Abstract

Community evidenced-based diabetes self-management education (DSME) models have not been examined for feasibility, acceptability, or effectiveness among persons transitioning from prison to the community to independent diabetes self-management (DSM). In a non-equivalent control group design with repeated measures, we examined the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effect of a 6-week, 1-h per week Diabetes Survival Skills (DSS) intervention on diabetes knowledge, distress, self-efficacy, and outcome expectancy for transitioning incarcerated males. Of the 92 participants (84% T2D, 83% using insulin, 40% Black, 20% White, 30% Latino, 66% high school or less, mean age 47.3 years, 84% length of incarceration ≤4 years ), 41 completed the study (22 control/19 intervention [TX]). One-way repeated measures ANOVAs revealed significant changes in diabetes knowledge within each group (C, p = .002; TX, p = .027) at all time points; however, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA showed no differences between groups. Additionally, both groups showed improvement in diabetes-related distress and outcome expectancy with the treatment group experiencing greater and sustained improvement at the 12-week time point. Analysis of focus group data (Krippendorf) revealed acceptance of and enthusiasm for the DSS training and low literacy education materials, the need for skill demonstration, and ongoing support throughout incarceration and before release. Our results highlight the complexity of working with incarcerated populations. After most of the sessions, we observed some information sharing between the intervention and the control groups on what they did in their respective sessions. Due to high attrition, the power to detect effects was limited. Yet, results suggest that the intervention is feasible and acceptable with an increased sample size and refined recruitment procedure. NCT05510531, 8/19/2022, retrospectively, registered

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Among 10,000 incarcerated persons, the rate of diabetes is almost 50% higher (9%), than the general population (6.5%) when matched for sex, age, race, and Hispanic origin [1]. Of these persons living in prison with diabetes, 95% will re-enter the community [2, 3] and are at increased risk for preventable healthcare costs related to their diabetes [4, 5]. Prevention is possible with self-management training and diabetes survival skills (DSS) [6-8]; DSS refers to hypoglycemia and sick day management, insulin administration, and consistent nutrition habits, among others, to prevent acute exacerbations (hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia) of diabetes [6-9], and hospitalizations [8, 10, 11]. Targeting care transitions such as prison release for diabetes survival skills self-management education could improve both short- and long-term outcomes for vulnerable incarcerated persons [7, 8].

Prison programs often lack efficacious diabetes self-management education (DSME) or skill-based programs to prepare citizens with diabetes when transitioning from a highly dependent secure environment to independent community living. There have been efforts to examine the effect of engaging incarcerated persons in blood glucose monitoring on glycemic control [12], and two educational interventions related to medication and diet management [13], but for the most part, persons incarcerated in the US correctional system or those recently released from US prisons have not been included in decades of research involving community dwelling and ethnically diverse persons in numerous effective tailored and culturally relevant group/individual models of DSME for improving diabetes knowledge [14, 15], self-care behavior (SCB) [14-16], and stimulating participation in proactive risk reduction [17, 18] because incarcerated adults are considered a vulnerable population. These adults often have some cognitive dysfunction [19, 20] with lower than average prose, as well as decreased literacy across age, sex, and educational attainment, than those living in community households [21]. With release into the community, these individuals undergo significant stress due to competing demands such as finding housing and employment, which can adversely affect DSM. It is unknown whether the evidence-based DSME strategies used in the general community such as with discharge from the hospital to home are feasible, acceptable, and effective for best supporting the transition of persons from prison in their continued DSM into the community. For example, one study reported that persons within 7 days’ post-prison release, had higher rates of hospitalization for short-term diabetes complications and lower extremity amputations compared to matched controls [4]. Interviews with persons recently released from prison revealed significant stress post-release related to not knowing how and when to take insulin [22]. In another study, respondents reported a lack of knowledge regarding what foods to eat, how to control their blood sugar, take medications, or access health care [23]. At a minimum, persons transitioning from prison to the community have a critical need for DSS. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of implementing a 6-week DSS training intervention in the correctional setting 6–9 months before persons transition from prison to the community.

Specific Aims

The primary aim was to evaluate feasibility of the experimental protocol: H1) Recruitment: 48 eligible persons will consent to participate in the study within 2 months. (H2) Attendance/attrition: 90% of enrolled participants will attend and complete the 6-session DSS Training. (H3) Engagement: 75% of enrolled participants will document responses to workbook questions and record blood glucose and, if applicable, associated diet or activity information. (H4) Intervention implementation: The intervention will be delivered according to the DSS timeline (Table 1) and session outline. (H5) Skill proficiency: Participants will return to demonstrate how to use the blood glucose meter, insulin pen (as indicated), and blood glucose log, and other skills specific to DSS sessions 1–6. The secondary aim was to elicit information during focus groups about the participant’s acceptability of the DSS intervention, including their perspective on participating in the intervention. The tertiary aim was to explore the preliminary efficacy and short-term impact of the DSS Intervention on diabetes knowledge, outcome expectancies, emotional distress, and self-efficacy (Information-Motivation-Behavior Model [IMB] [24, 25] outcomes) at baseline, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks.

Methods

Study Design

A quasi-experimental non-equivalent control group 6-week intervention study with repeated measures at baseline, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks was used to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy measures. Acceptability was evaluated using a qualitative descriptive design with focus group interviewing (FGI).

Sample Inclusion Criteria

Eligible individuals: (1) males having type 1 or 2 diabetes and age 18 and older, any race, or ethnicity; (2) must be able to speak and understand English; (3) are within 6–9 months of being released from prison; and (4) have a Connecticut Department of Corrections (CDOC) security and medical classification allowing participation in group sessions. To allow for a control group in this feasibility study, the PI recruited 48 participants from two male facilities. Persons housed in these prisons have received or are completing an assigned sentence and may be directly released from the facilities to the community or half-way houses. One facility houses slightly fewer incarcerated persons but both have similar ethnic, and racial distributions. Nurses in the two facilities are contracted to provide nursing care to the incarcerated population and function under the same policies and procedures. Typically, incarcerated persons with diabetes receive discharge planning 1 month to 2 weeks before discharge, and it will include unstandardized diabetes education provided by registered nurses. The PI screened 102 potential participants to achieve a total sample of 96 to account for attrition as high as 10%. Previous research [26] has demonstrated that in diabetes behavioral interventions targeting the variable “diabetes knowledge,” an effect size of 0.47–0.68 is achievable at p < .05. Therefore, with a moderate effect size (d = 0.50), p < 0.05, power 0.80, two groups, and an estimated moderate correlation (0.50) between three repeated measures, the power analysis [27] indicated a need for 86 participants.

Procedures

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained from the PI’s university. The PI followed the same IRB-approved recruitment procedures used for a previous study [28]. Recruitment flyers were posted in the facilities, and the PI arranged to meet potential participants to review the study and, if agreeable, proceeded with screening using the IRB approved screening script. Before screening and consent procedures, the PI arranged with the administration of the correctional facilities to be available in the waiting area of the medical clinics during some sessions of the Diabetes Chronic Care clinic to provide information about the study. The PI would read the information on the recruitment flier to the interested incarcerated persons and answer questions about the study. If interested in participating in the study, the PI would arrange to meet the potential participants later for screening, consent, and enrollment. We obtained consent to participate in the DSS intervention and focus group with one consent in the initial consent visit. We had IRB-approved consents for the control and intervention groups outlining study procedures and visits. Low reading capabilities were expected. We read the consent form to all potential participants, and they were told to take as much time as needed to decide. They were asked to verbally report back their understanding of the consent form (Teach Back method). Using the Teach Back technique [29] while watching facial expressions was employed to assess the capacity to consent. Their ability to articulate a primary understanding regarding the consent was accepted as their ability to provide consent. If eligible, the PI obtained informed consent, enrolled the participant, obtained demographics, and screened for health literacy and cognitive impairment using the Short-Test Of Functional Health Literacy for Adults (S-TOFHLA) [30] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [31], respectively, and per the informed consent, asked the participant to sign the CDOC HIPPA release form permitting the PI to access his medication list in the medical or pharmacy record.

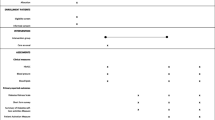

The PI screened potential participants until 48 participants consented and enrolled. Twenty-four participants in the designated treatment facility divided into 2 groups of 12 participated in the same DSS intervention on two separate occasions. Participants (n = 24) in the control facility received the intervention upon completion of week 12 measurements. Table 1 outlines the schedule for the DSS sessions, quantitative assessments, and focus groups.

DSS Intervention

The DSS intervention was informed by the National Standards of Diabetes Education [7] and DSS research [8, 10, 11] and the PI’s prior studies with incarcerated persons with diabetes [32–34] and is grounded in the IMB model [24, 25]. According to the IMB model, a person needs sufficient, accurate information, personal and social motivation, and behavioral skills to successfully implement a health-related behavior change. The current care process used in the state correctional setting does not provide patients with access to a keep on person (KOP) glucose meter; they are allowed to check their blood glucose at prescheduled times in the clinic, but most do not record their blood glucose results [32, 34]. Insulin is administered by correctional nurses, and some patients are allowed oral medications in their cell. In preliminary research with incarcerated persons (N = 124) with diabetes, the PI found almost half of the participants on screening had inadequate health literacy; the majority were using insulin, had significant diabetes knowledge deficits related to hypo/hyperglycemia and key SCBs, allowed within the prison, were not being performed. Additionally, lower personal control beliefs about their ability to affect diabetes outcomes were associated with worse metabolic control [32]. Thirty-five percent of the sample was diagnosed with diabetes while in prison and likely had no experience with self-managing diabetes in the community. Furthermore, A1C levels (a measure of metabolic control) were above the American Diabetes Association’s recommended target of 7% for most participants [8, 18, 32].

The DSS training consisted of six sessions for 1 h once weekly. Each 60-min session followed the same format. For example, the components of S1 the Basics of Diabetes and Preparing for Discharge include (1) program introduction, review confidentiality guidelines, and group expectations and (2) assess participants’ general knowledge about diabetes using interactive low literacy education materials from the Partnership to Improve Diabetes Education (PRIDE) study (at 5th grade reading level) [35]. PRIDE pamphlets for S1 include What is Diabetes and will stimulate discussion around the major problems associated with diabetes, and the major components of self-management. (3) Respond to questions, return demonstration of skills, and distribution of workbook handout one: General Diabetes Information and Preparing for Release. The participant will work on the workbook in his cell and return to the next session for discussion of those questions before we proceeded to S2 class topic. Most of the workbook questions are from the Diabetes Education Prompt Pack [36]. Sample questions include the following: What health problems are people at risk for with diabetes? What are you most concerned about with your diabetes? The PI added setting-specific questions as an adaptation for the setting, including What new or different responsibilities will you take on to take care of your diabetes when you leave prison?; How do manage your stress?; and What affect does stress have your diabetes and blood sugar? All sessions end with a relaxation breathing exercise. Incarcerated persons in this correctional system have used workbooks for another coping skills training intervention [37], and they have been used in other correctional settings as well [38]. The workbook format is familiar to incarcerated persons and acceptable for use in the prison. During the course of the DSS sessions, participants receive blood glucose logs and glucose meters; lancets, testing strips, and demonstration insulin pens with injecting pillow will only be used in class. In summary, the DSS is focused on increasing knowledge, motivation, and self-efficacy and decreasing diabetes-related distress, IMB components relevant to incarcerated persons and proximal to behavior change, through engagement, return demonstrations, skill practice, and positive reinforcement.

Focus Group Procedures

The PI conducted FGI 2 weeks after the end of the DSS training (Table 1). Ten participants were enrolled in each FGI session to account for no-shows.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS V25 statistical package (SPSS, Armonk, New York). Univariate statistics were used to generate summary statistics of demographic and study variables and to answer questions about feasibility. Field notes and attendance sheets were kept to determine recruitment rate, attrition, program completion rates, and intervention fidelity. All instruments were evaluated for reliability. Content analysis was used to analyze focus group data.

To evaluate preliminary efficacy, we conducted 2-way repeated measures ANOVA using the Spoken Knowledge Low Literacy for Diabetes scale (SKILLD) to measure diabetes knowledge, the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) scale to measure diabetes related distress, the Outcome Expectancies Questionnaire (OEQ) to measure a person’s perceptions of the consequences of performing diabetes self-care behavior, and the self-care confidence subscale of the Self-care of Diabetes Inventory (SCODI) which reflects degree of confidence that a patient has about his or her ability to perform a specific self-care-related task. All instruments have demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability in multiple populations not including incarcerated persons. The SKILLD used once in a prior study with incarcerated persons was found to have face and content validity and an Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65. The PAID, OEQ, and SCODI were selected for their applicability to incarcerated person with diabetes and evaluated by experts in correctional health. In the present study, The SKILLD, PAID, SCODI, and OEQ all had Cronbach alphas of 0.80 or greater.

Instruments/Measures

Demographics

Age, gender, ethnicity, type of diabetes, duration of illness and/or age at diagnosis, medications (dose, frequency, and administration method [Keep On Person(KOP), or direct observation]), medical problems, and prior alcohol/substance abuse, and years in prison were measured.

Functional Health Literacy

Reading comprehension was measured by the S-TOFHLA [39]. The S-TOFHLA has been widely used with reported Cronbach’s alpha at 0.97 [39].

Cognitive Function

Measured by the MoCA [31], a rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. Cronbach’s alpha of the MoCA ranges from 0.72 to 0.83 in geriatric, mixed clinical populations and stroke and vascular dementia populations.

Feasibility Measures

Feasibility was evaluated with recruitment and enrollment tracking forms, attendance sheets, field notes, adherence to intervention manual, participant workbook entries, glucose meter procedure manual, and blood glucose logs to obtain data needed to support hypotheses. Reliability of all instruments was evaluated.

Acceptability Measure (Aim 2)

Data was obtained using an IRB approved FGI guide—e.g., probes such as perspective about the overall quality of the program or how well the program prepared participants for transitioning to the community.

Preliminary Efficacy Measures (Aim 3)

-

a.

SKILLD [40], a 10-item scale that measures diabetes knowledge, takes less than 10 min to administer. When used to evaluate knowledge in a population of incarcerated person with diabetes, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.65 and content validity was confirmed in previous research by experts in correctional health [31].

-

b.

SCODI Confidence Subscale [41] measures the degree of confidence the person has about his or her ability to perform specific self-care task and to persist in forming an action despite barriers and has a reported alpha reliability of 0.80.

-

c.

PAID [42], a 20-item scale, measures diabetes-related distress. Internal consistency has been reported at 0.90, and reliability has been consistently high [43].

-

d.

OEQ, a 20-item instrument, measures a “person’s perceptions of the consequences of performing diabetes self-care behavior” [44] and has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 [44]. Perceptions of the consequences of an outcome have been associatively linked to motivation to perform a behavior.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The majority of participants were in their late 30s to 50 years old, with 70% of the sample having a positive screen for cognitive impairment as assessed by the Montreal cognitive assessment score <26, ethnic minority with high school education or less, had T2D, and used insulin. The control group had significantly longer length of incarceration and diabetes diagnosis and lower functional health literacy (Table 2).

Feasibility

Counts, percentiles, measures of central tendency, and correlations were examined to provide information to address each hypothesis in Aim 1. Additionally, quantitative content analysis using a priori themes from AADE Conversation Prompt Pack [36] and from the PI’s experience conducting research with incarcerated persons [28, 32] was used to further assess participant engagement (H3) and intervention implementation (H5).

A total of 102 participants were recruited with 92 of the desired 96 participants enrolled within the 2 months prior to the start of the six-session series. Nineteen of the 46 attended all six sessions, and 65% attended at least three sessions. Workbook completion was poor; the intervention went as planned, and 50% of participants brought in glucose logs for interpretation and discussion. All participated in repeat demonstrations, but more time was needed.

Acceptability

Qualitative data from each FGI transcript (unit of analysis) was analyzed with Krippendorff [45] method of qualitative content analysis. An iterative process of coding and categorizing the data was used to identify themes within and across transcripts. Two researchers read each transcript several times to come to consensus on themes.

Sixteen of 18 participants in the treatment group attended focus group. Overall, participants viewed the intervention favorably with request for skill-based videos. Perspective varied on the adequacy of session length and if person with prediabetes should be included.

Preliminary Efficacy

The effect of the DSS training on the IMB outcome variables was evaluated with repeated measures ANOVA and for the assumptions of repeated measures ANOVA. Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 show the measures of preliminary efficacy with the control group in blue and the treatment group in red. Improvements in diabetes knowledge was seen in both groups and sustained over time in the treatment group, but the intervention effect was not significant (Fig. 1). There were no differences within or between groups for diabetes-related distress, but both groups experience some reduction and the effect was sustained at 12 weeks for the treatment group (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences within or between groups for outcomes expectancies, but scores decreased in the treatment group at 12 weeks. There were no differences within or between group for self-confidence in managing DM and performing self-care behaviors.

Discussion

The DSS intervention was well received by racially and ethnically diverse men, many with mild cognitive impairment, transitioning from prison to the community. The results of this study have implications for enhancing DSMES during the high-stress transition from prison to the community. Additionally, interventions to help persons with chronic illness transitioning to the community may reduce health disparities of the communities to which returning citizens reenter. Although there were some system-related issues that resulted in high attrition, the intervention was feasible and acceptable. The intervention shows promise with participants in both the control and treatment group experiencing some increase in knowledge and decreased diabetes-related distress.

Measures of self-care need to be included in future studies, but this would be difficult to achieve in prison where self-care is constrained. Contrary to persons in prisons, persons completing their sentence in supervised community housing or on parole in the community would have some independence for self-care, and the self-care could be measured. Furthermore, moving the intervention to the supervised community setting or upon release to parole will circumvent some attrition-related problems caused by the movement of incarcerated persons between facilities and other restrictions of movement e.g., lockdown, unpredictability of available community places for persons with DM using insulin, and the unpredictable nature of decision-making by the criminal legal system that determines a person’s release date from prison. For example, during the DSS Intervention, some participants went to court for sentencing review or another matter and were unexpectedly released to a community-supervised setting or parole. Ideally, the DSS or DSME should begin in prison, but meeting returning citizens with diabetes upon release to the community would allow participants of the program to apply the knowledge and skills in less constrained settings.

The study was conducted in two state prisons in the NE housing incarcerated persons who have received or are completing an assigned sentence and may be directly released from the facilities to the community supervised community housing. Persons living in the control group facility likely gained diabetes knowledge before they received the intervention. For example, after completing each set of measurements at baseline, 6, and 12 weeks, participants would leave the area together and discuss the questions on the knowledge questionnaire (Spoken Knowledge for Low Literacy in Diabetes [SKILLD]). Due to the nature of correctional facilities and the process for administering insulin to incarcerated persons with diabetes, the participants likely socialized with each other in the dormitory and common areas—e.g., dining hall, medication line. Given that participants in the control group did experience a significant increase in knowledge before they received the intervention, the interactions and socialization in common living areas and the medication line may have influenced the final results and caused contamination. For future studies, we will need to recruit larger samples to offset the confounding issues in the control facility and think creatively about how to administer questionnaires to a control group. One option may be to deliver the intervention to persons after release to supervised community housing facilities or upon release to parole and randomly assign participants to the intervention or control group.

There were no significant differences within or between groups for outcomes expectancies, but a decrease in the treatment group scores at 12 weeks is a clinically significant finding. Outcome expectancy relates to a person’s belief about the consequences of performing a behavior like diabetes self-management or the belief that performing the behavior would lessen the health consequence. Outcome expectancies are considered an essential precursor for behavior change and are closely associated with motivation. It is possible that the six-session DSS intervention is too short to sustain a long-term effect on outcome expectancies. In future studies, we could add more sessions or a repeated dose of the same sessions to increase outcome expectancy scores and, as a result, motivation and performance of DSM.

The control group had a significantly longer length of incarceration and diabetes diagnosis and lower functional health literacy than the intervention group. One might expect the control group with a longer length of incarceration and length of diabetes diagnosis to have greater knowledge about their diabetes, but in this study, the control group began with lower scores on diabetes knowledge than the intervention group. The lower health literacy of the control group did not seem to affect their ability to increase their knowledge of diabetes. The groups did not differ significantly on race, ethnicity, age, or cognitive impairment. Future studies with larger samples should consider controlling for these variables.

For the past few years, the pandemic has significantly affected correctional settings and the persons living in them. Group and educational programs have been restricted and, in many cases, prohibited entirely [46]. In most national correctional settings, these restrictions will continue due to the surge of variants and the prolonged pandemic crisis [47]. To increase access to the intervention during the COVID 19 pandemic and provide just in time education immediately upon release to the community or supervised community housing, we recommend developing a mobile/electronic version of DSS program for tablet/smart phone. Providing citizens returning to the community from prison with just-in-time self-management education for their diabetes in a virtual environment may be their first point of contact with a diabetes care and education specialist. Additionally, transition planning post-DSS intervention should include linkages to community health workers with history of incarceration experience [48] and DM. After the effectiveness of the DSS program has been determined, we recommend future studies follow returning citizens to the community to include measurement of distal outcomes—e.g. ED use, hospitalization, A1C, QOL, and issues around health equity, e.g., access to primary care and post-release diabetes education. System and reentry issues around unscheduled release from prison to community partners/halfway houses should be addressed with health policy at the state level.

Limitations

As a feasibility study, the study was underpowered and included only males. The high security environment, unexpected events within DOC facilities, and unpredictable transfers to supervised community living led to attrition.

Conclusion

The proposed research tested the feasibility and acceptability of a DSME intervention in a unique and challenging environment involving a vulnerable population with an undue burden of unmet needs and health disparities with a focus on the less studied DSS. The results of the proposed research provides a starting point to guide research in the area of DSM for this vulnerable population. Findings from this research were used to modify the intervention and inform an ongoing study with a larger sample size and in a location where participants have some independence from self-care such as supervised community housing or on parole.

References

Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report; 2015. p. 1–23.

Maruschak LM, Bronson J, Aber M. Medical problems reported by prisoners: survey of prison inmates. Bur Justice Stat Spec Rep. 2016;2021:1–11.

Wang EA, Wildeman C. Studying health disparities by including incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1708–9.

Wang EA, Krumholz HM. A high risk of hospitalization following release from correctional facilities in Medicare beneficiaries: a retrospective matched cohort study, 2002 to 2010. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013;173(17):1621–8.

Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, Kushel MB. Engaging individuals recently released from prison into primary care: a randomized trial. Am. J. Public Health. 2012;102(9):e22–9.

Magee MF, Khan NH, Desale S, Nassar CM. Diabetes to go knowledge-and competency-based hospital survival skills diabetes education program improves postdischarge medication adherence. Diab Educ. 2014;40(3):344–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714523684. Epub 2014 Feb 20

Powers MA, Bardsley JK, Cypress M, Funnell MM, Harms D, Hess-Fischl A, Hooks B, Isaacs D, Mandel ED, Maryniuk MD, Norton A, Rinker J, Siminerio LM, Uelmen S. Diabetes self-management education and support in adults with Type 2 diabetes: a consensus report of the American Diabetes Association, the Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of PAs, the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, and the American Pharmacists Association. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1636–49. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci20-0023.

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 16. Diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl. 1):S244–53.

Healy SJ, Black D, Harris C, Lorenz A, Dungan KM. Inpatient diabetes education is associated with less frequent hospital readmission among patients with poor glycemic control. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;36(10):2960–7.

Krall JS, Donihi AC, Hatam M, Koshinsky J, Siminerio L. The Nurse Education and Transition (NEAT) model: educating the hospitalized patient with diabetes. Clin Diab Endocrinol. 2016;2(1):1.

Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, DiNardo M, Einhorn D, Hellman R, Hirsch IB, Umpierrez GE. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association consensus statement on inpatient glycemic control. Diab Care. 2009;32(6):1119–31.

Hunter Buskey RN, Mathieson K, Leafman JS, Feinglos MN. The effect of blood glucose self-monitoring among inmates with diabetes. J. Correct. Health Care. 2015;21(4):343–54.

Dhaliwal KK, Johnson NG, Lorenzetti DL, Campbell DJT. Diabetes in the context of incarceration: a scoping review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;13(55):101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101769. PMID: 36531980; PMCID: PMC9755063

Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015;99

Fan L, Sidani S. Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education intervention elements: a meta-analysis. Can. J. Diab. 2009;33(1):18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-2671(09)31005-98.

Newlin Lew K, Nowlin S, Chyun D, Melkus G. State of the science: diabetes self-management interventions led by nurse principal investigators. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2014;36(9):1111–57.

Kent D, D'Eramo MG, Stuart PM, McKoy JM, Urbanski P, Boren SA, Coke L, Winters JE, Horsley NL, Sherr D, Lipman R. Reducing the risks of diabetes complications through diabetes self-management education and support. Popul. Health Manag. 2013;16(2):74–81. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2012.0020.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2022 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diab. 2022;40(1):10–38. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd22-as01. PubMed:35221470

Cavanagh JF, Frank MJ, Allen JJ. Social stress reactivity alters reward and punishment learning. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2011;6(3):311–20.

Todd S, Reagan L, Laguerre R. Health literacy, cognitive impairment, and diabetes knowledge among incarcerated persons transitioning to the community: considerations for intervention development. J. Forensic Nurs. 2022;10. https://doi.org/10.1097/JFN.0000000000000396. Epub ahead of print

Greenberg E, Dunleavy E, Kutner M. Literacy behind bars: results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy Prison Survey. In: NCES 2007-473. National Center for Education Statistics; 2007.

Thomas EH, Wang EA, Curry LA, Chen PG. Patients’ experiences managing cardiovascular disease and risk factors in prison. Health Justice. 2016;4(1):1.

Salem BE, Nyamathi A, Idemundia F, Slaughter R, Ames M. At a crossroads: reentry challenges and healthcare needs among homeless female ex-offenders. J. Forensic Nurs. 2013;9(1):14–22.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Amico KR, Harman JJ. An information-motivation-behavioral skills model of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(4):462–73.

Osborn CY, Egede LE. Validation of an information-motivation-behavioral skills model of diabetes self-care (IMB-DSC). Patient Educ. Couns. 2010;79(1):49–54.

Brown SA. Meta-analysis of diabetes patient education research: variations in intervention effects across studies. Res. Nurs. Health. 1992;15(6):409–19.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 2007;39:175–91.

Reagan L, Walsh SJ, Shelton D. Relationships of illness representation, diabetes knowledge, and self-care behavior to glycemic control in incarcerated persons with diabetes. Int. J. Prison. Health. 2016;12(3):157–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-04-2015-0010.

Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:83–90.

Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ. Couns. 1999;38:33–42.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Reagan L. Inmates health beliefs about diabetes: implications for diabetes education in the correctional setting. Proceedings of Custody and caring: 12th Biennial International Conference on the Nurse’s Role in the Criminal Justice System. Saskatoon, SK; 2011 (IRB # ).

Reagan L, Shelton D, Anderson E. Rediscovery of self-care for incarcerated persons with diabetes. J Evid-Based Pract Correct Health. 2016;1(1). http://digitalcommons.uconn.edu/jepch/vol1/iss1/5. Accessed 2/2/2021

Reagan L, Shelton D. Methodological factors conducting research with incarcerated persons with diabetes. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016;29:163–7.

Wolff K, Chambers L, Bumol S, White RO, Gregory BP, Davis D, Rothman RL. The PRIDE (Partnership to Improve Diabetes Education) toolkit development and evaluation of novel literacy and culturally sensitive diabetes education materials. The Diabetes Educ. 2016;42(1):23–33.

American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE). Diabetes education prompt deck. Educator Guide; 2016.

Sampl S, Wakai S, Trestman RL, Keeney EM. Functional analysis of behavior in corrections: empowering inmates in skills training groups. J Behav Anal Offender Vict Treat Prev. 2008;1(4):42.

Joe GW, Knight K, Simpson DD, Flynn PM, Morey JT, Bartholomew NG, Tindall MS, Burdon WM, Hall EA, Martin SS, O'Connell DJ. An evaluation of six brief interventions that target drug-related problems in correctional populations. J. Offender Rehabil. 2012;51(1-2):9–33.

Rothman R, Malone R, Bryant B, Wolfe C, Padgett P, DeWalt D, Weinberger M, Pignone M. The spoken knowledge in low literacy in diabetes scale. Diab Educ. 2005;31(2):215–24.

Ausili D, Barbaranelli C, Rossi E, et al. Development and psychometric testing of a theory-based tool to measure self-care in diabetes patients: the self-care of diabetes inventory. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-017-0218-y

Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH. The problem areas in diabetes scale: an evaluation of its clinical utility. Diab Care. 1997;20:760–6.

Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, Schwartz CE. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diab Care. 1995;18:754–60.

Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, Riddle M, Donnelly J, Mitchell DL, Calder D. Diabetes-specific social learning variables and self-care behaviors among persons with type II diabetes. Health Psychol. 1989;8(3):285.

Chlebowy DO, Garvin BJ. Social support, self-efficacy, and outcome expectations impact on self-care behaviors and glycemic control in Caucasian and African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721706291760.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2019.

Davis LM, Turner S, Tolbert MC, Kirkegaard A, Weidmer BA. Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 on prison education: survey results. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2023. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2122-1.html.

Tan ST, Kwan AT, Rodríguez-Barraquer I, et al. Infectiousness of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections and reinfections during the Omicron wave. Nat Med. 2023;29:358–65. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-02138-x.

Hawks LC, Horton N, Wang EA. The health and health needs of people under community supervision. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162221119661.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the administration, Wardens/Deputy Wardens, Nursing Staff, and Correctional Officers at the Connecticut Department of Corrections (CDOC) for study approval and ongoing support and Dr. Russell Rothman, Vanderbilt University, and PI of the Partnership to Improve Diabetes Education (PRIDE) Study and the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) for use of their education Materials.

Funding

This work was supported by the American Nurses Foundation (Grant #ID6046) and the University of Connecticut Office of Vice Provost Research Scholarship Facilitation Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Louise Reagan, Rick Laguerre, and Sarah Todd. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Louise Reagan, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut (H17-006 March 8, 2017).

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Reagan, L., Laguerre, R., Todd, S. et al. The Feasibility and Acceptability of a Diabetes Survival Skills Intervention for Persons Transitioning from Prison to the Community. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 1014–1023 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01581-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01581-x