Abstract

Background

The influence of socioeconomic disparities and multidimensional stressors on youth tobacco and marijuana use is recognized; however, the extent of these effects varies among different racial groups. Understanding the racial differences in the factors influencing substance use is crucial for developing tailored interventions aimed at reducing disparities in tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents.

Aims

This study aims to explore the differential effects of socioeconomic disparities and multidimensional stressors on tobacco and marijuana use between Black and White adolescents.

Methods

Utilizing longitudinal data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, this research includes a cohort of pre-youth, monitored from the age of 9–10 years for a period of up to 36 months. We examined the impact of various socioeconomic status (SES) indicators and multidimensional stressors, including trauma, financial stress, racial discrimination, and family stress, alongside baseline average cortical thickness and the subsequent initiation of tobacco and marijuana use over the 36-month follow-up.

Results

Overall, 10,777 participants entered our analysis. This included 8263 White and 2514 Black youth. Our findings indicate significant differences in the pathways from SES indicators through stress types to cortical thickness between Black and White youths. Notably, cortical thickness’s impact on the future initiation of tobacco and marijuana use was present in both groups.

Conclusion

The study suggests that compared to White adolescents, Black adolescents’ substance use and associated cortical thickness are less influenced by stress and SES indicators. This discrepancy may be attributed to the compounded effects of racism, where psychosocial mechanisms might be more diminished for Black youth than White youth. These findings support the theory of Minorities’ Diminished Returns rather than the cumulative disadvantage or double jeopardy hypothesis, highlighting the need for interventions that address the unique challenges faced by Black adolescents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth substance use is not distributed randomly in society and is more common in low socioeconomic status (SES) sections. As such, social epidemiologists have tried to understand this distribution of youth substance use [1]. However, SES does not directly influence substance use, and this effect may be carried through a number of processes and factors. To better understand a more holistic picture of substance use inequalities in society [2], researchers have introduced and tested several models that include an array of biopsychosocial factors [3,4,5]. These biopsychosocial models [6] are comprehensive frameworks that propose a sequence of chains and cascades that carry the effects of social environment to the brain and behavior [7]. They commonly start with SES indicators that reflect social context, and then they continue with the perception of the environment which is commonly measured in terms of stressors, and neurobiological changes—such as variations in cortical thickness—to shed light on their combined influence on substance use behaviors [8]. This holistic approach reveals the intricate interplay among social, environmental, neurobiological, and behavioral factors that drive substance use [9]. It captures the biological, psychological, and social dimensions that shape the experiences of young people [10]. Exploring these interactions provides a nuanced view of the origins of social and economic disparities in substance use, especially with regard to substances like tobacco and marijuana. This insight is crucial for developing more effective prevention and intervention strategies that aim to create a more equitable society [11, 12].

A wide range of SES indicators have emerged as the foundational causes of substance use [13]. Factors such as parental education, employment status, and household and neighborhood income, in addition to race and ethnicity, correlate with youth substance use [14]. These SES indicators make the larger social context in which the youth is living [15]. These SES effects, however, are in part because youth in low SES environments are more likely to experience multidimensional stress exposure, which has implications for neurobiological function [16] and cortical structure [17]. In this view, SES indicators are the most upstream factors that impact more downstream effects such as stressors on substance use [18, 19]. SES indicators are modifiable through policy change, as fairness of society investment on tax policies, educational investments, community development, and poverty prevention can change how SES is distributed across populations [20].

Stressors function as a bridge between SES indicators and neurocognitive changes and associated substance use [21, 22]. However, stress is itself heterogenous and encompass financial strain, family stress, discrimination, and life trauma [23]. Although some are more common than others, many of these stressors impact the risk of substance use [24, 25]. Many youth may turn to tobacco or marijuana to cope with various types of stress [26, 27].

As many cortical structures such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [17] are shown to be involved in substance use, some researchers have used average cortical thickness as a key neurobiological mediator in the intricate web of causation from SES to substance use. Multiple cortical areas are also affected by SES and stress exposure, which explains why the cerebral cortex would have implications for youth substance use [28, 29]. Thus, it is likely that alteration in the average cortical thickness may mirror the cumulative impact of low SES and associated stressors; this may provide an efficient (despite not exclusive or complete) biological market to study biopsychosocial mechanisms that social environment gets under the skin and influences youth substance use [28, 29].

However, a growing literature on minorities’ diminished returns (MDRs) also called marginalization-related diminished returns (MDRs) suggests that the effects of SES on stress [30,31,32,33], effects of SES on brain measures such as the cerebral cortex [34,35,36,37,38,39,40], and effects of SES on substance use may differ by race. In MDRs framework, instead of being a biological marker, race is a proxy of racism and what race does to the individual susceptibility and vulnerability. That is, because of social stratification, segregation, and historical injustice [41,42,43,44,45], SES effects have weaker effects of racialized group [46,47,48], and Black youth who face stress on a daily basis may develop some tolerance and habituation as shown in the resilience and habituation literature [49,50,51,52,53,54]; thus, it is plausible to expect racial variation in the SES-stress-cortex-substance sue path, which is called here the biopsychosocial model of substance use.

Aims

By knitting together social determinants, multidimensional stressors, and changes in brain structure within a unified biopsychosocial model, we enhance our understanding of the complex mechanisms driving substance use. This model not only emphasizes the importance of considering a broad spectrum of factors in substance use research but also highlights the necessity for comprehensive strategies that address the intertwined social, psychological, and biological dimensions of substance use disparities. With a focus on tobacco and marijuana—two prevalent substances among youth—this study delves into the pivotal stages of early adolescence.

Methods

Our research involved a re-examination of data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a comprehensive longitudinal study that explores the development of preadolescent children from diverse racial and economic backgrounds as they transition into adolescence [55]. Detailed methodologies of the ABCD study have been documented extensively elsewhere [55]. The ABCD dataset is distinguished by its longitudinal scope, national reach, and the racial, socioeconomic, and geographical diversity of its sample. Schools served as the primary recruitment venues for the study participants [56]. Our analysis focused on a demographic comprising 6003 non-Latino White and 1562 non-Latino African American preadolescents. Ethical clearance for the ABCD project was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), with assent from all adolescent participants and informed consent from their parents [57].

The variables for this study encompassed race, demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, adversities, and substance use.

Predictor Variables

Socioeconomic Status Indicators

-

Household composition: Reported by parents, the presence of parents in the household was categorized into either single (0) or dual-parent (1) households.

-

Household income: Derived from a 1 to 10 scale based on the ABCD study’s classification, where a higher number indicated greater income over the past 12 months, with intervals spanning from less than US $5000 to over US $200,000. This variable was treated as a continuous measure for analysis.

-

Parental education: Inquiries about the highest level of education attained were measured on a scale from 0 (never attended school/kindergarten only) to 21 (doctoral degree), with higher values indicating greater educational achievement.

-

Neighborhood SES: Median family income by zip code was collected and adjusted by dividing by 5000 to facilitate interpretation of beta coefficients.

Mediator 1

Adversity and Stress

Baseline interviews captured adverse life experiences using a validated Life Events History instrument. The total impact of negative life events during adolescence was quantified on a continuous scale.

Economic-Related Strain

A 7-item scale assessed family financial stress over the past year, with questions ranging from food insecurity to inability to afford medical care. Scores were averaged to create a continuous measure of financial stress.

Racial Stress (Discrimination)

Experiences of discrimination were measured annually using a 7-item scale, with higher scores indicating more frequent perceived discrimination.

Family-Related Stress

The Family Environment Scale assessed family conflict through nine items reflecting negative familial interactions, producing a continuous score where higher values indicated greater conflict [58, 59].

Mediator 2

-

Mean cortical thickness: Using structural MRI, cortical thickness was borrowed from ABCD structural measure file at baseline.

-

Moderator

-

Race: Parent-reported race was classified into African American White, the latter serving as the reference group.

Outcome Variable

Substance Use

The assessment of tobacco and marijuana initiation was conducted every 6 months. In our study, substance use referred to experimental use and initiation rather than regular use. We calculated separate variables for the new onset of marijuana and tobacco use. These variables were then combined to create a latent factor that captured their common variance. Tobacco and marijuana initiation were identified if a full cigarette (more than just a puff) was used during the follow-up period, which lasted up to 36 months post-baseline.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted our data analysis using Stata 18.0. The first step involved providing a descriptive overview of the study variables, segmented by racial categories. Following this, we examined the correlation matrix for all variables, again separated by race. Our next step involved constructing a multigroup structural equation model (SEM) [60,61,62], which delineated groups based on racial identity. This SEM was designed to test our biopsychosocial framework, hypothesizing that socioeconomic status (SES) indicators could predict a latent factor comprising tobacco and marijuana consumption. This prediction was made through the mediation of various stress dimensions (mediator 1) and average cortical thickness (mediator 2). Our SEM, incorporating serial mediations, aimed to trace pathways from SES, as exogenous variables, to stressors, viewed as endogenous variables. Paths were also established from stressors to cortical thickness and directly to substance use as well. The fit of our model was evaluated using standard benchmarks, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the comparative fit index (CFI) [63, 64]. Given our study’s extensive sample size, we opted not to use chi-square significance as an indicator of poor model fit. This approach is commonly accepted in SEM analyses involving large samples, which can result in significant chi-square tests despite an overall good fit. Our detailed multigroup SEM [65] enabled us to identify pathways that were significant for one racial group but not for another, offering nuanced insights into the varied impacts of SES on stressors, cortical thickness, and substance use across different racial groups.

Results

Overall, 10,777 participants entered our analysis. This included 8263 White and 2514 Black youth. Table 1 provides their descriptive data. On average, mean cortical thickness was 2.73 mm (SD = 0.09). Parent education was 16.5 (SD = 2.77) years on average. Mean age at baseline was 9.48 years (SD = 0.51).

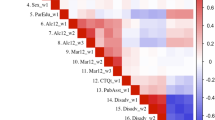

As Table 2 shows, SES indicators, stressors, average cortical thickness, and tobacco and marijuana use showed more correlations in White than Black youth. For White and Black youth, marijuana and tobacco use showed positive correlation with each other. However, tobacco and marijuana showed more correlation with SES indicators and stressors in White than Black youth.

Multivariable Model

As shown in Fig. 1 and Tables 3 and 4, our SEM analysis showed significant pathways from low SES to elevated stress across various realms, subsequently leading to less cortical thickness in White youth. Many of these associations were missing for Black youth. However, for both White and Black youth, a reduction in cortical thickness was correlated with increased youth tobacco and marijuana use. So, stress better mediated the effects of SES on substance use for White than Black youth. This model showed excellent fit: root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.028 (0.024–0.033), comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.959, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.834, Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) = 210,047.129, and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) = 211,336.604.

Discussion

Our findings, based on longitudinal follow-up data of 9–10-year-old children, showed racial variation in the effects of low SES on tobacco and marijuana use through stress and associated changes in average cortical thickness. These mechanisms, from SES to stress and from stress to lower cortical thickness, were more applicable to White youth than to Black youth. While the effect of average cortical thickness on higher substance use was observable in both White and Black youth, the effects of stress and SES were weaker for Black youth compared to White youth. Overall, our biopsychosocial model, which includes the serial mediation of SES and stress, functioned better for White youth than for Black youth.

Although stress in youth is known as a disruptor of homeostasis, and the body’s vital equilibrium [66], stress may have differential implications for Black and White youth. As the brain develops during these formative years, the neurological, cognitive, psychological, and behavioral burden of stress may also vary by race [67]. Racial groups may differ in their appraisals of stress, and their stress response may vary across groups. While low SES and high stress are shown to have psychological impact [68, 69], these effects may vary across diverse populations. This underscores the necessity of understanding tailored programs that may help support the healthy development of diverse groups of youth.

The observation and knowledge that Black youth are more likely to experience perceived discrimination [70] and financial difficulties [71], especially compared to White youth, do not mean that they are also more vulnerable to these stressors. Still, we need anti-discrimination measures [72] and policies that reduce financial stress of all populations [73]. This disparity emphasizes how systemic racism and economic inequalities are deeply intertwined, directly affecting the mental and physical well-being of these individuals [74,75,76,77,78]. By prioritizing efforts to combat discrimination and by implementing policies that promote economic equity—such as targeted financial support, improved access to quality education, and job opportunities—society can address the root causes of these disparities. Such initiatives not only help in alleviating immediate financial pressures but also contribute to creating a more inclusive and equitable environment that supports the healthy development and future success of Black youth. This approach underscores the importance of structural interventions in dismantling the barriers imposed by racial and economic inequalities, highlighting a pathway toward fostering resilience and promoting fairness in the opportunities available to all individuals, regardless of their racial background.

In our study, SES was more of a precursor to stress across domains for White youth compared to Black youth. This finding suggests that variation in SES is a more salient predictor of increased stress in various domains for White children than for Black children. Although Black youth often have lower SES, their SES is less directly connected to their experiences of multidimensional stress. This aligns with previous findings that the effects of SES on stress are weaker for Black than White youth and adults [54]. These racial variations, reflecting weaker protective effects of SES, are consistent with the concept of minorities’ diminished returns, also known as marginalization-related diminished returns [36, 79,80,81,82,83,84]. This supports the intersectionality of SES and race, as proposed by other scholars, and indicates that SES indicators are not comparable across racial groups. These findings contrast with the cumulative disadvantage or double jeopardy theories, which would propose stronger vulnerability to SES for Black youth compared to White youth. Black youth are exposed to stressors such as financial instability, environmental hazards, and poor educational resources across all SES levels. Profound racial injustices in US society have diminished the relevance of high SES on the developmental trajectories of Black children compared to White children, a pattern also observed in health behaviors such as tobacco and marijuana use.

We observed a more salient mediating role of stress on cortical thickness in White youth compared to Black youth. In a previous study, we found that stress has a weaker effect as a predictor of substance use for Black youth than for White youth [85]. This may be because what is frequent may be perceived as normal, making Black individuals potentially less sensitive to stress than White individuals [85]. Black youth may have developed habituation to stress in response to the common nature of such stressors in their communities. Stress may lead to greater changes in brain structure, including cortical thinning, in youth who are less equipped to cope with it. Our observation that stress differentially mediates the relationship between SES and cortical thickness for White youth compared to Black youth supports the higher vulnerability of White youth and the higher resilience of Black youth to socioeconomic and associated adversities [86, 87]. If this is accurate, our traditional measures of stress are more suitable for predicting or explaining neurobiological changes and associated substance use for White youth than for Black youth. In other words, better measures are needed to understand the underlying neurobiological mechanisms of substance use in Black youth.

The mechanism that was similarly observed in Black and White youth was the role of average cortical thickness as a significant predictor of substance use (tobacco and marijuana) in children. This finding indicates that alterations in brain structure can influence the likelihood of engaging in substance use behaviors, regardless of race. It is particularly noteworthy that these relationships were observed in a relatively young cohort, suggesting that the foundations for substance use behaviors are laid down much earlier in life than previously assumed.

Although SES is lower and stress is higher in Black than White children, they have lower rates of tobacco and marijuana use. This presents some degrees of resilience in Black communities and families [88,89,90,91,92]. The weaker effects of SES and stress may be due to stronger community and family bonds, religiosity, cultural norms that discourage substance use, and perhaps a heightened awareness of the legal and social consequences of substance use given the disparities in law enforcement. Additionally, resilience, fostered by collective experiences of overcoming adversity, may equip Black youth with the coping skills to resist peer pressure more effectively. This phenomenon underscores the importance of considering the protective factors that contribute to the health behaviors of minority youth, highlighting the need for nuanced approaches in public health strategies that go beyond the conventional understanding of risk factors [87, 93,94,95].

Racial variation in the linkage from SES to stress and from stress to cortical thickness underscores the importance of race-based tailored programs and interventions. Policies aimed at increasing SES and reducing stressors could play a more salient role in preventing the neurological changes that predispose White children more than Black children to substance use. Furthermore, this study highlights the need for interventions that specifically address stress reduction and coping mechanisms in children from lower SES backgrounds.

This study opens several avenues for future research. Longitudinal studies that track sources of racial variation in developmental trajectories of substance use from youth into adulthood can provide further insights into the long-term effects of early low SES, high stress, and associated cortical changes. Additionally, research exploring the potential reversibility of stress-induced cortical thinning through interventions could offer hopeful prospects for mitigating the risk of substance use. Finally, examining the role of protective factors, such as supportive familial and community environments, could inform the development of comprehensive prevention strategies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings enhance the understanding of racial variation in the multifactorial biopsychosocial pathways that may contribute to substance use among Black and White children. By demonstrating the sequential relationship between SES, stress, cortical thickness, and substance use in White but not Black youth, this study underscores the critical need for tailored interventions that address the root causes of substance use across racialized populations. Such efforts are essential for preventing the neurobiological and behavioral consequences of factors that collectively contribute to inequalities in tobacco and marijuana use across diverse groups. While low SES and high stress play a significant role for White populations, a broader range of factors beyond low SES and high stress may contribute to substance use in Black youth.

Data Availability

The ABCD data are available at the NIH NDA website: https://nda.nih.gov/abcd/.

Code Availability

Codes are available in the appendix.

References

Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:36–52.

Thomas YF. The social epidemiology of drug abuse. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:S141–6.

Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: a test of the social development model. J Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–55.

Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychol Bull. 1995;117:67.

Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: the etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33:995–1026.

Buckner JD, Heimberg RG, Ecker AH, Vinci C. A biopsychosocial model of social anxiety and substance use. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:276–84.

Sales JM, Irwin CE. A biopsychosocial perspective of adolescent health and disease. In: O’Donohue W, Benuto L, Woodward Tolle L, editors. Handbook of adolescent health Psychology. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6633-8_2.

Masiak J. Biopsychosocial model of addictions and other approaches. Polish J Public Health. 2013;123. https://doi.org/10.12923/j.0044-2011/123-4/a.12.

Qu Y, Galván A, Fuligni AJ, Telzer EH. A biopsychosocial approach to examine Mexican American adolescents’ academic achievement and substance use. RSF: Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci. 2018;4:84–97.

Kodjo CM, Klein JD. Prevention and risk of adolescent substance abuse: the role of adolescents, families, and communities. Pediatr Clin. 2002;49:257–68.

Flay BR. Youth tobacco use: Risks, patterns, and control. In: Orleans CT, Slade J, editors. Nicotine Addiction: Principles and Management. New York, NY: Oxford Academic; 1993. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195064414.003.0019. Accessed 10 May 2024.

Fagan AA, Wright EM, Pinchevsky GM. A multi-level analysis of the impact of neighborhood structural and social factors on adolescent substance use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:180–6.

Wu S, Yan S, Marsiglia FF, Perron B. Patterns and social determinants of substance use among Arizona youth: a latent class analysis approach. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110:104769.

Goodman E, Huang B. Socioeconomic status, depressive symptoms, and adolescent substance use. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:448–53.

Cambron C, Kosterman R, Rhew IC, Catalano RF, Guttmannova K, Hawkins JD. Neighborhood structural factors and proximal risk for youth substance use. Prev Sci. 2020;21:508–18.

Gur RE, Moore TM, Rosen AF, et al. Burden of environmental adversity associated with psychopathology, maturation, and brain behavior parameters in youths. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76:966–75.

Boulos PK, Dalwani MS, Tanabe J, et al. Brain cortical thickness differences in adolescent females with substance use disorders. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0152983.

Purtle J, Nelson KL, Henson RM, Horwitz SM, McKay MM, Hoagwood KE. Policy makers’ priorities for addressing youth substance use and factors that influence priorities. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73:388–95.

Matson PA, Ridenour T, Ialongo N, Spoth R, Prado G, Hammond CJ, et al. State of the art in substance use prevention and early intervention: Applications to pediatric primary care settings. Prev Sci. 2022;23(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01299-4.

Dopp AR, Lantz PM. Moving upstream to improve children’s mental health through community and policy change. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2020;47:779–87.

Cornelius J, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Tarter R. Does stress mediate the development of substance use disorders among youth transitioning to young adulthood? Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40:225–9.

Perreira KM, Marchante AN, Schwartz SJ, et al. Stress and resilience: key correlates of mental health and substance use in the Hispanic community health study of Latino youth. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:4–13.

Blumenthal H, Blanchard L, Feldner MT, Babson KA, Leen-Feldner EW, Dixon L. Traumatic event exposure, posttraumatic stress, and substance use among youth: a critical review of the empirical literature. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2008;4:228–54.

Tyler KA, Schmitz RM. Childhood disadvantage, social and psychological stress, and substance use among homeless youth: a life stress framework. Youth Soc. 2020;52:272–87.

Donovan A, Assari S, Grella C, Shaheen M, Richter L, Friedman TC. Neuroendocrine mechanisms in the links between early life stress, affect, and youth substance use: a conceptual model for the study of sex and gender differences. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2024;101121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2024.101121.

Siqueira L, Diab M, Bodian C, Rolnitzky L. The relationship of stress and coping methods to adolescent marijuana use. Subst Abuse. 2001;22:157–66.

Wills TA. Stress and coping in early adolescence: relationships to substance use in urban school samples. Health Psychol. 1986;5(6):503–29. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.5.6.503.

Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiology of the adolescent brain and behavior: implications for substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1189–201.

Chumachenko SY, Sakai JT, Dalwani MS, et al. Brain cortical thickness in male adolescents with serious substance use and conduct problems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41:414–24.

Assari S. Family socioeconomic status and exposure to childhood trauma: racial differences. Children. 2020;7:57.

Assari S, Bazargan M. Unequal associations between educational attainment and occupational stress across racial and ethnic groups. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3539.

Assari S. Parental education and spanking of American children: Blacks’ diminished returns. World J Educ Res. 2020;7:19–44. https://doi.org/10.22158/wjer.v7n3p19.

Assari S. Race, intergenerational social mobility and stressful life events. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018;8. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8100086.

Assari S, Curry TJ. Parental education ain’t enough: a study of race (racism), parental education, and children’s thalamus volume. J Educ Cult Stud. 2021;5:1–21. https://doi.org/10.22158/jecs.v5n1p1.

Assari S, Boyce S, Bazargan M, et al. Parental educational attainment, the superior temporal cortical surface area, and reading ability among American children: a test of marginalization-related diminished returns. Children (Basel). 2021;8. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8050412.

Assari S, Boyce S. Family’s subjective economic status and children’s matrix reasoning: Blacks’ diminished returns. Res Health Sci. 2021;6:1–23. https://doi.org/10.22158/rhs.v6n1p1.

Assari S, Boyce S, Akhlaghipour G, Bazargan M, Caldwell CH. Reward responsiveness in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: African Americans’ diminished returns of parental education. Brain Sci. 2020;10:391.

Assari S. Parental education, household income, and cortical surface area among 9–10 years old children: minorities’ diminished returns. Brain Sci. 2020;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10120956.

Assari S. Age-related decline in children’s reward sensitivity: Blacks’ diminished returns. Res Health Sci. 2020;5:112–28. https://doi.org/10.22158/rhs.v5n3p112.

Assari S. Parental education and youth inhibitory control in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: Blacks’ diminished returns. Brain Sci. 2020;10:312.

Gee GC, Hicken MT. Structural racism: the rules and relations of inequity. Ethn Dis. 2021;31:293.

Gee GC, Hing A, Mohammed S, Tabor DC, Williams DR. Racism and the life course: taking time seriously. Am J Public Health. 2019;109:S43-s47. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304766.

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511.

Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:967–74. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666.

Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, New Directions1. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:115–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000130

Assari S, Sheikhattari P. Racialized influence of parental education on adolescents’ tobacco and marijuana initiation: mediating effects of average cortical thickness. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;3:100107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100107.

Assari S, Najand B, Sheikhattari P. Household income and subsequent youth tobacco initiation: minorities’ diminished returns. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;100063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100063.

Assari S. Minorities’ diminished returns of educational attainment on life satisfaction among Black and Latino adults in the United States. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;100091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100091.

Kim YJ, van Rooij SJH, Ely TD, et al. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder severity and amygdala habituation to fearful stimuli. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:647–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22928.

Stevens JS, Kim YJ, Galatzer-Levy IR, et al. Amygdala reactivity and anterior cingulate habituation predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptom maintenance after acute civilian trauma. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:1023–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.11.015.

Grissom N, Bhatnagar S. Habituation to repeated stress: get used to it. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:215–24.

Cyr NE, Romero LM. Identifying hormonal habituation in field studies of stress. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;161:295–303.

Fernandes-de-Castilho M, Pottinger TG, Volpato GL. Chronic social stress in rainbow trout: does it promote physiological habituation? Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2008;155:141–7.

Assari S, Najand B, Sheikhattari P. What is common becomes normal; Black-White variation in the effects of adversities on subsequent initiation of tobacco and marijuana during transitioning into adolescence. J Mental Health Clin Psychol. 2024;8:33.

Assari S. Parental education and nucleus accumbens response to reward anticipation: minorities’ diminished returns. Adv Soc Sci Cult. 2020;2:132.

Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, et al. Recruiting the ABCD sample: design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004.

Auchter AM, Hernandez Mejia M, Heyser CJ, et al. A description of the ABCD organizational structure and communication framework. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.003.

Boyd CP, Gullone E, Needleman GL, Burt T. The Family Environment Scale: reliability and normative data for an adolescent sample. Fam Process. 1997;36:369–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00369.x.

Assari S, Boyce S, Bazargan M, Caldwell CH. Race, family conflict and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among 9–10-year-old American children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105399.

Cochran JK, Maskaly J, Jones S, Sellers CS. Using structural equations to model Akers’ social learning theory with data on intimate partner violence. Crime Delinq. 2017;63:39–60.

MacKinnon DP, Valente MJ. Mediation from multilevel to structural equation modeling. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;65:198–204. https://doi.org/10.1159/000362505.

Duncan OD. Introduction to structural equation models. London: Academic Press Inc.; 2014.

Lt Hu. Bentler PM: cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55.

Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:424.

Huang PH. A penalized likelihood method for multi-group structural equation modelling. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2018;71:499–522.

Chaplin TM, Niehaus C, Gonçalves SF. Stress reactivity and the developmental psychopathology of adolescent substance use. Neurobiol Stress. 2018;9:133–9.

Romeo RD. The teenage brain: the stress response and the adolescent brain. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:140–5.

Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–30.

Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:343–59.

Jelsma E, Varner F. African American adolescent substance use: the roles of racial discrimination and peer pressure. Addict Behav. 2020;101:106154.

Menasco MA. Family financial stress and adolescent substance use: An examination of structural and psychosocial factors. In: Lee Blair S, editor. Economic stress and the family (Contemporary perspectives in family Research, Vol. 6). Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Leeds; 2012. pp. 285–315. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1530-3535(2012)0000006014.

Solanke I. Making anti-racial discrimination law: A comparative history of social action and anti-racial discrimination law (1st ed.). London: Routledge; 2009. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203875254.

America R. A new rational for income redistribution. Rev Black Political Econ. 1971;2:3–21.

Krieger N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:S20-25. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.98.supplement_1.s20.

Kim HG, Kuendig J, Prasad K, Sexter A. Exposure to racism and other adverse childhood experiences among perinatal women with moderate to severe mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56:867–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00550-6.

Kalbach LM, Aguilar TE. Strategies for incorporating “racism” into a multicultural education foundations course. Multicult Perspect. 2000;2:15–20.

Harnett NG, Ressler KJ. Structural racism as a proximal cause for race-related differences in psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:579–81. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21050486.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Assari S, Najand B, Sheikhattari P. Household income and subsequent youth tobacco initiation: minorities’ diminished returns. J Med Surg Public Health. 2024;2:100063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glmedi.2024.100063.

Bakhtiari E. Diminished returns in Europe: socioeconomic status and ethno-racial health disparities across 30 countries in the European Social Survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:2412–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01178-2.

Assari S, Zare H. Beyond access, proximity to care, and healthcare use: sustained racial disparities in perinatal outcomes due to marginalization-related diminished returns and racism. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;S0882–5963 (0821) 00289-X.

Assari S. Parental education and children’s sleep problems: minorities’ diminished returns. Int J Epidemiol Res. 2021;8:31–9.

Shervin Assari CHC. Mohsen Bazargan: parental educational attainment and Black-White adolescents’ achievement gap: Blacks’ diminished returns. Open J Soc Sci. 2020;8:282–97. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.83026.

Assari S, Zare H, Sonnega A. Racial disparities in occupational distribution among black and white adults with similar educational levels: Analysis of middle-aged and older individuals in the health and retirement study. J Rehabil Ther. 2024;6(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.29245/2767-5122/2024/1.1141.

Binkin N, Spinelli A, Baglio G, Lamberti A. What is common becomes normal: the effect of obesity prevalence on maternal perception. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23:410–6.

Boch SJ, Ford JL. Protective factors to promote health and flourishing in Black youth exposed to parental incarceration. Nurs Res. 2021;70:S63–72.

Keyes CL. The Black-White paradox in health: flourishing in the face of social inequality and discrimination. J Pers. 2009;77:1677–706.

Bowleg L, Huang J, Brooks K, Black A, Burkholder G. Triple jeopardy and beyond: multiple minority stress and resilience among Black lesbians. J Lesbian Stud. 2003;7:87–108.

Rockett IR, Wang S, Stack S, et al. Race/ethnicity and potential suicide misclassification: window on a minority suicide paradox? BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-35.

Rockett IR, Samora JB, Coben JH. The Black-White suicide paradox: possible effects of misclassification. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2165–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.017.

Mouzon DM. Relationships of choice: can friendships or fictive kinships explain the race paradox in mental health? Soc Sci Res. 2014;44:32–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.10.007.

Barnes DM, Bates LM. Do racial patterns in psychological distress shed light on the Black-White depression paradox? A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:913–28.

Willen SS, Williamson AF, Walsh CC, Hyman M, Tootle W. Rethinking flourishing: critical insights and qualitative perspectives from the US Midwest. SSM-mental Health. 2022;2:100057.

Louie P, Upenieks L, Siddiqi A, Williams DR, Takeuchi DT. Race, flourishing, and all-cause mortality in the United States, 1995–2016. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190:1735–43.

Grier-Reed T, Maples A, Houseworth J, Ajayi A. Posttraumatic growth and flourishing in the face of racial trauma. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2023;15:37.

Acknowledgements

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). This is a multisite, longitudinal study designed to recruit more than 10,000 children age 9–10 and follow them over 10 years into early adulthood. The ABCD Study® is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041048, U01DA050989, U01DA051016, U01DA041022, U01DA051018, U01DA051037, U01DA050987, U01DA041174, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041028, U01DA041134, U01DA050988, U01DA051039, U01DA041156, U01DA041025, U01DA041120, U01DA051038, U01DA041148, U01DA041093, U01DA041089, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators.

Funding

Open access funding provided by SCELC, Statewide California Electronic Library Consortium This study is supported by the TRDRP grant fund T32IR5355.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This paper only has one author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Ethical clearance for the ABCD project was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), with assent from all adolescent participants and informed consent from their parents.

Consent to Participate

Youth signed assent. Parents signed consent.

Consent to Publish

NA

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Assari, S. Racial Differences in Biopsychosocial Pathways to Tobacco and Marijuana Use Among Youth. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02035-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02035-8