Abstract

Background

The average life expectancy of older people is increasing, and most seniors desire to age at home and are capable of living independently. Occupational therapy (OT) is client-centered and uses patients’ meaningful activities, or occupations, as treatment methods, thus playing an important role in later adulthood. Telemedicine removes the constraints of time and space, and the combination of OT and telemedicine can greatly improve medical efficiency and clinical effectiveness.

Aims

The purpose of this scoping review was to examine the scope and effectiveness of telehealth OT for older people.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley. We searched the literature in five databases following the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design) guideline, from inception to April 2022. Two trained reviewers independently retrieved, screened, and extracted data, and used a descriptive synthesizing approach to summarize the results.

Results

The initial search yielded 1249 studies from databases and manual searches, of which 20 were eligible and were included in the final review. A thematic analysis revealed five main themes related to telehealth OT: occupational assessment, occupational intervention, rehabilitation counseling, caregiver support, and activity monitoring.

Conclusions

Telehealth OT has been used widely for older people, focusing primarily on occupational assessment and intervention provided conveniently for occupational therapists and older clients. In addition, telehealth OT can monitor patients’ activities and provide rehabilitation counseling and health education for the elderly and their caregivers, thus improving the security of their home life and the efficacy of OT. During the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth will be an effective alternative to face-to-face modalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Later adulthood is the period of life in people older than 65 years of age, according to the United Nations. Data show that the global population aged 65 and over was 727 million in 2020, and the proportion of older adults is expected to increase from 9.3 in 2020 to 16% in 2050 [1]. The satisfaction of people’s material needs and advancements in medicine are increasing the average life expectancy year by year. Population health is improving globally, with the global average life expectancy at birth having increased from 66.8 years in 2000 to 73.4 years in 2019, and with healthy life expectancy at birth having improved from 58.3 years in 2000 to 63.7 years in 2019 [2]. However, the growth rate of healthy life expectancy is significantly lower than that of life expectancy, which means that gerontology is poised to face new opportunities and challenges. Sarcopenia, malnutrition and osteoporosis are common factors leading to impairments in older adults, which in turn may result in functional limitations and disabilities [3, 4]. For example, sarcopenia in older people may lead to decreased oropharyngeal function, which can lead to malnutrition and further impair functional activity. These impairments which occur in later adulthood can reduce their quality of life and well-being, while at the same time increasing the burden on families.

Occupational therapy (OT) is an important component of rehabilitation that promotes functional independence through meaningful occupations and purposeful activities to enhance occupational performance. According to the fourth edition of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process (OTPF-4) [5], common types of OT interventions are occupation-based activities, interventions to support occupations, education and training, advocacy, group interventions, and virtual interventions. In general, OT interventions traditionally are conducted in hospitals [6], communities [7], and homes [8] through face-to-face meetings between therapists and clients. The practice of geriatrics relies on a multidisciplinary team to best serve patients, and OT plays an irreplaceable role in geriatric care [9,10,11]. Increasingly, older people are choosing to age in place, which means living independently or with minimal support in their homes [12, 13]. The focus of geriatric OT should be on helping older persons remain active and engaged in their meaningful activities and occupations while focusing on fall prevention and other safety issues in the home and community [5, 11]. However, the majority of older people with functional impairments have no access to timely occupational interventions because they have limited traditional rehabilitation resources [14]. Furthermore, older people have difficulty adhering to traditional rehabilitation because of its high cost, the time spent travelling between rehabilitation facilities and their home, and the safety issues that result from the journey [15, 16].

Fortunately, the use of mobile devices can somewhat alleviate the medical pressures of ageing [17,18,19]. Activity and participation are core concepts of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and are the central focus of OT [20, 21]. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) defines telehealth as “the application of evaluative, consultative, preventative, and therapeutic services delivered through telecommunication and information technologies” [22]. The World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) has stated that telehealth can be used as an appropriate service delivery model for occupational therapists(OTs) and may be able to improve access to OT services [23]. Telehealth was highlighted as a rapidly developing service model for OT in 2014 [24].

One study has suggested that telehealth OT could positively impact the activities and lives of adults coping with long-term disabilities [25]. As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has intensified, some OTs have been forced to transition from traditional face-to-face services to telehealth [22]. OT is for people who have functional impairments, mostly affected by chronic illnesses that are not life-threatening [26]. The lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic substantially restricted OT practice. So it’s time to think about existing OT practice and integrate it with telehealth models. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the quality of life and function of older people has declined [27, 28], and the implementation of geriatric care has been challenged [29,30,31]. A systematic review has presented experiences and reflections on telehealth in OT during the COVID-19 pandemic [32].

The OT focus on a client-centered approach, combined with the advantages of telehealth, could further develop the value of both modalities in older people. Consequently, this study had the following objectives: (a) to elucidate the areas of geriatric rehabilitation in which telehealth OT can be effectively applied; (b) to determine whether telehealth OT can fulfill the dual roles of OT and telemedicine; and (c) to analyze the current problems of telehealth OT and identify the vision for its future development.

Methods

For this study, we applied the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [33] for a scoping review and strictly followed the five basic stages: (a) identifying the research question; (b) identifying relevant studies; (c) selecting studies; (d) charting the data; and (e) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. The sixth stage, consulting with stakeholders, was omitted from this scoping review.

A scoping review, as opposed to a systematic review, was appropriate because the areas of telehealth OT in older people are unclear, the interventions are complex and diverse, and the literature is limited. For reporting this review, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [34]. The scoping review protocol was established prior to the start and was rigorously implemented at all stages.

Eligibility criteria

The search strategy was formulated using the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design) framework. This scoping review encompassed studies that met all of the following defined inclusion criteria.

Population: participants ≥ 65 years old, or include a wider age but with a mean or median age of 65 years old and older;

Intervention: focus on OT or OT-related interventions and which were conducted through telehealth;

Comparison: could be any (such as conventional face-to-face OT) or none;

Outcome: included (but were not limited to) the scope and effectiveness of telehealth OT;

Study design: all studies besides review articles which were published in English language papers in peer-reviewed journals.

Furthermore, studies were excluded if they were:

-

(i) Full-text articles that could not be found/accessed;

-

(ii) Study designs and protocols;

-

(iii) Articles on telehealth device development and platform construction and lacked a clinical evaluation.

In contrast to systematic reviews, studies that met the inclusion criteria were included in this scoping review without considering the literature quality and the journal impact factor.

Information sources

This study searched five databases for literature from the time of database inception to April 2022, in PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. This scoping review used a complete search strategy that employed keywords, US National Library of Medicine medical subject headings (MeSH) or terms related to key concepts, and the Boolean terms “AND” and “OR.” The search strategy was drafted by the first author and finalized after discussion and revision by our research team. Furthermore, relevant reviews and references of included studies were manually screened for additional suitable studies. If necessary, the original authors were contacted for further information.

Search

The key search terms included three categories related to older people, telehealth, and occupational therapy. As an example, the detailed search strategy of PubMed is presented in Table 1.

Selection of sources of evidence

Search results were imported into a citation management software package (Endnote 20), and duplicates were removed by a combination of the removal function on Endnote and a manual check by the first author. Subsequently, two trained reviewers with medical research experience of more than 5 years independently screened the titles and abstracts and then the full-text. Before the formal study, we tested the suitability of the inclusion and exclusion criteria in a pilot project of 50 studies. According to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [35], an agreement of 75% demonstrates the satisfactory performance of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The agreement between the two reviewers for the pilot was 88% and therefore our inclusion/exclusion criteria met the feasibility criteria. Any disputes were discussed and consensuses were reached among the reviewers. Other inextricable conflicts were resolved by a medical professor reviewer.

Data charting process

The first author initially drew a data extraction chart, and each author independently tested its feasibility through a pilot of five studies. Next, the standardized data extraction chart was finalized through communication and discussion by our research team. In the data extraction phase, two reviewers extracted data independently using the standardized data extraction chart, via Microsoft Excel. Any conflicts were resolved through discussion or consultation with the professor reviewer.

Data items

The data were extracted in two parts: part one: basic characteristics of the included studies, and part two: characteristics related to telehealth OT. The first part involved authors, year of publication, country of origin, study design, population group(s), age, number of study participants, intervention period, intervention frequency, and study aim(s). The second part contained the project name, telerehabilitation platform(s), and telehealth OT content(s).

Synthesis of results

The data extracted from the articles were entered into Microsoft Excel for classification and synthesis. The inevitably heterogeneous nature of data reporting in a scoping review rendered a quantitative analysis unsuitable, so we used a descriptive synthesizing approach to summarize the results in this study.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

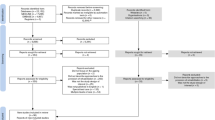

From the five databases and manual searches, 1249 studies were identified, and 778 references remained after duplicates were removed. Ultimately, 20 eligible studies were included in the review, following title/abstract and full-text screening. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram used to identify eligible studies [36].

Characteristics of sources of evidence

The 20 references ultimately included in the study were published between 2008 and 2021, and only one had been published more than 10 years previously [37]. Eight of the 20 (40%) [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] were published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A large proportion of the studies were conducted in the U.S.A. (n = 5, 25%) [39, 40, 42, 44, 46], Canada (n = 4, 20%) [47,48,49,50], and Austria (n = 4, 20%)[37, 51,52,53], with the remaining study locations being China (n = 2, 10%)[41, 43], Spain (n = 2, 10%)[45, 54], England (n = 1, 5%)[55], Israel (n = 1, 5%)[56] and Sweden (n = 1, 5%)[38]. Five studies included older persons with stroke (25%) [38, 39, 42, 46, 50], four studies included older people without special diseases (20%) [44, 51, 52, 55], two studies included older persons with Parkinson’s disease (10%) [37, 53], two studies included older people with cognitive impairment (10%) [41, 48], and two studies included older individuals with hip fracture (10%) [43, 45]. In addition, four studies included older persons from other populations of individuals who: were manual wheelchair users [49], had the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [54], had acquired brain injury [56], or had cancer [40]. Sample sizes of the studies ranged from two participants to 205 participants, and the study periods ranged from 3 weeks to 3 months. Table 2 presents the detailed characteristics of the studies we investigated.

Telerehabilitation platform(s)

Most of the studies took practicality and convenience into consideration when selecting telehealth platforms. Five studies conducted telemedicine via smartphones [39, 41,42,43, 46], seven conducted telemedicine via tablet computers [39, 43, 44, 47, 49,50,51], and seven provided intervention via video conferencing [40, 41, 48, 51,52,53, 56]. In addition, two of the studies mentioned having used other electronics, such as a computer [54] or an interactive whiteboard [51].

The development of new platforms/applications

Specific applications (APPs) or platforms were applied in 12 of the studies to study the value and efficacy of a newly developed software package or platform [38, 39, 42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 50, 54, 55].

Characteristics related to telehealth OT

A thematic analysis revealed five main themes that were related to telehealth OT: occupational assessment, occupational intervention, rehabilitation counseling, caregiver support, and activity monitoring. Detailed characteristics related to telehealth OT are presented in Table 3, and the correlations between the themes included in the literature are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Occupational assessment

OT begins with assessment and ends with assessment, making an accurate and efficient assessment crucial to the process of OT. Nine of the studies (45%) dealt specifically with the occupational assessment [37, 44, 46, 49, 50, 52,53,54,55]. Chumbler and colleagues used the STeleR (short for “stroke telerehab”) intervention through home visits conducted by trained occupational assistants via telehealth to assess physical performance, to provide suitable interventions for the clients. Middle and final assessments were conducted by telephone in their study [46]. Guideomeasure-3D is a web-enabled 3D mobile APP designed by Hamm et al. that enables the elderly to carry out self-assessment tasks [55]. Home modifications are effective interventions for improving older adults’ safety and independence. Nguyen et al. developed a mobile APP that provides home assessments and modifications for OTs and community-dwelling older adults [44]. Two studies focused on patients with Parkinson’s disease and confirmed the feasibility of telehealth assessment: Hoffmann assessed activities of daily living (ADL) and hand function via an Internet-based telerehabilitation system [37], and Stillerova screened cognition using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment via videoconferencing [53]. Khan et al. assessed and diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease via videoconferencing [52]. In addition, three studies exploring the efficacy of telehealth OT [49, 50, 54] conducted assessments by telehealth.

Occupational intervention

The use of occupational-based activity is the most extensive intervention method of telehealth OT, and 15 (75%) of the included studies applied OT to telemedicine [38,39,40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 56]. OT is a client-centered discipline that reflects the establishment of occupational goals and a selection of interventions. In the studies we reviewed, goals were set using the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), and in four studies meaningful occupational interventions were selected through telehealth methods [38, 39, 48, 54]. EPIC WheelS is a training program APP for at-home instruction in wheelchair use, and it includes video instruction, self-paced training activities, and training games. It was developed to improve patients’ wheelchair skills, and in so doing to enhance their participation in the community [47, 49]. The STeleR intervention focuses specifically on improving functional mobility via in-home messaging devices and telephones [46]. The Caspar Health e-system was designed for older adults who have recently had hip fracture surgery, to engage them in occupation-based activities anywhere through digital communication [43]. The mRehab system delivers 12 mRehab activities that are designed to improve upper limb mobility in patients with chronic stroke [42]. In one study, OTs provided safety education on fall prevention and personalized home modifications through @ctivehip [45]. The Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) approach is a metacognitive approach. Pugliese et al. [50] and Beit Yosef et al. [56] used the CO-OP intervention via video conferencing in their studies. Conventional occupational interventions were used to examine the feasibility of telehealth via tablets or telephones in three studies [40, 41, 51].

Rehabilitation counseling

OT focuses on the meaningful activity/occupational performance of clients, so providing rehabilitation consultations to clients is a significant part of telehealth OT. However, only three papers in this review (15%) included rehabilitation consultations [43, 47, 54]. A study of the EPIC WheelS APP [47] mentioned consultations about using wheelchairs for the elderly, and the Caspar Health e-system[43] provides in-home rehabilitation consultations for patients with hip fractures. Patient Briefcase [54] is telemedicine videoconferencing equipment that provides training and counseling on energy conservation techniques that OTs use for COPD clients. Telehealth increases the continuity of early consultation and intervention, putting OT into patients’ daily lives.

Caregiver support

The clients of OT are patients who have limitations in everyday activities, and their caregivers. The use of telehealth makes caregiver support more convenient and efficient, and five of the studies we reviewed specifically involved caregiver support (25%) [40, 41, 45, 49, 51]. Crotty’s study enrolled patients and their caregivers and fully considered the application of caregiver support in telehealth [51]. A pilot study of EPIC WheelS took safety factors into account and invited caregivers to participate in the process of providing safety education [49]. Both older persons with cancer and their caregivers endure significant burdens, and some research on older adults with cancer and their caregivers has aimed to determine the feasibility and acceptability of occupation-based activities [40]. In addition, although the COVID-19 pandemic has seriously further affected patients’ access to rehabilitation, telehealth is an attractive alternative to in-person rehabilitation. Specifically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, research has shown that telehealth can provide interventions and support to patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers, and it has also addressed telehealth’s distance limitations and ability to improve patient and caregiver well-being [41]. In one study, caregivers were invited to participate in the telerehabilitation group (@ctivehip) for client management and home satisfaction [45].

Activity monitoring

Electronic devices make activity monitoring more convenient, and nine of the studies (45%) monitored occupational interventions through telehealth platforms that improved security and facilitated OTs’ ability to review and summarize their interventions [38,39,40, 46, 47, 49,50,51, 54]. OTs monitor participants’ activities weekly by in-home messaging devices, which provide feedback in a positive form to enhance the clients’ exercise adherence [46]. The EPIC WheelS APP enables therapists to monitor each client’s training activity and adjust the next session of intervention on the basis of the feedback results [47, 49]. In the research of Crotty et al., the APP named Fitbit was used to monitor activities, and BandiCam was used to record the content of videoconferences to acquire immediate feedback [51]. Patient Briefcase, the home-based supervised training system, includes a camera installed in the participant’s home to follow movements around the home and uses a pulse oximeter to monitor saturation and training sessions [54]. The F@ce platform has three interfaces: the administrator’s view, the team’s review, and the participant’s view. In the work by Guidetti et al., researchers logged into the administrator’s view to monitor the intervention process, and therapists entered the team view to monitor their patients’ occupational performances [38]. Some self-monitoring approaches also can be provided, such as the physical activity diary and wristband pedometer to enhance functional recovery discussed in Lafaro et al.’s study [40]. In addition, two of the studies monitored patients’ ADLs with the use of a messaging system embedded in the telehealth system that they studied. If the participant failed to complete the activities as required, after an extended period the therapist would receive a system reminder and then would contact the participant by telephone or other means to assure his/her safety and identify the reasons why the participant was not accomplishing the required activities [39, 50].

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This scoping review sought to identify which fields of telehealth OT can be applied to older adults and to explore the feasibility and directions of development for telehealth OT. To our knowledge, our review is the first study to combine telehealth and OT in geriatric rehabilitation. In this study we examined five areas of telehealth OT among older people: occupational assessment [37, 44, 46, 49, 50, 52,53,54,55], occupational intervention [38,39,40,41,42,43, 45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 54, 56], rehabilitation counseling [43, 47, 54], caregiver support [40, 41, 45, 49, 51], and activity monitoring [38,39,40, 46, 47, 49,50,51, 54]. The records that were included in this review provide insights into the characteristics of telehealth OT in older people and offer new ideas and novel perspectives for further research on telehealth OT.

Nineteen of the studies we reviewed were published in the past decade (95%), and only one was published more than 10 years ago [37]. In light of the COVID-19 crisis, OTs somewhere are thinking about switching from working face-to-face to using a telehealth modality. Eight of the records (40%) [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] were published after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which greatly accelerated the development of telehealth OT in a sense. Unfortunately, only one study [41] examined the protective impact of telehealth OT on older persons with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. The reasons for this limited consideration may be the time-consuming nature of clinical studies and the long publication cycle of papers. A number of preventive measures have been applied to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 infection, such as lockdown, quarantine and social distancing, but they have also brought a significant impact on the conventional medical practice and health practitioners. Since the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing number of health workers, including OTs, have been recognizing the advantages of telemedicine, and it is believed that in the near future telehealth OT will be widely adopted for older persons.

A study published in 1962 proposed the idea of mobile health services for migrant families [57], and a pilot study of the Tele-Home health project began in 1996 as a multidisciplinary team intervention that included OTs [58]. The concept of telerehabilitation actually dates back to at least 1998, when it was first used to evaluate in-home seating and home accessibility [59]. Therefore, the concept of telehealth OT is not a completely new research direction and has been studied for many years [60]. Previous reviews on telehealth focused primarily on rehabilitation for common geriatric diseases and proved the feasibility and efficacy of telerehabilitation for certain diseases in older patients, such as stroke [61,62,63], polytraumas [64], cancer [65,66,67], osteoarthritis [68], fractures [69], Parkinson’s disease [70], psychological disorders [71], and fall prevention [72, 73]. Several other studies have demonstrated the value of telerehabilitation in improving functional impairment by promoting ADLs [74] and improving lower extremity dysfunction [75]. In addition, previous research hotspots have included home health monitoring [76,77,78], telehealth assessments [79], and caregiver support [66].

In general, all of the studies that were included in this scoping review confirmed the effectiveness and clinical value of telehealth OT, with five studies [41, 43, 45,46,47] showing that interventions by telehealth were more effective than the traditional approach. The reasons for those results are probably related to three factors: the intervention environment, activity monitoring, and caregiver support. Environment is a significant factor affecting clients’ occupational performance, according to the Person-Environment-Occupation (PEO) model [80]. Most of the traditional OT assessments and interventions are carried out in specialized areas. Older adults are less adaptable to their environment and are prone to stress responses in unfamiliar environments, and those reactions affect their occupational performance [81,82,83]. In contrast, telehealth occupational interventions are conducted in the patients’ homes or communities, thus minimizing the impact of having to adapt to the environment. In addition, the long-term efficacy and safety of the treatment are also considerations for older people when choosing a treatment option. No serious adverse events were reported in any of the studies we included, so the safety of telehealth OT can be initially confirmed. Follow-up was less discussed in the included studies. Two studies [46, 56] conducted follow-up assessments at 3 months after intervention and showed that most of the improvement was maintained during the subsequent 3 months. The results of the follow-up in another study [43] showed that 3 weeks after the intervention ended the functioning of the telehealth group decreased and that of the control group remained. We are looking forward to further high-quality studies in the future.

Another advantage of telehealth OT is the ability to monitor activities comprehensively with mobile devices. As one advantage, such monitoring can improve the safety of clients’ activities. In addition, therapists can receive timely feedback and conduct their intervention processes even when their older adult patients have not participated in an occupation for a long time or the quality of the occupation has deteriorated [39, 50]. Furthermore, the impact of caregivers on older people falls within the scope of the human environment, according to the PEO model [80]. Certainly caregivers, as the people most familiar with and connected to the patients, play an especially important role in the daily lives of older people [84,85,86,87]. Because telehealth is family centered or community-centered, its advantages may be exploited to the fullest [88,89,90].

It is noteworthy, however, that in the study by Burton and O’Connell [48], telehealth OT was found to be effective but was not as effective as face-to-face occupational interventions were. We propose three likely reasons for such findings. First, the human environment is an important factor affecting occupational performance. In addition to their caregivers, the other participants surrounding older people are also of great significance, so group therapy is an efficient modality [91,92,93,94] that can increase the communication between clients and others and further restore their social abilities to participate through group activities. However, Burton and O’Connell’s study did not involve communication with anyone other than the caregivers, and that might have affected patient performance to some extent. Second, face-to-face intervention enables the clients to better obtain various forms of sensory feedback from therapists and the surrounding environment, such as through their auditory sense, tactile sense, and proprioceptive sense, but those senses are not available in telehealth, meaning that telehealth could not provide the patients with timely sensory feedback. In addition, the intervention with clients was through video recordings, which made it impossible for the clients to receive timely feedback in the intervention process, in contrast to studies in which the therapists regularly monitored activities [42, 45, 47, 49, 50]. Finally, some older adults have used mobile devices only very infrequently in the past, making it difficult for them to accept and master the use of telehealth platforms quickly. Although some studies mentioned offering training in the use of mobile devices before the interventions [39, 42, 46, 47, 49, 51, 55], it can be difficult for short-term teaching to change one’s inherent habits, especially for older people with memory degradation [95] and a reduced acceptance of novelty. In summary, these factors may have an impact on the effectiveness of telehealth OT, and thus it is necessary to further optimize the modality.

The focus of OT services is to improve a person's independence and a client's quality of life. OT practitioners supported by the philosophy of profession can work with clients of all ages, abilities and in many different settings[5]. We may frequently see OTs in hospitals, schools, nursing homes, communities and other unexpected locations. OT is an essential part of a rehabilitation group and plays an integral role in many different areas, such as neurological rehabilitation, pulmonary rehabilitation, musculoskeletal rehabilitation, and others. Furthermore, OTs are well suited to succeed as driving rehabilitation specialists[96], and are specialized in pain management[97] and sleep management[98].

Future research should focus on the following needs. First, it is essential that large-scale randomized controlled trials of telehealth OT among older adults be conducted, and also that the scope and forms of telehealth OT, such as group interventions and psychological interventions, be further explored. Finally, the application of telehealth OT should be fully explored in different lifespan, different areas and different locations of clients.

Limitations

Certain limitations merit attention because they may have influenced the results this review obtained. Initially, although we followed the PRISMA-ScR to ensure the scientific nature of the research, publication bias and selection bias are limitations for a majority of scoping reviews. Additionally, only studies published in English and with full text available were enrolled in our review. Therefore, many studies that might have been otherwise suited to our inclusion criteria were not included because they had been published in other languages. Finally, the inclusion criteria required that the studies’ participants be an average or median age of 65 years or older, thus resulting in bias caused by age inconsistency among some of the participants studied.

Conclusions

In the present study, we used a scoping review to clarify the scope and effectiveness of telehealth OT among older adults. The results reveal that telehealth OT has been used successfully for occupational assessment, occupational intervention, rehabilitation counseling, caregiver support, and activity monitoring through multiple mobile platforms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review that combines telehealth and OT in geriatric rehabilitation. Telehealth has extensive potential for use and further development, both during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Further research is needed that will employ large-scale randomized controlled trials to explore new scope and applications for telehealth OT.

References

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2021) World population ageing 2020 highlights. United Nations, New York, NY. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/world-population-ageing-2020-highlights. Accessed 20 Nov 2020

World Health Organization (2021) World health statistics 2021: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027053. Accessed 20 May 2021

de Sire A, Ferrillo M, Lippi L et al (2022) Sarcopenic dysphagia, malnutrition, and oral frailty in elderly: a comprehensive review. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14050982

de Sire A, de Sire R, Curci C et al (2022) Role of dietary supplements and probiotics in modulating microbiota and bone health: the gut-bone axis. Cells. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11040743

American Occupational Therapy Association (2020) Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process-Fourth Edition. Am J Occup Ther 74(Supplement_2):7412410010p7412410011–7412410010p7412410087. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001.

Cuevas-Lara C, Izquierdo M, Gutiérrez-Valencia M et al (2019) Effectiveness of occupational therapy interventions in acute geriatric wards: a systematic review. Maturitas 127:43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.06.005

Estrany-Munar MF, Talavera-Valverde M, Souto-Gómez AI et al (2021) The effectiveness of community occupational therapy interventions: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063142

Bennett S, Laver K, Voigt-Radloff S et al (2019) Occupational therapy for people with dementia and their family carers provided at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 9:e026308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026308

Williams LS, Lowenthal DT (1995) Clinical problem-solving in geriatric medicine: obstacles to rehabilitation. J Am Geriatr Soc 43:179–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06386.x

Ellis G, Sevdalis N (2019) Understanding and improving multidisciplinary team working in geriatric medicine. Age Ageing 48:498–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz021

Fields B, Rodakowski J, Jewell VD et al (2021) Unpaid caregiving and aging in place in the United States: advancing the value of occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.044735

Choi YJ (2022) Understanding aging in place: home and community features, perceived age-friendliness of community, and intention toward aging in place. Gerontologist 62:46–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab070

Ouden WV, van Boekel L, Janssen M et al (2021) The impact of social network change and health decline: a qualitative study on experiences of older adults who are ageing in place. BMC Geriatr 21:480. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02385-6

Bayley MT, Hurdowar A, Richards CL et al (2012) Barriers to implementation of stroke rehabilitation evidence: findings from a multi-site pilot project. Disabil Rehabil 34:1633–1638. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2012.656790

Tung Y-J, Lin W-C, Lee L-F et al (2021) Comparison of cost-effectiveness between inpatient and home-based post-acute care models for stroke rehabilitation in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:4129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084129

Tummers JFMM, Schrijvers AJP, Visser-Meily JMA (2012) Economic evidence on integrated care for stroke patients; a systematic review. Int J Integr Care 12:e193–e193. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.847

Gettel CJ, Chen K, Goldberg EM (2021) Dementia care, fall detection, and ambient-assisted living technologies help older adults age in place: a scoping review. J Appl Gerontol 40:1893–1902. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211005868

Ho A (2020) Are we ready for artificial intelligence health monitoring in elder care? BMC Geriatr 20:358. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01764-9

O’Brien K, Liggett A, Ramirez-Zohfeld V et al (2020) Voice-controlled intelligent personal assistants to support aging in place. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:176–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16217

Pettersson I, Pettersson V, Frisk M (2012) ICF from an occupational therapy perspective in adult care: an integrative literature review. Scand J Occup Ther 19:260–273. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2011.557087

Larsson-Lund M, Nyman A (2017) Participation and occupation in occupational therapy models of practice: a discussion of possibilities and challenges. Scand J Occup Ther 24:393–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2016.1267257

American Occupational Therapy Association (2018) Telehealth in occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther 72(Supplement_2):7212410059p1–7212410059p18. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.72S219.

World Federation Of Occupational Therapists (2014) World Federation of occupational therapists' position statement on telehealth. Int J Telerehabil 6:37–39. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2014.6153.

Cason J (2014) Telehealth: a rapidly developing service delivery model for occupational therapy. Int J Telerehabil 6:29–35. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2014.6148

Beit Yosef A, Jacobs JM, Shames J et al (2022) A performance-based teleintervention for adults in the chronic stage after acquired brain injury: an exploratory pilot randomized controlled crossover study. Brain Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020213

Ganesan B, Fong KNK, Meena SK et al (2021) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on occupational therapy practice and use of telerehabilitation—a cross sectional study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 25:3614–3622. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202105_25845

Walle-Hansen MM, Ranhoff AH, Mellingsæter M et al (2021) Health-related quality of life, functional decline, and long-term mortality in older patients following hospitalisation due to COVID-19. BMC Geriatr 21:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02140-x

Salman D, Beaney T, Catherine ER et al (2021) Impact of social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic on the physical activity levels of adults aged 50–92 years: a baseline survey of the CHARIOT COVID-19 rapid response prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 11:e050680. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050680

Crosignani S, Fantinati J, Cesari M (2021) Frailty and geriatric medicine during the pandemic. Front Med 8:673814. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.673814

Clarfield AM, Dwolatzky T (2021) Age and ageing during the COVID-19 pandemic; challenges to public health and to the health of the public. Front Public Health 9:655831. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.655831

Ischia L, Naganathan V, Waite LM et al (2021) COVID-19 and geriatric medicine in Australia and New Zealand. Australas J Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.13027

Dahl-Popolizio S, Carpenter H, Coronado M et al (2020) Telehealth for the provision of occupational therapy: reflections on experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Telerehabil 12:77–92. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2020.6328

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method Theory Pract 8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC et al (2020) Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 18:2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-20-00167

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Hoffmann T, Russell T, Thompson L et al (2008) Using the Internet to assess activities of daily living and hand function in people with Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 23:253–261. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2008-23307

Guidetti S, Gustavsson M, Tham K et al (2020) F@ce: a team-based, person-centred intervention for rehabilitation after stroke supported by information and communication technology—a feasibility study. BMC Neurol 20:387. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01968-x

Kringle EA, Setiawan IMA, Golias K et al (2020) Feasibility of an iterative rehabilitation intervention for stroke delivered remotely using mobile health technology. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 15:908–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2019.1629113

Lafaro KJ, Raz DJ, Kim JY et al (2020) Pilot study of a telehealth perioperative physical activity intervention for older adults with cancer and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer 28:3867–3876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05230-0

Lai FH, Yan EW, Yu KK et al (2020) The protective impact of telemedicine on persons with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 28:1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.019

Langan J, Bhattacharjya S, Subryan H et al (2020) In-home rehabilitation using a smartphone app coupled with 3d printed functional objects: single-subject design study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8:e19582. https://doi.org/10.2196/19582

Li CT, Hung GK, Fong KN et al (2020) Effects of a home-based occupational therapy telerehabilitation via smartphone for outpatients after hip fracture surgery: a feasibility randomised controlled study. J Telemed Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X20932434

Nguyen AT, Somerville EK, Espín-Tello SM et al (2020) A mobile app directory of occupational therapists who provide home modifications: development and preliminary usability evaluation. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 7:e14465. https://doi.org/10.2196/14465

Ortiz-Pina M, Molina-Garcia P, Femia P et al (2021) Effects of tele-rehabilitation compared with home-based in-person rehabilitation for older adult’s function after hip fracture. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105493

Chumbler NR, Quigley P, Li X et al (2012) Effects of telerehabilitation on physical function and disability for stroke patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 43:2168–2174. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646943

Giesbrecht EM, Miller WC (2017) A randomized control trial feasibility evaluation of an mHealth intervention for wheelchair skill training among middle-aged and older adults. PeerJ 5:e3879. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.3879

Burton RL, O’Connell ME (2018) Telehealth rehabilitation for cognitive impairment: randomized controlled feasibility trial. JMIR Res Protoc 7:e43–e43. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.9420

Giesbrecht EM, Miller WC, Jin BT et al (2015) Rehab on wheels: a pilot study of tablet-based wheelchair training for older adults. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2:e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/rehab.4274

Pugliese M, Ramsay T, Shamloul R et al (2019) RecoverNow: a mobile tablet-based therapy platform for early stroke rehabilitation. PLoS ONE 14:e0210725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210725

Crotty M, Killington M, van den Berg M et al (2014) Telerehabilitation for older people using off-the-shelf applications: acceptability and feasibility. J Telemed Telecare 20:370–376. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X14552382

Martin-Khan M, Flicker L, Wootton R et al (2012) The diagnostic accuracy of telegeriatrics for the diagnosis of dementia via video conferencing. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13:487.e19-487.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.03.004

Stillerova T, Liddle J, Gustafsson L et al (2016) Could everyday technology improve access to assessments? A pilot study on the feasibility of screening cognition in people with Parkinson’s disease using the montreal cognitive assessment via Internet videoconferencing. Aust Occup Ther J 63:373–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12288

Rosenbek Minet L, Hansen LW, Pedersen CD et al (2015) Early telemedicine training and counselling after hospitalization in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a feasibility study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-014-0124-4

Hamm J, Money AG, Atwal A (2019) Enabling older adults to carry out paperless falls-risk self-assessments using guidetomeasure-3D: a mixed methods study. J Biomed Inform 92:103135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103135

Beit Yosef A, Jacobs JM, Shenkar S et al (2019) Activity performance, participation, and quality of life among adults in the chronic stage after acquired brain injury-the feasibility of an occupation-based telerehabilitation intervention. Front Neurol 10:1247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01247

Darrah W (1962) A mobile health service for migrant families. Nurs Outlook 10:172–175

Johnston B, Wheeler L, Deuser J (1997) Kaiser permanente medical center’s pilot tele-home health project. Telemed Today 5:16–17, 19

Burns RB, Crislip D, Daviou P et al (1998) Using telerehabilitation to support assistive technology. Assist Technol 10:126–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400435.1998.10131970

Hung Kn G, Fong KN (2019) Effects of telerehabilitation in occupational therapy practice: a systematic review. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 32:3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1569186119849119

Sarfo FS, Ulasavets U, Opare-Sem OK et al (2018) Tele-rehabilitation after stroke: an updated systematic review of the literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 27:2306–2318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.05.013

Burns SP, Terblanche M, Perea J et al (2021) mHealth intervention applications for adults living with the effects of stroke: a scoping review. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl 3:100095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arrct.2020.100095

Hwang NK, Park JS, Chang MY (2021) Telehealth interventions to support self-management in stroke survivors: a systematic review. Healthcare. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040472

Bendixen RM, Levy C, Lutz BJ et al (2008) A telerehabilitation model for victims of polytrauma. Rehabil Nurs 33:215–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2008.tb00230.x

Hwang NK, Jung YJ, Park JS (2020) Information and communications technology-based telehealth approach for occupational therapy interventions for cancer survivors: a systematic review. Healthcare. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040355

Verma R, Saldanha C, Ellis U et al (2021) eHealth literacy among older adults living with cancer and their caregivers: a scoping review. J Geriatr Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2021.11.008

Brick R, Padgett L, Jones J et al (2022) The influence of telehealth-based cancer rehabilitation interventions on disability: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01181-4

Schäfer AGM, Zalpour C, von Piekartz H et al (2018) The efficacy of electronic health-supported home exercise interventions for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 20:e152. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9465

Phuphanich ME, Sinha KR, Truong M et al (2021) Telemedicine for musculoskeletal rehabilitation and orthopedic postoperative rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 32:319–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2020.12.004

Perju-Dumbrava L, Barsan M, Leucuta DC et al (2022) Artificial intelligence applications and robotic systems in Parkinson’s disease (review). Exp Ther Med 23:153. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2021.11076

Voth M, Chisholm S, Sollid H et al (2022) Efficacy, effectiveness, and quality of resilience-building mobile health apps for military, veteran, and public safety personnel populations: scoping literature review and app evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 10:e26453. https://doi.org/10.2196/26453

Miranda-Duro MDC, Nieto-Riveiro L, Concheiro-Moscoso P et al (2021) Occupational therapy and the use of technology on older adult fall prevention: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020702

Zak M, Sikorski T, Wasik M et al (2022) Frailty syndrome-fall risk and rehabilitation management aided by virtual reality (VR) technology solutions: a narrative review of the current literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052985

Zonneveld M, Patomella AH, Asaba E et al (2020) The use of information and communication technology in healthcare to improve participation in everyday life: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 42:3416–3423. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1592246

Esfandiari E, Miller WC, Berardi A et al (2022) Telehealth interventions for mobility after lower limb loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prosthet Orthot Int 46:108–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/pxr.0000000000000075

Caouette A, Vincent C, Montreuil B (2007) Use of telemonitoring by elders at home: actual practice and potential. Can J Occup Ther 74:382–392. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.07.004

Liu L, Stroulia E, Nikolaidis I et al (2016) Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 91:44–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.04.007

Choukou MA, Maddahi A, Polyvyana A et al (2021) Digital health technology for indigenous older adults: a scoping review. Int J Med Inform 148:104408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104408

Fong J, Ocampo R, Gross DP et al (2020) Intelligent robotics incorporating machine learning algorithms for improving functional capacity evaluation and occupational rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil 30:362–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09888-w

Law M, Cooper B, Strong S et al (1996) The person-environment-occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther 63:9–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841749606300103

Park S, Fisher AG, Velozo CA (1994) Using the assessment of motor and process skills to compare occupational performance between clinic and home settings. Am J Occup Ther 48:697–709. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.48.8.697

Higgen FL, Heine C, Krawinkel L et al (2020) Crossmodal congruency enhances performance of healthy older adults in visual-tactile pattern matching. Front Aging Neurosci 12:74. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.00074

Hommel B, Kray J, Lindenberger U (2011) Feature integration across the lifespan: stickier stimulus-response bindings in children and older adults. Front Psychol 2:268. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00268

Galvin R, Stokes E, Cusack T (2014) Family-mediated exercises (FAME): an exploration of participant’s involvement in a novel form of exercise delivery after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 21:63–74. https://doi.org/10.1310/tsr2101-63

la Cour K, Ledderer L, Hansen HP (2015) “An arena for sharing”: exploring the joint involvement of patients and their relatives in a cancer rehabilitation intervention study. Cancer Nurs 38:E1-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000149

Øksnebjerg L, Woods B, Ruth K et al (2020) A tablet app supporting self-management for people with dementia: explorative study of adoption and use patterns. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8:e14694. https://doi.org/10.2196/14694

Liu C, Prvu-Bettger J, Sheehan OC et al (2021) Association of formal and informal care with health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms: findings from the caring for adults recovering from the effects of stroke study. Disabil Rehabil 43:1092–1100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1650965

Sclarsky H, Kumar P (2021) Community-based primary care management for an older adult with COVID-19: a case eeport. Am J Occup Ther 75:7511210030p1-7511210030p7. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2021.049220

Hoffmann T, Cantoni N (2008) Occupational therapy services for adult neurological clients in Queensland and therapists’ use of telehealth to provide services. Aust Occup Ther J 55:239–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00693.x

Nyman A, Zingmark M, Lilja M et al (2022) Information and communication technology in home-based rehabilitation—a discussion of possibilities and challenges. Scand J Occup Ther. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2022.2046152

Graessel E, Stemmer R, Eichenseer B et al (2011) Non-pharmacological, multicomponent group therapy in patients with degenerative dementia: a 12-month randomizied, controlled trial. BMC Med 9:129. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-129

Baglio F, Griffanti L, Saibene FL et al (2015) Multistimulation group therapy in Alzheimer’s disease promotes changes in brain functioning. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 29:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968314532833

Toledano-González A, Labajos-Manzanares T, Romero-Ayuso DM (2018) Occupational therapy, self-efficacy, well-being in older adults living in residential care facilities: a randomized clinical trial. Front Psychol 9:1414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01414

Griffin A, Gorman AO, Robinson D et al (2022) The impact of an occupational therapy group cognitive rehabilitation program for people with dementia. Aust Occup Ther J. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12795

Petersen RC, Smith G, Kokmen E et al (1992) Memory function in normal aging. Neurology 42:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.42.2.396

Sanchez M, Schultz-Krohn W, Pham A et al (2016) Roles of occupational therapists in driving rehabilitation programs. Am J Occup Ther 70:7011505118p7011505111-7011505118p7011505111. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2016.70S1-PO2043

American Occupational Therapy Association (2022) Role of Occupational Therapy in Pain Management. Am J Occup Ther. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.75S3001

Ho ECM, Siu AMH (2018) Occupational therapy practice in sleep management: a review of conceptual models and research evidence. Occup Ther Int 2018:8637498. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8637498

Funding

This work was supported by the Geriatric Health Project of Healthcare Commission Foundation of Jiangsu Province [LK2021034] and the Research Planning Project of Higher Medical Education Research Center of Shandong Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD: conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. YY and XW: performed the search and completed data extraction. BX: analyzed the feasibility of the article. LM and YX: were responsible for the overall management and supervision of the article. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This review does not contain any experiments involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

This is a review article, and informed consent was not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J., Yang, Y., Wu, X. et al. The telehealth program of occupational therapy among older people: an up-to-date scoping review. Aging Clin Exp Res 35, 23–40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02291-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02291-w