Abstract

The application of LCL filters has become popular for inverters connected to the power grid due to their advantages in harmonic current reductions. However, the power grid in a distribution system is non-ideal, presenting itself as a voltage source with significant impedance. This means that an inverter using an LCL filter may interact with other grid-connected inverters via the non-ideal grid. In this paper, damping optimization of LCL filters to reduce this interaction is studied for a three-phase voltage source inverter (VSI). Simulation results show that resonant oscillation occurs in a distributed power grid, even if the VSI with an LCL filter is well designed for standalone applications. A small-signal analysis is performed to predict this stability problem and to locate the boundary of the instability using an impedance approach. Based on these analytical results, optimized damping of the LCL filter can be designed. The oscillation phenomena and optimized damping design are verified by simulations and experimental measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Distributed generation, which is able to collect energy from multiple sources, has lower environmental impact and improved security of supply compared to centralized generation and transmission. Local power production has short distance power transmission, and reduces the dependence on the infrastructure of large power plants on the supply side, and distribution systems on the demand side. Renewable energy sources, such as solar power and wind power, and storage devices are connected to the distributed power grid through different kinds of power converters. One of the candidate power converters is the three-phase voltage source converter, which can work in regenerative mode and serve as a three-phase voltage source inverter (VSI) [1].

A filter with two series inductors and a shunt capacitor (an LCL filter) is usually applied to reduce the current harmonics around the switching frequency, because it can achieve good attenuation of the high frequency switching noise by using reasonably small passive filtering devices. One key consideration of the filter is its damping design, since the LCL filter suffers from instability due to the zero impedance at its resonant frequency [2,3,4]. Passive damping is a practical choice because it costs little and requires no additional control. A damping resistor is inserted in series with the filter capacitor, and a larger damping resistor gives more effective damping. However, it reduces the attenuation above the resonant frequency and also causes power loss at low frequencies. Therefore, there are always some tradeoffs in LCL filter design.

Research has been carried out towards better damping and design criteria for LCL filters. For passive damping design, although it is simple, there has been much discussion in the literature about its tradeoffs for different applications. In [5], the criterion for choosing the passive damping resistor is developed considering power loss and stability. In [6], the resistance value is chosen to be one-third of the impedance of the filter capacitor at the resonant frequency, which may not always be suitable for different situations. In [7], the passive damping parameter is chosen by a trial-and-error method according to Bode plots. In [8], two selective damping solutions, described as selective low-pass damping and selective resonant damping, are proposed according to different passive damping circuits. In [9], split-capacitor resistive passive damping is analysed for applications of several tens of kilowatts. In [10], the split-capacitor resistive inductive passive damping method for LCL filters in grid-connected inverters is proposed based on a complex connection of the passive elements.

Active damping is a more efficient and flexible way to manage the instability of LCL filters at resonance. Much literature has discussed various compensation methods for active damping. In [11], generalized design of LCL filters for shunt active power is discussed. It takes into account the main design features, including selection of LCL parameters, interactions between resonant damping and harmonic compensation and bandwidth design of the closed-loop system. In [12], capacitor current feedback active damping is proposed and a guideline for choosing the LCL filter’s resonant frequency is given. Reference [13] proposes highly accurate design of LCL filter parameters based on the grid impedance. Reference [14] considers multiple grid-connected converters. The contribution of each converter to the harmonic stability of the power system can be predicted by Nyquist diagrams. Various active damping methods can also be found in [15,16,17,18,19,20,21] and most discuss system design from control point of view, ignoring the inherent damping characteristic of the filter.

When other power converters are connected to the distributed power grid, the overall system structure is changed [22]. Operation of a converter with an LCL filter might be affected through the inductive non-ideal grid, thus even well-designed damping might be insufficient for the whole interacted system, leading to further instability [23]. The design criteria for LCL filters when there are multiple grid-connected converters are still not well developed. These interacting inverters are typically represented by a voltage source inverter with an L filter, which may affect the system response and interact with the existing three-phase VSI [24]. Therefore, damping design under such non-ideal grid conditions should be re-considered.

This paper investigates the kind of interaction which is caused by improper design of the damping resistor. The differences between the passive damping resistor for uncoupled and coupled situations are discussed. Design considerations are proposed for the choice of passive damping resistor in an interacting system, especially in a power system with multiple inverters connected to a non-ideal power grid. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 shows the instability phenomena when a VSI with well-designed passive damping is connected to the power grid along with other inverters. Section 3 gives a detailed stability assessment employing an impedance-based approach. In Sect. 4, we present our results in a design-oriented format to explain how variation of selected parameters would affect stability. These results will facilitate the choice of parameters for stable operation. Section 5 highlights the instability phenomena caused by improper design of damping resistor. Section 6 concludes this paper.

2 System instability

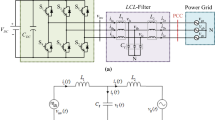

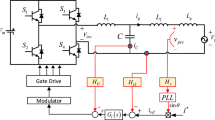

Instability caused by the interaction of voltage source inverters (VSIs) will be shown in this section. A two-level voltage source inverter topology is adopted in this study and a d-q decoupled dual-loop control for bi-directional power flow is applied, as shown in Fig. 1. Two types of VSI may be connected to the distributed power grid at the same time. The whole system is set up as a MATLAB Simulink simulation. The parameters of the system used in the simulations are summarized in Table 1.

Inverters with either an L or an LCL filter are individually stable. The passive damping resistor is optimized at 1.5 Ω. Then, another inverter with an L filter, which is also stable individually, is connected to the point of common coupling (PCC) at 0.25 s. However, when these two inverters are concurrently connected to the non-ideal power grid at the PCC, the output currents and their voltages have a high harmonic content.

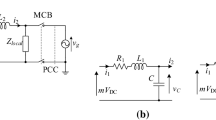

Figure 2 shows an enlarged graph of the harmonic oscillation. Harmonic oscillation frequency around 1 kHz emerges in the grid current. Since the AC grid has internal impedance, the grid voltage at the PCC gets distorted, as the blue waveforms in the figure show.

Thus, it can be inferred that the inverters could interact with each other and lose stability when connected to the non-ideal power grid, even though the values of parameters are individually selected within the stability region for each converter.

Furthermore, the passive damping resistor is optimized for the inverter with an LCL filter. The value of the resistor is chosen to give enough damping while avoiding excessive ohmic losses. However, it can be seen that a problem arises when it is connected to the distributed grid with other inverters simultaneously. The inverter with a damped LCL filter still interacts with the non-ideal power grid, since the whole system structure is changed. The primary cause of this mid-frequency oscillation will be analyzed in Sect. 3.

3 Analysis of interaction

Firstly, two VSIs will be studied individually. Then, the impedance-based approach will be used to study interacting inverters connected to a non-ideal power grid.

3.1 Analysis of uncoupled system

The formulation for a grid-connected three-phase voltage source inverter with an L filter will be based on the configuration shown in Fig. 1a. The grid impedance (inductive) and the positive current direction of the system is shown in the figure. Therefore, the VSI with L filter can be described in the d-q reference frame as:

v sd,q , and i d,q are the AC voltages and currents expressed in the d-q reference frame at the PCC. For simplicity, we ignore the inductor resistance R s in the following analysis.

From these differential equations, we can obtain the small signal representation via the usual linearization procedure:

where the capitalized variables are the steady-state values of the system, given by: \(D_{d} = \frac{{2V_{sd} }}{{V_{dc} }},\;D_{q} = - \frac{{2\omega LI_{d} }}{{V_{dc} }}\), I d = I dref and I q = 0.

The linearized small-signal equations in the time domain can be transformed into the frequency domain. The state-space representation of the closed-loop system can be obtained as:

where \(\varvec{T}_L (s) = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} {\frac{{g_{i} }}{L}} \hfill & 0 \hfill & {\frac{{D_{d} }}{2L}} \hfill \\ 0 \hfill & {\frac{{g_{i} }}{L}} \hfill & {\frac{{D_{q} }}{2L}} \hfill \\ { - \frac{3}{2}\frac{{D_{d} }}{C} - \frac{{3g_{i} I_{d} }}{{CV_{dc} }}} \hfill & { - \frac{3}{2}\frac{{D_{q} }}{C} - \frac{{3\omega LI_{d} }}{{CV_{dc} }}} \hfill & 0 \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{B}_L = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} { - \frac{1}{L}} & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & { - \frac{1}{L}} & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & { - \frac{1}{C}} \\ \end{array} } \right]\), and g i is the current loop PI control function g i = k ip + k ii /s.

Here, since the VSI is working in regenerative mode, instability in the AC current will mainly be triggered by the inner current control loop. The outer voltage loop is therefore ignored in this analysis. For brevity of presentation, we define that: \(\varvec{I} = \left[ \begin{aligned} i_{d} (s) \hfill \\ i_{q} (s) \hfill \\ \end{aligned} \right],\;\varvec{V} = \left[ \begin{aligned} v_{d} (s) \hfill \\ v_{q} (s) \hfill \\ \end{aligned} \right],\;\varvec{Y} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} { - \frac{1}{L}} & 0 \\ 0 & { - \frac{1}{L}} \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{G}_{i}= \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\frac{{g_{i} }}{L}} & 0 \\ 0 & {\frac{{g_{i} }}{L}} \\ \end{array} } \right],\;\varvec{A}_{i} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\frac{{D_{d} }}{2L}} \\ {\frac{{D_{q} }}{2L}} \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{A}_{v} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} { - \frac{3}{2}\frac{{D_{d} }}{C} - \frac{{3g_{i} I_{d} }}{{CV_{dc} }}} & { - \frac{3}{2}\frac{{D_{q} }}{C} - \frac{{3\omega LI_{d} }}{{CV_{dc} }}} \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{T}_{L} \varvec{ = }\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\varvec{G}_{i} } &{\varvec{A}_{i} } \\ {\varvec{A}_{v} } & {0} \\ \end{array} } \right]\) and \(Z_{o} = - \frac{1}{C}\). The state-space equations of the VSI with closed-loop control can be written in impedance form, i.e.,

where A is an unit matrix. Therefore, the characteristic polynomial that determines the stability of the closed-loop system is:

The three-phase VSI with LCL filter can be modelled in a similar manner, as shown in Appendix A. However, since the additional inductors and capacitors are inserted in the filter, the VSI with LCL filter is a seventh-order system.

Whether the VSI uses an L filter or an LCL filter, its characteristic polynomial can be found according to (5), and we can assess the stability of the system by inspecting the roots of Φ CL (s) = 0, i.e., the eigenvalues of T ( s ). All eigenvalues should have negative real parts to ensure system stability. Using the circuit parameters in Table 1, the eigenvalues of the independently operated inverters with L and LCL filters can be calculated as given in Table 2, indicating stable operation of the uncoupled inverters.

3.2 Analysis of interacting inverters

The foregoing subsection derives the conventional inverter’s closed-loop control model and assesses the stability of the inverters when working independently (uncoupled). In this subsection, the inverters are connected to the power grid at a common coupling point and thus interact with each other. Firstly, starting with (4), we can derive the impedance of the inverter with an L filter from:

Combining (6) and i dc = v dc /r dc , we can obtain the input admittance of the VSI with an L filter as seen at the coupling point:

Then, we can assume that the VSI with an LCL filter is equivalent to the VSI with an L filter which is series-parallel connected with L, C and R d . Thus its admittance is

where \(\varvec{Y}_{{1}} = \frac{{Y_{c} }}{{1 + Y_{c} R_{d} }}\), \(\varvec{Y}_{{c}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {sC_{1} } & { - \omega C_{1} } \\ {\omega C_{1} } & {sC_{1} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{Z}_{{1}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {sL_{1} } & { - \omega L_{1} } \\ {\omega L_{1} } & {sL_{1} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\), \(\varvec{Y}_{{{L2}}}^{{{CL}}} \varvec{ = Y}_{{2}}^{{{CL}}} \varvec{ + }\frac{{\varvec{B}_i^{CL} \varvec{B}_v^{{CL}} }}{{R - Z_{o}^{CL} }}\).

Therefore, the total input admittance of the two inverters can be found as:

The grid impedance is also transformed into the d-q frame, and is written as:

where \(\varvec{I}_{{g}} = \left[ \begin{aligned} I_{gd} \hfill \\ I_{gq} \hfill \\ \end{aligned} \right]\), \(\varvec{V}_{{g}} = \left[ \begin{aligned} V_{gd} \hfill \\ V_{gq} \hfill \\ \end{aligned} \right]\), \(\varvec{Z}_{{g}} = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {sL_{g} } & { - \omega L_{g} } \\ {\omega L_{g} } & {sL_{g} } \\ \end{array} } \right]\).

Based on this small signal model, the grid current I g from inverters to the power grid can be expressed as:

Since the inverters are stable when operating independently, both Y ( s ) and V g are stable and the stability of the combined system can be assessed by applying Nyquist criterion [27] and calculating the roots of det(A + Y ( s ) Z g ) = 0. The resulting eigenvalues are shown in Table 3, which clearly demonstrates that the interacting inverters can be unstable while the separately operated inverters are individually stable.

4 Design curves obtained by simulation

The above analysis shows that well-designed passive damping for inverters with L or LCL filters is not sufficient to avoid oscillation when two or more inverters interact with each other. In this section, we will use time-domain simulation to identify the difference of passive damping between the LCL filter and interacting inverters.

Firstly, the critical R d values for independent and uncoupled inverter are compared. The values are found through simulation with current loop gain k p = 30 as an example. The red curve in Fig. 3 is the boundary of stable operation of an independent inverter with an LCL filter. The resonance peak of the LCL filter can be well damped by a small resistor of about 1~3 Ω, depending on the grid impedance conditions. A larger value of R d can ensure the stable operation of the inverter with an LCL filter. When the grid impedance increases, the damping resistor should be slightly increased to give enough margin for system stability.

However, for coupled inverters, the stability region shrinks dramatically. In Fig. 3, the boundary of stable operation moves up to the blue curve. This indicates that a larger damping resistor is needed for the LCL filter in the coupled situation. For instance, R d = 1 Ω gives enough damping for a single inverter with an LCL filter, when the grid impedance L g = 0.7 mH. But when it is connected to another inverter in parallel, the system becomes unstable, with the behavior shown in Fig. 2. The critical damping resistor values are listed in Table 4, for different grid impedances L g .

Secondly, the critical value of R d for different power ratings is examined. Here, it is assumed that the grid impedance is fixed at L g = 0.6 mH. The red curve of Fig. 4 is the boundary of stable operation of an independent inverter with an LCL filter. For higher power rating, a larger damping resistor is needed for LCL filter to ensure enough stability margin for the inverter.

For coupled inverters, if the inverter with an LCL filter is connected in parallel with an inverter with an L filter, the stability region is affected by their interaction, and the system needs more effective damping. Therefore, a much larger damping resistor, as shown in the blue curve, is adopted to ensure the stable operation of the whole system. In this simulation, the power rating of the inverter with an L filter is fixed at 4 kW.

Therefore, in the case of coupled inverters, the damping resistor R d usually should be larger than that in a single inverter. A larger R d gives more stability margin for the whole system. Especially, for a weak grid, the interaction of inverters will be significant as the grid impedance L g is high. The system is more prone to oscillation in this case. As a tradeoff, a larger passive damping resistor R d should be adopted to give enough stability margin, even though it will cause more power loss. The optimized values of R d for a weak grid are listed in Table 5.

In the foregoing analysis, the system’s stability can be determined precisely by the impedance-based approach in Sect. 3. However, for engineering design purposes, it is more important to identify the system key parameters and how these parameters may affect the stability region of the whole system. The stability boundaries can be generated by simulations and these can be used as practical design curves. Using time-domain simulations, the influence of key parameters on stability are shown in Fig. 5, through a set of graphs that can be used as practical design curves. This analysis verifies the analytical results in Sect. 3.

The effects of variation of different parameters on the overall system stability are summarized qualitatively in Table 6. The “+” signs indicate the increasing values of the parameters, and the arrow signs indicate whether the overall system stability margin is increased or decreased.

5 Experimental verification

The instability modelled above has been verified experimentally in the laboratory with two prototype three-phase voltage source inverters. FF225R12ME3 IGBTs manufactured by Infenion are used as switching devices, and the switching frequency is 12.8 kHz. The control of the inverter is implemented on ARM and FPGA controllers. One inverter uses an L filter and the other an LCL filter. The two inverters are connected in parallel to the 110 Vrms utility grid via reactors that represent the grid impedance. The DC input of the inverter is 360 V, with a power rating of about 2 kW for each inverter.

Figures 6, 7 and 8 show the experimental results on the prototype. In these figures, the orange curve represents the grid voltage at PCC, and the cyan curve represents the grid current of the converters feeding back to the grid. In order to show the relationship of the oscillation on grid current and voltage, the current phase is shifted by 180°. When the inverter is working independently, the resonance peak is well damped by the damping resistor of R d = 0.1 Ω in the LCL filter. The grid current is sinusoidal with small total harmonic distortion (THD), as shown in Fig. 6.

When the two inverters are connected in parallel, their grid currents are summed, as can be seen in Fig. 7a, which has approximately twice the current amplitude of Fig. 6. An unstable waveform can be seen for both the total grid current and the voltage at the PCC. Therefore, although the LCL filter is well damped for the stand-alone inverter, the system of parallel inverters is unstable with the same set of circuit parameters. Figure 7b shows an enlarged view of the unstable waveform. It can be seen that the voltage and current are oscillating at around 2.5 kHz. Therefore, the LCL filter is not well damped for this application. The system is unstable and has a high risk of oscillating to the point of divergence.

In Fig. 8, the damping resistor of LCL filter has been increased to R d = 1 Ω. It can be seen that the parallel connected system operates with more stability under this condition.

The experimental results show that although an inverter with an LCL filter can be designed for stable stand-alone operation, even in non-ideal grid conditions, there is still a risk of instability when two inverters are interacting through a weak grid. Based on the analysis in Sect. 3, the damping resistor can be optimized for this kind of applications, so that inserting a relative large value of damping resistor ensures stability for parallel connected inverters.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, the design consideration for passive damping of LCL filters in three-phase voltage source inverters is discussed under the assumption of a non-ideal distributed power grid. Our study shows that a well-designed inverter with an LCL filter interacts with other grid-connected inverters through the non-ideal grid. The cause of instability is that the impedance seen at the point of common coupling is changed by the LCL filter and the damping resistor. The emergence of instability can be identified theoretically from the roots of the characteristic equation of the inverter’s closed-loop control model. The system can be unstable, with a high harmonic content appearing in the grid current and, consequently, in the voltage at the point of common coupling. The phenomenon is verified by simulations and experiments with two prototype inverters. The key parameters that affect the stability of the coupled inverters are studied and graphed to provide practical design guidelines.

References

Li Y, Nejabatkhah F (2014) Overview of control, integration and energy management of microgrids. J Mod Power Syst Clean Energy 2:212–222. doi:10.1007/s40565-014-0063-1

Chen C, Xiong J, Wan Z et al (2016) A time delay compensation method based on area equivalence for active damping of an LCL-type converter. IEEE Trans Power Electron 32(1):762–772

Shuai Z, Hu Y, Peng Y et al (2017) Dynamic stability analysis of synchronverter-dominated microgrid based on bifurcation theory. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 99:1–1

Zamani M, Yazdani A, Sidhu TS (2012) A control strategy for enhanced operation of inverter-based microgrids under transient disturbances and network faults. IEEE Trans Power Deliv 27(4):1737–1747

Jalili K, Bernet S (2009) Design of LCL filters of active-front-end two-level voltage-source converters. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 56(5):1674–1689

Luiz ASA, Filho BJC (2008) Analysis of passive filters for high power three-level rectifiers. In: 2008 34th annual conference of IEEE industrial electronics, Orlando, FL, USA, 10–13 Nov. 2008, pp 3207–3212

Petterson S, Salo M, Tuusa H (2006) Applying an LCL-filter to a four-wire active power filter. In: 2006 37th IEEE power electronics specialists conference, Jeju, South Korea, 18–22 June 2006, pp 1–7

Liserre M, Blaabjerh F, Hansen S (2005) Design and control of an LCL-filter-based three-phase active rectifier. IEEE Trans Industr Appl 41(5):1281–1291

Channegowda P, John V (2010) Filter optimization for grid interactive voltage source inverters. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 57(12):4106–4114

Balasubramanian AK, John V (2013) Analysis and design of split-capacitor resistive inductive passive damping for LCL filters in grid-connected inverters. IET Power Electron 6(9):1822–1832

Tang Y, Loh PC, Wang P et al (2012) Generalized design of high performance shunt active power filter with output LCL filter. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 59(3):1443–1452

Wang X, Ruan X, Liu S et al (2010) Full feedforward of grid voltage for grid-connected inverter with LCL filter to suppress current distortion due to grid voltage harmonics. IEEE Trans Power Electron 25(12):3119–3127

Xin Z, Loh PC, Wang X et al (2016) Highly accurate derivatives for LCL-filtered grid converter with capacitor voltage active damping. IEEE Trans Power Electron 31(5):3612–3625

Wang X, Blaabjerg F, Loh PC (2015) Virtual RC damping of LCL-filtered voltage source converters with extended selective harmonic compensation. IEEE Trans Power Electron 30(9):4726–4737

Busada CA, Jorge SG, Solsona JA (2015) Full-state feedback equivalent controller for active damping in -filtered grid-connected inverters using a reduced number of sensors. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 62(10):5993–6002

Guo X, Zhang X, Wang B et al (2014) Asymmetrical grid fault ride-through strategy of three-phase grid-connected inverter considering network impedance impact in low-voltage grid. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29(3):1064–1068

Wang X, Blaabjerg F, Wu W (2014) Modeling and analysis of harmonic stability in an ac power-electronics-based power system. IEEE Trans Power Electron 29(12):6421–6432

Jeong H, Lee K, Choi S et al (2010) Performance improvement of LCL-filter-based grid-connected inverters using PQR power transformation. IEEE Trans Power Electron 25(5):1320–1330

Wang T, Ye Z, Sinha G, et al (2003) Output filter design for a grid-interconnected three-phase inverter. In: IEEE 34th annual power electronics specialist conference, Acapulco, Mexico, 15–19 June 2003, pp 779–784

Muhlethaler J, Schweizer M, Blattmann R et al (2013) Optimal design of LCL harmonic filters for three-phase PFC rectifiers. IEEE Trans Power Electron 28(7):3114–3125

Rockhill A, Liserre M, Teodorescu R et al (2011) Grid-filter design for a multimegawatt medium-voltage voltage-source inverter. IEEE Trans Industr Electron 58(4):1205–1217

Huang M, Tse CK, Wong S et al (2013) Low-frequency Hopf bifurcation and its effects on stability margin in three-phase PFC power supplies connected to non-ideal power grid. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst I Regul Pap 60(12):3328–3340

Peng Y, Huang M, Sun J, et al (2014) Design consideration of LCL-filter for three-phase voltage source inverter in distributed power grid. In: International power electronics and application conference and exposition (PEAC), Shanghai, China, pp 114–119

Wan C, Huang M, Tse CK et al (2015) Effects of interaction of power converters coupled via power grid: a design-oriented study. IEEE Trans Power Electron 30(7):3589–3600

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51507118), and by Open Fund of State Key Laboratory of Operation and Control of Renewable Energy and Storage Systems, China Electric Power Research Institute (Research on renewable energy power generation grid-connected converter fault tolerance evaluation method.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Cross Check Date: 22 March 2017

Appendix A

Appendix A

The model of three-phase voltage source inverter with an LCL filter shown in Fig. 1b can be obtained in the same way as for the VSI with L filter. The state equations are:

where v sd,q and i d,q are the AC voltages and currents expressed in the d-q reference frame at the PCC, and ω = 2πf.

The steady-state values of the system can be found from the state equation as follows: I 1d = I 2d − ωC 1 V cq , I 1q = ωC 1 V cd , I 2d = I 2d,ref , \(V_{cd} = \frac{{V_{d} - \frac{{\omega^{2} R_{d} L_{1} C_{1} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} C_{1} L_{1} }}I_{2d} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} L_{1} C + \frac{{\omega^{2} R_{d}^{2} C_{1}^{2} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} C_{1} L_{1} }}}}\), \(V_{cq} = \frac{{ - \omega L_{1} I_{2d} - \frac{{\omega R_{d} C_{1} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} L_{1} C_{1} }}V_{d} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} L_{1} C + \frac{{\omega^{2} R_{d}^{2} C_{1}^{2} }}{{1 - \omega^{2} L_{1} C_{1} }}}}\), \(D_{d} = \frac{{V_{cd} - \omega R_{d} C_{1} V_{cq} }}{{\frac{1}{2}V_{dc} }}\), \(D_{q} = \frac{{V_{cq} - \omega L_{2} I_{2d} + \omega R_{d} C_{1} V_{cd} }}{{\frac{1}{2}V_{dc} }}\).

The small-signal representation of the VSI with an LCL filter around its steady-state operating point can be written as:

This may be transformed to the frequency domain as:

where the T LCL and B LCL can be written as:

and

Finally, the state-space equations of the closed loop controlled VSI with an LCL filter can be written in impedance form:

The characteristic polynomial that determines the stability of the closed-loop system can be found through (5) in Sect. 3.1. The calculated results are given in Table 2 in Sect. 3.1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, M., Sun, J., Peng, Y. et al. Optimized damping for LCL filters in three-phase voltage source inverters coupled by power grid. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 5, 642–651 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-017-0298-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40565-017-0298-8