Abstract

Purpose

Although insecure attachment and interpersonal problems have been acknowledged as risk and maintaining factors of eating disorders (EDs), the mediating role of interpersonal problems between attachment style and ED psychopathology has been poorly explored. The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating role of interpersonal problems between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology.

Methods

One-hundred-nine women with anorexia nervosa and 157 women with bulimia nervosa filled in the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) and the Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) revised scale to assess ED core symptoms and attachment styles, respectively. Interpersonal difficulties were evaluated by the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32). A mediator’s path model was conducted with anxious and avoidant attachment subscores as independent variables, ED core symptoms as dependent variables and interpersonal difficulties as mediators. The diagnosis was entered in the model as a confounding factor.

Results

The socially inhibited/avoidant interpersonal dimension was a mediator between avoidant attachment and the drive to thinness as well as between avoidant attachment and body dissatisfaction. An indirect connection was found between attachment-related anxiety and bulimic symptoms through the mediation of intrusive/needy score.

Conclusions

Social avoidance and intrusiveness mediate the relationships between avoidant and anxious attachment styles and ED psychopathology. These interpersonal problems may represent specific targets for psychotherapeutic treatments in individuals with EDs and insecure attachment.

Level of evidence

Level III: Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case–control analytic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The attachment theory states that an innate predisposed psychobiological system motivates people to seek proximity to significant others in times of distress [1]. Repeated interactions between the infant and attachment figures, who demonstrate to be available, sensitive and responsive to the infant’s needs, will lead the individual to develop an attachment security and build positive mental representations of self and others. In contrast, when caregivers are not available or are unpredictable negative “internal working models” of self and others are built [2, 3]. These cognitive-affective schema of relational expectations, emotions, and behaviour that results from early interactions with attachment figures persist in adulthood and are named attachment styles [4, 5]. Secure attached individuals can deal with a variety of emotions experienced in interpersonal interactions, to communicate and accept their feelings, to seek aid and proximity when feeling overwhelmed, to reflect on their own mental states and on those of the others (i.e., mentalizing abilities) [6, 7]. Insecure attachment includes two main categories: the anxious or preoccupied and the avoidant or dismissive style. A caregiver who facilitates the formation of an anxious attachment in offspring typically exhibits inconsistent and unpredictable reactions, excessive protectiveness and criticism, emotional volatility, anxiety, and emotional reliance on the child. Indeed, attachment anxiety is related to a person who worries that a significant other will not be available and responsive in times of difficulty [8]. On the other hand, a parent who is inclined towards developing an avoidant attachment in offspring typically displays emotional detachment and a lack of responsiveness to the child's requirements, advocates for premature self-reliance, and downplays or overlooks emotional displays. Thereby attachment avoidance is related to a negative view of the others with a trend to self-rely, to maintain behavioural independence and to minimize emotion expression [9]. To address dysfunctional beliefs and emotions arising from insecure attachment styles, attachment-based psychotherapy was developed [10]. This form of psychoanalytic psychotherapy has been effective in the treatment of various psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression [10].

Insecure attachment is a risk factor for eating disorders (EDs) [8, 11, 12]. Indeed, insecure attachment was associated to dysfunctional eating behaviours in the general population [13], and people with EDs showed a higher prevalence of insecure attachment as compared to healthy individuals [14]. A systematic review [15] also quantified the association between insecure attachment and EDs showing a medium to high effect size (r = 0.41; d = 1.31). Attachment insecurity has been associated with the severity of ED-related symptoms and proved to be a transdiagnostic risk factor for EDs [8, 16]. In addition, attachment insecurity has a negative effect on psychotherapy outcomes as shown by heightened dropping out in patients with higher attachment avoidance and worse treatment outcomes in patients with higher attachment anxiety [17, 18].

Several psychological and biological mechanisms have been proposed to explain the association between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology. In their meta-analytic review Cortes-Garcia et al. [19] found that emotion dysregulation and depressive symptoms were the strongest mediators of such a relationship. Neuroticism, perfectionism, problems with mindfulness and social comparison were also observed as mediators but with a low to moderate effect [19]. Subsequent studies suggested further mediators such as lack of confidence towards body feelings and lack of emotional acceptance [20]. This is in line with the four mechanisms proposed by Faber et al. [13] to explain the association between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology in a non-clinical population: a direct and general vulnerability, difficulties with emotions, negative self-esteem, and interpersonal problems. Insecure attached people have poor conflict management and difficulties in sharing intimacy [21] and show loneliness and decreased relationship satisfaction [22, 23]. In individuals with EDs insecure attachment was associated with heightened emotional and biological vulnerability to an acute social challenge [24]. However, the relationship between insecure attachment styles and interpersonal difficulties as well as the mechanisms by which interpersonal difficulties make individuals with insecure attachment more vulnerable towards ED psychopathology have been under investigated. This is an important literature gap also considering the centrality of interpersonal difficulties in the psychopathology of EDs [15, 25]. As a proof of this, patients recalled social difficulties as preceding their ED and worsening after illness onset [26]. Experimental studies have demonstrated heightened sensitivity to social stress [27, 28] and attentional bias towards social rejection [29] in individuals with EDs and interpersonal difficulties have been shown to predict treatment outcome [30].

The aim of this study was to explore which specific interpersonal problems (i.e., submissiveness, assertiveness, hostility, intrusiveness, having difficulties supporting others, being excessively caring or dependent) mediate the relationship between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology. Given that avoidant people are usually cold, introverted, and competitive, while anxious individuals are often overly emotional [31, 32], we hypothesized that hostility and having difficulties supporting others were involved in the association between avoidant attachment and ED psychopathology, while being excessively caring or dependent was mediating between the anxious style and ED psychopathology.

Methods

Participants

A consecutive sample of individuals attending the ED outpatient centre at University of Campania L. Vanvitelli was invited to take part into the study if the following criteria were met: (a) current diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN), atypical AN or bulimia nervosa (BN) according to DSM-5; (b) age ≥ 14 years; (c) absence of comorbid bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or substance-related disorder. All the participants gave their written consent after being thoroughly informed about the nature of the study. Socio-demographic and clinical data were collected through a semi-structured interview conducted by an expert psychiatrist. Diagnosis and comorbidities were assessed at admission to the ED unit by a trained psychiatrist and then confirmed through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders–Research Version [33]. Each participant was asked to fill in self-report questionnaires as part of the centre’s clinical routine before entering treatment program. The study was approved by University of Campania L. Vanvitelli ethical committee (protocol number 09.32-20210013912).

Clinical questionnaires

-

ED-related symptoms and psychopathology were measured through the Eating Disorders Inventory-2 (EDI-2) [34, 35], which is a self-administered questionnaire encompassing 11 subscales: impulsivity, fear, body dissatisfaction, social insecurity, asceticism, perfectionism, interpersonal distrust, ineffectiveness, drive to thinness, interoceptive awareness, bulimia, and maturity. The scores of core ED symptoms (namely, bulimia (Cronbach’s α = 0.87), body dissatisfaction (Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and drive to thinness (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) subscales) were included in the analyses.

-

The Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR) revised scale is a self-reported questionnaire evaluating the attachment styles [36, 37], in a romantic relationship, which represents an indirect measure of early interactions with caregivers [38]. The ECR provides two main subscales measuring the anxious insecure attachment (Cronbach’s α = 0.82) and the avoidant insecure attachment (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

-

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems 32-item version (IIP-32) [39] was employed to assess interpersonal functioning. This questionnaire explores interpersonal difficulties [39], which are conceptualized in terms of dominance and affiliation. These interpersonal features are divided into eight sub-scales: Overly Accommodating/Exploitable (Cronbach’s α = 0.73), Vindictive/ Self-centred (Cronbach’s α = 0.72), Intrusive/Needy (Cronbach’s α = 0.81), Socially Inhibited/Avoidant (Cronbach’s α = 0.83), Non-assertive (Cronbach’s α = 0.80), Cold/ Distant (Cronbach’s α = 0.75), Self-sacrificing/Overly nurturant (Cronbach’s α = 0.77), and Domineering/Controlling (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Statistical analyses

The normality of data was tested through the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since most of the data were not normally distributed, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare clinical differences between the AN group and the BN group. The Bonferroni correction was applied so that the level of significance was set at p < 0.0026. Mediation analyses were conducted by using JASP software [40]. A multiple mediator’s path model was run with attachment subscores as independent variables, ED core symptoms as dependent variables and interpersonal difficulties as mediators. The diagnosis was entered in the model as a confounding factor. The statistical significances of the mediating and indirect effects were assessed using bootstrapped procedure (namely, running percentile-based confidence interval of 5000 bootstrap) [41] and the maximum likelihood (ML) method [42].

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants’ mean age was 25.4 years (SD = 9.4, min = 14, max = 54). One-hundred-nine women with AN and 157 women with BN were recruited. Fifty-three (19.9%) patients reported a current diagnosis of an anxiety disorder, thirty-six (13.5%) reported a diagnosis of major depression. As seen in Table 1, differences between AN and BN emerged in terms of age, BMI, years of education, illness duration, and EDI-2 subscale for Bulimia (all p < 0.001). No significant differences emerged between individuals with AN and those with BN regarding insecure attachment styles and interpersonal issues except for intrusive/needy score (p = 0.007) and self-sacrifing/overly nurture score (p = 0.023) which did not persist after Bonferroni correction.

Mediation analysis

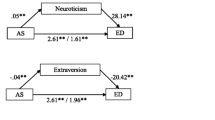

Figure 1 shows the mediation model. A significant direct path between avoidant attachment, drive to thinness (b = 0.19, 95% CI = 0.04–0.34, p = 0.007) and body dissatisfaction (b = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.061–0.326, p = 0.004) emerged, displaying that higher attachment avoidance score was related to heightened drive to thinness and body dissatisfaction. Socially Inhibited/Avoidant score mediated both the associations between avoidant attachment and drive to thinness (b = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.036–0.204, p = 0.008) and between avoidant attachment and body dissatisfaction (b = 0.08, 95% CI = 0.027–0.172, p = 0.012). A significant indirect association emerged between attachment-related anxiety and bulimic symptoms through Intrusive/Needy score (b = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.01–0.04, p = 0.026). Intrusive/Needy also slightly mediated the association between anxious attachment and drive to thinness (b = 0.06, 95% CI = 0.004–0.142, p = 0.086). The diagnosis had a significant effect on Intrusive/Needy pointing that BN diagnosis may account for the indirect effect of attachment-related anxiety on bulimia through Intrusive/Needy score.

Path mediation model showing the association between insecure attachment, interpersonal problems and specific eating symptoms in women with eating disorders. Dotted lines represent significant direct effects, continuous lines represent significant indirect effects. The standardized coefficients are shown in the figure

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the mediation role of interpersonal difficulties between insecure attachment and eating-related core symptoms in a sample with AN and BN. Social inhibition/avoidance mediated the association of avoidant attachment with drive to thinness and body dissatisfaction, while intrusiveness mediated between anxious attachment and bulimic symptoms.

No difference has been observed in the present sample among individuals diagnosed with AN and BN in relation to ED psychopathology, insecure attachment style, and interpersonal difficulties. This is consistent with previous literature: although the relationship between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology has been widely acknowledged [8, 17], no clear association between ED diagnoses and insecure attachment dimensions has been previously detected [8, 17]. Likewise, avoidance of expressing feelings to others giving priority to other people’s feeling over their own and interpersonal distrust and conflict with others were described as the interpersonal difficulties differentiating individuals with AN and those with BN [43], while a few studies have assessed interpersonal difficulties in terms of dominance and affiliation and failed to identify differences between AN and BN [44, 45].

We hypothesized that hostility and being cold were involved in the association between avoidant attachment and ED psychopathology, while being excessively dependent was mediating between the anxious style and ED psychopathology. The present findings align with our hypotheses given that social avoidance is a component of the “cold” dimension and has been described as highly associated with the cold/distant subscore [45, 46], while intrusiveness is included in the “dependent” dimension [39]. Individuals with avoidant attachment styles use to distance themselves from forming close connections, thereby safeguarding themselves from potential rejection [31, 47]. Conversely, individuals with anxious attachment styles are characterized by difficulties respecting personal space and seeking excessive reassurance or attention from others. Therefore, these findings align with attachment theory [31], indicating that avoidance of social interactions may make individuals with avoidant attachment style more vulnerable to body dissatisfaction and drive to thinness, while the need of avoiding rejection to foster intimacy, even at the expense of respecting others’ personal space and autonomy, may promote bulimic symptoms in those with higher anxious attachment styles. The latter finding may be suggested above all in individuals with BN given the significant effect of BN diagnosis on intrusive/needy score observed in the mediation model. Considering literature on the association between interpersonal difficulties and ED psychopathology [43, 48], the suggested role of social exposure avoidance has been supported in individuals with EDs and avoidant attachment, while intrusiveness has emerged as an under-detected interpersonal problem with relevance in individuals with EDs and anxious attachment. In addition, it is possible to suggest that eating-related symptoms may represent dysfunctional strategies to cope with the highlighted interpersonal difficulties encountered by individuals with insecure attachment. Eating symptoms may allow patients to divert their attention from their undesired feelings in the context of social exposure or perception of abandonment. The current findings corroborate a wide body of research outlining that an insecure attachment style fosters ED symptomatology [8, 31]. However, previous studies have gathered evidence about the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties [19, 20] and self-esteem [13]. Although interpersonal difficulties were hypothesized to mediate this association [11, 13], social comparison and behavioural inhibition related to sensitivity to punishment have been the only investigated interpersonal dimensions so far [49, 50]. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to investigate the mediating role of interpersonal problems, measured by the IIP-32 questionnaire, between insecure attachment and ED symptoms.

Previous research has consistently shown a significant association between high insecure attachment and more severe ED symptoms, as well as unfavourable treatment outcomes, across all subtypes of EDs [51, 52]. In addition, improvements in attachment anxiety and avoidance have been associated with reduced interpersonal difficulties [53]. Therefore, these findings underscore the importance of interventions aimed at improving attachment functioning to mitigate the severity of ED symptoms. In this line, evidence-based psychotherapies (i.e., the Focal Psychodynamic Therapy [54]) targeting attachment-related issues may be suggested for individuals with EDs and high insecure attachment [55]. Furthermore, specific interpersonal problems such as social avoidance and lack of interpersonal boundary emerged in this study as mediating between insecure attachment and ED symptoms. Therefore, interventions proved to ameliorate interpersonal problems in EDs may be suggested to address these interpersonal difficulties considering their relationships with attachment experiences. In this line, social inhibition can be effectively addressed using cognitive-behavioral therapy, which reduces social anxiety and improves social functioning by targeting negative thought patterns and avoidance behaviours [56]. For those exhibiting high levels of intrusiveness, interpersonal psychotherapy may be particularly effective, as it improves communication skills and management of interpersonal disputes, thereby mitigating the effects of intrusiveness in relationships [57].

Concluding, attachment styles and their relationships with difficulty approaching others and imposing one’s needs with difficulty respecting the personal boundaries of other people may represent more tailored treatment targets in individuals with EDs and high avoidant and anxious attachment dimensions, respectively.

Strength and limits

The main strength of the study is that it is the first to examine interpersonal styles in terms of dominance and affiliation as mediators of the relationship between insecure attachment and ED psychopathology. Limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. First, a cross-sectional approach was employed and precluded to draw causality. A further consequence of this issue is that, although the ECR questionnaire is considered a reliable indicator of infant attachment experiences [27], its scores may reflect the cognitive-affective schema employed in current peer relationships rather than a trait. Second, the use of self-report questionnaires may induce bias in the reported findings, although there is large agreement in considering self-report attachment instruments appropriate [41]. Third, the inclusion of participants into a unique sample prevents assessing differences between ED diagnoses. However, literature data do not support specific associations between ED diagnoses and attachment insecure styles [13] and the diagnosis factor was considering in the model suggesting a higher relevance of the anxious attachment pathway in individuals with BN. Fourth, the lack of a matched healthy control sample does not allow to verify if the identified mediation effects specifically characterize individuals with EDs.

What is already known on this subject?

Insecure attachment style fosters ED symptomatology and previous studies have gathered evidence about the mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties and self-esteem. Although interpersonal difficulties were hypothesized to mediate this association, social comparison and behavioural inhibition related to sensitivity to punishment have been the only investigated interpersonal dimensions so far. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first attempt to investigate the mediating role of interpersonal problems, measured by the IIP-32 questionnaire, between insecure attachment and ED symptoms.

What this study adds?

Our findings suggest that interpersonal problems, namely social avoidance and intrusiveness, mediate the relationship between avoidant and anxious attachment styles and ED psychopathology, emphasizing the importance of addressing specific interpersonal difficulties in psychotherapeutic interventions for individuals with EDs and insecure attachment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss, Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). Basic Books

Bowlby J (1973) Attachment and loss, Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books

Andresen JB, Graugaard C, Andersson M, Bahnsen MK, Frisch M (2022) Adverse childhood experiences and mental health problems in a nationally representative study of heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual Danes. World Psychiatry 21(3):427–435. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21008

Hazan C, Shaver P (1987) Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol 52(3):511–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.3.511

Ainsworth M, Blehar M, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum ed.; 1978.

Fuendeling JM (1998) Affect regulation as a stylistic process within adult attachment. J Soc Pers Relat 15(3):291–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407598153001

Mallinckrodt B (2010) Attachment, social competencies, social support, and interpersonal process in psychotherapy. Psychother Res 10(3):239–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/10.3.239

Monteleone AM (2023) Families in eating disorders: an attachment perspective. In: Robinson P, Wade T, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Fernandez-Aranda F, Treasure J, Wonderlich S (eds) Eating disorders. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97416-9_80-1

Mikulincer M (1998) Attachment working models and the sense of trust: an exploration of interaction goals and affect regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol 74(5):1209–1224. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1209

Schwartz J, Pollard J (2004) Introduction to the special issue: attachment-based psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Attach Hum Dev 6(2):113–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730410001695358

Tasca GA (2019) Attachment and eating disorders: a research update. Curr Opin Psychol 25:59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.03.003

Morris AS, Hays-Grudo J (2023) Protective and compensatory childhood experiences and their impact on adult mental health. World Psychiatry 22(1):150–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21042

Faber A, Dubé L, Knäuper B (2018) Attachment and eating: a meta-analytic review of the relevance of attachment for unhealthy and healthy eating behaviors in the general population. Appetite 123:410–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.043

Zachrisson HD, Skårderud F (2010) Feelings of insecurity: review of attachment and eating disorders. Eat Disord Rev 18(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.999

Caglar-Nazali HP, Corfield F, Cardi V, Ambwani S, Leppanen J, Olabintan O et al (2014) A systematic review and meta-analysis of ‘Systems for Social Processes’ in eating disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42:55–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.12.002

Watson D, Levin-Aspenson HF, Waszczuk MA, Conway CC, Dalgleish T, Dretsch MN, Eaton NR, Forbes MK, Forbush KT, Hobbs KA, Michelini G, Nelson BD, Sellbom M, Slade T, South SC, Sunderland M, Waldman I, Witthöft M, Wright AGC, Kotov R, HiTOP Utility Workgroup et al (2022) Validity and utility of Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): III. Emotional dysfunction superspectrum. World Psychiatry 21(1):26–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20943

Tasca GA, Balfour L (2014) Attachment and eating disorders: a review of current research. Int J Eat Disord 47(7):710–717. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22302

Wampold BE, Flückiger C (2023) The alliance in mental health care: conceptualization, evidence and clinical applications. World Psychiatry 22(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21035

Cortés-García L, Takkouche B, Seoane G, Senra C (2019) Mediators linking insecure attachment to eating symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213099

Cascino G, Ceres R, Donato S, Barone E, Tretola L, Del Vecchio A et al (2023) Emotional non-acceptance mediates the relationship between insecure attachment and specific psychopathology in women with eating disorders. Eat Disord Rev 31(5):608–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2982

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2007) The attachment behavioral system basic. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (eds) Attachment in adulthood: structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press

Larose S, Bernier A (2001) Social support processes: mediators of attachment state of mind and adjustment in late adolescence. Attach Hum Dev J 3(1):96–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730010024762

Nesse RM (2023) Evolutionary psychiatry: foundations, progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 22(2):177–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21072

Monteleone AM, Ruzzi V, Pellegrino F, Patriciello G, Cascino G, Del Giorno C, Monteleone P, Maj M (2019) The vulnerability to interpersonal stress in eating disorders: the role of insecure attachment in the emotional and cortisol responses to the trier social stress test. Psychoneuroendocrinology 101:278–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.12.232

Monteleone AM, Cascino G (2021) A systematic review of network analysis studies in eating disorders: Is time to broaden the core psychopathology to non specific symptoms. Eur Eat Disord Rev 29(4):531–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2834

Cardi V, Mallorqui-Bague N, Albano G, Monteleone AM, Fernandez-Aranda F, Treasure J (2018) Social difficulties as risk and maintaining factors in anorexia nervosa: a mixed-method investigation. Front Psychiatry 26(9):12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00012

Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Ruzzi V, Pellegrino F, Carfagno M, Raia M, Del Giorno C, Monteleone P, Maj M (2020) Multiple levels assessment of the RDoC “system for social process” in Eating Disorders: biological, emotional and cognitive responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. J Psychiatr Res 130:160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.039

Meneguzzo P, Meregalli V, Collantoni E, Cardi V, Tenconi E, Favaro A (2023) Virtual rejection and overinclusion in eating disorders: an experimental investigation of the impact on emotions, stress perception, and food attitudes. Nutrients 15(4):1021. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15041021

Monteleone AM, Treasure J, Kan C, Cardi V (2018) Reactivity to interpersonal stress in patients with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using an experimental paradigm. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 87:133–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.002

Oldershaw A, Lavender T, Schmidt U (2018) Are socio-emotional and neurocognitive functioning predictors of therapeutic outcomes for adults with anorexia nervosa? Eur Eat Disord Rev 26(4):346–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2602

Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM (1991) Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J Pers Soc Psychol 61:226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

McGorry PD, Mei C, Chanen A, Hodges C, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey E (2022) Designing and scaling up integrated youth mental health care. World Psychiatry 21(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20938

First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL (2016) User’s guide for the SCID-5-CV Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® disorders: Clinical version. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc

Garner DM (1991) Eating disorder Inventory-2; professional manual. Psychological assessment resources

Garner DM, Rizzardi M., Trombini E., Trombini G (1995) EDI 2: Eating disorder Inventory-2; manuale. Organizzazioni speciali; 1995. Garner DM, Rizzardi M., Trombini E., Trombini G. EDI 2: Eating disorder Inventory-2; manuale. Organizzazioni speciali

Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA (2000) An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol 78(2):350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350

Calvo V (2008) Italian version of the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, &Brennan, 2000) questionnaire. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.16974.54082

Sibley CG, Liu JH (2004) Short-term temporal stability and factor structure of the revised experiences in close relationships (ECR-R) measure of adult attachment. Personality Individ Differ 36(4):969–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00165-X

Horowitz LM, Alden LE, Wiggins JS, Pincus AL (2000) Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32/IIP-64). Psychological Corporation, London

Van Doorn J, van den Bergh D, Böhm U, Dablander F, Derks K, Draws T et al (2021) The JASP guidelines for conducting and reporting a Bayesian analysis. Psychon Bull Rev 28(3):813–826. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-020-01798-5

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

MacKinnon DP (2011) Integrating mediators and moderators in research design. Res Soc Work Pract 21(6):675–681. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731511414148

Arcelus J, Haslam M, Farrow C, Meyer C (2013) The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: a systematic review and testable model. Clin Psychol Rev 33(1):156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.009

Ward A, Ramsay R, Turnbull S, Benedettini M, Treasure J (2000) Attachment patterns in eating disorders: past in the present. Int J Eat Disord 28(4):370–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4%3c370::aid-eat4%3e3.0.co;2-p

Lo Coco G, Mannino G, Salerno L, Oieni V, Di Fratello C, Profita G, Gullo S (2018) The Italian Version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP-32): Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure in Clinical and Non-clinical Groups. Front psychol 9:341. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00341

Salazar J, Martí V, Soriano S, Beltran M, Adam A (2010) Validity of the Spanish version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems and its use for screening personality disorders in clinical practice. J Pers Disord 24(4):499–515. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.499

Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2012) An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 11(1):11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.003

Cardi V, Tchanturia K, Treasure J (2018) Premorbid and illness-related social difficulties in eating disorders: an overview of the literature and treatment developments. Curr Neuropharmacol 16(8):1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180118100028

De Paoli T, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Halliwell E, Puccio F, Krug I (2017) Social rank and rejection sensitivity as mediators of the relationship between insecure attachment and disordered eating. Eat Disord Rev 25(6):469–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2537

Monteleone AM, Cardi V, Volpe U, Fico G, Ruzzi V, Pellegrino F et al (2018) Attachment and motivational systems: relevance of sensitivity to punishment for eating disorder psychopathology. Psychiatry Res 260:353–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.002

Illing V, Tasca GA, Balfour L, Bissada H (2010) Attachment insecurity predicts eating disorder symptoms and treatment outcomes in a clinical sample of women. J Nerv Ment Dis 198(9):653–659. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ef34b2

Leichsenring F, Steinert C, Rabung S, Ioannidis JPA (2022) The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: an umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry 21(1):133–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20941

Maxwell H, Tasca GA, Ritchie K, Balfour L, Bissada H (2014) Change in attachment insecurity is related to improved outcomes 1-year post group therapy in women with binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy (Chic) 51(1):57–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031100

Zipfel S, Wild B, Groß G, Friederich HC, Teufel M, Schellberg D et al (2014) Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 383(9912):127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61746-8

Gratz KL, Tull MT (2022) A clinically useful conceptualization of emotion regulation grounded in functional contextualism and evolutionary theory. World Psychiatry 21(3):460–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21021

Hickin N, Käll A, Shafran R, Sutcliffe S, Manzotti G, Langan D (2021) The effectiveness of psychological interventions for loneliness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 88:102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102066

Hinrichsen GA (2001) Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res 10(4):282

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The authors declare that no Funds, Grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and AM.M. contributed to the study conception and design. Data curation was performed by G.C, M.C. and E.B. Formal analysis was performed by G.C. and M.C. Investigation was conducted by E.A., A.V., L.Ma. and R.B. AM.M. and G.C. contributed to methodology. Supervision was performed by AM.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.C. and AM.M. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University of Campania L. Vanvitelli ethical committee, approval number [09.32–20210013912].

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carfagno, M., Barone, E., Arsenio, E. et al. Mediation role of interpersonal problems between insecure attachment and eating disorder psychopathology. Eat Weight Disord 29, 43 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01673-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-024-01673-5