Abstract

This paper defines the rapidly emerging mobile lifestyle of digital nomads, who work while traveling and travel while working. Digital nomadism is driven by important societal changes, such as the ubiquity of mobility and technology in everyday lives and increasingly flexible and precarious employment. Despite the growing prevalence of this lifestyle, there is a lack of common understanding of and holistic perspective on the phenomenon. The emerging literature on digital nomadism is fragmented and scattered through different disciplines and perspectives. This paper looks into digital nomadism against the array of contemporary lifestyle-led mobilities and location independent work to develop a comprehensive perspective of the phenomenon. The paper also suggests a conceptual framing of digital nomadism within lifestyle mobilities. A limited number of empirical studies on digital nomads narrows the scope of analytical discussion in this paper. Thus, the paper defines aspects and directions for further conceptualization of the phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Increasing international mobility of individuals driven by personal desires for a change in lifestyle, freedom of choice and self-fulfillment has become a worldwide trend since the 1980s. These mobilities have taken a number of forms in a variety of empirical contexts and include second-home tourism, residential tourism, seasonal and lifestyle migration, global/neo-nomadism, flashpacking, bohemian lifestyle migration and digital nomadism (Åkerlund 2013; D’Andrea 2016; Hannonen 2016, 2018; Korpela 2019; Müller 2016; O’Reilly and Benson 2009; Paris 2012; Reichenberger 2018).

The rapid growth of these mobilities is connected to socio-political factors such as globalization, individualization, increased international experiences and mobility, ease of movement, wireless communication technologies and advancement in transportation systems, the digitalization of real estate, flexibility of working lives and increases in global relative wealth (Hannonen 2018; Makimoto and Manners 1997; Müller 2016; O’Reilly and Benson 2009; Orel 2019). D’Andrea (2016) states that it is important to understand wider perspectives of globalization to assess the features of contemporary lifestyle-led mobilities and global nomadism in particular. Contemporary processes of formation of global markets, and the development of transportation and communication technologies lead to new social formations, patterns and opportunities. Indeed, the digitalization and incorporation of mobility into the everyday (both as physical relocation and technological connectivity) have resulted in the expansion of leisure and mobile lifestyles both nationally and internationally (Paris 2011; Urry 2007).

These fluid and flexible mobilities stand ‘in-between’ tourism and migration and have been collectively framed as lifestyle mobility (Åkerlund 2013; Hannonen 2016; Cohen et al. 2015). One of the most recent trends in lifestyle mobilities is digital nomadism. It resembles and contrasts other types of lifestyle-ledFootnote 1 mobilities in a number of ways. Digital nomadism is a novel mobility type that is a result of the incorporation of mobile technologies in everyday life and different types of work settings. This growing lifestyle undermines traditional sedentary perspectives and attachments to home, work and even nation-state. The mobile lifestyle of digital nomads has potentially far reaching implications for societies in terms of family life and working cultures.

Studies on digital nomadism are growing, but the term is used in a variety of, and often contradicting, ways. The emerging literature on digital nomadism is primarily focused on descriptions of their lifestyles with less attention to theoretically framing digital nomadism (Wang et al. 2018, 1). This highlights the need to develop comprehensive terminological and conceptual perspectives on digital nomadism to frame it as a proper research category and rapidly emerging mobility practice to serve future studies on the phenomenon. To address this issue the paper discusses digital nomadism through related lifestyle and work phenomena. The aim of the paper is to offer terminological and conceptual perspectives on digital nomadism.

The term “digital nomad” was introduced by Makimoto and Manners in 1997 to describe an outcome of technological advancement on people’s lives (Makimoto and Manners 1997). They predicted how mobile and portable technologies would augment work and leisure and produce a new lifestyle, in which “people are freed from constraints of time and location” (Makimoto 2013, 40). Thus, the term “digital nomad” describes a category of mobile professionals, who perform their work remotely from anywhere in the world, utilizing digital technologies, while “digital nomadism” refers to the lifestyle that is developed by these highly mobile location independent professionals.

Empirically, existing studies on digital nomads have focused on various facets of the phenomenon, positioning digital nomadism as a product of changing working cultures and other societal changes, as well as diversifying travel patterns (Müller 2016; Nash et al. 2018; Reichenberger 2018; Thompson 2018, 2019; Wang et al. 2018). These studies show a twofold approach to digital nomadism that is strongly influenced by a particular research discipline that the authors represent. They define the phenomenon either from the work life perspective or through the lifestyle angle (cf. Sect. 2). Therefore, this paper offers a critical assessment of contemporary definitions, including statistical definition of the term, in order to bridge these two angles and suggest a holistic perspective on digital nomadism.

Contemporary studies offer little conceptual framing of digital nomadism, which can be explained by the novelty of the phenomenon. Digital nomadism has been approached as a form of creative tourism (Putra and Agirachman 2016) and a type of leisure activity (Reichenberger 2018), as a novel type of location independent workforce (Orel 2019; Wang et al. 2018), and as a new economic activity and a cultural phenomenon (Wang et al. 2018) (cf. Sect. 5.1). These studies provide initial theoretical elaborations on this new phenomenon that, similar to the definition of digital nomadism, tend to take either a lifestyle or a work life perspective. Despite their one-sidedness, existing approaches offer a starting point for further conceptual developments on digital nomadism. This paper proposes further theoretical framing of the phenomenon within lifestyle mobilities through critical engagements with contemporary approaches to lifestyle-led mobilities. Theoretical conceptualisation of digital nomadism is important for understanding it as a new form of rapidly growing mobility and social phenomenon.

To achieve its objective, this paper discusses the following aspects of the phenomenon. First, digital nomadism is introduced and defined based on existing studies of the phenomenon and statistical records. To enhance the understanding of digital nomadism, it is presented and discussed through related lifestyle phenomena. Second, it is illuminated through the work-related mobilities, including the elaboration of the ‘work’ component in digital nomadism. Next, digital nomadism is reviewed through other contemporary nomadic mobilities, which simultaneously defines major features of digital nomadism. Finally, contemporary approaches to digital nomadism are discussed before the proposition of a conceptual framing of the phenomenon within lifestyle mobilities.

This paper therefore continues earlier elaborations and attempts to develop a holistic definition of digital nomadism through a comparative analysis with related phenomena and offers a conceptual framing of digital nomadism. This paper is limited to empirical evidence that originates from existing studies on digital nomads.

2 In words and numbers: approaching digital nomadism

“Marooned on a desert island, still running your business or doing your job”

(Makimoto and Manners 1997, 39)

Digital nomadism as a lifestyle phenomenon is well represented in business and professional publications. Research has been slow to acknowledge this growing mobility trend (Reichenberger 2018; Thompson 2018). As a research category, digital nomads have appeared in academic publications only during the last decade (see e.g. Makimoto 2013; Müller 2016). The number of research papers and study cases on the phenomenon in different parts of the world has been steadily growing. Contemporary studies provide various perspectives, definitions and categorizations of digital nomads but lack a coherent understanding of the term and phenomenon. This raises the relevance of the goal of this paper: to elaborate a comprehensive definition of digital nomadism.

This section discusses approaches to digital nomadism through existing empirical studies on the phenomenon. Contemporary approaches to digital nomadism can be divided into two groups: the work life perspective and the lifestyle angle. The work life perspective refers to digital nomads as a group or type of remote mobile workers. Liegl (2014, 163) calls a digital nomad “a mobile knowledge worker equipped with digital technologies to work ‘anytime, anywhere’.” Müller (2016, 344) defines digital nomads as “a new generation of location independent freelancers, young entrepreneurs, online self-employed persons.” These approaches look at digital nomadism as an outcome of changing working conditions and increases in mobile and distance work. In this perspective location independent lifestyle is secondary. Müller (2016, 344) provides a comprehensive definition of the term from a mobile work perspective, which defines digital nomads as “people who no longer rely on work in a conventional office; instead, they can decide freely when and where to work. They can essentially work anywhere, as long as they have their laptop with them and access to a good internet connection.”

The location independent work of digital nomads is accompanied by a purposeful engagement in travel. This turns remote work into a lifestyle: “Digital nomads are teleworkers who […] choose to work from everywhere, living a life of ongoing interleaved work and travel” (Wang et al. 2018, 2, 9). The authors emphasize that it is not just a new lifestyle, but a new way of performing and organizing work (Wang et al. 2018). As a lifestyle, digital nomadism is defined as “the ability for individuals to work remotely from their laptop and use their freedom from an office to travel the world” (Thompson 2019, 27). The “urge to travel” is an essential component of digital nomadism coupled with the ability to do so (Makimoto and Manners 1997, 17).

Both approaches demonstrate that employment relationships, or labor productivity in general, are an essential component of digital nomadism. Another important characteristic is international travel on a semi-permanent or ongoing basis. While the duration of travel varies significantly depending on lifestyle preferences, visa regimes and other factors, the international component has been defined as a core element of such travels (Reichenberger 2018; Thompson 2018, 2019). These two rather obvious elements are important to highlight as they are significant factors in differentiating digital nomadism from other similar phenomena that are discussed later in this paper. Digital nomads choose to be mobile and purposefully engage in international and virtual travel to work remotely in different societal and online settings.

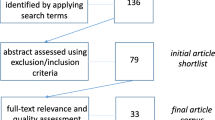

Existing studies on digital nomads have referred to statistics on self-employed workers (Thompson 2018) and co-working space users (Orel 2019) to scale the phenomenon. The difficulty of measuring the phenomenon comes from its scale, as digital nomadism spans several categories and types of employees, including both traditional and independent workers (cf. Sect. 3, Fig. 1). Reports on independent workers, freelancers and telecommuters (cf. Freelancing in America 2018; Manyika et al. 2016) do not show the scale of digital nomadism, as it is unknown how many (if any) freelancers, self-employed workers or telecommuters choose to adopt a location independent lifestyle. While these statistical records do not give an accurate representation of digital nomadism, they still indicate the rapid growth and scale of the flexible independent workforce in Western societies. Pieter Levels, the founder of the nomad list (nomadlist.com), states that every third freelancer becomes a digital nomad. He estimates that 60% of the working population will be freelancing by 2035 with the scale of digital nomadism reaching one billion people by the same year (Jacobs and Gussekloo 2016, 15). Taking into account the growing pace of freelancing, Levels’ estimations are feasible (for example, in the US freelancing has grown from 7 to 35% in 5 years, cf. Freelancing in America 2018).

Since 2018 digital nomads have been included as a separate category in the State of Independence in America annual research report. The State of Independence in America report is the first and currently only statistical estimation of digital nomadism. These reports are survey based and only provide an estimation of the phenomenon. Yet the report places digital nomadism as a growing mainstream trend that requires adequate conceptualization and definition. The 2019 survey, conducted with 3985 American residents who reflect the population demographics, states that about 4.1 million independent workers and 3.2 million traditional workers in the US currently describe themselves as digital nomads (State of Independence in America 2019). In the US alone, an additional 16.1 million Americans aspire to become nomadic someday, which indicates the extent of interest in this location independent lifestyle (State of Independence in America 2019).Footnote 2 The report claims that a significant and growing core of digital nomads is taking place in the independent workforce. Thus, with the increase in independent and remote workforce in the US and other regions of the world, digital nomadism is expected to continue to grow.

Despite the importance of these reports as a measure to frame digital nomadism, they have some shortcomings that should be noted. The two reports do not provide a uniform definition of digital nomadism. Digital nomads are defined as “people who choose to embrace a location-independent, technology-enabled lifestyle that allows them to travel and work remotely, anywhere in the world” (State of Independence in America 2018). However, reports categorize digital nomads as both intermittently mobile remote workers and ongoing travelers:

“There are digital nomads who travel for years, regularly moving across countries and continents. Others are nomadic for shorter periods, taking “workcations” and working sabbaticals lasting from several weeks to many months. […] United by a passion for travel and new adventures, digital nomads enjoy the ability to work anywhere they can connect to the Internet” (State of Independence in America 2018, 1).

These descriptions show that the State of Independence in America reports (2018, 2019) define digital nomadism as remote work with mobility as a possibility but not a condition, which does not fully align with the original understanding of the phenomenon. Makimoto and Manners (1997, 72) define digital nomadism as a further development of existing travel patterns and habits: “From the extensive, but sporadic, nomadism of today, technology’s spur could turn nomadism into a mainstream lifestyle.” This presumes that nomadism is an on-going state and a lifestyle.

Jacobs and Gussekloo (2016) state that it is impossible to define and categorize mobility of digital nomads, thus the term should rely on the self-identification of individuals as digital nomads. For this very reason the existing empirical studies on and with digital nomads are used as the main data source in this paper, as they provide first-hand information about nomads through their life stories. Emerged misconceptions in defining and categorizing digital nomads emphasize once more the need to provide a comprehensive description of this lifestyle. Thus, in order to further develop a definition of digital nomadism, it requires differentiation from other mobile individuals and non-mobile workers. The following sections discuss digital nomads along related lifestyle phenomena—flashpacking, global and neo-nomadism, and flexible work types—freelancing and telecommuting.

3 Work, travel and digital nomadism

Terminological uncertainty in defining digital nomads is growing along with studies on the phenomenon. Some authors define frequently traveled young adults as digital nomads (Richards 2015), workers or settlers of tech hubs (McElroy 2019), others use more general categories, like global nomads, that include digital nomads among others (Kannisto 2014). Digital nomads are viewed as the intersection of travel, leisure and work, and have also been referred to as mobile workers (Orel 2019), teleworkers, a hybrid of a traveling businessperson and a backpacker (Wang et al. 2018), and independent or remote workers (State of Independence in America 2018).

Some other studies on digital nomads also differentiate them into groups depending on their mobility level. For example, Reichenberger (2018) classifies digital nomads as (1) flexible workers without incorporating travel, (2) extensive travelers retaining permanent residence and (3) lifestyle movers without a place of permanent residence. In a similar vein, Toussaint (2009) distinguishes three different types of digital nomads: (1) continuous travelers who are on a continuous trip, living a life as simple as possible to save money and attempt to earn it by asking for donations or have sponsors; (2) independent workers who are fond of traveling and choose a profession that allows them to do so, conducting work through various communication techniques; (3) business travelers who travel around the world running their business, e.g. meeting clients, and find a living environment that serves their requirements for a good habitat. While all these groups are regarded by the authors as digital nomads, some of these categories are examples of teleworkers, nomads and other (im)mobile professionals. In relation to the original term, only a few of these categories can be regarded as a digital nomadic lifestyle.

Richards (2015) suggests that there are three forms of nomads nowadays: the backpacker, the flashpacker and the global nomad. The main differentiation between digital nomads and backpackers is that the latter travel for touristic or lifestyle reasons without the need to work or work odd jobs to support their journey (Mauratidis 2018). The other two categories, flashpackers and global nomads, bring some terminological confusion in relation to digital nomads and require a more detailed examination.

A flashpacker is a technology savvy backpacker, who uses technology as a connectivity tool to plan, book and execute their journeys and stay in touch with their social networks. Flashpackers use technology to stay connected online and share experiences through digital channels, such as blogs, video channels and social media sites. Their physical mobility and online/virtual connectivity are interrelated (Paris 2012). As this category of traveler connects technology and travel, they “seemingly, embody both the backpacker culture and that of the ‘digital nomad’” (Paris 2012, 1095). Flashpackers and digital nomads are overlapping phenomena, as digital nomads also share their travel experiences online (Jacobs and Gussekloo 2016). Flashpackers do not commonly make use of technology and connectivity to work while traveling, though they might do so on occasion, blurring the boundary between flashpacking and digital nomadism. Some authors use these terms as synonyms. For example, in his study on young travelers Richards (2015) concludes that flashpackers (who are synonymous with digital nomads in his study) travel an average of 62 days per year, undertaking about four trips in 5 years (Richards 2015). Such a travel pattern contradicts the empirical evidence from other studies on digital nomads that emphasize engagement in (semi)permanent or even uninterrupted travel (Nash et al. 2018; Thompson 2018, 2019). Thus, travel and the use of technology on the road does not make one a digital nomad. It requires the accomplishment of work-related tasks and professional activities while traveling.

Working on the move or location independence bridges digital nomadism with other types of flexible and location independent work, such as freelancing and telecommuting. Earlier discussion on statistical records in this paper has already distanced digital nomadism from these types of remote work. It is however important to re-examine these phenomena since freelancing and telecommuting have preceded and, to a certain extent, produced digital nomadism.

Telecommuting is defined as “a work arrangement in a traditional work setting wherein individuals spend some portion of their time away from the conventional workplace, working from home, and communicate by way of computer-based technology” (Golden and Gajendran 2019, 56). It is important to note that telecommuting is not an aspect of technologically enabled interaction from home as a distinct geographical location, but a context and a form of such interactions and connections. In other words, telecommuting fulfils the job requirement of interacting with other members, so its nature remains the same whether “they work from home as a telecommuter or from an office” (Golden and Gajendran 2019, 56). Telecommuting is related to some extent to geographical immobility that is substituted with high technological connectivity and interaction. Telecommuting is part of digital nomads’ daily job performance from various locations around the world. Thompson (2018, 3) states that digital nomadism is an extension of telecommuting and remote work:

“Remote workers, for the most part, often have a stable household in one town and work from home, or a mixture of local places. However, digital nomads take this location independence further. They travel and do so frequently; both domestically and internationally.”

Moreover, digital nomads select their location based on leisure and lifestyle considerations, rather than work or employment (Thompson 2018, 2019). Telecommuting concerns the balancing between family duties and employment, while digital nomadism is the balancing between leisure and work (Thompson 2019). Thus, digital nomads can be regarded as telecommuters who practice the location-independent lifestyle and engage in travel.

Travel is also a differentiating component between digital nomads and freelancers. The boundaries between these two categories are, however, fluid. Freelancers are defined as professionals who are self-employed predominantly by choice. They do not have a traditional job and are flexible in terms of location. Kong et al. (2019, 10) note that similar to freelancers, “digital nomads need to work with clients outside the standard nine to five work which leads to the blurring of work life boundaries” by mobile communication technologies. Freelancers do not generally pursue the lifestyle of on-going travel as digital nomads do (Freelancing in America 2018; Mauratidis 2018). Those who do, however, might also be considered digital nomads. Thus, while some digital nomads are freelancers, but not all freelancers are digital nomads (see Fig. 1).

Another important distinction should be made between traveling professionals and digital nomads. The main difference between the two is that mobility is a choice in the case of digital nomads but a working condition or requirement in the case of traveling professionals (Mauratidis 2018). The juxtaposition of digital nomadism with related phenomena of mobile work shows that neither the technologically advanced lifestyle travel of flashpackers, nor the location independent work of freelancers and telecommuting are digital nomadism. Such comparative discussion has helped to outline the main constitutive features of digital nomadism. The interrelation of the discussed categories has been summarized in Fig. 1. Differentiation between digital nomads and other categories of contemporary nomads requires additional scrutiny, as digital nomads have not been positioned within contemporary nomadic mobilities. The next section looks at various categories of nomads in more detail.

4 Nomads: global, neo-, digital

The assumption that travel is a “normal” way of life or lifestyle is not new in academic discourses (Cohen 2010). One of the very first typologies of tourists, developed by Eric Cohen (1972), defines a “drifter” and an “explorer”—the categories of travelers that are considered to be archetypes of modern travelers, such as backpackers and nomads (Cohen 2004; Richards and Wilson 2004). These archetypal travelers venture “away from the beaten track and from the accustomed ways of life of his home country,” keep some basic routines and show some involvement into host societies that they visit (Cohen 1972, 168). Nomadism has been referred to as the lifestyle of a free people that spans diverse cultures that inverses dwelling or being (cf. Kaplan 1996, 89, 91). Drifters, explorers and nomads have been positioned as alternative, independently-minded travelers, who avoid major tourist destinations and metropolitan locations (Cohen 1972, 2004; D’Andrea 2007; Kaplan 1996). Contemporary categories of nomadic travelers include global nomads, neo-nomads and digital nomads. Additional discussion in this section differentiates these groups to better define the category of digital nomads.

An analysis of studies on global and neo-nomads shows that the distinction between the terms relies on a subjective terminological choice rather than conceptual and structural differences. Authors use these terms interchangeably (see e.g. D’Andrea 2007, 2016; Naz 2017; Richards 2015). In addition to global nomads and neo-nomads, D’Andrea (2016) synonymously uses the terms of expressive and/or hypermobile expatriates.

Global/neo-nomads are “people from affluent industrialised nations who do not live permanently in a specific location but move in the global arena and make their living along the way, in the various places in which they reside” (Korpela 2019). Studies on global and neo-nomads show that they move to semi-peripheral locations of the world with favorable climates to engage in a different lifestyle. To support such a lifestyle, they seek alternative employment possibilities at the destinations, such as in entertainment, catering and wellness to get by, but in some cases do not necessarily work (D’Andrea 2007, 2016; Kannisto 2014). For these types of nomads “work is their own creation” (Kannisto 2014, 96).

In her study on design solutions for location independent professionals, Naz (2017) brings a rather contradictory perspective on neo-nomads. She uses the term “neo-nomads” to define the new class of highly mobile workers, but at the same time includes expatriates, migrants, global workers, as well as frequent travelers in this category. Ultimately, her definition of neo-nomads is closer to digital nomads: “the new-generation information technology professionals, entrepreneurs and freelancers.” It emphasizes employment at the core of this category, which, however, does not necessarily include travel (Naz 2017, 6). Such terminological uncertainty demonstrates the ambiguity of existing concepts and absence of clear-cut boundaries between different categories of travellers.

Employment relationships and the nature of work in travel separates digital nomads from other categories of contemporary nomads. Digital nomads bring their work with them, often working the prescribed office hours (Thompson 2018). While global nomads might also work, many of them do sedentary jobs to earn enough money to get by and move on (Kannisto 2014). Moreover, “contrary to digital nomads, global nomads do not necessarily use technology as the main means of their survival on the go” (Mauratidis 2018, 31). Studies show that digital nomads do not necessarily long for peripheral locations, but stay in big metropolitan centers with sufficient infrastructure, such as co-working spaces, and stable WiFi to support their working and personal routines (Nash et al. 2018; Orel 2019; Thompson 2019).

Global and digital nomads are also alike in many ways. One common feature is downshifting or departure from consumerism (D’Andrea 2016; Kannisto 2014; Nash et al. 2018). Downshifting includes practices of slow travel, alternative forms of exchange, and minimalist lifestyles. These attitudes are not necessarily as widespread among other kinds of travelers (Kannisto 2014). Empirical evidence shows that digital nomads largely rely on the sharing economy, in accommodation sector in particular. Most of the accommodation is booked through the AirBnB.com platform (Kong et al. 2019; Thompson 2018; Wang et al. 2018). The use of the platform is often two-sided, as a small proportion of digital nomads who own properties also rent them out. Unlike digital nomads, the sharing economy in accommodation choice at the destination is not a common option for global nomads (Kannisto 2014).

The life of perpetual travel of both global and digital nomads also demands a minimalistic lifestyle: “The nomads’ prime requirement is clearly portability and that means a tool stripped of all non-essentials” (Makimoto and Manners 1997, 119; see also Nash et al. 2018). This means that the quantity of possessions is limited to the amount that one can physically carry or that is permitted by airline baggage allowances. Another downshifting feature of global nomads is the prioritization of leisure over work: “They rather consume less and keep their freedom than earn more money” (Kannisto 2014, 116). Studies on digital nomads do not yet provide a comprehensive picture to support this statement. While in relation to their education and social status digital nomads are underemployed (in comparison to their settled peers), such a professional down-shift is connected to major societal changes and the precariousness of employment in Western societies (see e.g. Thompson 2018, 2019), rather than a personal choice of favoring leisure over work.

Presently it can be concluded that downshifting is present to different extents in global and digital nomadism. Global nomads as downshifters “choose to spend more time with their families, enjoy a healthier lifestyle, and do things they consider meaningful instead of just earning money and paying bills” (Kannisto 2014, 118). While a more meaningful and happier lifestyle is an integral part of digital nomadism, it is not opposed to work and labor productivity as in case of global nomads. Digital nomadism as a lifestyle is promoted by digital nomads themselves through their active online presence such as personal blogs, books and social media channels. It is portrayed as a happier and more fulfilling life of location free living and working (Jacobs and Gussekloo 2016). However, more research is needed to better address this issue in digital nomadic lifestyle.

Detachment from a nation state, its regimes and societal order is another bridging factor between global, neo- and digital nomads. The definition of nomadic lifestyle in general has always been associated with the attitude that defines and critiques the settlement, art and power of the state (Kaplan 1996). D’Andrea (2016, 100) points out that the neo-nomadic lifestyle manifests the “desire and rejection of mainstream (sedentary) societies toward countercultural (nomadic) lifestyles.” He argues that global nomads “despise homeland-centric identities” and create new forms of subjectivity and bonding based on lifestyle (D’Andrea 2016, 102). Korpela (2019) also points out that neo-nomads and lifestyle travelers “seek the company of the like-minded people” in different locations to “spend their time with people who share similar lifestyle and values.” This perspective has been gaining support also in studies on digital nomadism. Already in 1997 Makimoto and Manners predicted the loosening of nationality-based ties that would be replaced by other connections. Co-working spaces, joint nomadic unconferences, cruises and other retreats are examples of products that are developed and sustained by digital nomadism. These events and services are evidence of lifestyle-based bonding that replace other attachments and belongings, such as a traditional workplace community, residential neighborhoods and even nation states.

Emerging hotspots of digital nomads around the world, such as Chiang Mai, Thailand and Bali, Indonesia, that successfully accommodate the needs of lifestyle travelers through co-working and co-living industries are vivid examples of lifestyle-led destinations that continue to attract more digital nomads (Thompson 2018; Wang et al. 2018). These deterritorialized communities and supranational forms of togetherness of digital nomads continue the neo-nomadic tradition of anti-sedentarist perspectives towards societies.Footnote 3

Lifestyle-based bonding with like-minded people often results in the creation of ‘communities within communities’ in digital nomad destinations. Employing the example of Western lifestyle migrants in India, Korpela (2019) accurately summarizes this trend:

“instead of immersing themselves in local cultures, they move within the (Western) bohemian—alternative—space and, rather than being at home everywhere, they are with people who share their lifestyle and values. It is thus not simply migration to a specific place but migration to a specific alternative social scene that exists in various places”.

Existing empirical evidence on digital nomads supports such segregation from local people and local communities (Thompson 2018, 2019). Kannisto (2014) argues that global nomads try to immerse themselves in local cultures in their temporary locations. This, however, is questioned by the ephemeral nature of their stay at destinations, which is often pre-determined by entry regulations.

Further comparison and juxtaposition of global, neo- and digital nomads could be continued along numerous aspects of these lifestyles but they extend beyond the limits and scope of this paper. Thus, the present comparison is limited to those facets that enhance the understanding of digital nomadism. Based on existing approaches to digital nomadism and the given comparison with similar phenomena, the following definition of digital nomadism is proposed. The term ‘digital nomad' refers to a rapidly emerging class of highly mobile professionals, whose work is location independent. Thus, they work while traveling on (semi)permanent basis and vice versa, forming a new mobile lifestyle. In the following section I discuss contemporary approaches to digital nomadism and suggest a conceptual framing of the phenomenon within lifestyle mobilities.

5 Locating digital nomadism within lifestyle mobilities

5.1 Approaches to digital nomadism

A few studies present conceptual approaches to digital nomadism. These conceptual perspectives, however, tend to fragment the phenomenon, locating it either as a leisure activity or employment. Putra and Agirachman (2016) approached digital nomadism as a form of creative tourism and Reichenberger (2018) as a leisure activity, while Orel (2019) positioned digital nomads as a location independent workforce and an alternative to traditional employment. Similarly, Wang et al. (2018) proposed to look at digital nomadism as a new form of working and organizing life. Other perspectives include digital nomads as a cultural phenomenon and a new form of economic activity (Wang et al. 2018).

Putra and Agirachman (2016) define digital nomadism as a touristic activity based on novelty as a major motivation in digital nomadism. Novelty is a core motivation in tourism and travel. Indeed, digital nomads as ongoing travelers visit new destinations and create novel experiences. However, digital nomads are not tourists as “they seek out resources, which allow them to accomplish nomadic work” (Nash et al. 2018, 214). While recreation is a significant a part of their travels, it is questionable whether it is an underlying purpose of such travels (Mauratidis 2018; Orel 2019). On the other hand, unlike digital nomads, tourists and other groups of travelers, such as backpackers, also travel, but do not work. Reichenberger (2018) looks at leisure as an integral component of digital nomadism. She argues that digital nomads transfer leisure components, such as enjoyment and self-control, to their working environments and even perceive employment-related work as leisure.

The categorization of digital nomadism as an alternative and/or independent work reflects the work studies approach towards the phenomenon (Liegl 2014; Müller 2016; Wang et al. 2018). It has categorized digital nomads as a new type of independent workers and co-working space users. On the one hand, studies on co-working emphasize the significance of a sense of togetherness and community (Jackson 2017; Mouratidis 2018; Orel 2019). This perspective is important to understanding digital nomadism also as a lifestyle, in which community replace other attachments, such as place of residence, permanent office space and nationality. On the other hand, studies on co-working and telecommuting do not look into the wider mobility trajectories of individuals, including the international scale of travel and de-territorialization of work and home, which are performed by digital nomads. Digital nomads, as a modern type of mobile professionals, have been placed between digital, nomadic, gig workers and global adventure travelers, as they incorporate features of these phenomena (Nash et al. 2018; see also Fig. 1). Studies of work explicate the effects of precariousness of employment on changing working cultures (Premji 2017), which is an important aspect in understanding the production of digital nomadism. In relation to mobility, contemporary studies of work focus on two perspectives: employment related geographical mobility and the digitalization of movement though platform work and telecommuting (Bissell 2018; Cresswell et al. 2016; Golden and Gajendran 2019). These perspectives look at mobility between the fixed locations of home and work(place) with the emphasis on geographical relocation as a necessity. Thus, digital nomads are left out of the scope of research on labor mobilities as they perform “non-location based employment” (Thompson 2018, 17). At the same time work, as a part of digital nomadic lifestyle, has not been fully conceptualized in contemporary studies on digital nomads. This shows the need for further conceptual developments on work in digital nomadic mobilities.

Wang et al. (2018) suggest a theoretical framing of digital nomadism as a new economic model and a cultural phenomenon. They base this perspective on the new forms of production and consumption performed by digital nomads, such as digital work, digital platforms, and the digitalization of consumed environments. Digital nomads have been developing into a particular subculture of “journeymen” (Wang et al. 2018). They have become a specific customer segment and facilitated development of new services and products. It is important to note that destinations around the world have quickly responded to the new phenomenon and started to market themselves as digital nomad friendly—projecting themselves as ideal locales for this lifestyle segment to live and work (such as the ranking of world cities at nomadlist.com). A number of countries have established attractive taxation, visa-free stays, e-residency, and digital nomad visa schemes to welcome more temporary residents and digital nomads (such as smart visa in Thailand and digital nomad visa in Estonia). The number of emerging businesses serving the needs of this new lifestyle include (co-)living and (co-)working spaces, digital nomad house rentals (digitalnomadhouse.net), leisure programs, conferences, banking, healthcare insurance, magazines (nomadsmagazine.com) and even a nomad nation project (Digital Nomads Nation 2019). These perspectives can be further developed from economic and cultural perspectives based on the growing services, social and cultural activities targeting digital nomads. Taking into account the presented approaches to digital nomadism, I further propose a conceptualization of digital nomadism within lifestyle mobilities that embraces and addresses both travel and work components of this lifestyle trend.

5.2 Defining digital nomadism as a lifestyle mobility

Digital nomads are both a product and an example of the ubiquity of mobilities in everyday lives. As our society rapidly transforms itself into a mobile society, in which interactions are also mobilized, the “traditional segmentation of context dissolves, so private life can interrupt working life and vice versa” (Sørensen 2002, 1). Previously “discretionary” mobilities, such as tourism and recreational travel, were categorized as separate from the everyday: “travel undertaken voluntarily with the disposable income left after basic necessities of life have been covered” (Cohen and Cohen 2015, 157–158). Researchers note that nowadays travel has become an inseparable part of life, rather than a break from it (Cohen 2010). The new emerging lifestyle of digital nomads is an example of this trend, as it merges work and travel (Makimoto and Manners 1997; Nash et al. 2018).

The term “lifestyle traveller” describes individuals that engage in long-term travel as a lifestyle (Cohen 2010, 64). Cohen et al. (2015, 155) state that lifestyle-led mobility patterns break the boundaries between leisure, migration and travel as well as “conventional binary divides between work and leisure”, they also destabilize the concepts of ‘home’ and ‘away’. The lifestyle mobility framework is useful in locating various modes of travel that exist between permanent migration and temporary mobilities, such as various forms of contemporary nomadic mobilities. Lifestyle mobility is defined as “ongoing movements of varying durations”, which has “multiple moorings and has no immediate plans to return ‘home’” (Cohen et al. 2015, 162).Footnote 4 The phenomenon of digital nomadism inductively indicates its conceptual fit into this approach, as digital nomads are distinct through their “length of travel and decision not to have a home base” (Nash et al. 2018, 212).

The definition of lifestyle mobility shows that there is no intention to return (home): “lifestyle mobility pre-supposes the intention to move on, rather than move back” (Cohen et al. 2015, 159). Yet, lifestyle mobility acknowledges the existence of several ‘homes’ that are visited in a preferred manner. Thus, we must question how return is defined, apart from its differentiating condition between lifestyle mobility and other mobility types, such as lifestyle migration. By diminishing the importance of ‘one’ home lifestyle mobility overlooks the possibility of occasional visitations, such as passing through destinations or visiting friends and relatives, and other obligatory visits. ‘No return’ is indeed a rather restrictive category for defining and framing mobilities under the concept of lifestyle mobility. Empirically there are no limits of individual transition between various mobility states and concepts (between permanent, semi-permanent mobility or immobility; return or no return). If a digital nomad settles, does it mean a return home? Or could it be a transition to another research category, such as a lifestyle migrant, or a spiritual transition into a global nomad or something else? These questions require a certain degree of flexibility in the conceptual framework. Thus, considering evolving lifestyle-led mobilities, I propose to look at a possible return from the perspective of the life course rather than through seasonality or circulation between lifestyle and ‘home’ locations.

Cohen et al. (2015) propose an ideal(istic) perspective on lifestyle mobility as a freedom of travel opportunities. In fact, instead of just going anywhere, individuals move within institutionally arranged frameworks that limit their ability to choose. In this regard the issues of power geometries, inequalities of mobility and mobility regimes come to the surface and are vividly reflected in the production of digital nomadism. This perspective has long been overlooked in studies on lifestyle travelers (Cohen 2004). As discussed earlier in the paper, when engaging themselves in a state of perpetual travel, digital nomads do not and cannot completely detach themselves from home(state). The proposed freedom of mobility is often conditioned by entry and exit mobility regimes, the validity of visas and passports that define under which conditions and time periods one can visit a destination as well as exit a home country (Cohen 2004; Hannonen 2016). The latter is often tied to social security, taxation, health benefits and other national obligations. This demonstrates that while the concept of lifestyle mobilities emphasizes the freedom of mobility as one’s individual choice, it pays less attention to the significance of structures and mobility regimes (Hannonen 2016; Korpela 2019). Another largely overlooked constraint is inward confinements. A mobile lifestyle requires “competence, resourcefulness, endurance and fortitude, as well as an ability to plan one’s moves” (Cohen 2004, 45). These show that the conceptualization of lifestyle mobility still lacks a sufficient empirical base, as lifestyle-led mobilities in general, and digital nomadism in particular, have been the subject of limited academic attention (Cohen et al. 2015; Thompson 2018).

The lifestyle mobility approach originally departed from the importance of geographical relocation or corporal travel for various lifestyle choices. The mobility of digital nomads is a complex interrelation of physical relocation, the mobility of capital, objects, information, knowledge, ideas and cultural practices and also interactions, including connections at a distance and telecommuting. Various aspects and entanglements of the virtual mobilities and connections of digital nomads as well as digital and mobile work should be further conceptualized within lifestyle mobilities.

Work as a part of a location independent lifestyle is underrepresented in lifestyle mobility. Digital nomadism extends employment related geographical mobility as it combines digital and physical relocation, with the latter being a personal choice rather than an employment requirement. Cresswell et al. (2016) argue that studies of work have engaged with the growing body of mobility theory in limited ways, while mobilities studies have taken a narrow perspective towards work and employment. Cohen et al. (2015, 162) note that “whilst lifestyle mobility can include work and career, we see the dominant purpose of its associated movements as lifestyle-led rather than driven by economic gain or a logic of production. As such, a career is not a defining feature of lifestyle mobility”. On the contrary, in most cases, the time commitment of lifestyle travel entails a move away from a career-dominated way of life (Cohen 2010). The interrelationship between work and lifestyle in digital nomadism follows the proposed logic of lifestyle mobilities. While the value of labor productivity is an important feature in the lifestyle of digital nomads (Müller 2016), they do not engage in travel because of work. As shown in the downshifting discussion, career advancement is not the purpose of such mobility (Thompson 2018). Scientific discussions, however, should further engage in defining mobile work as an inseparable part of some lifestyle mobilities, such as digital nomadism.

In addition to the perspective on nomadism as a geographical relocation due to lifestyle reasons, nomadicity is also a working condition (Ciolfi and Pinatti de Carvalho 2014; Humphry 2014; Nash et al. 2018; Rossitto et al. 2014). Nomadicity in work reveals a contemporary trend of postindustrial redistribution of the material conditions that support work, which are increasingly shifted from employers to individual workers (Humphry 2014). Ciolfi and Pinatti de Carvalho 2014 define at least four perspectives on nomadicity in work settings. They include the absence of a stable location in which work is accomplished, access to information and technological resources to accomplish location and time independent work, the mobilization of resources to locations in which temporary workplaces are established and the blurring of work-life boundaries in the lives of people who engage with it (Ciolfi and Pinatti de Carvalho 2014, 129). Nomadicity as a working condition of digital nomads also includes the movement from workplace to workplace (Nash et al. 2018). This indicates the precariousness of employment and freelancing as a part of digital nomadism that have been discussed in the paper. Authors argue that the increases in technology-enabled nomadic work gives rise to other supportive environments, physical and digital forms of commons and sociability, such as co-working spaces and technology platforms. Co-working spaces are defined as shared collaborative workspaces that offer a workstation, but also cafes, events and networking opportunities (Jackson 2017; Orel 2019). Digital platforms, applications and programs are instruments and tools to find and conduct digital work and to produce digital products, while online social platforms are places for personal connections (Kong et al. 2019; Nash et al. 2018).

A theoretical discussion of digital nomadism within lifestyle mobilities enhances further understanding and framing of this lifestyle as a mobility phenomenon. While lifestyle mobilities focus on lifestyle as the main driving component of such mobilities, digital nomadism brings new facets to such discussions through its essential work-component. This raises the need for future conceptual engagements between digital nomadism and lifestyle mobilities with the support of empirical data.

6 Conclusions

The phenomenon of digital nomadism is relatively new in academic discussions. Publications on digital nomadism provided information on this emerging mobility practice and offered multiple approaches and definitions. The abundance of explications in relation to digital nomadism indicates the ambiguity of the practice itself. Thus, in light of the multiple perspectives, this paper has aimed to enhance the conceptual and terminological framing of digital nomadism. In order to do so, the paper has looked into the main differentiating factors between digital nomadism and other lifestyle-led mobilities and mobile remote work (see Fig. 1). Through a comparative discussion with related lifestyle phenomena and an analysis of existing studies on digital nomads, the main aspects of the phenomenon in question have been defined, such as the importance of labor productivity in digital nomadism, the state of international (semi)perpetual travel, downshifting, lifestyle-led bonding and communities and nomadicity of work.

Contemporary knowledge on nomadic mobilities and location independent work provides a useful but fragmented understanding of digital nomadism. Digital nomads are both highly mobile professionals and lifestyle travelers, which creates additional difficulty in framing the phenomenon. Existing studies, approaches and conceptual framings of the phenomenon tend to take either a work or leisure perspective towards digital nomads. Thus, in addition to elaborating a comprehensive definition of the term ‘digital nomad’, this paper proposes a conceptual framing of digital nomadism within lifestyle mobility approach. It also defines the importance of mobile work as an integral component of such lifestyle-led mobility. Work has yet to be included in contemporary discussions of lifestyle mobilities.

The main limitation of this paper is the lack of empirical evidence on various facets of digital nomadism to support the analytical discussion presented here. Despite this limitation, the paper establishes the direction for future conceptualization of digital nomadism. The conceptual framing of the phenomenon should further focus on the various mobile connections and relocation of digital nomads and on nomadic mobile work as a part of their lifestyle. Important issues to consider in future research on the phenomenon is the duration of nomadism: Is it a stage in life and do digital nomads settle? How is the notion of home transformed in such mobility, and where is home for a digital nomad? It is also important to assess the impact of digital nomadism on the places that they visit and eventually leave behind.

Change history

08 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-021-00205-6

Notes

For convenience I use ‘lifestyle-led mobilities’ as an umbrella term to collectively refer to the variety of mobilities that the category of ‘lifestyle mobility’ encompasses. Cohen et al. (2015) introduce and use ‘lifestyle-led mobilities’ for the same purpose.

A year earlier the number of self-identified digital nomads was 4.8 million people (State of Independence in America 2018).

It should however be noted that the institution of citizenship does not allow one to detach completely from a nation state. While the digital nomadic lifestyle is regarded as a manifestation of freedom of choice and disruption with conventional societal structures, many still keep their taxes and healthcare benefits with their home countries (Thompson 2018).

It is important to note that lifestyle mobility should not be confused with the concept of lifestyle migration. The latter concerns permanent or seasonal forms of lifestyle-led relocation. Thus, the umbrella term of lifestyle-led mobilities excludes lifestyle migration (Cohen et al. 2015).

References

Åkerlund U (2013) The best of both worlds—aspirations, drivers and practices of Swedish lifestyle movers in Malta. Gerum Kulturgeografi 2013: 2, Umeå University Umeå

Bissell D (2018) Transit life: how commuting is transforming our cities. MIT Press, Cambridge

Ciolfi L, Pinatti de Carvalho AF (2014) Work practices, nomadicity and the mediational role of technology. Comput Support Coop Work 23:119–136

Cohen E (1972) Towards a sociology of international tourism. Soc Res 39:164–182

Cohen E (2004) Backpacking; diversity and change. In: The global nomad: backpacker theory in theory and practice. Channel View Publications, pp 43–59

Cohen S (2010) Re-conceptualising lifestyle travellers: contemporary ‘drifters’. In: Hannam K and Diekmann A (eds) Beyond backpacker tourism: mobilities and experiences. Channel View Publications, pp 64–84

Cohen E, Cohen SA (2015) Beyond eurocentrism in tourism: a paradigm shift to mobilities. Tour Recreat Res 40(2):157–168

Cohen SA, Duncan T, Thulemark M (2015) Lifestyle mobilities: the crossroads of travel, leisure and migration. Mobilities 10(1):155–172

Cresswell T, Dorow S, Roseman S (2016) Putting mobility theory to work: conceptuallising employment-related geographical mobility. Environ Plan A 48(9):1787–1803

D’Andrea A (2007) Global nomads: techno and new age as transnational countercultures in Ibiza and Goa. Routledge, London

D’Andrea A (2016) Neo-nomadism: a theory of post-identitarian mobility in the global age. Mobilities 1(1):95–119

Digital Nomads Nation (2019) https://bit.ly/2zvwgDe

Freelancing in America (2018) https://www.upwork.com/press/2018/10/31/freelancing-in-america-2018/

Golden TD, Gajendran RS (2019) Unpacking the role of a telecommuter’s job in their performance: examining job complexity, problem solving, interdependence, and social support. J Bus Psychol 34:55–69

Hannonen O (2016) Peace and quiet beyond the border: the trans-border mobility of Russian second home owners in Finland. Doctoral Dissertation. Juvenes Print, Tampere. http://bit.ly/dissertation-oh

Hannonen O (2018) Second home owners as tourism trend-setters: a case of residential tourists in Gran Canaria. J Spat Organ Dyn 6(2):345–359

Humphry J (2014) Officing: mediating time and the professional self in the support of nomadic work. Comput Support Coop Work 23:185–204

Jackson L (2017) The importance of social interaction in the co-working spaces of Boston USA and London UK. In: European media managers association conference 10-12.5.2017, Ghent

Jacobs E, Gussekloo A (2016) Digital nomads: how to live, work and play around the world. Self-published. http://www.digitalnomadbook.com

Kaplan C (1996) Questions of travel. Duke University Press, Durham

Kong D, Schlagwein D, Cecez-Kecmanovic (2019) Issues in digital nomad-corporate work: an institutional theory perspective. In: Proceedings of the 27th European conference on information systems (ECIS), Stockholm and Uppsala, June 8–14, 2019. ISBN 978-1-7336325-0-8 Research Papers

Kannisto P (2014) Global Nomads: Challenges of Mobility in the Sedentary World. Tilburg University, Tilburg

Korpela M (2019) Searching for a countercultural life abroad: neo-nomadism, lifestyle mobility or bohemian lifestyle migration? J Ethn Migrat Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1569505

Liegl M (2014) Nomadicity and the care of place—on the aesthetic and affective organization of space in freelance creative work. Comput Support Coop Work 23:163–183

Makimoto T (2013) The age of digital nomad—impacts of CMOS innovation. IEEE Solid State Circuits Mag 5(1):40–47

Makimoto T, Manners D (1997) Digital nomad. Wiley, Chichester

Manyika J et al (2016) Independent work: choice, necessity and the gig economy. McKinsey Global Institute Report. http://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/labor-markets

McElroy E (2019) Digital nomads in siliconising Cluj: material and allegorical double dispossession. Urban Stud. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019847448

Mouratidis G (2018) Digital Nomadism: Travel, Remote Work and Alternative Lifestyles. Lund University, Lund

Müller A (2016) The digital nomad: buzzword or research category? Transnatl Soc Rev 6(3):344–348

Nash C, Hossein-Jarrahi M, Sutherland W, Phillips G (2018) Digital Nomads beyond the buzzword: defining digital nomadic work and use of digital technologies. In: Chowdhury G, McLeod J, Gillet V, Willet P (eds) Transforming digital worlds. Springer, Berlin, pp 207–217

Naz A (2017) Interactive living space for nep-nomads: an anticipatory approach. Doctoral Dissertation. The University of Texas at Dallas

O’Reilly K, Benson M (2009) Lifestyle migration: escaping to the good life? In: Benson M, O’Reilly K (eds) Lifestyle migrations: expectations, aspirations and experiences. Ashgate, Surrey, pp 1–13

Orel M (2019) Coworking environments and digital nomadism: balancing work and leisure whilst on the move. World Leis J 61(3):215–227

Paris C (2011) Affluence, mobility and second home ownership. Routledge, Abingdon

Paris CM (2012) FLASHPACKERS: an emerging sub-culture? Ann Tour Res 39(2):1094–1115

Premji S (2017) Precarious employment and difficult daily commutes. Ind Relat 72(1):77–96

Putra GB and Agirachman FA (2016) Urban coworking space: creative tourism in digital nomads perspective. Conference Paper: Arte-Polis 6 Int Conference 4–6.8.2016, Bandung

Reichenberger I (2018) Digital nomads—a quest for holistic freedom in work and leisure. Ann Leis Res 21(3):364–380

Richards G (2015) The new global nomads: youth travel in a globalizing world. Tour Recreat Res 40(3):340–352

Richards G and Wilson J (2004) Drifting towards the global nomad. In: Richards G, Wilson J (eds) The global nomad: backpacker theory in theory and practice. Channel View Publications, pp 3–33

Rossitto C, Bogdan C, Severinson-Eklundh K (2014) Understanding constellations of technologies in use in a collaborative nomadic setting. Comput Support Coop Work 23:137–161

Sørensen C (2002) Digital nomads and mobile services. Receiver 6

State of Independence in America (2018) Digital nomadism: a rising trend. Research brief. MBO Partners. https://www.mbopartners.com/state-of-independence/

State of Independence in America (2019) The changing nature of American workforce. MBO Partners. https://www.mbopartners.com/state-of-independence/

Thompson BY (2018) Digital nomads: employment in the online gig economy. Glocalism J Cult Polit Innov, 1–26

Thompson BY (2019) The digital nomad lifestyle: (remote) work/leisure balance, privilege, and constructed community. Int J Sociol Leis 2:27–42

Toussaint JF (2009) Home(L)essentials: the thin line between local and global identities. http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:6c123ae1-97e6-4bd6-9b4e-d15673be1672

Urry J (2007) Mobilities. SAGE, London

Wang B et al (2018) Digital work and high-tech wanderers: three theoretical framings and a research agenda for digital nomadism. Australian conference on information systems. http://www.acis2018.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ACIS2018_paper_127.pdf

Acknowledgement

Open access funding provided by University of Eastern Finland (UEF) including Kuopio University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In the original version of this article, the given and family names of Olga Hannonen were incorrectly structured.

The original article has been corrected.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hannonen, O. In search of a digital nomad: defining the phenomenon. Inf Technol Tourism 22, 335–353 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00177-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00177-z