol. 2021;49(7):jcop.22677.

Abrams JA, Maxwell M, Pope M, Belgrave FZ. Carrying the world with the grace of a lady and the grit of a warrior: Deepening our understanding of the “strong black woman” schema. Psychol Women Q. 2014;38(4):503–18.

Brondolo E, Love EE, Pencille M, Schoenthaler A, Ogedegbe G. Racism and hypertension: A review of the empirical evidence and implications for clinical practice. Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(5):518–29.

Lewis TT, Williams DR, Tamene M, Clark CR. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2014;8(1):1–15.

Assari S. Race and ethnicity, religion involvement, church - based social support and subjective health in United States: A case of moderated mediation. Int J Prevent Med. 2013;4(2):208.

Bierman A, Lee Y, Schieman S. Chronic discrimination and sleep problems in late life: Religious involvement as buffer. Res Aging. 2018;40(10):933–55.

Caldwell JT, Takahashi LM. Does attending worship mitigate racial/ethnic discrimination in influencing health behaviors? Results from an analysis of the California Health Interview Survey. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(4):406–13.

Henderson L. Racial discrimination, religion, and the African American drinking paradox. Race Soc Probl. 2017;9(1):79–90.

Lee DB, Peckins MK, Miller AL, Hope MO, Neblett EW, Assari S, et al. Pathways from racial discrimination to cortisol/DHEA imbalance: Protective role of religious involvement. Ethn Health. 2018;10:1–18.

Morton KR, Lee JW, Martin LR. Pathways from religion to health: Mediation by psychosocial and lifestyle mechanisms. Psychol Relig Spiritual. 2017;9(1):106–17.

Evans MK, Lepkowski JM, Powe NR, LaVeist T, Kuczmarski MF, Zonderman AB. Healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span (HANDLS): Overcoming barriers to implementing a longitudinal, epidemiologic, urban study of health, race, and socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(3):267–75.

Waldstein SR, Dore GA, Davatzikos C, Katzel LI, Gullapalli R, Seliger SL, et al. Differential associations of socioeconomic status with global brain volumes and white matter lesions in African American and white adults: The HANDLS SCAN study. Psychosomatic Med. 2017;74(4):1095–102.

Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: Risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–81.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief Cope. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100.

Horning SM, Davis HP, Stirrat M, Cornwell RE. Atheistic, agnostic, and religious older adults on well-being and coping behaviors. J Aging Stud. 2011;25(2):177–88.

Benson PR. Coping, distress, and well-being in mothers of children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2010;4(2):217–28.

Bryant-Davis T, Ullman SE, Tsong Y, Gobin R. Surviving the storm: The role of social support and religious violence against women. Violence Women. 2011;17(12):1601–18.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

_R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2023. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

Banks KH. “Perceived” discrimination as an example of color-blind racial ideology’s influence on psychology. Am Psychol. 2014;69(3):311–3.

Bey GS, Jesdale B, Forrester S, Person SD, Kiefe C. Intersectional effects of racial and gender discrimination on cardiovascular health vary among black and white women and men in the CARDIA study. SSM-population health. 2019;1(8)100446.

DeAngelis R, Upenieks L, Louie P. Religious involvement and allostatic resilience: findings from a community study of black and white Americans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;1:137–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01505-1.

Sims M, Glover LM, Norwood AF, Jordan C, Min YI, Brewer LC, et al. Optimism and cardiovascular health among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Prev Med. 2019;129:105826.

Ayazi M, Johnson KT, Merritt MM, Di Paolo MR, Edwards CL, Koenig HG, et al. Religiosity, education, John Henryism active coping, and cardiovascular responses to anger recall for African American men. J Black Psychol. 2018;44(4):295–321.

Barajas CB, Jones SCT, Milam AJ, Thorpe RJ, Gaskin DJ, LaVeist TA, et al. Coping, discrimination, and physical health conditions among predominantly poor, urban African Americans: Implications for community-level health services. J Community Health. 2019;44(5):954–62.

Felix AS, Nolan TS, Glover LM, Sims M, Addison D, Smith SA, et al. The modifying role of resilience on allostatic load and cardiovascular disease risk in the Jackson Heart Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;10(5):2124–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01392-6.

James SA. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1994;18(2):163–82.

Nguyen AW, Miller D, Bubu OM, Taylor HO, Cobb R, Trammell AR, et al. Discrimination and hypertension among older African Americans and Caribbean blacks: The moderating effects of John Henryism. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(11):2049–59.

Allen Q. ‘Tell your own story’: Manhood, masculinity and racial socialization among black fathers and their sons. Ethn Racial Stud. 2016;39(10):1831–48.

Hammond WP, Mattis JS. Being a man about it: Manhood meaning among African American men. Psychol Men Masculinity. 2005;6(2):114–26.

Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, Rodgers SG. Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by black men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20(11):555–62.

Manuel JI. Racial/Ethnic and gender disparities in health care use and access. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1407–29.

Jacob G, Faber SC, Faber N, Bartlett A, Ouimet AJ, Williams MT. A systematic review of Black people coping with racism: Approaches, analysis, and empowerment. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022;25:17456916221100508.

Lewis-Coles MEL, Constantine MG. Racism-related stress, Africultural coping, and religious problem-solving among African Americans. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2006;12(3):433–43.

Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–33.

Ong AD, Williams DR, Nwizu U, Gruenewald TL. Everyday unfair treatment and multisystem biological dysregulation in African American adults. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2017;23(1):27–35.

Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Bradley-Ewing A, Berman M, Bauer A, Catley D, et al. Identifying health conditions, priorities, and relevant multilevel health promotion intervention strategies in African American churches: A faith community health needs assessment. Eval Program Plann. 2018;67:19–28.

Berkley-Patton J, Bowe Thompson C, Bauer AG, Berman M, Bradley-Ewing A, Goggin K, et al. A multilevel diabetes and CVD risk reduction intervention in African American churches: Project Faith Influencing Transformation (FIT) feasibility and outcomes. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(6):1160–71.

Zapolski TCB, Faidley MT, Beutlich MR. The experience of racism on behavioral health outcomes: The moderating impact of mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2019;10(1):168–78.

Curtis AB, James SA, Raghunathan TE, Alcser KH. Job strain and blood pressure in African Americans: The Pitt County Study. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(8):1297–302.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(4):S238–50.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Joe S. Non-organizational religious participation, subjective religiosity, and spirituality among older African Americans and black Caribbeans. J Relig Health. 2011;50:623–45.

Bentley-Edwards KL, Robbins PA, Blackman Carr LT, Smith IZ, Conde E, Darity WA. Denominational differences in obesity among black Christian adults: Why gender and life stage matter. J Sci Study Relig. 2021;60(3):498–515.

Gross TT, Story CR, Harvey IS, Allsopp M, Whitt-Glover M. “As a community, we need to be more health conscious”: Pastors’ perceptions on the health status of the Black Church and African-American communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(3):570–9.

Cummings JP, Pargament KI. Medicine for the spirit: Religious coping in individuals with medical conditions. Religions. 2010;1(1):28–53.

Buck AC, Williams DR, Musick MA, Sternthal MJ. An examination of the relationship between multiple dimensions of religiosity, blood pressure, and hypertension. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(2):314–22.

Ellison CG, Lee J. Spiritual struggles and psychological distress: Is there a dark side of religion? Soc Indic Res. 2010;98(3):501–17.

Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Adler NE, Syme SL. Do experiences of racial discrimination predict cardiovascular disease among African American Men? The moderating role of internalized negative racial group attitudes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1182–6.

Ferraro KF, Zaborenko CJ. Race, everyday discrimination, and cognitive function in later life. Gumà J editor. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):0292617.

Ryan AM, Gee GC, Laflamme DF. The association between self-reported discrimination, physical health and blood pressure: Findings from African Americans, black immigrants, and Latino immigrants in New Hampshire. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(2):116–32.

Cooper DC, Thayer JF, Waldstein SR. Coping with racism: The impact of prayer on cardiovascular reactivity and post-stress recovery in African American women. Ann Behav Med. 2014;47(2):218–30.

Douglas KB. The Black Christ. Orbis Books; 1994.

Mattis JS. Religion and spirituality in the meaning-making and coping experiences of African American women: A qualitative analysis. Psychol Women Q. 2002;26(4):309–21.

Allen AM, Wang Y, Chae DH, Price MM, Powell W, Steed TC, et al. Racial discrimination, the superwoman schema, and allostatic load: Exploring an integrative stress-coping model among African American women. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1457(1):104–27.

Nelson T, Cardemil EV, Adeoye CT. Rethinking strength: Black women’s perceptions of the “strong black woman” role. Psychol Women Q. 2016;40(4):551–63.

Thomas Z, Banks J, Eaton AA, Ward LM. 25 Years of psychology research on the “strong black woman. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2022;9:e12705. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12705.

Townes EM. A Troubling in My Soul: Womanist Perspectives on Evil and Suffering. Orbis Books; 1993.

Turman EM. Black and Blue: Uncovering the ecclesial cover-up of black women’s bodies through a womanist reimagining of the doctrine of the incarnation. In: Kim GJS, Daggers J, editors. Reimagining with Christian doctrines: Responding to global gender injustices 2014; https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137382986_5

Day K. Unfinished business: Black women, the black church, and the struggle to thrive in America. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books; 2012. p. 180.

Byng MD. Mediating discrimination: Resisting oppression among African-American Muslim women. Soc Probl. 1998;45(4):473–87.

Wyche KF. African American Muslim women: An invisible group. Sex Roles. 2004;51(5):319–28.

Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: A guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;191(4):539–47.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(S2):1374–88.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge our funding sources: the National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program ZIAG000513 (Evans) and the University of Maryland Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30 AG028747 (Waldstein). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the University of Maryland or the National Institute on Aging.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Michele Evans and Alan Zonderman. Data analyses were conducted by Jason Ashe. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jason Ashe, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions