Abstract

Aim

Home healthcare (HHC) provides continuous care for disabled patients. However, HHC referral after the emergency department (ED) discharge remains unclear. Thus, this study aimed its clarification.

Methods

A computer-assisted HHC referral by interdisciplinary collaboration among emergency physicians, case managers, nurse practitioners, geriatricians, and HHC nurses was built in a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. Patients who had HHC referrals after ED discharge between February 1, 2020 and September 31, 2020, were recruited into the study. A non-ED HHC cohort who had HHC referrals after hospitalization from the ED was also identified. Comparison for clinical characteristics and uses of medical resources was performed between ED HHC and non-ED HHC cohorts.

Results

The model was successfully implemented. In total, 34 patients with ED HHC and 40 patients with non-ED HHC were recruited into the study. The female proportion was 61.8% and 67.5%, and the mean age was 81.5 and 83.7 years in ED HHC and non-ED HHC cohorts, respectively. No significant difference was found in sex, age, underlying comorbidities, and ED diagnoses between the two cohorts. The ED HHC cohort had a lower median total medical expenditure within 3 months (34,030.0 vs. 56,624.0 New Taiwan Dollars, p = 0.021) compared with the non-ED HHC cohort. Compared to the non-ED HHC cohort, the ED HHC cohort had a lower ≤ 1 month ED visit, ≤ 6 months ED visit, and ≤ 3 months hospitalization; however, differences were not significant.

Conclusion

An innovative ED HHC model was successfully implemented. Further studies with more patients are warranted to investigate the impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aging is an important issue in public health worldwide. In the United States, the older population (≥ 65 years) was 16.9% in 2020 and projected to be 19.0% in 2025 [1]. In Taiwan, the older population is 16.2% in 2021 and projected to be 20% in 2025 [2]. In addition to rapid aging, a low birth rate is another important problem, and the effect of both contributed to a decreased population in Taiwan since 2020 [3]. Older adults are unable to seek medical care when necessary due to chronic and complex conditions, decreased family support, and increased disability [4]. Older patients who are disabled have prolonged hospitalization due to insufficient family support, which increased the burden of national health insurance [4]. Therefore, integrated home healthcare (HHC) was initiated in Taiwan in 2015 to provide convenient healthcare and decrease hospitalization stay due to social problems [4].

The emergency department (ED) is at the crossroad of home, hospitalization, ambulatory care, and long-term care facility [5]. Therefore, ED management greatly impacts the outcome of older patients [5]. The American College of Emergency Physicians suggests that ED provides a key opportunity for using less expensive and more convenient outpatient treatments in the older population [5]. HHC is always initiated by discharge planning during the patient’s hospitalization and rarely at the ED. In the hospital-at-home program of the United States, patients are referred from the ED or inpatient hospital beds [6, 7]. The hospital-at-home care model in the United States included nurse and physician home visits, intravenous medications, point-of-care testing, remote monitoring, and video communication [7]. It is more advanced than the HHC model with only nurse and physician home visits and almost oral medications in Taiwan. A HHC model after ED discharge is not yet developed in Taiwan. In addition, the interdisciplinary collaboration between ED staff and HHC providers for patient referral and comparison of outcomes between ED HHC and HHC after hospital discharge remains unclear in the literature. Therefore, this study was conducted for its clarification.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting, and participants

This study was conducted in the Chi Mei Medical Center (CMMC), a tertiary medical center in Southern Taiwan. There were more than 60 full-time attending physicians and residents, serving for > 121,000 patients in the ED in the CMMC in 2019 [8]. The CMMC ED established a Chi Mei Integrated Geriatric Emergency Team in 2016 and the first Geriatric ED in Taiwan in 2019 to lead and improve geriatric care for the rapidly increasing older population [9]. The Geriatric ED of CMMC implemented several studies and strategies to build the local data and solutions for the older population in Taiwan, including emergency medical services in the older population [10], geriatric syndromes and hospice care needs [11], a novel comprehensive screening tool (Emergency Geriatric Assessment) [12], computer-based and pharmacist-assisted medication review [13], and hospice and palliative care [14].

First, an interdisciplinary team was built, including ED staff (emergency physicians, ED case managers [also called transitional care nurses], and ED nurse practitioners) and HHC providers (geriatricians and HHC nurses) for implementing HHC after ED discharge in December 2019 (Fig. 1). Second, two ED case managers (both are registered nurses) received HHC training for 2 months to understand the HHC contents and get a close relationship with HHC providers. Third, a flowchart of computer-assisted referral protocol for ED HHC was built after a consensus of the interdisciplinary team (Fig. 2). All patients in the ED, who fit all the following criteria, were candidates for ED HHC: (1) discharge from ED; (2) living at home (i.e., not a resident of long-term care facility); (3) disability or inconvenience for the hospital visits; and (4) < 30 min-drive between patient’s home and hospital. Fourth, a computer-assisted ED HHC referral was built in the hospital information system (HIS) of ED (Supplementary Fig. 1). Fifth, educational programs using a computer-assisted referral for all the ED staff were initiated and the implementation of ED HHC was announced on January 1, 2020.

Flowchart of computer-assisted referral protocol for ED HHC. *All the four criteria were the candidates for ED HHC: (1) discharge from ED; (2) living at home (i.e., not a resident of long-term care facility); (3) disability or inconvenience for hospital visits; and (4) < 30 min-drive between patient’s home and hospital. ED emergency department, HHC home healthcare, HIS hospital information system

Data collection

Data of patients with a successful referral for ED HHC between February 1, 2020 and September 30, 2020, were retrospectively collected as the study cohort. A comparison cohort (non-ED HHC) was randomly selected from patients who received HHC discharged from the geriatric ward in CMMC between February 1, 2020 and September 30, 2020. The patients in non-ED HHC cohort were also from the ED. Data collection was performed by an experienced ED nurse practitioner who was blind to the outcomes of recruited patients. The study was not affected by COVID-19 because there was no pandemic during the study period in Taiwan.

Outcome measurements

Clinical characteristics, length of stay (LOS) in the index ED visit and hospitalization, expenditures of index ED visit, index hospitalization, and within 3 months after HHC referral and ED visit and hospitalization after HHC referral between two cohorts by the following 6 months were compared. The LOS in the ED is the duration of the stay in the ED. The expenditure was assessed from the patient’s National Health Insurance application.

Ethical statements

This study was conducted after the approval of the institutional review board of the study hospital. All patient data were anonymized. Patient informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and observational nature of the study. The welfare of patients was not affected by the waiver.

Statistics

The Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variable analyses and the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables analyses. Logistic regression analyses were used to compare ED visits and hospitalization after HHC referral between patients in non-ED HHC and ED HHC cohorts. Statistical Analysis System 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The significance level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

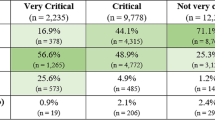

A model of ED HHC was successfully implemented in the CMMC. In total, 34 patients with ED HHC and 40 patients with non-ED HHC were identified in the study for comparison (Table 1). The mean age in the ED HHC and non-ED HHC was 81.5 and 83.7 years, respectively. The proportion of ≥ 85 years in the non-ED HHC cohort was higher than in ED HHC cohorts (50.0% vs. 35.3%); however, the difference among age sub-groups was not significant (p = 0.431). Most patients were triage 2 or 3 and non-traumatic causes in the index ED visits. We used the Taiwan Triage and Acuity Scale [15] for the ED triage, which was modified from the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale [16]. The most common underlying comorbidities in the ED HHC cohort were hypertension (70.6%), followed by diabetes (61.8%), dementia (38.2%), cerebrovascular disease (38.2%), and chronic kidney disease (20.6%). All differences of underlying comorbidities between the two cohorts were not significant. The ED HHC cohort revealed 14.7% of patients with Foley indwelling, 2.9% with nasogastric feeding, 0% with a tracheostomy, 29.4% were bedridden, and 0% received hospice and palliative care. The most common ED diagnosis in the ED HHC cohort was urinary tract infection (50%), followed by fever (20.6%), delirium (8.8%), hyponatremia (5.9%), pneumonia (5.9%), femoral fracture (2.9%), weakness (2.9%), and acute kidney injury (2.9%). All differences in ED diagnoses between the two cohorts were not significant.

The LOSs in the index ED visit were not statistically different between the two cohorts (ED HHC: 28.7 ± 26.0 h vs. non-ED HHC: 25.1 ± 14.9 h, p = 0.476) (Table 2). Compared with the non-ED HHC cohort, the ED HHC cohort had a higher medical expenditure in the index ED visit (4363.6 ± 4074.2 New Taiwan Dollars [NTD] vs. 1179.4 ± 405.1 NTD, p < 0.001). However, the total hospitalization expenditure in the ED HHC cohort was zero since patients were discharged from the ED and received subsequent post-acute care by HHC. Compared with the non-ED HHC cohort, total medical expenditure within 3 months after referral for HHC was significantly lower in the ED HHC cohort (median: 34,030.0 NTD vs. 56,624.0 NTD). The ED visit ≤ 3 days after referral for HHC was 5.9% in the ED HHC cohort and 2.5% in the non-ED HHC cohort (p = 0.591). The numbers of ED visits after referral for HHC in ED HHC cohort were 0.4 ± 0.8 (mean ± standard deviation) within 1 month, 0.8 ± 1.1 within 3 months, and 1.5 ± 2.8 within 6 months. No significant difference was found in the ED visit numbers after HHC referral between the two cohorts. The hospitalization of ≤ 14 days after HHC referral was 5.9% in the ED HHC cohort and 5.0% in the non-ED HHC cohort (p > 0.999). The number of hospitalizations after referral for HHC in the ED HHC cohort was 0.5 ± 0.8 within 3 months and 0.8 ± 1.1 within 6 months. No significant difference was found in the hospitalization number after HHC referral between the two cohorts.

Compared with non-ED HHC, logistic regression showed that the ED HHC cohort had fewer ED visits within 1 month [adjusted odds ratio (OR): 0.1; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0–4.3] and within 6 months (adjusted OR 0.1; 95% CI 0–3.6) after HHC referral; however, the difference was not significant (Table 3). The number of hospitalizations within 3 months was fewer in the ED HHC cohort than in the non-ED cohort (adjusted OR 0.004; 95% CI < 0.001–12.8); however, the difference was not significant.

Discussion

This study showed that ED HHC model implementation is practical with ED staff and HHC provider collaboration. A computer-assisted tool via HIS made the HHC referral more convenient for all ED staff. The total medical expenditure within 3 months after HHC referral was significantly lower in the ED HHC cohort than in the non-ED HHC cohort. The ED HHC cohort showed fewer ED visits within 1 month, ED visits within 6 months, and hospitalizations within 3 months compared to the non-ED HHC cohort; however, logistic regression showed that the differences were not significant. The most common ED diagnosis in the ED HHC cohort was urinary tract infection, followed by fever, delirium, hyponatremia, pneumonia, femoral fracture, weakness, and acute kidney injury.

The ED HHC model fits the gap of care continuity for patients who are disabled and provides convenient post-acute care to help their families [17]. The most common obstacle for the ED HHC is the lack of HHC education of ED staff [17]. In addition, ED staff are prone to make disposition decisions for patients as soon as possible due to the busy and often crowded ED environment. If the ED HHC referral is inconvenient for the ED staff, it will not become an option for their disposition decisions [17]. To minimize the obstacles of HHC referral, dedicated case managers were employed, a computer-assisted referral tool in the HIS was built, and educational programs were provided for all the ED staff in this model. If the ED staff had enough time and HHC knowledge, the referral is directly initiated by the treating physician while the patient remains in the ED (Fig. 2). Contrarily, the referral is initiated by pressing the referral button in the HIS when the ED staff does not have enough time or referral knowledge. After the patient is discharged, a dedicated case manager will contact the patient and families to discuss the possibility of subsequent HHC.

Close collaboration between the ED staff and HHC providers also plays an important role in the ED HHC model success [18]. In addition to building an interdisciplinary team and HHC training of ED case managers, the following efforts were made to achieve close collaboration: (1) emergency physician who oversees the model and case managers join the HHC monthly meetings; (2) geriatrician who provides HHC join the handover meeting in the ED every morning and visit patients observed in the ED; and (3) real-time team communication using communication software (Supplementary Table 1). Computer-assisted tool via HIS made the HHC referral more convenient that increased the will of ED staff referral. A previous study reported that the lack of real-time referral discussion between the case managers and patients and/or families limited the ED HHC referral [19]. The patient in our model was discharged after the initiation of computer-assisted referral and the case manager will contact the patient and/or families for arranging the HHC later, which increases referral success.

In addition to providing a convenient method for post-acute care and subsequent long-term care for patients who are disabled, our ED HHC model showed a lower total medical expenditure within 3 months than patients who received HHC after hospitalization. The finding suggests that the ED HHC model does not only help patients who are not hospitalized but need medical care, but also lower the medical cost, leading to a win–win situation. The ED visit within 1 month, ED visit within 6 months, and hospitalizations within 3 months in the ED HHC cohort were fewer than the non-ED HHC cohort; however, the difference was not significant. The possible explanation is the small sample size. Recruiting more patients for comparison is necessary to clarify this issue.

ED HHC nature is a kind of post-acute care; however, the HHC also becomes chronic care since those receiving HHC have a disability and often multiple chronic comorbidities. Particularly, the ED HHC completes the continuity of patient care, including post-acute care, and bridges chronic care according to patient needs. The HHC in Taiwan is different from the model of hospital-at-home in the United States. The HHC in Taiwan includes patients who need main chronic care. Therefore, their medications are almost all in oral form, different from the intravenous medication in the acute care of hospital-at-home. In other countries, hospital-at-home provides hospital-level care in patient homes as an in-hospital stay substitute [7, 20]. The index diseases in the HHC in Taiwan are less severe than patients receiving hospital-at-home in the United States due to medical care limitations.

The major strength of this study is the successfully implemented first ED HHC model in Taiwan, which has become an important reference for interdisciplinary collaboration between ED and HHC worldwide. The major limitation is the small sample size, which could not reflect the actual difference between ED HHC and non-ED HHC. Further study by recruiting more patients is undergoing in our hospital to clarify this issue. Another limitation is this model may not be generalized to other hospitals or nations due to different medical resource and insurance. Modification of the model may be needed if other hospital wants to adopt this model.

Conclusion

The first ED HHC model was successfully implemented in Taiwan to be an important reference for interdisciplinary collaboration between the ED staff and HHC providers. Educational programs for all the ED staff, close communication with the interdisciplinary team members, and computer-assisted tool via HIS for referral are important factors for the success. Total medical expenditure within 3 months was lower in the ED HHC cohort than in the non-ED HHC cohort, which suggests that patients who fit the HHC criteria may be better to be directly referred from the ED instead of HHC after hospitalization. Medical resource use, including subsequent ED visits and hospitalization after index ED visits, needs more data for future clarification.

Availability of data and material

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Projections by age and sex composition of the population. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/popproj/2017-summary-tables.html. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

National Statistics Bulletin https://www.stat.gov.tw/public/Data/132162358VPAVQ8D.pdf. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

National demographics https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

National Health Insurance Home Medical Integrated Care Pilot Project https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Resource/bulletin/5699_1040004024-2.pdf. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

American College of Emergency P, American Geriatrics S, Emergency Nurses A, Society for Academic Emergency M, Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines Task F (2014) Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 63:e7–25

Summary of New CMS Flexibilities for Acute Hospital Care at Home Program. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/11/summary-new-cms-flexibilities-acute-hospital-care-home-program-bulletin-11-30-20.pdf. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B et al (2020) Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 172:77–85

Introduction of Chi Mei Medical Center. http://www.chimei.org.tw/newindex/assets/img/about/about_chimei/english.pdf. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

Introduction for Geriatric Emergency Department. http://sub.chimei.org.tw/57900/index.php/specially/specially3. Accessed 08 Aug 2021

Huang CC, Chen WL, Hsu CC et al (2016) Elderly and nonelderly use of a dedicated ambulance corps’ emergency medical services in Taiwan. Biomed Res Int 2016:1506436

Ke YT, Peng AC, Shu YM et al (2020) Prevalence of geriatric syndromes and the need for hospice care in older patients of the emergency department: a study in an Asian Medical Center. Emerg Med Int 2020:7174695

Ke YT, Peng AC, Shu YM et al (2018) Emergency geriatric assessment: a novel comprehensive screen tool for geriatric patients in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 36:143–146

Liu YL, Chu LL, Su HC et al (2019) Impact of computer-based and pharmacist-assisted medication review initiated in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 67:2298–2304

Weng TC, Yang YC, Chen PJ et al (2017) Implementing a novel model for hospice and palliative care in the emergency department: an experience from a tertiary medical center in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore) 96:e6943

Ng CJ, Yen ZS, Tsai JC et al (2011) group Tnw: validation of the Taiwan triage and acuity scale: a new computerised five-level triage system. Emerg Med J 28:1026–1031

Bullard MJ, Unger B, Spence J et al (2008) Revisions to the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) adult guidelines. CJEM 10:136–151

Castro JM, Anderson MA, Hanson KS et al (1998) Home care referral after emergency department discharge. J Emerg Nurs 24:127–132

Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B et al (2016) The future of home health care: a strategic framework for optimizing value. Home Health Care Manag Pract 28:262–278

Brookoff D, Minniti-Hill M (1994) Emergency department-based home care. Ann Emerg Med 23:1101–1106

Arsenault-Lapierre G, Henein M, Gaid D et al (2021) Hospital-at-home interventions vs in-hospital stay for patients with chronic disease who present to the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2111568

Acknowledgements

We thank Yi-Chun Lin (case manager and RN), Jui-Chin Hsu (HHC nurse), Yao-Mei Chen (RN), Shiu-Yuan Chung (RN), and all the ED staff and HHC providers for their collaborations and Enago for their English language editing service for this work.

Funding

This study was supported by Grant physician-scientist 11001, Grant CMFHR11066, Grant 110CMKMU-13, and Grant CMFHR11114 from Chi Mei Medical Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLH, KTT, SPH, and CC Huang designed and conceived this study and wrote the manuscript. THT, PCY, CC Hsu, and HJL assisted the implementation and wrote the manuscript. CHH performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration after the approval of the institutional review board of the study hospital. All patient data were anonymized. Patient informed consent was waived due to the retrospective and observational nature of the study. The welfare of patients was not affected by the waiver.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Impact statement

We certify that this work is novel of recent novel clinical research.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hsu, SL., Tsai, KT., Tan, TH. et al. Interdisciplinary collaboration and computer-assisted home healthcare referral in the emergency department: a retrospective cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res 34, 1939–1946 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02109-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02109-9