Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has uncovered clinically meaningful racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related health outcomes. Current understanding of the basis for such an observation remains incomplete, with both biomedical and social/contextual variables proposed as potential factors.

Purpose

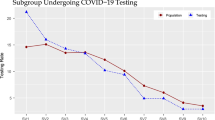

Using a logistic regression model, we examined the relative contributions of race/ethnicity, biomedical, and socioeconomic factors to COVID-19 test positivity and hospitalization rates in a large academic health care system in the San Francisco Bay Area prior to the advent of vaccination and other pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19.

Results

Whereas socioeconomic factors, particularly those contributing to increased social vulnerability, were associated with test positivity for COVID-19, biomedical factors and disease co-morbidities were the major factors associated with increased risk of COVID-19 hospitalization. Hispanic individuals had a higher rate of COVID-19 positivity, while Asian persons had higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalization. The excess hospitalization risk attributed to Asian race was not explained by differences in the examined biomedical or sociodemographic variables. Diabetes was an important risk factor for COVID-19 hospitalization, particularly among Asian patients, for whom diabetes tended to be more frequently undiagnosed and higher in severity.

Conclusion

We observed that biomedical, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic factors all contributed in varying but distinct ways to COVID-19 test positivity and hospitalization rates in a large, multi-racial, socioeconomically diverse metropolitan area of the United States. The impact of a number of these factors differed according to race/ethnicity. Improving overall COVID-19 health outcomes and addressing racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes will likely require a comprehensive approach that incorporates strategies that target both individual-specific and group contextual factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gamble VN. There wasn’t a lot of comforts in those days: African Americans, Public Health, and the 1918 influenza epidemic. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(Suppl 3):114–22.

Krishnan L, Ogunwole SM, Cooper LA. Historical insights on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the 1918 influenza pandemic, and racial disparities: Illuminating a path forward. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:474–81.

Crosby AW Jr. Epidemic and peace, 1918. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1976.

Poulson M, Neufeld M, Geary A, Kenzik K, Sanchez SE, Dechert T, et al. Intersectional Disparities Among Hispanic Groups in COVID-19 Outcomes. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;23(1):4–10.

Tirupathi R, Muradova V, Shekhar R, Salim SA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Palabindala V. COVID-19 disparity among racial and ethnic minorities in the US: A cross sectional analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38:101904.

Gu T, Mack JA, Salvatore M, Prabhu Sankar S, Valley TS, Singh K, et al. Characteristics associated with racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes in an academic health care system. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025197-7.

COVID Tracker; 2021 [cited December 12, 2021]. Available from: https://covidtracking.com/race.

Cho WKT, Hwang DG. Differential effects of race/ethnicity and social vulnerability on COVID-19 positivity, hospitalization, and death in the San Francisco Bay area. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;3:1–10.

Acosta AM, Garg S, Pham H, Whitaker M, Anglin O, O’Halloran A, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of COVID-19-associated hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital death in the United States From March 2020 to February 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130479.

Shiels MS, Haque AT, Haozous EA, Albert PS, Almeida JS, García-Closas M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to December 2020. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1693–703.

Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, Saha S, Advani SM, Young S, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(3):362–86.

Bohn S, Bonner D, Lafortune J, Thorman T. Income inequality and economic opportunity in California. Public Policy Institute of California, Dec 2020; 2020. Available from: https://www.ppic.org/wp-content/uploads/incoming-inequality-and-economic-opportunity-in-california-december-2020.pdf.

Ross AM, Treuhaft S. Who is low-income and very low income in the Bay Area?; 2020 [cited December 12, 2021]. Available from: https://nationalequityatlas.org/node/60841.

Office of Civid Engagement & Immigrant Affairs: Language Diversity Data; 2022 [cited March 10]. Available from: https://sfgov.org/ccsfgsa/oceia/language-diversity-data.

Cortright J. Identifying American’s most diverse. City Observatory: Mixed Income Neighborhoods; 2018.

Deng G, Yin M, Chen X, Zeng F. Clinical determinants for fatality of 44,673 patients with COVID-19. Critical Care. 2020;24(1):Article number 179.

Zhu L, She ZG, Cheng X, Qin JJ, Zhang XJ, Cai J, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metabolism. 2020;31(6):1068–77.

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–6.

Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, Raverdy V, Noulette J, Duhamel A, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity. 2020;28(7):1195–9.

Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S, Sterling S, Johnson D, Francois F, et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for COVID-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):896–7.

Klang E, Kassim G, Soffer S, Freeman R, Levin MA, Reich DL. Severe obesity as an independent risk factor for COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized patients younger than 50. Obesity. 2020;28(9):1595–9.

Cutter SL. The vulnerability of science and the science of vulnerability. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2003;93(1):1–12.

Flores A. 2015, Hispanic population in the United States: Statistical portrait statistical portrait of hispanics in the United States. Pew Research Center; 2017.

Budiman A, Ruiz NG. Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. Pew Research Center; April 29, 2021.

Phillips S, Wyatt L, Turner M, Trinh-Shevrin C, Kwon S. Patient-provider communication patterns among Asian American Patient-provider communication patterns among Asian American Patient-provider communication patterns among Asian American immigrant subgroups in New York City. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(5):1049–58.

Seo J, Kuerban A, Bae S, Strauss S. Disparities in Health care utilization between Asian immigrant women and non-Hispanic White women in the United States. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28:1368–77.

Joo J, Rostov P, Feeser S, Berkowitz S, Lyketsos C. Engaging an Asian immigrant older adult in depression care: Collaborative care, patient-provider communication and ethnic identity. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(12):1267–73.

Jang B, Kim M. Limited English proficiency and health service use in Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(2):264–70.

Felicilda-Reynaldo R, Choi S, ad C Albright SD. A national survey of complementary and alternative medicine use for treatment among Asian-Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(4):762–70.

Gee G, Ro A, S SSM, Chae D. Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:130–51.

Lee H, Rhee T, Kim N, Ahluwalia J. Health literacy as a social determinant of health in Asian American immigrants: Findings from a population-based survey in California. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1118–24.

Lee E, Blacher K. Asian American and pacific islander older workers: Employment trends. National Asian Pacific Center on Aging; 2013.

Merzon E, Green I, Shpigelman M, Vinker S, Raz I, Golan-Cohen A, et al. Haemoglobin A1c is a predictor of COVID-19 severity in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2021;37(5):e3398.

Olaogun I, Farag M, Hamid P. The pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus in non-obese individuals: An overview of the current understanding. Cureus. 2020;12(4):e7614.

Araneta MRG, Kanaya AM, Hsu WC, Chang HK, Grandinetti A, Boyko EJ, et al. Optimum BMI cut points to screen Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):814–20.

Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021–9.

Cheng YJ, Kanaya AM, Araneta, Saydah SH, Kahn S, Gregg EW, et al. Prevalence of diabetes by race and ethnicity in the United States, 2011-2016. JAMA. 2019;322(24):2389–98.

McCloskey JK, Ellis JL, Uratsu CS, Drace ML, Ralston JD, Bayliss EA, et al. Accounting for social risk does not eliminate race/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 infection among insured adults: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:1183–90.

Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, Soltesz L, Chen YFI, Parodi SM, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes: Retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(6):786–93.

California Health Care Foundation. San Francisco Bay Area: Regional Health Systems Vie for Market Share; 2021. Available from: https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/RegionalMarketAlmanac2020BayArea.pdf [cited May 6, 2021].

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Ashly Dyke for assistance with the literature review. This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562. Computing resources were granted through the HPC Consortium for access to Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center’s Bridges, Bridges-2, and Bridges-AI.

Funding

This research was supported in part by unrestricted grants to DGH from All May See (formerly That Man May See) and to DGH from Research to Prevent Blindness.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: both authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: both authors. Drafting of the manuscript: both authors. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: both authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of California San Francisco Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board (IRB #2030987. Reference #324788).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, W.K.T., Hwang, D.G. Racial/Ethnic, Biomedical, and Sociodemographic Risk Factors for COVID-19 Positivity and Hospitalization in the San Francisco Bay Area. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 1653–1668 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01351-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01351-1