Abstract

Background

In Latino(a) communities, promotores de salud (i.e., community health workers; promotores) are becoming critical participants in prevention, health promotion, and the delivery of health care. Although involving culturally diverse participants in research is a national priority, recruitment and retention of research participants from these groups is challenging. Therefore, there is an increased need to identify strategies for successful recruitment of participants from underrepresented minority backgrounds. Our overall study purpose was to gain promotores’ perspectives on recruiting Latino(a) immigrant community members for an intervention study on autism spectrum disorders (ASD). The goal of this paper is to explore insider promotores’ views on the barriers and facilitators to research participation in the Latino(a) community and learn strategies for recruiting Latino(a) participants in a nontraditional destination city.

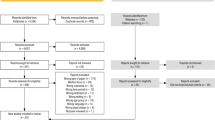

Methods

We conducted qualitative focus groups with an established group of promotores known as Latinos Unidos por la Salud (LU-Salud), who were members of a community-academic research team. Fifteen LU-Salud promotores participated in the focus groups. Focus group interviews were analyzed by using Leininger’s data analysis enabler. These results will inform our partnerships with promotores and Latino(a) neighborhood agencies to increase recruitment for community-based research on promoting awareness of ASD among Latino(a) families.

Results

Promotores were credible community members able to gain community trust and committed to improving the health and well-being of their Latino(a) community, including involving them in research. Latino(a) research involvement meant facilitating community members’ engagement to overcome barriers of distrust around legal and health care systems. Challenges included legal uncertainties, language and literacy barriers, health knowledge, and economic hardship. Promotores also voiced the diversity of cultural practices (subcultures) within the Latino(a) culture that influenced: (1) research engagement, (2) guidance from promotores, (3) immersion in the Latino(a) community, and (4) health and well-being. Experienced promotores, who are living in a nontraditional migration area, believe the primary facilitator to increasing research involvement is Latino(a)-to-Latino(a) recruitment.

Conclusions

These findings will aid in building partnerships to recruit participants for future studies that promote early recognition of ASD in the Latino(a) community.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. Healthy People 2020. http://healthypeoplegov/2020/topicsobjectives2020.

Cabral DN, Napoles-Springer AM, Miike R, McMillan A, Sison JD, Wrensch MR, et al. Population- and community-based recruitment of African Americans and Latinos: the San Francisco Bay Area Lung Cancer Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(3):272–9.

Magana S, Lopez K, Machalicek W. Parents taking action: a psycho-educational intervention for Latino parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Fam Process. 2015.

Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Reyes NM, Chavez AE, Macias K, Smith KN, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and non-Latino White families. Pediatrics. 2017;139:5.

Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Pelley T, Topmiller M. Healthcare experiences of Latinos in a nontraditional destination area. J Community Pract. 2015;23(1):76–101.

Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhen-Duan J, Graham C, Marschner D, Peralta J, et al. Latinos Unidos por la Salud: the process of developing an immigrant community research team. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice. 2017;1(1):2.

Jacquez F, Vaughn LM, Suarez-Cano G. Implementation of a stress intervention with Latino immigrants in a non-traditional migration city. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(2):372–82.

Ray MA, Morris E, McFarland M. Ethnonursing method of Dr. Madeleine Leininger. In: Beck CT, editor. Routledge International Handbook of Qualitative Nursing Research. New York: Routledge. 2013:213–29.

Burkett K, Morris E. Enabling trust in qualitative research with culturally diverse participants. J Pediatr Health Care. 2015;29(1):108–12.

WestRasmus EK, Pineda-Reyes F, Tamez M, Westfall JM. Promotores de salud and community health workers: an annotated bibliography. Fam Community Health. 2012;35(2):172–82.

Messias DK, Parra-Medina D, Sharpe PA, Trevino L, Koskan AM, Morales-Campos D. Promotoras de Salud: roles, responsibilities, and contributions in a multisite community-based randomized controlled trial. Hisp Health Care Int. 2013;11(2):62–71.

American Public Health Association. Community Health Workers. http://wwwaphaorg/membergroups/sections/aphasections/chw/. 2010.

Stacciarini JM, Rosa A, Ortiz M, Munari DB, Uicab G, Balam M. Promotoras in mental health: a review of English, Spanish, and Portuguese literature. Family & community health. 2012;35(2):92–102.

Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Zhen-Duan J. Perspectives of community co-researchers about group dynamics and equitable partnership within a community–academic research team. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(5):682–9.

García AA, Zuñiga JA, Lagon C. A personal touch: the most important strategy for recruiting Latino research participants. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28(4):342–7.

Cupertino AP, Suarez N, Cox LS, Fernandez C, Jaramillo ML, Morgan A, et al. Empowering Promotores de Salud to engage in community-based participatory research. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2013;11(1):24–43.

Kandel W, Parrado EA. Restructuring of the US meat processing industry and new Hispanic migrant destinations. Popul Dev Rev. 2005;31;(3):447.

Rios-Ellis B, Nguyen-Rodriguez ST, Espinoza L, Galvez G, Garcia-Vega M. Engaging community with promotores de salud to support infant nutrition and breastfeeding among Latinas residing in Los Angeles County: Salud con Hyland's. Health care for women international. 2015;36(6):711–29.

de Heer HD, Balcazar HG, Wise S, Redelfs AH, Rosenthal EL, Duarte MO. Improved cardiovascular risk among Hispanic border participants of the Mi Corazón Mi Comunidad Promotores de Salud Model: the HEART II cohort intervention study 2009–2013. Front Public Health. 2015;3:149.

Parrado EA, McQuiston C, Flippen CA. Participatory survey research - Integrating community collaboration and quantitative methods for the study of gender and HIV risks among Hispanic migrants. Sociol Methods Res. 2005;34(2):204–39.

Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. Choice: current reviews for academic libraries. 2014;51(5):827.

Rifie HA, Turner S, Rojas-Guyler L. The diverse faces of Latinos in the Midwest: planning for service delivery and building community. Health Soc Work. 2008;33(2):101–10.

Centers for Disease Control aP. Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey. 2018 Table A-4 2018 [diabetes stats]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm.

Centers for Disease Control aP. Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey. 2018 Table A-8 2018 [mental health conditions]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/shs/tables.htm

Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan VW, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. Variability in cancer risk and outcomes within US Latinos by national origin and genetic ancestry. Current epidemiology reports. 2016;3(3):181–90.

Sun CJ, García M, Mann L, Alonzo J, Eng E, Rhodes SD. Latino sexual and gender identity minorities promoting sexual health within their social networks: process evaluation findings from a lay health advisor intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(3):329–37.

Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020;69(4):1–12.

Christensen DL, Baio J, Braun KV, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1–23.

Kamimura-Nishimura K, Froehlich T, Chirdkiatgumchai V, Adams R, Fredstrom B, Manning P. Autism spectrum disorders and their treatment with psychotropic medications in a nationally representative outpatient sample: 1994–2009. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(7):448–53. e1.

Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ, Schieve LA, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Prevalence and trends of developmental disabilities among children in the United States: 2009–2017. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190811.

Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1):e20193447.

Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–23.

Zuckerman K, Mattox K, Donelan K, Batbayar O, Baghaee A, Bethell C. Pediatrician identification of Latino children at risk for autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2013.

Jarquin V, Wiggins L, Schieve L, Van Naarden-Braun K. Racial disparities in community identification of autism spectrum disorders over time; Metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia, 2000-2006. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32(3):179–87.

Bornstein MH, Cote LR. “Who is sitting across from me?” Immigrant mothers’ knowledge of parenting and children’s development. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):e557–64.

Magaña S, Lopez K, Aguinaga A, Morton H. Access to diagnosis and treatment services among Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2013;51(3):141–53.

Chaidez V, Hansen RL, Hertz-Picciotto I. Autism spectrum disorders in Hispanics and non-Hispanics. Autism. 2012;16(4):381–97.

Flores G. Committee On Pediatric R. Technical report--racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e979–e1020.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agenor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–63.

Magaña S, Parish S, Morales MA, Li H, Fujiura G. Racial and ethnic health disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Las Disparidades Raciales yÉtnicas de Salud Entre Personas con Discapacidad Intelectual y del Desarrollo. 2016;54(3):161–72.

Vaughn LM, Whetstone C, Boards A, Busch MD, Magnusson M, Määttä S. Partnering with insiders: a review of peer models across community-engaged research, education and social care. Health & social care in the community. 2018;26(6):769–86.

McFarland M, Wehbe-Alamah H. Leininger's Culture Care Diversity and Universality: a worldwide nursing theory. Jones & Bartlett: Burlington, MA; 2015.

Berry AB. Culture care of the Mexican American family. In: Leininger M, McFarland MR, editors. Transcultural nursing: concepts, theories, research, and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2002. p. 363–73.

Wehbe-Alamah H, McFarland M. Leininger’s ethnonursing research method: historical retrospective and overview. J Transcult Nurs. 2020;1043659620912308.

Cote-Arsenault D. Focus Groups. In: Beck CT, editor. Routledge International Handbook of Qualitative Nursing Research. New York: Routledge; 2013. p. 307–18.

Bazeley P, Jackson K. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. 3rd ed. SAGE: Los Angeles, CA; 2013.

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2018.

Bojorquez GR, Fry-Bowers EK. Beyond eligibility: access to federal public benefit programs for immigrant families in the United States. J Pediatr Health Care. 2019;33(2):210–3.

Zuckerman K, Lindly O, Reyes N, Chavez A, Macias K, Smith K, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and treatment of autism in Latino and Non-Latino white families. Pediatrics. 2017;139:5.

Vaughn LM, Jacquez F, Baker RC. Cultural health attributions, beliefs, and practices: effects on healthcare and medical education. Mental. 2009;10:11.

Jacquez F, Vaughn L, Zhen-Duan J, Graham C. Health care use and barriers to care among Latino immigrants in a new migration area. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1761–78.

Torres L. Predicting levels of Latino depression: acculturation, acculturative stress, and coping. J Cultural Diversity Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(2):256–63.

Caplan S. Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: a dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice. 2007;8(2):93–106.

Arbona C, Olvera N, Rodriguez N, Hagan J, Linares A. Wiesner MJHJoBS. Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. 2010;32(3):362–84.

Acknowledgements

This study represents a collaborative effort between the authors, promotores, and local community organizations. We are deeply grateful to the promotores for their significant contributions to this work.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the need to preserve confidentiality for the participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding

The Cincinnati Center for Clinical and Translational Science and Training (CCTST) funded this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have participated in (a) conception and design or analysis and interpretation of the data; (b) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and (c) approval of the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center provided the Institutional Review Board approval to conduct this study. Informed consents were obtained for all participants in this study.

Consent for publication

Provided.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burkett, K., Kamimura-Nishimura, K.I., Suarez-Cano, G. et al. Latino-to-Latino: Promotores’ Beliefs on Engaging Latino Participants in Autism Research. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9, 1125–1134 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01053-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01053-0