Abstract

Black and African American adults exhibited higher levels of mistrust and vaccine hesitancy and lower levels of vaccination throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccination and booster uptake remains disproportionately low among Black adults. We conducted a systematic review of empirical research published between February 2021 and July 2022 from five electronic databases and the grey literature. We screened studies that assessed COVID-19 vaccination information needs and preferences as well as communication strategies among Black adults in the USA. We extracted data, then analyzed and synthesized results narratively. Twenty-two articles were included: 2 interventions, 3 experimental surveys, 7 observational surveys, 8 qualitative inquiries, and 2 mixed methods studies. Studies reported credible and preferred COVID-19 vaccination information sources/messengers, channels, and content. Commonly trusted messengers included personal health care providers, social network connections, and church/faith leaders. Electronic outreach (e.g., email, text messages), community events (e.g., forums, canvassing), and social media were popular. Black communities wanted hopeful, fact-based messages that address racism and mistrust; persuasive messages using collective appeals about protecting others may be more influential in changing behavior. Future communication strategies aiming to increase vaccine confidence and encourage COVID-19 booster vaccination among Black communities should be developed in partnership with community leaders and local health care providers to disseminate trauma-informed messages with transparent facts and collective action appeals across multiple in-person and electronic channels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

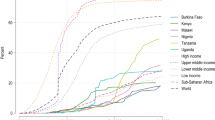

Black or African Americans have been disproportionally impacted by COVID-19 with higher hospitalization and death rates compared to white Americans [1]. COVID-19 outcomes have been exacerbated by low vaccination uptake and comorbidities. Initial vaccination campaigns in April 2021 documented a 14-percentage point gap between Black and White Americans. Although the gap was reduced by July 2022, fewer Black adults had received at least one dose compared to White adults [2]. However, COVID-19 boosters have widened the gap again: 21.2% of Black compared to 32.1% of White adults have received the bivalent COVID-19 booster shot as of December 2022 [3]. Vaccination rates have fluctuated since their authorization and approval, but hesitancy has been pervasive [4, 5]. The determinants of hesitancy vary by communities and socio-cultural factors including race/ethnicity, therefore requiring a nuanced approach to public health campaigns.

In Black communities, vaccine hesitancy and medical mistrust stem from a dark history of unethical medical experiments and persist with racism and mistreatment contributing to health inequities. Structural barriers and communication inequalities left many low-income and low-literate communities with limited access to COVID-19 information which contributed to lower rates of vaccination [6]. Developing a deeper understanding of how to increase vaccine confidence in Black communities through communication strategies is critical to support policy and programs promoting COVID-19 vaccination and may provide helpful insights into future public health campaigns.

There is a growing body of literature exploring attitudes and perspectives of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, information sources, and communication preferences among specific geographic, racial/ethnic, and cultural communities. One narrative review reported on recommendations for vaccine uptake [7]; however, they did not exclusively include empirical data in their review and did not examine strategies and approaches used to promote COVID-19 vaccination. The purpose of this systematic review is to investigate empirical evidence of credible, trusted, and preferred health messengers, messages, and communication channels regarding COVID-19 vaccination among Black adults to inform ongoing and future vaccination and booster interventions with Black communities as the priority audience. Specifically, this review aims to identify the appropriate health messengers to promote vaccine confidence and message content that address vaccine hesitancy among Black communities in the USA, and which communication channels they prefer.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review to analyze findings from empirical studies in peer-reviewed and grey literature. We focused on studies that collected and analyzed quantitative and/or qualitative data from Black adults in the USA on topics including communication strategies and information needs related to COVID-19 vaccination. Literature searches occurred between June and August 2022 to assess literature written and published 6–8 months after the COVID-19 vaccine first became available in December 2021. This review included articles published between February 2021 and July 2022.

Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, World of Science, CINAHL, Academic Search Premier, and ProQuest Social Science Database. Key terms were identified and applied in the same methodical pattern within each search engine. The first and second term in each search string was “COVID-19 vaccine OR COVID-19 Vaccination” and “African American OR American black OR Black,” respectively. The third search term alternated among “Health Information,” “Health Message,” “Trusted Sources,” “Social Networks,” “Information Sources,” “Persuasive Communication,” and “Community-based” in each database. Note that the use of the terms “African Americans,” “Blacks,” “American blacks,” and “Black Americans” varied among the articles.

Eligibility Criteria

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [8]; the review protocol was not registered. The inclusion criteria for this review required that the studies report on interpersonal or organizational information sources and communication strategy preferences (e.g., message content, framing, channels) among Black adults in the USA. We included English-language studies that enrolled solely Black participants, reported 10% of the full sample identified as Black, African American, or Black immigrant, or reported results by race/ethnicity groups. Empirical research that explored COVID-19 vaccination beliefs or behaviors or tested communication strategies were included. Studies were excluded if they focused on participants with underlying health conditions, were based in a hospital or institution, were published prior to 2021 when the vaccine became first became available, or took place in or analyzed data from countries outside of the USA. We did not include conference abstracts, commentaries, editorials, scoping, or systematic reviews.

Study Selection

After duplicates were removed, search results were exported into EndNote for title/abstract and full-text screening. A manual review of relevant excluded literature reviews and commentaries identified two additional studies. Articles were included by agreement with both authors after full-text screening using the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were discussed and resolved to ensure they represented this review’s criteria. The quality of the studies and appropriateness of the methods and techniques (e.g., design, sampling, data collection, analytic methods, stakeholder considerations) were assessed according to the Quality Appraisal for Diverse Studies (QuADS) tool, which allows for assessments of multiple and mixed methods research study designs [9]. Criteria were agreed upon, applied, compared, and discussed by the authors.

Analysis and Reporting

Data were extracted from each study and analyzed using a narrative/evidence synthesis. A meta-analysis was not feasible due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes. We extracted and described study characteristics and grouped them by geographic location and sub-populations. We extracted behaviors, intentions, communication outcomes, or inputs that were significant in quantitative studies and described aspects of the communication process: source/messenger (credibility or trustworthiness), channels (modality), and message (style or content) and thematically analyzed results from qualitative studies. When possible, we used the original study’s language to differentiate between populations (e.g., non-Hispanic Black, Black Latinx, African Americans, African immigrants), but due to varying means of collecting and reporting ethno-racial identity, we generally describe the results in terms of Black individuals or communities.

Results

Search Outcomes

A total of 859 papers were identified and after removing duplicates, 779 were retained for title/abstract screening. Seventy-eight articles underwent full-text screening, and 56 were excluded from the analysis after critical full-text review as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twenty-two were deemed eligible and data, were abstracted independently by both study authors. After reviewing QuADs scores (Supplementary Table), we retained all studies despite some lower scoring criterion (e.g., experiments and surveys scored low on stakeholder considerations) as there is no threshold score for high or low quality [9]. Details of the screening process and reasons for exclusion are reported in Fig. 1.

Study Characteristics

Twenty-two studies analyzing trusted message sources, health messages, and/or communication channels for COVID-19 vaccination were included in this review (Table 1). The types of studies included two intervention trial or implementation evaluations (non-randomized study of intervention) [10, 11], three experimental surveys [12,13,14], seven observational surveys [15,16,17,18,19,20,21], eight qualitative methods (i.e., interviews or focus groups) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], and two mixed methods studies [30, 31]. Five studies enrolled non-Hispanic Black or African American participants exclusively [14, 15, 18, 24, 28] with the remaining studies’ sample compositions of Black participants ranging from 12 to 95%. We identified multiple sub-populations including older adults aged ≥ 65 years, young adults aged 18–30 years, safety-net patients, pediatric patients and families, pregnant/postpartum women, barbershop owners and workers, and people affiliated with faith-based organizations. Nine study settings were specific cities or metro areas (i.e., Boston, Cincinnati, Denver, New Haven, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Shreveport, Washington, D.C.); three were across states or regions (i.e., California, central Missouri, Kansas); ten recruited across the entire USA.

Health Messengers

Most (18) studies reported on health messengers and/or information sources. We identified nine key categories of interpersonal and organizational messengers that were commonly relied upon, considered credible, or described as trustworthy (Table 2).

Personal physicians were mentioned in more studies than any other type of messenger and physician consultations or recommendations were associated with vaccination [10, 11, 16, 17, 19,20,21, 23, 24, 26,27,28, 30]. Other health care professionals and professional associations, including nurses, pharmacists, and community health clinic staff, were also mentioned as trustworthy messengers in multiple studies [16, 21,22,23, 30]. A few studies found that Black health care providers, scientists, and researchers enhanced trustworthiness [24, 27, 30] and may increase acceptance of vaccination [20]. However, one experimental survey found messages from experts with ethno-racial identity concordant to the receiver had no effect on vaccine intentions [13]. Another survey emphasized pregnant/postpartum women would be reassured if they knew their recommending provider was vaccinated [21] and recommendations from pediatricians were sometimes cited as influential in decision-making among family members of pediatric patients [10].

People in social networks including friends, family members, neighbors, and peers were the second most reported messenger across all studies [10, 16, 18, 22, 25, 27, 28, 30, 31]. Notably, input from family members was a common reason for acceptance [10]. Social/family vaccination norms and interpersonal communication were linked with positive vaccination intentions [15, 18] partly by facilitating a return to in-person activities [28].

Church and faith leaders were the third most common messengers reported across studies [16, 22, 23, 25, 28,29,30]. Ministers, faith groups, and other leaders at houses of worship were important COVID-19 information messengers across multiple groups with different ethno-racial identities, but they were particularly emphasized as trustworthy among African Americans and African immigrants. Similarly, community leaders and other community-based organizations (CBOs) [22, 23, 25, 27, 30] were also trusted. Trusted CBOs were often linked with providing access to the vaccine, typically at well-known locations including community clinics, centers, churches, or schools.

Findings about the influence of celebrities and public figures were mixed. Two studies reported that promoting celebrities or famous politicians modeling vaccination was not persuasive [26, 28], but participants relied on some public figures and experts (e.g., Dr. Anthony Fauci) for vaccination information. Still, two others noted African American participants would like to see celebrities [24] and government officials get vaccinated [29]. One survey found African American adults’ willingness to get vaccinated was more likely to increase with endorsements from celebrities than adults of other ethno-racial identities [20]. However, multiple studies reported representation of community members or public figures in vaccine messaging was important to participants with different ethno-racial identities (e.g., Hispanic/Latinx, Chinese American) [22, 23, 27, 30].

A few studies noted that Black adults were more likely than non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latinx adults to consider federal agencies (i.e., CDC, FDA), local or state governments (e.g., departments of health) [16, 28, 29] and/or public health officials [19, 31] credible or trustworthy information sources. However, more studies reported on mistrust of government as described below.

Communication Channels

Two studies evaluated vaccination outcomes in practices or health care systems after interventions. Burkhardt and colleagues reported over 70% of eligible pediatric patients and household members completed two doses after in-person counseling/recommendations from a pediatric provider [10]; however, Black household members were less likely to vaccinate compared to White individuals. Lieu and colleagues found that electronic messages and follow-up postcards from patients’ primary care providers increased vaccination among older adults compared to usual care (no outreach), but they did not evaluate differences by outreach attempts or channel [11].

Nine other studies reported on perspectives about commonly used communication channels and/or future preferences for how African American individuals would like to learn about COVID-19 vaccination. We identified seven categories from the findings (Table 3). Electronic outreach, usually in the form of emails, text messages, and health portal messages, was commonly valued, with one study reporting about African Americans’ reliance on neighborhood/community listservs and newsletters [31]. Online and in-person community events or forums were suggested [21, 24] in addition to door-to-door canvassing as ways to help increase access to information [27, 30] and give opportunities to ask questions. Telephone hotline numbers or chatbots were also strongly desired because of the real-time, interactive nature of getting answers to questions immediately [29, 30]. Face-to-face and telephone conversations with a health care provider were specifically important among individuals with low intentions and pregnant and postpartum women [17, 21].

Although many of these channels were generally suggested as acceptable by the larger Black community, we found some differences by sample sub-populations. Print materials, such as flyers and pamphlets, were suggested specifically for older adults [17, 30]. Traditional media was suggested for widespread reach [25, 30], but some studies indicated these were less trustworthy channels [16] and multimedia platforms were important [27]. Social media was also recommended, though mainly to reach younger adults [21, 24, 27, 30].

Message Features

Three studies evaluated different aspects of messages (e.g., content, style, and framing) using a randomized trial [11] or experimental survey [12, 14]. The study populations were predominately non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and/or Asian Americans; however, the outcomes (e.g., vaccination intention, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccination) and the control/usual care intervention varied. We report the findings among non-Hispanic Black participants. Dhanani and Franz found that messages acknowledging past medical harm and current mistreatment precautions were linked to lower vaccine hesitancy among Black participants [12]. Huang and Green found that self-persuasion narratives elicited greater vaccination intentions among African Americans compared to a plain narrative and a self-persuasion task, particularly among participants with low trust in science [14]. Lieu and colleagues found that standard vaccination messages and culturally tailored messages addressing cost and access barriers both increased vaccination among older Black adults [11].

Multiple survey and qualitative studies reported on preferred message types and communication styles including highly valued COVID-19 vaccination information/content and framing. Half of the studies described safety concerns about the new vaccines and development timeline, so not surprisingly they largely described African American participants wanting to wait and see more data [26, 29]. Detailed content about the development process and safety results were desired [20, 28], especially about Black/African American trial participants, pregnant people [21], and individuals with pre-existing conditions [25]. Generally, studies indicated that content should be based on facts and evidence with transparent and honest messaging. Including clinical trial findings about immediate and potential long-term side effects was important to address safety concerns [22, 24, 27,28,29].

Positive, motivational, and hopeful messages resonated more than fear-based appeals [23, 25, 29, 30]. A few studies also noted framing vaccination as a choice instead of an obligation or mandate would be more effective [22, 30] and may promote more control and freedom to resume social and work activities, which was highly valued among African American participants [23, 24, 28, 29]. Persuasive messages were notably community-focused or appealed to collective action: participants in two studies responded positively to messages about protecting family members, especially children and the elderly, as well as the “social other” because they elicited a sense of unity [23, 29].

Mistrust or low levels of trust in government, health care systems, pharmaceutical companies, and vaccines in general were reported in thirteen studies [15, 16, 19, 20, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. While some surveys found associations between mistrust, low confidence, high hesitancy, and low intentions, many qualitative studies explored reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The findings were mixed regarding how historical racism and mistreatment should be acknowledged; however, most described that messages addressing mistrust and systemic injustices were needed, wanted, and may help build trust among African Americans [23,24,25, 27, 30].

Discussion

This review of 22 empirical studies on COVID-19 vaccination communication strategies summarized trusted messengers, preferred communication channels, and important message characteristics identified by Black and African American adults. The most trustworthy messengers across the studies we reviewed were personal connections or those with shared community and/or identity: personal physicians/primary care providers, social network contacts, and church/faith leaders. Communication channels differed somewhat by audience segments, mainly age-specific preferences. Safety concerns and mistrust influenced hesitancy, so transparent messages with facts that recognize past and current experiences of the Black community were desired.

We found that trusted messengers were individuals who had longstanding, personal relationships with community members. Similar to the uptake of other vaccines [32, 33], a primary care physician or personal health care provider was the most commonly identified trusted messenger for COVID-19 vaccination across the studies we reviewed. These findings demonstrate the importance of including primary care providers in vaccination outreach and education and additional resources for providers to address misinformation and concerns during counseling conversations [34, 35]. Although the influence of a physician recommendation on vaccination is consistent across other ethno-racial identity groups and other vaccines [36,37,38], some studies emphasized that Black health care providers, researchers, and scientists may increase acceptance among Black community members. Indeed, others have suggested that Black pharmacists promoting and administering the COVID-19 vaccine may be important to help expand access and foster trust in Black communities [39]. Therefore, communication strategies should ensure Black health care providers, ideally from the local area, are messengers of COVID-19 vaccination information as representation may increase vaccine confidence in the Black community.

Continuing with the finding that trusted messengers are often personal connections or someone embedded in the local community, contacts within social networks, faith and community leaders, and local and state government officials were also trusted. In some studies, information from and vaccination modeling by these messengers were associated with positive vaccine intentions. This finding is similar to those of other vaccines (e.g., HPV, flu) where community-based organizations and social peers are trusted and can influence uptake [40, 41]. For example, social norms and family culture were particularly influential on flu vaccination among African American adults [38]. Because of strong social ties and network connections, locally driven vaccination campaigns in Black communities should engage trusted leaders with shared identities of the community, including pastors and health officials, to help plan, implement, and disseminate normative messages about vaccination [42]. Social network campaigns or interventions that encourage friends and family to share the benefits of vaccination may accelerate vaccination behavior change by reaching people in their own communities [43, 44].

Preferences for communication channels ranged from digital and traditional media to direct communication in person or over the phone. Though electronic outreach was common, printed materials were preferred among older adults. Social media, though acceptable for the general population, was particularly suggested for reaching younger generations, which is consistent with promotion efforts for other vaccines [45, 46]. A desire for communicating through trusted community channels was reflected in preferences for outreach events and meetings, Q&A sessions, and community canvassing. Indeed, community-based communication to promote COVID-19 vaccination through CBO-sponsored events like virtual town halls and in-person tabling at community fairs has been useful in reaching groups with other ethno-racial identities [47,48,49,50]. Speaking directly with a primary care provider—both face-to-face and over the phone conversations—was another important mode of communication. Direct conversations may be key opportunities to establish trustworthiness, acknowledge historical and current harmful experiences, and build trust among hesitant African American patients [51,52,53]. Recognizing the diversity of Black communities across the USA, these findings highlight the importance of partnering with CBOs to deploy a multimodal approach using different communication channels appropriate for reaching various subgroups.

The preferred message content and style focused on clear, fact-based, and honest messages that address immediate side effects and long-term health impacts of the vaccine. This was not surprising given the high prevalence of vaccine hesitancy [54]. Positive, hopeful, and collective (vs. individual) appeal messages were valued, which may elicit a sense of community and responsibility to protect others [42]. The findings suggest messaging about returning to normal/pre-pandemic activities resonated with African American participants and may have motivated vaccination. However, with substantial social distancing recommendations and policies no longer in place, collective appeals or other- (vs. self-) referencing messages that draw on vaccine confidence, benefits, and hope may be important for promoting boosters, especially for those with low perceived risk [55] or who have been frustrated and annoyed about limited immunity and the need for additional boosters [56]. The results show that strong vaccine efficacy and statistical evidence were also helpful to increase hope and initial vaccination intentions, though persuasive messaging about the continued risk of COVID with loss-frames or fear-based appeals about the disease may influence attitudes and promote booster intentions [48, 57, 58].

Mistrust in the vaccine, health care entities, and governmental bodies was common across many studies. Historically, mistrust has also influenced flu vaccination beliefs and behaviors among African Americans [38] and lends itself to longer vaccination deliberation [53]. A trauma-informed strategy acknowledging historical medical mistreatment and structural racism while emphasizing safety and transparency would help align COVID communication with community needs, values, and strengths [59]. Others have emphasized the importance of developing culturally appropriate messages through audience segmentation, listening circles, and community partnerships to co-create communication strategies that will be highly acceptable among African Americans [52, 60,61,62,63]. Taking a tailored approach based on audience insights and information needs [64] would also foster collaboration and empower Black communities, both key aspects of trauma-informed care [65], to help identify who should spread information and how to best reach the population with messages that resonate [66, 67].

The nature of vaccine hesitancy is context specific [68, 69]; therefore, this review has some limitations. The credibility and trustworthiness of messengers and information sources were not consistently reported across studies, making them difficult to compare. Despite our focus on African American adults in the USA, we included studies with participants of other ethno-racial identities and were limited to the authors’ reports by identity groups. Finally, the studies focused on the initial roll-out of COVID-19 vaccination, which was likely heavily influenced by the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic and rapid vaccine development; booster vaccination is markedly lower [3] and may require additional segmenting and tailored messaging. For example, although some commonalities regarding sub-populations and geographic locations were discussed, future research should investigate differences by geographic locations and additional subgroups within the Black community, including by vaccination status or hesitancy [70]. However, the insights from this review can inform efforts to encourage initial vaccination, booster vaccination for emerging variants, or other novel vaccines.

The communication strategies identified through this review highlight the importance of partnerships between public health and community-based organizations. Collaborating with Black health care providers and local community leaders who are known and trusted by the target community members on a multimodal communication strategy that uses trauma-informed, fact-based messages with a collective action appeal will be important to address hesitancy and promote vaccine confidence among Black communities.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, COVID Data Tracker. US Department of Health and Human Services. CDC: Atlanta, GA; 2023.

Kaiser Family Foundation, KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. 2023.

Lu PJ, Zhou T, Santibanez TA, et al. COVID-19 bivalent booster vaccination coverage and intent to receive booster vaccination among adolescents and adults — United States, November–December 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:190–8. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7207a5.

Njoku A, Joseph M, Felix R. Changing the narrative: structural barriers and racial and ethnic inequities in COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189904.

Gerretsen P, et al. Vaccine hesitancy is a barrier to achieving equitable herd immunity among racial minorities. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:668299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.668299.

Okoro O, et al. Exploring the scope and dimensions of vaccine hesitancy and resistance to enhance COVID-19 vaccination in black communities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:2117–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01150-0.

Dada D, et al. Strategies that promote equity in COVID-19 vaccine uptake for Black communities: a review. J Urban Health. 2022;99(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00594-3.

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Harrison R, et al. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y.

Burkhardt MC, et al. Increasing Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine uptake in pediatric primary care by offering vaccine to household members. J Pediatr. 2022;245:150–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.04.023.

Lieu TA, et al. Effect of electronic and mail outreach from primary care physicians for COVID-19 vaccination of Black and Latino older adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2217004. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.17004.

Dhanani LY, Franz B. An experimental study of the effects of messaging strategies on vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among Black Americans. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101792.

Gadarian SK, et al. Information from same-race/ethnicity experts online does not increase vaccine interest or intention to vaccinate. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):492–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12561.

Huang Y, Green MC. Reducing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among African Americans: the effects of narratives, character’s self-persuasion, and trust in science. J Behav Med. 2022;46(1–2):290–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-022-00303-8.

Bogart LM, et al. COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in a national sample of Black Americans. J National Med Assoc. 2022;113(6):599–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.011.

Davis TC, et al. COVID-19 concerns, vaccine acceptance and trusted sources of information among patients cared for in a safety-net health system. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:6. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10060928.

Fisher KA, et al. Preferences for COVID-19 vaccination information and location: associations with vaccine hesitancy, race and ethnicity. Vaccine. 2021;39(45):6591–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.058.

Francis DB, Mason N, Occa A. Young African Americans’ communication with family members about COVID-19: impact on vaccination intention and implications for health communication interventions. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(4):1550–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01094-5.

Karpman M, et al. Confronting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among nonelderly adults. Urban Institute. 2021;1–21.

Kricorian K, Turner K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and beliefs among Black and Hispanic Americans. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256122.

Redmond ML, et al. Learning from maternal voices on COVID-19 vaccine uptake: perspectives from pregnant women living in the Midwest on the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine. J Community Psychol. 2022;50(6):2630–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22851.

Balasuriya L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and access among Black and Latinx communities. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2128575. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28575.

Butler JZ, et al. COVID-19 vaccination readiness among multiple racial and ethnic groups in the San Francisco Bay Area: a qualitative analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266397.

Dong L, et al. A qualitative study of COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in Black Americans: recommendations for vaccine dissemination and uptake. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0268020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268020.

Majee W, et al. The past is so present: understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among African American adults using qualitative data. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(1):462–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01236-3.

Momplaisir F, et al. Understanding drivers of Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine hesitancy among Blacks. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(10):1784–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab102.

Osakwe ZT, et al. Facilitators of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among Black and Hispanic individuals in New York: a qualitative study. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(3):268–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.11.004.

Sekimitsu S, et al. Exploring COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst Black Americans: contributing factors and motivators. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36(8):1304–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171221099270.

Zhou S, et al. Ethnic minorities’ perceptions of COVID-19 vaccines and challenges in the pandemic: a qualitative study to inform COVID-19 prevention interventions. Health Commun. 2022;37(12):1476–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2093557.

Kerrigan D, et al. Context and considerations for the development of community-informed health communication messaging to support equitable uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among communities of color in Washington, DC. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2023;10(1):395–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01231-8.

Lee Rogers R, Powe N. COVID-19 information sources and misinformation by faith community. Inquiry. 2022;59:469580221081388. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580221081388.

Hwang J. Health information sources and the influenza vaccination: the mediating roles of perceived vaccine efficacy and safety. J Health Commun. 2020;25(9):727–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1840675.

Williamson LD, Tarfa A. Examining the relationships between trust in providers and information, mistrust, and COVID-19 vaccine concerns, necessity, and intentions. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2033. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14399-9.

Parrish-Sprowl J, et al. The AIMS approach: regulating receptivity in patient-provider vaccine conversations. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1120326. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1120326.

Pierz AJ, et al. Supporting US healthcare providers for successful vaccine communication. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):423. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09348-0.

Gargano LM, et al. Impact of a physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(12):2627–33. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.25823.

Oh NL, et al. Provider communication and HPV vaccine uptake: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Prev Med. 2021;148:106554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106554.

Quinn SC, et al. The influence of social norms on flu vaccination among African American and White adults. Health Educ Res. 2017;32(6):473–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyx070.

Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, et al. Leveraging Black pharmacists to promote equity in COVID-19 vaccine uptake within Black communities: a framework for researchers and clinicians. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2022;5(8):887–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jac5.1669.

Cartmell KB, et al. HPV vaccination communication messages, messengers, and messaging strategies. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(5):1014–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1405-x.

Prioli KM, et al. Addressing racial inequality and its effects on vaccination rate: a trial comparing a pharmacist and peer educational program (MOTIVATE) in diverse older adults. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29(8):970–80. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2023.29.8.970.

Xia S, Nan X. Motivating COVID-19 vaccination through persuasive communication: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Health Commun. 2023;1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2023.2218145.

Hunter RF, et al. Social network interventions for health behaviours and outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(9): e1002890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002890.

Robins G, et al. Multilevel network interventions: goals, actions, and outcomes. Social Networks. 2023;72:108–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2022.09.005.

Ortiz RR, et al. Development and evaluation of a social media health intervention to improve adolescents’ knowledge about and vaccination against the human papillomavirus. Glob Pediatr Health. 2018;5:2333794x1877791. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794x18777918.

Ortiz RR, Smith A, Coyne-Beasley T. A systematic literature review to examine the potential for social media to impact HPV vaccine uptake and awareness, knowledge, and attitudes about HPV and HPV vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1465–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1581543.

AuYoung M, et al. Addressing racial/ethnic inequities in vaccine hesitancy and uptake: lessons learned from the California alliance against COVID-19. J Behav Med. 2023;46(1):153–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-022-00284-8.

Kohler RE, et al. Parents’ intentions, concerns and information needs about COVID-19 vaccination in New Jersey: a qualitative analysis. Vaccines. 2023;11(6):1096.

Kutchma ML, et al. Filling the gaps: a community case study in using an interprofessional approach and community-academic partnerships to address COVID-19-related inequities. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1208895. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1208895.

Mansfield LN, et al. Community-based organization perspectives on participating in state-wide community canvassing program aimed to reduce COVID-19 vaccine disparities in California. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1356. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16210-9.

Jaiswal J, Halkitis PN. Towards a more inclusive and dynamic understanding of medical mistrust informed by science. Behav Med. 2019;45(2):79–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2019.1619511.

Stephenson-Hunter C, et al. What matters to us: bridging research and accurate information through dialogue (BRAID) to build community trust and cultivate vaccine confidence. Prev Med Rep. 2023;34:102253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102253.

Corbie-Smith G. Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210434–e210434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0434.

Lazarus JV, et al. Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x.

Hong Y, Hashimoto M. I will get myself vaccinated for others: the interplay of message frame, reference point, and perceived risk on intention for COVID-19 vaccine. Health Commun. 2023;38(4):813–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1978668.

Lin C, et al. Changes in confidence, feelings, and perceived necessity concerning COVID-19 booster. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11:7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11071244.

Lu L, et al. The effects of vaccine efficacy information on vaccination intentions through perceived response efficacy and hope. J Health Commun. 2023;28(2):121–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2023.2186545.

Hwang J, et al. Understanding CDC’s vaccine communication during the COVID-19 pandemic and its effectiveness in promoting positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine. J Health Commun. 2022;27(9):672–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2022.2149968.

Heris CL, et al. Key features of a trauma-informed public health emergency approach: a rapid review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1006513. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1006513.

Cunningham-Erves J, et al. Development of a theory-based, culturally appropriate message library for use in interventions to promote COVID-19 vaccination among African Americans: formative research. JMIR Form Res. 2022;6(7):e38781. https://doi.org/10.2196/38781.

Bass SB, et al. Mapping perceptual differences to understand COVID-19 beliefs in those with vaccine hesitancy. J Health Commun. 2022;27(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2022.2042627.

Kreuter MW, et al. Intention to vaccinate children for COVID-19: a segmentation analysis among Medicaid parents in Florida. Prev Med. 2022;156:106959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.106959.

Feinberg IZ, et al. Strengthening culturally competent health communication. Health Secur. 2021;19(S1):S41-s49. https://doi.org/10.1089/hs.2021.0048.

Salmon DA, et al. LetsTalkShots: personalized vaccine risk communication. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1195751. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1195751.

SAMHSA, Substance abuse and mental health services administration. Treatment improvement protocol for trauma-informed care. TIP 57. 2014.

Public Health Alliance of Southern California, Supporting Communities and Local Public Health Departments During COVID-19 and Beyond: A ROADMAP FOR EQUITABLE AND TRANSFORMATIVE CHANGE. 2022.

Wilson MG, Lavis JN, Guta A. Community-based organizations in the health sector: a scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-10-36.

Larson HJ, et al. Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine. 2014;32(19):2150–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081.

MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

Lin C, et al. Vaccinated yet booster-hesitant: perspectives from boosted, non-boosted, and unvaccinated individuals. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11:3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030550.

Funding

Author REK is funded by the National Cancer Institute (K22 CA258675).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YR conceptualized the study, performed the literature search, and wrote the first draft. REK supervised the project and critically revised the work. All authors contributed to the study design, data analysis, interpretation, writing/editing, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This research did not involve human subject research nor did it require review or approval of an Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabin, Y., Kohler, R.E. COVID-19 Vaccination Messengers, Communication Channels, and Messages Trusted Among Black Communities in the USA: a Review. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01858-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01858-1