Abstract

Peer-to-peer accommodation has generated an ecosystem of platforms with different business models (i.e., for-profit and nonprofit). This study aims to identify and compare attributes that influence guests’ experiences as reviewed on the for-profit platform Airbnb and the nonprofit platforms Couchsurfing.com and HomeExchange.com according to a three-dimensional experience theoretical model and a methodological approach to interpret these attributes. The study used text-mining techniques to analyze 772,768 online travel reviews representing Spain’s four most-visited cities. Findings show that attributes influencing guests’ experiences in the case of nonprofit platforms relate to the authenticity dimension of experience (e.g., existential values and travel philosophy). Furthermore, guests reported that their guest–host interaction was the most representative attribute and that, unlike with Airbnb, such interaction helped to create a more authentic experience. By contrast, attributes of guests’ experiences in the case of for-profit platforms related to the physical amenities and characteristics that guests would expect to find in hotels. Those results can allow destination managers and accommodation practitioners to better understand users of peer-to-peer accommodations and thereby design more suitable strategies and experiences for them.

Impact statement

Experience is at the heart of the tourism industry. Until now, most research on users? experiences in Peer to Peer (P2P) accommodations has examined the for-profit platform Airbnb, which tends to be similar to experiences in traditional accommodations. Consequently, evidence of guests? experiences from other types of P2P accommodation platforms remains limited, which complicates identifying the impact of accommodation sharing at destinations and the dynamics generated based on perceptions of users? experiences. This article thus provides researchers and practitioners with insights into theory and methodologies that can elucidate the guest experience in accommodations on nonprofit accommodation platforms. Such insights can support strategies to improve the experiences of backpackers and families alike, which stands to increase their loyalty and satisfaction. According to our findings, such guests are especially interesting for destinations and provide added value, co-create more authentic experiences through host?guest interaction, and are potentially more sustainable given their P2P travel philosophy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Airbnb is the most-studied for-profit accommodation sharing platform in academic research, largely due to its influence on the tourism sector (Medina-Hernandez et al. 2020). On for-profit accommodation sharing platforms, hosts list their houses or private rooms for guests to rent via the platform, and guests pay a fee for the service, also via the platform. Although some authors have considered Airbnb to be part of the sharing economy, as a for-profit platform Airbnb has also attracted critical attention from other authors who view the platform as hardly representing a sharing economy model due to its capitalist practices (Murillo et al. 2017). Botsman and Rogers (2010) have suggested that the sharing economy enables a move from a culture in which users own assets toward a culture in which they share assets. In that scenario, the debate focuses on platforms that involve monetary exchange, including Airbnb, and their alleged contradiction with the concept of sharing itself. Dolnicar (2020) has argued that Airbnb’s paid model cannot be viewed as being either “sharing” or “collaborative,” as in “sharing economy” and “collaborative consumption,” but is more accurately classified as “paid online peer-to-peer [P2P] accommodation trading” because it offers a space where noncommercial partners trade goods and services on a digital platform. On that count, Perren and Kozinets (2018) have proposed the concept of the lateral exchange market to characterize platforms such as Airbnb as markets in which actors in a network, who are not necessarily peers and may be professionals or not, use intermediary technology to exchange assets. Some authors have claimed that, beyond Airbnb, other accommodation sharing models, including those followed by nonprofit accommodation sharing platforms, better adhere to the concept of accommodation sharing (Medina-Hernandez et al. 2020). Using those platforms, guests stay in their hosts’ homes without having to pay any fee for the accommodation, and, as many authors have shown, users of such platforms primarily seek experiences, not merely accommodations (Wirtz et al. 2019).

According to Pine and Gilmore (1999), consumers have shifted from participating in an economy of only products and services to the experience economy and, beyond looking for quality products and services, now also seek memorable experiences. When it comes to tourism, the accommodation experience is an important part of tourists’ satisfaction not only with their trips but also with the destinations (Wight 1998; Yang et al. 2019). Indeed, some researchers have argued that experience is “at the heart of the tourism industry” (Shi et al. 2019). Tourists’ experiences are aligned with their behavior, satisfaction, and intent to recommend destinations. Travelers want memorable experiences (Guttentag 2015), and accommodation sharing platforms have helped to construct such experiences (Lalicic et al. 2021). Most travelers use P2P accommodation platforms to access authentic local experiences, save money, and/or contribute to a more sustainable world, all of which are premises of the sharing economy. To date, most research on experiences with accommodation sharing has been based on Airbnb, and researchers have not only studied guests’ experiences with the hosting service, their emotional experiences in a specific context, and the experiential nature of home-sharing but also compared the accommodation sharing experience with the traditional accommodation experience (Brochado et al. 2017; Kastenholz et al. 2018; Shi et al. 2019; Guo et al. 2019). However, as some researchers have claimed, Airbnb can no longer contribute to such experiences due to becoming more of an “on-demand” platform than a sharing economy platform (Dolnicar 2020). In the typology of lateral exchange markets (Perren and Kozinets 2018), for-profit platforms such as Airbnb can be regarded as “matchmakers,” which mediate service provision between providers and consumers and offering high levels of intermediation and low levels of consociality.

By contrast, nonprofit platforms can be viewed as “forums” that connect actors and facilitate the flow of services while providing high consociality. Unlike Airbnb, nonprofit P2P platforms are digital platforms that facilitate the exchange of accommodations and/or lodging services without the primary aim of generating a profit. Those platforms often focus on providing a space for individuals to share their living spaces, offer hospitality, and/or provide lodging without having a monetary transaction as a central goal. Among them, the nonprofit sharing platform Couchsurfing has more than 15 million users of, and the nonprofit accommodation sharing platform HomeExchange has approximately 300,000 members, including 30,000 based in Spain. However, limited attention has been paid to attributes influencing guests’ experiences as reviewed on nonprofit accommodation platforms such as Couchsurfing and HomeExchange.

To address that gap in the literature, this study seeks to identify and compare the attributes that influence users’ experiences with P2P accommodations by examining online travel reviews (OTRs) on three P2P accommodation platforms—Airbnb as a for-profit model and HomeExchange and Couchsurfing as nonprofit models—in the four most-visited cities in Spain. To that aim, we analyzed 765,654 reviews on Airbnb and 7,114 reviews on Couchsurfing and HomeExchange—all in English—representing the total number of reviews on those platforms from 2018 to February 2020. We interpreted and contextualized the results according to an adapted theoretical framework of the multidimensional structure of customer experience previously developed by various authors. In highlighting travelers’ preferences, the findings can help destination marketing organizations (DMOs) and the tourism and hospitality industry at large to understand the dynamics taking place on nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms, as well as help platform owners to better understand the implications of sharing platforms as business models. In turn, such insights can inform the decision-making of all parties about adopting measures to improve guests’ experiences.

2 Literature review

2.1 Nonprofit and for-profit P2P accommodation platforms

P2P platforms, as significant players in the accommodation sharing economy, have been categorized in different ways by various authors. Schor and Fitzmaurice (2015) have grouped such platforms based on their profit models as either for-profit or nonprofit; however, those categories have been criticized by Zvolska (2015) for not considering users’ contributions. By contrast, Voytenko Palgan et al. (2017) have developed another taxonomy that identifies free, reciprocal, and rental-based accommodations based on user–user interaction (see Table 1). Although free P2P platforms are the ones on which there is no monetary exchange between users, free platforms can be either for-profit or nonprofit. Meanwhile, reciprocal platforms are ones on which there is no monetary exchange between users, but a host can become a guest, and vice-versa. Last, rental platforms produce profit for both the platform and the hosts.

When it comes to guests’ experiences in accommodations found on sharing platforms, the literature is mostly based on Airbnb, which is considered to be the for-profit or rental platform with the greatest impact in the tourism industry. Airbnb’s exponential growth can be attributed to a confluence of factors that set it apart from platforms such as Couchsurfing and HomeExchange. Airbnb’s strategic incorporation of elements from the sharing economy and the hospitality industry, together with its user-friendly interface and innovative marketing strategies, have contributed to its widespread adoption. The platform’s integration of private accommodations into traditional travel experiences, enabled by a transactional model, aligns with the evolving preferences of contemporary travelers seeking unique, immersive stays. That growth trajectory is echoed by the findings of Knee (2018), who have highlighted Airbnb’s ability to leverage network effects and build a vast, diverse user base. Airbnb’s pivotal role in shaping the concept of the sharing economy and its capacity to generate supplementary income for hosts have likely fueled its exponential expansion and differentiated it from the predominantly nonprofit orientation of Couchsurfing and HomeExchange. That symbiotic relationship between Airbnb and its hosts and guests has contributed to its swift ascent to prominence and showcases a distinct model in the broader landscape of P2P accommodation platforms.

Meanwhile, although literature regarding attributes influencing guests’ experiences in the case of nonprofit accommodation platforms is limited, other topics concerning the nonprofit model have attracted increased interest among researchers (Kuhzady et al. 2020; Medina-Hernandez et al. 2020), especially in the cases of Couchsurfing and HomeExchange. On the one hand, the success of Couchsurfing lies in its exponential growth, from approximately 120,000 users in 2014 to 14 million in 2023 in more than 200,000 cities around the world. As an accommodation network, Couchsurfing presents a space held by technology where tourists can connect with hosts and stay with them without paying any fee for the whole experience. Decrop and Degroote (2014) characterized Couchsurfing as offering a form of “integrated tourism” that brings tourists and hosts closer and provides a place where users can seek out experiences, make social ties, and access “entertainment through human encounters.” On the other hand, HomeExchange is a nonprofit P2P platform with 450,000 homes offered in 187 countries in 2023. Russo and Quaglieri (2014) identified that phenomenon of home exchange offered by HomeExchange as principally a “western affair.” HomeExchange connects users interested in exchanging their homes via the digital platform in exchanges that may be reciprocal or not. The platform creates a scenario in which a host can become a guest, and vice-versa, and as it works through a points system in which users can accumulate points as they exchange their homes.

The vast majority of literature analyzing the nonprofit business model represented by accommodation sharing platforms is based on Couchsurfing. For example, Schuckert et al. (2018) conducted 14 narrative interviews with “Couchsurfers” in Austria who generally reported traveling as backpackers and, as such, seeking out diverse social interactions with locals that afford them various degrees of familiarity with destinations. They found that the act of “Couchsurfing” constitutes a cultural exchange and accommodation experience beyond mere consumption. In another example, Zgolli and Zaiem (2018) examined Couchsurfing users’ motivations in exploratory research based on a qualitative study. Their findings revealed six major motivations: financial reasons, cultural experience, the need for social interaction, professional reasons, emotional entertainment, and social responsibility. More recently, Kuhzady et al. (2020) investigated the impact of Couchsurfing as a nonprofit accommodation platform on destination image and behavioral intentions using data collected from travelers who used Couchsurfing while traveling in Turkey. Their results showed that involvement in Couchsurfing improved both destination image and revisit intention. That same year, Santos et al. (2020) performed a sentiment analysis to evaluate whether the personal contact between guests and hosts using Couchsurfing and Airbnb might influence the positivity or negativity of their reviews compared with reviews of traditional accommodations (e.g., hotels). In other work, Pera et al. (2016) quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed the personal profiles of some Couchsurfers to know whether storytelling in such profiles might predict personal reputation in the P2P community. By contrast, Decrop et al. (2018), using a qualitative approach, analyzed the motivations and shared values of Couchsurfers and found that users of the platform are motivated not only by utilitarian benefits (e.g., money) but also because they belong to a community of travelers who are also motivated by their desire for new experiences. Meanwhile, compared with the literature on Couchsurfing, the literature on HomeExchange is rather scarce, as confirmed by Casado-Diaz et al.’s (2020) review. Some studies have examined the characteristics and motivations of people who use such nonprofit P2P platforms (Andriotis and Agiomirgianakis 2014; Forno and Garibaldi 2015; Tonner et al. 2016), while other studies have investigated the impacts and spatial distribution of the home exchange practice (De Groote and Nicasi 1994; Grit and Lynch 2011; Russo and Quaglieri 2014).

2.2 Attributes that influence guests’ experiences on accommodation sharing platforms

Lemon and Verhoef (2016) have characterized the customer experience as a “customer journey,” a dynamic process starting with a pre-purchase phase (i.e., including the search for information) that shifts to the purchase and then post-purchase phases. Some researchers have analyzed guests’ experiences in accommodations found on nonprofit P2P platforms in relation to the pre-purchase phase, in which guests have external information, needs, goals, or motivations to consider while moving to the purchase phase. Other literature on user experience with Airbnb covers nearly the entire customer journey (Lin et al. 2017). As Casado-Diaz et al. (2020) have shown, however, research on accommodation sharing platforms other than Airbnb is limited, and there is a lack of information to help practitioners and scholars to understand whether there are any differences between P2P accommodation platforms with and without monetary exchange and how the business model may influence users’ experience. For those reasons, we consider it to be important to analyze whether the business model of the platform influences the experiences of users.

According to Sheth et al. (1999), the customer experience is subjective and influenced by various circumstances and factors at play in social, cultural, and personal dimensions that shape how information is absorbed. More broadly, Pine and Gilmore (1999) argued that an experience occurs when a company uses its services and products to engage its customers in creating a memorable event. Adopting that conceptualization, they have proposed the term experience economy, in which companies have to shift from selling products or services to “designing engaging experiences that command a fee.” Customer experience is fundamental to the hospitality and tourism industry (Pizam 2010), and because travelers are always seeking new, memorable experiences that enrich their trips, accommodation sharing platforms have emerged as another option to contribute to that kind of experience. With the rapid growth of the accommodation sharing industry, many scholars have examined attributes that influence users’ experiences, but most of that research has focused on for-profit accommodation platforms, especially Airbnb. Guo et al. (2019), analyzing OTRs, studied the attributes that influenced Chinese guests’ experiences and satisfaction with the P2P accommodation sharing economy platform Xiaozhu in China. They found that guests who stayed both in entire houses or apartments and in private rooms frequently mentioned “host service,” “cleanliness,” “location and transportation,” and “living environment”; however, the ones who stayed in entire houses cared more about the facilities, whereas those who stayed in private rooms favored social interaction. Meanwhile, Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) explored the major service attributes of Airbnb reported in guests’ experiences in OTRs. They discovered that the attributes that contributed most to guests’ experiences were the location, the host, and the facilities and concluded that P2P accommodations appeal to users who are driven by social and experiential motivations. By contrast, Cheng and Jin (2019), who also used text-mining techniques, investigated attributes that influenced users’ experiences using Airbnb. They revealed that Airbnb users tend to evaluate their experiences based on previous experiences with traditional hotels and identified three key attributes influencing their experiences: location, amenities, and host. They also found that price was not a key attribute of influence.

Other authors, including Lee and Tse (2020), have identified key service attributes from guests’ OTRs on Airbnb. Their findings show that negative experiences with accommodations stem from aspects related to amenities, including poor sleep quality, unpleasant check-in, or lack of hot water. A multidimensional structure of customer experience has been applied as a grounded theory approach in some studies. For example, Shi et al. (2019) identified six dimensions of Airbnb stays using qualitative analysis: spatial presence, social presence, knowledge sharing, activity sharing, host interaction, and guest interaction. In another case, Sthapit and Jiménez-Barreto (2018) used interviews to study the central elements of a memorable Airbnb hospitality experience and found that memorable Airbnb experiences related to the interaction with the host, the host’s attitude, and the location. By comparison, Li et al. (2019) investigated the multidimensional structure of the Airbnb customer experience to analyze how that experience influenced customer behavior. They identified the dimensions of home benefits, personalized services, authenticity, and social connection, all of which were found to influence users’ behavioral intentions.

More recently, in their study on value co-creation within nonprofit accommodation platforms, Medina-Hernandez et al. (2021) found that a combination of tangible and intangible resources facilitates users in co-creating value. A notable aspect is the social interaction between guests and hosts, which the platform’s model influences. For instance, with HomeExchange, social interaction relies on relationships with neighbors, locals, and small businesses, among other parties. By contrast, with Couchsurfing, the primary co-created value stems from the interaction between hosts and guests, for the platform’s operational design is intended to facilitate such encounters. With HomeExchange, however, home exchanges may limit the interaction between guests and hosts in some cases.

Table 2 provides a brief literature review of the most recent studies analyzing attributes that influence customer experience on accommodation sharing platforms. As can be inferred, most of the research has been based on Airbnb. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no academic research has been conducted on customer experience on nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms that analyzes attributes influencing guests’ experiences according to dimensions of experience. Past literature suggests that the host plays an important role in guests’ experiences; however, it is difficult to know to which extent the host is involved throughout the accommodation experience on Airbnb due to its rental characteristics. In many cases, the host simply receives the guest, brings the key, and does not return in person during the guest’s stay. Given the sharing nature of nonprofit platforms, where its users interact regularly throughout the stay, leads to experiences for guests that differ from their experiences with Airbnb as a for-profit platform.

2.3 Dimensions of experience in accommodation sharing

Regarding customer experience in accommodation sharing, several scholars have described the customer experience as a multidimensional concept that involves different components. Schmitt (1999a) and Verhoef et al. (2009) agreed on similar components, or dimensions, of the consumption experience, namely the cognitive, affective, social, and physical components. Moreover, Pine and Gilmore (1999), in their conceptualization of the experience economy, have identified four dimensions of customer experience: entertainment, education, aesthetics, and escapism. The experience has also been analyzed from other perspectives as an individual subjective construction that may be influenced by specific aspects. For example, McCarthy and Wright (2004) have studied customer experience from the perspective of technology used and Brakus et al. (2009) from a brand perspective. Although the dimensions that influence customer experience that they identified, due to contextual divergences, differ from those noted by Schmitt (1999a) and Pine and Gilmore (1999), they all agree on the existence of the emotional or affective dimension (see Table 3).

As far as the tourism experience is concerned, some researchers have used a multidimensional scale to measure such experiences. For example, Otto and Ritchie (1996) developed a four-dimensional scale (i.e., hedonics, peace of mind, involvement, and recognition) of the tourism experience. Their scale was confirmed and enlarged by Kim et al. (2012), who consequently proposed a seven-dimensional scale (i.e., hedonism, novelty, local culture, refreshment, meaningfulness, involvement, and knowledge) in the construction of a memorable tourism experience. Other authors have adapted Pine and Gilmore’s (1999) approach in specific contexts, including tourists’ experiences with temple stays (Song et al. 2015). Indeed, research in that field has been rather extensive, as shown in Table 3. Regarding tourist experience in relation to accommodation sharing following a multidimensional theory approach, all research conducted so far has been based on Airbnb. In such work, Mody et al. (2017) adapted Pine and Gilmore’s (1999) approach in their comparison of customer experience in hotels versus Airbnbs and added the dimension of hospitableness to the four-dimensional scale. Moreover, Shi et al. (2019), arguing that the experiential aspects of accommodation sharing have received limited attention in research, adopted two dimensions (i.e., authentic and cultural experience)—both based on a review of tourism experience—in their study on home-based accommodation sharing experiences with Airbnb as a reference.

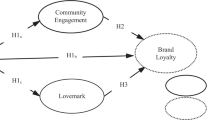

Based on the foregoing literature review, in our study we adopted three major dimensions: affective, cognitive, and authenticity. The cognitive dimension was conceived as the previous knowledge or expectations that an individual has about the environment (Oliver 1993), as well as the physical and spatial characteristics of the resource or place (Marine-Roig 2019). The affective dimension was conceived to involve feelings and emotions while in that environment (Schmitt 1999b; Baloglu and McCleary 1999; Marine-Roig and Ferrer-Rosell 2018). Last, the dimension of authenticity was conceived as an existential perception (Wang 1999). According to Wang (1999), existential authenticity arises from the balance between reason and emotion and can thus be seen as resulting from both the cognitive and affective dimensions. In the context of P2P accommodations, that concept places particular emphasis on the nature of the accommodation sharing experience (Yannopoulou 2013) and how it aligns with local values and creates memorable experiences (Adams 1984; Shi et al. 2019) and thereby becomes meaningful for the tourist and related to their sense of self. Existential authenticity may have nothing to do with the authenticity of tourism objects (Wang 1999) and instead refers to a state of being reached through the performance of certain meaningful activities. What matters is the significance of the lived experience, which is activity-based, not object-based (Rickly-Boyd 2013). As Rickly-Boyd (2013) has explained, “existential authenticity is not created in isolation within the individual, but occurs in fleeting moments, informed by social, cultural, and physical encounters” in a certain place through action and interaction. Although experience is the center of the tourism industry, to our knowledge only little research has been conducted on analyzing which attributes influence guests’ experiences in P2P accommodations beyond Airbnb, and even less research has been conducted using dimensions of the perception of experiences to interpret and categorize those attributes.

3 Research method

In this study we employed a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Our methodological process followed the general steps of data collection, cleaning, pre-processing, and, finally, quantitative content analysis, in which an inductive reasoning approach was used to identify the attributes and, in turn, qualitative reasoning based on text classification to link those attributes to dimensions of experience (see Fig. 1). Attributes emerged after reviewing the OTRs by way of quantitative content analysis or text mining. In particular, we analyzed OTRs of users on a for-profit P2P accommodation platform (i.e., Airbnb) and two nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms (i.e., Couchsurfing.com and HomeExchange.com). Concerning the data collection stage, Airbnb reviews were obtained from the website InsideAirbnb (www.insideairbnb.com), while reviews on the nonprofit platforms were extracted from each platform using the web scraper software WebHarby, version 6.0.1.173, previously used by other authors to access data (Khotimah and Sarno 2018; Laksono et al. 2019).

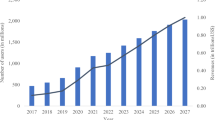

Airbnb is considered in this study due to its importance in the P2P accommodation platform sector as the most representative for-profit business model, with 5.6 million active listings worldwide as of September 2020 (www.Airbnb.com 2020), while we selected HomeExchange and Couchsurfing given their exponential growth as nonprofit accommodation platforms (Casado-Diaz et al. 2020; Kuhzady et al. 2020). Spain as a tourist destination, we chose Spain due to its importance as a worldwide tourist destination—in 2019, it ranked among the top 10 destinations in terms of international tourist arrivals (World Travel Organization 2019)—and given the proliferation of shared accommodations in the country in recent years (Palos-Sanchez and Correia 2018). Although other researchers have studied the phenomenon of Airbnb in Spain (Adamiak et al. 2019; Huertas et al. 2021; Gutiérrez et al. 2017), most of their research involved analyzing patterns in the distribution of Airbnbs and their impact on the housing market, gentrification, and pricing issues. As a consequence, there is a lack of information regarding user experience in that context and even less information about the possible dynamics created by users of nonmonetary P2P accommodation platforms. We thus collected data from listings on those three platforms in the four most-visited cities in Spain: Barcelona, Madrid, Seville, and Valencia (Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España 2020). Only guests’ reviews in English were considered, being that English was the most common language in the reviews. OTRs from 2018 through the end of the data collection period (i.e., February 2020) were extracted. Those years were selected due to the considerable increase of users in the nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms that we examined. Data cleaning involved automatically selecting reviews in English and eliminating reviews in other languages and OTRs with symbols only or without content. That data-refining process resulted in a total of 765,654 guest reviews from the for-profit accommodation platform Airbnb and 7,114 guests reviews from the nonprofit accommodation platforms Couchsurfing.com (n = 6,208) and HomeExchange.com (n = 934).

Next, the data were pre-processed so that data-mining techniques could be applied to quantitatively analyze the text in the reviews. In that stage, a list of stop words (i.e., a list that includes common words occurring in all kinds of sentences, including adverbs, prepositions, and words with no meaning) was elaborated and introduced to the software. Those stop words were not included in the analysis. American and British spellings of words were also unified in that step. Then, the final step, content analysis, involves three substeps.

-

A.

First, a keyword frequency analysis and sentiment analysis were conducted. The keyword frequency analysis involved counting of how many times a term appeared in the text and the density of use, in percentages, throughout the entire data set. In the process, we also investigated sentiments conveyed in the reviews. For sentiment analysis, the list of the most frequent words and the percentages of their appearance in the reviews were considered. Using that initial list, a new list of words related to positive feelings, including “good,” “useful,” and “excellent,” and another list of words related to negative feelings, including “bad,” “boring,” and “uncomfortable,” were created. Some positive and negative terms from a dictionary were added to complete both lists. From those two lists, the total of keywords related to positive or negative feelings, as well as the percentage that the total represented on each platform, was obtained. That percentage represented the number of occurrences of keywords indicating feelings in relation to the total words, including stop words.

-

B.

Second, the co-occurrence networks of keywords for each platform were obtained. Co-occurrence networks of keywords are diagrams that capture words with similar patterns of appearance—in other words, with high degrees of matching. Each diagram shows words (i.e., nodes) with similar patterns of appearance and with high degrees of co-occurrence connected by lines (i.e., edges). Although one node may be situated close to another, if they are not connected by edges, then strong co-occurrence does not exist. Thicker edges indicate a stronger co-occurrence, and larger nodes represent higher-frequency words. Words in the same group of words (i.e., subgraph) are connected by solid edges, while those in different groups of words (subgraphs) are connected with dashed edges. Subgraphs are used to represent parts of the network that are more closely associated with each other through color-coding. In the color-coding scheme of KH Coder software, a word on a white background enclosed in a black circle is independent (Higuchi 2016). Subgraphs help to detect the most common patterns in the appearance of words. The co-occurrence network has been used as an analytical technique from the very beginning of content analysis (Osgood 1959). Since then, Tussyadiah and Zach (2015), for instance, have used the co-occurrence network to explore the competitive edge of P2P accommodations compared with hotels by extracting key themes from OTRs to explain the key service attributes of guests’ experiences.

-

C.

From the co-occurrence network, the attributes that influenced users’ experience were deducted. To do that, we selected the most frequent term or node word in each subgraph (i.e., group of words) from the co-occurrence network. Then, focusing on that node word, collocation statistics with other words were calculated. Those listed words had a direct association with the original node word. The list of words received a score representing the frequency and intensity of relationship with the node word (see Tables 5, 6 and 7). Each default score using the function f(w) was computed by the software using the following equation:

As the equation shows, “In general, the greater the frequency that a certain word w appears before or after the node word (li+ ri), the larger the value f(w)” (Higuchi 2016; pp. 39–40). To calculate f(w), frequencies (li+ ri) are divided by i, “which weighs the frequencies according to their distance from the node word. Thus, words that appear nearer to the node word (i.e., with a smaller i) have greater weight than those that occur before or after the node word” (Higuchi 2016; pp. 39–40).

Next, the group of words was given a name (i.e., attribute), and each word in that list, using collocation statistics, with its score represents the elements related to each attribute. The same procedure was conducted with each co-occurrence network identified for each P2P accommodation platform.

It is worth noting that this research proposes an in-depth and progressive analysis from small, unique units of analysis, which are the terms (keywords) to the identification and definition of attributes that influence the experiences of P2P accommodation users based on how the terms co-occur and relate to one another. Using qualitative analysis, once the characteristics and the elements or group of words related to each attribute were identified, each attribute that influenced guests’ experience was linked with an accommodation sharing experience. Doing so helped to determine which attributes were more closely related to the cognitive, affective, and authenticity dimensions. Using KH Coder software, we identified and read the reviews in which each of the terms related to each attribute appeared in order to classify each term into one of the dimensions. That qualitative process allowed the researchers to consider the context, tone, and sentiments expressed in the review to perform a better classification of the text. For instance, if a term within the attribute was “beautiful,” which appears in the destination attribute of Couchsurfing, we referred to the specific reviews in which that word appeared using the software KH Coder. To that end, two authors classified each review into a dimension, and any discrepancies were resolved by the third author. The reading of those reviews ceased when no new information could be collected. Those steps of content analysis were performed with the support of KH Coder 3 software, which is a free software for quantitative content analysis or text mining that performs well in analyzing English-language data and is also utilized for computational linguistics (Baltranaite and Povilanskas 2019; Hemsley et al. 2018). The statistical analysis function Standford POS tagger was used, which classifies data considering not only the word but also its conjugation, thereby helping to construct a more accurate group of words.

4 Results

This section presents the results of our analyses, beginning with the keyword frequency and sentiment analyses, followed by the analysis of the co-occurrence networks of words. Once the attributes influencing guests’ experiences were obtained, they were defined and characterized according to the cognitive, affective, and authenticity dimensions of the perception of guest experiences.

4.1 Keyword frequency

Table 4 shows the top 25 keywords from the OTR analysis of each platform, the number of occurrences of every keyword, and the percentage that each keyword represents out of the total number of words, including stop words. From a general perspective, the top 25 keywords point to different elements that contribute to guests’ experiences depending on how the platform operates.

First, Couchsurfing’s top 25 keywords included words such as “friend” and “friendly,” which are positive terms typically used to describe hosts. Their inclusion stresses the importance for guests of having a host who establishes an emotional connection during their stay. Other words, including “guy,” “host,” and “time,” strengthen the idea that, on Couchsurfing, the characteristics of the room, “bed,” or “couch” are not as important as an active relationship with the host.

Second, as shown in Table 4, some of the top keywords derived from HomeExchange.com were “apartment,” “home,” “place,” and “exchange,” which seem to be the main factors of guests’ experiences on the accommodation platform, in contrast to Couchsurfing’s keywords. “Family” is another word that is commonly used by guests in their reviews, not only because guests tend to travel with family but also because sometimes the host’s entire family is involved. Here is an example of a sentence written by users in that respect:

We stayed 4 nights in this lovely house. As soon as we met Lupe and her family members, Luis, Pablo, and Juliet, they really welcomed us.

Third, for the for-profit platform, we found that Airbnb’s top keywords related to the characteristics of the accommodation. “Apartment,” “room,” and “place” were some of the most common keywords in the reviews on Airbnb. Moreover, guests using the platform used words such as “clean,” “location,” “comfortable,” “restaurant,” and “locate.” Those kinds of words are akin to ones used in describing a traditional accommodation (e.g., hotel), and it can be deduced that guests expect to find attributes similar to those in traditional accommodations (hotels).

As shown in Table 4, a considerable number of key terms related to feelings. In that case, good feelings were mentioned more than bad feelings, which may denote a generally positive P2P accommodation experience. That amount of positive feelings is also important because such words convey lived experience, or experience related to personal feelings “activated by the process of tourist activities” (Marine-Roig and Anton Clave 2016). However, in general, Airbnb had the highest percentage of negative feelings, probably related to the fact that because users pay, they expect certain services in return. That scenario reaffirms what some scholars have called “destination image,” which considers the accommodation to be an element in the construction of the destination that is not only the expression of ideas, expectations, or the imagination but also of emotional thoughts and feelings about a place (Bandyopadhyay and Morais 2005).

4.2 Co-occurrence networks of words

After the high-frequency keywords were identified, a co-occurrence network analysis of words was conducted. Figure 2 shows the patterns of words’ appearance and the co-occurrence between words used in guests’ reviews on Couchsurfing. Subgraphs 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 10 are of particular interest. It can be deduced from the figure that for Couchsurfing guests, accommodation is considered to be an experience in itself (subgraph 6, orange) more than simply a place to stay. Also, person-to-person interaction plays a significant role in guests’ experiences, as represented by words in subgraphs 1 (light blue), 4 (red), and 5 (dark blue): “meet” and “person,” “friend,” “nice” and “guy,” “tell” and “story,” and “accept” and “request.” Those last words relate to the host and the time that the host spends in accepting a guest’s request. As shown in subgraph 9 (pink), two words with a strong co-occurrence are “conversation” and “interesting,” which indicates the importance for guests of the interaction with hosts.

By contrast, HomeExchange’s co-occurrence network, shown in Fig. 3, indicates a higher co-occurrence between the words “great,” “apartment,” “exchange,” and “stay.” This word exchange is used in the reviews of this platform, given the way it works, with mutual home exchanges. Words related to the location of the accommodation and good access to places of interest also have strong co-occurrences, as shown in subgraphs 3 (purple), 4 (red), and 6 (or orange).

Subgraph 9 (gray) shows the co-occurrence between the words “highly” and “recommend” and the co-occurrence with the word “exchange,” although its co-occurrence is weak. The characteristics of the accommodation (i.e., “clean,” “comfortable,” and “location”), places of interest (i.e., “restaurant,” “bar,” and “city center”), and means of transportation (i.e., “bus” and “metro station”) are also elements highlighted in guests’ reviews on the platform.

Another element worth highlighting is the co-occurrence of the words “home” and “family” and “make,” “feel,” and “home,” as shown in subgraph 2 (yellow), which indicates a tendency of guests to positively value the accommodation if it offers the same or similar benefits as their own home and if it can accommodate not only one guest but entire families. That trend is understandable considering that HomeExchange is a home exchange platform.

Last, results from Airbnb (Fig. 4) revealed a highly strong tendency of guests to consider elements related to the accommodation itself. Strong co-occurrence was found between words such as “great,” “apartment,” “host,” “clean,” “location,” “stay,” and “place.” Those words (i.e., nodes) had a higher appearance frequency, as shown in subgraph 6 (orange). There was also strong co-occurrence between the words “metro” and “station” and between “city” and “center” regarding places of interest. It can be deduced that guests positively valued some accommodation facilities, as demonstrated by the co-occurrence of “comfortable” and “bed” in subgraph 11 (green) and “room,” “bathroom,” and “kitchen” in subgraph 2 (yellow). The results, however, did not reveal any evidence of interaction between guests and hosts or a large pattern of the appearance of words related to experiences. Most of the subgraphs show words related to elements that could also be considered by guests in nonprofit P2P accommodations.

4.3 Attributes influencing guests’ experiences

Based on the results of the co-occurrence networks, the attributes and elements referring to each attribute influencing guests’ experiences on the nonprofit and for-profit accommodation platforms were deduced as explained in the methodology. Tables 5, 6 and 7 show the attributes that influenced guests’ experiences and the elements inherent to each attribute for each P2P accommodation platform.

4.3.1 Attributes derived for Couchsurfing

For Couchsurfing, four main attributes influencing guests’ experiences were identified, as shown in Table 5.

-

a.

Destination

The attribute of destination included, among other words, “center/centre,” “explore,” “walk,” “enjoy,” and “Barcelona” (see the score for each word in Table 5) and seems to have played an important role in guests’ experiences. Accommodations on Couchsurfing, as one of the most relevant P2P accommodation platforms, are readily available for guests in urban tourism destinations. Considering the scope of our study and the four cities analyzed, “Barcelona” was the word with the strongest pattern of appearance within the attribute of destination. Also, within that attribute, the word with a relatively high score was “center/centre,” meaning that it was a word with a high frequency and intensity of relationships with the attribute. In that attribute, most terms or elements may relate to the cognitive dimension because they relate to a spatial aspect.

b. Interaction

The second attribute identified in the reviews analyzed was interaction. Within that attribute, the element with the strongest relationship with the attribute was “cook dinner.” The attribute included words such as “Spanish music,” “share,” “talk,” and “eat,” possibly owing to how the platform operates and how it requires the presence of the host during the guest’s stay, which helps interaction to occur. Stays using the platform also tend to be short—on average, only three days. Guest conceive Couchsurfing as an experience (Kuhzady et al. 2020), and the interaction that guests have with their hosts during their brief stays helps to enrich their experience. That attribute and most of its elements may relate not only to the dimension of authenticity, given their connection with local activities and things to do, but also to a particular travel philosophy that Wang (1999) called “existential authenticity.”

c. Host

The third attribute was “host,” which included words, primarily adjectives, such as “nice,” “interesting,” “funny,” “helpful,” and “kind.” The attribute influences the experience of guests due to the implicit relation and interaction between guests and hosts. Because both parties have to interact, a host who offers good conversation and an interesting or funny point of view improves the guest’s experience. Therefore, the host is a key element in Couchsurfing. Representing that attribute, most of the elements were adjectives that indicate emotional thoughts, and the majority of words expressed positivity. Therefore, that attribute was primarily related to the affective dimension.

d. Facilities

The fourth attribute identified was “facilities,” which included words such as “clean,” “beautiful,” “cozy,” and “comfortable.” Unlike with Airbnb, where guests put the most value on accommodation facilities, facilities are not as important as the other attributes for users of Couchsurfing; even so, they influence the experience of guests. Guests mostly seek clean accommodations; however, as mentioned, the stays tend to be short, and the accommodation itself does not play a starring role in the experience. The attribute of facilities mostly related to the affective component because most of its elements evaluated personal experience, with terms such as “good,” “comfortable,” and “nice.” (See Fig. 5).

4.3.2 Attributes derived for HomeExchange

Table 6 shows attributes and elements related to them that influence guests’ experiences on HomeExchange.

-

a.

Destination

As with Couchsurfing, destination was the first attribute identified. In their experiences, guests positively valued places at the destination. The word “neighborhood,” for instance, indicates that hosts value their experience more when the accommodation is in a safe, well-located neighborhood and has various amenities. Examples of HomeExchange users’ reviews on that count include:

-

“Neighborhood is just fantastic (many restaurants, shops, groceries,…!).”

-

“It’s close to everything—transit, shops, restaurants, and the beach!”

-

“Their apartment is very nice, quiet, and sunny. They are well located: metro station is across the street, many bus stops in Gracia.”

Because stays using the platform tend to be long, guests want the accommodation to be in a safe neighborhood with stores and that is convenient to places of interest. The attribute mostly related to the dimension of authenticity, for it represents the possibility for guests to experience life as locals do within a local environment.

-

b.

Interaction.

The attribute of interaction included the words “home,” “great,” “recommend,” “wonderful,” “perfect,” “experience,” and “simultaneous.” The exchange develops with fluid communication between guests who seek homes that fulfil their expectations and becomes an experience in itself. Guests value the accommodation even more when the process goes well—for example:

Actually, we had our very first exchange with Laura and we were more than happy to start our Home Exchange experience with her.

The attribute had an affective vein because most of its elements related to emotional adjectives or evaluations.

-

c.

Host

As on Couchsurfing, the host emerged as an attribute that plays an important role in guests’ experiences, one represented by words such as “great,” “perfect,” “wonderful,” “excellent,” “helpful,” and “family.” The word “family” is an element of the attribute because home exchanges usually occur between families, such that the welcoming family becomes the host. The host influences the guest’s experience by being present not only during the accommodation experience but also before the exchange. The communication between hosts and guests before, during, and after exchanges is also an element within that attribute due to the importance for guests of a long-term relationship with their hosts. The attribute was mostly related to the affective dimension, for it represents positive feelings that emerged from the guests’ experience with the host.

-

d.

Facilities

On HomeExchange, the attribute of facilities included words such as “kitchen,” “car,” “decorate,” and “toy.” Guests valued their experience more when they had the opportunity not only to stay in the house but also to use other elements, including the host’s car or the toys of the host’s children, as captured in the following reviews:

-

“They even left us their car for a few days after their return to give us the opportunity to meet with our friends in France.”

-

“Our son is about the same age as their children so we enjoyed all the toys and car booster they lent us.”

Last, in the attribute of facilities, most elements were connected to the dimension of authenticity due to elements at the accommodation that enable guests to have a local living environment (Shi et al. 2019). At the same time, the affective dimension also seems to play a relevant role given elements such as “comfortable.” In this attribute, the dimension of authenticity related to existential experience, which involves intersubjective feelings that emerge from tourists’ activities (See Fig. 6).

4.3.3 Attributes derived for Airbnb

In the case of Airbnb, three major attributes were identified (Table 7): host, destination, and facilities.

-

a.

Host

Even if the analyzed reviews present no generalized evidence of interaction between guests and hosts, in their reviews guests considered hosts as an influential element of their accommodation experience, described using adjectives such as “great,” “friendly,” and “helpful.” All elements in that attribute related to the affective dimension.

-

b.

Destination

In their reviews, guests used terms related to places of interest. In the top 10 were elements such as “tourists,” “city,” “restaurant,” and “metro.” In general, guests in Airbnbs spend most of their time outside the accommodation, for they value spending time in local neighborhoods (Tussyadiah and Zach 2016). For that reason, the perception of the experience and the destination image are constructed primarily outside the accommodation. In that case, the attribute had a cognitive dimension in being related to the guests’ expectations about the spatial element.

-

c.

Facilities

A final attribute influencing Airbnb guests’ experience was facilities. Guests value finding a clean accommodation as an influential attribute of their accommodation experience. They used terms such as “super clean” and “sparkling” in relation to the attribute. The attribute of facilities was mostly related to the affective dimension (See Fig. 7).

Although some studies on attributes of experience derived for Airbnb have identified price or cost savings as a determining attribute of guests’ experiences, others have pointed out that, in some cases, price is not a relevant element of experience (Cheng and Jin 2019). Those contradictory findings, as Tussyadiah (2016) has indicated, may occur due to the lack of standardization of Airbnb accommodations.

On the nonmonetary platforms, the attributes that influenced users’ experiences, as shown in Table 8, also have different implications. Due to the exchange-based nature of HomeExchange and the long periods of home exchange, the interaction between users requires constant communication, and users often wrote the words “partner” and “experience.” The host and guest often develop a close relationship that can last beyond the hosting experience. By some contrast, on Couchsurfing, whose users’ stays tend to be shorter, guests find interactions with their hosts to be more valuable as an attribute of their experience. The activities that they can engage in together in a local, authentic environment reinforce that interaction.

5 Discussion

Comparing the results of our study with the findings of previous research can provide valuable insights into the attributes and dimensions that shape user experiences on P2P accommodation platforms. Whereas prior studies have predominantly focused on cognitive and affective dimensions, we extended that analysis by incorporating the dimension of authenticity. For instance, Pera et al. (2016) have underscored the importance of self-storytelling in building personal reputation within collaborative communities. That finding aligns with our identification of attributes in the cognitive dimension that relate to guests’ expectations and prior knowledge, which illustrates how those narratives contribute to perceptions of users’ experiences.

Our results also extend previous interpretations of the attributes that shape user experiences by organizing the attributes according to for-profit and nonprofit platforms in three dimensions that form the lodging experience: the cognitive, the affective, and the authenticity dimension. Our study revealed that, on nonprofit platforms, the attributes were indeed linked with the three dimensions; however, in the case of Airbnb, the OTRs analyzed were primarily linked with the affective and cognitive dimensions. Those results can be compared with the findings of previous studies. For example, Sthapit and Jiménez-Barreto (2018) concluded that the attributes influencing guests’ experiences on Airbnb were price, location, and host, thereby linking a social dimension with the host. However, and as our results confirm, price was not an influential attribute of guests’ experiences, and the attribute of the host mostly related to the affective dimension due to the lack of deep guest–host interaction.

Our findings additionally confirm the findings of Tussyadiah and Zach (2017) regarding the importance of the attributes of facilities and the destination for guests’ experiences. When users stay in an Airbnb, they expect to have similar amenities to the ones received during past hotel stays (Cheng and Jin 2019). For that reason, the facilities and location of the destination have remained important. However, their results also highlight attributes such as “feeling welcome” that instead relate to some sort of social dimension. Even so, the wording of “feeling welcome” also reveals that, in Airbnbs, the host is relevant only at specific moments—sometimes only when welcoming guests—and does not engage in activities with guests. The result is a lack of any profound interaction.

In other work, Schuckert et al. (2018) have highlighted the significance of Couchsurfing as an experience of cultural exchange that fosters authentic interactions. Our identification of attributes associated with the dimension of authenticity on nonprofit platforms supports that notion, especially by highlighting the role of host–guest interaction in creating an authentic experience. Moreover, in light of Gerwe’s (2021) discussion of the disruptions faced by the accommodation sharing sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, our findings emphasize how the authenticity accentuated on nonprofit platforms may contribute to their resilience in times of crisis.

Our findings also align with the results of Özgen and Biçakcioğlu-Peynirci’s (2020) investigation of the experiential dimensions of the collaborative consumption journey in terms of sensory, affective, and cognitive experiences reported on both Airbnb and Couchsurfing. Along those lines, our findings indicate that attributes related to those dimensions play a pivotal role in reviews on both nonprofit and for-profit platforms.

Santos et al. (2020) have offered insights into determinants of guest satisfaction and the significance of communication, the space, and information about the surroundings. Those findings resonate with our study’s identification of attributes related to cognitive and physical dimensions in guests’ experiences on both types of platforms. Santos et al. (2020) found that reviews within the sharing economy on Airbnb and Couchsurfing tend to be more positive than reviews of traditional accommodations. That result also aligns with our findings in the sense that the host’s presence might influence the guest’s experience and possibly their recollection of the experience during the recommendation phase.

In another vein, Decrop et al. (2018) have identified that the adoption of Couchsurfing hinges on socialization and acculturation. Their study revealed interactions not only between guests and hosts but also between guests and the local community, a notion that our findings strengthen in showing that genuine experiences require interaction not merely between guests and hosts but also with the environment.

Last, our investigation dovetailed with prior research endeavors, including Pino et al.ʼs (2022) study, which aimed to enrich the ever-evolving landscape of P2P services. By exploring the nexus between customers’ identification with service providers, psychological ownership of service settings, and customer–provider interactions, their work underscored the interplay that drives attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. That dynamic emerged particularly through cooperative interactions with service providers, which aligns with our findings underscoring the pivotal role of host–guest interactions in nurturing authentic experiences on nonprofit platforms. Such convergent evidence further confirms the value of genuine engagement in fostering customer loyalty and positive service outcomes.

In sum, comparing our results with the findings of previous research highlights the multifaceted dimensions that influence guests’ experiences on P2P accommodation platforms and how those dimensions interact to create distinct perceptions among guests. Such a synthesis enriches current understandings of the experiential attributes that define the for-profit and nonprofit segments of the sharing economy.

6 Conclusions and implications

This study has contributed to closing the gap in the literature regarding attributes that influence perceptions of guests’ experiences in accommodations found on nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms. It has provided not only a comprehensive analysis of those attributes in both for-profit and nonprofit accommodation platforms but also a model to interpret them in relation to dimensions of experience. Although other studies have analyzed attributes that influence users’ experiences on P2P accommodation platforms, we contribute by offering the first study to have used the twofold method of quantitative text analysis, namely to identify the attributes, and qualitative analysis, to classify them into dimensions and compare the results between nonprofit and for-profit P2P accommodation platforms.

6.1 Contributions to theory and methodology

Although previous research on peer-to-peer accommodations has considered the dimensions of experience, it has mostly focused on the dimension of authenticity without considering physical elements (i.e., cognitive dimension) or emotional aspects (i.e., affective dimension) that may also influence the perception of users’ experiences. In response, we have proposed a new three-dimensional model of the perception of experiences to interpret the attributes that may influence guests’ experiences with accommodations. We have also extended the interpretation of attributes of experience by connecting the identified attributes in for-profit and nonprofit platforms with three dimensions that form the lodging experience: the cognitive, the affective, and the authenticity dimensions.

Our results show that, on nonprofit platforms, the attributes were linked with the three dimensions (i.e., cognitive, affective, and authenticity); however, in the case of Airbnb, the OTRs analyzed were mostly linked with the affective and cognitive ones. In that regard, our results show that the chief difference in guests’ perceptions of nonprofit and for-profit P2P accommodation experiences is authenticity, which was emphasized only on nonprofit platforms linked to host–guest interaction. From the reviews analyzed, it can be concluded that the attribute of interaction, conceived as the interaction between guests and hosts, had more influence on guests’ experiences on nonprofit P2P accommodation platforms than on the for-profit one. Although hosts of the latter type of accommodations influence the guest’s experience, it is at a surface level, whereas such interaction on nonprofit platforms was the chief trigger of the perception of authentic experience.

The methodological contribution of our work is twofold. First, our results emerged from a massive amount of OTR data, which were subjected to a progressive, extensive quantitative content analysis. In that analysis, we began with the smallest unit (i.e., words), established the relationship between words and their importance (i.e., in a co-occurrence network), deduced the major attributes from the main nodes of the network, and qualitatively analyzed the content associated with each node according to the cognitive, affective, and authenticity dimensions. Second, to the best of our knowledge, no other research has identified those dominant attributes and applied textual analysis using that type of process on nonprofit P2P platforms and comparing them with a for-profit platform.

6.2 Managerial implications

This study can be used by policymakers and DMOs to design and implement strategies based on the real practices of tourists, primarily guests on nonprofit accommodation platforms, that improve their experiences at destinations and may enhance existential authenticity. They also can assist accommodation sharing platforms and hosts in providing guests with high-quality experiences. One approach to that end involves promoting cultural collaboration, in which both hosts and guests receive complimentary tickets to city cultural events that they attend together. The initiative fosters interaction between hosts and guests while enriching the cultural aspects of the destination. Moreover, DMOs can organize workshops offering local experiences that teach guests and hosts unique local skills or crafts, which would support local artisans and adding authenticity to the experience. Community tours led by locals can reveal hidden gems and offer a more genuine understanding of the destination, all while encouraging hosts and guests to participate together. Beyond that, culinary experiences, including cooking classes and food tastings in partnership with local restaurants or chefs, can allow guests to immerse themselves in local cuisine and bond with hosts over shared meals. Environmental initiatives, including community clean-up events and tree-planting activities, also enable guests and hosts to contribute to the destination by embracing eco-friendly practices. Language exchange programs additionally facilitate cultural exchange as guests and hosts teach each other their native languages. For their part, DMOs can also provide information about local festivals and events to encourage hosts to accompany guests to those occasions for a deeper understanding of local traditions. For instance, arts and crafts workshops in collaboration with local artists and craftspeople offer a hands-on souvenir creation experience that adds value to the trip. DMOs can also connect guests and hosts with local volunteer organizations, thereby providing opportunities to guests to give back to the community that they are visiting, which can afford a more meaningful experience. From another angle, host training sessions can empower hosts to provide exceptional experiences that improve the quality of accommodations and interactions. Of course, because attributes of Airbnbs are relatively similar to attributes of experiences at hotels, Airbnb hosts can improve their services by offering exceptional and high-quality amenities in their accommodations that improve guests’ experiences. On top of that, Airbnb can design strategies to generate more interaction between guests and hosts, given the influence of the attribute of interaction in experiences accessed on nonprofit accommodation platforms and, in that sense, avoid becoming just a low-cost rental accommodation platform.

Guests using nonprofit platforms seek memorable, authentic experiences influenced mostly by interactions with their hosts. For that reason, destinations should keep in mind that affording guests an enjoyable lodging experience by using those kinds of platforms aids the development of positive destination image for potential visitors (Baloglu and McCleary 1999), for those guests may act as subscribers of the destination. Such memorable, authentic experiences also relate to their existential values (e.g., self-identity, culture, perceived ideas, and personal growth) (Wang 1999; Rickly-Boyd 2013). The latter reason also explains why guests of those kinds of platforms may be more attractive for a destination given their travel philosophy and how they connect through interacting with hosts in the local environment. Although the volume of tourists in a city using nonprofit P2P accommodations is less than the volume of ones staying in hotels or Airbnbs, their experiences are more authentic and, therefore, more satisfactory.

Our findings highlight the importance of P2P services for the up-and-coming generation of tourists. With the new era of users who increasingly subscribe to the sharing economy and sustainable consumption, in which experience is a service in itself, designing authentic services adapted to them will help P2P platform owners to understand guests’ preferences and, based on that, create products and services that meet their needs.

6.3 Limitations and future research

The major limitation of this study was its exclusive focus on the Spanish context. For that reason, our results might be different in other contexts. Moreover, although we analyzed more than 700,000 OTRs on P2P accommodation platforms, they were all written in English between 2018 and February 2020, and the number of OTRs from Airbnb was significantly higher than the number of OTRs analyzed for the other two platforms. We also analyzed data from before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the perception of experience attributes might have changed since then. Last, regarding the research technique used, the categorization of attributes might have involved some subjectivity.

In view of those limitations, future research could compare OTRs from previous and post-pandemic contexts. Languages other than English could also be considered to observe cultural or behavioral differences. For instance, are users writing in Spanish or French influenced by the same attributes as those writing in English on both types of P2P accommodation platforms? Moreover, it could be helpful to consider the country of residence of guests, for there may be some cultural implications of nationality. Our study should also be extrapolated to the world’s other top 10 tourist destinations to discover whether results differ from one destination to another. Future research could additionally be carried out using other software for textual analysis—for example, Iramuteq—and other multivariate statistical techniques, including cluster or correspondence analysis, to segment and profile users.

Future research could also illuminate our results by discriminating reviews on Airbnb between users who have rented a single room and ones who have rented an entire accommodation. Moreover, future studies could focus on the nuanced dynamics of the perception of user experience across a broader spectrum of P2P accommodation platforms. Investigating how those three dimensions—the cognitive, affective, and authenticity dimensions—interact and evolve over time could provide valuable insights into the evolving nature of guests’ experiences. On that count, exploring the extent to which those experiential attributes are influenced by cultural, geographical, and demographic factors could also offer a more comprehensive understanding of their impact. From another direction, conducting longitudinal studies that track changes in users’ reviews and perceptions could shed light on the long-term effects of host–guest interactions on authenticity and emotional resonance on both nonprofit and for-profit platforms. Furthermore, examining the role of platform design and features in shaping those dimensions and their effects on user experiences could open avenues for enhancing the platforms’ effectiveness and users’ satisfaction. On top of that, considering the evolving landscape of the sharing economy (i.e., investigating how emerging platform models and innovative sharing concepts align with or reshape those dimensions) would contribute to a holistic comprehension of the P2P accommodation phenomenon. Last, future research on nonmonetary collaborative accommodation platforms, considering the results of our study, needs to investigate whether the dimension of authenticity remains the most significant. To further explore those dynamics, it would be pertinent to extend the analysis to additional platforms with similar nonmonetary models and include more recent reviews, particularly to learn whether authenticity remains predominant or if other emerging dimensions have come into play.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the fact that they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adamiak C, Szyda B, Dubownik A, García-Álvarez D (2019) Airbnb offer in Spain-Spatial analysis of the pattern and determinants of its distribution. ISPRS Int J Geo-Information 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8030155

Adams JS (1984) The meaning of housing in America. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 74:515–526

Airbnb (2020) About us. https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/

Andriotis K, Agiomirgianakis G (2014) Market escape through exchange: home swap as a form of non-commercial hospitality. Curr Issues Tour 17:576–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.837868

Baloglu S, McCleary KW (1999) U.S. international pleasure travelers’ images of four Mediterranean destinations: a comparison of visitors and nonvisitors. J Travel Res 38:144–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759903800207

Baltranaite E, Povilanskas R (2019) Quantitative content analysis of the influence of natural factors on the competitiveness of South Baltic seaside resorts using the KH coder 2.0 method. In: Geophysical Research Abstracts

Bandyopadhyay R, Morais D (2005) Representative dissonance: India’s self and western image. Ann Tour Res 32:1006–1021

Bao Y, Ma E, La L et al (2022) Examining the Airbnb accommodation experience in Hangzhou through the lens of the Experience Economy Model. J Vacat Mark 28:95–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/13567667211024707

Belarmino A, Whalen E, Koh Y, Bowen JT (2019) Comparing guests’ key attributes of peer-to-peer accommodations and hotels: mixed-methods approach. Curr Issues Tour 22:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1293623

Bigne E, Fuentes-Medina ML, Morini-Marrero S (2020) Memorable tourist experiences versus ordinary tourist experiences analysed through user-generated content. J Hosp Tour Manag 45:309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.019

Botsman R, Rogers R (2010) What’s mine is yours: how collaborative consumption is changing the way we live. Collins Business, New York, NY

Brakus JJ, Schmitt BH, Zarantonello L (2009) Brand experience: what is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? J Mark 73:52–68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.3.052

Brochado A, Troilo M, Shah A (2017) Airbnb customer experience: evidence of convergence across three countries. Ann Tour Res 63:210–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.01.001

Casado-Diaz MA, Casado-Díaz AB, Hoogendoorn G (2020) The home exchange phenomenon in the sharing economy: a research agenda. Scand J Hosp Tour 0:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2019.1708455

Cheng M, Jin X (2019) What do Airbnb users care about? An analysis of online review comments. Int J Hosp Manag 76:58–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.04.004

Cheng X, Fu S, Sun J et al (2019) An investigation on online reviews in sharing economy driven hospitality platforms: a viewpoint of trust. Tour Manag 71:366–377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.020

Couchsurfing (2020) About us. https://about.couchsurfing.com/about/about-us/

De Groote P, Nicasi MF (1994) Home exchange: an alternative form of tourism and case study of the Belgian market. Tour Rev 49:22–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb058147

De Keyser A, Lemon KN, Keiningham T, Klaus P (2015) A framework for understanding and managing the customer experience. Cambridge, MA

Decrop A, Degroote L (2014) Un réseau d ’ hospitalité entre Opportunisme Et idéalisme Un réseau d ’ hospitalité entre Opportunisme et idéalisme. Téoros Rev Rech en Tour 33(1):119–128. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036725ar

Decrop A, Del Chiappa G, Mallargé J, Zidda P (2018) Couchsurfing has made me a better person and the world a better place: the transformative power of collaborative tourism experiences. J Travel Tour Mark 35:57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1307159

Ding K, Choo WC, Ng KY, Ng SI (2020) Employing structural topic modelling to explore perceived service quality attributes in Airbnb accommodation. Int J Hosp Manag 91:102676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102676

Dolnicar S (2020) Sharing economy and peer-to-peer accommodation– a perspective paper. Tour Rev 76:34–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-05-2019-0197

Forno F, Garibaldi R (2015) Sharing economy in travel and tourism: the case of home-swapping in Italy. J Qual Assur Hosp Tour 16:202–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2015.1013409

Gerwe O (2021) The Covid-19 pandemic and the accommodation sharing sector: effects and prospects for recovery. Technol Forecast Soc Change 167:120733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120733

Grewal D, Levy M, Kumar V (2009) Customer experience management in retailing: an organizing framework. J Retail 85:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.01.001

Grit A, Lynch P (2011) An analysis of the development of home exchange organisations. Res Hosp Manag 1:19–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/22243534.2011.11828271

Guo Y, Wang Y, Wang C (2019) Exploring the salient attributes of short-term rental experience: an analysis of online reviews from Chinese guests. Sustainability 11:article4290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164290

Gutiérrez J, García-Palomares JC, Romanillos G, Salas-Olmedo MH (2017) The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tour Manag 62:278–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.05.003

Guttentag D (2015) Airbnb: disruptive innovation and the rise of an informal tourism accommodation sector. Curr Issues Tour 18:1192–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.827159

Hemsley B, Palmer S, Dann S, Balandin S (2018) Using Twitter to access the human right of communication for people who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Int J Speech Lang Pathol 20:50–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2017.1413137

Higuchi K (2016) KH Coder 3 Reference Manual

HomeExchange (2021) How it works. https://www.homeexchange.com/p/how-it-works-en

Huertas A, Ferrer-Rosell B, Marine-Roig E, Cristobal-Fransi E (2021) Treatment of the Airbnb controversy by the press. Int J Hosp Manag 95:102762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102762

INE-Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España (2020) Número De Turistas según comunidad autónoma de destino principal. In: Movimientos Turísticos en Front

Kastenholz E, Carneiro MJ, Marques CP, Loureiro SMC (2018) The dimensions of rural tourism experience: impacts on arousal, memory, and satisfaction. J Travel Tour Mark 35:189–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1350617

Khotimah DAK, Sarno R (2018) Sentiment detection of comment titles in booking.com using probabilistic latent semantic analysis. 2018 6th Int Conf Inf Commun Technol ICoICT 2018 0:514–519. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICoICT.2018.8528784

Kim J-H, Ritchie JRB, McCormick B (2012) Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. J Travel Res 51:12–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510385467

Knee JA (2018) Why some platforms are better than others. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 59:18–20

Kuhzady S, Çakici C, Olya H et al (2020) Couchsurfing involvement in non-profit peer-to-peer accommodations and its impact on destination image, familiarity, and behavioral intentions. J Hosp Tour Manag 44:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.05.002

Laksono RA, Sungkono KR, Sarno R, Wahyuni CS (2019) Sentiment analysis of restaurant customer reviews on Tripadvisor using naïve bayes. Proc 2019 Int Conf Inf Commun Technol Syst ICTS 2019 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTS.2019.8850982