Abstract

Aims

It is unclear how ethnic differences in HbA1c levels are affected by individual variations in mental wellbeing. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the extent to which HbA1c disparities between Caucasian and South Asian adults are mediated by various aspects of positive psychological functioning.

Methods

Data from the 2014 Health Survey for England was analysed using bootstrapping methods. A total of 3894 UK residents with HbA1c data were eligible to participate. Mental wellbeing was assessed using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale. To reduce bias BMI, blood pressure, diabetes status, and other factors were treated as covariates.

Results

Ethnicity directly predicted blood sugar control (unadjusted coefficient −2.15; 95% CI −3.64, −0.67), with Caucasians generating lower average HbA1c levels (37.68 mmol/mol (5.6%)) compared to South Asians (39.87 mmol/mol (5.8%)). This association was mediated by positive mental wellbeing, specifically concerning perceived vigour (unadjusted effect 0.30; 95% CI 0.13, 0.58): South Asians felt more energetic than Caucasians (unadjusted coefficient −0.32; 95% CI −0.49, −0.16), and greater perceived energy predicted lower HbA1c levels (unadjusted coefficient −0.92; 95% CI −1.29, −0.55). This mediator effect accounted for just over 14% of the HbA1c variance and was negated after adjusting for BMI.

Conclusions

Caucasian experience better HbA1c levels compared with their South Asian counterparts. However, this association is partly confounded by individual differences in perceived energy levels, which is implicated in better glycaemic control, and appears to serve a protective function in South Asians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Poor glycaemic control is a major threat to public health [1, 2]. With steadily rising diabetes prevalence and incidence rates [3], the cost of hospitalisation related to poor glycaemic control is an increasing concern [4]. For example, in the UK, diabetes mellitus currently costs the health service over £10 billion annually [4]. A reduction in the length of hospital admission of just 0.61 days can save a health organisation over £400,000 [4]. Hospitalisation typically results from short and/or long-term complications associated with poor blood sugar (i.e. glycaemic) control [5]. Thus, improving blood sugar control can significantly reduce the costs of diabetes-related care [1], reducing the economic burden of the disease [4].

People from ethnic minority groups are at greater risk of elevated blood sugar levels [6, 7]. South Asians (e.g. Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi) in particular are 2.6 times more likely to be admitted to hospital for diabetes, compared to Caucasians [8]. The excess hospitalisation risk in South Asian patients may denote higher complication rates resulting from poor blood sugar control [1, 5, 9–11]. Although some evidence suggests no ethnic differences in blood glucose levels [12], other research indicates poorer glycaemic control amongst South Asian patients relative to Caucasians [13]. Thus, blood sugar control is especially important for South Asian patients [14].

Average blood sugar control over time is gauged using HbA1c (glycated haemoglobin) test [5]. This test gives an indication of blood sugar concentration over the previous 2–3 months [15]. Test results are calibrated in percentages (values ≤6.5% indicating good blood sugar control), or millimoles per mole (values ≤48 mmol/mol denoting adequate glycaemic control). HbA1c values of 6–6.4% (42–47 mmol/mol) indicates pre-diabetes, meaning a high risk of developing diabetes, while values ≥48 mmol/mol may denote diabetes [16]. A normal non-diabetic HbA1c value is <36 mmol/mol (5.5%). Pre-diabetes is a clinically relevant state, as patients with this condition have an elevated risk of developing microvascular and macrovascular morbidities (e.g. coronary disease), and also type 2 diabetes [17]. Lifestyle and pharmacological interventions targeting pre-diabetes cases can help delay the onset of type 2 diabetes [17].

Lowering HbA1c levels reduces the risk of long-term health problems, notably diabetes-related complications [1]. In many western countries, people diagnosed with pre-diabetes or diabetes are expected to undergo a HbA1c test regularly (e.g. once or twice a year) [15]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has recommended that the HbA1c can also be used to diagnose type 2 diabetes in otherwise healthy people who are not currently diagnosed with diabetes or pre-diabetes [16, 18, 19].

A number of studies have compared HbA1c outcomes in Caucasian and South Asian patients [12, 20–25]. For example, one study assessed HbA1c outcomes in Caucasian and South Asian young adults attending a diabetes clinic [12]. While HbA1c levels improved several years following diagnosis, they found no ethnic differences in glycaemic control. Another investigation assessed HbA1c in South Asian and Caucasian women with a history of gestational diabetes and also found similar HbA1c values across the groups [20]. However, an investigation of ethnic differences in HbA1c outcomes amongst adults with normal glucose tolerance found higher HbA1c levels in the South Asian participants (6.11 ± 0.58%) compared to their Caucasian counterparts (5.90 ± 0.40%) [21]. Another study also found a significant HbA1c excess in South Asian patients, compared with Caucasians [22], partly attributing the differential to physiological mechanisms. Research on HbA1c levels in children also show higher levels in South Asians, compared with Caucasians [23].

It is unclear to what extent ethnic differences in blood sugar control can be explained by variations in mental wellbeing. Some research has examined the association between psychological wellbeing and HbA1c outcomes, with mixed results [24, 26–28]. One study assessed the relationship between anxiety and HbA1c levels in South Asians and Caucasians and found no association [24]. Overall, however, none of the studies cited above, or others reported in the literature [25], have specifically examined the extent to which ethnic disparities in HbA1c values are affected by positive psychological dispositions, such as decisiveness, feelings of self-worth, or empathy for others [29]. Poor mental wellbeing is associated with poorer diabetes self-management behaviours, including poor dietary habits, physical inactivity, and insufficient blood sugar monitoring [30]. By contrast, positive mental wellbeing (e.g. a positive emotional state) has been implicated in reduced diabetes risk [31]. One study found that diabetes patients exposed to group-based sessions promoting positive concepts such as empowerment and peer support reported significant HbA1c improvements after 1 year [32]. There has been limited research on ethnic differences in mental wellbeing. Some research indicates significant ethnic differentials, with Caucasians reporting higher levels of mental distress compared to South Asians, particularly in the context of diabetes [33]. However, other research suggests otherwise [34]. Given ethnic differences in HbA1c [21], and associations of these variables with mental wellbeing [31, 33], it is plausible psychological functioning partly explains HbA1c disparities across South Asians and Caucasians reported in the literature [22].

There are several important covariates to consider in this context. Suffering from long-term health conditions (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer) may affect HbA1c, depending on the number and severity of diagnosed condition(s). Risk factors implicated in diabetes and cardiovascular disease (e.g. obesity, high blood pressure) may vary across ethnic groups [6], or be associated with blood sugar levels [35]. For example, BMI (body mass index) has been found to be associated with HbA1c data [36, 37]. Socioeconomic deprivation has been associated with diabetes complications and blood sugar control [38]. Deprivation also impacts differentially across ethnic groups, with an increased diabetes-related hospital readmission risk for Caucasians (by contrast, the risk of readmission in South Asians is lower, compared with Caucasians) [8]. Thus, while South Asian diabetes patients are more likely to be hospitalised for diabetes-related complications, Caucasians seem more susceptible to the effects of deprivation, albeit the implications for blood sugar control are less clear-cut [39].

Overall, there is a need to better understand the confounding effect of positive psychological states on ethnic differences in HbA1c levels. Hitherto, no study has been found specifically investigating this topic. Thus, the investigation reported here aimed to address this gap in the literature, while adjusting for important covariates. Given evidence suggesting ethnic disparities in HbA1c, whereby South Asians show poorer outcomes [21], and given evidence associating mental wellbeing with both ethnicity [33, 34], and diabetes risk [31], it was expected that (a) ethnicity will predict HbA1c outcomes, with South Asians showing higher HbA1c levels, and (b) the association between ethnicity and HbA1c levels will be mediated by individual differences in positive mental wellbeing.

Methodology

Participants and Procedure

This study analysed data from the 2014 Health Survey for England [40]. The HSE has been conducted since 1994 and monitors health conditions and other related data (e.g. lifestyle, blood pressure, weight and height, mental wellbeing, and health service use) in UK households. Members of a household first complete a questionnaire booklet. This is followed shortly thereafter by a nurse visit, during which additional (primarily biomedical) data is collected from participants. The 2014 survey obtained data from 10,080 adults (aged 16 years and over) and children (aged up to 15 years). Data on blood sugar control (HbA1c mmol/mol results) was specifically relevant to the present study, regardless of diabetes status. A total of 3894 respondents provided valid HbA1c data. These cases, together consisted of 1987 (53.5%) women and 1729 (46.5%) men, aged 16 to 90 years (mean age = 51.68 years, SD = 17.25), with 147 (3.8%) self-identified as South Asian, and 3569 (91.7%) as Caucasian.

Measures

Ethnicity

Ethnic classifications were based on 18 groupings [41]. People who self-identified as ‘White’ (English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British), ‘White—Irish’, ‘White—Gypsy or Irish Traveller’ or ‘Any other White background’ were labelled ‘Caucasian’ (1), while respondents who identified themselves as ‘Indian’, ‘Pakistani’, or ‘Bangladeshi’ were labelled as ‘South Asian’ (0).

HbA1c Levels

HbA1c results were based on non-fasting blood samples [40]. HbA1c depicts the percentage of haemoglobin in the blood that contains glucose, over the preceding 8 to 12 weeks [19]. The HSE survey incorporated up to eight HbA1c parameters including glycated haemoglobin result (%) (blood-based data), and glycated haemoglobin result (in mmol/mol) (blood data). A HbA1c value of 6.5% (or 48 mmol/mol) is the recommended maximum cut-off beyond which diabetes may be diagnosed [16] (note: a value below 6.5%/48 mmol/mol does not completely rule out the possibility an individual has diabetes). HbA1c values below 6% (42 mmol/mol) are considered ‘normal’, while values ranging from 6 to 6.4% (42 to 47 mmol/mol) suggests pre-diabetes. From June 2009, laboratories in the UK have been reporting HbA1c results primarily in millimoles per mole rather than in percentages (%). Thus, for consistency, this study used glycated haemoglobin results calibrated in millimoles per mole as the primary outcome variable.

Mental Wellbeing

Positive mental wellbeing was the primary ‘exposure’ variable of interest, as this factor was expected to ‘explain’ (i.e. mediate) ethnic disparities in HbA1c levels. Mental wellbeing was measured using the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) [29]. Respondents are asked to read each of the 14 statements describing various feeling and thoughts, and then indicate the extent to which each item had been experienced during the past 2 weeks. Examples of items include ‘been feeling optimistic about the future’, ‘been feeling useful’, ‘been feeling relaxed’, ‘been feeling interested in other people’, ‘had energy to spare’, ‘been dealing with problems well’, ‘been thinking clearly’, and ‘been feeling good about myself’. Responses were indicated on a 5-point Likert-style scale: ‘None of the time’ (1), ‘Rarely’ (2), ‘Some of the time’ (3), ‘Often’ (4), and ‘All of the time’ (5). Responses were totaled to give a single score depicting mental wellbeing, with a higher score depicting better psychological functioning (α = 0.93). To obtain greater clarity regarding the role of specific aspects of mental wellbeing in HbA1c outcomes across ethnic groups, it was decided to treat the 14 WEMWBS domains as single-item measures [42]. The use of single-item measures is justified when (a) weak or modest effect sizes are expected (there is no previous evidence suggesting a particularly strong mediating effect of mental wellbeing on ethnicity-HbA1c relations), (b) scale items are highly homogeneous (α > 0.90) (internal consistency for the mental wellbeing items exceeded this value), (c) items are semantically redundant (due to high internal consistency), which negatively affects multiple item measures, and (d) the population is diverse (e.g. ethnic differences) [42, 43]. Moreover, the use of single-items in an ethnicity/HbA1c context may have important practical implications for health care. For example, it could enable health professionals more easily identify and address specific elements of psychological functioning implicated in elevated HbA1c levels, within a particular ethnic group. The term ‘mental wellbeing’ is arguably too broad a concept to manipulate in the context of a health education program, or routine doctor-patient consultations.

Covariates

Covariates consisted of age, gender, mental wellbeing, employment earnings, biomedical factors (diabetes status, blood pressure, body mass index/BMI) and lifestyle factors (physical activity, cigarette smoking).

Physical activity was measured using the short version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [44]. This instrument assesses physical activity across a range of domains including leisure time, yard activities (e.g. gardening), and work-related activities. The short IPAQ evaluates three activity types: walking, moderate-intensity activities, and vigorous intensity activities. Frequency (calibrated in days per week) and duration (time per day) are computed for each activity type. This data is then used to compute a total physical activity score for each respondent, for each activity type. The data was used to categorise respondents into two groups: ‘inactive, below 30 min MVPA (moderate-vigorous physical activity) per week’ (0) and ‘active, 30 min or more’ (1). Cigarette smoking was assessed using various items, including simply asking respondents to indicate the number of cigarettes they smoke per day.

Socioeconomic deprivation was based on a simple dichotomy depicting employment-related deprivation. Respondents were shown a card listing various possible sources of income, including ‘earnings from employment or self-employment’, and then asked to indicate which they received. For the purpose of this study responses to this employment-related item were coded as follows: ‘Earnings from employment or self-employment’ (1), ‘no earnings from employment or self-employment’ (0).

Several biomarkers were gauged. Blood pressure (BP) was measured using the Omron HEM 907 blood pressure monitor. The data was used to generate three distinct groups: ‘BP under 130/80’ (1), ‘BP under 140/90, but not under 130/80’ (2), ‘BP 140/90 or above’ (3). Respondents were also asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor they had high blood pressure (HBP), then dichotomised into two groups; doctor diagnosed high blood pressure (excluding pregnant), ‘yes’ (1), ‘no’ (2). Respondents also provided height and weight measurements, which were used to compute BMI scores (kg/m2), generating three groups: ‘Underweight’ (BMI < 18.5), ‘normal’ (BMI, 18.5 to <25), ‘overweight’ (BMI, 25 to <30), ‘obese’ (BMI, 30 to <40), and ‘morbidly obese’ (BMI, ≥ 40).

Diabetes status was gauged via multiple questions, including; whether respondents currently have, or have ever had diabetes; whether they had been told by a doctor that they had diabetes; and whether they had been told by a doctor/nurse that they had Type I or Type II diabetes. For the purposes of this study, diabetes status—‘case’ (1) versus ‘non-case’ (0)—was primarily based on the first item. This helped address sources of ambiguity where for example, a respondent may have had diabetes since childhood, but been unable to recall being informed about this by a doctor or nurse.

Results

Descriptive Data

Table 1 shows descriptive data for the sample. HbA1c levels were, on average, significantly higher in South Asians compared with Caucasians, albeit values fell below 6% (42 mmol/mol), and hence may be considered ‘normal’ (i.e. depicting ‘good’ blood sugar control for both ethnic groups) [16]. One hundred and eighty-one Caucasians and 15 South Asians met the HbA1c criterion for diabetes (HbA1c > 48 mmol/mol). Another 319 Caucasians and 15 South Asians fitted the HbA1c criterion for pre-diabetes (HbA1c of 42 to 47 mmol/mol). South Asians were significantly (approximately 10 years) younger, had a slightly lower BMI score, and smoked fewer cigarettes, compared with Caucasians. South Asians also reported slightly better mental wellbeing albeit this group difference wasn’t statistically significant (p = 0.054). South Asians were more likely to receive an income from employment or self-employment. Over 90% of respondents did not currently have, or had ever had, diabetes (just over 6% were diabetes cases). Nevertheless, diabetes prevalence in South Asians was nearly twice the rate in Caucasians. There were no ethnic differences in blood pressure groupings, or BP diagnosis by a doctor.

Bootstrapping

We used an SPSS bootstrapping dialogue [45, 46] to assess the direct association between ethnicity (Caucasian versus South Asian) and HbA1c levels, and the indirect relationship between these variables, mediated by the 14 mental wellbeing domains of the WEMWBS [29]. Bootstrapped sampling was set at 1000. Furthermore, effect size, Sobel normal theory test [47], and total effect data were generated. For each mediated regression model, ethnicity was specified as the ‘predictor’ (‘variable X’), HbA1c was entered as the ‘outcome’, while mental wellbeing factors were analysed as the ‘mediators’. Thus, several regression pathways were examined: the association between ethnicity and dimensions of mental wellbeing (path a), the relationships between mental wellbeing domains and HbA1c levels (path b), the direct association between ethnicity and HbA1c levels (path c), and the indirect effect of ethnicity on HbA1c scores, mediated by mental wellbeing dimensions (path a*b). Age, gender, mental wellbeing, employment earnings, biomedical factors (diabetes status, blood pressure, body mass index/BMI), and lifestyle factors (physical activity, cigarette smoking) were treated as covariates. Due to software constraints on the total number of mediator variables that can be tested simultaneously [45], each analysis was performed twice, initially using the first ten mental wellbeing domains, and then again using the last four dimensions. To reduce the probability of type 1 errors (‘false positives’), statistical significance for mediator effects was based on the conservative Sobel normal theory test [47].

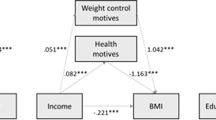

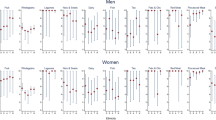

Bootstrapping revealed both direct and indirect associations (see Fig. 1) [45]. There was a significant direct association (path c) between ethnicity and HbA1c (see Table 2); Caucasians obtained lower HbA1c values compared with South Asians. Several domains of mental wellbeing also predicted HbA1c (path b); HbA1c levels were lower given greater perceived energy to spare, and higher optimism about the future, but less relaxation. Ethnicity predicted several aspects of mental wellbeing (path a), most notably perceived energy levels; Caucasians felt significantly less energetic compared to South Asians. Furthermore, the indirect effect of ethnicity on HbA1c, via perceived energy (paths a*b), was significant, based on the conservative normal theory (i.e. Sobel) test. This mediator effect accounted for 14.1% of the relationship between ethnicity and HbA1c, and is illustrated in Fig. 2; lower HbA1c levels were associated with greater perceived energy, which in turn was more typical of South Asians.

To ascertain the robustness of observed associations bootstrapping was repeated while adjusting for various covariates. Adjustment for demographic factors (age, gender, deprivation) slightly attenuated, but did not abolish the mediator effect. Furthermore, the direct association between ethnicity and HbA1c remained significant. However, the mediator effect was no longer significant after adjusting for biomedical markers, specifically BMI. Accounting for biological factors together (BMI, diabetes status, blood pressure) markedly increased the percentage of HbA1c variance explained by the total model (to 44%), but failed to negate the significant effect of ethnicity on HbA1c. All biomarkers significantly predicted HbA1c having diabetes, higher blood pressure, and a higher BMI score were associated with higher HbA1c values. Adjusting for cigarette smoking and levels of physical activity had little effect on the direct relationship between ethnicity and HbA1c.

Finally, to further explore the role of mental wellbeing in a clinical context, additional bootstrapping analysis was performed using only respondents with pre-diabetes (HbA1c of 42 to 47 mmol/mol) or diabetes (HbA1c > 48 mmol/mol). It was decided to combine the pre-diabetes and diabetes groups due to the very small number of South Asian cases. As before, bootstrapping examined the mediating effects of the 14 mental wellbeing dimensions on ethnic disparities in HbA1c values. No mediating effects emerged. Furthermore, the total effect and direct effect models were both non-significant (p > 0.05), albeit one dimension of mental wellbeing—feeling cheerful—was associated with HbA1c outcomes: more cheerful patients had significantly lower HbA1c levels.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the degree to which positive mental wellbeing affects ethnic differences in HbA1c outcomes. Some evidence for mediation emerged: perceived energy levels partly confounded the relationship between ethnicity and HbA1c levels. Furthermore, ethnicity and several positive psychological dispositions directly predicted glycaemic control. HbA1c values were lower amongst Caucasians. While some research has found no disparity between South Asians and Caucasians in HbA1c levels [12], the present findings support previous evidence indicating poorer HbA1c values in South Asians compared with Caucasians [13]. Furthermore, the current findings show that mental wellbeing concerning perceived vigour is important in understanding ethnic differences in glycaemic control.

Previous studies have found HbA1c differentials between Caucasians and South Asians [21–23]. For example, one study found higher HbA1c outcomes in the South Asians patients (6.11 ± 0.58%) compared to Caucasians (5.90 ± 0.40%) [21]. The present findings support previous observations. South Asians may experience poorer glycaemic control for a number of cultural and religious reasons, including unhealthy dietary norms, language discordance that hampers communication with health professionals, and misunderstanding and misinterpretation of self-management guidelines [14]. For example, compared to Caucasians, South Asians may derive a higher proportion of their food energy from fat and saturated fat, a situation compounded by use of unhealthy cooking methods such as deep fat frying [48]. Many South Asians consume foods considered detrimental to glycaemic control, due to a perception of such foods as ‘strength giving’, and/or strong cultural pressures to eat such foods together (e.g. with family members) [48]. There may also be a tendency to view diabetes as an inevitable act of divine intervention (e.g. ‘Gods will’), or hereditary, and/or to rely on Ayurveda and folk herbal treatments [49]. Nevertheless, it should be emphasised that South Asians are a very diverse group, both in a cultural (e.g. cooking styles) and religious (e.g. Hinduism, Islam) sense. Thus, the cultural explanations offered thus far don’t necessarily apply across subgroups. Furthermore, blood sugar control in this study was actually ‘normal’ for both ethnic groups, with HbA1c group means falling well below the cut-offs for pre-diabetes and diabetes (HbA1c < 42 mmol/mol) [16].

While previous research implicates mental wellbeing in HbA1c levels [30, 31], this is the first study to assess mental wellbeing as a mediating factor that partly accounts for ethnic differentials in HbA1c values. South Asians reported higher perceived energy levels, and this mind-set was associated with lower HbA1c levels. Thus, perceived energy may play a protective glycaemic role for South Asians, in terms of better glycaemic control and hence reduced diabetes risk. There may be cultural undertones, whereby South Asians for example enjoy the various benefits of an extended family system that help to reduce physical exhaustion (e.g. help with childcare, preparing meals, house chores). These benefits may be less available to Caucasians, assuming a predominantly nuclear family system. Having more energy could mean a greater capacity to engage in self-care behaviours critical to glycaemic control, most notably physical activity. Thus, the excess HbA1c levels in South Asians, relative to Caucasians, may be partly attributable to less perceived vigour in some South Asian individuals.

It should be noted that this mediator effect wasn’t replicated when bootstrapping was performed using only pre-diabetes and diabetes cases. Furthermore, the effect accounted for a modest proportion (<15%) of the variance in HbA1c levels. This suggests the South Asian deficit (i.e. higher HbA1c value) in blood sugar control is largely attributable to other factors, possibly unrelated to mental wellbeing, irrespective of clinical diagnosis. Moreover, the mediator effect was negated after accounting for BMI, suggesting body weight may play a key role in this context. Research suggests energy levels are related to body weight, particularly in men [50]. Body weight, in turn, has been associated with ethnic differences in diabetes risk [6]. Evidence also suggests that, compared to Caucasians, some ethnic minority groups are more susceptible to chronic fatigue syndrome, a condition typified by unexplained exhaustion [51]. Research has found that chronic fatigue is highly prevalent in both Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes sufferers [52]. However, it is unclear to what extent this condition accounts for the mediator effect observed here, especially given that Caucasians felt less energetic, and the association between chronic fatigue and HbA1c is unclear [52]. It is possible the elevated HbA1c levels amongst South Asians found here, and reported in the literature [21], should actually be higher if not for the dampening effect of greater perceived energy, which may help facilitate the performance of self-care activities essential for glycaemic control (e.g. physical activity).

Accounting for biomedical factors significantly increased the proportion of HbA1c variance explained. This is unremarkable given the strong associations between biological factors, notably BMI and diabetes status, and blood sugar control [35]. Taken together the emerging patterns suggest a plausible scenario, whereby ethnicity relates to HbA1c levels, both directly as previously reported in the literature [21–23], and indirectly through perceived energy levels. This latter observation is the most important finding from this study. While energy levels are related to body weight [53], and have physiological underpinnings, it is the perception of lack of energy that is critical here. South Asians, overall, appear to have a more positive mind-set regarding personal vivacity, with potentially favourable implications for glycaemic control.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, there was a notable reduction in sample size as each covariate (or set of covariates) was controlled for, due to missing data. Accounting for the final set of covariates (lifestyle factors) reduced the sample to just over 2911, possibly increasing the risk of type II errors. The small number of South Asian participants (relative to the number of Caucasian respondents) is a particular concern; it is possible the results may not generalise to the wider South Asian population. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the data used here is based on a representative (stratified) sample of UK families and hence may roughly reflect ethnic demographic proportions and diabetes prevalence in the general UK population [40]. Another limitation is selectivity in the covariate adjustments. Numerous biopsychosocial factors may affect HbA1c results [16]. For example, genetic characteristics, cardiovascular disease, and a range of illness-related factors have been implicated in HbA1c levels [16]. Insulin resistance has been identified as a key factor in the South Asian surplus diabetes risk [6]. Attempting to control for every conceivable covariate is impractical, so a selection of the more salient covariates was assessed here (e.g. obesity/BMI, diabetes status). Nevertheless, it is conceivable the direct effects of ethnicity observed here may be negated by uncontrolled covariates (e.g. insulin resistance). Finally, interpretation of ethnic differences may be confounded by the failure to distinguish between different South Asian communities (e.g. Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani). South Asians are a culturally and religiously diverse group [48], a diversity that extends to diabetes-related outcomes. For example, diabetes risk is significantly higher in South Asians of Indian or African Asian descent, compared to those with a Pakistani or Bangladeshi background [7].

Conclusions

This study confirms previously reported ethnic disparities in glycaemic control, with South Asians experiencing higher HbA1c outcomes compared to Caucasians. The findings build on existing literature by highlighting the mediating effect of perceived energy in this context. Hitherto previous research on ethnic differences in glycaemic control have not examined the contribution of positive mental wellbeing. The current results suggest ethnic inequalities in glycaemic control are partly explained by how energetic people perceive themselves to be, albeit this effect is modest and negated after accounting for BMI and other covariates. Perceived energy may serve a protective glycaemic function in South Asians, as this perception was associated with lower HbA1c levels, and more pronounced amongst South Asians compared to Caucasians. However, ethnic differences in HbA1c transcend biopsychosocial factors including diabetes status and were only marginally explained by the mediating effect of perceived energy. The present findings justify concerns regarding an elevated diabetes risk in South Asians relative to Caucasians. Poorer glycaemic control in the former group may be dampened by individual differences in perceived energy levels, based on the present data. This mediator effect necessitates further analysis of the possible role of conditions such as chronic fatigue syndrome in the higher HbA1c levels amongst South Asians.

References

Menzin J, Korn JR, Cohen J, Lobo F, Zhang B, Friedman M, et al. Relationship between glycemic control and diabetes-related hospital costs in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Manage Care Pharm. 2010;16:264–75.

Menke A, Rust KF, Fradkin J, Cheng YJ, Cowie CC. Associations between trends in race/ethnicity, aging, and body mass index with diabetes prevalence in the United States: a series of cross-sectional studies. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:328–35.

Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314:1021–9.

Diabetes UK. The cost of diabetes. London: Diabetes UK; 2014.

Chai TY, Tonks KT, Campbell LV. Long-term glycaemic control (HbA1c), not admission glucose, predicts hospital re-admission in diabetic patients. Australas Med J. 2015;8:189–99.

Tillin T, Hughes AD, Godsland IF, Whincup P, Forouhi NG, Welsh P, et al. Insulin resistance and truncal obesity as important determinants of the greater incidence of diabetes in Indian Asians and African Caribbeans compared with Europeans the Southall and Brent REvisited (SABRE) cohort. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:383–93.

Diabetes UK. Diabetes: facts and figures. Revised ed. London 2015.

Nishino Y, Gilmour S, Shibuya K. Inequality in diabetes-related hospital admissions in England by socioeconomic deprivation and ethnicity: facility-based cross-sectional analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116689.

Asper DE. Predicting hospital readmissions in patients with diabetes: importance of diabetes education and other factors. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2010;70:2338.

Cook CB, Naylor DB, Hentz JG, Miller WJ, Tsui C, Ziemer DC, et al. Disparities in diabetes-related hospitalizations: relationship of age, sex, and race/ethnicity with hospital discharges, lengths of stay, and direct inpatient charges. Ethnicity & disease. 2006;16:126–31.

Robbins JM, Webb DA. Hospital admission rates for a racially diverse low-income cohort of patients with diabetes: the urban diabetes study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1260–4.

Benhalima K, Wilmot E, Khunti K, Gray LJ, Lawrence I, Davies M. Type 2 diabetes in younger adults: clinical characteristics, diabetes-related complications and management of risk factors. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:57–62.

Khan H, Lasker SS, Chowdhury TA. Exploring reasons for very poor glycaemic control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes. 2011;5:251–5.

Sohal T, Sohal P, King-Shier KM, Khan NA. Barriers and facilitators for type-2 diabetes management in South Asians: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136202.

Driskell OJ, Holland D, Waldron JL, Ford C, Scargill JJ, Heald A, et al. Reduced testing frequency for glycated hemoglobin, HbA(1c), is associated with deteriorating diabetes control. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2731–7.

World Health Organisation. Use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2011.

Aroda VR, Ratner R. Approach to the patient with prediabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3259–65.

Kwon SS, Kwon JY, Park YW, Kim YH, Lim JB. HbA1c for diagnosis and prognosis of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;110:38–43.

Jia WP. Standardising HbA1c-based diabetes diagnosis: opportunities and challenges. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2016;16:343–55.

Oldfield MD, Donley P, Walwyn L, Scudamore I, Gregory R. Long term prognosis of women with gestational diabetes in a multiethnic population. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:426–30.

Likhari T, Gama R. Ethnic differences in glycated haemoglobin between white subjects and those of South Asian origin with normal glucose tolerance. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:278–80.

Shipman KE, Jawad M, Sullivan KM, Ford C, Gama R. Ethnic/racial determinants of glycemic markers in a UK sample. Acta Diabetol. 2015;52:687–92.

Whincup PH, Nightingale CM, Owen CG, Rudnicka AR, Gibb I, McKay CM, et al. Early emergence of ethnic differences in type 2 diabetes precursors in the UK: the child heart and health study in England (CHASE study). PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000263.

Aujla N, Davies MJ, Skinner TC, Gray LJ, Webb DR, Srinivasan B, et al. The association between anxiety and measures of glycaemia in a population-based diabetes screening programme. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2011;28:785–8.

James GD, Baker P, Badrick E, Mathur R, Hull S, Robson J. Ethnic and social disparity in glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; cohort study in general practice 2004–9. J R Soc Med. 2012;105:300–8.

Cooke D, Bond R, Lawton J, Rankin D, Heller S, Clark M, et al. Modeling predictors of changes in glycemic control and diabetes-specific quality of life amongst adults with type 1 diabetes 1 year after structured education in flexible, intensive insulin therapy. J Behav Med. 2015;38:817–29.

Camara A, Balde NM, Enoru S, Bangoura JS, Sobngwi E, Bonnet F. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among diabetic African patients in Guinea: association with HbA1c levels. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41:62–8.

Strandberg RB, Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Peyrot M, Rokne B. Relationships of diabetes-specific emotional distress, depression, anxiety, and overall well-being with HbA1c in adult persons with type 1 diabetes. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:174–9.

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:63.

Pearson S, Nash T, Ireland V. Depression symptoms in people with diabetes attending outpatient podiatry clinics for the treatment of foot ulcers. J Foot Ankle Res. 2014;7.

Tsenkova VK, Karlamangla AS, Ryff CD. Parental history of diabetes, positive affect, and diabetes risk in adults: findings from MIDUS. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2016.

Due-Christensen M, Hommel E, Ridderstrale M. Potential positive impact of group-based diabetes dialogue meetings on diabetes distress and glucose control in people with type 1 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2016.

Ali S, Davies MJ, Taub NA, Stone MA, Khunti K. Prevalence of diagnosed depression in South Asian and white European people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a UK secondary care population. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:238–43.

Aujla N, Abrams KR, Davies MJ, Taub N, Skinner TC, Khunti K. The prevalence of depression in white-European and South-Asian people with impaired glucose regulation and screen-detected type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7755.

Paul S, Best J, Klein K, Han J, Maggs D. Effects of HbA1c and weight reduction on blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with exenatide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:826–34.

Watson L, Wilson BP, Alsop J, Kumar S. Weight and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes: what is the outcome of insulin initiation? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:823–31.

Tsenkova VK, Carr D, Schoeller DA, Ryff CD. Perceived weight discrimination amplifies the link between central adiposity and nondiabetic glycemic control (HbA(1c)). Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:243–51.

Bihan H, Laurent S, Sass C, Nguyen G, Huot C, Moulin JJ, et al. Association among individual deprivation, glycemic control and diabetes complications—the EPICES score. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2680–5.

O'Kane MJ, McMenamin M, Bunting BP, Moore A, Coates VE. The relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and metabolic/cardiovascular risk factors in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prim Care Diabetes. 2010;4:241–9.

Health Survey for England. Methods and documentation. Leeds: NatCen Social Research, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL; 2014.

Health Survey for England. Methods and documentation. In: Health, editor. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2013. p. 208.

Diamantopoulos A, Sarstedt M, Fuchs C, Wilczynski P, Kaiser S. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. J Acad Market Sci. 2012;40:434–49.

Fuchs C, Diamantopoulos A. Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research. Business Administration Review. 2009;69:195–210.

Booth M. Assessment of physical activity: an international perspective. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2000;71(Suppl 2):114–20.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013.

Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr. 2009;76:408–20.

Mackinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivar Behav Res. 1995;30:41–62.

Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hanna L, Douglas M, Bains H, Hallowell N. We should change ourselves, but we can’t: accounts of food and eating practices amongst British Pakistanis and Indians with type 2 diabetes. Ethnic Health. 2008;13:305–19.

Joseph LM, Berry D, Jessup A. Management of type 2 diabetes in Asian Indians: a review of the literature. Clin Nurs Res. 2015;24:188–210.

Schur EA, Noonan C, Smith WR, Goldberg J, Buchwald D. Body mass index and fatigue severity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 2007;14:69–77.

Dinos S, Khoshaba B, Ashby D, White PD, Nazroo J, Wessely S, et al. A systematic review of chronic fatigue, its syndromes and ethnicity: prevalence, severity, co-morbidity and coping. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1554–70.

Goedendorp MM, Tack CJ, Steggink E, Bloot L, Bazelmans E, Knoop H. Chronic fatigue in type 1 diabetes: highly prevalent but not explained by hyperglycemia or glucose variability. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:73–80.

Saydah S, Bullard KM, Cheng YL, Ali MK, Gregg EW, Geiss L, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors by obesity level in adults in the United States, NHANES 1999–2010. Obesity. 2014;22:1888–95.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Key Points

1) Previous research has shown significant differences in HbA1c levels between South Asian and Caucasian UK residents. However, it remains unclear the extent to which these differences are explained by positive mental wellbeing.

2) Analysis of population-based data from the Health Survey for England showed that individual differences in a specific aspect of positive mental wellbeing—perceived energy level—partly confounded the ethnic disparity in HbA1c levels

3) South Asians felt more energetic than Caucasians, which in turn was associated with lower HbA1c levels. Thus, perceived lack of fatigue may serve a protective glycaemic function in South Asians.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Umeh, K. Are Ethnic Disparities in HbA1c Levels Explained by Mental Wellbeing? Analysis of Population-Based Data from the Health Survey for England. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 86–95 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0346-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0346-0